Abstract

Background

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) occurring because of an abnormal site of embryo implantation is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality if not timely diagnosed and intervened. To avert the increase in the rates of EP through in vitro fertilization cycles as compared to spontaneous conception, fertility experts have resorted to multiple measures, of which the most studied is shifting to frozen embryo transfer (ET) in place of fresh transfer. The aim of this study was to evaluate the difference in the risk of ectopic implantation in women undergoing fresh versus frozen-thawed ETs.

Methods

It was a retrospective single-center cohort study wherein 802 of the 853 patients who underwent ET during the study period were analyzed. These patients were further subdivided into fresh transfer group (n = 339) and frozen transfer group (n = 443). The primary outcome measure was to study the difference in EP rates in the two groups and the secondary outcome measure was to analyze the clinico-therapeutic profile of the two subgroups of EPs.

Results

Of the 802 women who underwent ETs, 19 women had an ectopic implantation with an overall incidence of 2.3%. Among the 19 EPs, there were eight EPs (2.23%) in the fresh transfer group and 11 EPs (2.48%) in the frozen transfer group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The clinico-therapeutic profile of the patients was comparable in both the groups.

Conclusion

Frozen ET cycle does not mandatorily reduce the incidence of EP in spite of the maintenance of the intrauterine milieu compared to a stimulated cycle. Larger and more robust studies are needed for recommending frozen ET cycle as a preventive modality for EP.

Keywords: Fresh transfer, Frozen embryo transfer, Ectopic pregnancy

Introduction

Since the first ectopic pregnancy (EP) reported after in vitro fertilization (IVF) by the pioneers of IVF, Steptoe and Edwards in 1976, this first trimester pregnancy complication has been a cause of concern for all fertility specialists.1 The use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) has been found to increase the risk of EP compared to spontaneous conceptions and the rates have been depicted to vary from 0.8% to 8.6%.2, 3, 4 Various risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms have been postulated for this abnormal embryo implantation ranging from pelvic inflammatory disease, tubal pathology, previous pelvic surgery, to uterine cavity abnormalities.5,6 In addition to the primary risk factors for infertility, the altered milieu associated with assisted reproduction has also been elucidated to further increase the risk of ectopic implantation. Some of the other hypotheses postulated are as follows: increased uterine contractions because of ovarian stimulation; dysfunction of the uterine musculature because of high progesterone levels; and factors associated with embryo transfer (ET) technique, such as site of placement of the embryo, technical expertise in loading, and transfer per se.7,8

Frozen embryo transfer (FET) is a technique wherein the embryos that were frozen/vitrified after an IVF cycle are warmed/thawed and then transferred into the uterus either in a natural cycle or after endometrial preparations by hormones. Historically, FET was carried out in the event of failure to conceive with a fresh IVF cycle and in addition, to decrease the incidence of ovarian hyper stimulation syndrome (OHSS) for ‘hyper responders,’ other patients at risk for OHSS or any contraindication to a fresh transfer.9 As multiple studies and data from various workers have proved FET to be as effective as fresh ET at achieving clinical pregnancy rates, live birth rates, implantation rates, and birth weights, this modality has become the order of the day.9 In addition to the aforementioned indications and advantages, FET is also being postulated by many researchers to decrease the EP rates as it simulates natural conception intrauterine environment. However, there are conflicting data on the patient.

To contribute to the existing literature and to analyze the hypotheses that the FET cycles are associated with decreased EP rates, we carried out a retrospective cohort study to judge the prevalence of EP after IVF-ET at the ART center of a tertiary care hospital in India. Rates of EP were compared after fresh versus frozen ET and to compare the clinico-therapeutic profile in terms of treatment protocol of EPs after fresh versus frozen ET after IVF.

Materials and methods

It was a retrospective single-center cohort study carried out over a period of 18 months from 1 January 2017 to 30 June 2018 after obtaining approval from the institutional review board. All women who underwent ETs during this period formed the study group; however, women who had a heterotopic gestation or a chemical pregnancy after ET were excluded from the statistical analysis. In addition, women who did not follow-up at our center after ET were excluded. Patients who underwent fresh ET formed group A, whereas group B comprises patients who were taken up for FET.

