Abstract

Edible fruit plants of tropical forests are important for the subsistence of traditional communities. Understanding the most important pollinators related to fruit and seed production of these plants is a necessary step to protect their pollination service and assure the food security of these communities. However, there are many important knowledge gaps related to floral biology and pollination in megadiverse tropical rainforests, such as the Amazon Forest, due mainly to the high number of plant species. Our study aims to indicate the main pollinators of edible plants (mainly fruits) of the Amazon forest. For this, we adopted a threefold strategy: we built a list of edible plant species, determined the pollination syndrome of each species, and performed a review on the scientific literature searching for their pollinator/visitors. The list of plant species was determined from two specialized publications on Amazon fruit plants, totaling 188 species. The pollination syndrome was determined for 161 species. The syndromes most frequently found among the analyzed species were melittophily (bee pollination), which was found in 101 of the analyzed plant species (54%) and cantharophily (beetle pollination; 26 species; 14%). We also found 238 pollinator/visitor taxa quoted for 52 (28%) plant species in previous publications, with 124 taxa belonging to Apidae family (bees; 52%), mainly from Meliponini tribe (58 taxa; 47%). Knowledge about pollinators is an important step to help on preserving their ecosystem services and maintaining the productivity of fruit trees in the Amazon.

Keywords: food production, ecosystem service, bee, traditional community, sustainability

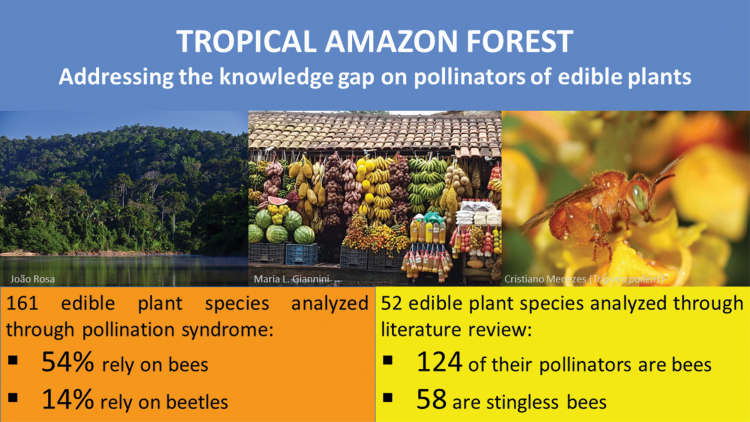

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Brazil holds the largest area covered by tropical forests in the world, and these forests are predominantly in the Amazon biome, which is home to 7,000 to 16,000 species of trees (Gomes et al. 2019). It was proposed that near 220 edible fruit-bearing plants are found only in the Amazon, corresponding to almost 50% of all fruits listed to Brazil (roughly 500 species) (Giacometti 1993). These plant species are important to the subsistence of traditional populations, which is largely based on nature-based systems characterized by small production and manual collection of food (Pinton and Emperaire 2004). However, many of the plants used by indigenous peoples and local communities in the Amazon are still poorly understood regarding their basic biology and their contribution to human well-being (Clement et al. 1982).

Most plant species require animal pollination for fruit and seed production (Ollerton et al. 2011), especially in tropical habitats, where a large number of angiosperms and a wide diversity of pollinators with specific pollination mechanisms are found (Machado and Lopes 2008). Pollination has been extensively studied because of its importance as nature’s contribution to people (NCP) (Díaz et al. 2018) and its utility for sustainable agriculture (Garibaldi et al. 2016) and to the maintenance of biocultural values (Hill et al. 2019). According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) data, 33% of human food depends to some degree on cultivated species, which are most frequently pollinated by bees (Klein et al. 2007). Costanza et al. (1997) carried out the first global assessment of the value of pollination (US$117 billion). This value was later updated (Costanza et al. 2014) and a recent review estimated the total annual value of crop pollination as corresponding to $235–$577 billion (in 2015, U.S. dollars) (IPBES 2016). For Brazil, Giannini et al. (2015a) showed that agricultural pollination had an annual value of US$12 billion (in 2013). For Pará, the second largest state of Brazil and entirely within the Amazon forest biome, the annual value of agricultural pollination (in 2016) corresponds to US$983 million (Borges et al. 2020). In addition, for some crops, flower visitors promote enhancement of fruit quality, which is an indirect benefit of extreme importance for agricultural production, increasing its market value (Giannini et al. 2015a).

Globally, bees are the main pollinators of agricultural crops (Potts 2016). From those, the importance of highly social species such as Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) (Potts et al. 2016) and stingless bees (Meliponini tribe) (Slaa et al. 2006; Giannini et al. 2015b, 2020a) is well recognized. Recent data on 23 Brazilian crops showed that 144 bee species were quoted as crop pollinators; from those, social bees comprised 63 species (44%), being Trigona Jurine, 1807 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and Melipona Illiger, 1806 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) two important genera with the highest number of species quoted (Giannini et al. 2020a).

Pollinator declines have been reported since the mid-20th century (Carson 1962, Buchmann and Nabhan 1997), and nowadays, it is clear that multiple factors can affect pollinators, mainly habitat loss, pathogens, pesticides, and climate change (Potts et al. 2010, 2016). This decline poses an important challenge for global food production (Potts et al. 2016). For Brazil, a previous study showed that the projected climate change will potentially reduce the probability of pollinator occurrence by almost 0.13 by 2050 (Giannini et al. 2017). Considering bees occurring in the Eastern Amazon, recent projections suggested a potential reduction in pollination services, especially regarding crop pollination (Giannini et al. 2020b). However, a supplementary and equally important concern is the lack of knowledge related to insects (Montgomery et al. 2020), especially in tropical areas.

Pollination data from megadiverse tropical forest habitats, such as the Amazon forest, are still scarce (Giannini et al. 2015b, Borges et al. 2020), which represents a challenge to understand crop production and anticipate the potential threat of crop pollinator deficits due to global change. This knowledge gap is critical, especially considering the rapid ongoing degradation in the Amazon forest (Nobre et al. 2016, Paiva et al. 2020), and the high number of species, and the difficulties to conduct field surveys. When analyzing large numbers of tropical plant species, studies on pollination syndromes can be useful, aiming to address the group of pollinators that is the most important for each plant species. Floral characteristics can select floral visitors that have a suitable morphology and behavior, maximizing their chance of acting as pollinators (Stang et al. 2006); those characteristics define the pollination syndrome (Fenster et al. 2004). In the last decade, studies have shown that floral morphology is an important factor in structuring pollination interactions (e.g., Stang et al. 2006, Dalsgaard et al. 2008), since floral structures are adapted to enhance efficiency of pollen vectors (Proctor et al. 1996). In spite of the generalized nature of plant-pollinator interaction (Waser et al. 1996), the pollination syndrome concept was successfully applied to assess the main pollinators in a large number of South African plant species (Johnson and Wester 2017), and in Brazilian tropical forests (Machado and Lopes 2004, Girão et al. 2007), as well seasonal forests (Kinoshita et al. 2006). It was also applied to monitoring restoration (Martins and Antonini 2016), and defining the influence of abiotic factors on flowering phenology (Cortés-Flores et al. 2017). However, determining one specific pollinator taxon, or a set of taxa, is an additional challenge, which can be addressed through a review on scientific literature considering each focused plant species.

Our objective was to indicate the main pollinators of edible plants (mainly fruit trees) of the Brazilian Amazon Tropical Forest. For this, we first built a list of Amazon fruit trees and then determined the pollination syndrome for each species. We also conducted a literature survey to determine whether any specific pollinator/visitor species was previously quoted for each plant species listed.

Materials and Methods

The list of plant species used in our study was produced from specialized literature on Amazon fruit tree species, and includes the seminal publications of Cavalcante (1996) and Silva (2011), which listed the plants consumed by traditional communities in this biome.

We determined the pollination syndrome of each plant species based on characteristics suggested by Faegri and van der Pijl (1979) and Rosas-Guerrero et al. (2014) (Table 1). The information used to identify the pollination syndromes was based on images available for each plant species, virtual herbaria sources, articles on reproductive and flowering biology, and books that address the region’s flora. Additional details were also obtained, such as the flowering period of each plant species (phenology), plant habit, potential ethnobotanical uses for local Amazon communities, and if species are exotic or native on Brazil.

Table 1.

