Abstract

Background

Lumbar disc degeneration (LDD) is an essential pathological mechanism related to low back pain. Current research on spinal surgery focused on the sophisticated mechanisms involved in LDD, and autophagy was regarded as an essential factor in the pathogenesis.

Objectives

Our research aimed to apply a bioinformatics approach to select some candidate genes and signaling pathways in relationship with autophagy and LDD and to figure out potential agents targeting autophagy- and LDD-related genes.

Materials and methods

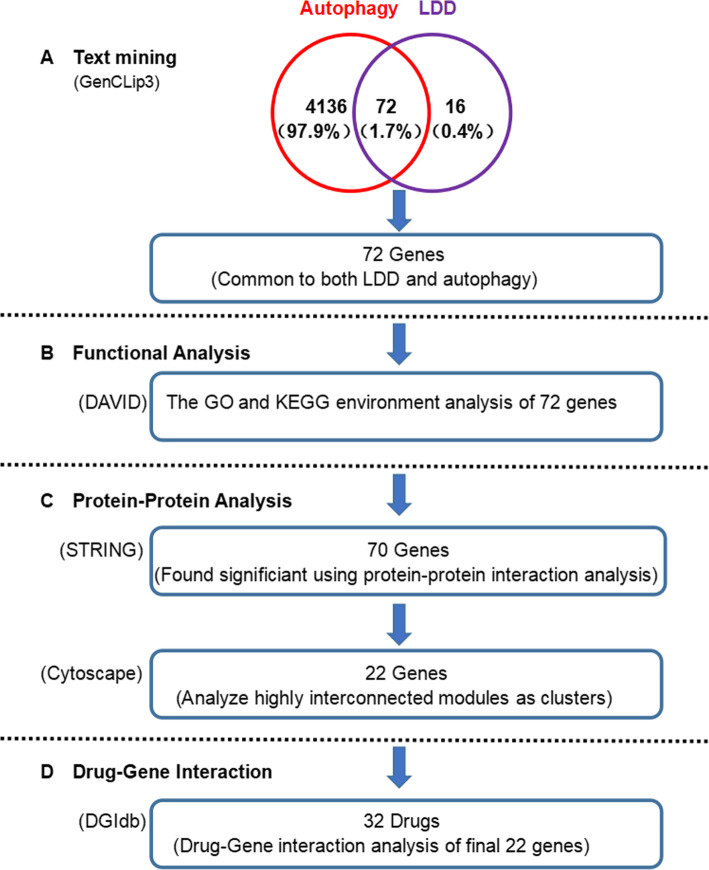

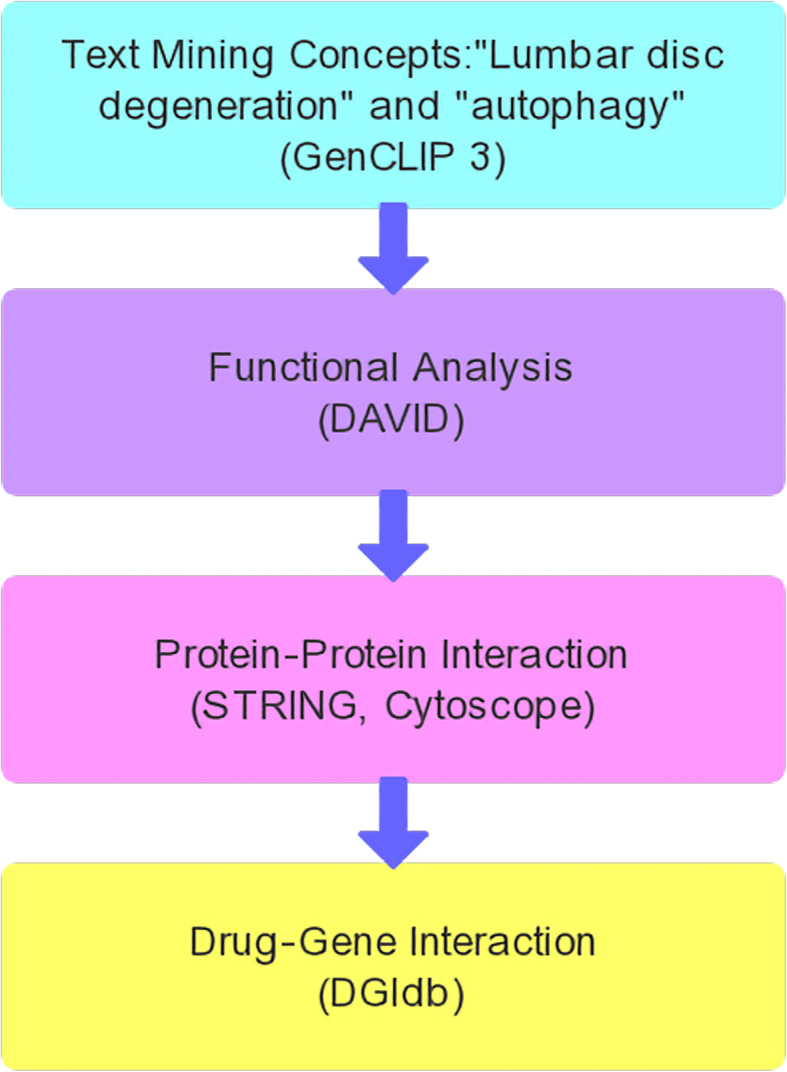

Text mining was used to find autophagy- and LDD-related genes. The DAVID program was applied in Gene Ontology and pathway analysis after selecting these genes. Several important gene modules were obtained by establishing a network of protein-protein interaction and a functional enrichment analysis. Finally, the selected genes were searched in the drug database to find the agents that target LDD- and autophagy-related genes.

Results

There were 72 genes related to “autophagy” and “LDD.” Three significant gene modules (22 genes) were selected by using gene enrichment analysis, which represented 4 signaling pathways targeted by 32 kinds of drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The interactions between drugs and the genes were also identified.

Conclusion

To conclude, a method was proposed in our research to find candidate genes, pathways, and drugs which were involved in autophagy and LDD. We discovered 22 genes, 4 pathways, and 32 potential agents, which provided a theoretical basis and new direction for clinical and basic research on LDD.

Keywords: Bioinformatics-based analysis, Targeting drug, Autophagy, Gene, Lumbar disc degeneration, Pathway

Introduction

For low back pain, lumbar disc degeneration (LDD) is an essential pathological mechanism involved [1]. According to the previous studies, lumbar degenerative conditions including lumbar instability and stenosis as well as disc herniation lumbar stenosis often occur following LDD [2, 3]. Multiple factors may contribute to LDD, including nutrition, injury, spinal biomechanics, inflammation, and biology [4, 5]. Recent studies on spinal surgery mainly focused on the sophisticated mechanisms related to LDD [6], and autophagy was regarded as an essential pathological factor.

Autophagy is an intracellular catabolic process dependent on lysosome which involves the degradation of protein aggregates, organelles, and cytoplasmic proteins. Pathologically enhanced autophagy was considered to be related to cell death in certain scenarios; however, it plays a protective role in various circumstances [7].

In the past decade, multiple studies on gene expression profiling worked on autophagy and LDD, with piles of candidate genes identified [8, 9]. The purpose of our research was to find candidate genes and signaling pathways in relationship with autophagy and LDD by using a bioinformatics approach and to discover drugs that target LDD- and autophagy-related genes. Firstly, through text mining, we detected the genes associated with autophagy and LDD. Subsequently, the online bioinformatics resource DAVID was used to perform signaling pathway and functional analyses. Then, protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were established by using the genes both related to autophagy and LDD, with 3 important gene modules identified. Finally, candidate drugs were identified according to the gene-drug interaction analysis by using the selected genes. Through this method, we determined some potential key genes, signaling pathways, and drugs, which provide new insights for clinical and basic research on LDD.

Materials and methods

Text mining

Text mining was conducted by using the GenCLip3 platform (http://ci.smu.edu.cn/genclip3/analysis.php). The names of all genes available in the published reports associated with the concept of the search were collected by using GenCLip3 [10]. LDD and autophagy were respectively searched, and the genes related to both autophagy and LDD were selected for further analysis.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and pathway analysis

In Gene Ontology enrichment analysis [11], gene products were depicted according to the following 3 parts: cellular component(CC), molecular function (MF), and biological process (BP). Data resources of available metabolic pathways were collected from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [12]. Genes related to both terms were selected by using the DAVID [13] for further GO and KEGG enrichment. P <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

PPI networks and module analysis

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, version 11.0) [14] database was applied to establish a network of protein-protein interaction of the genes related to both autophagy and LDD. The significant threshold was set as interaction value >0.900 (the highest reliability). PPI networks were then established by applying the Cytoscape software [15]. The molecular complex detection (MCODE) is an automatic approach for analyzing highly associated modules as molecular clusters or complexes.

The interaction between drugs and genes

The Drug Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb, http://www.dgidb.org) was used to reveal the interactions between drugs and the selected genes [16]. Potential drugs targeting the genes related to autophagy and LDD could provide new insight into therapeutic strategies.

Results

Results of text mining

According to the mining strategy shown in Fig. 1, 4208 genes were identified associated with autophagy and 88 genes with LDD. There were 72 genes related to both autophagy and LDD (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Overall data mining strategy

Table 1.

Seventy-two genes related to both autophagy and LDD were identified

| ACAN | CASP9 | FASLG | IL6 | MSTN | TIMP1 |

| ADAMTS5 | CCL5 | FGFR1 | IL6ST | NOS2 | TLR4 |

| ADIPOQ | CDKN2A | FGFR3 | LEP | NOS3 | TNF |

| AKT1 | COL1A1 | GSR | LIF | PCBD1 | TNFRSF10A |

| AQP3 | COL2A1 | HSPA8 | MAPK1 | PIK3CA | TNFRSF11B |

| BAX | CSF1 | IGF1 | MIR100 | PPM1D | TNFSF10 |

| BCL2 | CSF1R | IGF1R | MIR146A | PRIMA1 | TP53 |

| BDNF | CTGF | IL10 | MMP1 | PTH | TRPC6 |

| BGLAP | CX3CL1 | IL1A | MMP13 | PTK2B | TRPV4 |

| BMPR2 | CX3CR1 | IL1B | MMP2 | SOX9 | TSLP |

| CALCA | CXCL12 | IL1RN | MMP3 | SPARC | VDR |

| CASP3 | FAS | IL4 | MMP9 | STAT3 | VEGFA |

Fig. 2.

Summary of data mining results

Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis

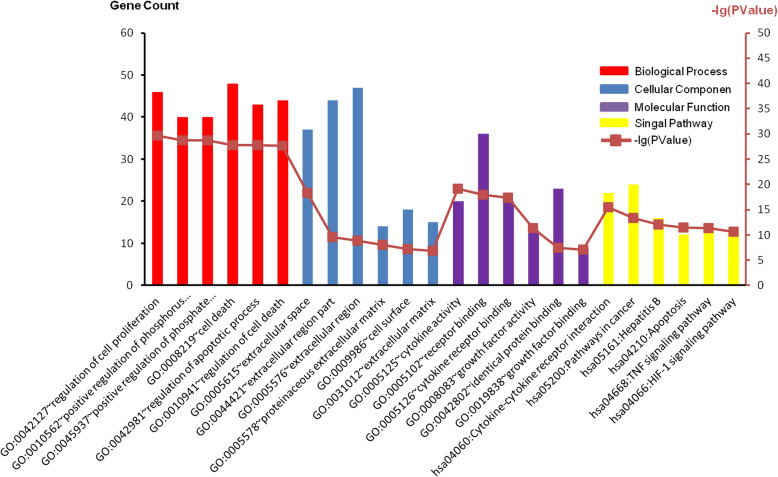

GO and KEGG analyses were performed by using the 72 genes, and P value <0.05 was set as the standard (Fig. 3). In Fig. 3, the top 6 important terms were shown respectively.

Fig. 3.

GO terms and KEGG pathways of the 72 genes related to both autophagy and LDD

Furthermore, the annotation of these genes is presented in Table 2. It was found that in the biological process group, the selected genes were mostly associated with cell proliferation, cellular death and apoptosis, and phosphorus metabolic activities. In the cellular component group, most of the selected genes were in relationship with the extracellular matrix and cell surface. In the molecular function group, the selected genes were associated with the binding with identical protein, the activities of growth factor and cytokine, and the binding with receptors. In the KEGG signaling pathway group, the selected genes were related to the interaction between cytokines and their receptors, HIF-1 and TNF signaling pathways, hepatitis B, apoptosis, and cancer-related pathways.

Table 2.

The top six pathways in GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the 72 genes related to both autophagy and LDD

| Category | Term | Count | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0042127~regulation of cell proliferation | 46 | 2.12E−30 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0010562~positive regulation of phosphorus metabolic process | 40 | 1.70E−29 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0045937~positive regulation of phosphate metabolic process | 40 | 1.70E−29 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0008219~cell death | 48 | 1.79E−28 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0042981~regulation of apoptotic process | 43 | 1.85E−28 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0010941~regulation of cell death | 44 | 2.20E−28 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005615~extracellular space | 37 | 5.19E−19 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0044421~extracellular region part | 44 | 2.75E−10 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005576~extracellular region | 47 | 1.36E−09 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005578~proteinaceous extracellular matrix | 14 | 1.01E−08 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0009986~cell surface | 18 | 5.52E−08 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0031012~extracellular matrix | 15 | 1.25E−07 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005125~cytokine activity | 20 | 7.59E−20 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005102~receptor binding | 36 | 1.05E−18 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005126~cytokine receptor binding | 20 | 3.81E−18 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0008083~growth factor activity | 13 | 5.03E−12 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0042802~identical protein binding | 23 | 3.69E−08 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0019838~growth factor binding | 9 | 8.56E−08 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04060:Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 22 | 3.02E−16 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa05200:Pathways in cancer | 24 | 4.51E−14 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa05161:Hepatitis B | 16 | 8.20E−13 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04210:Apoptosis | 12 | 3.07E−12 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04668:TNF signaling pathway | 14 | 4.18E−12 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04066:HIF-1 signaling pathway | 13 | 2.18E−11 |

GO Gene Ontology, KEGG Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

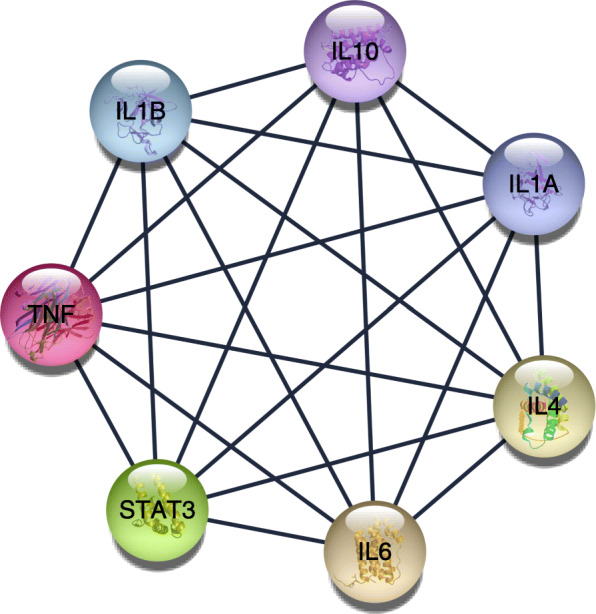

PPI network and module analysis

The STRING website and Cytoscape software were used to analyze the 72 genes. There were 185 edges and 70 nodes/genes with scores >0.900 (highest confidence), and the PPI networks were established (Fig. 4). The MCODE plug-in was used, and 3 pivotal modules were selected. In module 1, there were seven nodes and twenty-one edges (Fig. 5), which were associated with the MAPK signaling pathway, the extracellular space, the binding with cytokine receptors, and the chemokine secretion (Table 3). In module 2, there were twenty-six edges and nine nodes (Fig. 6), which were related to the disassembly of the extracellular matrix, the proteins in the extracellular matrix, the activity of metalloendopeptidase, and the Estrogen signaling pathway (Table 4). In module 3, there were six nodes and eight edges (Fig. 7), which were related to the negative modulation of apoptosis, the complex of transferase, and the transportation of phosphorus-containing groups, MAPK signaling pathway, and the binding with cytokine receptors (Table 5).

Fig. 4.

Based on the STRING online database, 70 genes were filtered into the PPI network

Fig. 5.

The most significant module 1 from the PPI network

Table 3.

Functional and pathway enrichment of module 1 genes

| Category | Term | Count | P value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:1903426~regulation of reactive oxygen species biosynthetic process | 6 | 6.31E−12 | IL4, IL6, TNF, IL1B, IL10, STAT3 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0032642~regulation of chemokine production | 6 | 7.31E−12 | IL4, IL6, TNF, IL1B, IL10, IL1A |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0032602~chemokine production | 6 | 1.04E−11 | IL4, IL6, TNF, IL1B, IL10, IL1A |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005615~extracellular space | 6 | 5.31E−05 | IL4, IL6, TNF, IL1B, IL10, IL1A |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0009897~external side of plasma membrane | 3 | 0.004095871 | IL4, IL6, TNF |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0044421~extracellular region part | 6 | 0.006314367 | IL4, IL6, TNF, IL1B, IL10, IL1A |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005126~cytokine receptor binding | 7 | 2.85E−11 | IL4, IL6, TNF, IL1B, IL10, IL1A, STAT3 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005125~cytokine activity | 6 | 3.44E−09 | IL4, IL6, TNF, IL1B, IL10, IL1A |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0070851~growth factor receptor binding | 5 | 6.61E−08 | IL4, IL6, IL1B, IL10, IL1A |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04630:Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 4 | 1.75E−04 | IL4, IL6, IL10, STAT3 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04668:TNF signaling pathway | 3 | 0.00345185 | IL6, TNF, IL1B |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04010:MAPK signaling pathway | 3 | 0.01832436 | TNF, IL1B, IL1A |

Fig. 6.

The second significant module 2 from the PPI network

Table 4.

Functional and pathway enrichment of module 2 genes

| Category | Term | Count | P value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0022617~extracellular matrix disassembly | 7 | 5.09E−13 | MMP9, ACAN, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1, TIMP1 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0030198~extracellular matrix organization | 8 | 9.66E−12 | MMP9, ACAN, SPARC, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1, TIMP1 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0043062~extracellular structure organization | 8 | 9.86E−12 | MMP9, ACAN, SPARC, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1, TIMP1 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005578~proteinaceous extracellular matrix | 8 | 4.33E−11 | MMP9, ACAN, SPARC, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1, TIMP1 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0031012~extracellular matrix | 8 | 6.42E−10 | MMP9, ACAN, SPARC, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1, TIMP1 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005615~extracellular space | 7 | 2.24E−05 | MMP9, IGF1, SPARC, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, TIMP1 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0004222~metalloendopeptidase activity | 5 | 1.84E−07 | MMP9, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0008237~metallopeptidase activity | 5 | 1.48E−06 | MMP9, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0004252~serine-type endopeptidase activity | 5 | 4.78E−06 | MMP9, MMP3, MMP13, MMP2, MMP1 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04066:HIF-1 signaling pathway | 2 | 0.067876196 | IGF1, TIMP1 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04915:Estrogen signaling pathway | 2 | 0.069936289 | MMP9, MMP2 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04668:TNF signaling pathway | 2 | 0.075412069 | MMP9, MMP3 |

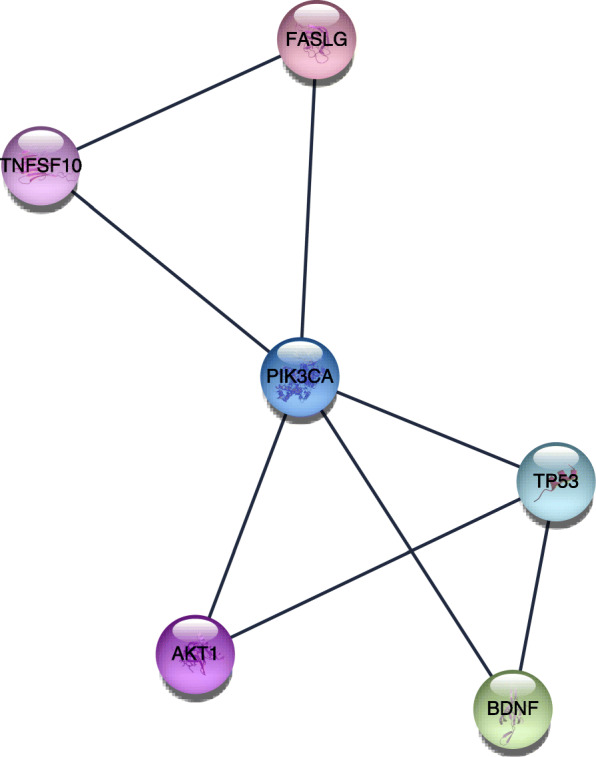

Fig. 7.

The third significant module 3 from the PPI network

Table 5.

Functional and pathway enrichment of module 3 genes

| Category | Term | Count | P value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:1901214~regulation of neuron death | 5 | 2.74E−07 | AKT1, BDNF, TP53, PIK3CA, FASLG |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0043066~negative regulation of apoptotic process | 6 | 2.83E−07 | AKT1, TNFSF10, BDNF, TP53, PIK3CA, FASLG |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0043069~negative regulation of programmed cell death | 6 | 3.02E−07 | AKT1, TNFSF10, BDNF, TP53, PIK3CA, FASLG |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0061695~transferase complex, transferring phosphorus-containing groups | 2 | 0.084109658 | TP53, PIK3CA |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005126~cytokine receptor binding | 3 | 0.002992627 | TNFSF10, BDNF, FASLG |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005102~receptor binding | 4 | 0.007267044 | TNFSF10, BDNF, TP53, FASLG |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0051721~protein phosphatase 2A binding | 2 | 0.0086928 | AKT1, TP53 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04010:MAPK signaling pathway | 4 | 4.65E−04 | AKT1, BDNF, TP53, FASLG |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04151:PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 4 | 0.001159592 | AKT1, TP53, PIK3CA, FASLG |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04150:mTOR signaling pathway | 2 | 0.041464218 | AKT1, PIK3CA |

The interactions between drugs and genes

Using three important modules, 22 genes were selected as possible drug targets, and 32 autophagy-related drugs were identified as potential agents used for LDD therapy (Table 6). Possible gene targets were as follows: TP53 (two drugs), IL-6 (one drug), MMP1 (three drugs), STAT3 (one drug), MMP9 (two drugs), TNF (eleven drugs), IL1B (three drugs), PIK3CA (five drugs), IL-1A (one drug), MMP (two drugs), AKT1 (three drugs), and MMP13 (three drugs). These drugs were generally approved for treating osteoarthritis, psoriasis, vascular wrist joint disease, malignancy, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and inflammatory diseases.

Table 6.

Candidate drugs targeting genes

| Number | Drug | Gene | Interaction type | Score | Approved? | Reference (PubMed ID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acitretin | STAT3 | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 2 | Adalimumab | TNF | Inhibitor | 12 | Yes | 12044041 |

| 3 | Arsenic trioxide | AKT1 | Inducer | 6 | Yes | 12472888 |

| 4 | Aspirin | TP53 | Acetylation | 2 | Yes | 21475861 |

| 5 | Bortezomib | TP53 | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 6 | Canakinumab | IL1B | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | 19169963 |

| 7 | Candicidin | PIK3CA | Inhibitor | 3 | Yes | 26839307 |

| 8 | Captopril | MMP2, MMP9 | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | 12381651 |

| 9 | Certolizumab pegol | TNF | Inhibitor | 6 | Yes | 22917017 |

| 10 | Doxycycline calcium | MMP1, MMP13 | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 11 | Doxycycline hyclate | MMP1, MMP13 | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 12 | Doxycycline hydrate | MMP1, MMP13 | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 13 | Etanercept | TNF | Inhibitor | 12 | Yes | 10375846 |

| 14 | Everolimus | AKT1 | Inhibitor | 3 | Yes | None found |

| 15 | Gallium nitrate | IL1B | Inhibitor | 3 | Yes | 16122880 |

| 16 | Glucosamine | MMP9 | Antagonist | 6 | Yes | 12405690 |

| 17 | Golimumab | TNF | Inhibitor | 6 | Yes | 21079302 |

| 18 | Idelalisib | PIK3CA | Inhibitor | 5 | Yes | 26466009 |

| 19 | Inamrinone | TNF | Inhibitor | 6 | Yes | 11805217 |

| 20 | Infliximab | TNF | Inhibitor | 17 | Yes | 16456024 |

| 21 | Lenalidomide | TNF | Inhibitor | 2 | Yes | None found |

| 22 | Nelfinavir | AKT1 | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 23 | Oxazepam | PIK3CA | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 24 | Pentoxifylline | TNF | Antibody | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 25 | Phenmetrazine | PIK3CA | Inhibitor | 33 | Yes | 27672108 |

| 26 | Pirfenidone | TNF | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 27 | Pomalidomide | TNF | Inhibitor | 2 | Yes | 22917017 |

| 28 | Rilonacept | IL1A, IL1B | Binder | 5 | Yes | 23319019 |

| 29 | Siltuximab | IL6 | Inhibitor | 4 | Yes | 8823310 |

| 30 | Thalidomide | TNF | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | 8755512 |

| 31 | Tiludronic acid | MMP2 | Inhibitor | 1 | Yes | None found |

| 32 | Yohimbine | PIK3CA | Inhibitor | 35 | Yes | 27672108 |

Discussion

The selected 22 genes and their targeted drugs and the related pathways were classified.

Genes, targeted agents, and related pathways involved in LDD pathology

Genes, targeted agents, and gene-related pathways in association with disc catabolism

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are involved in the extracellular matrix proteins (ECM) degradation. Upregulated MMPs or decrease of their inhibitors (TIMPs) could result in an imbalance in ECM.

MMP-1: The expression of MMP-1 in LDD was elevated [17]. Doxycycline hydrate, doxycycline calcium, and doxycycline hyclate specifically inhibited MMP13 and MMP1.

MMP-2: MMP-2 might play an important role in the pathogenesis of LDD and could be a possible target in treatment [18]. Captopril and tiludronic acid are specific agents inhibiting MMP-2.

MMP-9: MMP-9 and IL-1α levels were increased in the degenerated lumbar disc as the disease progressed [19]. Glucosamine and captopril are specific agents inhibiting MMP-9.

MMP-13 and MMP-3: Estradiol could protect nucleus pulposus cells (NPC) from apoptosis caused by deprivation of the serum and regulate MMP-13 and MMP-3 levels via promoting autophagy [20]. In addition, it was found that BRD4 inhibited the expression of MMP-13 in diabetics-related degeneration of intervertebral disc via modulating autophagy, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways [21].

TIMP1: MMPs could be inhibited by the proteins encoded by the genes in the TIMP family. Kwon et al. presented that MMP-1, MMP-3, and IL-8 levels were remarkably elevated in lumbar disc cells under hypoxia condition, while TIMP-2 and TIMP-1 levels were downregulated [22].

Genes, targeted agents, and related pathways in disc anabolism

IGF1: Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and its receptor (IGF1R) can modulate the synthesis of ECM and play an important part in the normal function of the disc. It was reported that downregulated IGF1R could promote LDD in rats [23]. The PI3k/Akt signaling pathway was activated by IGF-1 to prevent LDD [24].

ACAN: The protein encoded by ACAN is an essential ingredient in the extracellular matrix of cartilage tissues. Metformin could increase the expression levels of anabolic genes like Col2a1 and Acan and suppress catabolic genes like Adamts5 and Mmp3 in NPC [25].

SPARC: As a kind of glycoprotein, SPARC plays a pivotal part in regulating the interaction between matrix and cells. Gruber et al. suggested that the expression of the SPARC gene in LDD decreased [26].

In summary, the above studies have shown that the long-term imbalance between catabolism and anabolism in the intervertebral disc changes its composition, contributing to LDD. Nonetheless, autophagy can modulate this imbalance, thereby inhibiting LDD.

Genes, targeted agents, and pathways in relationship with inflammatory factors in LDD

IL1β: It is considered as an essential mediator in inflammatory responses. Zhang et al. presented that melatonin regulated the remodeling of extracellular matrix induced by IL-1β in human NPC and ameliorated inflammation and degeneration of intervertebral disc in rats [27]. Gallium nitrate and canakinumab are specific agents inhibiting L1β.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α): TNF-α encodes the pro-inflammatory cytokine belonging to the TNF family. It was found that TNF was a critical factor in LDD [28]. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that TNF-α could increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in cells and cause osteogenic differentiation and cellular senescence in cartilage endplate stem cells (CESCs); however, autophagy could protect CESCs from oxidative injuries elicited by TNF-α and senescence [29]. Thalidomide, pirfenidone, certolizumab pegol, lenalidomide, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, inamrinone, and pomalidomide are specific agents inhibiting TNF. Additionally, pentoxifylline acts as a specific antibody for TNF.

IL-6: IL-6 plays a pivotal part in inflammatory responses and the maturation of B cells. It was found that microRNA-21 levels were elevated in lumbar intervertebral discs of patients with nerve root pain, which could enhance IL-6 mediated inflammation and attenuate autophagy [30]. Siltuximab is a specific agent inhibiting IL-6.

IL-1a: IL-1a cytokine could be secreted by macrophages and monocytes. Cellular injuries could promote the hydrolysis of the premature IL-1a cytokine and its mature form could induce apoptosis. Chen et al. presented that IL-1α participated in LDD pathogenesis via enhancing the enzymes related to the degradation of extracellular matrix and suppressing the production of extracellular matrix [31]. Rilonacept is a specific binder to IL-1β and IL-1A.

IL-10 and IL-4:shDNMT1 could reduce expressions of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-1β; increase expressions of IL-10 and IL-4; and ameliorate apoptosis in the degenerated discs and LDD-related pain [32]. Furthermore, Hanaei et al. showed that genetic alterations in anti-inflammatory genes could destroy intervertebral disc homeostasis and cause degeneration [33].

STAT3: STAT3 protein regulates the expression levels of multiple genes and thus has an essential part in various cellular activities including cell apoptosis and growth. Acitretin is a specific agent inhibiting STAT3.

To conclude, the inflammation-related factors accelerated disc degeneration via increasing the production of the enzymes related to extracellular matrix degradation, but autophagy could ameliorate inflammatory responses to protect the intervertebral disc.

There are 4 significant autophagy-related pathways in LDD

Three autophagy-associated pathways participate in ameliorating neuro-inflammation and apoptosis via enhancing autophagy in lumbar disc degeneration

AMPK signaling pathway

It was reported that activating autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR pathway was a kind of cellular adaptation when the cells were injured by hyperosmotic stress [34]. Besides, resveratrol reduced MMP-3 levels induced by TNF-α in NPC via the activation of autophagy through the AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway [35]. Zhang et al. proved that naringin could promote the autophagy via the AMPK signaling pathway to attenuate apoptosis induced by oxidative stress in NPC [36].

mTOR signaling pathway

Jiang et al. showed that glucosamine could stimulate autophagy through the mTOR pathway and protect NPC after hydrogen peroxide (100 μM H2O2) or IL-1β treatment [37]. Autophagy and the mTOR signaling pathway were activated when cells in the intervertebral disc were of low nutrient, including low glucose, oxygen, or pH [38].

PI3K-Akt signaling pathway

Autophagy of NPC could be induced by compression stress via suppressing the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and stimulating the JNK pathway [39]. Guo et al. demonstrated that resveratrol could promote the synthesis of the matrix in NPC via increasing autophagy through the PI3K/Akt pathway in oxidative stress (100 μM H2O2) [40]. Moracin M could repress inflammation in NPC through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [41].

To conclude, deprivation of nutrients, hyperosmotic condition, compression damage, inflammation factors, and oxidative injuries could enhance autophagy via various pathways. Afterwards, the activated autophagy could reduce apoptosis, decrease catabolism through downregulating MMPs, enhance the synthesis of the matrix in NPC, and ameliorate inflammation in NPC. TNFSF10, AKT1, and PIK3CA participated in these pathways.

AKT1: In neurological system development, AKT plays an essential part in mediating neuron survival induced by growth factors. Arsenic trioxide is a specific agent stimulating AKT1, while nelfinavir and everolimus have the opposite effects.

PIK3CA: PIK3CA protein represents catalytic subunit. Yohimbine, oxazepam, candicidin, phenmetrazine, and idelalisib are specific agents inhibiting PIK3CA.

TNFSF10: TNFSF10 protein belongs to the family of TNF ligands. Caspase 3, MAPK8/JNK, and caspase 8 were proved to be activated after TNFSF10 bound with its receptor.

There is an autophagy-associated pathway in LDD

ERK signaling pathway

BDNF, TP53, and FASLG play an important role in this pathway.

FASLG: FASLG belongs to the TNF family. FASLG protein could stimulate apoptosis after binding with FAS.

TP53: TP53 protein works as a tumor suppressor containing domains of oligomerization, transcriptional activation, and DNA binding. Bortezomib is a specific agent inhibiting TP53.

BDNF: BDNF protein belongs to the nerve growth factor family. The survival of neurons could be enhanced after BDNF protein is bound with its receptors in the brain of adults.

ERK signaling pathway was in a close relationship with LDD. Autophagy reduced NPC apoptosis induced by compression through the MEK/ERK/NRF1/Atg7 pathways [42]. Nonetheless, Chen et al. proved that H2O2 could stimulate autophagy in an early phase through the ERK/mTOR pathway, and the apoptosis rate of the cells injured by H2O2 (400 μM) could be decreased by inhibiting autophagy [43].

In summary, oxidative injuries (H2O2) could stimulate autophagy via various pathways. According to Chen et al.’s study, apoptosis could be promoted when autophagy was induced by 400-μM H2O2. In the research by Jiang and Gao, apoptosis could be inhibited when autophagy was induced by 100-μM H2O2. Based on previous research, it could be concluded that oxidative stress of various levels could result in autophagy which played a variety of roles.

As such, it could be speculated on the associations among apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy. Autophagy has a bidirectional activity both in inhibiting and inducing apoptosis. However, from our point of view, apoptosis induced by autophagy might have benefits. For the cells which are severely injured, autophagy can promote programmed apoptosis so that greater damages induced by necrosis can be avoided, and thus, more energy can be reserved to repair the cells which have milder injuries. Generally, autophagy can be considered as a beneficial biological process.

There is also a limitation in our research. The function of the selected genes was not proved through experiments but obtained from databases. Therefore, it remains to be further verified by molecular biology experiments.

Conclusion

To conclude, a method was proposed to discover possible key genes, signaling pathways, and potential drugs in relationship with autophagy and LDD. There were 22 possible genes, 4 pathways, and 32 potential drugs, providing a theoretical basis and new insight for basic research and treatment of LDD. Nonetheless, experiments are required in future research to verify the function of the selected genes, pathways, and drugs.

Acknowledgements

We are appreciative to Han Changxu for the help in the study.

Abbreviations

- BP

Biological processes

- LDD

Lumbar disc degeneration

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GO

Gene Ontology

- CC

Cellular components

- MCODE

Molecular complex detection

- STRING

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- CESCs

Cartilage endplate stem cells

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- TIMPs

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- NPC

Nucleus pulposus cells

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- DGIdb

Drug Gene Interaction Database

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1β

- MF

Molecular function

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This article has not received any specific funding from public, commercial, or non-profit sector funding agencies.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Waived.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vergroesen PP, Kingma I, Emanuel KS, Hoogendoorn RJ, Welting TJ, van Royen BJ, van Dieën JH, Smit TH. Mechanics and biology in intervertebral disc degeneration: a vicious circle. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(7):1057–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saleem S, Aslam HM, Rehmani MA, Raees A, Alvi AA, Ashraf J. Lumbar disc degenerative disease: disc degeneration symptoms and magnetic resonance image findings. Asian Spine J. 2013;7(4):322–334. doi: 10.4184/asj.2013.7.4.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan AN, Jacobsen HE, Khan J, Filippi CG, Levine M. Inflammatory biomarkers of low back pain and disc degeneration: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1410(1):68–84. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung KM, Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Mok FP, Ho DW, Fong DY, Luk KD. Intervertebral disc degeneration: new insights based on “skipped” level disc pathology. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(8):2392–2400. doi: 10.1002/art.27523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowdell J, Erwin M, Choma T, Vaccaro A, Iatridis J, Cho SK. Intervertebral disk degeneration and repair. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(3S):S46–S54. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemanta D, Jiang XX, Feng ZZ, Chen ZX, Cao YW. Etiology for degenerative disc disease. Chin Med Sci J. 2016;31(3):185–191. doi: 10.1016/S1001-9294(16)30049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221(1):3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaltirik CK, Timirci-Kahraman Ö, Gulec-Yilmaz S, Ozdogan S, Atalay B, Isbir T. The evaluation of proteoglycan levels and the possible role of ACAN gene (c.6423T>C) variant in patients with lumbar disc degeneration disease. In Vivo. 2019;33(2):413–417. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song YQ, Karasugi T, Cheung KM, Chiba K, Ho DW, Miyake A. Lumbar disc degeneration is linked to a carbohydrate sulfotransferase 3 variant. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4909–4917. doi: 10.1172/JCI69277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang JH, Zhao LF, Wang HF, Wen YT, Jiang KK, Mao XM, Zhou ZY, Yao KT, Geng QS, Guo D, Huang ZX. GenCLiP 3: mining human genes’ functions and regulatory networks from PubMed based on co-occurrences and natural language processing. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(6):1973-75. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz807. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Thomas PD. The Gene Ontology and the meaning of biological function. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1446:15–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3743-1_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman BT, Huang da W, Tan Q, Guo Y, Bour S, Liu D, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID Knowledgebase: a gene-centered database integrating heterogeneous gene annotation resources to facilitate high-throughput gene functional analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:426. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Gorodkin J, Jensen LJ. Cytoscape StringApp: network analysis and visualization of proteomics data. J Proteome Res. 2019;18(2):623–632. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner AH, Coffman AC, Ainscough BJ. DGIdb 2.0: mining clinically relevant drug-gene interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1036–D1044. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng B, Ren JZ, Meng XQ, Pang CG, Duan GQ, Zhang JX, Zou H, Yang HZ, Ji JJ. Expression profiles of MMP-1 and TIMP-1 in lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(4):19080–19086. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.29.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rastogi A, Kim H, Twomey JD, Hsieh AH. MMP-2 mediates local degradation and remodeling of collagen by annulus fibrosus cells of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(2):R57. doi: 10.1186/ar4224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li PB, Tang WJ, Wang K, Zou K, Che B. Expressions of IL-1α and MMP-9 in degenerated lumbar disc tissues and their clinical significance. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(18):4007–4013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ao P, Huang W, Li J, Wu T, Xu L, Deng Z, Chen W, Yin C, Cheng X. 17β-Estradiol protects nucleus pulposus cells from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis and regulates expression of MMP-3 and MMP-13 through promotion of autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503(2):791–797. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Hu J, Chen X. BRD4 inhibition regulates MAPK, NF-κB signals, and autophagy to suppress MMP-13 expression in diabetic intervertebral disc degeneration. FASEB J. 2019;33(10):11555–11566. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900703R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon WK, Moon HJ, Kwon TH, Park YK, Kim JH. The role of hypoxia in angiogenesis and extracellular matrix regulation of intervertebral disc cells during inflammatory reactions. Neurosurgery. 2017;81(5):867–875. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Zheng XF, Ni BB, Yang YH, Jiang SD, Lu H, Jiang LS. Reduced expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor leads to accelerated intervertebral disc degeneration in mice. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2013;26(2):337–347. doi: 10.1177/039463201302600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Zhou K, Fu W, Zhang H. Insulin-like growth factor 1 activates PI3k/Akt signaling to antagonize lumbar disc degeneration. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37(1):225–232. doi: 10.1159/000430347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D, Xia D, Pan Z. Metformin protects against apoptosis and senescence in nucleus pulposus cells and ameliorates disc degeneration in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(10):e2441. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruber HE, Ingram JA, Leslie K, Hanley EN., Jr Cellular, but not matrix, immunolocalization of SPARC in the human intervertebral disc: decreasing localization with aging and disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(20):2223–2228. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142225.07927.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, He F, Chen Z, Su Q, Yan M, Zhang Q, Tan J, Qian L, Han Y. Melatonin modulates IL-1β-induced extracellular matrix remodeling in human nucleus pulposus cells and attenuates rat intervertebral disc degeneration and inflammation. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(22):10499–10512. doi: 10.18632/aging.102472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang C, Yu X, Yan Y, Yang W, Zhang S, Xiang Y, Zhang J, Wang W. Tumor necrosis factor-α: a key contributor to intervertebral disc degeneration. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2017;49(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmw112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuo R, Wang Y, Li J, Wu J, Wang W, Li B, Sun C, Wang Z, Shi C, Zhou Y, Liu M, Zhang C. Rapamycin induced autophagy inhibits inflammation-mediated endplate degeneration by enhancing Nrf2/Keap1 signaling of cartilage endplate stem cells. Stem Cells. 2019;37(6):828–840. doi: 10.1002/stem.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin H, Zhang W, Zhou T, Li W, Chen Z, Ji C, Zhang C, He F. Mechanism of microRNA-21 regulating IL-6 inflammatory response and cell autophagy in intervertebral disc degeneration. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(2):1441–1444. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Ma H, Bi D, Qiu B. Association of interleukin 1 gene polymorphism with intervertebral disc degeneration risk in the Chinese Han population. Biosci Rep. 2018;38(4):BSR20171627. doi: 10.1042/BSR20171627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou Y, Shi G, Guo Y, Shi J. Epigenetic modulation of macrophage polarization prevents lumbar disc degeneration. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(8):6558–6569. doi: 10.18632/aging.102909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanaei S, Abdollahzade S, Sadr M, Mirbolouk MH, Khoshnevisan A, Rezaei N. Association of IL10 and TGFB single nucleotide polymorphisms with intervertebral disc degeneration in Iranian population: a case control study. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12881-018-0572-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang LB, Cao L, Yin XF, Yasen M, Yishake M, Dong J, Li XL. Activation of autophagy via Ca(2+)-dependent AMPK/mTOR pathway in rat notochordal cells is a cellular adaptation under hyperosmotic stress. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(6):867–879. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1004946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang XH, Zhu L, Hong X, Wang YT, Wang F, Bao JP, Xie XH, Liu L, Wu XT. Resveratrol attenuated TNF-α-induced MMP-3 expression in human nucleus pulposus cells by activating autophagy via AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2016;241(8):848–853. doi: 10.1177/1535370216637940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z, Wang C, Lin J, Jin H, Wang K, Yan Y, et al. Therapeutic potential of naringin for intervertebral disc degeneration: involvement of autophagy against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in nucleus pulposus cells. Am J Chin Med. 2018;46(7):1561-80. 10.1142/S0192415X18500805. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Jiang L, Jin Y, Wang H, Jiang Y, Dong J. Glucosamine protects nucleus pulposus cells and induces autophagy via the mTOR-dependent pathway. J Orthop Res. 2014;32(11):1532–1542. doi: 10.1002/jor.22699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yurube T, Ito M, Kakiuchi Y, Kuroda R, Kakutani K. Autophagy and mTOR signaling during intervertebral disc aging and degeneration. JOR Spine. 2020;3(1):e1082. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, Wang J, Deng X, Huang D, Shao Z, Ma K. Compression stress induces nucleus pulposus cell autophagy by inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and activation of the JNK pathway. Connect Tissue Res. 2020;61(1):1–13. 10.1080/03008207.2020.1736578. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Gao J, Zhang Q, Song L. Resveratrol enhances matrix biosynthesis of nucleus pulposus cells through activating autophagy via the PI3K/Akt pathway under oxidative damage. Biosci Rep. 2018;38(4):BSR20180544. doi: 10.1042/BSR20180544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Guo F, Zou Y, Zheng Y. Moracin M inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in nucleus pulposus cells via regulating PI3K/Akt/mTOR phosphorylation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;58:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Hua W, Wang K. Autophagy attenuates compression-induced apoptosis of human nucleus pulposus cells via MEK/ERK/NRF1/Atg7 signaling pathways during intervertebral disc degeneration. Exp Cell Res. 2018;370(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen JW, Ni BB, Li B, Yang YH, Jiang SD, Jiang LS. The responses of autophagy and apoptosis to oxidative stress in nucleus pulposus cells: implications for disc degeneration. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34(4):1175–1189. doi: 10.1159/000366330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.