Abstract

Background: All applicants to accredited training programs must write a personal statement as part of the application process. This may provoke anxiety on the part of the applicant and can result in an impersonal product that does not enhance his or her application. Little has been written about what program directors are seeking in personal statements.

Objective: To gain a better understanding of how pulmonary and critical care fellowship program directors view and interpret these essays and to help applicants create more effective personal statements and make the writing process less stressful.

Methods: We surveyed the membership of the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors in 2018. Quantitative data were collected regarding the importance of the personal statement in the candidate selection process. Qualitative data exploring the characteristics of personal statements, what the personal statement reveals about applicants, and advice for writing them were also collected. Comparative analysis was used for coding and analysis of qualitative data.

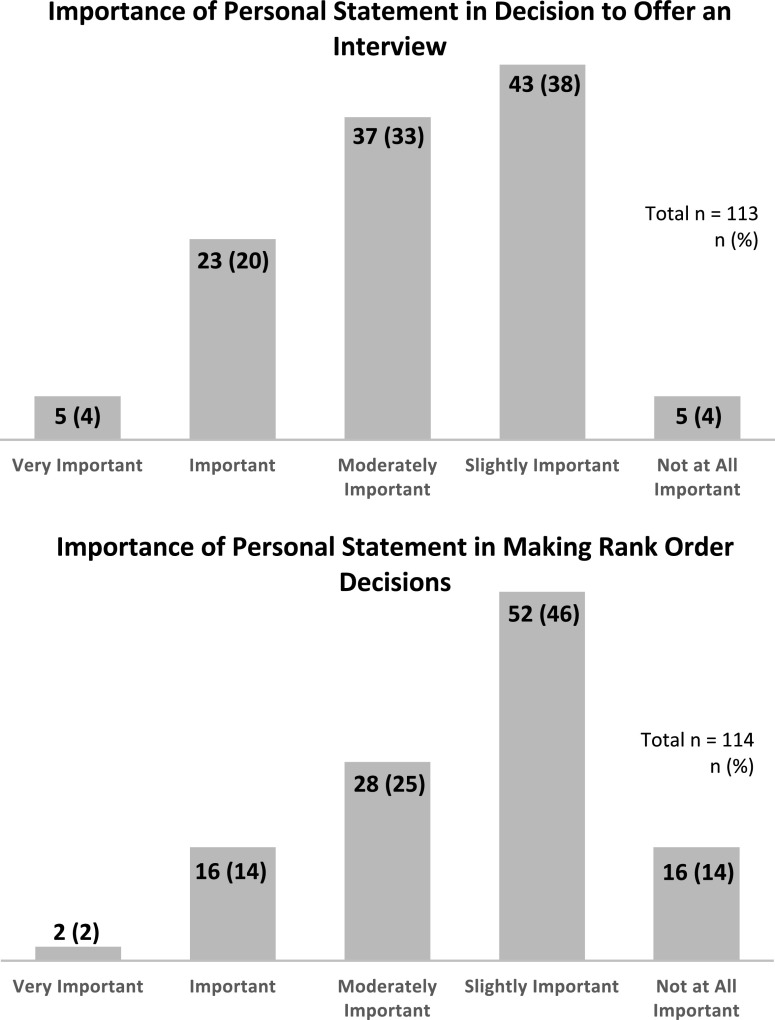

Results: Surveys were completed by 114 out of 344 possible respondents (33%). More than half of the respondents believed that the personal statement is at least moderately important when deciding to offer an interview, and 40% believed it is at least moderately important when deciding rank order. A qualitative analysis revealed consistent themes: communication skills, provision of information not found elsewhere, applicant characteristics, and things to avoid.

Conclusion: The respondents view the personal statement as moderately important in the application process. They value succinct, quality writing that reveals personal details not noted elsewhere. The information presented may help reduce anxiety associated with writing the personal statement and result in making the personal statement a more meaningful part of the application.

