Abstract

The lack of disease-modifying treatments for Parkinson’s disease (PD) is in part due to an incomplete understanding of the disease’s etiology. Alpha-synuclein (α-syn) has become a point of focus in PD due to its connection to both familial and idiopathic cases—specifically its localization to Lewy bodies (LBs), a pathological hallmark of PD. Within this review, we will present a comprehensive overview of the data linking synuclein-associated Lewy pathology with intracellular dysfunction. We first present the alterations in neuronal proteins and transcriptome associated with LBs in postmortem human PD tissue. We next compare these findings to those associated with LB-like inclusions initiated by in vitro exposure to α-syn preformed fibrils (PFFs) and highlight the profound and relatively unique reduction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in this model. Finally, we discuss the multitude of ways in which BDNF offers the potential to exert disease-modifying effects on the basal ganglia. What remains unknown is the potential for BDNF to mitigate inclusion-associated dysfunction within the context of synucleinopathy. Collectively, this review reiterates the merit of using the PFF model as a tool to understand the physiological changes associated with LBs, while highlighting the neuroprotective potential of harnessing endogenous BDNF.

Subject terms: Parkinson's disease, Cell biology

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects over a million Americans and results in nearly $25 billion per year in health care costs as well as immeasurable personal costs to patients and families. It is now appreciated that PD is a complex, multifaceted disorder that impacts both the central and peripheral nervous systems with patients experiencing symptoms ranging from motor dysfunction to constipation to dementia; all contributing to a significant detriment in quality of life. However, the cardinal motor symptoms of tremor, rigidity, akinesia/bradykinesia and postural instability first described by James Parkinson in 1817 are still requisite for diagnosis and are the primary target for therapeutic intervention1. PD motor symptoms are caused by the loss of dopaminergic transmission in the striatum due to progressive loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and their projections to the caudate and putamen. As a result, current pharmacotherapies attempt to augment nigrostriatal dopamine transmission. Unfortunately, these approaches are not disease-modifying, with pharmacotherapy ultimately losing therapeutic efficacy and causing troublesome side effects as the disease progresses.

The lack of disease-modifying treatments for PD is partly due to an incomplete understanding of the disease’s etiology. PD belongs to a family of disorders termed synucleinopathies, which are characterized pathologically by the deposition of the protein alpha-synuclein (α-syn) into neuronal inclusions termed Lewy bodies (LBs). Despite the identification of genetic forms of PD (reviewed in ref. 2), the molecular etiology underlying disease origin and progression remain unknown. Nevertheless, abnormal α-syn proteostasis is a common factor between both sporadic and familial forms of PD (reviewed in ref. 3). Together with the loss of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons, accumulation of α-syn into LBs is the pathological hallmark of PD. There are many ideas surrounding the mechanism by which aberrant α-syn proteostasis may contribute to PD (reviewed in ref. 4); however, each is contested, and none have been proven outright. Further, whether LBs themselves directly cause toxicity or are merely a cellular marker associated with pathogenic processes has yet to be determined. In either case, understanding the pathogenic mechanisms associated with, or induced by, LB formation is critical to the development of disease-modifying treatments.

α-synuclein

α-syn is a small (14 kDa) protein encoded by the SNCA gene. It is abundantly expressed in the nervous system5 and exists in a natively unfolded state under normal physiological conditions, though its conformation changes depending on its environment6 and interactions with binding partners7. For example, α-syn has a strong affinity for high curvature lipid membranes (i.e. vesicles), and it changes conformation from two alpha helices7 to one alpha helix upon interacting with them8–10. Functionally, α-syn is enriched in synaptic terminals where it is known to play critical roles in neurotransmission3,5,11. It is thought to mediate trafficking, docking, and endocytosis of synaptic vesicles via interactions with soluble NSF attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex proteins11,12 and synaptic vesicles directly13. Of relevance to nigrostriatal neurons, α-syn is involved in dopamine synthesis14,15, handling16,17, and release11,18,19, and is posited to serve as a negative regulator of synaptic transmission3.

α-syn remains an ‘intrinsically disordered’ protein due to its dynamic nature with no clear tertiary structure, making it particularly vulnerable to aggregation6,20. Many conditions can promote this transition from soluble, functional α-syn into insoluble fibrils (reviewed in3), and once this process begins, it proceeds in a feed-forward manner in which oligomers form and become fibrils which seed and recruit soluble α-syn into more fibrils, a process that once escalated is largely irreversible21. While α-syn oligomers and aggregates have not been proven to be directly toxic, they are consistently associated with toxicity (reviewed in refs. 22,23). Within PD and other synucleinopathies, α-syn transforms from a soluble, functional protein to a phosphorylated, aggregated, protein (i.e., LBs) that becomes associated with pathogenic consequences24.

Insights derived from postmortem PD tissue

Three different technical approaches that provide insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms associated with LBs have been employed in studies examining PD pathogenesis in human postmortem tissue (Table 1). First, quantitative immunofluorescent techniques have been used to examine proteins within LB-containing vs. non-LB-containing neurons. These studies have demonstrated that LB-containing neurons exhibit reduced ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and lysosomal markers25, kinesis motor proteins, and pro-survival myocyte enhancer factor 2D26,27, and increased DNA strand breaks28 and toll-like receptor 229. Whereas this immunofluorescence approach maintains the specificity of the LB vs. no LB comparison, it is limited by the number of different proteins that can be analyzed at any one time.

Table 1.

Synucleinopathy-associated pathogenesis in postmortem PD tissue.