Pollination syndromes and their characteristics (modified from Faegri and van der Pijl 1979 and Rosas-Guerrero et al. 2014).

| Pollination syndrome | Aperture | Color | Odor strength / type | Shape | Orientation | Size / symmetry | Nectar guide / sexual organ | Reward |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemophily / wind | Diurnal; nocturnal | Green whitish | Imperceptible | Brush | Upright | Amorpho | Absent | Absent |

| Cantharophily /beetles | Diurnal; nocturnal | Brown; green; white | Strong /fruity; musky | Dish | Horizontal; upright | Large /radial | Absent/exposed | Food tissue; heat; nectar; pollen |

| Entomophily / insecta | Diurnal; nocturnal | Bright colors | Nectar; pollen | |||||

| Phalaenophily / moths | Nocturnal | White | Moderate; strong / sweet | Bell; brush; tubo | Horizontal; pendent / upright | Medium; large; huge / radial | Absent/ closed | Nectar |

| Melittophily /bees | Diurnal | Blue; pink; purple; white; yellow | Imperceptible; weak /fresh; sweet | Bell; dish; tubo; flag; gullet | Horizontal; pendent; upright | Small; medium; large / bilateral; radial | Absent; present/ closed; exposed | Fragrance; nectar; oil; pollen; resin |

| Myophily / flies | Diurnal | Brown; green; white; yellow | Imperceptible; weak /fruity; sour | Bell; dish | Horizontal; upright | Small / radial | Absent; present / exposed | Nectar; pollen |

| Ornithophily / hummingbirds | Diurnal | Orange; pink; red; yellow | Imperceptible | Brush; tubo; flag; gullet | Horizontal; pendent; upright | Medium; large / bilateral; radial | Absent/exposed | Nectar |

| Psychophily / buterflies and diurnal moths | Diurnal | Blue; orange; pink; red; yellow | Weak / fresh | Bell; brush; tube | Horizontal; upright | Small; medium; large / radial | Absent; present / closed | Nectar |

| Chiropterophily / bats | Nocturnal | Dark red; green; white | Moderate; strong / fruity; musky; sour | Bell; brush; dish; gullet | Horizontal; pendent; upright; (far ground) | Large; huge / bilateral; radial | Absent/exposed | Food tissue; nectar; pollen |

aThe entomophily syndrome is formed by a set of characteristics that characterize flowers attractive to several insects, and it is not possible to determine a particular insect group.

A survey of previous publications that reported visitors or effective pollinators of plant species quoted here was also conducted. We searched in the Scopus database the scientific name of each plant species listed combined with ‘pollination’ OR ‘pollinator’ OR ‘visitor’. As our aim was to identify potential pollinators occurring on Amazon associated to each of the listed plant, we considered only studies conducted in the Amazon biome. If any pollinator/visitor species was quoted in the reference, we inserted this information on our database.

Taxonomy classification for plants and bees followed two Brazilian biodiversity repositories. For plant species, we used Flora do Brasil (http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/) and for bee species we used Catálogo de Abelhas Moure (http://moure.cria.org.br/; classification according to Moure et al. 2007).

Results

We compiled a list of 188 species (Table 2). These species belong to 44 botanical families, and the families Arecaceae and Sapotaceae were the most frequent, with 22 and 16 species, respectively. Most species are trees (148 species; 79%). Among the 188 species, 147 species are native to Brazil and 41 species are exotic. Of the total number of species of fruit plants listed, we determined the pollination syndrome for 161 species; we could not find information for the remaining species (27 species; 14%).

Table 2.

Pollination syndrome of edible plants from Brazilian Amazon

| Family | Scientific name | Brazilian vernacular name | Syndrome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arecaceae | 1. Acrocomia sclerocarpa Mart. | Mucajá | Undefined |

| Opilinaceae | 2. Agonandra brasiliensis Miers ex Benth & Hook. F. | Agonandra | Undefined |

| Arecaceae | 3. Aiphanes aculeata Willd. | Cariota-de-espinho | Cantharophily |

| Rubiaceae | 4. Alibertia edulis (Rich.) Rich. Ex DC. | Puruí | Phalenophily |

| Lecitidaceae | 5. Allantoma lineata (Mart. & Berg) Miers | Ceru | Mellitophily |

| Apocynaceae | 6. Ambelania acida Aubl. | Papino-do-Mato | Phalenophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 7. Anacardium giganteum Hanc. Ex Engl. | Cajuí | Mellitophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 8. Anacardium humile A. St.-Hil | Cajuzinho-do-campo | Mellitophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 9. Anacardium microcarpum Ducke | Caju-do-Campo | Mellitophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 10. Anacardium negrense Pires & Froés ex Black & Pires | Cajutim | Mellitophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 11. Anacardium occidentale L. | Caju | Mellitophily |

| Bromeliaceae | 12. Ananas comosus (L.) Merril | Abacaxi | Ornithophily |

| Annonaceae | 13. Annona crassiflora Mart. | Araticum-do-cerrado | Cantharophily |

| Annonaceae | 14. Annona densicoma Mart. | Araticum-do-Mato | Cantharophily |

| Annonaceae | 15. Annona montana Macf. | Araticum | Cantharophily |

| Annonaceae | 16. Annona muricata L. | Graviola | Cantharophily |

| Annonaceae | 17. Annona squamosa L. | Ata | Cantharophily |

| Leguminosae | 18. Arachis hypogaea L. | Amendoim | Mellitophily |

| Myrsinaceae | 19. Ardisia panurensis Mez | Cururureçá | Mellitophily |

| Moraceae | 20. Artocarpus altilis (S. Parkinson) Fosb. | Fruta-Pão | Mellitophily |

| Moraceae | 21. Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. | Jaca | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 22. Astrocaryum aculeatum G. Mey. | Tucumã-do-Amazonas | Undefined |

| Arecaceae | 23. Astrocaryum jauari Mart. | Jauari | Undefined |

| Arecaceae | 24. Astrocaryum murumuru Mart. | Murumuru | Undefined |

| Arecaceae | 25. Astrocaryum vulgare Mart. | Tucumã-do-Pará | Cantharophily |

| Oxalidaceae | 26. Averrhoa bilimbi L. | Limão-de-Caiena | Mellitophily |

| Oxalidaceae | 27. Averrhoa carambola L. | Carambola | Mellitophily |

| Arecaceae | 28. Bactris gasipaes Kunth | Pupunha | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 29. Bactris maraja Mart. | Marajá | Cantharophily |

| Moraceae | 30. Bagassa guianensis Aubl. | Tatajuba | Mellitophily |

| Melastomataceae | 31. Bellucia grossularioides (L.) Triana | Araçá-de-Anta | Mellitophily |

| Lecitidaceae | 32. Bertholletia excelsa Bonpland | Castanha-do-Pará | Mellitophily |

| Bixaceae | 33. Bixa orellana L. | Urucum | Mellitophily |

| Malvaceae | 34. Bombacopis glaba (Pasquale) Robyns | Castanha-do-maranhão | Mellitophily |

| Apocynaceae | 35. Bonafousia longituba Markgr. | Paiuetu | Phalenophily |

| Rubiaceae | 36. Borojoa sorbilis (Ducke) Cuatr. | Puruí-Grande | Phalenophily |

| Malpighiaceae | 37. Bunchosia armeniaca (Cav.) DC | Caferana | Mellitophily |

| Malpighiaceae | 38. Byrsonima amazonica Griseb. | Muruci-Vermelho | Mellitophily |

| Malpighiaceae | 39. Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Rich. | Muruci | Mellitophily |

| Malpighiaceae | 40. Byrsonima crispa Jussieu | Muruci-da-Mata | Mellitophily |

| Malpighiaceae | 41. Byrsonima lancifolia Jussieu | Muruci-da-Capoeira | Mellitophily |

| Malpighiaceae | 42. Byrsonima verbascifolia (L.) Rich. Ex Jussieu | Muruci-Rasteiro | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 43. Campomanesia lineatifolia Ruiz & Pavon | Guabiraba | Mellitophily |

| Caryocaceae | 44. Carica papaya L. | Mamão | Phalenophily |

| Caryocaraceae | 45. Caryocar brasiliense Camb. | Pequi | Chiropterophily |

| Caryocaceae | 46. Caryocar villosum (Aubl.) Pers. | Piquiá | Chiropterophily |

| Euforbiaceae | 47. Caryodendron amazonicum Ducke | Castanha-de-Porco | Undefined |

| Leguminosae | 48. Cassia leiandra Benth. | Marimari | Mellitophily |

| Hippocrateaceae | 49. Cheiloclinium cognatum (Miers) A.C. Smith | Uarutama | Mellitophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 50. Chrysobalanus icaco L. | Ajuru | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 51. Chrysophyllum cainito L. | Camitié | Myophily |

| Curcubitaceae | 52. Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | Melancia | Mellitophily |

| Rutaceae | 53. Citrus spp. | Citrus | Mellitophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 54. Couepia bracteosa Benth. | Pajurá | Mellitophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 55. Couepia edulis (Prance) Prance | Castanha-de-Cutia | Mellitophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 56. Couepia longipendula Pilger | Castanha-de-Galinha | Mellitophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 57. Couepia paraensis (Mart. & Zucc.) Benth. | Pirauxi | Mellitophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 58. Couepia subcordata Benth. Ex Hook.f. | Umarirana | Mellitophily |