Keywords: graduate medical education, personal statements, pulmonary and critical care fellowship, program director

Every year, thousands of residency and fellowship applications are submitted through the Electronic Residency Application Service, and there were 752 applications for 568 pulmonary and critical care medicine positions in 2018 (1). These applications include the applicant’s curriculum vitae, letters of recommendation from faculty, licensing exam scores, Medical Student Performance Evaluation, medical school transcript, and personal statement (PS). The PS is the only part of the application that gives the applicant a voice to speak directly to program directors (PDs). Not surprisingly, this can be an anxiety-provoking part of the application process—one study reported that >80% of residency applicants expressed anxiety about writing their PS (2).

PDs believe that many of the PSs they read are impersonal (2, 3), which can lead to a feeling of indifference toward the applicant (4). This type of impersonal statement may cause applicants to lose their only opportunity to reveal themselves on a more personal level and make their application stand out in a positive way.

Despite its importance, little has been written about what PDs of postgraduate training programs seek when evaluating a PS. In light of this, we sought to gain a better understanding of how pulmonary and/or critical care medicine PDs view and interpret PSs in an effort to demystify this process for applicants. The results of this study were presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors (5).

Methods

A survey assessing the importance of the PS was created and is available as Appendix E1 in the online supplement. The survey was initially designed by L.H. and G.B. and was iteratively refined for construct and content validity by four of the authors (L.H., G.B., K.B., and J.M.), all of whom are PDs or associate program directors (APDs). It was internally tested among the authors for ease of use and likelihood of obtaining the desired information. The membership of the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors (APCCMPD) was chosen as a purposive sample, and an online survey was disseminated to its 344 listserv members. This listserv includes both PDs and APDs from institutions across the country. Survey dissemination occurred in March 2018 and an email reminder was sent 1 month later. The survey data were collected using REDCap (hosted at the Indiana University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute) (6), and respondents gave consent by voluntarily completing the survey. The survey included two questions with Likert scale responses assessing the importance of the PS both when making a decision to offer an interview and when making rank-order decisions. This was followed by four open-ended questions assessing what the PDs learned about applicants from the PS, what characteristics define a good or bad PS, and what advice they offer potential applicants about writing a PS. The survey concluded with collection of demographic data. The Institutional Review Board at Indiana University reviewed the study protocol and determined it was exempt from full review.

The data from the four open-ended questions were analyzed via a qualitative conventional content analysis, which involves deriving themes directly from the data rather than applying preconceived theories to the data (7). Three of the authors (L.H., W.G.C., and G.B.) reviewed the verbatim responses to each question and identified emerging themes, which were further analyzed and grouped into logical major themes and subthemes. A codebook was created and the data were entered into NVivo 12 software for Windows (QRS International) for further data management and analysis. L.H. and G.B. analyzed the full data set using the finalized codebook, which is available in its entirety in Appendix E2. A weighted κ analysis was performed to assess for interrater reliability and yielded a score of 0.73, indicating very good to excellent agreement.

Results

A total of 114 out of 344 surveys (33%) were submitted. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the respondents, including 65 PDs (74%) and 24 APDs (27%). The majority of respondents (96%) were from academic institutions. When asked to rate the importance of the PS in making a decision to offer an interview, 58% of the respondents said that it was at least moderately important, and 40% rated it as at least moderately important in decisions regarding rank order (Figure 1). There was significant overlap in themes identified in the first three questions (what does the PS tell you about an applicant, what characteristics define a good PS, and what characteristics define a bad PS?). The major themes that emerged from this analysis were communication skills, provision of information, applicant characteristics, and things to avoid.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Response rate | 114/344 (33) |

