Abstract

This prospective study investigated whether antibodies from SARS-CoV-2 immunization of nursing mothers transferred to infants as a potentially protective effect.

On December 20, 2020, Israel initiated a national vaccination program against COVID-19. One prioritized group was health care workers, many of whom are breastfeeding women.1 Despite the fact that the vaccine trial did not include this population2 and no other vaccine-related safety data had been published, breastfeeding women belonging to risk groups were encouraged to receive the vaccine.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also recommended that breastfeeding women belonging to vaccine-target groups be immunized.4 We investigated whether maternal immunization results in secretion of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies into breast milk and evaluated any potential adverse events among women and their infants.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study of a convenience sample of breastfeeding women (either exclusive or partial) belonging to vaccine-target groups who chose to be vaccinated. Participants were recruited from all of Israel between December 23, 2020, and January 15, 2021, through advertisements and social media. All participants received 2 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine 21 days apart. Breast milk samples were collected before administration of the vaccine and then once weekly for 6 weeks starting at week 2 after the first dose. Samples were kept frozen pending analysis. IgG levels were detected by the Elecsys Anti–SARS-CoV-2 S serology assay and read on the Cobas e801 analyzer with a level of more than 0.8 U/mL considered positive (La Roche Ltd) and IgA with the EUROIMMUN AG Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S Kit with an extinction ratio of samples over calibrator of more than 0.8 considered positive (Supplement). At enrollment, maternal and infant demographic information was collected, followed by weekly questionnaires coupled to breast milk collection soliciting information about interim well-being and vaccine-related adverse events. The study was approved by the Shamir Medical Center Institutional Review Board; written informed consent was obtained from mothers.

Changes in the proportion of participants with positive test results and in antibody levels during the study were evaluated using paired-sample t tests, comparing antibody levels at each point with the baseline and correcting for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. A 2-sided significance threshold was set at P < .05. Analyses were performed with R version 3.6

Results

Eighty-four women completed the study, providing 504 breast milk samples. Women were a mean (SD) age of 34 (4) years and infants 10.32 (7.3) months (Table).

Table. Maternal and Infant Characteristics.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Study participants, No. | 84 |

| Maternal features | |

| Maternal age, mean (SD), y | 34 (4) |

| No. of children, mean (SD) | 2.36 (0.98) |

| Chronic diseases | 22 (26.2) |

| Gestational diabetes | 3 (3.6) |

| First vaccine adverse effects | 47 (55.9) |

| Local pain | 40 (47.6) |

| Fatigue | 8 (9.5) |

| Fever | 0 |

| Other | 12 (14.3) |

| Second vaccine adverse effects | 52 (61.9) |

| Local pain | 34 (40.5) |

| Fatigue | 28 (33.3) |

| Fever | 10 (11.9) |

| Other | 22 (26.2) |

| Infant related features | |

| Vaginal delivery mode | 78 (92.9) |

| Infant age at time of first maternal vaccine, mean (SD), mo | 10.32 (7.31) |

| Birth week, mean (SD) | 39.01 (1.95) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 3175.27 (502.33) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 35 (41.6) |

