Abstract

Gender refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviours, expressions and identities of girls, women, boys, men and gender diverse people. Gender-related factors are seldom assessed as determinants of health outcomes, despite their powerful contribution. The Gender Outcomes INternational Group: to Further Well-being Development (GOING-FWD) project developed a standard five-step methodology applicable to retrospectively identify gender-related factors and assess their relationship to outcomes across selected cohorts of non-communicable chronic diseases from Austria, Canada, Spain, Sweden. Step 1 (identification of gender-related variables): Based on the gender framework of the Women Health Research Network (ie, identity, role, relations and institutionalised gender), and available literature for a certain disease, an optimal ‘wish-list’ of gender-related variables was created and discussed by experts. Step 2 (definition of outcomes): Data dictionaries were screened for clinical and patient-relevant outcomes, using the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement framework. Step 3 (building of feasible final list): a cross-validation between variables per database and the ‘wish-list’ was performed. Step 4 (retrospective data harmonisation): The harmonisation potential of variables was evaluated. Step 5 (definition of data structure and analysis): The following analytic strategies were identified: (1) local analysis of data not transferable followed by a meta-analysis combining study-level estimates; (2) centrally performed federated analysis of data, with the individual-level participant data remaining on local servers; (3) synthesising the data locally and performing a pooled analysis on the synthetic data and (4) central analysis of pooled transferable data. The application of the GOING-FWD multistep approach can help guide investigators to analyse gender and its impact on outcomes in previously collected data.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, health policies and all other topics, cohort study

Summary box.

The Gender Outcomes INternational Group: to Further Well-being Development (GOING-FWD) framework is a feasible 5-step methodology to assess the impact of gender domains on clinical and patient-relevant outcomes in retrospective studies, allowing a cross-countries comparison.

A multidisciplinary international team (ie, specialists in life science, social science and computer science; patient partners) built the methodology, guaranteeing that the interests of all stakeholders be (were?) represented.

The lack of a standardised definition of gender and data accessibility/protection issues are expected obstacles to the applicability of GOING-FWD methodology.

Strategies to minimise potential drawbacks of the methodology are provided such as the derived ‘wish list’ of gender-related factors or the application of privacy-enhancing technologies including tools for federated analysis.

Introduction

The distinction between sex and gender, which is clear and common in social sciences, has largely been neglected in health sciences. Indeed, sex and gender are often erroneously used and/or measured interchangeably. Given that sex and gender are not independent of each other, solely assessing one or the other cannot account for identified variations in health.1 2 Furthermore, although the reasons explaining the increasing incidence of chronic diseases are incompletely understood, changing family, social, institutional roles and attitudes of men and women in the last decades ultimately play a role. Thus, a wide range of behavioural factors, psychosocial processes, personal, cultural and societal factors can create, suppress or amplify underlying biological health differences.3 4While differences in health status and outcomes have been attributed to biological sex, it is now increasingly recognised that both sex and gender influence the risk of developing certain diseases, presentation of symptoms, severity of illness, response to drugs or non-pharmacological interventions and seeking care behaviours.5 More importantly, gender may also have a bearing on people’s access to and uptake of health services and the resulting health outcomes experienced throughout the life-course.6 Consequently, it is now understood that the intersectionality of gender with other social factors such as race, age, ethnicity, culture and sexual orientation, plays a central role in an individual’s health. The integration of a gender-based framework in health research is a crucial and long-awaited development.7

When considering gender aspects in the evaluation of clinical outcomes, the first challenge for scientists originates from the apparent lack of standardised method to measure the complexities that gender encompasses. Recently, through a Pan-Canadian collaboration of a multidisciplinary team of scientists, a comprehensive list of gender-related variables was established and collected in the setting of premature cardiovascular disease. Constructed with the aim of exploring the impact of gender on the clinical outcomes of young patients with acute coronary syndrome, the Gender and Sex Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease: From Bench to Beyond Gender Score (GPGS) was developed.8 9 The GPGS measures a comprehensive group of gender-related factors and offers a pragmatic means to prospectively explore the relationships between sex, gender and health outcomes. In patients with premature and established cardiovascular disease, gender factors, independent of biological sex, emerged as powerful predictors of the acquisition of risk factors as well as of 1-year adverse health outcomes.9 10 Most significantly, regardless of sex, patients who exhibited gender factors most traditionally ascribed to women’s identity and roles in society were more likely to have a recurrent cardiac event within the first year. While these results have important direct implications for expanding the measurement of gender determinants of health to other populations, they may also identify novel determinants of healthcare costs that could be averted.