| Program location | |

| Midwest | 24 (27) |

| Northeast | 33 (37) |

| South | 19 (21) |

| West | 13 (15) |

| Outside the United States | 0 (0) |

| Primary program affiliation | |

| Academic | 85 (96) |

| Community based | 4 (4) |

| Veterans Affairs or military | 0 (0) |

| Program type | |

| Critical care only | 5 (6) |

| Pulmonary only | 3 (3) |

| Pulmonary and critical care | 81 (91) |

| Total number of fellows in program | |

| ⩽5 | 4 (4) |

| 6–10 | 23 (26) |

| 11–15 | 31 (35) |

| 16–20 | 14 (16) |

| >20 | 17 (19) |

| Role in fellowship program | |

| Program director | 65 (73) |

| Associate program director | 24 (27) |

| Years as program director | |

| ⩽5 | 54 (61) |

| 6–10 | 20 (22) |

| 11–15 | 8 (9) |

| 16–20 | 4 (4) |

| >20 | 3 (3) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 36 (40) |

| Male | 52 (58) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (1) |

| Age | |

| ⩽40 yr | 22 (25) |

| 41–60 yr | 61 (69) |

| >60 yr | 4 (4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (2) |

Figure 1.

Quantitative responses to questions about the importance of the personal statement in decision-making.

Communication Skills

The PS is frequently viewed as a way to assess communication skills and thought processes.

“I get a sense of the fluidity of their thought and their ability to communicate.” [p. 16]

Many PDs indicated that bad writing could be interpreted as a surrogate marker for a poor work ethic or a lack of effort. Poor writing was also viewed as a sign that the applicant may simply not have the skills needed to be successful in the field.

“Misspellings, bad grammar, and poor attention to writing detail [are] a big sign that they maybe don’t have the attention to detail to [be] a fellow in critical care.” [p. 3]

Finally, the ability to express thoughts and ideas succinctly rather than rambling was valued. Many PDs mentioned that the PS should be no longer than one page, notably highlighted thusly:

“Usually no souls are saved after the first page.” [p. 46]

Provision of Information

As previously noted, the PS is the only part of the application that gives the applicant a voice. Respondents value being given information about the applicant that cannot be discovered from reviewing the other portions of the application.

“Person reading this one page should be able to describe you without even meeting you.” [p. 31]

A discussion about an applicant’s career plans is valuable to respondents. This allows the interview day to be arranged so that applicants can meet faculty members who have similar career interests and could be potential mentors.

“A good personal statement gives a sense of career direction.” [p. 52]

“[I look] to see what the applicant’s intended career path…and…clinical areas of interest [are]. I use this information to structure the interview day to best answer their questions and attempt to select interviewers that align with [their] interests and career goals.” [p. 9]

Other personal information, such as unique life experiences and pathways leading to the applicant’s current career trajectory, is also valued.

“It focuses on one of the words in the title...‘personal.’ Good statements tell you things about the applicant that you can’t glean from their [curriculum vitae] or letters of recommendation. What makes this person someone we’d want to talk to further and potentially work with for 1–2 years? What are things that are important to you in and out of medicine? Where do you see yourself going after fellowship? How can we help you achieve your goals?” [p. 15]

Sharing this kind of information helps the PD get to know the applicant as a person and can make the application stand out from the others.

Applicant Characteristics

PDs appreciate getting a glimpse into the personality and character of the applicants.

“It often gives me a unique hook about the person that sticks with me, and I sometimes catch myself thinking of that candidate and even referring to them as ‘the one who wrote about ____ in their personal statement.’” [p. 46]

“What are some things that make you tick and are important to you outside of medicine?” [p. 11]

One characteristic that is highly valued is resilience (8). Multiple respondents highlighted the importance of resilience, and the following may best sum up the importance they place on this trait:

“The best personal statements convey some perception of their resilience, which is not always focused on medicine, but life in general.” [p. 70]

Finally, the characteristics of humility and maturity are highly valued. Like most fields of medicine, pulmonary and critical care medicine requires a great deal of collaboration and teamwork, and applicants who possess these character traits are sought after by respondents.

“Humility and maturity are welcomed and work well at convincing me to invite for an interview, when they come across in the statement, even if the scores are not spectacular.” [p. 16]

This last statement highlights the impact a PS can have in the decision to offer candidates an interview.

Things to Avoid

PDs frequently comment on the need to avoid generic, cookie-cutter statements that look like most of the other statements they read. One of the biggest things to avoid is failing to address a problem spot or “red flag” in the application.