All patients who underwent fresh cycles had their controlled ovarian stimulation either by the long GnRH agonist protocol or by the antagonist protocol depending on the patient profile. Pituitary down regulation for long protocol was achieved by daily subcutaneous injection of triptorelin acetate 0.1 mg (Decapeptyl; Ferring) starting at the midluteal phase of the preceding cycle. When complete pituitary desensitization was confirmed by a low plasma estradiol (E2) level of ∼30 pg/mL and a luteinizing hormone (LH) level of ∼2 mIU/mL, ovarian stimulation was started using recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (rFSH) (Gonal-f; Serono). In the antagonist protocol, ovarian stimulation was started using rFSH from second day of the menstrual cycle and antagonist cetrorelix acetate 0.25 mg (Cetrotide; Merck) was started once the follicles reached a diameter of 14 mm. Recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (250 μg; Ovidrel; Serono) was used for ovulation trigger when three leading follicles reached a mean diameter of 18 mm in both the protocols. Oocytes were retrieved transvaginally 34–36 h after hCG administration.

Fertilization of the oocytes took place either by IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), according to the sperm parameters and indication of IVF. The oocytes were incubated in fertilization medium (Vitrolife, Sweden) and fertilized 3–4 h after retrieval. The fertilized oocytes were then continuously cultured in cleavage medium for two more days. Two to three best-quality embryos were transferred on day 2 or day 3 after oocyte retrieval. The additional good-quality embryos were cryopreserved by vitrification for subsequent FET cycles. In cases of hyper responders or other contraindications for fresh transfer, the embryos were vitrified on day 3 at eight-celled stage.

The FET cycles were carried out as hormone replacement treatment (HT) cycles. For the HT cycles after performing a baseline transvaginal ultrasound on second day of the menstrual cycle, oral estradiol valerate (Progynova; Bayer) was commenced at a dose of 4 mg/day from cycle days 2–8, and 6 mg/day from days 9–12. Transvaginal ultrasound was performed from day 13 to assess the endometrial thickness; the estradiol dosage was adjusted based on the endometrial thickness. Hundred milligrams of progesterone intramuscularly were administered when the endometrium reached a thickness of ≥7 mm. In addition, tablet dydrogesterone (Duphaston; Abbott) 10 mg twice a day was also started on the same day and oral estradiol was continued. Embryo transfer was performed either on the third or fourth day, that is, after 2 or 3 days of progesterone administration under transabdominal ultrasound guidance. The confirmation for the success or the occurrence of pregnancy was done through measurement of serum beta–human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).

As a protocol, serum β-hCG was assayed 15 days after ET. Serum β-hCG concentrations were measured in the laboratory of our hospital using chemiluminescent microparticle enzyme immunometric assay for the total β-hCG molecule. The test had been standardized according to the Third International Standard for Chorionic Gonadotropin from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (75/537).

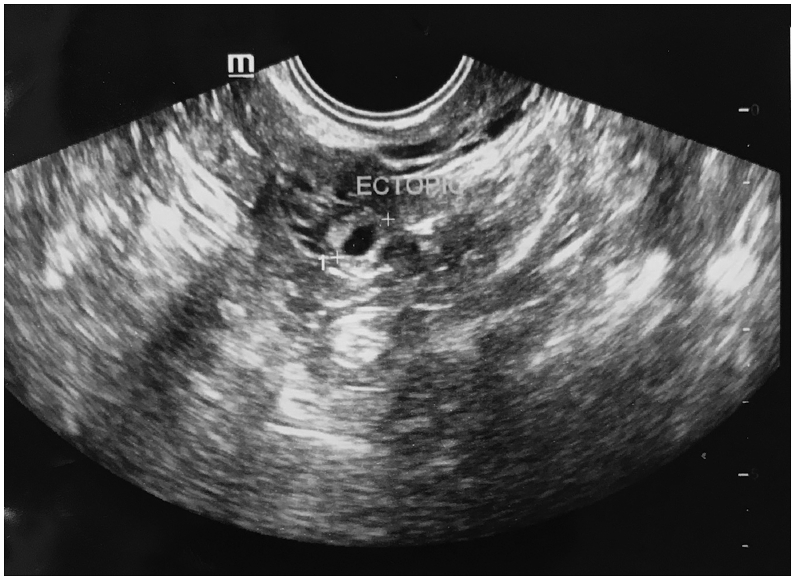

Pregnancy or positive IVF status was said to have occurred when the β-hCG level was ≥50 IU/L. If the day 16 β-hCG test was positive, but 200 mIU/mL, a second β-hCG concentration was performed 48 h later with an aim to assist in predicting a viable intrauterine pregnancy or to assist in evaluating a possible EP. An EP was defined when a pregnancy was confirmed by β-hCG and accompanied by sonographic visualization of an extrauterine gestational sac (Fig. 2; including any heterotopic gestations) or with an empty uterine cavity and increasing hCG level10 However, the first β-hCG value was considered for the statistical analysis.

Fig. 2.

Transvaginal picture of an ectopic pregnancy.

Our primary outcome measure was to study the EP rates in the two groups, that is, fresh versus frozen ET and the secondary outcome measure was to the analyze the clinico-therapeutic profile of the two subgroups of EPs in terms of treatment protocol.

Statistical analysis

All data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 13.0 (SPSS; IBM). The data were analyzed to compare fresh with frozen ET cycles. The differences in outcomes between the two groups were analyzed using Fischer exact test. A P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 853 ETs occurred during the study period; however, 802 ETs comprised the study group and 51 ETs were excluded as per the inclusion and exclusion criteria (17 chemical pregnancies, 2 heterotopic gestation, and 32 lost to follow-up). A total of 339 women underwent fresh transfers (group A), with 170 women having a positive β-hCG, whereas 210 women were conceived among the 443 patients who underwent FET cycle (group B). Thus, the overall pregnancy rate of the study group was 47.38%, with 47.34% in the fresh group and 47.4% in the FET group. Thus, there was no difference in the pregnancy rate per transfer in both the groups. Of these 802 ETs, 19 resulted in an EP making an overall EP rate of 2.3% per transfer.

Among the 19 EPs, there were eight EPs in group A and eleven EPs in group B, which amounts to 2.23% after fresh transfer and 2.48% after FET (Fig. 1), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the study group patients.

The demographic profile in terms of age, duration of infertility, cause of infertility, and history of previous ectopic of the two study groups as depicted in Table 1 were found to be comparable. It is evident that the major cause of infertility in both the ectopic groups was tubal factor.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the two study groups.

| Parameter | Group A (n = 08), fresh transfer | Group B (n = 11), frozen transfer | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.88 ± 2.80 | 30.09 ± 4.13 | 0.482 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.0 ± 16.3 | 22.6 ± 2.2 | 0.566 |

| Duration of infertility (years) | 5.75 ± 1.488 | 7.82 ± 2.822 | 0.036 |

| History of ectopic | 3 | 1 | 0.455 |

| Cause of infertility | |||

| Tubal factor (%) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (36.3) | 0.603 |

| Endometriosis (%) | 2 (25) | 2 (18.1) | 0.546 |

| Male factor (%) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (18.1) | 0.058 |

| PCOS (%) | 2 (25) | 2 (18.1) | 0.547 |

| Unexplained (%) | 0 | 1 (9.09) | 0.623 |

BMI, body mass index; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

Table 2 demonstrates that all the eight EPs in group A were managed medically with multi-dose protocol; however, two had failed medical management and thus resorted to secondary surgery. However, in the FET group, one patient required upfront primary surgery as she was not hemodynamically stable but the rest 10 of them were treated successfully by medical management. In the medical management group, two were treated by single-dose protocol and rest by multi-dose protocol. Thus, the therapeutic profiles of both the groups were also similar. The first mean β-hCG of both the groups was also similar. All the study group patients underwent transfer at cleavage stage and primarily on day 3, that is, at eight-celled stage, except one lady in the fresh transfer group who underwent a four-celled ET.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinico-therapeutic profile of the two subgroups.