To facilitate the integration of sex and gender-based analyses, we developed a standard methodology that can be applied to retrospective studies for testing the associations of gender-related factors with clinical and patient-relevant outcomes.

About the Gender Outcomes INternational Group: to Further Well-being Development (GOING-FWD) integration of gender dimensions into health outcomes research

The Gender Outcomes INternational Group: to Further Well-being Development (GOING-FWD) is a personalised medicine project that explores the effect of sex and gender on outcomes across already available datasets using feasible approaches to perform both traditional and machine-learning-based analytics. It was recently cofunded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and GENDER-NET plus, which is a part of the European EU H2020 initiative (http://gender-net-plus.eu/joint-call/funded-projects/going-fwd/).

For the GOING-FWD project, around thirty accessible databases of observational studies and registries that include non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) among a four-country transatlantic network (ie, Austria, Canada, Spain and Sweden) were identified. The overarching aims of the GOING-FWD project were (1) to integrate sex and gender dimensions in applied health research and (2) to evaluate their impact on clinical cost-sensitive outcomes and patient-reported outcomes related to quality of life in NCDs including cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and neurodegenerative disease. Each partner of the Consortium provided the data dictionary of the retrospective cohort studies conducted in their respective countries.

The GOING-FWD Consortium is composed of investigators with multidisciplinary expertise in gender dimension, psychosocial science, computer science, epidemiology, endocrinology, internal medicine, renal and cardiovascular medicine, reproductive health, neuroscience, preclinical and clinical experimental research, health outcome research, nursing and biostatistics. The investigators were assigned to one of the three-work packages. The GOING-FWD methodology proposed therein is the result of the integrated activities carried out by the GOING-FWD investigators from March 2019 to December 2019. A five-step procedure was developed that can be applied to pre-existing observational cohorts for the integration of gender-related factors in assessing their association with selected health outcomes.

GOING-FWD also has a patient partner advocate group. All interactions with patient partners are based on inclusiveness, support, mutual respect and cobuilding. For example, patient partners can assist in knowledge dissemination (eg, summer institutes, online educational materials, trainee journal club meetings, public forum presentations, may coauthor manuscripts and provide feedback on draft manuscripts during development and participate in teleconferences. A patient partner representative also attends monthly GOING-FWD steering meetings.

The GOING-FWD roadmap for already collected data

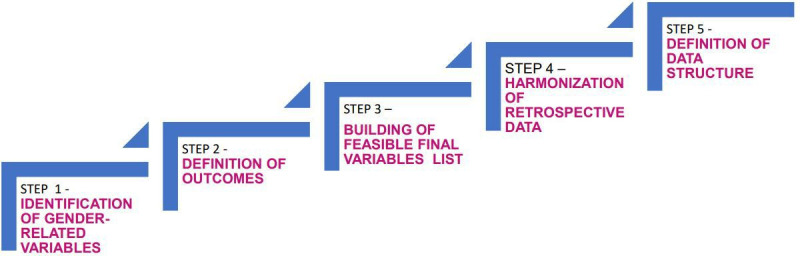

A multistep methodology was developed as summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The GOING-FWD multistep methodology on identification and inclusion of gender factors in retrospective cohort studies. GOING-FWD, Gender Outcomes INternational Group: to Further Well-being Development.