| Authors | Year | Comparator | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUANTITATIVE IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE | |||

| Chu et al.25 | 2009 | LB vs non-LB neurons | Decreased ubiquitin-proteasome system and lysosomal markers with LBs |

| Chu et al.26 | 2011 | LB vs non-LB neurons | Decreased myocyte enhancer factor 2D with LBs |

| Chu et al.27 | 2012 | LB vs non-LB neurons |

Decreased kinesis motor proteins in neurons with LBs Increased expression of dynein in neurons with LBs |

| Dzamko et al.29 | 2017 | LB vs non-LB neurons | Increased toll-like receptor 2 in neurons with LBs |

| Schaser et al.28 | 2019 | LB vs non-LB neurons | Increased DNA double stranded breaks in neurons with LBs |

| WHOLE TISSUE MICROARRAY | |||

| Grunblatt et al.30 | 2004 | PD SN vs control SN |

68 downregulated in PD involved in signal transduction, protein degradation, dopamine handling, ion transport, and energy pathways. 69 upregulated in PD involved in protein modification, metabolism, transcription, and inflammation. |

| Hauser et al.31 | 2005 | PD SN vs control SN | 96 genes differentially expressed. Main pathways were chaperones, ubiquitination, vesicle trafficking, and mitochondrial function |

| Duke et al.32 | 2006 | PD SN vs control SN | Downregulation of pathways related to ubiquitin-proteasome system and mitochondrial function. |

| Elstner et al.33 | 2009 | PD SN vs control SN | 4 genes differentially expressed. Pathways were mitochondrial function, dopamine metabolism, axon guidance, and vesicle transport. |

| Botta-Orfila et al.34 | 2012 | PD LC vs control LC | Differential expression of genes related to synaptic transmission, neuron projection, and immune system related pathways |

| Dijkstra et al.35 | 2015 |

PD SN vs ILBD SN vs control SN |

Dysregulation of pathways related to axonal guidance, endocytosis and immune response (ILBD) as well as dysregulated mTOR and EIF2 signaling in both ILBD and PD. |

| LASER CAPTURE MICRODISSECTION | |||

| Lu et al.36 | 2005 |

PD SN neurons with LBs vs PD SN neurons without LBs |

Increased USP8 (pro-UPS function) Increased ANP32B (proapoptic) Decreased KLHL1 and BPAG1 (cytoskeleton organization), Decreased Stch (encodes HSP 70) |

| Cantuti-Castelvetri et al.37 | 2007 |

PD SN neurons vs control SN neurons Both male and female |

Females: Alterations in genes with protein kinase activity, genes involved in proteolysis and WNT signaling pathway. Males: Alterations in protein-binding proteins and copper-binding proteins. |

| Elstner et al.38 | 2011 |

PD SN neurons vs control SN neurons |

Downregulation of genes coding for mitochondrial and ubiquitin-proteasome system proteins |

| Grundemann et al.145 | 2011 |

PD SN neurons vs control SN neurons |

Increased SNCA expression |

| Lin et al.39 | 2012 |

ILBD SN neurons vs PD SN neurons vs control SN neurons |

Increased mitochondrial DNA mutations in early PD/ILBD group compared to late stage and controls |

| Grunewald et al.40 | 2016 |

PD SN neurons vs control SN neurons |

Reduced respiratory chain complex I and II |

| Su et al.42 | 2017 |

PD SN neurons vs control SN neurons |

Decreased SNCA expression, no changes in Nurr1, RET, PARK7, SLC18A2, BDNF, DDC, TH, MEF2D or PITX3 |

| Duda et al.41 | 2018 |

PD SN neurons vs control SN neurons |

Dysregulation in genes encoding for ion channels, dopamine metabolism proteins, and PARK. |

LB Lewy body, PD Parkinson’s disease, SN substantia nigra, LC locus coeruleus, ILBD incidental Lewy body disease.

In contrast to the immunofluorescence approach, several studies have used the approach of microarray profiling (Table 1) to compare whole nigral tissue from varying stages of PD to control brains, identifying a wide array of dysregulated genes involved in synaptic transmission, protein degradation, dopamine handling, ion transport, transcription, inflammation, vesicle trafficking, axon guidance and mitochondrial function30–35. The whole tissue microarray approach has the advantage of an unbiased survey of gene expression changes, but at the cost of losing the specificity necessary to precisely identify the transcriptome of neurons possessing LBs. This is due to the fact that LB and non-LB-containing neurons (and other cell types) are present within the whole tissue punch. Further, depending on disease stage, the whole tissue approach can be confounded by the loss of nigral neurons themselves.

The approach of laser capture microdissection (LCM) combined with gene expression analysis has been used to compare dopaminergic nigral neurons in PD vs control brains, allowing for single neuron resolution to be combined with either focused or unbiased expression analysis (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, only one LCM study has specifically compared expression differences between LB-containing and non-LB-containing nigral neurons36. This focused study, conducted in a small sample size, suggested that LB-containing nigral neurons have increased expression of proapoptotic and pro-UPS genes, and decreased expression of genes associated with cytoskeletal organization and molecular chaperones. The remainder of LCM studies have examined transcript differences between nigral dopamine neurons in disease and healthy control nigral dopamine neurons, without using the presence of LBs as a determining selection factor. These studies show that nigral dopamine neurons from PD brains have alterations in genes associated with protein kinase activity, UPS functioning, mitochondrial function, dopamine metabolism, and ion channels37–41. Less agreement has surfaced from LCM studies with regards to the expression of α-syn itself, with earlier studies suggesting increased SNCA expression in PD nigral neurons [80], and a more recent analysis suggesting no change in SNCA expression or trophic factor signaling and dopamine metabolism genes [81].

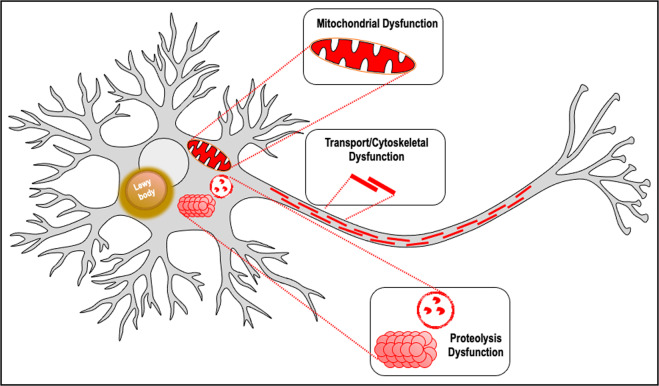

In order to understand what pathogenic mechanisms are consistently associated with LBs, it is reasonable to look for consensus across different methodological approaches with an emphasis on LB-specific analyses (Fig. 1). Both immunofluorescence and LCM of LB-containing nigral neurons reveal alterations in proteolysis markers25,36 as well as alterations in transport/cytoskeleton organization27,36. Some whole SN tissue analysis and LCM studies of nigral dopamine neurons also have detected proteolysis and transport/cytoskeletal dysfunction30–32,37,38. Mitochondrial dysfunction is quite frequently detected by both whole SN tissue analysis and LCM approaches30–32,38–40,42; however, the association specifically with LBs has not directly been established. Despite these efforts using PD brain tissue, the pivotal pathogenic mechanisms associated with the formation of LBs have yet to be revealed. The heterogeneity of PD combined with the difficulty of gleaning mechanistic insight using analysis of static postmortem tissue further confound the potential for our understanding of LB-associated pathogenesis. Fortunately, an alternative approach is providing new information of the dynamic cellular alterations associated with the formation of α-syn inclusions.