| Parameter | Group A (n = 8) | Group B (n = 11) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of embryos transferred | |||

| 2 (4 cell) | 1 (17.5%) | 0 | NS |

| 2 (8 cell) | 2 (25%) | 3 (27.3%) | NS |

| 3 (8 cell) | 5 (62.5%) | 8 (72.7%) | NS |

| Mean β-hCG (mIU/mL) | 386.654 | 322.256 | NS |

| Management protocol | |||

| Single-dose methotrexate | 0 | 2 (18.2%) | NS |

| Multi-dose methotrexate | 8 (100%) | 8 (72.7%) | NS |

| Primary surgery | 0 | 1 (9.1%) | NS |

| Failed medical management with secondary surgery | 2 | 0 | NS |

Discussion

Failure of implantation in the endometrial cavity as represented by an EP remains a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the first trimester of pregnancy.11 This abnormal implantation has been found to be more in pregnancies resulting from IVF as compared to spontaneous conception and the incidence varies from 0.8% to 8.6%.2, 3, 4 In our center, we found the EP rate in the post-IVF pregnancies to be 2.3% during the study period, which is in congruence with the global data. Analyzing the various IVF procedures has given the insight for this abnormal implantation, and the most convincing hypothesis was difference in the hormonal or biochemical environment within the uterus during ET and implantation, which increases the risk of EP.7,8,12

In an effort to decrease the EP rates and counteract the altered hormonal milieu that occurs during IVF, fertility experts are exploring the plausibility of resorting to FET in place of fresh ET. Fresh ET occurs in an environment that is not physiological, whereas frozen-thawed ET takes place in a uterine environment that closely mimics what occurs during spontaneous conception.

Various studies have compared the risk of EP in fresh and frozen-thawed IVF cycles and few demonstrated the protective effect of FET for EP.13,14 After the cue, we too analyzed our data; however, we found that the EP rate in the two subgroups was similar (2.23% versus 2.48%), so did the data from Belgian studies during the period 2002–2012, which claimed no statistically significant difference in EP in fresh versus frozen-thawed cycles.15 In contrast, earlier workers in their studies found higher rates of EP with FET cycles. Bownan and Smaks on analyzing their work concluded higher EP rates in FET cycles with odds ratio of 2.24, so did Johnson et al. and Wennerholm et al.16, 17, 18

To analyze the various confounding factors for occurrence of an EP, different workers have compared the fresh versus frozen cycles in terms of mode of fertilization, stage at which ET was performed (cleavage versus blastocyst), and even ethnicity and cause of infertility. Londra et al.19 compared the risk of EP after fresh blastocyst ET and frozen-thawed blastocyst transfers in patients undergoing IVF and found that ET in cycles without exogenous hormones for hyperstimulation, such as frozen or donor cycles, were associated with lower rates of EP compared with fresh autologous cycles. Li et al.20 on the other hand compared the difference in occurrence of EP as per fertilization strategy, that is, IVF and ICSI and found that the incidence of EP was more in fresh ICSI-ET than IVF-ET cycles; however, there was no difference in the EP in frozen-thawed cycle whether the cycle was from IVF or ICSI. However, neither did we stratify our patients in terms of fertilization strategy nor studied the rates in blastocyst transfer as we had carried out cleavage stage transfers only (Table 2). As seen in previous works, Londra et al. suggested that race or ethnicity and tubal infertility were associated with increased odds of EP in autologous cycles.19,21 Differences in the EP rates as per ethnicity require more robust and bigger studies but tubal factor as an independent risk factor has been proven whether spontaneous conception or IVF.19,22 In the present study too, the major cause of infertility in both the ectopic subgroups was tubal.

Meta-analysis on the same patient by both Rogue et al. and Acharya et al. has shown similar pregnancy outcome with both fresh as well as frozen ET cycles. As per these workers, the change in the hormonal environment of the uterine cavity does not seem to increase or decrease the EP rate, so did our analysis reveal.9,23

Although the latest works have been in favor of FET for the prevention of EP, which we did not find in our analysis but it might be due to the small number of patients and its retrospective nature, which is the limitation of our study. Probably extending the study over a larger period could have given a better insight of the difference in EP rate in the two subgroups. However, the novelty of our study was studying the therapeutic profile of these EPs and there was no significant difference in their treatment response. Latest studies have implicated higher progesterone levels in the late follicular levels as detrimental to implantation rates by causing abnormal uterine motility and ciliary malfunction, which in themselves are theoretically risk factors for EP. Thus, these parameters too can guide whether to do a fresh ET or an FET.24,25

Conclusion

Fresh transfer per se should not be a complete no to prevent ectopic implantation. A holistic approach should be taken while deciding in favor or against a fresh ET. FET may be a first-line treatment modality to a subgroup of patients like hyperesponders and at risk for OHSS but more studies are required to make it a recommended preventive modality for EP after IVF.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Steptoe P.C., Edwards R.G. Reimplantation of a human embryo with subsequent tubal pregnancy. Lancet. 1976;1:880–882. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decleer W., Osmanagaoglu K., Meganck G., Devroey P. Slightly lower incidence of ectopic pregnancies in frozen embryo transfer cycles versus fresh in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer cycles: a retrospective cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng L.Y., Lin P.Y., Huang F.J. Ectopic pregnancy following in vitro fertilization with embryo transfer: a single-center experience during 15 years. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milki A.A., Jun S.H. Ectopic pregnancy rates with day 3 versus day 5 embryo transfer: a retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2003;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Refaat B., Dalton E., Ledger W.L. Ectopic pregnancy secondary to in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer: pathogenic mechanisms and management strategies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:30. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0025-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L.L., Chen X., Ye D.S. Misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis for ectopic and heterotopic pregnancies after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol - Med Sci. 2014;34:103–107. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lesny P., Killick S.R. The junctional zone of the uterus and its contractions. BJOG. 2004;111:1182–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paltieli Y., Eibschitz I., Ziskind G., Ohel G., Silbermann M., Weichselbaum A. High progesterone levels and ciliary dysfunction—a possible cause of ectopic pregnancy. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2000;17:103–106. doi: 10.1023/A:1009465900824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roque M. Fresh embryo transfer versus frozen embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnhart K., van Mello N.M., Bourne T. Pregnancy of unknown location: a consensus statement of nomenclature, definitions, and outcome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:857–866. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnhart K.T. Early pregnancy failure: beware of the pitfalls of modern management. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1061–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourgain C., Devroey P. The endometrium in stimulated cycles for IVF. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:515–522. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapiro B.S., Daneshmand S.T., de Leon L., Garner F.C., Aguirre M., Hudson C. Frozen-thawed embryo transfer is associated with a significantly reduced incidence of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1490–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishihara O., Kuwahara A., Saitoh H. Frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer reduces ectopic pregnancy risk: an analysis of single embryo transfer cycles in Japan. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1966–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decleer W., Osmanagaoglu K., Meganck G., Devroey P. Slightly lower incidence of ectopic pregnancies in frozen embryo transfer cycles versus fresh in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer cycles: a retrospective cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jee B.C., Suh C.S., Kim S.H. Ectopic pregnancy rates after frozen versus fresh embryo transfer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68:53–57. doi: 10.1159/000213048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson N., McComb P., Gudex G. Heterotopic pregnancy complicating in vitro fertilization. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;38:151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1998.tb02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wennerholm U.B., Bergh C., Hamberger L., Westlander G., Wikland M. Wood M. Obstetric outcome of pregnancies following ICSI, classified according to sperm origin and quality. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1189–1194. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.5.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Londra L., Caroline Moreau C., Strobino D., Jairo Garcia J., Zacur H., Zhao Y. Ectopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization: differences between fresh and frozen-thawed cycles. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M.Z., Zhao W.Q., Ren A.Q., Shi J.Z. Association of fertilization strategy and embryo transfer time with the incidence of ectopic pregnancy. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2015;(10):913–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clayton H.B., Schieve L.A., Peterson H.B., Jamieson D.J., Reynolds M.A., Wright V.C. Ectopic pregnancy risk with assisted reproductive technology procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:595–604. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000196503.78126.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang H.J., Suh C.S. Ectopic pregnancy after assisted reproductive technology: what are the risk factors? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:202. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32833848fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acharya Kelly S., Provost Meredith P., Yeh Jason S., RAcharya Chaitanya, Muasher Suheil J. Ectopic Pregnancy Rates in frozen Versus fresh embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization: A systematic Review and meta-analysis. Middle East Fertil Soc J. December 2014;vol. 19(4):233–238. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venetis C.A.1, Kolibianakis E.M., Bosdou J.K., Tarlatzis B.C. Progesterone elevation and probability of pregnancy after IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 60 000 cycles. Hum Reprod Update. 2013 Sep-Oct;19(5):433–457. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R1 Fanchin, Righini C., Ayoubi J.M., Olivennes F., de Ziegler D., Frydman R. Uterine contractions at the time of embryo transfer: a hindrance to implantation? Contracept Fertil Sex. 1998 Jul-Aug;26(7-8):498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]