Step 1: identification of gender-related variables

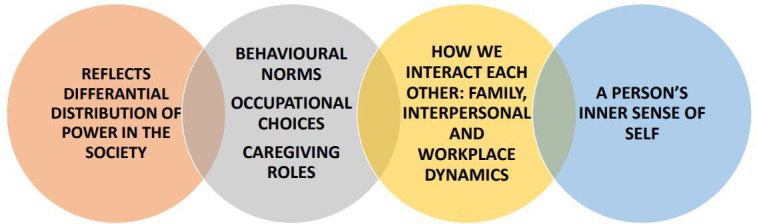

Based on the data dictionaries provided by all participating centres, a preliminary list of the gender-related factors available in selected datasets was compiled by the coordinating centre. The template including the identified sex and gendered factors was presented and discussed at the first consortium meeting (Montréal, April 2019) by all investigators and stakeholders. Guided by the gender framework of the Women Health Research Network (ie, gender identity, gender role, gender relations and institutionalised gender)11 (figure 2), and available literature in the four NCDs areas, the investigators created an optimal ‘wish list’ of gender-related variables/factors: the definitions and validity of the proposed variables were discussed and expert consensus reached.

Figure 2.

Domains that gender encompasses.

Investigators considered variables that differ between men and women in terms of prevalence and/or identified (in the published literature) as exerting different effects on the outcomes of men and women as ‘gender-related’ variables. A revised draft template including additional gendered variables was created (table 1).

Table 1.

GOING-FWD cohorts gender related variables—wish list

| Roles | Institutionalised gender |

| Primary earner status | Educational Level |

| Employment Status | SES/Income |

| Occupation | Monthly finances |

| Paid work hours per week | Income (personal, household) |

| Unpaid work hours per week (eg, caregiver hours) | No of persons living in household |

| Full/part time work | Retirement eligibilities |

| Child caregiver responsibilities the individual or others | Perceived Social Standing Questionnaire (eg, McArthur Scale) |

| Adult caregiver responsibilities | GII Questionnaire |

| No of hours per week spent on housework | Maternity paternity-related variables |

| Status of household’s primary responsibility | Discrimination |

| No of children | Day-to-day experiences |

| Relations | Perceived bias |

| Marital/relationship status | Stigmatisation |

| Family or local network (social capital) | Violence (hx or present) |

| Social support | Intimate partner domestic |

| Social support (any recognised social support instrument) | Ethnic violence |

| Availability of caretaker (for self) | Sexual orientation |

| Identity | Immigration status |

| Stress | Behavioural/lifestyle risk factors |

| 14-Item Perceived Stress Scale | European Health Determinants Module |

| Stress level at work (any measure of stress) | Current smoking, smoking history, cigarettes per day |

| Stress level at home (any measure of stress) | Physical activity |

| Stress management | Physical activity (eg, self-reported: PPAQ) - Physical activity (eg, accelerometer) |

| Personality traits | Food diary - Diet quality index |

| Emotional intelligence Questionnaire | Alcohol consumption |

| Any validated measures of personality (NEO classic five personality traits) |

Substance use (use of drugs) |

| BSRI (instrument) measurement of gender identity | Nutrition |

| Depressive symptomatology/anxiety | Overall diet quality index |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 | Physical activity barriers (fatigue, lack of motivation, etc) |

| HAD Scale | Nutrition barriers (expensiveness, lack of motivation, etc) |

| Anxiety/depression any scale | Physical activity facilitators (social support, self-motivation, etc) |

| Childhood trauma (reported history) | Nutrition facilitators (social support, self-motivation, etc) |

BSRI, Bem Sex-Role Inventory; GII, Gender Inequality Index; GOING-FWD, Gender Outcomes INternational Group: to Further Well-being Development; HAD, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; hx, history; NEO, Neuroticism, Extroversion, Openness; PPAQ, Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire; SES, socioeconomic status.

Step 2: definition of outcomes

Each of the cohort data dictionaries was screened for outcomes of interest (including clinical/survival and patient-reported outcomes) by the coordinating centre. Similar to gendered variables, a second working group was tasked with developing a list of outcome variables, using the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement (ICHOM) framework12 [The ICHOM Standard Sets are standardised outcomes, measurement tools, time points and risk adjustment factors for a given condition (eg, CKD, diabetes, etc). Developed by a consortium of experts and patients in the field of outcomes research, the ICHOM Standard Sets focus on clinical and patient-centred outcomes. By creating a standardised list of the outcomes based on the patient’s priorities, the ICHOM framework ensures that the patient remains at the centre of care] and cost-sensitive variables and/or patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) collected in all databases as the basic ‘outcomes variable list’. A prespecified list of potential outcomes was created by all GOING-FWD investigators.