| Apocynaceae | 59. Couma guianensis Aubl. | Sorva | Mellitophily |

| Apocynaceae | 60. Couma macrocarpa Barb. Rodr. | Sorva-Grande | Mellitophily |

| Apocynaceae | 61. Couma utilis (Mart.) Muell. Arg. | Sorvinha | Phalenophily |

| Curcubitaceae | 62. Cucumis melo L. | Melão | Mellitophily |

| Fabaceae | 63. Dipteryx alata Vogel | Baru | Mellitophily |

| Humiriaceae | 64. Duckesia verrucosa (Ducke) Cuatr. | Uxicuruá | Undefined |

| Annonaceae | 65. Duguetia marcgraviana Mart. | Pindaeua | Cantharophily |

| Annonaceae | 66. Duguetia stenantha R. E. Fries | Jaboti | Cantharophily |

| Rubiaceae | 67. Duroia macrophylla Huber | Cabeça-de-Urubu | Phalenophily |

| Rubiaceae | 68. Duroia saccifera Hook. F. ex Schum. | Puruí-do-Mata | Phalenophily |

| Sapotaceae | 69. Ecclinusa guianensis Eyma | Guajaraí | Undefined |

| Arecaceae | 70. Elaeis oleifera (Kunth) Cortés | Caiaué | Undefined |

| Humiriaceae | 71. Endopleura uchi (Huber) Cuatrecasas | Uxi | Undefined |

| Vochysiaceae | 72. Erisma japura Spruce ex. Warm. | Japurá | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 73. Eugenia brasiliensis Lam. | Grumixama | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 74. Eugenia patrisii Vahl | Ubaia | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 75. Eugenia stipitata McVaugh | Araçá-Boi | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 76. Eugenia uniflora L. | Ginja | Mellitophily |

| Arecaceae | 77. Euterpe oleraceae Mart. | Açai | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 78. Euterpe precatoria Mart. | Açai-do-Amazonas | Cantharophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 79. Exellodendron coriaceum (Berth.) Prance | Catanharana | Undefined |

| Salicaceae | 80. Flacourtia jangomas (Lour.) Raeusch. | Ameixa-de-Madagascar | Mellitophily |

| Annonaceae | 81. Fusaea longifolia (Aubl.) Safford | Fusaia | Cantharophily |

| Rubiaceae | 82. Genipa americana L. | Jenipapo | Mellitophily |

| Gnetaceae | 83. Gnetum spp. | Ituá | Undefined |

| Malvaceae | 84. Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. | Mutamba | Mellitophily |

| Apocynaceae | 85. Hancornia speciosa Gomes | Mangaba | Phalenophily |

| Moraceae | 86. Helicostylis tomentosa (Poepp. & Endl.) Rusby | Inharé | Undefined |

| Humiriaceae | 87. Humiria balsamifera Aubl. | Umiri | Mellitophily |

| Fabaceae | 88. Hymenaea stigonocarpa Mart. Ex Haine | Jatobá-do-cerrado | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 89. Hymenea courbaril L. | Jutaí | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 90. Inga alba (Sw.) Willd. | Inga-Turi | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 91. Inga capitata Desv. | Ingá-Costela | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 92. Inga cinnamomea Spruce ex Benth. | Ingá-Açu | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 93. Inga edulis Mart. | Ingá-Cipó | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 94. Inga fagifolia (L.) Willd. Ex Benth. | Ingá-Cururu | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 95. Inga heterophylla Willd. | Ingá-Xixica | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 96. Inga macrophylla Humb. & Bonpl. Ex Willd | Ingapéua | Chiropterophily |

| Leguminosae | 97. Inga velutina Willd. | Ingá-de-Fogo | Chiropterophily |

| Caryocacee | 98. Jacaratia spinosa (Aubl.) A. DC. | Jaracatiá | Phalenophily |

| Sapotaceae | 99. Labatia macrocarpa Mart. | Cabeça-de-Macaco | Undefined |

| Apocynaceae | 100. Lacmellea arborescens (Muell. Arg.) Monach. | Tucujá | Phalenophily |

| Quiinaceae | 101. Lacunaria jenmani (Oliv.) Ducke. | Moela-de-Mutum | Mellitophily |

| Lecitidaceae | 102. Lecythis pisonis Cambess.subesp usitata (Miers) Mori & Prance | Sapucaia | Mellitophily |

| Arecaceae | 103. Leopoldina major Wallace | Jará-Açu | Undefined |

| Crisobalanaceae | 104. Licania tomentosa (Benth.) Frit. | Oiti | Mellitophily |

| Moraceae | 105. Maclura tinctoria (L.) D.Don ex Steud | Taiuva | Undefined |

| Malpiguiaceae | 106. Malpighia punicifolia L., M. retusa Benth. | Acerola | Mellitophily |

| Clusiaceae | 107. Mammea americana L. | Abricó | Mellitophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 108. Mangifera indica L. | Manga | Myophily |

| Sapotaceae | 109. Manilkara huberi (Ducke) Chevalier | Maçaranduba | Myophily |

| Sapotaceae | 110. Manilkara zapota (L.) P. Royen | Sapotilha | Mellitophily |

| Arecaceae | 111. Mauritia flexuosa L.f. | Miriti | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 112. Mauritiella armata (Mart.) Burr. | Caraná (buriti) | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 113. Maximiliana maripa (Aubl.) Drude | Inajá | Cantharophily |

| Sapindaceae | 114. Melicoccus bijugatus Jacq. | Pitomba-das-Guianas | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 115. Micropholis acutangula (Ducke) Eyma | Abiu-carambola | Mellitophily |

| Melastomataceae | 116. Mouriri apiranga Spruce ex Triana | Apiranga | Mellitophily |

| Melastomataceae | 117. Mouriri eugeniifolia Spruce ex Triana | Dauicu | Mellitophily |

| Malastomataceae | 118. Mouriri ficoides Morley | Muriri | Mellitophily |

| Melastomataceae | 119. Mouriri grandiflora DC. | Camutim | Mellitophily |

| Melastomataceae | 120. Mouriri guianensis Aubl. | Gurguri | Phalenophily |

| Melastomataceae | 121. Mouriri pusa Gardner | Puçá | Mellitophily |

| Melastomataceae | 122. Mouriri trunciflora Ducke | Mirauba | Mellitophily |

| Polygalaceae | 123. Moutabea chodatiana Huber | Gogó-de-Guariba | Undefined |

| Musaceae | 124. Musa X paradisiaca L. | Banana | Chiropterophily |

| Myrtaceae | 125. Myrcia fallax (Rich.) DC. | Frutinheira | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 126. Myrciaria dubia (KUNTH) McVaugh | Caçari, camu-camuzeiro | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 127. Neoxythece elegans (A. DC) Aubr | Caramuri | Undefined |

| Arecaceae | 128. Oenocarpus bacaba Mart. | Bacaba | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 129. Oenocarpus bataua Mart. | Patauá | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 130. Oenocarpus mapora Karsten | Bacabinha | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 131. Oenocarpus minor Mart. | Bacabi | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 132. Oenorcapus distichus Mart. | Bacaba-de-Leque | Cantharophily |

| Arecaceae | 133. Orbignya phalerata Mart. | Babaçu | Undefined |

| Bombacaceae | 134. Pachira aquatica Aubl. | Mamorana | Chiropterophily |

| Apocynaceae | 135. Parahancornia amapa (Hub.) Ducke | Amapá | Phalenophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 136. Parinari montana Aubl. | Pajurá-da-Mata | Mellitophily |

| Crisobalanaceae | 137. Parinari sprucei Hook.f. | Uará | Mellitophily |

| Passifloraceae | 138. Passiflora edulis Sims f. flavicarpas Deg. | Maracujá | Mellitophily |

| Passifloraceae | 139. Passiflora nitida Kunth | Maracujá-Suspiro | Mellitophily |

| Passifloraceae | 140. Passiflora quadrangularis L. | Maracujá-Açu | Mellitophily |

| Sapindaceae | 141. Paullinia cupana H.B.K. var. sorbilis (Mart.) Ducke | Guaraná | Mellitophily |

| Hippocrateaceae | 142. Peritassa laevigata (Hoffm. Ex Link.) A. C. Smith | Gulosa | Mellitophily |

| Lauraceae | 143. Persea americana Mill. Var. americana Mill | Abacate | Mellitophily |

