Dysregulated metabolism contributes to central characteristics of cancer cells such as sustained proliferation, resistance toward cell death, and epigenetic alterations (1). At the same time, the process of cellular transformation and tumorigenesis creates new metabolic challenges. Cancer cells commonly encounter harsh metabolic conditions such as poorly vascularized tumors or distant tissues, where they are exposed to fluctuating or unfamiliar nutrient environments. Cancer cells navigate these metabolic stresses by selecting for increased metabolic flexibility and resilience. To better understand the underlying processes, Tsai et al. (2) explore in PNAS the adaptations of pancreatic cancer cells to limited nutrient supply, as is characteristic for solid tumors.

Research into cancer metabolism initially focused on processes that increase anabolism and growth. Many cancer cells avidly take up glucose and excrete excess glucose-derived carbons as lactate—a phenomenon referred to as aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect (3). Cancer cells further take up large quantities of glutamine, a nonessential amino acid that provides a source for both reduced carbon and nitrogen. In proliferating cells, glucose and glutamine constitute major fuels for central carbon metabolism, which supplies energy, reducing equivalents and biosynthetic precursors (1, 3).

Although glucose and glutamine are preferred nutrients, cancer cells often compensate for shortage of either glucose or glutamine by increasing utilization of the other nutrient. Metabolism of glucose and glutamine supplies reduced carbons to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, which generates electrons for the respiratory chain as well as various biosynthetic precursors. Flexible use of either glucose or glutamine for TCA cycle anaplerosis thus allows cancer cells to sustain these metabolic activities (1, 4). Glutamine further serves as a source of reduced nitrogen, which is required for the biosynthesis of amino acids, nucleotides, and amino sugars. However, when glutamine is limiting, expression of branched chain amino acid transferases enables cancer cells to acquire reduced nitrogen from isoleucine, leucine, and valine (5).

The remarkable metabolic flexibility of cancer cells has received increasing attention, but the underlying mechanisms are insufficiently understood. Addressing this problem is imperative, not only for the fundamental understanding of cancer metabolism but also, for its therapeutic exploitation. A case in point is the development of pharmacological inhibitors of glycolysis and glutaminolysis, which have not lived up to expectations. In light of the centrality of glucose and glutamine metabolism, this may have been unexpected, yet we retrospectively appreciate the metabolic flexibility through which cancer cells evade inhibition of either pathway. Tsai et al. (2) investigated mechanisms that promote such metabolic plasticity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA). PDA is a highly desmoplastic, poorly vascularized tumor whose nutrient levels differ from those found in plasma (6, 7). As a consequence of the metabolically harsh tumor microenvironment, PDA cells display various metabolic adaptations including alterations in glucose and glutamine metabolism (8). The idiosyncratic nature of PDA metabolism suggests it as a promising therapeutic target, but efforts have been frustrated so far.