Depending on the study population and type of dataset (eg, administrative, observational cohort study), we identified as relevant the following cost-sensitive outcomes: (1) inpatient outcomes including: in-hospital length of stay, in-hospital complications and/or death and readmission within 30 days of discharge; (2) outpatient outcomes including: access and/or numbers of visits and procedures, admissions, death, progression of disease and disability. We also looked for the availability of any PROMs, including symptoms (eg, pain), functioning, health related quality of life, depression and stress. The ICHOM specific-disease outcomes were considered for each of the four main clinical areas of interest. The revised draft template with outcomes, compiled by the investigators, was discussed and approved by all (table 2).

Table 2.

GOING-FWD cost-sensitive and patient-relevant outcomes measures—wish list

| Condition | Survival | Acute complications | Patient-reported health status | Disease progression | Disease-specific outcomes | Medications |

| Acute coronary syndrome | All-cause mortality | Major procedural complications | SAQ-7 PHQ-2 |

Revascularisation Hospitalisation |

MI HF Stroke |

Beta-blockers ACEi/ARB Statin Antiplatelet |

| Heart failure | All-cause mortality | Treatment side effects/ complications | KCCQ | Hospitalisation | Beta-blockers ACEi/ARB MRAs ARNi |

|

| Stroke | All-cause mortality | Intracranial haemorrhage | Cognitive function Motor function Social function PROMIS SF V.1.1 Global Health |

Hospitalisation | Stroke recurrence | |

| Dementia | All-cause mortality | NPI MoCA EQ-5D Bristol Activity Daily Living Scale QoL-AD Quality of Well-being Scale |

Clinical Dementia Rating Hospitalisation Falls |

|||

| Parkinson’s | All-cause mortality | PDQ-8 | Hospitalisation Falls |

|||

| Multiple Sclerosis | All-cause mortality | Relapse motor/sensory function |

||||

| Endocrine/ Diabetes |

All-cause mortality | Ketoacidosis Hypoglycaemic/ hyperglycaemic |

WHO-5 PAID PHQ-9 |

Physician visits Hospitalisation |

Microvascular/microvascular complications | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | All-cause mortality | Access bleeding Access hematoma Access infection Line sepsis Catheter-related infections herniation/effusion |

SF-12 or SF-36 PROMIS-Global Health or WHO-5 Global Health PROMIS-29 EQ-5D-L PGI |

Hospitalisation eGFR Transplant Dialysis Microalbuminuria Kidney Failure Risk Index Stage 5 |

CV events: HF, stroke, MI, PAD Peritoneal dialysis modality survival/vascular access survival Graft failure |

Activated vitamin D Erythropoietin Calcitonin phosphate binders Potassium binders Insulin Statins MRAs ACEi/ARB Beta-blockers Diuretics |

ACEi, ACE inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNi, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life questionnaire-5D; HF, heart failure; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MI, myocardial infarction; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MRA, mineralcorticoid receptor antagonist; NPI, neuropsychiatric inventory; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PAID, Problem Areas in Diabetes Questionnaire; PDQ-8, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-8; PGI, Patient Global Impression Scales; PHQ-2, Public Health Questionnaire-2; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PROMIS-Global Health, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PROMIS-SF, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Form; QoL-AD, Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease questionnaire; SAQ-7, Seattle Angina Questionnaire-7; SF-12/16, 12/16 item Short Form survey; WHO-5, WHO-5 Well-Being Index.

Step 3: building of feasible final list

The two lists were sent to each participating centre to rescreen their datasets for the presence of the identified sex- and gender-related as well as outcome variables. A cross-validation between gender-related and outcomes variables available per database was performed both locally and centrally. In case of disagreement or discordant definitions of variables among the wish-list and the actual-list, a discussion to reach consensus between coordinator centre and local principal investigators was performed. In principle, a more inclusive approach was pursued for both gender-related variables and outcomes definition.

