Abstract

This cohort study reports the results of incorporating HIV screening into COVID-19 testing at the University of Chicago emergency department.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had negative consequences on HIV care and prevention programs, including routine HIV screening in health care settings.1 This has serious implications for the Ending the HIV Epidemic plan for the United States.2 Herein, we report the results of incorporating phlebotomy for universal HIV screening into COVID-19 testing at The University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) emergency department (ED) for the purpose of maintaining screening volumes.

Methods

The institutional review board at the UCM Medical Center granted exemption for this project because the data set analyzed contained deidentified data. We reviewed data from the Expanded HIV Testing and Linkage to Care Program, a collaboration between 13 health care centers on the South and West sides of Chicago, during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Sites include community health centers, community hospitals, and academic hospitals, including 5 EDs, all of which implemented opt-out HIV screening according to guidelines.4 Since 2016, sites perform combination HIV antigen-antibody testing and have processes for rapid linkage to care and antiretroviral initiation for patients with acute HIV infection (AHI).5 The ED at UCM designed a rapid COVID-19 testing area to seamlessly incorporate phlebotomy for HIV screening without any additional personnel. Responsibilities for test review, patient notification, and linkage to care were assigned to the HIV Care Program. Statistical analysis was an interrupted time series Poisson regression comparing the rate of AHI diagnoses per day for the 1461 days prior to January 1, 2020, and the 290 days between January 1 and October 16, 2020. Analyses were completed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), and 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