Fig. 1. Pathogenic mechanisms consistently associated with Lewy bodies across multiple approaches.

Both immunofluorescence and LCM of LB-containing nigral neurons reveal alterations in proteolysis markers25,36 as well as alterations in transport/cytoskeleton organization27,36. Some whole SN tissue analysis and LCM studies of nigral DA neurons also have detected proteolysis and transport/cytoskeletal dysfunction30–32,37,38. Mitochondrial dysfunction is quite frequently detected by both whole SN tissue analysis and LCM approaches30–32,38,39,145 however the association specifically with LBs has not directly been established.

Insights from the α-syn PFF model

Since the earliest observation of LBs, the question of what role this intracellular structure plays in degeneration remains unanswered. LBs may trigger cytotoxic events, be beneficial, or may simply represent an artifact that is inconsequential to either pathogenesis or neuroprotection. Transgenic animal models in which α-syn aggregates are formed rarely lead to overt degeneration43–46, limiting their utility for understanding the relationship between α-syn aggregation and degeneration. However, a relatively recent model described in wildtype mice47 demonstrated the ability of intrastriatal injection of preformed α-syn fibrils (PFFs) to seed LB-like aggregates in the SN and multiple cortical regions. PFFs are taken up into neurons48 and once inside initiate a conversion of normal α-syn into phosphorylated and misfolded α-syn, ultimately accumulating to form LB-like aggregates48,49. Importantly, a definitive link between PFF-seeded pathological α-syn aggregation and eventual neuronal death has been established in this model50.

Although multiple studies have examined the degenerative phenotype induced by PFF injections to mice and rats47,51–53, studies using PFFs in primary neuronal cultures prove particularly useful in revealing the intracellular events observed in tandem with the formation and maturation of PFF-triggered LB-like inclusions. Neurons in which phosphorylated α-syn inclusions form following α-syn PFF exposure exhibit multiple structural, protein, and transcriptomic changes that are associated with pathophysiological processes and, in the case of longer in vitro intervals, cell death (Table 2). Specifically, PFF-initiated α-syn inclusions result in decreased expression of synaptic proteins48,54,55, impairments in axonal transport49, and mitochondrial impairment54,56,57. Structurally and functionally, α-syn inclusion-bearing neurons display impaired excitability and decreased spine density48,58,59. Notably, results from the in vitro PFF model reveal heavy overlap with results from LB-containing neurons from PD brains, particularly with regard to transport/cytoskeleton disorganization and mitochondrial dysfunction. The most comprehensive study to date in cultured neurons with PFF-seeded α-syn inclusions was conducted by Mahul-Mellier and colleagues55 and examined longitudinal transcriptomic alterations in neurons as α-syn inclusions matured. In addition to observing the decreased expression of synaptic genes, cytoskeletal organization genes, and mitochondrial genes, this study also revealed decreased expression of a gene that has previously received little attention with regard to α-syn inclusion-associated alterations: brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Specifically, out of the 11767 total mouse genes that were examined, only 0.05% were significantly decreased across all time points, including bdnf. In inclusion-bearing neurons, bdnf decreased 1.2 fold at day 7, 2.32 fold at day 14, and 2.5 fold at day 21. Further, of all the genes significantly decreased at day 21, the magnitude of bdnf decrease was greater than 98% of all the others. In other words, only 9 other genes (out of 11767 total, 562 were downregulated) exhibited a greater magnitude of reduction than bdnf at day 21. The 9 other downregulated genes included genes encoding proteins with functions related to protein coding and processing (Spink8, Fam150b, Pcsk1), transcription (Npas4), G protein signaling (Rgs4), adhesion (Bves), lipoprotein metabolism (Lipg), vesicle trafficking (Sv2b), and the gene for the tachykinin receptor 3 (Tacr3).

Table 2.

Synucleinopathy-associated pathogenesis in PFF culture studies.

| Authors | Year | Comparator | Findings | Culture Age | PFF Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volpicelli-Daley et al.48 | 2011 | Hippocampal neurons with and without α-syn aggregates |

Decreased expression of multiple synaptic proteins. Impairments in neuronal excitability and connectivity. |

E16-E18 mouse | Mouse |

| Volpicelli-Daley et al.49 | 2014 | Hippocampal neurons with and without α-syn aggregates | Impairment of axonal transport of RAB7 and TrkB- containing endosomes and autophagosomes. Accumulation of pERK5. | E16-E18 mouse | Mouse |

| Tapias et al.54 | 2017 | Mesencephalic dopamine neurons with and without α-syn aggregates |

Decreased expression of synaptic proteins. Alterations in axonal transport-related proteins. Impaired mitochondria. Increased oxidative stress. |

E17 rat | Human |

| Froula et al.58 | 2018 | Hippocampal neurons with and without α-syn aggregates |

Decreased mushroom spine density. Increased excitatory postsynaptic currents. Increased presynaptic docked vesicles. Decreased frequency and amplitude of spontaneous calcium transients. |

E16-E18 mouse | Mouse |

| Grassi et al.56 | 2018 | Hippocampal neurons with and without α-syn aggregates | pSyn* induces mitochondrial toxicity and fission, energetic stress and mitophagy. | E16-E18 mouse | Mouse |

| Wu et al.59 | 2019 | Hippocampal neurons with and without α-syn aggregates |

Decreased excitatory postsynaptic current frequency. Altered dendritic spines. |

E16-E18 mouse | Human |

| Wang et al.57 | 2019 | Cortical neurons with and without α-syn aggregates | Deficits in mitochondrial respiration | P1 mouse and rat | Mouse |

| Mahul-Mellier et al.55 | 2020 | Hippocampal neurons with and without α-syn aggregates |

Transcriptomic changes over time: D7: 75 total genes (27 upregulated, 48 downregulated) encoding for proteins located within synapses, axons, or secretory and exocytic vesicles. Genes encoding for proteins involved in neurogenesis and the organization, growth, and the extension of the axons and dendrites D14: 329 total genes (106 upregulated, 223 downregulated) linked to the synaptic, neuritic, and vesicular cellular compartments. Genes associated with neurogenesis, calcium homeostasis, synaptic homeostasis, cytoskeleton organization, response to stress, and neuronal cell death process. D21: 1017 total genes (455 upregulated, 562 downregulated) with enrichment in genes encoding for proteins related to the ion channel complex, plasma membrane protein complex, cell–cell junctions, synaptic functions, response to oxidative stress and mitochondria. D14 vs. D21: Differential expression of genes associated with mitochondrial and synaptic functions. |