After the double check of wish-list and local actual-list, the final feasible list of variables (core dictionary) was built, and each country partner used the lists to apply to their respective research ethics boards according to the country regulations.

Step 4: retrospective data harmonisation

Once the final list was compiled, the harmonisation potential of gender-related and outcomes variables was assessed using the Maelström Research guidelines for rigorous retrospective data harmonisation and merging when possible13 (Core Dataset).

The harmonisation across the different databases is a premise for assessing the feasibility of big data analysis, as well as minimising deviations in data measurement across independently recruited databases. Data harmonisation methodology consists of assessing the presence and definitions of common variables across the different databases, followed by the creation of a harmonised dataset and subsequent extraction of information from study-specific datasets into the harmonised dataset. For example, while many datasets may record smoking status, the exact definition of this variable may differ between datasets: one may define this variable as dichotomous, others may quantify the number of cigarettes smoked by the participant. Through data harmonisation, a new variable definition is created to include the information from each of these datasets, which in this case would be reduced to smoking status as a dichotomous variable. Throughout this process, harmonised definitions that are created are scrutinised until a consensus is reached.

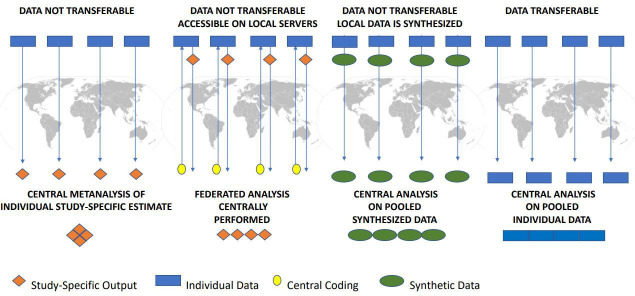

Step 5: definition of data structure

Beyond harmonisation, the structure and country-specific management of health data was recognised as crucial to planning and conducting the final analysis addressing the relationships between the gender-related factors. The analysis plans for each country will be based on the following options: (1) if data are not transferable even when anonymised—study-specific data analyses will be done locally followed by a meta-analysis combining study-level estimates; (2) for multiple cohorts in different countries, analyses will be done centrally, but the individual-level participant data will remain on local servers using a federated analysis approach; (3) the local data are synthesised and then a pooled analysis of the synthesised data is performed or (4) if the data are transferable: data will be pooled and analysed at a central location (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Data structure and potential options for analysis based on transferability of data.

Strengths and limitations of the GOING-FWD methodology

The GOING-FWD methodology is a multistep process that provides insights on how to identify gender-related factors when variables have already been collected through the merging of several datasets and how to design the analysis plan on the core dataset. The multidimensionality of gender aspects might be effectively captured due to its complexity by non-traditional analytic approaches. The Big Data paradigm shift is significantly transforming healthcare and biomedical research.14 Massive volumes of aggregated biomedical data often display different levels of granularity fostering the capability to explore, on large international scales, the effect of variables such as gender and/or sex. Big data allows researchers to overcome sample size issues and perform types of analysis such as interaction or mediation that would not be feasible and reliable in small cohorts/studies. Nevertheless, there are some important issues related to data privacy and the merging of different databases when a cross-country comparison is planned, especially where issues on general data protection regulation need to be addressed in detail. Of note, the GOING-FWD challenges in ensuring data privacy and protection have foster our effort to develop techniques like synthetic data to make amalgamation of data possible.

Strengths

The GOING-FWD framework is a feasible methodology to foster the assessment of the gender impact on outcomes in retrospective studies. The screening of each dataset is a step that not only allows to identify the gender-related variables but also provides the rationale for selecting psycho-social factors that could be collected prospectively in the same cohort. The effort of investigating how sex and gender-related factors impact clinical and patient-related outcomes in NCDs is essential as it provides evidence for sex-tailored and gender-tailored interventions.

