Abstract

More research is needed that elucidates the mechanisms by which critical consciousness impacts marginalized youth’s academic and career development. To address this gap, this short-term longitudinal study (i.e., two waves) examined motivations for post-high school plans (i.e., career/personal motivation; humanitarian motivation; encouragement received from important individuals; pressure from parents/family to succeed) as mediators in the relationship between dimension of critical consciousness and academic and career activities. The sample consisted of low-income, Black and Latinx youth (N = 191; Mage = 16, SD = 0.80; 59% female) living in Chicago. The results from structural equation path models show that youth’s beliefs about their ability to engage politically (i.e., sociopolitical efficacy) predict motivations for post-secondary plans (e.g., encouragement; pressure from parents/family), which is subsequently related to engagement in academic and career activities, albeit in different directions. To continue fostering positive youth development, critical consciousness programming will need to integrate how youth understand their role in changing social inequality in relation to their perception of and interactions with parents and mentors.

Keywords: Critical consciousness, Post-secondary plans, Black and Latinx youth, Academic and career activities, Motivations

Introduction

Youth academic and career development, including engaging in academic and career activities, is a sign of thriving in adolescence and positive youth development (Blustein et al. 2005). For low-income, Black and Latinx youth academic and career development must be interpreted within the social-structural conditions that limit access to academic and career development opportunities (Spencer and Swanson 2013). Low academic standards and limited social capital may dampen youth’s academic aspirations (Alonso et al. 2009) and substantially limit actionable steps towards post high school plans (e.g., college, vocational training; Farmer-Hinton 2002). Despite the barriers faced by adolescents of color, previous empirical research suggests that critical consciousness, defined as an understanding of structural inequality (e.g., perceived inequality), perceived ability to engage politically (e.g., sociopolitical efficacy), and direct actions taken to enact social change (e.g., critical action), can be powerful forces in youth’s academic and career development (Diemer and Blustein 2006). Indeed, among youth of color critical consciousness is positively associated with academic achievement (Seider et al. 2020), career exploration (Diemer 2009), and adult occupational attainment (Rapa et al. 2018). However, very few studies have investigated how components of critical consciousness are related to youth’s preparation for post high school plans (i.e., engagement in academic and career activities while in high school). Moreover, more research is needed that elucidates the mechanisms by which critical consciousness impacts academic and career development (Heberle et al. 2020). To fill this gap in the literature, and support the development of adolescent programming, this study examines low-income, Black and Latinx youth’s motivations for post-secondary plans (i.e., career/personal motivation; humanitarian motivation; encouragement received from important individuals; and pressure from parents/family to succeed) as mediators in the relation between components of critical consciousness and teens academic and career activities.

Academic and Career Activities among Youth of Color

Late adolescence and emerging adulthood have been noted as critical stages where individuals begin to make choices and engage in a variety of activities that are influential on the rest of their lives (Zarrett and Eccles 2006). As youth move into emerging adulthood their choices and challenges shift to include decisions about education or vocational training, entry into and transitions within the labor market, joining the military, moving out of the family home, and sometimes marriage and parenthood. Youth nearing the end of high school engage in planning one’s future by taking the necessary steps to pursue those plans. Youth academic and career preparation has been measured in a variety of ways including work salience and vocational expectations (Diemer et al. 2010), commitment to careers (Arnold 2017), and engagement in academic and career activities (Perry et al. 2010). Theories on youth career development suggests that career planning via engagement in academic and career activities is a result of self-reflection and self-regulation (Lent et al. 2000). As teens explore their career interests, educational pathways may become a causal mechanism for their goals (Marciniak et al. 2020). These connections between school and work may help adolescents seek out and participate in activities that will help them prepare for and achieve their future goals (e.g., enrolling in particular training program or learning about a subject related to career interest; Lapan 2004).

Advances in career development models posit that youth engagement in academic and career activities is influenced by individual and contextual factors (Lent et al. 2002). Specifically, background characteristics and learning experiences may serve as precursors to academic and career preparatory behavior. In the current study, dimensions of critical consciousness (e.g., perceived inequality, sociopolitical efficacy, critical action) are conceptualized as factors that contribute to youth engagement in academic and career activities. Furthermore, individual and contextual factors facilitate academic and career interests and choice behavior (Lent et al. 2002). Whereas individual factors relate to personal interests, values, and perceived capabilities, contextual factors refer to perceived and actual availability of resources and competing demands (Lent et al. 2000). In the current study, motivation for pursuing specific academic and career paths after high school are analyzed as factors that contribute to youth engagement in academic and career activities. These motivations are conceptualized as individually driven (i.e., career/personal motivation; humanitarian motivation) and contextually driven (i.e., encouragement from others; expectation from family). Furthermore, it has been proposed that precursors variables (e.g., critical consciousness) also impact youth perception of individual and contextual factors (e.g., motivations), which subsequently impact academic and career choice action.

Critical Consciousness among Youth of Color

Critical consciousness describes the process by which oppressed and marginalized people learn to critically analyze their social conditions and act to improve them (Diemer 2020). Critical consciousness consists of three components: critical reflection, political efficacy, and critical action (Rapa and Geldhof 2020). Critical reflection involves the recognition of, and rejection of societal inequities. This dimension is further conceptualized as perceived inequality, which refers to the critical examination of social inequities specific to ethnic-racial, gendered, and socioeconomic limitations on educational and occupational opportunities (Diemer and Rapa 2016). As young people begin to critique decades of unjust social conditions and understand the mechanisms and manifestations of systemic inequities, they may start to unlearn negative social stereotypes of themselves (Shin et al. 2010) and understand the political system (Watts and Flanagan 2007). Theories on behavior and human motivation suggest that agency is a precursor to behavior: unless people believe they can produce a desired effect by their actions, they have little incentive to act or persevere in the face of challenges (Bandura 2000). In the context of critical consciousness, political efficacy refers to an individual’s perceived ability to transform their environmental circumstances and affect sociopolitical change. Critical action refers to individual or collective action within traditional forms of political engagement (e.g., voting, community organizing) and non-traditional forms of political engagement (e.g., protesting, posting on social media about a social or political issue) with the intention of changing unjust social conditions and policies (Diemer and Rapa 2016).

Critical consciousness holds the promise of helping marginalized youth navigate the pervasive stressors associated with their academic and vocational contexts and perceive higher levels of agency (Diemer and Blustein 2006). The conceptual underpinnings of critical reflection suggest that when adolescents engage and critique severe social injustices, the very structures that limit their development, adolescents are then able to “clear intellectual and emotional space” for academic and career goal exploration (Cammarota 2007, p. 95). However, a more nuanced examination into youth’s lived experiences reveals that an awareness of social injustices may not always lead to critical action (Lardier et al. 2019) and may be associated with hopelessness (Christens et al. 2018) among youth of color living in low-resource communities. Extant critical consciousness theory suggests that sociopolitical efficacy may protect youth from immobilization and negative consequences (Watts et al. 2011). Indeed, a recent study found that social political efficacy and critical action allowed marginalized youth to critically reflect on societal inequalities without repercussion on their mental health or engagement in school (Godfrey et al. 2019).

Opportunities for sociopolitical engagement for marginalized youth may be constrained by limited opportunities and the effects of cumulative disadvantage (Flanagan and Levine 2010). To this point, emerging research among Black and Latinx young adults suggests that sociopolitical engagement includes educational persistence and occupational attainment as forms of resistance to oppression (Lardier et al. 2019). For example, a qualitative study found that Latinx youth considered thriving, educational attainment, and cultural pride as forms of sociopolitical engagement (McWhirter et al. 2019). Moreover, conceptual (Solórzano and Bernal 2001) and empirical (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2015) studies suggest that civic occupations (i.e., careers that involve social services) are credible forms of political action.

Critical Consciousness and Career Development

A myriad of studies among urban youth of color find that critical consciousness is positively associated with career development outcomes such as career expectations (Diemer and Hsieh 2008), work salience (Diemer et al. 2010), and vocational identity and commitment (Diemer and Blustein 2006). Using a subset sample of low-income youth of color from the National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS), Diemer and Hsieh (2008) found that greater importance in helping one’s community and discussing current events with parents were associated with greater career expectations, a variable that took into account youth’s type of career they expect to obtain in the future and the level of education needed to attain that career. One other study found that sense of sociopolitical efficacy was associated with salience of work role and connection to future career, while critical reflection was related to vocational identity in a sample of urban youth (Diemer and Blustein 2006).

Importantly, longitudinal studies show that critical consciousness in high school may promote the attainment of higher-status occupations in adulthood. For example, in sample of predominantly Black youth from Maryland, critical action mediated the relationship between career expectations in high school and occupational attainment in adulthood (Rapa et al. 2018). Using the NELS, statistical analyses revealed that greater 10th-grade critical consciousness (items captured social responsibility and sociopolitical action) had a positive longitudinal impact on adult occupational attainment eight years later via 12th-grade critical consciousness (Diemer 2009). It may be that critical consciousness empowers marginalized youth to more effectively negotiate structural constraints and social identity threats as they transition into early adulthood, fostering participation in immediate (school) and long-term (career) pathways to social mobility (Rapa et al. 2018).

Critical Consciousness and Academic Development

Studies find critical consciousness is associated with higher levels of academic achievement and persistence among students of color. Critical consciousness about racism can motivate Black students to resist oppressive forces by persisting in school and achieving in academics (Carter 2008). Studies that examine the effect of critical consciousness on youth’s objective measures of academic achievement find that higher reports of critical reflection and critical action are related to lower school behavior problems among ethnically diverse high-school students (Luginbuhl et al. 2016). Similarly, one other study found that critical reflection and critical action, but not sociopolitical efficacy, were associated with higher grade point averages and college entrance exams scores (Seider et al. 2020). In an extension of this work, one study found that political outcome expectations, as a component of critical consciousness, were a positive predictor of higher intent to persist in college (Cadenas et al. 2018). Furthermore, studies find that school-based civic programs can foster youth’s feelings of political agency (Kozan et al. 2017) and commitment to action (Cabrera et al. 2014). It seems having a greater understanding of inequality and engagement in social action helps marginalized adolescents conceptualize their educational development as a method to promote social change and challenge oppressive forces within their social contexts (Ginwright and Cammarota 2002).

A few studies have examined how critical consciousness is related to academic engagement among youth of color, particularly related to post-high school planning. For example, one study found that Latinx youth who endorsed higher levels of critical consciousness also had greater engagement (e.g., academic, extracurricular, Spanish language, and helping) than those with low levels of critical consciousness (McWhirter and McWhirter 2016). Although academic activities were not directly measured in the context of marginalization and oppression, this study suggests that critical consciousness may be a catalyst for adolescents’ post-secondary school plans via engagement during high school. Indeed, a related study on Latinx students found that adolescents’ critical awareness of inequity directly predicated their reasons for attending school (i.e., academic motivation), which subsequently positively predicted educational aspirations and vocational goals (Luginbuhl et al. 2016). That is, adolescents with greater critical consciousness saw education as an avenue through which to transform structural barriers. Considering these studies, youths engagement in their future plans via academic and career activities may indicate their evolving level of agency, such that as students became more aware of injustice and more motivated to produce social change, they also develop more capacity for engaging in academic and career preparatory behaviors.

Motivations for Post-Secondary Plans and Academic and Career Activities

Research in vocational psychology suggests that reasons why individuals formulate or persist with a particular goal can directly influence their engagement in career preparation tasks (i.e., gaining experience, networking) often needed to achieve those goals (Porfeli and Vondracek 2007). Individuals are more likely to set and strive for goals if they perceive themselves as capable, find the goal intrinsically motivating (i.e., enjoyable, interesting), and feel as though the goal is part of their self-concept (Deci and Ryan 2000). Conversely, people would be less motivated to pursue goals that are extrinsically motivated and externally regulated (i.e., external demands and rewards) or involves internal conflict due to external pressure (Deci and Ryan 2000). Similarly, selecting a goal that corresponds to personal interests and values increases the probability of goal attainment (Porfeli and Vondracek 2007). Indeed, goals established in harmony with one’s intrinsic values and interests, as opposed to conflicting goals set by other people, greatly affects individuals’ goal progression (Koestner et al. 2002).

Research that examines the academic and career goals of ethnically diverse students finds that they report both individual and contextual motivations for pursing higher education (King et al. 2008). For instance, Phinney et al. (2006) found that ethnically diverse college students reported multiple reasons for attending college including career/personal, humanitarian, expectation, and encouragement motivations. Career or personal motivations are characterized by an individualistic focus that can be driven by personal interest, intellectual curiosity, and the desire to attain a rewarding career. Studies find that ethnically diverse college students perceive a linear relationship between academic success and upward mobility (Dennis et al. 2005). A humanitarian motivation reflects a collectivistic or altruistic orientation, where the individual is concerned with helping others. A number of studies among ethnically diverse college students find that young adults report humanitarian motivation in their academic and career pursuits. That is, Black students are often motivated to persist academically and vocationally in order to be a source of pride to the Black community (McGee and Bentley 2017) and address the underrepresentation of Black professionals (McCallum 2017). Encouragement motivation refers to perceived encouragement from important people in teens’ lives. A myriad of studies find that social support from parents, teachers, and other important individuals in youth’s lives decreases perceptions of educational barriers (McWhirter et al. 2007), increase college planning behaviors (Farmer-Hinton 2008), and career exploration and career planning (Rogers et al. 2008). Finally, expectation motivations reflect youth’s drive to meet the expectations of their parents and a sense of responsibility for meeting these goals. Latinx youth who consider their parents’ academic and career expectations in their academic planning do so in complex ways (Martinez 2013), citing the external pressure as a motivational and limiting factor. Similarly, one study among college-aged women found that career conversations with parents often resulted in negative emotions (e.g., feeling frustrated, confused and inferior, anxious in response to parental pressure), which negatively impacted their career exploration (Corey and Chen 2019). However, some participants believed that parental pressure increased their motivation toward career goals and allowed them to increase their perception of career options for their future. Still, one study found that pressure from family to succeed was not related to college adjustment, commitment to college, or college grade point average (Dennis et al. 2005).

Studies suggest that extent of youth’s engagement in academic and career activities is a result of multiple factors that may inhibit or promote development. For example, one study found that students motivations for higher education included both internal (e.g., self-improvement and achieving life goals) and external reasons (e.g. family expectations; Kennett et al. 2011). Interestingly, few studies have examined multiple motivators in one study or have examined how varied motivations may impact Black and Latinx youth’s engagement in academic and career activities. Certainly, the motivations included in the current study are not meant to be exhaustive nor entirely exclusive.

Critical Consciousness and Motivations for Post High School Plans

Extensive research has examined critical consciousness and motivations for post-secondary plans in the context of academic and career development, but no study has examined these factors together. Career development theory suggests that engagement in academic and career activities is a result of reciprocal interrelationships between internal and external factors (Lent et al. 2000). Thus, this study conceptualizes dimensions of critical consciousness as precursors to developing motivations for post-high school plans.

A critical understanding of social inequality coupled with identity development during adolescence may facilitate greater career exploration associated with marginalized youth’s lived experiences, values, and goals (Gregor et al. 2020). This process may help youth establish personal reasons (i.e., career/personal; humanitarian) for pursuing post high school plans associated with addressing unjust conditions they have experienced (Solórzano and Bernal 2001). Feeling of social responsibility, political efficacy, and experience in critical action may help crystalize youth’s perceptions of future selves within career paths aligned with their personal goals (Flanagan and Levine 2010). That is, youth who feel empowered and capable of enacting change in their communities may, over time, transform their personal experiences with marginalization into personal reasons for pursing civic careers. Youth who have direct experiences with the political system may gain insight into how they can make tangible changes with their careers. As previously stated, studies find that Black (McGee and Bentley 2017) and Latinx (McWhirter et al. 2019) students perceive civic careers as a form of political action and resistance to oppression. Pursing civic careers via higher education interestingly, reflects greater personal/career and humanitarian motivation. In other words, these motivations are not exclusive, but rather complementary among young adults of color.

Dimensions of critical consciousness may also help shape how youth perceive and utilize their personal relationships in their academic and career development. For instance, youth who understand the many barriers associated with their own success may understand the importance of attaining social support to help alleviate the negative effects of oppression (Luginbuhl et al. 2016). However, a critical understanding of systemic inequality may not always warrant action. As previously mentioned, perceived agency in creating positive changes may be key in behavior. Sociopolitical efficacy may encourage youth to engage in critical action and seek educational opportunities. Studies on youth organizing suggest that mentors in these spaces promote youth’s critical consciousness development (Albright et al. 2017) and academic and career development (Rogers and Terriquez 2013). It may be that continued engagement in collective critical action, such as in youth organizing, may lead to greater interaction with mentors and other important individuals (Nicholas et al. 2019).

Parents play a critical role in youths academic and career development. Indeed, Latinx parents often support their children’s academic and career development via cultural capital (Guzmán et al. 2018). Still, studies find that youth perceptions of parental involvement may cause internal dilemmas (Martinez 2013). It is plausible that a critical understanding of social inequality and sociopolitical efficacy may prompt youth to consider their parents’ expectations in the context of generational cumulative disadvantage, and perceive that as a motivating factor in their academic and career pursuits (Espino 2016). However, coupled with the reality of limited institutional opportunities in low-resourced communities (Flanagan and Levine 2010), greater sociopolitical efficacy may lead youth to feel burdened by the responsibility of changing the status quo and meeting high parent expectations.

The Current Study

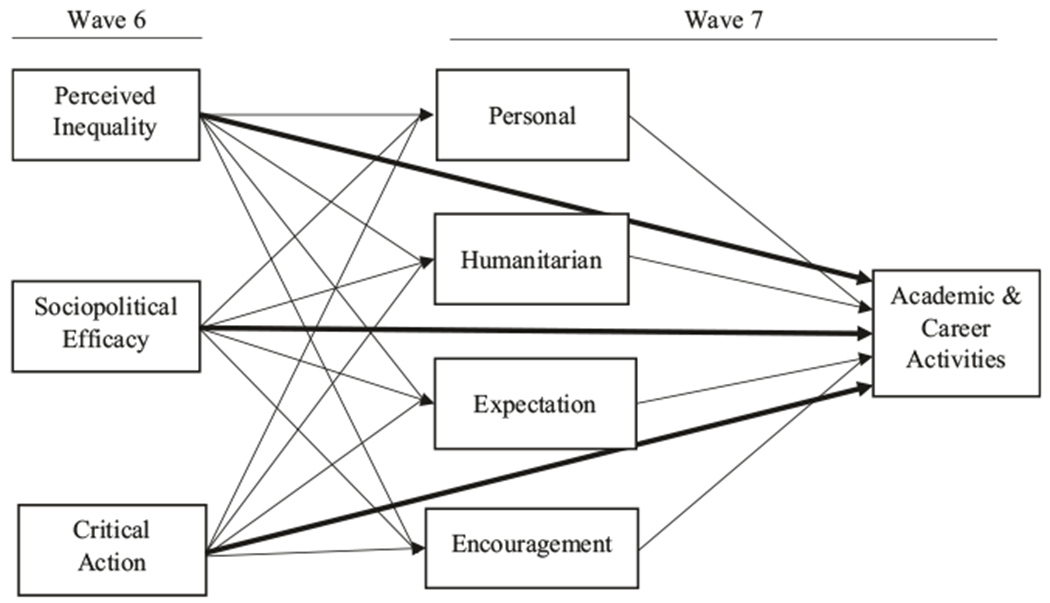

To better understand the mechanisms that facilitate the role of critical consciousness on youth academic and career development, this study examined the mediating role of motivations for post high school plans in the relationship between dimensions of critical consciousness and academic and career activities among Black and Latinx youth (Fig. 1). Based on previous research, it is expected that perceived inequality, sociopolitical efficacy, and critical action will be positively related to career/personal, humanitarian, and encouragement motivations, which will be subsequently related to greater academic and career activities. Given the previously mentioned mixed results on familial pressure to succeed, testing the role of expectation motivation will be considered an exploratory analysis in the relations between dimensions of critical consciousness and academic and career activities.

Fig. 1.

Proposed analytic model including direct paths from indicators of critical consciousness to indicators of motivations and from motivations to academic/career activities. Bold lines indicate direct paths from indicators of critical consciousness to academic/career activities. Correlations between indicators of critical consciousness and between motivations were included in the model. Model adjusts for youth age, gender, race/ethnicity, and income-to-needs ratio. Correlation and covariate paths are not shown here for clarity of presentation

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Data for this study come from a sample of predominantly Black and Latinx youth living largely in high-poverty, Chicago neighborhoods (Raver et al. 2009, 2011). Youth and their families were originally recruited into the study between 2004 and 2006, when the children were in preschool, to participate in a socioemotional intervention trial implemented in Chicago Head Start programs. Upon completion of the original intervention study, participants were assessed at an additional seven points in time.

The short-term longitudinal data used in this study come from waves six and seven of the larger study. Wave six was carried out in the spring of 2017 when youth were on average in 10th/11th grades (N = 432). After receiving parental consent and youth assent, data were collected from youth at their schools by a team of trained assessors as a part of a larger computerized survey battery. During the summer of 2018 when youth were on average entering 12th grade, youth were asked to complete survey items related to post-high school plans and goals (W7; N = 277). Youth completed the survey over the phone with a trained assessor. Youth were compensated for their participation at each assessment. This research has been approved by three independent university-based Institutional Review Boards.

The analytic sample for this study consists of 191 youth who have complete data on mediator and outcome variables collected at the wave seven assessment. The majority of youth in the study sample were female (59%) and Black (66%) (Table 1). On average, youth were 16 years old (SD = 0.80) at the wave six assessment. Averaging across all waves of data, the average income-to-needs ratio (INR) for the sample was 0.83 (SD = 0.65), indicating that the majority of youth lived in households whose income and family size placed them below the national poverty line (defined as having an income-to-needs ratio equal to or <1) for the majority of their lives. At wave seven, youth were asked about what they plan to be doing five years after high school. The item allowed participants to indicate on a four-point Likert type scale how likely they were to continue in academic and career trajectories. On average, the majority of teens reported that they are more likely to attend a 4-year college (M = 3.37, SD = 0.88), followed by community college (M = 2.48, SD = 1.11), and lastly a vocational training college (M = 1.71, SD = 0.99). On average, teens reported planning on working full time for pay (M = 3.17, SD = 0.92), followed by working part time for pay (M = 3.17, SD = 0.92), and lastly getting an unpaid internship (M = 2.18, SD = 1.1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 191)

| N (%) | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 126 (66) | |

| Latinx | 55 (29) | |

| Other | 10(5) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 113 (59) | |

| Male | 78 (41) | |

| Income-to-needs ratio | 0.85 (0.63) | |

| Age wave six | 16.00 (0.80) | |

| Perceived inequality | 3.05 (1.07) | |

| Political efficacy | 1.73 (1.31) | |

| Critical action | 4.03 (0.79) | |

| Personal motivation | 4.26 (0.67) | |

| Humanitarian motivation | 3.99 (0.78) | |

| Expectation motivation | 3.45 (0.83) | |

| Encouragement motivation | 4.14 (0.81) | |

| Academic and career activities | 3.39 (1.04) |

Measures

Three measures of critical consciousness were collected: perceived inequality, sociopolitical efficacy, and critical action. These predictor variables were collected from youth at the wave six assessment.

Perceived inequality (PI)

Three items from the PI subscale of the Critical Consciousness Scale (CCS; α = 0.87; Diemer et al. 2017) were used. This subscale is used to measure youth’s critical awareness and analysis of societal inequalities, including race, gender, and/or class-based discrimination in access to quality education and opportunities. Questions were rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (e.g., 1 = “Strongly Disagree”, 5 = “Strongly Agree”), and include the following: “Poor children have fewer chances to get a good high school education”, “Certain racial or ethnic groups have fewer chances to get ahead”, and “Poor people have fewer chances to get ahead”. Item responses were averaged with higher scores reflecting greater perceived inequality.

Sociopolitical efficacy (SE)

Four items similar to the items used by Diemer and Rapa (2016), as a proxy for internal SE, were used in the current study (α = 0.83). Youth responded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”. Example items included “It is important to fight against social and economic inequality” and “I can make a difference in my community”. Item responses were averaged with higher scores reflecting greater sociopolitical efficacy.

Critical action (CA)

Youth responded to five items taken from the Sociopolitical Action subscale of the CCS (Diemer et al. 2017). Response options were changed from a five-point Likert type scale to yes/no options. Some items were altered slightly to make them relevant to adolescents’ experiences with social media. These questions were chosen to reflect a range of sociopolitical involvement (e.g., “Have you posted on social media about a social justice or political issue?” to “Have you worked on a political campaign?”) and content that was germane to current events covered on local and national news media at that time (e.g., “Have you participated in a gay rights, pro-environment or social justice group?”). Additional items included “Have you participated in a discussion about a social or political issue, such as immigration or climate change?” and “Have you joined in a protest march, political demonstration, or political meeting?” Questions reflected behaviors engaged in during the prior six months. Responses were summed to create a measure of the total number of sociopolitical behaviors engaged in. This measurement of critical action is consistent with other studies on Black and Latinx youth (Roy et al. 2019; Roy et al. 2019).

Motivations

Items were drawn from the Student Motivation for Attending University—Revised measure (Phinney et al. 2006) to asses youth’s reasons to pursue plans after high school (e.g., career/personal, humanitarian, default, expectation, prove worth, encouragement, and family). Given that teens’ plans may vary (e.g., work, college, work and college), items were slightly modified (e.g., changed “I often ask myself why I’m in university” to “I often ask myself why I chose this plan”) to capture a broader range of post-high school plans. Items were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1–5 (e.g., 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”).

To keep the survey at a reasonable length, 25 of the original 33 items were administered. In an effort to keep most items on each of these subscales, items concerned with the highest loadings were retained. A confirmatory factor analysis with correlated errors was conducted to make sure that individual items loaded on the original sub-domains. To improve the reliability of the construct’s scale correlated errors were entered in the model. This included correlated errors for items addressing similar topics and using similar wording (e.g., errors for the two career/personal items addressing earnings were correlated with one another). The model fit statistics indicated that the model fit the data well, [(χ2(242, N = 264) = 412.94); RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI = [0.043, 0.060]); CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.07]. The results indicated that the items used were effective in tapping into six independent sources of motivations for post-high school plans: career/personal, humanitarian, default, expectation, prove worth, and encouragement. Unlike the original measure, items that captured “help family” were dropped as a factor due to it having only 2 items. Moreover, items that reflected default and prove worth motivations were dropped from these analyses because they were not related to the other key variables. Additional statistical results (e.g., factor loadings) are available upon request to the first author.

Personal/Career Motivation consists of six items (α = 0.85) that reflect youth’s reasons for pursing college/career as a means for gaining money, a good job, and status. Example items included “To achieve personal success”, “To help me improve my intellectual capacity”, and “To achieve a position of higher status in society”. Humanitarian Motivation consists of four items (α = 0.82) that describe academic/career motivations driven by a desire to help people and improve social conditions. Example items included “To contribute to the improvement of the human condition”, “To make meaningful changes to the ‘system’”. Encouragement Motivation consists of three items (α = 0.75) that reflect youth’s reasons for pursing academic/career goals because of encouragement received from a mentor or others. Example items included “I was encouraged by a mentor or role model”, “There was someone who believed I could succeed”. Expectation Motivation consists of four items (α = 0.65) that reflect youth’s reasons for pursing academic/career goals as a response to pressure from family members. Example items included “There were pressures on me from parents/family”, “Would let parents/family down if I didn’t succeed”. Aggregate motivation scores were based on a mean of items with greater scores reflecting greater motivations within each subscale.

Academic and Career Activities

Six items from the Career Planning subscale of the Career Development Inventory (α = 0.85; CDI; Super et al. 1982) were collected. Items were slightly modified given that teens’ plans may involve work and/or college (e.g., changed “Talking about career plans with an adult who knows something about me” to “Talking about career/education plans with an adult who knows something about me”). Items were answered on a five-point Likert scale from 1–5 (e.g., 1 = “I have not yet given any thought to this” to 5 = “I have made definite plans, and know what to do to carry them out”.) Example items include “Taking classes which will help me in college, job training, trade school, or on the job” and “Getting money for college or for job training/trade school”. Composite scores were calculated based on an average of the items with higher scores reflecting greater participation in academic and career activities.

Demographics

Demographic variables were used as covariates in path models. Youth gender was dummy coded such that females were coded as 1 and males were coded as 0. Age is represented in years and was collected at wave six when youth were in 10th/11th grade. Race/ethnicity was coded so that Black is 1 and Latinx/Other is 0. Socioeconomic status is represented as an income-to-needs ratio (INR; Moore et al. 2009) which compares a family’s income to the minimal economic resources required for a family of that size. The INR is computed by dividing the total family income by the Federal Poverty Threshold for a given year and family size. The INR measure is based on caregivers’ reports of family income and household size collected at waves 1 through 5. INR was calculated at each wave and then averaged across waves for individuals who had at least four waves of valid data.

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive analyses were performed in SPSS Version 27 and structural equation models were estimated in Mplus 7.4. Preliminary analyses examined variable distributions and potential biases associated with missing data. Rates of missing data were within acceptable range, 0–5% across all variables. Still, missing data patterns were inspected to determine the appropriate data analytic strategy for handling missing values. The data were determined to be missing at random (MAR) given the significant Little’s MCAR test (χ2(38) = 58.63, p < 0.05). Mplus software is considered appropriate for modeling data under MAR condition as it by default applies a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) model estimator to models with missing data to produce unbiased parameter estimates (Muthén and Muthén 2017).

Path models were evaluated using traditional fit indices (Chi-square test of model fit; Root mean square error of approximation, RMSEA; Standardized root mean square residual; SRMR) and comparative fit indices (Comparative Fit Index, CFI; Tucker-Lewis Fit Index, TLI). Acceptable model fit values for RMSEA and SRMR are 0.08 or lower and for CFI and TLI are greater than 0.90, with values greater than 0.95 preferred (Kline 2016). One model (Fig. 1) was fit to examine the indirect effect of four distinct motivations in the relationships between three indicators of critical consciousness and youth’s academic/career activities. The model includes directional paths from the three indicators of critical consciousness to each of the four motivations. Additional paths were estimated from critical consciousness and motivations to academic and career activities. Youth gender, age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status were included as covariates in the model. Current approaches to testing mediation involve testing the indirect effect using bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals based on 5000 sample replicates (MacKinnon et al. 2007). Resampling methods such as bootstrapping provide more accurate confidence limits for the mediated effect because they accommodate the non-normal distribution of the product. Bootstrap standard errors and confidence intervals are available with missing data. Correlations among covariates, between motivation variables, and between indicators of critical consciousness were added based on modification indices.

Results

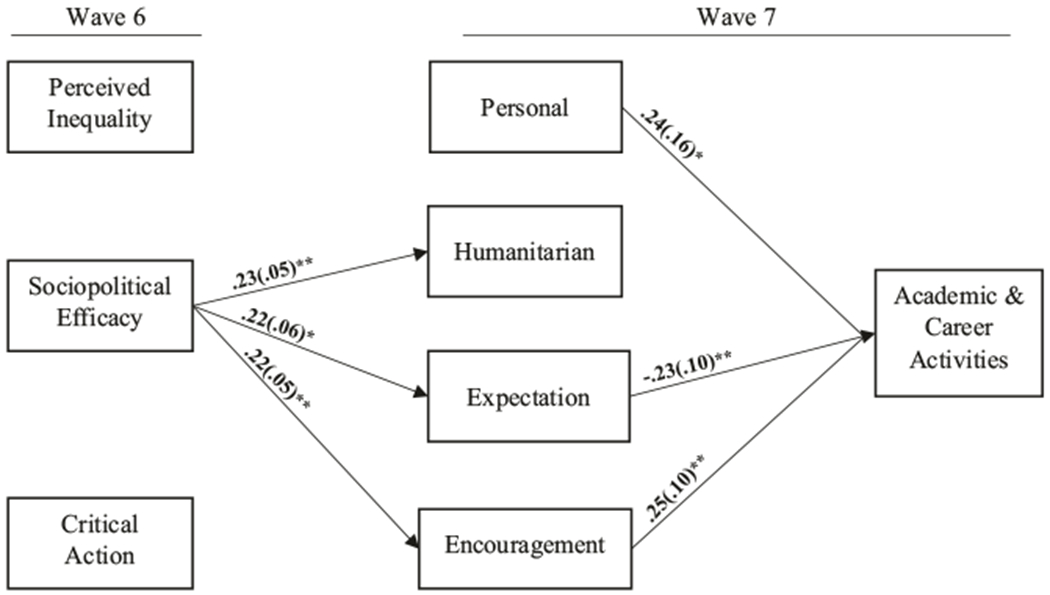

Bivariate correlations between key variables of interest are shown in Table 2. The multiple mediator path model fit the data well, [(χ2(10, N = 191) = 12.21); RMSEA = 0.03 (90% CI = [0.000, 0.089]); CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.03] (Fig. 2). Sociopolitical efficacy at wave six predicted greater humanitarian motivation (β = 0.23, SE = 0.05, p = 0.006), greater expectation motivation (β = 0.22, SE = 0.06, p = 0.012), and greater encouragement motivation (β = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p = 0.017) at the wave seven assessment. Personal/career motivation (β = 0.23, SE = 0.16, p = 0.024) and encouragement motivation (β = 0.25, SE = 0.11, p = 0.002) were positively related to academic and career activities. In contrast, greater expectation motivation was related to less engagement in academic and career activities (β = −0.23, SE = 0.10, p = 0.003).

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations for study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived inequality | – | 0.11 | 0.16* | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.16* | −0.02 | −0.00 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| 2. Political efficacy | 0.35** | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.21** | 0.24** | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| 3. Critical action | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.12 | −0.16* | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.19* | |||

| 4. Personal motivation | 0.30** | 0.41** | 0.65** | 0.38** | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | ||||

| 5. Humanitarian motivation | 0.48** | 0.29** | 0.09 | 0.25** | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.01 | |||||

| 6. Expectation motivation | 0.42** | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.19** | 0.10 | ||||||

| 7. Encouragement motivation | 0.38** | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |||||||

| 8. Academic and career activities | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.16* | 0.20** | ||||||||

| 9. Race (Black = 1) | −0.04 | −0.17* | −0.52** | |||||||||

| 10. Gender (Female = 1) | −0.04 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| 11. Income to needs ratio | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| 12. Age wave 6 |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.10

Fig. 2.

Path model results. Standardized beta estimates and SEs are shown

Estimation of the indirect effects indicated significant indirect pathways from sociopolitical efficacy to academic and career activities via encouragement motivation and expectation motivation, albeit in opposite directions (Table 3). Greater sociopolitical efficacy was related to higher levels of expectation motivation, which was subsequently predictive of less engagement in academic and career activities (β = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.01], p = 0.039). Greater sociopolitical efficacy also was related to higher levels of encouragement motivation, which was subsequently predictive of engagement in more academic and career activities (β = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08], p = 0.036). There was no significant indirect effect of perceived inequality or critical action on academic and career activities through any of the motivation variables or of sociopolitical efficacy to academic and career activities via humanitarian or personal/career motivation.

Table 3.

Multiple mediator path model results

| b | SE | B | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct paths | ||||

| CC → Motivation | ||||

| PI → Personal | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.16, 0.04 |

| SPE → Personal | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.14 | −0.03, 0.17 |

| CA → Personal | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.15, 0.21 |

| PI → Humanitarian | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.17, 0.08 |

| SPE → Humanitarian | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.23** | 0.04, 0.35 |

| CA → Humanitarian | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.16 | −0.04, 0.32 |

| PI → Expectation | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.15 | −0.03, 0.20 |

| SPE → Expectation | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.22* | 0.03, 0.24 |

| CA → Expectation | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.04 | −0.22, 0.15 |

| PI → Encouragement | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.17, 0.07 |

| SPE → Encouragement | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.22** | 0.04, 0.23 |

| CA → Encouragement | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.10, 0.30 |

| CC and Motivation → Activities | ||||

| PI → Activities | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.11, 0.16 |

| SPE → Activities | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.08, 0.15 |

| CA → Activities | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.18, 0.23 |

| Personal → Activities | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.24* | 0.06, 0.70 |

| Humanitarian → Activities | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.08 | −0.16, 0.37 |

| Expectation → Activities | −0.30 | 0.10 | −0.23** | −0.51, −0.11 |

| Encouragement → Activities | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.25** | 0.12, 0.54 |

| Indirect paths | ||||

| PI → Personal → Activities | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.06, 0.02 |

| PI → Humanitarian → Activities | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03, 0.02 |

| PI → Expectation → Activities | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.07, 0.02 |

| PI → Encouragement → Activities | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.06, 0.03 |

| SPE → Personal → Activities | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02, 0.09 |

| SPE → Humanitarian → Activities | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03, 0.07 |

| SPE → Expectation → Activities | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.05* | −0.10, −0.01 |

| SPE → Encouragement → Activities | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06* | 0.01, 0.11 |

| CA → Personal → Activities | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05, 0.06 |

| CA → Humanitarian → Activities | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.05 |

| CA → Expectation → Activities | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.05 |

| CA → Encouragement → Activities | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03, 0.07 |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.10; All models control for race, gender, age, and income-to-needs ratio

CC critical consciousness, PI perceived inequality, SPE sociopolitical efficacy, CA critical action, 95% CI presented are standardized

Sensitivity Analysis

Given that the mediator and outcome variables were both collected at the wave seven assessment, an additional model was examined wherein academic and career activities was considered the mediator and motivations as the outcomes (i.e., CC → Academic and Career Activities → Motivations). The model fit the data well, [(χ2(10, N = 191) = 12.39); RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI = [0.000, 0.090]); CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.03]. Some direct relationships were found. Similar to the main model, sociopolitical efficacy at T1 was significantly associated with greater humanitarian motivation (β = 0.20, SE = 0.05, p = 0.007), encouragement motivation (β = −0.13, SE = 0.04, p = 0.009), and expectation motivation (β = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p = 0.010). Engagement in academic and career activities at T2 was associated with greater personal/career motivation (β = 0.37, SE = 0.05, p = 0.000), humanitarian motivation (β = 0.33, SE = 0.05, p = 0.000), and encouragement motivation (β = 0.36, SE = 0.06, p = 0.000). The mediation analyses indicate that there is no indirect effect of academic and career activities on the relationship between dimensions of critical consciousness to indicators of post-high school motivations. These results suggest that the original model best describes these relationships. Additional statistical results are available from the first author upon request.

Discussion

Low-income Black and Latinx youth contend with structural deficits in their schools and communities as they prepare for academic and career pursuits (Blustein et al. 2005). Critical consciousness has been found to assist youth in navigating racist academic (Cabrera et al. 2014) and career structures (Kozan et al. 2017) and is associated with increased academic (Seider et al. 2020) and career well-being (Rapa et al. 2018). Still, there is very little research that speaks to how critical consciousness helps youth engage their environments to prepare them for emerging adulthood or how critical consciousness informs mechanisms that motivate youth’s post-high school plans. The current study contributes to this growing body of work by examining the explanatory role of motivations for post-high school (i.e., career/personal, humanitarian, encouragement, expectation) in the relationship between critical consciousness and engagement in academic and career activities while in high school.

The results of this study suggest that critical consciousness, specifically sociopolitical efficacy, is positively related to humanitarian, encouragement, and expectation motivations for post-high school plans. Moreover, there exists an indirect pathway between sociopolitical efficacy and academic and career activities via encouragement and expectation motivations, albeit in different directions. Sociopolitical efficacy positively predicted perceived encouragement from important individuals (e.g., mentors), which was subsequently related to greater academic and career activities. At the same time, youth’s sociopolitical efficacy positively predicted greater perceptions of pressure from parents and family members to succeed, which was related to less engagement in behaviors towards future academic and career plans. These results indicate that youth’s perceptions of their ability to affect social change shapes perceptions of both the supports for and pressure to succeed, which in turn, impacts engagement in activities that prepare them for emerging adulthood.

As hypothesized, the current study found that youth who perceived greater agency in affecting social change, also perceived greater support for their post-high school plans from important people in their lives. This, in turn, was related to greater engagement in academic and career activities. These results support previous studies that find sociopolitical efficacy is related to greater academic and vocational outcomes such as salience of work and connection to future career (Diemer and Blustein 2006), engagement in school (Godfrey et al. 2019), and higher intent to persist in college (Cadenas et al. 2018). Furthermore, these results suggest that youth’s continued interaction with mentors and other important individuals facilitate the positive effect of sociopolitical efficacy. It may be that youth’s engagement in their future plans indicate their evolving level of agency, such that as students became more aware of their role in producing social change, they also develop more capacity for agency in building relationships that will help them obtain academic and career goals. Indeed, one study found that youth’s understanding of social inequality and motivation to change inequality (captured as on concept of critical reflection) was associated with greater autonomous academic motivation, which subsequently predicted greater educational and vocational expectation outcomes (Luginbuhl et al. 2016). As such, it may be that perceived sociopolitical agency enhances students’ efforts to secure relational support from important individuals in their lives knowing that people like institutional agents (i.e., an individual who occupies one or more hierarchical positions of relatively high-status and authority like teachers and community organizers; Stanton-Salazar 2011) are critical in their pursuit of higher education and career security. Continued engagement and relationship building may over time allow youth to perceive encouragement from mentors in their political and academic activities (Albright et al. 2017). These sources of support may help youth develop the skills necessary to obtain their goals (Sánchez et al. 2008), access resources (Stanton-Salazar 2011), and find encouragement to pursue their plans (Diemer 2007), allowing them to engage in greater academic and career activities.

The results revealed that as youth become aware of their role in the political system and their ability to change social inequality, they are more likely to perceive greater pressure from family members to succeed in a particular career and/or college path. This perceived pressure negatively affects their engagement in academic and career activities, such that it impedes their actions towards these expected plans. A host of literature among students of color finds that parents play a positive role in motivating their academic and career goals towards entering civic careers (Guzmán et al. 2018; Suárez-Orozco et al. 2015). However, some studies do find that family involvement is related to poorer engagement in academic and career activities as a result of internal conflict between individual and family expectations (Martinez 2013). No studies, however, have previously examined how sociopolitical efficacy affects youth perception of parental involvement in their academic and career pursuits. It is plausible that youth who feel responsible for changing the status quo also have to meet high parental expectations. This situation may result in youth feeling overwhelmed, which may negatively impact their academic and career engagement. Indeed, low-income Black and Latinx teens may not have the luxury of being excluded from their family’s financial issues and may use that as a source of inspiration for their personal future academic and career pursuits (Espino 2016). However, this motivation coupled with the reality of ecological challenges and barriers to political action in many low-resource communities, may further marginalize youth in their political, academic, and career pursuits (Blustein et al. 2005). It is plausible for low-income Black and Latinx youth to feel overburdened for being responsible in making tangible changes to the status quo for themselves, their family, and for society at large. Certainly, youth’s perceptions of carrying the financial future success of their families on their shoulders and changing systems of oppression can be debilitating.

Theories on civic engagement may help explain this funding further. For instance, studies on youth civic engagement (Wray-Lake and Abrams 2020) and psychological empowerment (Christens et al. 2018) suggest that youth may need from sociopolitical efficacy and social connection to remain hopeful and engaged. In other words, youth may benefit from an understanding that collective action, in addition to individual success, is needed to create systemic changes. Among Black youth, one study found that familiarity with collective struggle may be associated with human agency and academic motivation (O’Connor 1997). Future studies should investigate how social connection, sociopolitical efficacy, and perceptions of parent involvement affect youth’s engagement in academic and career preparation.

Importantly, these results suggest that youth, even youth who endorse greater agency in effecting social change, may need additional resources that allow them to build and achieve individual goals within the context of familial expectations. These results suggest that programming aimed at improving youth outcomes needs to consider the structural factors that add pressure to families and communities, which may indirectly affect youth’s engagement in academic and career activities. It is important for programming designed to promote sociopolitical efficacy to address how youth may interpret their roles and responsibilities differently, as well as how youth may feel both supported and burdened at the same time. More importantly, these results suggest that programming aimed at empowering youth should also teach youth how to self-preserve, since self-preservation is also considered a form of political action among marginalized groups (Lorde 2017).

It is important to note that motivating factors are not mutually exclusive, and that youth may have multiple sources of motivation underlying their academic and career plans. Indeed, correlations between the different sources of motivation indicate moderately low to high positive relationships (Pearson’s r range = 0.29–0.65). Specifically, encouragement and expectation motivations were moderately linked (r = 0.42), suggesting that some youth may be simultaneously experiencing the conflicting motivating factors of both encouragement and expectations. The current study, and the chosen analysis, may not have captured how both encouragement from mentors and high expectations from parent’s impact youth academic and career engagement. Qualitative and mixed-methods studies may be more suitable in explaining whether these motivations cooccur, compound, or follow each other and how they impact youth development.

Regarding direct associations, the current study revealed that higher levels of sociopolitical efficacy were related to greater humanitarian motivation. These results suggest that as youth become more confident in their ability to affect social change, they are more likely to endorse being motivated by a concern to help others. However, this concern does not predict engagement in academic and career-related activities. This may be because the link between helping others and engagement in academic and career activities often does not develop until college (Solórzano and Bernal 2001; McCallum 2017). Future research should consider how humanitarian motivations developed in high school are related to critical consciousness and academic and career achievement in adulthood.

The results revealed that career/personal motivation was related to greater engagement in academic and career activities, but none of the dimensions of critical consciousness significantly predicted career/personal motivation. Given the high mean on career/personal motivation (4.26 on a five-point scale), it may be that the null findings for career/personal motivation are due to the low variability in the sample. These results indicate the low-income, Black and Latinx youth are driven by personal/career success which motivates them to engage in behaviors that will prepare them for college and career plans.

Contrary to prior work, the current study failed to find a direct link between dimensions of critical consciousness and academic and career activities. Interestingly, correlations between variables of interest indicate that none of the dimensions of critical consciousness were significantly related to academic and career activities (Table 2). One prior study found that Latinx youth who endorsed greater critical consciousness reported greater school engagement, compared to those with lower level of critical consciousness (McWhirter and McWhirter 2016). One important distinction from the current study is that the McWhirter and McWhirter (2016) study sample consisted of students who attended a leadership conference. It may be that youth who are already engaging in extra-curricular activities, like attending leadership conferences, may also be engaging in other extra-curricular activities related to post-high school plans. The current study, among a sample of low-income, Black and Latinx youth, builds on the current literature by examining the relationship between critical consciousness and academic and career activities among youth who may have fewer resources to support their participation in these types of activities. It may be that critical consciousness directly leads to participation in academic and career activities when young people have more time and opportunity to already be engaged in professional development opportunities.

Similar to the results of the correlation analyses, path model results suggest that critical reflection and critical action are not associated with engagement in academic and career activities. It may be that that these dimensions of critical consciousness impact other aspects of academic and career development than those explored in the current study. For example, one study found that sense of sociopolitical efficacy was associated with salience of work role and connection to future career, while critical reflection was related to vocational identity in a sample of urban youth (Diemer and Blustein 2006). Furthermore, the results from the current study stand in contrast to a recent study that found critical reflection and critical action, but not sociopolitical efficacy, were related to higher grade point averages and college entrance exams scores (Seider et al. 2020). Given that preparation for emerging adulthood can be measured in multiple ways, future studies should continue to investigate how different dimensions of critical consciousness affect youth’s different dimensions of post-secondary career and college aspirations, including behaviors, intentions, and connections to academic and career goals.

The current study did not find any evidence of the role of critical reflection and critical action on career/personal and humanitarian motivation. It may be that youth in high school are more aware of their environmental supports and pressure rather than an internal drive for their academic and career plans (whether it be for personal gain or altruistic reasons). These motivations may be shaped in higher education (Solórzano and Bernal 2001; McCallum 2017) rather than in high school. It may be worthwhile for future research to investigate how these motivations developed in high school are related to critical consciousness and college and career achievement in adulthood.

There are a number of limitations to consider when interpreting these results. First, the ability to draw conclusions about causality is limited. Although the current study capitalized on longitudinal data and, as such, there is more confidence that the indicators of critical consciousness precede the measures of motivations and academic and career activities, youth’s motivations and activities were not assessed at earlier waves. Future studies should capitalize on longitudinal or experimental research designs to better estimate causal relationships between indicators of critical consciousness and academic and career plans over time. Relatedly, the longitudinal data come from two consecutive waves of data. Longitudinal datasets with multiple waves are better suited for mediation analyses. Ideally, researchers should assess youth at three or more time points which would allow measuring the mediator at the second time point and the outcome at the third time point in order to have robust evidence for causal pathways. Third, the measurements used to capture motivations for post high school plans are broad in nature. In particular, the interpretation around perceived encouragement is limited because the items are not specific to individuals (e.g., sibling, natural mentor, coach, teacher). More research should investigate which individuals in youth’s lives play a critical role in encouraging their academic and career preparation. Although previous research and theory suggest that youth may perceive their academic and career pursuits as critical action, the items used in this study (e.g., motivation, activities) are not grounded in the context of oppression. Furthermore, the outcome variable measured academic and vocational development in one combined variable. This limits the interpretation of the results such that the authors can only infer a general effect on post-high school plans rather than a direct relationship to different dimensions of academic and vocational outcomes important for youth development. Future studies should examine these outcomes separately to examine whether the results are driven by one outcome more than the other or if they are equally affected by varied motivations and critical consciousness dimensions. Finally, the findings are specific to the sample of the study: Black and Latinx youth living in high-poverty households in Chicago. Although this may limit the generalizability of the results, this study design is viewed as a strength as there is limited work that examines critical consciousness among Chicago youth. To learn more about this population and better understand the antecedents and consequences associated with youth development of critical consciousness and academic and career achievement, future studies should continue to explore these relationships in similar settings and in different contexts among more economically diverse samples.

The present study adds to existing empirical scholarship on the importance of critical consciousness in the positive development of youth of color by offering evidence of relations between academic and career activities, motivations for post high school plans, and critical consciousness in a sample of low-income, adolescents of color. The present study points to incorporating an ecological lens (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2006) to critical consciousness, academic, and career development among youth of color. Understanding youth’s perception of close relationships (e.g., pressure from parents/family; encouragement from important individuals) has implications for youth development research concerned with student success, vocational attainment, and preparation for emerging adulthood. Additionally, the current findings point to programming fostering youth critical consciousness as a potential mechanism for narrowing racial and economic opportunity gaps via individual academic and career goals. Educational programming could benefit from incorporating critical consciousness curriculum as a tool to help youth navigate racist academic and vocational structures. For instance, teaching youth about social inequality, engaging in social projects via youth participatory action research (Cammarota and Fine 2008) may increase youth agency and sociopolitical efficacy. More importantly, the current results suggest that critical consciousness programming will need to integrate how youth understand their role in changing social inequality in relation to their close relationships with important individuals (e.g., family members, teachers, mentors) to continue fostering youth’s positive development. This may indicate tasking educational agents (i.e., teachers, mentors) and schools with creating connections with parents and engaging youth, families, and communities to collectively join in social justice community action (Ginwright et al. 2005).

Conclusion

Research suggest that Black and Latinx youth are less prepared to enter college and obtain a high-status career in adulthood (Orfield et al. 2004). Critical consciousness has been found to be associated with greater academic (Seider et al. 2020) and career achievement (Rapa et al. 2018). To understand the mechanisms by which critical consciousness impacts youth academic and career preparation, this study examined a model wherein four different motivations for post high school plans (i.e., career/personal, humanitarian, encouragement from important individuals, expectation from parents/family) mediated the relationship between dimension of critical consciousness (i.e., perceived inequality, social political efficacy, critical action) and engagement in academic and career activities (e.g., taking classes that will prepare youth for college entry). The results suggest that greater sociopolitical efficacy is related to greater perceptions of encouragement, which was subsequently was related to greater engagement in academic and career activities during senior year of high school. At the same time, sociopolitical efficacy was related to greater perception of pressure from parents, which was then related to less engagement in academic and career activities. These findings suggest that youth’s sociopolitical efficacy and perceptions of close relationship with parents and mentors significantly impact their level of engagement in preparatory behavior meaningful for adulthood.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Federal Interagency School Readiness Consortium (NICHD 2R01 HD046160), which includes the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Administration for Children and Families, the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in the Department of Health and Human Services, the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services of the U.S. Department of Education. We also thank the Spencer Foundation (Grant #201800130), McCormick Tribune Foundation, and the Institute of Education Sciences and the U.S. Department of Education (Grant R305B140035). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. (1842398) awarded to M.U. and funding from the Institute of Education Sciences and the U.S. Department of Education (Grant R305B140035).