P0 mouse | Mouse |

D day in vitro. Culture age animal age animals at the time of primary neurons harvest.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

The best-studied neurotrophic factors in the context of PD are glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neurturin (NTN), BDNF, cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor (CDNF), and mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor (MANF)60. The potential for trophic factors to protect nigrostriatal neurons in PD has been extensively explored in recent years, with the GDNF family ligands, GDNF and NTN, advancing to clinical trials that have all ultimately failed to provide significant clinical improvement in PD subjects61–66. To date, clinical research efforts investigating the neuroprotective potential of trophic factors in PD have been mainly directed toward GDNF and NTN. As a result, the neuroprotective potential of other trophic factors has been explored only sparingly. Of these, BDNF is a member of the mammalian neurotrophin family and is abundantly expressed in the central nervous system from development through adulthood, where it plays critical roles in neuronal survival, migration, axonal and dendritic outgrowth, synaptogenesis, synaptic transmission, and synaptic plasticity67–72. BDNF also promotes neuroprotection after injury by inhibiting pro-apoptotic molecules73.

Examination of BDNF mRNA and protein levels in PD subjects has revealed alterations relative to aged matched controls. Postmortem examination suggests that BDNF mRNA and protein are downregulated in the SNpc of patients with PD74–76. This decrease in nigral BDNF mRNA correlates with both decreased soma size and neuron survival, suggesting that individual nigral neurons with low BDNF levels may be particularly vulnerable to degeneration74.

The biological activity of BDNF is tightly regulated by its gene expression, axonal transport, and release. It is well-known that BDNF is synthesized and released in an activity-dependent manner and as such, endogenous extracellular BDNF levels are extremely low72. BDNF release is dependent on stimulus pattern, with high-frequency bursts being the most effective77. The bdnf gene has nine promoters that produce 24 different transcripts, all of which are translated into a single, identical, mature dimeric protein78. This allows for tight, activity-dependent regulation whereby specific exon-containing transcripts are differentially regulated by specific neuronal activities including physical exercise, seizures, antidepressant treatment, and regular neuronal activation79–85. Neuronal activity also regulates the transport of BDNF mRNA into dendrites allowing for locally translated BDNF to modulate synaptic transmission and synaptogenesis86–88.

BDNF protein is initially synthesized as a precursor protein (preproBDNF) in the endoplasmic reticulum. Following cleavage of the signal peptide into a 32-kDa proBDNF protein, it is either cleaved intracellularly into mature BDNF (mBDNF) or transported to the Golgi for sorting into either constitutive or regulated secretory vesicles for release (reviewed in ref. 89). Mature BDNF is the prominent isoform in the adult, whereas proBDNF is highly expressed at early postnatal stages90. proBDNF was initially thought to be an inactive, intracellular precursor for mBDNF in the adult, but it is now understood to be a secreted, biologically active molecule with pro-apoptotic effects90–94. While proBDNF regulation and secretion are still relatively unclear processes, both proBDNF and mBDNF are packaged into vesicles of the activity-regulated secretory pathway with the secretion of proBDNF more prominent than mBDNF91.

BDNF protein is found widespread throughout the CNS both pre- and postsynaptically and affects neuronal survival, growth/arborization, and synaptic plasticity95. It undergoes both retrograde and anterograde transport96,97; therefore the site of BDNF synthesis and function are not always the same. For example, BDNF protein is abundant in the striatum where it is critical for normal function. However, there is relatively little BDNF mRNA in the striatum98. Instead, the overwhelming majority of striatal BDNF is anterogradely transported from the cortex and to a lesser extent from the SNpc97,99. BDNF release is triggered in an activity-regulated, Ca2+-dependent manner. This can occur by presynaptic influx of Ca2+100, postsynaptic influx of Ca2+,101, or from release of intracellular Ca2+ stores102.

BDNF binds and activates two known surface receptors: mBDNF binds to tropomyosin related-kinase receptor B (TrkB) whereas proBDNF binds to pan neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR; p75)103. TrkB is part of the tyrosine kinase family of receptors, along with TrkA and TrkC. BDNF binds to TrkB with high affinity inducing a pro-survival cascade. In contrast, all neurotrophins bind to p75 with low affinity (also known as low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor, LNGFR) inducing apoptosis, and the balance of p75 and the Trk receptors ultimately determines cell survival or death (reviewed in104). The majority of BDNF signaling is attributed to mBDNF binding and activating TrkB. However, evidence suggests that proBDNF binds p75, and pro- and mBDNF elicit opposing synaptic effects through activation of their respective receptors90–93,105. Moreover, mBDNF also binds a truncated TrkB receptor lacking the tyrosine kinase domain involved in downstream signaling106,107. Thus, when bound to p75 or truncated TrkB, BDNF is functionally inhibited from activating the canonical BDNF-TrkB signaling pathway, acting as a dominant-negative regulatory mechanism108.

BDNF-TrkB signaling can activate two distinct postsynaptic signaling pathways: the canonical and the noncanonical pathways. In the canonical pathway, three signaling cascades have been identified: (1) the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal related-kinase (MAPK/ERK) cascade, (2) the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT (PI3K/AKT) cascade, and (3) the phospholipase C gamma (PLCγ) cascade109,110. MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT cascades mediate translation and trafficking of proteins95, whereas PLCγ mediates transcription via intracellular Ca2+ regulation and cyclic adenosine monophosphate and protein kinase activation109. Collectively, these cascades affect neuronal survival, growth/ arborization, and synaptic plasticity95. In the noncanonical pathway, intracellular PI3K-Akt signaling results in phosphorylation of the NMDA receptor 2B subunit,111–113, resulting in potentiated responses. BDNF noncanonical signaling has also been suggested to have effects on presynaptic dopamine release and reuptake114. These immediate phosphorylation events in the noncanonical pathway occur at a much faster rate than the translational and transcriptional events in the canonical pathway. Thus, BDNF can exert a multitude of effects on the basal ganglia over various time spans.

Can BDNF counteract synucleinopathy-associated pathogenesis?