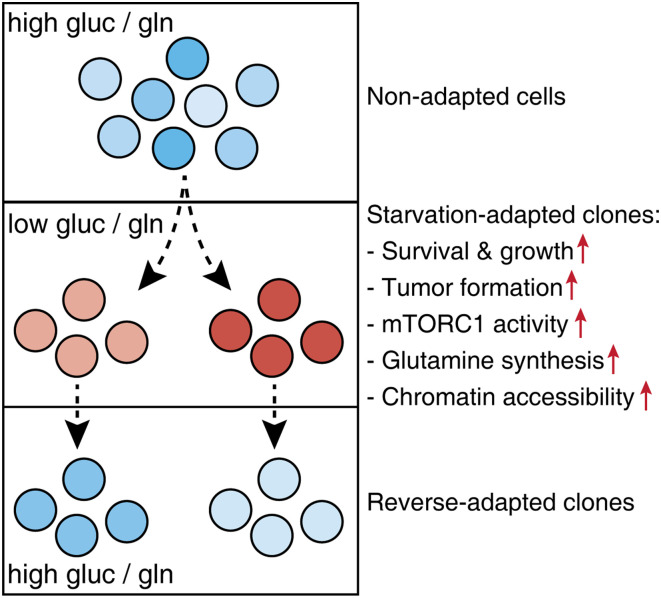

To establish a tractable experimental system for investigating metabolic plasticity, Tsai et al. (2) selected PDA cell lines in media with decreased levels of glucose and glutamine (Fig. 1). While most PDA cells within a few days succumbed to starvation, some cells managed to survive and eventually resume proliferation. These starvation-adapted PDA clones were capable of growing under glucose/glutamine limitation while retaining normal proliferation rates in nutrient-replete conditions. Starvation-adapted clones further displayed improved tumor formation in mice, suggesting that adapting to nutrient starvation increased their oncogenic potential.

Fig. 1.

Investigating metabolic plasticity in pancreatic cancer cells. Several human PDA cell lines were cultured in starvation media (0.5 mM glucose [gluc]/0.1 mM glutamine [gln]) for several weeks. From the surviving cells, several clonal lines were established. Starvation-adapted clones could proliferate in glucose/glutamine-deprived media and displayed increased tumor formation in mice. Adapted clones further displayed consistent molecular alterations, including increased mTORC1 activity, glutamine synthesis, and chromatin accessibility. These changes were reversible and gradually lost when starvation-adapted clones were reverted to full media.

To characterize alterations that support growth under glucose/glutamine-restricted conditions, the authors examined the metabolomes of adapted vs. nonadapted PDA clones (2). Glucose/glutamine deprivation caused widespread metabolome changes in nonadapted cells. Strikingly, many of these alterations were reversed in starvation-adapted clones, whose metabolome more closely resembled the metabolite profile of well-nourished cells. Increased growth potential and metabolic alterations of starvation-adapted clones were primarily attributed to glutamine deprivation. Albeit a major substrate for metabolic pathways, glutamine is a nonessential amino acid that can in principle be synthesized endogenously. Indeed, the authors observed that adapted PDA clones increased de novo glutamine synthesis and utilized branched chain amino acids as a source of reduced nitrogen for glutamine production.

Cells constantly monitor nutrient availability and adjust their metabolic activities accordingly. The kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) is the central cellular amino acid sensor (9). mTORC1 becomes activated by intracellular abundance of several amino acids including glutamine and in turn, promotes protein translation as well as other anabolic processes. Over longer periods of time, nutrient availability can instruct persistent transcriptional changes by altering the activity of chromatin-modifying enzymes. In fact, the substrates and cofactors of the enzymes that deposit or remove acetyl and methyl groups on chromatin are all derived from central carbon metabolism. Thus, availability of glucose and glutamine can alter epigenetic marks by modulating enzyme activities (10, 11).

To understand how starvation-adapted clones acquire glutamine, the authors investigated regulation of glutamine synthetase, the enzyme that generates glutamine from glutamate and reduced nitrogen (2). mTORC1 activity was found to stabilize glutamine synthetase by preventing its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. While PDA cells normally respond to glucose/glutamine deprivation with inactivation of mTORC1, adapted PDA clones could sustain mTORC1 activity under starvation. This led to stabilization of glutamine synthetase and a resulting increase in de novo glutamine synthesis, which sustained proliferation in the context of glutamine deprivation. Glutamine synthetase levels are also regulated by glutamine availability directly: an abundance of glutamine induces proteasomal degradation of the enzyme, thereby preventing costly endogenous synthesis when glutamine is available from extracellular sources (12). Conceivably, sustained mTORC1 activity and glutamine deprivation conspire to elevate glutamine synthetase levels in starvation-adapted PDA cells.

Tsai et al. now provide compelling evidence that by stabilizing glutamine synthetase, sustained mTORC1 activity can be beneficial under glutamine deprivation.