| Solanaceae | 144. Physalis angulata L. | Camapu | Myophily |

| Clusiaceae | 145. Platonia insignis Mart. | Bacuri | Ornithophily |

| Icacinaceae | 146. Poraqueiba paraensis Ducke | Umari ou Mari | Mellitophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 147. Poupartia amazonica Ducke | Jacaiacá | Undefined |

| Moraceae | 148. Pourouma cecropiifolia Mart. | Mapati | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 149. Pouteria caimito (Ruiz & Pavon) Radlk. | Abiu | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 150. Pouteria macrocarpa (Huber) Baenhi | Cutite-Grande | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 151. Pouteria macrophylla (Lam.) Eyma | Cutite | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 152. Pouteria pariry (Ducke) Baehni | Pariri | Undefined |

| Sapotaceae | 153. Pouteria ramiflora (Mart.) Radlk | Abiu-do-cerrado | Undefined |

| Sapotaceae | 154. Pouteria speciosa (Ducke) Baehni | Pajurá-de-Óbidos | Undefined |

| Sapotaceae | 155. Pouteria spp. | Abiurana | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 156. Pouteria torta (Mart.) Ralk | Abiu-Piloso | Mellitophily |

| Sapotaceae | 157. Pouteria ucuqui Pires & Schultes | Ucuqui | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 158. Psidium acutangulum DC. | Araçá-Pera | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 159. Psidium guajava L. | Goiaba | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 160. Psidium guineense Swartz | Araçá | Mellitophily |

| Bombacaceae | 161. Quararibea cordata (Bonpl.) Visch. | Sapota-do-Solimões | Mellitophily |

| Quiinaceae | 162. Quiina florida Tul. | Pama | Undefined |

| Clusiaceae | 163. Rheedia acuminata (Rui & Pav.) Planch. & Triana | Bacurizinho | Mellitophily |

| Clusiaceae | 164. Rheedia brasiliensis (Mart. Planch. & Triana | Bacuripari-Liso | Mellitophily |

| Clusiaceae | 165. Rheedia gardneriana Miers ex. Planch. & Triana | Bacuri mirim | Mellitophily |

| Clusiaceae | 166. Rheedia macrophylla (Mart.) Planch. & Triana | Bacuripari | Mellitophily |

| Annonaceae | 167. Rollinia mucosa (Jacq.) Baill. | Biribá | Cantharophily |

| Humiriaceae | 168. Sacoglottis guianensis Benth. | Achuá | Mellitophily |

| Hippocrateaceae | 169. Salacia impressifolia (Miers) A.C. Smith | Uaimiratipi | Undefined |

| Arecaceae | 170. Scheelea phalerata (Mart.) Burret | Acuri | Undefined |

| Solanaceae | 171. Solanum sessiliflorum Dunal. | Cubiu | Undefined |

| Anacardiaceae | 172. Spondias dulcis Park. | Cajarana | Mellitophily |

| Anacardiaceae | 173. Spondias mombin L. | Taperebá | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 174. Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | Ameixa | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 175. Syzygium malaccense (L.) Merr. & L. M. Perry | Jambo | Mellitophily |

| Myrtaceae | 176. Syzygium samarangense (Blume) Merr. & L.M. Perry | Jambo-Rosa | Mellitophily |

| Sapindaceae | 177. Talisia esculenta (A. St. Hil.) Radlk | Pitomba | Mellitophily |

| Leguminosae | 178. Tamarindus indica L. | Tamarindo | Mellitophily |

| Malvaceae | 179. Theobroma bicolor Humb. & Bonpl. | Cacacu-do-Peru | Mellitophily |

| Malvaceae | 180. Theobroma cacao L. | Cacau | Mellitophily |

| Malvaceae | 181. Theobroma canumanense Pires &Fróes ex Cuatrecasas | Cupuaçu-do-Mato | Mellitophily |

| Sterculiaceae | 182. Theobroma grandiflorum (Willd. Ex Spreng.) Schum | Cupuaçu | Cantharophily |

| Malvaceae | 183. Theobroma mariae (Mart.) Schum. | Cacau-Jacaré | Mellitophily |

| Malvaceae | 184. Theobroma obovatum Klotsch ex Bernoulli | Cabeça-de-Urubu | Mellitophily |

| Malvaceae | 185. Theobroma speciosum Willd. | Cacauí | Myophily |

| Malvaceae | 186. Theobroma subincanum Mart. | Cupuí | Mellitophily |

| Annonaceae | 187. Xylopia romatica (Lam.) Mart. | Pimenta-de-Macaco | Cantharophily |

| Rhamnaceae | 188. Zizyphus mauritiana Lam. | Dão | Mellitophily |

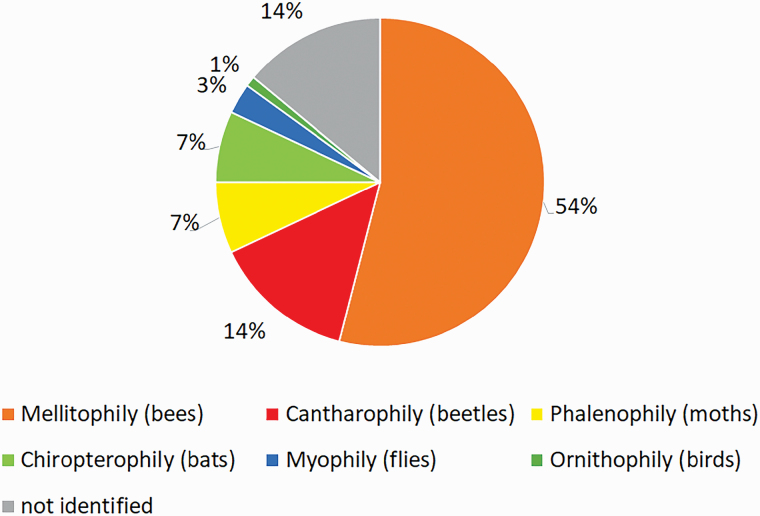

Plant species analyzed (161 species) were classified as having animal pollination syndromes, meaning that they do not exhibit characteristics of wind or water pollination (anemophily and hydrophily, respectively). Most of the studied plants (101 species; 54%) were classified as having a melittophily syndrome (characteristics related to the attraction of bees) (Fig. 1). The other most frequent syndromes were cantharophily (beetles), which was identified for 26 species (14%); chiropterophily (bats), which was identified for 14 species (7%); and phalenophily (moths), which was identified for 13 plant species (7%). These four syndromes represented 82% of all plants analyzed. Considering all insects quoted (bees, beetles, moths, and flies), the total percentage is equal to 78%. Additional information on the flowering period could not be obtained for 56 plant species. A short flowering period was found for 26 species (maximum 2 mo). The other species (106 species) had a flowering period of 3 mo or more (Supp Information 1 [online only]).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of pollination syndromes of 188 edible fruit plant species in the Amazon Tropical Forest.

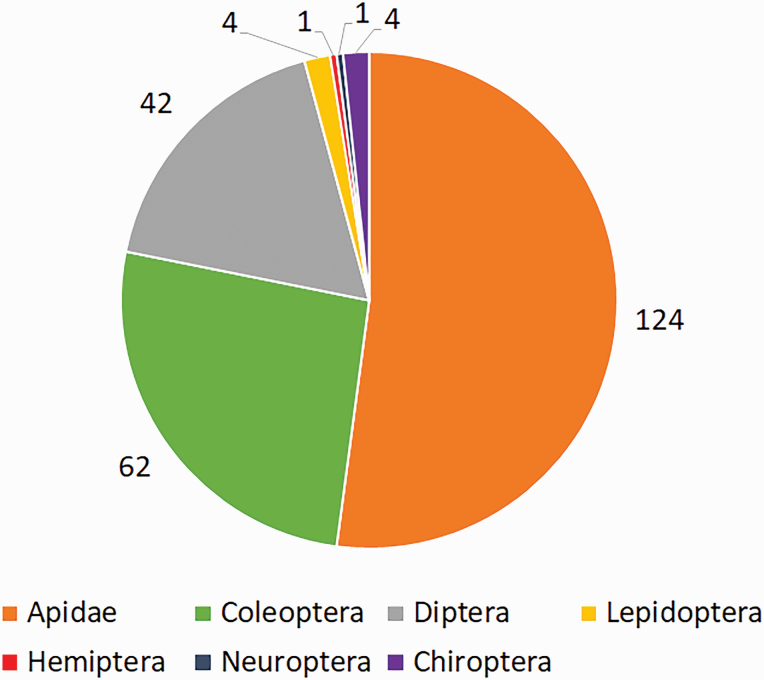

Studies conducted by other authors provided data on animal visitors or pollinators for 52 analyzed plant species, accounting for 28% of the total. These studies quoted 238 animal taxa (Supp Information 1 [online only]), of which 124 were bees of the Apidae family (58 Meliponini tribe; 20 species of Centris Fabricius, 1804 (Hymenoptera: Apidae)) (Table 3), 62 Coleoptera, 42 Diptera, four Lepidoptera, one Hemiptera, one Neuroptera and four Chiroptera (Fig. 2; Supp Information 1 [online only]). Honey bee (Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758) was highlighted as being associated to the largest number of plant species. Stingless bees belonging to the genera Trigona Jurine 1807 (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Partamona Schwarz 1939 (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Melipona Illiger 1806 (Hymenoptera: Apidae), and Trigonisca Moure 1950 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) were also emphasized as exhibiting the highest number of species quoted as pollinators. Trigona pallens (Fabricius, 1798) (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and T. fulviventris Guérin, 1844 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) are also noteworthy, exhibiting the highest number of interacting plant species (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Bee species previously quoted in the literature as pollinator/visitor of analyzed edible plant species in the Brazilian Amazon Forest (classification according to Moure et al. 2007) (complete information can be found in the Supp Information 1 [online only])