“[Applicants should note things]. . . like a large drop or failure on USMLE—if they fail to list why this happened [it] seems like they are hiding [something].” [p. 89]

In addition, the “hero story” of an applicant’s big save in the critical care unit is seen as cliché and overused.

“I don’t like those that relate some critical care hero story. . . It is terribly common and makes me roll my eyes.” [p. 3]

Similarly, stories of any nature that are sensational but do not reveal anything formative or informative about the applicant should be avoided.

Advice to Applicants

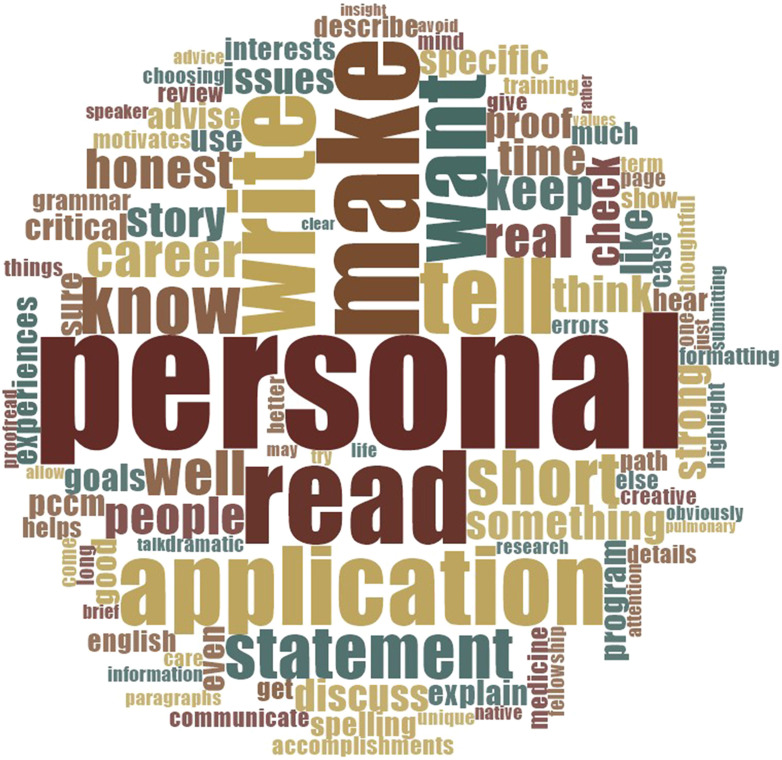

In the last question of our survey, respondents were asked about what advice they give to potential applicants. A word cloud created from these responses highlights the importance of making sure the PS is personal (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Word cloud made from responses to the question, “What advice do you give applicants for writing personal statements?”

“Don’t try to game it. There are no ‘wrong’ statements…only statements that sound contrived and insincere.” [p. 65]

The respondents recommend that applicants should describe experiences in or outside of medicine that show who they are as a person and highlight their personality and/or character traits. Applicants should discuss things that cannot be found elsewhere in the application, or highlight those that may be obscure but are important to their development personally or professionally. The respondents strongly believe that having others read the PS in order to give feedback is an important part of the PS-writing process, in addition to proofreading and checking for errors.

“Make sure it is personal. Have lots of other people who know you well read it and tell you if it reflects who you are.” [p. 46]

Including information about career goals was again frequently mentioned because it allows the reader to get a sense of what the applicant is passionate about, determine whether a particular program has the resources to help the applicant achieve his or her goals, and arrange the interview day to let the applicant meet key people in the division.

“It’s your opportunity to explain what excites you and why, and what you want to be in a decade. Write well, and then show a draft to someone who writes even better.” [p. 12]

Being honest and keeping the PS to no more than one page were highlighted by multiple respondents as key pieces of advice.

Discussion

Although the importance ascribed to the PS varies among specialties, the majority of respondents consider this a factor in making decisions regarding offering an interview, and many also consider it when determining rank order (9). Although the PS may not have a tremendous impact on the decision to offer an interview to an exceptional applicant, for applicants applying to a “reach” program, the data indicate that the PS can have an impact on decisions to offer an interview.

Recognizing the impact that the PS can have on the success of their application can lead to anxiety for trainees (2). Although our study participants were all pulmonary and/or critical care PDs and APDs, we believe the findings presented here are likely generalizable to a wider audience than simply pulmonary and critical care applicants. Several publications have addressed the lack of originality and even plagiarism in PSs (3, 4, 10, 11); however, this is the one of the few studies to provide a large-scale synopsis of what respondents are actually looking for when they review PS submitted as part of a fellowship application.

Although it would seem obvious that a PS submitted as part of a postgraduate training application should be well written, our study suggests that PSs are submitted every year lacking this basic feature. Evidence of this is seen in the large number of respondents who commented on the need to perform basic proofreading of the PS before submission. Trainees should plan to give themselves ample time to write their PS. This is important for both generating content and allowing time to review for spelling, grammar, and structure by other individuals who write well. Applicants for whom writing is not a strength and those for whom English is a second language should take special care to seek another person to review their writing and help them avoid easily correctable errors. Interestingly, although plagiarism in PSs has been identified by the Electronic Residency Application Service as a growing problem (12), this was not identified as a concern by any of our respondents. Finally, communicating in a clear, succinct fashion is vitally important, with many respondents commenting that a PS should not exceed one page.

Our respondents believe that the content of the writing is equally important. The PS is the single portion of the application that allows applicants to speak directly to respondents, and applicants should take advantage of this and make it personal. The advice to make the PS “personal” was highlighted numerous times by our respondents. They were clear that they do not want to read another quote from Sir William Osler or hear another dramatic story about a life saved or diagnosis made that sealed an applicant’s career path decision. These are viewed as overused clichés that fail to make an applicant stand out. Respondents stated that stories shared in the PS should be limited to personal experiences inside and outside of medicine that were truly formative in the applicant’s development as a person or as a professional. These stories should also reveal something of the applicant’s character.

One character trait that is highly valued by our respondents is resilience, defined as “the ability to rebound following adverse experiences” (8). All fields of medicine present challenges. How does the applicant respond to these? Are they seen as opportunities for growth and development or something to be avoided? A prime example here would be the applicant who has a “red flag” in his or her application, such as failing a board exam or repeating a year of medical school or residency. Our respondents want applicants who have encountered these types of challenges to use the PS as a way to explain these circumstances and how they led to personal growth and ultimately success. When done well, directly addressing a vulnerability can ultimately turn a potential negative into an indication of grit and resilience.

The PS is the single portion of the application that allows applicants to speak directly to respondents, and applicants should take advantage of this and make it personal.

Our survey demonstrates that a final key content area is discussion about career goals and expectations for fellowship. The respondents said they value this because it helps them create an interview day that is personalized for the applicant, who can then be matched up with potential mentors and made aware of resources. Having an idea of what an applicant is looking for in a training program provides PDs an opportunity to highlight that on the interview day and give the applicant a better sense of what the program has to offer.

The most obvious limitation to our study is the low response rate of 33%. One probable reason for this is that physician survey response rates have fallen over the last few years (13, 14). In addition, the inclusion of open-ended questions in our survey may have discouraged some from completing it. Another limitation is that our study only represents those who chose to respond to the survey, and may not represent the views of pulmonary and/or critical care medicine PDs as a whole. The majority of our respondents were from academic centers and had <5 years (61%) or <10 years (22%) of experience in their current roles. Our data analysis did not take into account the length of time the PDs had been in their roles, and this type of subgroup analysis would be difficult to perform given the overall number of respondents. However, a recent survey done by the APCCMPD revealed that 39% of PDs reported being in their position for 1–4 years, and another 39% reported 5–10 years of experience (J. Reitzner, M.B.A., M.I.P.H., written communication, November 2019). In light of this, our respondents are likely a representative sample of the APCCMPD membership as a whole in terms of experience. Institutional bias may have been introduced, as both PDs and APDs were invited to take the survey. A geographic bias may have been present, as relatively fewer PDs in the southern and western parts of the country responded (15%), and it is possible that PDs in those parts of the country view the PS differently. The very nature of qualitative research introduces biases into a data analysis, as each author comes into the project with preconceived ideas. We attempted to minimize this through triangulation of the data and calculation of the κ score to ensure appropriate agreement between coders. A reasonable next step would be to repeat this study on a larger scale and see if the themes identified in this study resonate with respondents across different specialties and disciplines.

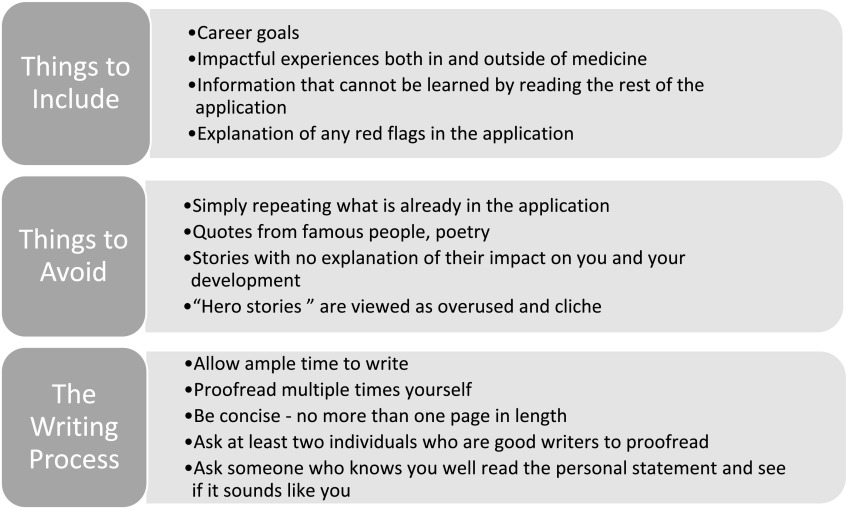

What applicants can take away from this study is that when writing their PS, they should keep the following in mind: make it personal, be honest and sincere, talk about something meaningful, be concise, and have someone else review and proofread it (Figure 3). This may help to alleviate the anxiety experienced by many trainees when writing their PS and make the PS a more meaningful part of their application, benefiting both applicants and training programs.

Figure 3.

Best practices for writing personal statements.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Concept and design: L.H., K.M.B., J.M., and G.B. Data analysis: L.H., W.G.C., and G.B. Drafting of the manuscript: L.H. and G.B. Critical review and editing of the manuscript: L.H., W.G.C., K.M.B., J.M., and G.B.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published as DOI: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2019-0004OC

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.National Resident Matching Program. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. Charting outcomes in the match, specialties matching service, appointment year 2018 [accessed 2019 Jul 15]. Available from: https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-Charting-Outcomes-SMS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell BH, Havas N, Derse AR, Holloway RL. Creating a residency application personal statement writers workshop: fostering narrative, teamwork, and insight at a time of stress. Acad Med. 2016;91:371–375. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNamee T. In defense of the personal statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:675. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, Beckerly R, Segal S. Have personal statements become impersonal? An evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinkle L, Carlos WG, Bosslet G. The good, the bad, and the ugly: personal statements from a program director’s perspective. Presented at the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors Annual Meeting. March 14, 2019, Albuquerque, NM. Awards Program; 6.

- 6.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bird AN, Martinchek M, Pincavage AT. A curriculum to enhance resilience in internal medicine interns. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:600–604. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00554.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Resident Matching Program. Specialties Matching Service; 2016. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey [accessed 2019 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arbelaez C, Ganguli I. The personal statement for residency application: review and guidance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:439–442. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segal S, Gelfand BJ, Hurwitz S, Berkowitz L, Ashley SW, Nadel ES, et al. Plagiarism in residency application essays. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:112–120. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-2-201007200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of American Medical CollegesERAS Integrity Promotion - Education Program; 2019 [accessed 2019 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-for-institutions/program-staff/policies/integrity-promotion

- 13.Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:32. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor T, Scott A. Do physicians prefer to complete online or mail surveys? Findings from a national longitudinal survey. Eval Health Prof. 2018;42:41–70. doi: 10.1177/0163278718807744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.