We have learnt that a multidisciplinary team is a prerequisite for developing such methodology including gender experts and patient partners. Patients with lived experience can contribute to understanding what is really important for a specific disease which further strengthens the concept of patient empowerment in clinical practice.

The international nature of GOING-FWD methodology highlights important considerations on the complexity of gender. Gender norms, identities and relations vary by culture, historical era, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographical location and other factors. We expect that the gender behaviours and attitudes captured by our variables may differ among women, men, and gender diverse individuals as well as between these groups. Gender norms also change overtime and across countries. Furthermore, everyone over time can be exposed to different degree of any gender-related factors. Impactful findings generated by retrospective analyses ca stimulate the scientific community to conduct a prospective collection on gender-factors in the design of future studies. Therefore, as researchers, we need to recognise the dynamic nature of integrating gender in clinical research questions and act accordingly. We also envisioned our multicountry analyses as an opportunity to capture institutional gender by including some country specific variables that are commonly available like the Gender Inequality Index (GII) developed by the United Nations Development Programme.15 The GII is a composite measure to quantify gender inequality within a country and measures opportunity costs, reproductive health empowerment and labour market participation. Another similar measure of gender is the European Institute for Gender Equality’s Gender Equality Index, which includes additional details about country specific domains of health, violence against women, work, money, knowledge time and power.16 The idea is to relook and rethink on how we can gain the most from data on gender that are already available.

Finally, the GOING-FWD approach is timely and might foster inclusion of gender in understanding the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, the global COVID-19 economic and medical crisis could be the first outbreak where sex and gender differences are recorded and taken into account by researchers and policy makers. The GOING-FWD methodology will be instrumental in exploring the impact of various gender domains on outcomes across countries.

Challenges

In developing the GOING-FWD methodology, we have faced practical challenges. First, the lack of a standardised definition of gender-related factors is perceived as an obstacle to researchers even if they are interested in the topic. The low availability of gender-related factors in retrospective studies is not surprising but this should not preclude analyses. We strongly encourage clinical and even preclinical researchers to start from what they have even if only one gender-related factor is available. Merging more datasets allows us to perform analyses that incorporate interaction and mediation given large sample sizes. Second, in the current era, data accessibility and data protection issues in international networks can represent a deal breaker in pursuing this kind of research approach. Increasingly strict data protection regulations in many jurisdictions limit the ability to share sensitive health information. This requires the application of privacy enhancing technologies to enable the necessary analyses to be performed without the transfer of personal health information. Finally, harmonisation is a necessary step to allow big data analysis, but it is a time - consuming process and susceptible to pitfalls related to the quality of the process and difficulties of maintenance when several databases from different countries are merged. Personnel with explicit knowledge and skills are required to perform data harmonisation from both technical (ie, computing science, mathematics) and clinical (ie, life science) perspectives.

We believe that our example of a derived ‘wish list’” based on selected variables offers a standardised tool that can be widely used to explore the consistency of associations with health behaviours and outcomes.

Perspective and significance

The GOING-FWD Consortium, a multidisciplinary network of Canadians and European researchers and patient partners, provides a framework that will support clinical researchers in integrating gender relevant factors in their research questions when using already collected databases hence providing solutions for the challenges that such approach poses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the application of a systematic multistep approach defining gender-related variables, the use of data harmonisation and country-specific data structure models, inform the identification and inclusion of gender factors in retrospective cohort studies. Gleaning important information on gender will not only strengthen current clinical practice but will also provide a stepping—stone for sex-tailored and gender-tailored interventions and care.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Collaborators: GOING‑FWD Collaborators: Karin H. Humphries; Monica Parry; Ruth Sapir-Pichhadze; Michal Abrahamowicz; Simon Bacon; Peter Klimek; Jennifer Fishman, Vera Regitz-Zagrosek; Londa Schiebinger; Carole Clair; Rachel P. Dryer; Christina P. Tadiri; Zahra Azizi; Rubee Dev; Pouria Alipour; Uri Bender; Sabeena Jalal; Alexia Della Vecchia; Jovana Stojanovic; Salima Hemani; Heather Burnside; Carola Deschinger; Juergen Harreiter; Simon D. Lindner; Teresa Gisinger; Giulia Tosti; Claudia Tucci; Giulio F. Romiti; Agnė Laučytė-Cibulskiene; Liam Ward; Leah Muñoz; Raquel Gomez De Leon; Ana Maria Lucas; Sonia Gayoso; Raúl Nieto; Maria Sanchez; Sandra Amador; Cristina Rochel; Donna Hart; Nicole Hartman/Nickerson; Angie Fullerton/MacCaul; Jeanette Smith; Myra Lefkowitz; Ann Keir; Kyle Warkentin; Rachael Manion.

GOING‑FWD Co-Principal Investigators: Louise Pilote, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Colleen M. Norris, University of Alberta, Canada; Valeria Raparelli, University of Ferrara, Italy.

GOING‑FWD Site Principal Investigators: Alexandra Kautzky-Willer, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Karolina Kublickiene, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden; Maria Trinidad Herrero, Universidad de Murcia, Spain.

GOING-FWD Co-Investigators: Karin H. Humphries, University of British Columbia, Canada; Monica Parry, Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, Canada; Ruth Sapir-Pichhadze, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Michal Abrahamowicz, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Khaled El Emam, University of Ottawa, Canada; Simon Bacon, Concordia University, Canada; Peter Klimek, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Jennifer Fishman, McGill University, Canada.

GOING-FWD Scientific Advisory Committee: Vera Regitz-Zagrosek, Charité, University Medicine Berlin, German and University Hospital Zürich, University of Zürich, Switzerland; Londa Schiebinger, Stanford University, USA; Carole Clair, University of Lausanne, Switzerland; Rachel P. Dryer, Yale University, USA.

GOING‑FWD Early Career Researchers: Christina P. Tadiri, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Zahra Azizi, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Rubee Dev, University of Alberta, Faculty of Nursing, Canada; Pouria Alipour, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Uri Bender, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Sabeena Jalal, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Alexia Della Vecchia, McGill University Health Center and McGill University, Canada; Jovana Stojanovic, Concordia University, Canada; Salima Hemani, Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, Canada; Heather Burnside, Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, Canada; Carola Deschinger, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Juergen Harreiter, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Simon D. Lindner, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Teresa Gisinger, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Giulia Tosti, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy; Claudia Tucci, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy; Giulio Francesco Romiti, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy; Agnė Laučytė-Cibulskiene, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden; Liam Ward, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden; Leah Muñoz, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden; Raquel Gomez De Leon, Universidad de Murcia, Spain; Ana Maria Lucas, Universidad de Murcia, Spain; Sonia Gayoso, Universidad de Murcia, Spain; Raúl Nieto, Universidad de Murcia, Spain; Maria Sanchez, Universidad de Murcia, Spain; Sandra Amador, Universidad de Murcia, Spain; Cristina Rochel, Universidad de Murcia, Spain.

GOING‑FWD Patient Partners: Donna Hart, Ontario, Canada; Nicole Hartman/Nickerson, Nova Scotia, Canada; Angie Fullerton/MacCaul, Prince Edward Island, Canada; Jeanette Smith, Ontario, Canada; Myra Lefkowitz, Ontario, Canada; Ann Keir, British Columbia, Canada; Kyle Warkentin (caregiver), British Columbia, Canada; Rachael Manion, Ontario, Canada.

Contributors: VR: conception, design, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and revision; CMN: conception, design, interpretation of data, critical revision; UB: acquisition and analysis; MTH, design, interpretation of data, revision of the draft; AKW: design, interpretation of data, revision of the draft; KK: design, interpretation of data, revision of the draft; KEE: analysis and development of new IT solution, synthetic data; LP: conception, design, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and revision; GOING-FWD Consortium: design contribution, acquisition of data and revision of the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The GOING-FWD Consortium is funded by the GENDER-NET Plus ERA-NET Initiative (Project Ref. Number: GNP-78): The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (GNP-161904), La Caixa Foundation (LCF/PR/DE18/52010001), The Swedish Research Council (2018-00932) and The Austrian Science Fund (FWF, I 4209). VR was funded by the Scientific Independence of Young Researcher Program of the Italian Ministry of University, Education and Research (RBSI14HNVT).