| Family | Tribe | Bee species | Brazilian vernacular name of plant species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apidae | Meliponini | 1. Aparatrigona impunctata (Ducke, 1916) | cupuaçu; açaí |

| Apidae | Apini | 2. Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758 | cauí; tucumã-do-pará; melão; araçá-boi; manga; caçari; abacate; araçá-pera; goiaba; taperebá; muruci; açai |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 3. Augochlora Smith, 1853 | açaí |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 4. Augochlorodes Moure, 1958 | açaí |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 5. Augochloropsis crassigena Moure, 1943 | muruci |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 6. Augochloropsis Cockerell, 1897 | açaí |

| Apidae | Bombini | 7. Bombus brevivilus Franklin 1913 | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Bombini | 8. Bombus transversalis (Olivier, 1789) | castanha-do-pará; urucum |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 9. Celetrigona longicornis (Friese, 1903) | açaí |

| Apidae | Centridini | 10. Centris sp Fabricius, 1804 | caju |

| Apidae | Centridini | 11. Centris aenea Lepeletier, 1841 | goiaba |

| Apidae | Centridini | 12. Centris americana Klug, 1810 | castanha-do-pará; acerola |

| Apidae | Centridini | 13. Centris bicolor Lepeletier, 1841 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 14. Centris byrsonimae Mahlmann & Oliveira sp. n | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 15. Centris carrikeri Cockerell, 1919 | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Centridini | 16. Centris caxienses (Ducke 1907) | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 17. Centris decolorata Lepeletier, 1841 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 18. Centris denudans Lepeletier, 1841 | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Centridini | 19. Centris ferruginea Lepeletier, 1841 | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Centridini | 20. Centris flavifrons Fabricius, 1775 | acerola; muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 21. Centris fuscata Lepeletier, 1841 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 22. Centris longimana Fabricius, 1804 | acerola; muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 23. Centris rhodoprocta Moure & Seabra, 1960 | acerola; muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 24. Centris similis Fabricius, 1804 | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Centridini | 25. Centris spilopoda Moure, 1969 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 26. Centris sponsa Smith, 1854 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 27. Centris tarsata Smith, 1874 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 28. Centris terminata Smith, 1874 | acerola |

| Apidae | Centridini | 29. Centris trigonoides Lepeletier, 1841 | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 30. Cephalotrigona capitata (Smith, 1854) | açai |

| Apidae | Xylocopini | 31. Ceratina Latreille, 1802 | açai |

| Apidae | Halictini | 32. Dialictus Robertson, 1902 | açai |

| Apidae | Anthidiini | 33. Dicranthidium arenarium (Ducke, 1907) | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 34. Dolichotrigona longitarsis (Ducke, 1916) | açai |

| Apidae | Centridini | 35. Epicharis affinis Smith, 1874 | castanha-do-pará; urucum |

| Apidae | Centridini | 36. Epicharis analis Lepeletier, 1841 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 37. Epicharis bicolor Smith, 1854 | muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 38. Epicharis conica Smith, 1874 | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Centridini | 39. Epicharis flava Friese, 1900 | castanha-do-pará; urucum; muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 40. Epicharis rustica Friese, 1900 | castanha-do-pará; urucum |

| Apidae | Centridini | 41. Epicharis umbraculata Friese, 1900 | castanha-do-pará; muruci |

| Apidae | Centridini | 42. Epicharis zonata Smith 1854 | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 43. Euglossini Latreille, 1802 | mangaba |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 44. Eulaema bombiformis (Packard, 1869) | araçá-pera |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 45. Eufriesea flaviventris (Friese, 1899) | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 46. Eufriesea purpurata (Mocsáry, 1896) | castanha-do-pará |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 47. Eulaema cingulata Moure, 1950 | castanha-do-pará; urucum |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 48. Eulaema meriana (Olivier, 1789) | castanha-do-pará; urucum |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 49. Eulaema mocsaryi (Friese, 1899) | castanha-do-pará; araçá-boi |

| Apidae | Euglossini | 50. Eulaema nigrita Lepeletier, 1841 | castanha-do-pará; cubiu |

| Apidae | Exomalopsini | 51. Exomalopsis Spinola, 1853 | açai |

| Apidae | Exomalopsini | 52. Exomalopsis auropilosa Spinola, 1853 | caçari |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 53. Frieseomelitta longipes (Smith, 1854) | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 54. Frieseomelitta portoi (Friese, 1900) | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 55. Geotrigona aequinoctialis (Ducke, 1925) | açai |

| Apidae | Halictini | 56. Habralictus Moure, 1941 | açai |

| Apidae | Hylaeini | 57. Hylaeus Fabricius, 1793 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 58. Leurotrigona pusilla Moure & Camargo, in Moure et al. 1988 | cupuaçu |

| Apidae | Tapinotaspidini | 59. Lophopedia pygmaea (Schrottky, 1902) | muruci |

| Apidae | Megachilini | 60. Megachile Latreille, 1802 | caju |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 61. Megalopta aeneicollis Friese, 1926 | guaraná |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 62. Megalopta amoena (Spinola, 1853) | guaraná |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 63. Megalopta sodalis (Vachal, 1904) | guaraná |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 64. Melipona brachychaeta Moure, 1950 | jambo |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 65. Melipona compressipes Smith, 1854 | caçari |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 66. Melipona fasciculata Smith, 1854 | urucum; caçari; taperebá |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 67. Melipona flavolineata Friese, 1900 | caçari; taperebá; açaí |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 68. Melipona melanoventer Schwarz, 1932 | urucum |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 69. Melipona paraenses Ducke, 1916 | acerola |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 70. Melipona seminigra Friese, 1903 | caçari; taperebá; jambo |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 71. Nannotrigona dutrae (Friese, 1901) | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 72. Nannotrigona punctata (Smith, 1854) | caçari; muruci; açaí |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 73. Nannotrigona schultzei (Friese, 1901) | açai |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 74. Neocorynura Schrottky, 1910 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 75. Oxytrigona ignis Camargo, 1984 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 76. Oxytrigona Cockerell, 1917 | açai |

| Apidae | Tapinotaspidini | 77. Paratetrapedia Moure, 1941 | açai |

| Apidae | Tapinotaspidini | 78. Paratetrapedia leucostoma (Cockerell, 1923) | muruci |

| Apidae | Tapinotaspidini | 79. Paratetrapedia testacea (Smith, 1854) | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 80. Paratrigona peltata (Spinola, 1853) | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 81. Partamona ailyae Camargo, 1980 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 82. Partamona cupira (Smith, 1863) | caçari |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 83. Partamona mourei Camargo, 1980 | jambo |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 84. Partamona pearsoni (Schwarz, 1938) | jambo; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 85. Partamona Schwarz, 1939 | caçari |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 86. Partamona testacea (Klug, 1807) | jambo; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 87. Partamona vicina Camargo, 1980 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 88. Pereirapis Moure 1943 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 89. Plebeia alvarengai Moure 1994 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 90. Plebeia fallax Hibbs | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 91. Plebeia minima (Gribodo, 1893) | Cupuaçu; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 92. Plebeia Schwarz, 1938 | açai |

| Apidae | Diphaglossini | 93. Ptiloglossa lucernarum Cockerell, 1923 | guaraná |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 94. Ptilotrigona lurida (Smith, 1854) | araçá-boi; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 95. Scaptotrigona postica (Latreille, 1807) | taperebá; muruci; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 96. Scaura latitarsis (Friese, 1900) | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 97. Scaura tenuis (Ducke, 1916) | açai |