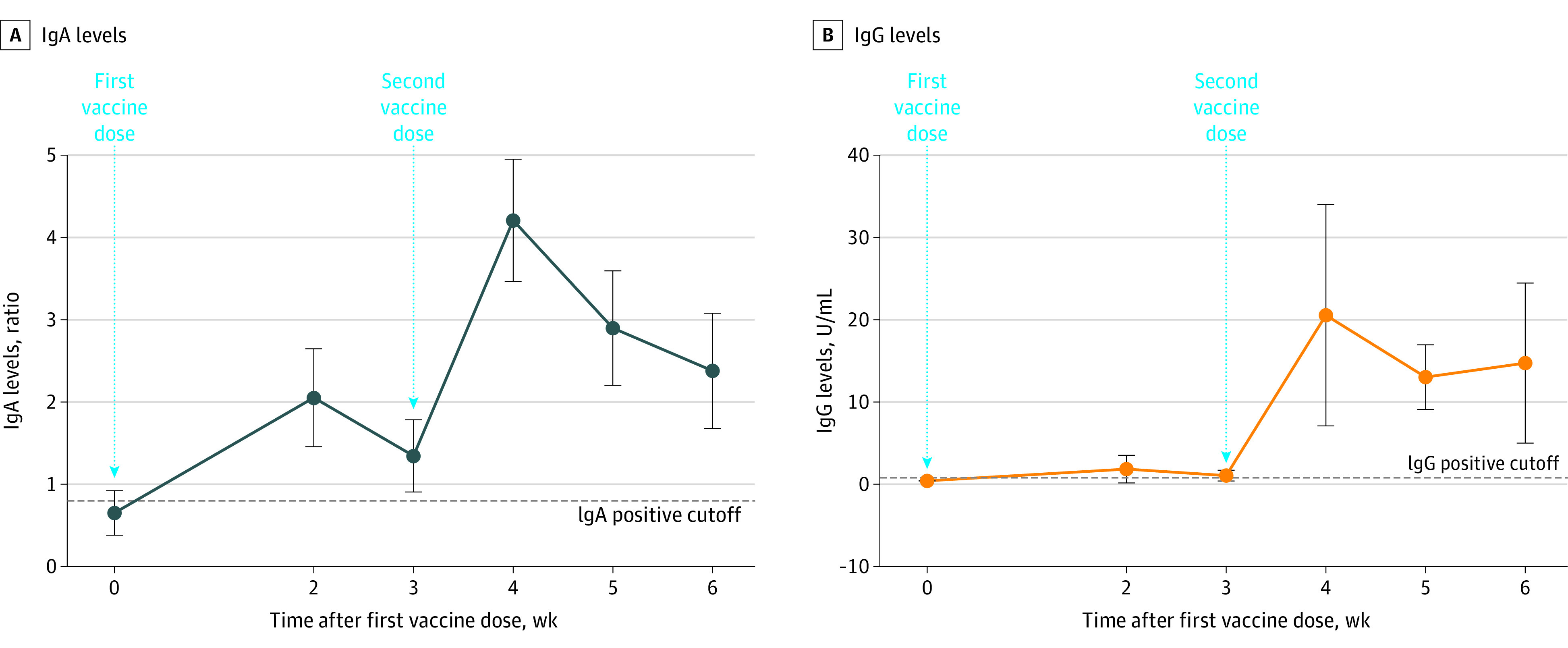

Mean levels of anti–SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA antibodies in the breast milk increased rapidly and were significantly elevated at 2 weeks after the first vaccine (2.05 ratio; P < .001), when 61.8% of samples tested positive, increasing to 86.1% at week 4 (1 week after the second vaccine). Mean levels remained elevated for the duration of follow-up, and at week six, 65.7% of samples tested positive. Anti–SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies remained low for the first 3 weeks, with an increase at week 4 (20.5 U/mL; P = .004), when 91.7% of samples tested positive, increasing to 97% at weeks 5 and 6 (Figure).

Figure. Changes in Levels of IgA and IgG in Breast Milk Over Time.

A, All the comparisons between time points are P < .001. B, The comparison point at week 4 is P = .004; at week 5, P <.001; and at week 6, P = .005.

Data points represent means; error bars, 95% CIs.

No mother or infant experienced any serious adverse event during the study period. Forty-seven women (55.9%) reported a vaccine-related adverse event after the first vaccine dose and 52 (61.9%) after the second vaccine dose, with local pain being the most common complaint (Table). Four infants developed fever during the study period 7, 12, 15, and 20 days after maternal vaccination. All had symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection including cough and congestion, which resolved without treatment except for 1 infant who was admitted for neonatal fever evaluation due to his age and was treated with antibiotics pending culture results. No other adverse events were reported.

Discussion

This study found robust secretion of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgA and IgG antibodies in breast milk for 6 weeks after vaccination. IgA secretion was evident as early as 2 weeks after vaccination followed by a spike in IgG after 4 weeks (a week after the second vaccine). A few other studies have shown similar findings in women infected with COVID-19.5 Antibodies found in breast milk of these women showed strong neutralizing effects, suggesting a potential protective effect against infection in the infant.

The study has limitations. First, no functional assays were performed. However, previous studies have showed neutralizing capacities of the same antibodies as measured for this study. Second, serum antibody testing or SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction testing were not performed, which would have provided interesting correlates.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

eMethods

References

- 1.State of Israel Ministry of Health . The COVID-19 vaccine operation launched today. State of Israel Ministry of Health; 2021. Posted December 19, 2020. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://www.gov.il/en/Departments/news/19122020-02

- 2.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. ; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Guidelines for COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant and nursing women. Guidelines in Hebrew. Published December 20, 2020. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://govextra.gov.il/media/30093/pregnancy-covid19-vaccine.pdf

- 4.Information about COVID-19 Vaccines for People who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/pregnancy.html

- 5.Pace RM, Williams JE, Järvinen KM, et al. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, antibodies, and neutralizing capacity in milk produced by women with COVID-19. mBio. 2021;12(1):1-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03192-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods