Description

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a serious complication of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and can be complicated by injury of the central nervous system (CNS). The most common CNS injury in DKA is cerebral oedema, diagnosed clinically in approximately 0.5%–0.9% of children with DKA.1–6 Subclinical cerebral oedema has been identified by MRI in up to 50% of cases of DKA.7 Intracranial thrombosis of arterial/venous origin can also occur during DKA. As cerebral oedema and CNS thrombosis can present similarly, timely neuroimaging is essential to identify pathology and direct therapies if the patient is not clinically improving after treatment for suspected cerebral oedema.

We describe an adolescent female who developed nausea and vomiting, headache and confusion at home. She was minimally responsive and was diagnosed with new-onset T1DM and severe DKA on hospital admission. Given clinical concern for cerebral oedema, she was treated with mannitol with mild neurological improvement. She had respiratory failure requiring intubation. Because of this minimal response to treatment in the setting of clinically declining neurological status, imaging was ordered and a non-contrast CT of the brain suggested mild cerebral oedema. CT-venogram demonstrated dural sinus thrombosis within the torcula and left transverse sinus (figure 1). DKA management was continued, mannitol and hypertonic saline were administered, anticoagulation therapy was initiated, and an external ventricular drain was placed to monitor intracranial pressure. Follow-up imaging with contrast-enhanced MRI and venography revealed progression of thrombus to include the right transverse sinus (figure 2). After 6 days, she was extubated, and neurologic exam slowly improved without deficits. She was transitioned to warfarin for anticoagulation, and follow-up MRI 10 months later showed full resolution of the thrombosis.

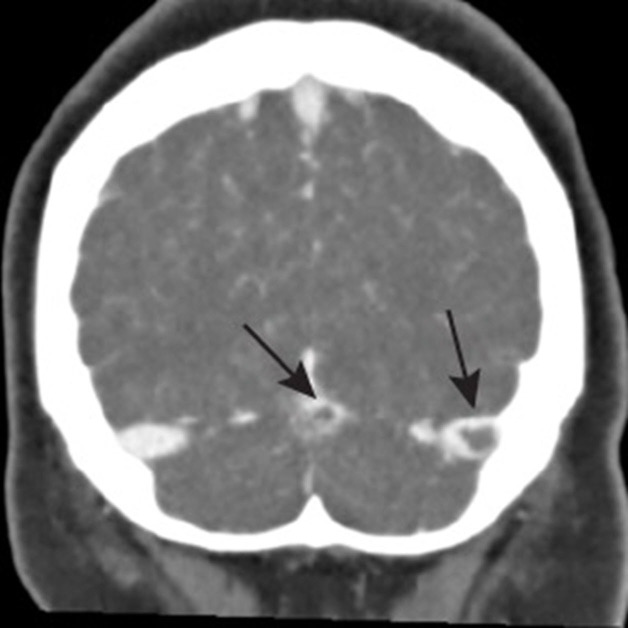

Figure 1.

Coronal CT venogram showing filling defects demonstrating area of thrombosis within the torcula (confluence of straight and transverse sinuses) and left transverse sinus (black arrows).

Figure 2.

MRI/MRV images (T1, post gadolinium). Thrombus within the torcula (A) and progression of thrombus into right transverse sinus (B, white arrows). MRV, magnetic resonance venography.

The most common neurologic abnormality diagnosed via imaging in youth with DKA is cerebral oedema. Cerebral oedema in children with DKA has a 20%–30% mortality rate.4 The pathophysiology of cerebral oedema involves multiple pathways.8 Hyperglycaemic and metabolic acidosis converge to produce hypoperfusion and subsequent hypoxic insult contributing to overall cytotoxic injury.8–13 Systemic and neuroinflammatory processes, impaired cerebrovascular autoregulation and reperfusion injury lead to the disruption of the blood–brain barrier and contribute to vasogenic injury.8–13 Clinically apparent cerebral oedema is more likely to occur with severe acidosis, severe hypocapnia and an elevated level of blood urea nitrogen.4 13 14 Other cerebral complications of DKA are less common and can include haemorrhagic or ischaemic infarction of arterial/venous origin.15 16 Stroke in children accounts for 10% of the neurologic complications seen with DKA.16 Multiple mechanisms predispose children with DKA to ischaemic stroke: cerebral oedema, increased blood viscosity due to hyperosmolality, severe dehydration, increased systemic inflammation, vascular endothelial injury and vasoconstriction.17 18 Focal deficits are rare and identification of DKA-associated thrombosis requires a high index of suspicion.19 Urgent diagnosis is critical because paediatric stroke is also associated with a high rate of lasting neurologic deficits.19 Cerebral oedema and intracranial thrombosis are CNS injuries that have high mortality and morbidity rates, making it critical to monitor children with DKA for changing neurologic symptoms.

Learning points.

This case highlights the importance of rapid treatment when cerebral oedema is suspected, and the importance of neuroimaging when patients with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and neurologic compromise do not respond to appropriate therapy for suspected cerebral oedema.

Although the vast majority of central nervous system injury in children in the setting of DKA is related to cerebral oedema, it is important for clinicians to consider ischaemic prothrombotic pathology in the differential diagnosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: JLB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DWS, MS-G and LST all provided detailed edits and critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors contributed to acquisition of data. All authors have reviewed and approved the final draft as submitted. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ho J, Pacaud D, Hill MD, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis and pediatric stroke. CMAJ 2005;172:327–8. 10.1503/cmaj.1032013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence SE, Cummings EA, Gaboury I, et al. Population-based study of incidence and risk factors for cerebral edema in pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. J Pediatr 2005;146:688–92. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin DL. Cerebral edema in diabetic ketoacidosis. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2008;9:320–9. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31816c7082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edge JA, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, et al. The risk and outcome of cerebral oedema developing during diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Dis Child 2001;85:16–22. 10.1136/adc.85.1.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wootton-Gorges SL, Glaser NS. Imaging of the brain in children with type I diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Radiol 2007;37:863–9. 10.1007/s00247-007-0536-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glaser N, Barnett P, McCaslin I, et al. Risk factors for cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. The pediatric emergency medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of pediatrics. N Engl J Med 2001;344:264–9. 10.1056/NEJM200101253440404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaser NS, Wootton-Gorges SL, Buonocore MH, et al. Frequency of sub-clinical cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. Pediatr Diabetes 2006;7:75–80. 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2006.00156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azova S, Rapaport R, Wolfsdorf J. Brain injury in children with diabetic ketoacidosis: review of the literature and a proposed pathophysiologic pathway for the development of cerebral edema. Pediatr Diabetes 2021;22:148–60. 10.1111/pedi.13152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuppermann N, Ghetti S, Schunk JE, et al. Clinical trial of fluid infusion rates for pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2275–87. 10.1056/NEJMoa1716816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sperling MA. Fluid composition, infusion rate, and brain injury in diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2336–8. 10.1056/NEJMe1806017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayashree M, Williams V, Iyer R. Fluid therapy for pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis: current perspectives. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2019;12:2355–61. 10.2147/DMSO.S194944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohn D, Daneman D. Diabetic ketoacidosis and cerebral edema. Curr Opin Pediatr 2002;14:287–91. 10.1097/00008480-200206000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser N. Cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. Curr Diab Rep 2001;1:41–6. 10.1007/s11892-001-0009-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muir AB, Quisling RG, Yang MCK, et al. Cerebral edema in childhood diabetic ketoacidosis: natural history, radiographic findings, and early identification. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1541–6. 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenbloom AL. Intracerebral crises during treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes Care 1990;13:22–33. 10.2337/diacare.13.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roe TF, Crawford TO, Huff KR, et al. Brain infarction in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. J Diabetes Complications 1996;10:100–8. 10.1016/1056-8727(94)00058-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrot A, Huisman TA, Poretti A. Neuroimaging findings in acute pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. Neuroradiol J 2016;29:317–22. 10.1177/1971400916665389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bialo SR, Agrawal S, Boney CM, et al. Rare complications of pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Diabetes 2015;6:167–74. 10.4239/wjd.v6.i1.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster JR, Morrison G, Fraser DD. Diabetic ketoacidosis-associated stroke in children and youth. Stroke Res Treat 2011;2011:1–12. 10.4061/2011/219706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]