| Apidae | Augochlorini | 98. Temnosoma Smith 1853 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 99. Tetragona beebei (Schwarz, 1938) | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 100. Tetragona clavipes (Fabricius, 1804) | acerola |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 101. Tetragonisca angustula (Latreille, 1811) | cupuaçu |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 102. Tetrapedia diversipes Klug, 1810 | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 103. Trigona amazonenses (Ducke, 1916) | jambo |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 104. Trigona branneri Cockerell, 1912 | caçari; jambo; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 105. Trigona dallatorreana Friese, 1900 | jambo |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 106. Trigona fulviventris Guérin, 1844 | cubiu; taperebá; cupuaçu; muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 107. Trigona fuscipennis Friese, 1900 | taperebá; muruci; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 108. Trigona guianae Cockerell, 1910 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 109. Trigona pallens (Fabricius, 1798) | cupuaçu; caçari; taperebá; muruci; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 110. Trigona recursa Smith, 1863 | caçari; açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 111. Trigona Jurine, 1807 | carambola |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 112. Trigona williana Friese, 1900 | jambo |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 113. Trigonisca dobzhanskyi (Moure, 1950) | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 114. Trigonisca extrema Albuquerque & Camargo, 2007 | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 115. Trigonisca hirticornis Albuquerque & Camargo, 2007 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 116. Trigonisca nataliae (Moure, 1950) | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 117. Trigonisca pediculana (Fabricius, 1804) | muruci |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 118. Trigonisca unidentata Albuquerque & Camargo, 2007 | açai |

| Apidae | Meliponini | 119. Trigonisca vitrifrons Albuquerque & Camargo, 2007 | açai |

| Apidae | Tapinotaspidini | 120. Tropidopedia punctifrons (Smith, 1879) | muruci |

| Apidae | Tapinotaspidini | 121. Xanthopedia globulosa (Friese, 1899) | muruci |

| Apidae | Xylocopini | 122. Xylocopa aurulenta (Fabricius, 1804) | urucum |

| Apidae | Xylocopini | 123. Xylocopa frontalis Olivier, 1789 | castanha-do-pará; urucum |

| Apidae | Xylocopini | 124. Xylocopa Latreille, 1802 | goiaba |

Fig. 2.

Number of taxa cited in previous works about pollinator/visitor in 52 of the analyzed edible fruit plant species in the Amazon Tropical Forest. Taxa of Apidae family are quoted on Table 3. All taxa can be found in the Supp Information 1 (online only).

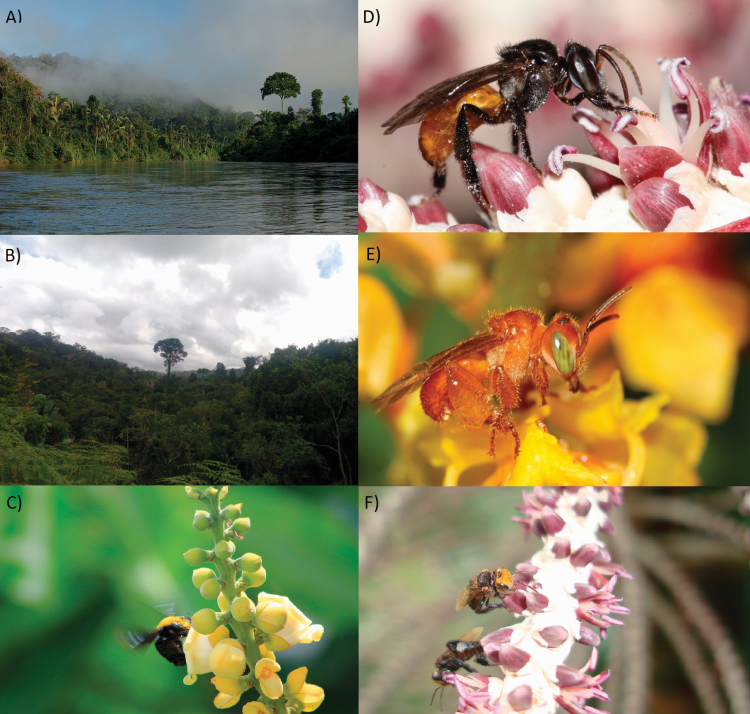

Fig. 3.

(A and B) Aspects of the Amazon Forest with the striking view of Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa) with its high stature and straight trunk (Photos: João Rosa and Rafael M. Brito, respectively); (C) Carpenter bee (Xylocopa frontalis Olivier, 1789 (Hymenoptera: Apidae)) on Brazil nut blossom (Photo: Marcia M. Maués); (D) Trigona fulviventris (male) on muruci (Byrsonima crassifolia) flower (Photo: Cristiano Menezes); (E) Trigona palllens (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on açaí (Euterpe oleracea) inflorescence (Photo: Cristiano Menezes); and (F) Oxytrigona sp. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on açaí (Euterpe oleracea) inflorescence (Photo: Alistair J. Campbell).

Discussion

Results obtained through pollination syndrome showed that half of all edible fruit plant species analyzed exhibit melittophily syndrome, indicating the importance of bees. Our data also showed that all the different insect groups determined by pollination syndrome are responsible for pollinating more than two-third of all plant species analyzed. Through the literature review, bee and beetle species were also particularly emphasized.

As already stated, bees are widely considered as important crop pollinators, especially highly social bees (Slaa et al. 2006, Giannini et al. 2020a). Traditional communities and indigenous people also acknowledge the importance of bees (Potts et al. 2016). In the Amazon, the importance of bees for indigenous people was documented among Kayapó tribe (Posey 1985, Posey and Camargo 1985), and other indigenous people (Athayde et al. 2016), mainly for honey and wax hunting and beekeeping practices. Bee diversity is also recognized by them as representing a key aspect (Athayde et al. 2016).

Native bees are especially important to pollination and they are considered as being more efficient for crop pollination than exotic species, such as the honey bee (Garibaldi et al. 2013). Competition between native bees and honey bees was demonstrated in forests of Mexico (Roubik and Villanueva-Gutierrez 2009). However, there is no study about competition conducted within Amazon forests, and we still have scarce data about the role of honey bees in this biome. Previous studies showed that honey bees are more prevalent on deforested areas than inside the closed forests of south-western Amazon (Brown et al. 2016). Nevertheless, they were reported as an important alternative pollinator on deforested lands (Dick et al. 2003, Ricketts 2004). The Amazon harbor a rich diversity of native stingless bees (ca. 190 species, Pedro 2014). These bees present a wide diet breadth (Ramalho 2004, Lichtenberg et al. 2017) and are considered as key pollinators of forests (Bawa 1990). For Brazil, other bee species are also recognized as important effective pollinators, as the solitary bee species Centris Fabricius, 1804 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and Xylocopa Latreille, 1802 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and the primitively eusocial Bombus Latreille, 1802 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) (Giannini et al. 2020a). Important non-bee insects reported as crop pollinators in Brazil were beetles (Curculionidae and Chrysomelidae) and flies (Syrphidae) (Giannini et al. 2015a), playing a significant role as crop pollinators globally and providing potential insurance against bee decline (Rader et al. 2016).

Among the Amazon plant species that depend on bees, Bertholletia excelsa HBK (Cavalcante et al. 2018), which is popularly known as the Brazil nut tree, is noteworthy, because its nuts present high nutritional and economic value (Kainer et al. 2018). Bee pollinators include two species of primitively social Bombus Latreille, 1802 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and 18 species of solitary bees. Another native species with high economic value is passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims f. flavicarpa Deg), mainly pollinated by larger solitary bees such as Xylocopa Latreille, 1802 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) (Yamamoto et al. 2012); however, no study was found about passion fruit pollination in the Amazon forest. This species is cultivated in all states of Brazil, with a total production of more than 550,000 tons (2017 data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics - IBGE), and it is highly dependent on pollination to produce its fruits; thus, in the absence of pollinators, production does not occur (Yamamoto et al. 2012).

The second most important pollinator group were beetles, with plants displaying specific adaptations for beetle pollination classified as cantharophilous. This pollination syndrome was primarily associated with Amazon palm species, such as the inajá (Maximiliana maripa (Aubl.) Drude) and bacaba (Oenocarpus bacaba Mart.). Beetles reported here included Cyclocephala distincta Burmeister, 1847 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae); Belopeus carmelitus (Germar, 1824) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae); and species of Epitragini tribe. The beetles that pollinate these species of palm trees are attracted by the floral scents produced by thermogenesis of the inflorescences (Oliveira et al. 2003), and such an interaction has been previously documented in other species, as those belonging to the Araceae family (Gottsberger 1990; Maia et al. 2010, 2013). Beetles of both sexes are attracted by the fragrance of flowers, which they use as a mating site, thus enabling pollination (Gottsberger 1986, Bernhardt 2000).