Which molecular processes underlie the adaptation of PDA cells to growth under nutrient deprivation? Constitutive mTORC1 activity may be part of the answer, but this does not explain how mTORC1 eludes starvation-induced inactivation in the first place. Rather, more persistent alterations such as genetic or transcriptional changes could contribute to the adaptation phenotype. An earlier study investigating adaptation of colorectal cancer cells to glucose-deprived media documented the emergence of oncogenic mutations in the small GTPase KRAS, which had not been present in parental cells (13). However, whole-exome sequencing of starvation-adapted PDA clones did not identify analogous mutations. Rather, adapted PDA clones displayed widespread changes in chromatin accessibility and messenger RNA abundance. This suggests that epigenetic changes contributed to the starvation adaptation of PDA cells. Importantly, epigenetic alterations are in principle reversible. Indeed, when cultured in nutrient-replete media, adapted clones displayed a gradual reversal of their epigenetic and transcriptional state.

While mTORC1 inhibitors efficiently suppress cancer cell proliferation in nutrient-replete conditions, the impact of mTORC1 on cancer cell fitness under starvation remains controversial. Several studies suggested that cellular survival during glucose or amino acid starvation required mTORC1 inactivation (14, 15). Tsai et al. (2) now provide compelling evidence that by stabilizing glutamine synthetase, sustained mTORC1 activity can be beneficial under glutamine deprivation. These discrepancies might arise from differences in cellular context, but a perhaps more interesting explanation is the differences in experimental approach: While mTORC1 is usually activated or suppressed by genetic or pharmacological means, the authors let cancer cells select for optimal mTORC1 activity under persistent nutrient limitation. Conceivably, this allowed accumulation of epigenetic changes that reconcile high mTORC1 activity with nutrient shortage.

The remarkable metabolic plasticity of cancer cells raises the question of how to best exploit dysregulated metabolic pathways as therapeutic targets. Oncogenic mutations enforce specific metabolic phenotypes—for instance, the activating KRAS mutations that are quasiuniversal in PDA increase glucose transporter expression (1, 8). Such mutations create metabolic vulnerabilities that could inform therapeutic strategies. However, Tsai et al. (2) identify metabolic adaptations that are plastic, which could thwart therapeutic interventions, and are not caused by mutations, which hinders patient stratification. The authors argue that metabolic plasticity in turn creates new dependencies that could be exploited, for instance by using glutamine synthetase inhibitor to target cancer cells in hypovascularized tumor regions. Their comprehensive characterization of PDA cell adaptations to nutrient starvation provides a framework in which to explore such codependencies.

Footnotes

The author declares no competing interest.

See companion article, “Adaptation of pancreatic cancer cells to nutrient deprivation is reversible and requires glutamine synthetase stabilization by mTORC1,” 10.1073/pnas.2003014118.

References

- 1.Pavlova N. N., Thompson C. B., The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 23, 27–47 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai P.-Y.et al., Adaptation of pancreatic cancer cells to nutrient deprivation is reversible and requires glutamine synthetase stabilization by mTORC1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2003014118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vander Heiden M. G., Cantley L. C., Thompson C. B., Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029–1033 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palm W., Thompson C. B., Nutrient acquisition strategies of mammalian cells. Nature 546, 234–242 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayers J. R., et al., Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science 353, 1161–1165 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamphorst J. J., et al., Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res. 75, 544–553 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan M. R., et al., Quantification of microenvironmental metabolites in murine cancers reveals determinants of tumor nutrient availability. Elife 8, e44235 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biancur D. E., Kimmelman A. C., The plasticity of pancreatic cancer metabolism in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1870, 67–75 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxton R. A., Sabatini D. M., mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 168, 960–976 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wellen K. E., et al., ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 324, 1076–1080 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey B. W., Finley L. W., Cross J. R., Allis C. D., Thompson C. B., Intracellular α-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature 518, 413–416 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen T. V., et al., Glutamine triggers acetylation-dependent degradation of glutamine synthetase via the thalidomide receptor cereblon. Mol. Cell 61, 809–820 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yun J., et al., Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of KRAS pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science 325, 1555–1559 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choo A. Y., et al., Glucose addiction of TSC null cells is caused by failed mTORC1-dependent balancing of metabolic demand with supply. Mol. Cell 38, 487–499 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demetriades C., Doumpas N., Teleman A. A., Regulation of TORC1 in response to amino acid starvation via lysosomal recruitment of TSC2. Cell 156, 786–799 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]