α-syn inclusions seeded by PFFs are associated with an early and profound decrease in BDNF mRNA in cultured neurons55. Similarly, BDNF mRNA and protein are downregulated in the SNpc of patients with PD74,75. This decrease in nigral BDNF mRNA correlates with both decreased soma size and neuron survival, suggesting that individual nigral neurons with low BDNF levels may be particularly vulnerable to degeneration74. Similarly, BDNF serum levels are lower in early-stage PD patients compared to controls, whereas in later stages BDNF serum levels correlate positively with duration and disease severity115, possibly reflecting a compensatory mechanism. Targeted α-syn overexpression negatively impacts BDNF gene and protein expression, as well as downstream BDNF signaling116–118. Conversely, α-syn silencing results in an upregulation of BDNF mRNA117. Retrograde transport of BDNF is also impaired in neurons that overexpress α-syn118. Neurons with PFF-seeded α-syn inclusions have reduced retrograde transport of the BDNF receptor, TrkB49, and overexpression of α-syn has also been shown to inhibit BDNF-TrkB signaling in vitro119. Collectively, these studies suggest that pathological α-syn decreases levels of BDNF, interferes with retrograde BDNF transport, and decreases TrkB levels and BDNF-TrkB signaling. It is therefore possible that increased BDNF expression could counteract the pathological consequences of synucleinopathy.

Indeed, BDNF has been linked to positive effects on many of the same cellular processes impacted with LBs (Fig. 1). Specifically, BDNF increases mitochondrial oxidative efficiency and combats mitochondrial dysfunction73,120, enhances synaptic transmission121, and promotes synaptic plasticity122 including increasing dendritic spine density123. Further, BDNF improves presynaptic dopamine release and reuptake114 and can protect nigral dopamine neurons from neurotoxicant insult in mesencephalic dopamine neuron cultures and rodent and non-human primate models124,125. Beyond synucleinopathy, impaired BDNF signaling has been documented in other neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease126,127. PD is a heterogeneous disorder with co-pathologies that can include amyloid, which may also be impacted by BDNF. In summary, BDNF-TrkB signaling has the potential to exert a multitude of disease-modifying effects on the basal ganglia and other nuclei.

The earliest studies examining whether increased BDNF levels can be neuroprotective reported positive effects in toxicant models of PD124,125,128–130. What remains unknown is whether therapeutic strategies that increase BDNF or TrkB signaling can exert neuroprotective effects within the context of synucleinopathy. In the α-syn A53T mutant mouse model, the FDA-approved drug, Gilenya (FTY720/fingolimod) decreased α-syn aggregation in the enteric nervous system and alleviated gut motility symptoms in a BDNF-TrkB dependent manner131. Specifically, the use of TrkB antagonist (ANA-12) in young A53T transgenic mice exacerbated constipation and increased synucleinopathy in the gut, both of which were mitigated by Gilenya treatment. Some investigations have explored exercise as a less invasive way to stimulate BDNF-TrkB, as exercise is known to increase BDNF production132. This approach has proven promising in several preclinical animal models of PD in which exercise-induced BDNF upregulation and significantly reduced α-syn aggregation were observed, with no change to soluble α-syn133–136. Another approach to increase endogenous production and release of BDNF is through high-frequency stimulation101,137. We have previously demonstrated that subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS) specifically elevates BDNF mRNA and protein throughout the basal ganglia138–142. Moreover, TrkB blockade prevented the neuroprotection normally associated with stimulation143. STN DBS increases striatal BDNF despite the presence of PFF-seeded α-syn inclusions, which partially restored the normal corticostriatal BDNF relationship144. Collectively, these data present a compelling argument for the potential of DBS-enhanced BDNF to mitigate nigrostriatal terminal dysfunction. Future studies will be required to determine whether DBS-mediated effects on BDNF translate into neuroprotection from α-syn inclusion-associated degeneration.

Conclusion

Investigations using postmortem PD tissue and PFF-exposed cells have revealed multiple pathogenic processes associated with the presence of misfolded pathological α-syn inclusions. Further research is required to determine whether the insight gleaned from understanding LB-associated pathogenesis can be translated into therapies for disease modification in PD.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Support for the preparation of this manuscript came from NS099416 (CES), NS110321 (K.M.M.), and the Pearl Aldrich Research Endowment.

Author contributions

This manuscript was conceived and organized by K.M.M. and C.E.S. The manuscript was first written by K.M.M. and C.E.S., with additional contributions and edits from N.M.M.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41531-021-00179-6.