Despite providing an important indication of the main pollinators for each plant species, especially for megadiverse habitats, the pollination syndrome concept has received criticism, mainly because many plants can be pollinated by different pollinators, and it has been suggested that results should be better understood as working hypotheses (Quintero et al. 2017). Two cases here are noteworthy since the analyzed plants exhibit a complex pollination syndrome. One of them is açaí palm (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) that was classified here as predominately pollinated by beetles. However, a recent study determined over 100 species acting as pollinators, including, besides beetles, bees, flies, wasps, and ants (Campbell et al. 2018). Another example is cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) that was considered here as being mainly pollinated by bees, but also presents a complex pollination system recently reviewed (Toledo-Hernández et al. 2017). For this last species, no study was conducted in the Amazon forest for determining its main pollinators. Both crops (açaí and cocoa) presented the highest value of crop pollination service in Pará (Borges et al. 2020), being also dependent on pollinators (Toledo-Hernández et al. 2017, Campbell et al. 2018). Thus, complex pollination systems require caution when being analyzed through pollination syndromes. Future work could emphasize priority edible plant species to be analyzed through detailed fieldwork, cocoa being one of the main priorities.

Protecting local animal diversity is of extreme importance for fruit production, especially in forested habitats. Increasing the knowledge about insects is also a key factor, especially considering their high diversity in tropical habitats and the historical disregarding of their ecological importance. Habitat heterogeneity is key since more heterogeneous environments can support more species through niche partitioning (Tilman 1982, Chesson 2000, Tscharntke et al. 2012, Moreira et al. 2015), and a higher pollinator diversity can directly affect the reproduction of cultivated and wild plants by increasing pollen transfer and fruit and seed production (Kremen et al. 2002, Klein et al. 2003, Hoehn et al. 2008, Garibaldi et al. 2013). Restoration of degraded land programs, especially on the region of Amazon Arc of Deforestation (south and eastern Amazon), can also benefit from a rich diversity of native plant species, and the list provided here is particularly useful for agroforestry projects aiming to associate restoration with sustainable development (Garrity 2004).

We conclude that the Amazon plant species that produce edible fruits are pollinated mainly by bees, especially stingless bees, but other insects are also important, such as beetles and moths. Animal pollinators underpin food security in traditional communities in the Amazon forest and should be protected. There are still few studies on the reproductive biology of edible plant species, and this knowledge is essential for understanding the level of dependence of plants on their pollinators and for helping on decision-making processes for pollinator protection and sustainability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Pará Research Foundation (FAPESPA/ICAAF 019/2016 and 014/2017) and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq 300464/2016-9). We thank Marcia M. Maués, Alistair John Campbell, and Rafael Cabral Borges for providing suggestions on the manuscript. We also thank Alistair John Campbell, Cristiano Menezes, João Rosa, Marcia M. Maués and Maria de Lourdes Giannini for the photos provided.

References Cited

- Athayde, S., Stepp J. R., and Ballester W. C.. 2016. Engaging indigenous and academic knowledge on bees in the Amazon: implications for environmental management and transdisciplinary research. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 12: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawa, K. S. 1990. Plant-pollinator interactions in tropical rain forests. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 21: 399–422. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, P. 2000. Convergent evolution and adaptive radiation of beetle pollinated angiosperms. Plant Sys. Evol. 222: 293–320. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, R. C., Brito R. M., Imperatriz-Fonseca V. L., and Giannini T. C.. 2020. The Value of crop production and pollination services in the eastern Amazon. Neotrop. Entomol. 49: 545–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. C., Mayes D., and Bhatta C.. 2016. Observations of Africanized honey bee Apis mellifera scutellata absence and presence within and outside forests across Rondonia, Brazil. Insectes Soc. 63: 603–607. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann, S. L., and Nabhan G. P.. 1997. The Forgotten Pollinators. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A. J., Carvalheiro L. G., Maués M. M., Jaffé R., Giannini T. C., Freitas M. A. B., Coelho B. W. T., and Menezes C.. 2018. Anthropogenic disturbance of tropical forests threatens pollination services to açaí palm in the Amazon river delta. J. Appl. Ecol. 55: 1725–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, P. B. 1996. Frutas comestíveis da Amazônia. MPEG, Belém, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, M. C., Galetto L., Maués M. M., Pacheco A. J. S., and Bomfim I. G. A.. 2018. Nectar production dynamics and daily pattern of pollinator visits in Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl.) plantations in Central Amazon: implications for fruit production. Apidologie 49: 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Chesson, P. 2000. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 31: 343–366. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, C. R., Müller C. H., and Flores W. B. C.. 1982. Recursos genéticos de espécies frutíferas nativas da Amazônia Brasileira. Acta Amazonica 12: 677–695. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Flores, J., Hernández-Esquivel K. B., González-Rodríguez A., and Ibarra-Manríquez G.. 2017. Flowering phenology, growth forms, and pollination syndromes in tropical dry forest species: influence of phylogeny and abiotic factors. Am. J. Bot. 104: 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R., d’Arge R., de Groot R., Farber S., Grasso M., Hannon B., Limburg K., Naeem S., O’Neill R. V., Paruelo J., . et al. 1997. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387: 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R., Groot R., Sutton P., van der Ploeg S., Anderson S. J., Kubiszewiski I., Farber S., and Turner R. K.. 2014. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environ. Change 26: 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard B., Gonzalez A. M. M., Olesen J. M., Timmermann A., Andersen L. H., and Ollerton J.. 2008. Pollination networks and functional specialization: a test using Lesser Antillean plant-hummingbird assemblages. Oikos 117: 789–793. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, S., Pascual U., Stenseke M., Martín-López B., Watson R. T., Molnár Z., Hill R., Chan K. M. A., Baste I. A., Brauman K. A., . et al. 2018. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science. 359: 270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick, C. W., Etchelecu G., and Austerlitz F.. 2003. Pollen dispersal of tropical trees (Dinizia excelsa: Fabaceae) by native insects and African honeybees in pristine and fragmented Amazonian rainforest. Mol. Ecol. 12: 753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faegri, K., and van der Pijl L.. 1979. The principles of pollination ecology. Pergamon Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Fenster, C. B., Armbruster W. S., Wilson P., Dudash M. R., and Thomsom J. D.. 2004. Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35: 375–403. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, L. A., Steffan-Dewenter I., Winfree R., Aizen M. A., Bommarco R., Cunningham S. A., Kremen C., Carvalheiro L. G., Harder L. D., Afik O., . et al. 2013. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science. 339: 1608–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, L. A., Carvalheiro L. G., Vaissière B. E., Gemmill-Herren B., Hipólito J., Freitas B. M., Ngo H. T., Azzu N., Sáez A., Åström J., . et al. 2016. Mutually beneficial pollinator diversity and crop yield outcomes in small and large farms. Science. 351: 388–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity, D. P. 2004. Agroforestry and the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. Agroforest Syst. 61: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Giacometti, D. C. 1993. Recursos genéticos de fruteiras nativas do Brasil, pp. 13-27. InSIMPOSIO NACIONAL DE RECURSOS GENETICOS DE FRUTEIRAS NATIVAS, Cruz das Almas, BA. Anais. Cruz das Almas, BA: EMBRAPA-CNPMF, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T. C., Boff S., Cordeiro G. D., Cartolano E. A. Jr., Veiga A. K., Imperatriz-Fonseca V. L., and Saraiva A. M.. 2015a. Crop pollinators in Brazil: a review of reported interactions. Apidologie 46: 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T. C., Cordeiro G. D., Freitas B. M., Saraiva A. M., and Imperatriz-Fonseca V. L.. 2015b. The dependence of crops for pollinators and the economic value of pollination in Brazil. J. Econ. Entomol. 108: 849–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T. C., Costa W. F., Cordeiro G. D., Imperatriz-Fonseca V. L., Saraiva A. M., Biesmeijer J., and Garibaldi L. A.. 2017. Projected climate change threatens pollinators and crop production in Brazil. PLoS One 12: e0182274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T. C., Alves D. A., Alves R., Cordeiro G. D., Campbell A. J., Awade M., Bento J. M. S., Saraiva A. M., and Imperatriz-Fonseca V. L.. 2020a. Unveiling the contribution of bee pollinators to Brazilian crops with implications for bee management. Apidologie 51: 406–421. doi: 10.1007/s13592-019-00727-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T. C., Costa W. F., Borges R. C., Miranda L., Costa C. P. W., Saraiva A. M., and Imperatriz-Fonseca V. L.. 2020b. Climate change in the Eastern Amazon: crop-pollinator and occurrence-restricted bees are potentially more affected. Reg. Environ. Change 20: 9. doi: 10.1007/s10113-020-01611-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Girão, L. C., Lopes A. V., Tabarelli M., and Bruna E. M.. 2007. Changes in tree reproductive traits reduce functional diversity in a fragmented Atlantic forest landscape. PLoS One 2: e908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, V. H. F., Vieira I. C. G., Salomão R. P., Steege H.. 2019. Amazonian tree species threatened by deforestation and climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9: 547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Gottsberger, G. 1986. Some pollination strategies in neotropical savannas and forests. Plant Sys. Evol. 152: 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gottsberger, G. 1990. Flowers and beetles in the South American tropics. Botanica Acta 103: 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hill R, Nates-Parra G., Quezada-Euán J. J. G., Buchori D., LeBuhn G., Maués M. M., Pert P. L., Kwapong P. K., Saeed S., Breslow S. J., . et al. 2019. Biocultural approaches to pollinator conservation. Nat. Sustainability 2: 214–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn, P., Tscharntke T., Tylianakis J. M., and Steffan-Dewenter I.. 2008. Functional group diversity of bee pollinators increases crop yield. Proc. Biol. Sci. 275: 2283–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPBES . 2016. Summary for policymakers of the assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on pollinators pollination and food production. IPBES, Bonn, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. D., and Wester P.. 2017. Stefan Vogel’s analysis of floral syndromes in the South African flora: an appraisal based on 60 years of pollination studies. Flora 232: 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kainer, K. A., Wadt L. H. O., and Staudhammer C. L.. 2018. The evolving role of Bertholletia excelsa in Amazonia: contributing to local livelihoods and forest conservation. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 48: 477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, L. S., Torres R. B., Forni-Martins E. R., Spinelli T., Ahn Y. J., and Constância S. S.. 2006. Composição florística e síndromes de polinização e de dispersão da mata do Sítio São Francisco Campinas SP Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 20: 313–327. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A. M., Steffan-Dewenter I., and Tscharntke T.. 2003. Fruit set of highland coffee increases with the diversity of pollinating bees. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270: 955–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A. M., Vaissière B. E., Cane J. H., Steffan-Dewenter I., Cunningham S. A., Kremen C., and Tscharntke T.. 2007. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274: 303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen, C., Williams N. M., and Thorp R. W.. 2002. Crop pollination from native bees at risk from agricultural intensification. PNAS 26: 16813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg, E. M., Mendenhall C. D., and Brosi B.. 2017. Foraging traits modulate stingless bee community disassembly under forest loss. J. Anim. Ecol. 86: 1404–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado, I. C., and Lopes A. V.. 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian tropical dry forest. Ann. Bot. 94: 365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado, I. C., and Lopes A. V.. 2008. Recursos Florais e sistemas de polinização e sexuais em caatinga. InLeal I. R., Tabarelli M., and Silva J. M. C. (eds.), Ecologia e Conservação da Caatinga. UFPE. Recife, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, A. C. D., Schlindwein C., Navarro D. M. A. F., and Gibernau M.. 2010. Pollination of Philodendron acutatum (Araceae) in the Atlantic Forest of northeastern Brazil: a single scarab beetle species guarantees high fruit set. Int. J. Plant Sci. 171: 740–748. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, A. C. D., Gibernau M., Carvalho A. T., Gonçalves E. G., and Schlindwein C.. 2013. The cowl does not make the monk: scarab beetle pollination of the Neotropical aroid Taccarum ulei (Araceae Spathicarpeae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 108: 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, R., and Antonini Y.. 2016. Can pollination syndromes indicate ecological restoration success in tropical forests? Restor. Ecol. 24: 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, A., Dunn R. R., Fox R., Jongejans E., Leather S. R., Saunders M. E., Shortall C. R., Tingley M. W., and Wagner D. L.. 2020. Is the insect apocalypse upon us? How to find out. Biol. Conserv. 241: 108327. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, E. F., Boscolo D., and Viana B. F.. 2015. Spatial heterogeneity regulates plant-pollinator networks across multiple landscape scales. PLoS One 10: e0123628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moure, J. S., Urban D., and Melo G. A. R.. 2007. Catalogue of Bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) in the Neotropical Region. Curitiba, Sociedade Brasileira de Entomologia. 1058p. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, C. A., Sampaio G., Borma L. S., Castilla-Rubio J. C., Silva J. S., and Cardoso M.. 2016. Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: 10759–10768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M. S. P. D., Couturier G., and Beserra P.. 2003. Biologia da polinização da palmeira tucumã (Astrocaryum vulgare Mart.) em Belém. Acta Botanica Brasilica 17:343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ollerton, J., Winfree R., and Tarrant S.. 2011. How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos 120: 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, P. F. P. R., Ruivo M. L. P., Silva O. M. Jr, Maciel M. N. M., Braga T. G. M., Andrade M. M. N., Santos P. C. Jr, Rocha E. S., Freitas T. P. M., Leite T. V. S., . et al. (2020) Deforestation in protect areas in the Amazon: a threat to biodiversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 29: 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro, S. R. M. 2014. The stingless bee fauna in Brazil (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Sociobiology 61: 348–354. [Google Scholar]