Competing interests: VR, CNM, UB, MTH, AKW, KK, and LP have nothing to disclose; KEE is co-founder, director, and investor in Replica Analytics Ltd, a CHEO Research Institute / University of Ottawa spinoff company that develops data synthesis software.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

GOING‑FWD Collaborators:

Karin H Humphries, Monica Parry, Ruth Sapir-Pichhadze, Michal Abrahamowicz, Simon Bacon, Peter Klimek, Jennifer Fishman, Carole Clair, Rachel P. Dryer, Christina P. Tadiri, Zahra Azizi, Rubee Dev, Pouria Alipour, Sabeena Jalal, Alexia Della Vecchia, Jovana Stojanovic, Salima Hemani, Heather Burnside, Carola Deschinger, Juergen Harreiter, Simon D. Lindner, Teresa Gisinger, Giulia Tosti, Claudia Tucci, Giulio Francesco Romiti, Agne Laučytė-Cibulskiene, Liam Ward, Leah Muñoz, Raquel Gomez De Leon, Ana Maria Lucas, Sonia Gayoso, Raúl Nieto, Maria Sanchez, Sandra Amador, Cristina Rochel, Donna Hart, Nicole Hartman/Nickerson, Angie Fullerton/MacCaul, Jeanette Smith, Myra Lefkowitz, Ann Keir, Kyle Warkentin, Rachael Manion, Vera Regitz-Zagrosek, and Londa Schiebinger

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the project was obtained from the coordinator centre at McGill University, Canada (2020–5452).

References

- 1. CIHR, Online Training Modules . Integrating Sex & Gender in Health Research, 2019. Available: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/49347.html [Accessed 23 Apr 2020].

- 2. Norris CM, Murray JW, Triplett LS, et al. Gender roles in persistent sex differences in health-related quality-of-life outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease. Gend Med 2010;7:330–9. 10.1016/j.genm.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weber AM, Cislaghi B, Meausoone V, et al. Gender norms and health: insights from global survey data. Lancet 2019;393:2455–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30765-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4., Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, et al. , GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:2287–323. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartz D, Chitnis T, Kaiser UB, et al. Clinical advances in sex- and Gender-Informed medicine to improve the health of all: a review. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:574–83. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vaidya V, Partha G, Karmakar M. Gender differences in utilization of preventive care services in the United States. J Womens Health 2012;21:140–5. 10.1089/jwh.2011.2876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tannenbaum C, Ellis RP, Eyssel F, et al. Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering. Nature 2019;575:137–46. 10.1038/s41586-019-1657-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pelletier R, Ditto B, Pilote L. A composite measure of gender and its association with risk factors in patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. Psychosom Med 2015;77:517–26. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pelletier R, Khan NA, Cox J, et al. Sex versus gender-related characteristics: which predicts outcome after acute coronary syndrome in the young? J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:127–35. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norris CM, Johnson NL, Hardwicke-Brown E, et al. The contribution of gender to apparent sex differences in health status among patients with coronary artery disease. J Womens Health 2017;26:50–7. 10.1089/jwh.2016.5744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson JL, Greaves L, Repta R. Better science with sex and gender: facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. Int J Equity Health 2009;8:14. 10.1186/1475-9276-8-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. International Consortium for health outcomes measurement, 2020. Available: https://www.ichom.org/ [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- 13. Fortier I, Raina P, Van den Heuvel ER, et al. Maelstrom research guidelines for rigorous retrospective data harmonization. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:103–5. 10.1093/ije/dyw075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Obermeyer Z, Emanuel EJ. Predicting the Future - Big Data, Machine Learning, and Clinical Medicine. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1216–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1606181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gender inequality index (GII), 2020. Available: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-inequality-index-gii [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- 16. Gender equality index, 2020. Available: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2019 [Accessed 22 May 2020].