Biographies

Marbella Uriostegui is a doctoral student in the Department of Psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research interests includes critical consciousness among youth and young adults of color academic achievement; racial discrimination and stress; experiences of students of color in higher education; risk and resilience in the context of poverty and marginalized families.

Amanda L. Roy is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research interests include, neighborhood and environmental factors (e.g., noise exposure); income, poverty, racial/ethnic composition, crime, and organizational resources; health and well-being of adults, adolescents, and children, including adolescent self-regulation, and cognitive functioning.

Christine Pajunar Li-Grining is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Loyola University Chicago. Her research interests include, self-regulation, school readiness, and academic achievement; early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood; child care, early childhood education, and intervention; risk and resilience in the context of poverty and immigrant families; education and social policy.

Footnotes

Data Sharing and Declaration The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC Protocol # 2015-0782).

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

References

- Albright JN, Hurd NM, & Hussain SB (2017). Applying a social justice lens to youth mentoring: A review of the literature and recommendations for practice. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(3–4), 363–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso G, Anderson NS, Su C, & Theoharis J (2009). Our schools suck: Students talk back to a segregated nation on the failures of urban education. New York, NY: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold ME (2017). Supporting adolescent exploration and commitment: Identity formation, thriving, and positive youth development. Journal of Youth Development, 12(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(3), 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein DL, McWhirter EH, & Perry JC (2005). An emancipatory communitarian approach to vocational development theory, research, and practice. The Counseling Psychologist, 33 (2), 141–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Morris PA (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In Lerner RM & Damon W (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793–828). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NL, Milem JF, Jaquette O, & Marx RW (2014). Missing the (student achievement) forest for all the (political) trees: Empiricism and the Mexican American studies controversy in Tucson. American Educational Research Journal, 51(6), 1084–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas GA, Bernstein BL, & Tracey TJ (2018). Critical consciousness and intent to persist through college in DACA and US citizen students: The role of immigration status, race, and ethnicity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24 (4), 564–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota J, & Fine M (2008). Youth participatory action research: A pedagogy for transformative resistance. In Cammarota J & Fine M (Eds.), Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion (pp. 1–12). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota J (2007). A social justice approach to achievement: Guiding Latina/o students toward educational attainment with a challenging, socially relevant curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education, 40(1), 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Carter D (2008). Achievement as resistance: The development of a critical race achievement ideology among Black achievers. Harvard Educational Review, 78(3), 466–497. [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD, Byrd K, Peterson NA, & Lardier DT (2018). Critical hopefulness among urban high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1649–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey P, & Chen CP (2019). Young women’s experiences of parental pressure in the context of their career exploration. Australian Journal of Career Development, 28(2), 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, & Ryan RM (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JM, Phinney JS, & Chuateco LI (2005). The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority first-generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 46(3), 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA (2007). Parental and school influences upon the career development of poor youth of color. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(3), 502–524. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA (2009). Pathways to occupational attainment among poor youth of color: The role of sociopolitical development. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(1), 6–35. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA (2020). Pushing the envelope: The who, what, when, and why of critical consciousness. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 70, 101192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, & Blustein DL (2006). Critical consciousness and career development among urban youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 220–232. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, & Hsieh CA (2008). Sociopolitical development and vocational expectations among lower socioeconomic status adolescents of color. The Career Development Quarterly, 56(3), 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, & Rapa LJ (2016). Unraveling the complexity of critical consciousness, political efficacy, and political action among marginalized adolescents. Child Development, 87(1), 221–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, Rapa LJ, Park CJ, & Perry JC (2017). Development and validation of the Critical Consciousness Scale. Youth & Society, 49(4), 461–483. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, Wang Q, Moore T, Gregory SR, Hatcher KM, & Voight AM (2010). Sociopolitical development, work salience, and vocational expectations among low socioeconomic status African American, Latin American, and Asian American youth. Developmental Psychology, 46(3), 619–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino MM (2016). The value of education and educaci¢n: Nurturing Mexican American childrenas educational aspirations to the doctorate. Journal of Latinos and Education, 15(2), 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer-Hinton RL (2002). The Chicago context: Understanding the consequences of urban processes on school capacity. Journal of Negro Education, 71(4), 313–330. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer-Hinton RL (2008). Social capital and college planning: Students of color using school networks for support and guidance. Education and Urban Society, 41(1), 127–157. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan C, & Levine P (2010). Civic engagement and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children, 20(1), 159–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S, & Cammarota J (2002). New terrain in youth development: The promise of a social justice approach. Social Justice, 29(4), 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S, Cammarota J, & Noguera P (2005). Youth, social justice, and communities: Toward a theory of urban youth policy. Social Justice, 32(3), 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey EB, Burson EL, Yanisch TM, Hughes D, & Way N (2019). A bitter pill to swallow? Patterns of critical consciousness and socioemotional and academic well-being in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 55(3), 525–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor MA, Pino HVGD, Gonzalez A, Soto S, & Dunn MG (2020). Understanding the career aspirations of diverse community college students. Journal of Career Assessment, 28(2), 202–218. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán BL, Kouyoumdjian C, Medrano JA, & Bernal I (2018). Community cultural wealth and immigrant Latino parents. Journal of Latinos and Education, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Heberle AE, Rapa LJ, & Farago F (2020). Critical consciousness in children and adolescents: A systematic review, critical assessment, and recommendations for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 146(6), 525–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett DJ, Reed MJ, & Lam D (2011). The importance of directly asking students their reasons for attending higher education. Issues in Educational Research, 21(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- King N, Madsen ER, Braverman M, Paterson C, & Yancey AK (2008). Career decisionmaking: Perspectives of low-income urban youth. Spaces for Difference: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 1(1), 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koestner R, Lekes N, Powers TA, & Chicoine E (2002). Attaining personal goals: Self-concordance plus implementation intentions equals success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 231–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozan S, Blustein DL, Barnett M, Wong C, Connors-Kellgren A, Haley J, Patchen A, Olle C, Diemer MA, Floyd A, Tan RB, & Wan D (2017). Awakening, efficacy, and action: A qualitative inquiry of a social justice-infused, science education program. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 17(1), 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Lapan RT (2004). Career development across the K-16 years: bridging the present to satisfying and successful futures. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr, Herr KG, Barrios VR, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2019). Merit in meritocracy: Uncovering the myth of exceptionality and self-reliance through the voices of urban youth of color. Education and Urban Society, 51(4), 474–500. [Google Scholar]

- Lent RW, Brown SD, & Hackett G (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lent RW, Brown SD, & Hackett G (2002). Social cognitive career theory. In Brown D (Ed.), Career choice and development (pp. 255–311). San Francisco, CA: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lorde A (2017). A burst of light: and other essays. United States: Courier Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Luginbuhl PJ, McWhirter EH, & McWhirter BT (2016). Sociopolitical development, autonomous motivation, and education outcomes: Implications for low-income Latina/o adolescents. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 4(1), 43–59. [Google Scholar]