References

- 1.Marsili L, Rizzo G, Colosimo C. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease: from James Parkinson to the concept of prodromal disease. Front Neurol. 2018;9:156. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lunati A, Lesage S, Brice A. The genetic landscape of Parkinson’s disease. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 2018;174:628–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benskey MJ, Perez RG, Manfredsson FP. The contribution of alpha synuclein to neuronal survival and function—implications for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2016;137:331–359. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obeso JA, et al. Past, present, and future of Parkinson’s disease: a special essay on the 200th anniversary of the shaking palsy. Mov. Disord. 2017;32:1264–1310. doi: 10.1002/mds.27115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwai A, et al. The precursor protein of non-A beta component of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron. 1995;14:467–475. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90302-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinreb PH, Zhen W, Poon AW, Conway KA, Lansbury PT., Jr NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13709–13715. doi: 10.1021/bi961799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra S, Chen X, Rizo J, Jahn R, Sudhof TC. A broken alpha-helix in folded alpha-Synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15313–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson WS, Jonas A, Clayton DF, George JM. Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9443–9449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bussell R, Jr, Eliezer D. A structural and functional role for 11-mer repeats in alpha-synuclein and other exchangeable lipid binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;329:763–778. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jao CC, Der-Sarkissian A, Chen J, Langen R. Structure of membrane-bound alpha-synuclein studied by site-directed spin labeling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8331–8336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400553101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vargas KJ, et al. Synucleins regulate the kinetics of synaptic vesicle endocytosis. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:9364–9376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4787-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burre J, et al. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science. 2010;329:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclein: a neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:2804–2815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02804.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez RG, et al. A role for alpha-synuclein in the regulation of dopamine biosynthesis. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:3090–3099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03090.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez RG, Hastings TG. Could a loss of alpha-synuclein function put dopaminergic neurons at risk? J. Neurochem. 2004;89:1318–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wersinger C, Prou D, Vernier P, Sidhu A. Modulation of dopamine transporter function by alpha-synuclein is altered by impairment of cell adhesion and by induction of oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2003;17:2151–2153. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0152fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fountaine TM, Wade-Martins R. RNA interference-mediated knockdown of alpha-synuclein protects human dopaminergic neuroblastoma cells from MPP(+) toxicity and reduces dopamine transport. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:351–363. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abeliovich A, et al. Mice lacking alpha-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron. 2000;25:239–252. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabin DE, et al. Synaptic vesicle depletion correlates with attenuated synaptic responses to prolonged repetitive stimulation in mice lacking alpha-synuclein. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:8797–8807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08797.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breydo L, Wu JW, Uversky VN. Α-synuclein misfolding and Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1822:261–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood SJ, et al. alpha-synuclein fibrillogenesis is nucleation-dependent. Implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19509–19512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caughey B, Lansbury PT. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;26:267–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bengoa-Vergniory N, Roberts RF, Wade-Martins R, Alegre-Abarrategui J. Alpha-synuclein oligomers: a new hope. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:819–838. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1755-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braak H, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu Y, Dodiya H, Aebischer P, Olanow CW, Kordower JH. Alterations in lysosomal and proteasomal markers in Parkinson’s disease: relationship to alpha-synuclein inclusions. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009;35:385–398. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu Y, Mickiewicz AL, Kordower JH. alpha-synuclein aggregation reduces nigral myocyte enhancer factor-2D in idiopathic and experimental Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;41:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu Y, et al. Alterations in axonal transport motor proteins in sporadic and experimental Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2012;135:2058–2073. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaser AJ, et al. Alpha-synuclein is a DNA binding protein that modulates DNA repair with implications for Lewy body disorders. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10919. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47227-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dzamko N, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 is increased in neurons in Parkinson’s disease brain and may contribute to alpha-synuclein pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:303–319. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1648-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grunblatt E, et al. Gene expression profiling of parkinsonian substantia nigra pars compacta; alterations in ubiquitin-proteasome, heat shock protein, iron and oxidative stress regulated proteins, cell adhesion/cellular matrix and vesicle trafficking genes. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2004;111:1543–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser MA, et al. Expression profiling of substantia nigra in Parkinson disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:917–921. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duke DC, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals link between proteasomal and mitochondrial pathways in Parkinson’s disease. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s10048-006-0033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elstner M, et al. Single-cell expression profiling of dopaminergic neurons combined with association analysis identifies pyridoxal kinase as Parkinson’s disease gene. Ann. Neurol. 2009;66:792–798. doi: 10.1002/ana.21780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Botta-Orfila T, et al. Microarray expression analysis in idiopathic and LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012;45:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dijkstra AA, et al. Evidence for immune response, axonal dysfunction and reduced endocytosis in the substantia nigra in early stage Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0128651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu L, et al. Gene expression profiling of Lewy body-bearing neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2005;195:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantuti-Castelvetri I, et al. Effects of gender on nigral gene expression and Parkinson disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;26:606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elstner M, et al. Neuromelanin, neurotransmitter status and brainstem location determine the differential vulnerability of catecholaminergic neurons to mitochondrial DNA deletions. Mol. Brain. 2011;4:43. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin MT, et al. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in early Parkinson and incidental Lewy body disease. Ann. Neurol. 2012;71:850–854. doi: 10.1002/ana.23568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grunewald A, et al. Mitochondrial DNA depletion in respiratory chain-deficient Parkinson disease neurons. Ann. Neurol. 2016;79:366–378. doi: 10.1002/ana.24571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duda J, Fauler M, Grundemann J, Liss B. Cell-specific RNA quantification in human SN DA neurons from heterogeneous post-mortem midbrain samples by UV-laser microdissection and RT-qPCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1723:335–360. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7558-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su X, et al. Alpha-synuclein mRNA is not increased in sporadic PD and alpha-synuclein accumulation does not block GDNF signaling in Parkinson’s disease and disease models. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:2231–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuoka Y, et al. Lack of nigral pathology in transgenic mice expressing human alpha-synuclein driven by the tyrosine hydroxylase promoter. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001;8:535–539. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahle PJ, et al. Hyperphosphorylation and insolubility of alpha-synuclein in transgenic mouse oligodendrocytes. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:583–588. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rockenstein E, et al. Differential neuropathological alterations in transgenic mice expressing alpha-synuclein from the platelet-derived growth factor and Thy-1 promoters. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;68:568–578. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernagut PO, Chesselet MF. Alpha-synuclein and transgenic mouse models. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004;17:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luk KC, et al. Pathological alpha-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science. 2012;338:949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1227157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volpicelli-Daley LA, et al. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils induce Lewy body pathology leading to synaptic dysfunction and neuron death. Neuron. 2011;72:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Volpicelli-Daley LA, Luk KC, Lee VM. Addition of exogenous alpha-synuclein preformed fibrils to primary neuronal cultures to seed recruitment of endogenous alpha-synuclein to Lewy body and Lewy neurite-like aggregates. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:2135–2146. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osterberg VR, et al. Progressive aggregation of alpha-synuclein and selective degeneration of lewy inclusion-bearing neurons in a mouse model of parkinsonism. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1252–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paumier KL, et al. Intrastriatal injection of pre-formed mouse alpha-synuclein fibrils into rats triggers alpha-synuclein pathology and bilateral nigrostriatal degeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015;82:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duffy MF, et al. Lewy body-like alpha-synuclein inclusions trigger reactive microgliosis prior to nigral degeneration. J. Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:129. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1171-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patterson JR, et al. Time course and magnitude of alpha-synuclein inclusion formation and nigrostriatal degeneration in the rat model of synucleinopathy triggered by intrastriatal alpha-synuclein preformed fibrils. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019;130:104525. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tapias V, et al. Synthetic alpha-synuclein fibrils cause mitochondrial impairment and selective dopamine neurodegeneration in part via iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017;74:2851–2874. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2541-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahul-Mellier AL, et al. The process of Lewy body formation, rather than simply alpha-synuclein fibrillization, is one of the major drivers of neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:4971–4982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913904117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grassi D, et al. Identification of a highly neurotoxic alpha-synuclein species inducing mitochondrial damage and mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E2634–E2643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713849115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X, et al. Pathogenic alpha-synuclein aggregates preferentially bind to mitochondria and affect cellular respiration. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019;7:41. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0696-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Froula JM, et al. alpha-Synuclein fibril-induced paradoxical structural and functional defects in hippocampal neurons. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018;6:35. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0537-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu Q, et al. alpha-synuclein (alphaSyn) preformed fibrils induce endogenous alphaSyn aggregation, compromise synaptic activity and enhance synapse loss in cultured excitatory hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:5080–5094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0060-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chmielarz P, Saarma M. Neurotrophic factors for disease-modifying treatments of Parkinson’s disease: gaps between basic science and clinical studies. Pharm. Rep. 2020;72:1195–1217. doi: 10.1007/s43440-020-00120-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lang AE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intraputamenal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor infusion in Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:459–466. doi: 10.1002/ana.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whone A, et al. Randomized trial of intermittent intraputamenal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2019;142:512–525. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Warren Olanow C, et al. Gene delivery of neurturin to putamen and substantia nigra in Parkinson disease: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Neurol. 2015;78:248–257. doi: 10.1002/ana.24436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bartus RT, et al. Post-mortem assessment of the short and long-term effects of the trophic factor neurturin in patients with α-synucleinopathies. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015;78:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marks WJ, et al. Gene delivery of AAV2-neurturin for Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1164–1172. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paul G, Sullivan AM. Trophic factors for Parkinson’s disease: Where are we and where do we go from here? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019;49:440–452. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hofer MM, Barde YA. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents neuronal death in vivo. Nature. 1988;331:261–262. doi: 10.1038/331261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalcheim C, Gendreau M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor stimulates survival and neuronal differentiation in cultured avian neural crest. Brain Res. 1988;469:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barde YA. The nerve growth factor family. Prog. Growth Factor Res. 1990;2:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(90)90021-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Snider WD, Johnson EM. Neurotrophic molecules. Ann. Neurol. 1989;26:489–506. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kowiański P, et al. BDNF: a key factor with multipotent impact on brain signaling and synaptic plasticity. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;38:579–593. doi: 10.1007/s10571-017-0510-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barde YA, Edgar D, Thoenen H. Purification of a new neurotrophic factor from mammalian brain. EMBO J. 1982;1:549–553. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen, S. D., Wu, C. L., Hwang, W. C. & Yang, D. I. More Insight into BDNF against neurodegeneration: anti-apoptosis, anti-oxidation, and suppression of autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.18, 10.3390/ijms18030545 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Howells DW, et al. Reduced BDNF mRNA expression in the Parkinson’s disease substantia nigra. Exp. Neurol. 2000;166:127–135. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mogi M, et al. Brain-derived growth factor and nerve growth factor concentrations are decreased in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;270:45–48. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Imamura K, et al. Cytokine production of activated microglia and decrease in neurotrophic factors of neurons in the hippocampus of Lewy body disease brains. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0919-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Balkowiec A, Katz DM. Activity-dependent release of endogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor from primary sensory neurons detected by ELISA in situ. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7417–7423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07417.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martínez-Levy GA, Cruz-Fuentes CS. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the central nervous system. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2014;87:173–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tao X, West AE, Chen WG, Corfas G, Greenberg ME. A calcium-responsive transcription factor, CaRF, that regulates neuronal activity-dependent expression of BDNF. Neuron. 2002;33:383–395. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00561-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aid T, Kazantseva A, Piirsoo M, Palm K, Timmusk T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:525–535. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karpova NN. Role of BDNF epigenetics in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76 Pt C:709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pruunsild P, Sepp M, Orav E, Koppel I, Timmusk T. Identification of cis-elements and transcription factors regulating neuronal activity-dependent transcription of human BDNF gene. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:3295–3308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Björkholm C, Monteggia LM. BDNF—a key transducer of antidepressant effects. Neuropharmacology. 2016;102:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gomez-Pinilla F, Zhuang Y, Feng J, Ying Z, Fan G. Exercise impacts brain-derived neurotrophic factor plasticity by engaging mechanisms of epigenetic regulation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011;33:383–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tsankova NM, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Histone modifications at gene promoter regions in rat hippocampus after acute and chronic electroconvulsive seizures. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5603–5610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0589-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tongiorgi E, Righi M, Cattaneo A. Activity-dependent dendritic targeting of BDNF and TrkB mRNAs in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:9492–9505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09492.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tongiorgi E. Activity-dependent expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in dendrites: facts and open questions. Neurosci. Res. 2008;61:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tongiorgi E, Baj G. Functions and mechanisms of BDNF mRNA trafficking. Novartis Found. Symp. 2008;289:136–147. doi: 10.1002/9780470751251.ch11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lessmann V, Gottmann K, Malcangio M. Neurotrophin secretion: current facts and future prospects. Prog. Neurobiol. 2003;69:341–374. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang J, et al. Neuronal release of proBDNF. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:113–115. doi: 10.1038/nn.2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mowla SJ, et al. Biosynthesis and post-translational processing of the precursor to brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12660–12666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Teng HK, et al. ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5455–5463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pang PT, et al. Cleavage of proBDNF by tPA/plasmin is essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity. Science. 2004;306:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.1100135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sasi M, Vignoli B, Canossa M, Blum R. Neurobiology of local and intercellular BDNF signaling. Pflug. Arch. 2017;469:593–610. doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-1964-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cobb MH. MAP kinase pathways. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1999;71:479–500. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(98)00056-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wetmore C, Cao YH, Pettersson RF, Olson L. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: subcellular compartmentalization and interneuronal transfer as visualized with anti-peptide antibodies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:9843–9847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Conner JM, Lauterborn JC, Yan Q, Gall CM, Varon S. Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: evidence for anterograde axonal transport. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2295–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02295.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hofer M, Pagliusi SR, Hohn A, Leibrock J, Barde YA. Regional distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the adult mouse brain. EMBO J. 1990;9:2459–2464. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Altar CA, et al. Anterograde transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its role in the brain. Nature. 1997;389:856–860. doi: 10.1038/39885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Balkowiec A, Katz DM. Cellular mechanisms regulating activity-dependent release of native brain-derived neurotrophic factor from hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10399–10407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10399.