- Pinton, F., and Emperaire L.. 2004. Agrobiodiversidade e agricultura tradicional na Amazônia: que perspectiva?, pp. 73–100. InSayago D., Tourand J. F. and Bursztin M. (orgs.). Amazônia: cenas e cenários. UnB. Brasília. [Google Scholar]

- Posey, D. A. 1985. Indigenous management of tropical forest ecosystems: the case of the Kayapó indians of the Brazilian Amazon. Agroforest Syst. 3: 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Posey, D. A., and Camargo J. M. F.. 1985. Additional notes in the classification and knowledge of stingless bees (Meliponinae, Apidae, Hymenoptera) by the Kayapo Indians of Gorotire (Pará, Brazil). Annals of the Carnegie Museum 54: 247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, S. G., Biesmeijer J. C., Kremen C., Neumann P., Schweiger O., and Kunin W. E.. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25: 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts, S. G., Imperatriz-Fonseca V., Ngo H. T., Aizen M. A., Biesmeijer J. C., Breeze T. D., Dicks L. V., Garibaldi L. A., Hill R., Settele J., . et al. 2016. Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature. 540: 220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, M., Yeo P., and Lack A.. 1996. The natural history of pollination. Harper Collins, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, E., Genzoni E., Mann N., Nuttman C., and Anderson B.. 2017. Sunbird surprise: a test of the predictive power of the syndrome concept. Flora 232: 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rader, R., Bartomeus I., Garibaldi L. A., Garratt M. P., Howlett B. G., Winfree R., Cunningham S. A., Mayfield M. M., Arthur A. D., Andersson G. K., . et al. 2016. Non-bee insects are important contributors to global crop pollination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, M. 2004. Stingless bees and mass flowering trees in the canopy of Atlantic Forest: a tight relationship. Acta Botanica Brasilica 18: 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts, T. H. 2004. Tropical forest fragments enhance pollinator activity in nearby coffee crops. Conserv. Biol. 18: 1262–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Guerrero, V., Aguilar R., Martén-Rodríguez S., Ashworth L., Lopezaraiza-Mikel M., Bastida J. M., and Quesada M.. 2014. A quantitative review of pollination syndromes: do floral traits predict effective pollinators? Ecol. Lett. 17: 388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubik, D. W., and Villanueva-Gutierrez R.. 2009. Invasive Africanized honey bee impact on native solitary bees: a pollen resource and trap nest analysis. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 98: 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S. 2011. Frutas da Amazônia Brasileira. Metalivros, São Paulo, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Slaa, E. J., Chaves L. A. S., and Malagodi-Braga K. S.. 2006. Stingless bees in applied pollination: practice and perspectives. Apidologie 37: 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Stang, M., Klinkhamer P. G. L., and Van Der Meijden E.. 2006. Size constraints and flower abundance determine the number of interactions in a plant-flower visitor web. Oikos 112: 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D. 1982. Resource competition and community structure. Princeton University Press, NJ, USA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Hernández, M., Wanger T. C., and Tscharntke T.. 2017. Neglected pollinators: can enhanced pollination services improve cocoa yields? A review. Agriculture Ecosystem and Environonment 247: 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tscharntke, T., Tylianakis J. M., Rand T. A., Didham R. K., Fahrig L., Batary P., Fründ J., Holt R. D., Holzschuh A., Klein A. M., . et al. 2012. Landscape moderation of biodiversity patterns and processes—eight hypotheses. Biol. Rev. 87: 661–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waser, N. W., Chittka L., Price M. V., Williams N. M., and Ollerton J.. 1996. Generalization in pollination systems, and why it matters. Ecology 77: 1043–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, M., Silva C. I., Augusto S. C., Barbosa A. A. A., and Oliveira P. E.. 2012. The role of bee diversity in pollination and fruit set of yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis forma flavicarpa Passifloraceae) crop in Central Brazil. Apidologie 43: 515–526. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.