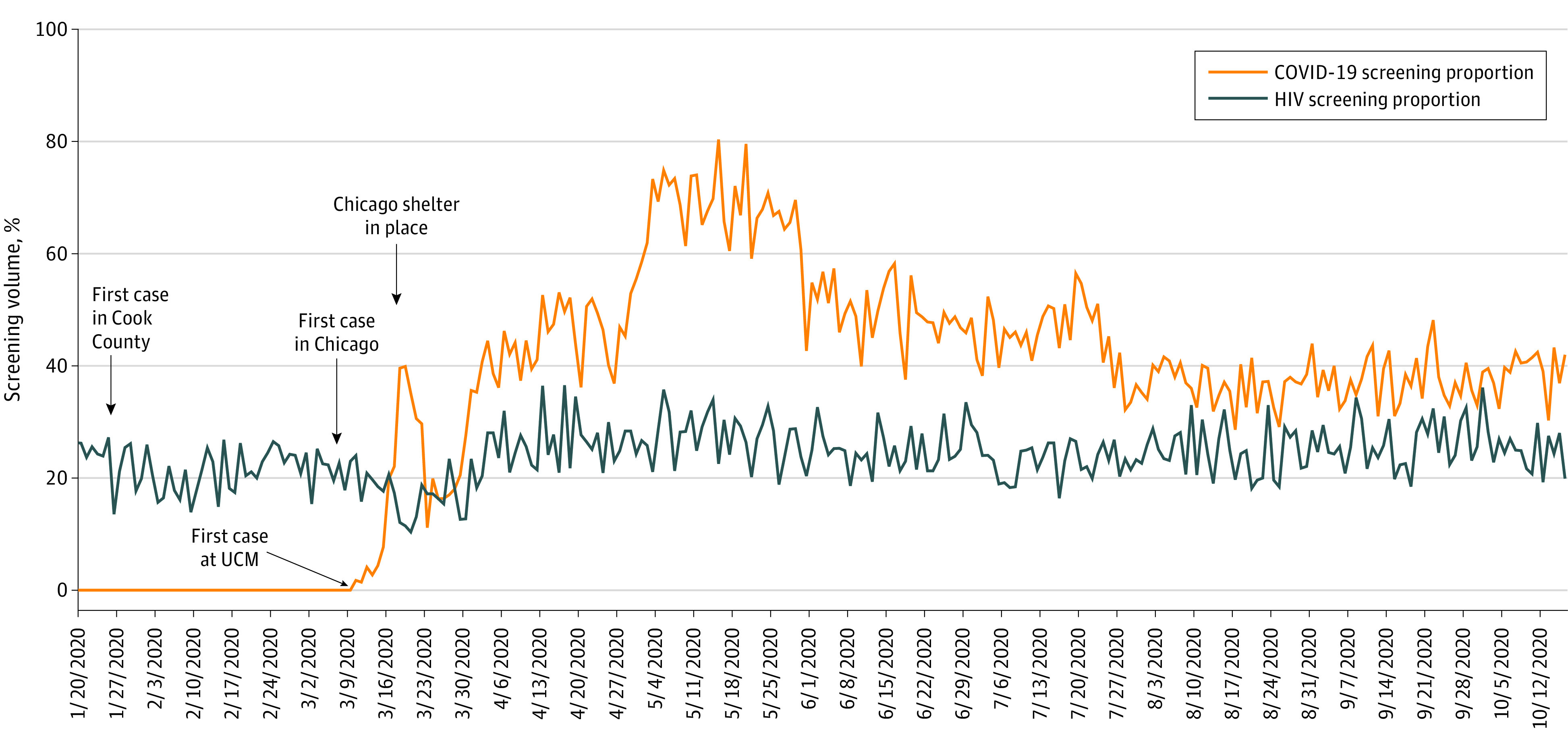

Most sites experienced significant reductions in HIV screens during the pandemic, and overall, the program saw a 49% reduction in testing events from January 1 to April 30, 2020. The ED at UCM, however, maintained HIV screening volumes throughout the pandemic (Figure) and performed 19 111 HIV screens (14 215 in the ED) between January 1 and October 16, 2020, along with 112 242 COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests (18 830 in the ED). Twelve patients were diagnosed with AHI after the first COVID-19 diagnosis in Cook County on January 24, 2020 (Table). The rate of AHI diagnoses per day was significantly higher during the pandemic compared with the prior 4 years (incidence rate ratio, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.22-4.83; P = .01). Other EDs not incorporating HIV screening into COVID-19 testing saw a 25% decrease in AHI diagnoses (incidence rate ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.26-2.14; P = .59) that was not statistically significant.

Figure. Proportion of Emergency Department Visits at UCM With HIV Screening and COVID-19 Testing During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

UCM indicates The University of Chicago Medicine.

Table. HIV Screens, New HIV Diagnoses, and Acute HIV Infections Diagnosed in the Emergency Department (ED) at UCM and Other EDsa.

| Year | No. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV screens in ED at UCM | New HIV diagnoses in ED at UCM | AHI diagnoses in ED at UCM | HIV screens in other x-TLC EDs | New HIV diagnoses at other x-TLC EDs | AHI diagnoses at other x-TLC EDs | |

| 2016 | 2837 | 18 | 5 | 16 008 | 57 | 3 |

| 2017 | 3651 | 22 | 7 | 21 175 | 53 | 8 |

| 2018 | 5748 | 39 | 4 | 21 133 | 39 | 4 |

| 2019 | 11 861 | 39 | 9 | 16 878 | 48 | 12 |

| 2020 | 14 215 | 39 | 12 | 14 470 | 32 | 4 |

Abbreviations: AHI, acute HIV infection; UCM, The University of Chicago Medicine; x-TLC, Expanded HIV Testing and Linkage to Care Program.

Dates of comparison are from January 1, 2016, through October 16, 2020.

Patients with AHI comprised 12 of 46 (26.1%) new diagnoses at UCM, the highest proportion on record. Included were 9 men (6 men who have sex with men, 2 heterosexual, and 1 undisclosed) and 3 cisgender women with a median (range) age of 25 (21-28) years. The median (range) viral load was 6 million (115 000 to >6 million) copies/mL. Eleven of 12 patients presented with symptoms consistent with COVID-19. One patient had COVID-19 infection and AHI. All were linked and initiated antiretroviral therapy by a median (range) of 1 (0-38) day from the time of PCR result but 3 (1-41) days from sample collection owing to delays in reflex PCR confirmatory testing, a result of high demands on laboratory personnel and scarcity of supplies (eg, amplification and testing trays) owing to COVID-19 testing volumes.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is superimposed on the HIV pandemic, jeopardizing progress toward HIV elimination. Routine HIV screening in health care settings is a key elimination strategy that has been negatively affected during the pandemic. A limitation to this study is that the reasons for refusal of HIV screening by patients or health care professionals are not known. Also, we do not know how many COVID-19 tests were triggered by symptoms or were screening of asymptomatic patients owing to exposures or screening of potential admissions for infection control purposes. However, we saw a considerable increase in AHI diagnoses with incorporating HIV screening into COVID-19 testing in the ED at UCM. This could be because of increased screening. Alternatively, patients with AHI may be more likely to present for care because of concern for COVID-19 infection. Finally, new transmissions may be increasing owing to disrupted HIV care and prevention efforts. Thus, HIV screening programs, particularly in EDs, should incorporate or even link HIV screening to COVID-19 testing. Modeling suggests this would reduce HIV incidence and health care costs.6

References

- 1.Krakower DS, Solleveld P, Levine K, Mayer KH. Impact of COVID-19 on HIV preexposure prophylaxis care at a Boston community health center. Poster presented at: AIDS 2020; July 6-10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV Epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844-845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bares S, Eavou R, Bertozzi-Villa C, et al. Expanded HIV testing and linkage to care: conventional vs. point-of-care testing and assignment of patient notification and linkage to care to an HIV care program. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(suppl 1):107-120. doi: 10.1177/00333549161310S113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNulty M, Cifu AS, Pitrak D. HIV screening. JAMA. 2016;316(2):213-214. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNulty M, Schmitt J, Friedman E, et al. Implementing rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy for acute HIV infection within a routine testing and linkage to care program in Chicago. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. Published online July 31, 2020. doi: 10.1177/2325958220939754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zang X, Krebs E, Chen S, et al. The potential epidemiological impact of COVID-19 on the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the cost-effectiveness of linked, opt-out HIV testing: a modeling study in six US cities. Clin Infect Dis. Published online October 12, 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]