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hartmann M, Heumann R, Lessmann V. Synaptic secretion of BDNF after high-frequency stimulation of glutamatergic synapses. EMBO J. 2001;20:5887–5897. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Griesbeck O, et al. Are there differences between the secretion characteristics of NGF and BDNF? Implications for the modulatory role of neurotrophins in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1999;45:262–275. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990515/01)45:4/5<262::AID-JEMT10>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Patapoutian A, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: mediators of neurotrophin action. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2001;11:272–280. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chao MV, Bothwell M. Neurotrophins: to cleave or not to cleave. Neuron. 2002;33:9–12. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00573-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hempstead BL. Deciphering proneurotrophin actions. Handb. Exp. Pharm. 2014;220:17–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45106-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Middlemas DS, Lindberg RA, Hunter T. trkB, a neural receptor protein-tyrosine kinase: evidence for a full-length and two truncated receptors. Mol. Cell Biol. 1991;11:143–153. doi: 10.1128/MCB.11.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Klein R, Conway D, Parada LF, Barbacid M. The trkB tyrosine protein kinase gene codes for a second neurogenic receptor that lacks the catalytic kinase domain. Cell. 1990;61:647–656. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90476-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Haapasalo A, et al. Regulation of TRKB surface expression by brain-derived neurotrophic factor and truncated TRKB isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:43160–43167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yoshii A, Constantine-Paton M. Postsynaptic BDNF-TrkB signaling in synapse maturation, plasticity, and disease. Dev. Neurobiol. 2010;70:304–322. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yoshii A, Constantine-Paton M. Postsynaptic localization of PSD-95 is regulated by all three pathways downstream of TrkB signaling. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2014;6:6. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2014.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen W, et al. BDNF released during neuropathic pain potentiates NMDA receptors in primary afferent terminals. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014;39:1439–1454. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nakai T, et al. Girdin phosphorylation is crucial for synaptic plasticity and memory: a potential role in the interaction of BDNF/TrkB/Akt signaling with NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:14995–15008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2228-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li J, et al. Experimental colitis modulates the functional properties of NMDA receptors in dorsal root ganglia neurons. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G219–G228. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00097.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bosse KE, et al. Aberrant striatal dopamine transmitter dynamics in brain-derived neurotrophic factor-deficient mice. J. Neurochem. 2012;120:385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Scalzo P, Kümmer A, Bretas TL, Cardoso F, Teixeira AL. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor correlate with motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2010;257:540–545. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yuan Y, et al. Overexpression of alpha-synuclein down-regulates BDNF expression. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2010;30:939–946. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9523-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang YC, et al. Knockdown of α-synuclein in cerebral cortex improves neural behavior associated with apoptotic inhibition and neurotrophin expression in spinal cord transected rats. Apoptosis. 2016;21:404–420. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fang F, et al. Synuclein impairs trafficking and signaling of BDNF in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3868. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04232-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kang SS, et al. TrkB neurotrophic activities are blocked by α-synuclein, triggering dopaminergic cell death in Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:10773–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713969114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Markham A, Cameron I, Franklin P, Spedding M. BDNF increases rat brain mitochondrial respiratory coupling at complex I, but not complex II. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:1189–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Su B, Ji YS, Sun XL, Liu XH, Chen ZY. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-induced mitochondrial motility arrest and presynaptic docking contribute to BDNF-enhanced synaptic transmission. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:1213–1226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.526129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Leal G, Comprido D, Duarte CB. BDNF-induced local protein synthesis and synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76 Pt C:639–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.von Bohlen Und Halbach O, von Bohlen Und Halbach V. BDNF effects on dendritic spine morphology and hippocampal function. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;373:729–741. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tsukahara T, Takeda M, Shimohama S, Ohara O, Hashimoto N. Effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced parkinsonism in monkeys. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:733–739. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199510000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yoshimoto Y, et al. Astrocytes retrovirally transduced with BDNF elicit behavioral improvement in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 1995;691:25–36. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00596-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Burbach GJ, et al. Induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in plaque-associated glial cells of aged APP23 transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2421–2430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5599-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tanila H. The role of BDNF in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017;97:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Spina MB, Hyman C, Squinto S, Lindsay RM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects dopaminergic cells from 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;648:348–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Frim DM, et al. Implanted fibroblasts genetically engineered to produce brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevent 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity to dopaminergic neurons in the rat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:5104–5108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Spina MB, Squinto SP, Miller J, Lindsay RM, Hyman C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects dopamine neurons against 6-hydroxydopamine and N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion toxicity: involvement of the glutathione system. J. Neurochem. 1992;59:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vidal-Martínez G, et al. FTY720/fingolimod reduces synucleinopathy and improves gut motility in A53T mice: contributions of pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (PRO-BDNF) and mature BDNF. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:20811–20821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.744029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Palasz, E. et al. BDNF as a promising therapeutic agent in Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 10.3390/ijms21031170 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 133.Zhou W, Barkow JC, Freed CR. Running wheel exercise reduces α-synuclein aggregation and improves motor and cognitive function in a transgenic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0190160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Almeida MF, et al. Effects of mild running on substantia nigra during early neurodegeneration. J. Sports Sci. 2018;36:1363–1370. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2017.1378494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hsueh, S. C. et al. Voluntary physical exercise improves subsequent motor and cognitive impairments in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.19, 10.3390/ijms19020508 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 136.Tuon T, et al. Physical training exerts neuroprotective effects in the regulation of neurochemical factors in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2012;227:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nagappan G, et al. Control of extracellular cleavage of ProBDNF by high frequency neuronal activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1267–1272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807322106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Spieles-Engemann AL, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation increases brain derived neurotrophic factor in the nigrostriatal system and primary motor cortex. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;1:123–136. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2011-11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhang X, Andren PE, Svenningsson P. Repeated l-DOPA treatment increases c-fos and BDNF mRNAs in the subthalamic nucleus in the 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2006;1095:207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Seroogy KB, Gall CM. Expression of neurotrophins by midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Exp. Neurol. 1993;124:119–128. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sauer H, Wong V, Björklund A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-4/5 modify neurotransmitter-related gene expression in the 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1995;65:927–933. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00019-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Friedman WJ, Olson L, Persson H. Cells that express brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the developing postnatal rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1991;3:688–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Fischer DL, et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation employs trkB signaling for neuroprotection and functional restoration. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:6786–6796. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2060-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Miller, K. M. et al. Striatal afferent BDNF is disrupted by synucleinopathy and partially restored by STN DBS. J. Neurosci.10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1952-20.2020 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 145.Grundemann J, Schlaudraff F, Liss B. UV-laser microdissection and mRNA expression analysis of individual neurons from postmortem Parkinson’s disease brains. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;755:363–374. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-163-5_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.