Abstract

To examine the feasibility and acceptability of an interactive video program of African American breast cancer survivor stories, we explored story reactions among African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer and associations between patient factors and intervention use. During a randomized controlled trial, patients in the intervention arm completed a baseline/pre-intervention interview, received the video intervention, and completed a post-intervention 1-month follow-up interview. Additional video exposures and post-exposure interviews occurred at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Multivariable linear mixed-effects models examined interview and clinical data in association with changes in minutes and actions using the program. After Exposure1, 104 of 108 patients allocated to the intervention reported moderate-to-high levels of positive emotional reactions to stories and identification with storytellers. Exposure1 mean usage was high (139 minutes) but declined over time (p< .0001). Patients receiving surgery plus radiation logged about 50 more minutes and actions over 12-month follow-up than patients receiving surgery only (p<.05); patients reporting greater trust in storytellers logged 18.6 fewer actions over time (p = .04). Patients’ topical interests evolved, with patients watching more follow-up care and survivorship videos at Exposure3. The intervention was feasible and evaluated favorably. New videos might satisfy patients’ changing interests.

Keywords: African American, breast cancer, health communication, randomized controlled trial, survivorship, survivor stories

Introduction

African American breast cancer survivors have poorer health outcomes compared with white breast cancer survivors(DeSantis, Ma, Goding Sauer, Newman, & Jemal, 2017).Identifying ways to improve quality of life (QOL) and promote follow-up care adherence (e.g., surveillance mammography) among African American breast cancer survivors may help reduce racial disparities in breast cancer outcomes(Banerjee, George, Yee, Hryniuk, & Schwartz, 2007).However, little is known about interventions to improve health-related outcomes in African American breast cancer survivors(Coughlin, Yoo, Whitehead, & Smith, 2015).

One promising strategy for improving health-related outcomes in African American women with breast cancer is using personal stories from other breast cancer survivors(Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007; M. Kreuter et al., 2007; M.W. Kreuter et al., 2008). Stories are a fundamental form of human interaction and provide a familiar, natural and comfortable way of giving and receiving information(M. Kreuter et al., 2007).Narratives can inform and motivate the public to engage in health promotion activities(Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007).While studies suggest benefits of narratives in health communication(Engler et al., 2016; Moon, Chih, Shah, Yoo, & Gustafson, 2017; Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2013), few focus on breast cancer survivorship in African American women(Coughlin et al., 2015),and the availability of online cancer survivor stories from underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups is lacking(Eddens et al., 2009).There is an unmet need for cancer-information resources tailored for newly diagnosed African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer(Haynes-Maslow, Allicock, & Johnson, 2016).

To address this need, we developed an interactive cancer-communication video program(Pérez et al., 2014)using broadcast-quality videos of African American breast cancer survivors telling their stories about being diagnosed and living with breast cancer(M.W. Kreuter et al., 2008; Matthew W. Kreuter et al., 2010).Compared to other forms of media such as print or audio, prior work (M. Kreuter et al., 2007) indicates that videos may shift the viewer’s attention to the storyteller’s characteristics and also may be most effective when the storytellers are perceived as likable or trustworthy.The survivor-stories video program included 207 video clips (1–3 minutes each; 5.4 hours in total) of personal stories from 35 African American breast cancer survivors to provide cancer-related information to African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. The stories were organized by 12 breast cancer topics focused on aspects of coping, social support, QOL, treatment side effects, healthcare experiences, and follow-up care(Pérez et al., 2014).Videos were programmed onto a Modbook (an Apple® MacBook® tablet computer developed by Axiotron, Inc.); stories could be browsed and viewed by simple, touch-screen user-driven navigation. The survivors varied by age and other characteristics to maximize the chances that women with breast cancer could identify with them(Oatley, 2002) and feel an emotional connection(Tan, 2013).

The survivor-stories video program was piloted using a small convenience sample of African American breast cancer survivors(Pérez et al., 2014)and was later used in a behavioral randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test the video program’s effect on QOL change over time and adherence to follow-up care (e.g., surveillance mammography and endocrine therapy, as indicated) in African American women with newly diagnosed, first primary breast cancer.Although the intervention was not significantly associated with QOL change(Schootman et al., 2020),evaluating the feasibility and acceptability of the survivor-stories video program has not been described.Because greater engagement, stronger emotional reactions,and greater identification are theorized pathways for communication effects on behaviors(McQueen & Kreuter, 2010),this paper describes patients’ intervention use, emotional reactions to stories, identification with storytellers, and their ratings of the video program’s usability. We also examined patient factors associated with intervention use. We expected patients to identify with storytellers, report positive reactions to stories, and favorably evaluate the intervention. We did not hypothesize how demographic, psychosocial, and clinical factors might be associated with intervention use, but explored potential relationships that could be addressed in considering changes to the intervention.

Methods

RCT Participants

Eligible, newly diagnosed patients were prospectively identified with help from their breast surgeons at the Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) and Saint Louis University School of Medicine. After Institutional Review Board approval (WUSM IRB #201102380), we recruited African American women ≥ 30 years old with first primary, noninvasive(stage 0) and invasive (stage I-III) breast cancer between December 2009 and December 2012 to participate in the RCT (registered at clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00929084).We included women who planned to receive unilateral mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery (BCS), and excluded women if they planned to receive bilateral mastectomies, since adherence to surveillance mammography was an outcome of interest in the RCT for which the intervention was developed.We excluded patients who were not African American, were non-English speaking, or were cognitively impaired based on weighted scores > 10 on the Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test(Katzman et al., 1983) administered to all patients ≥ 65 years of age.We excluded patients with a breast cancer history, who already would have had experiences like those discussed in the survivor stories. We also excluded patients diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, who have shorter expected survival than women with noninvasive or invasive, non-metastatic breast cancer (Dawood et al., 2008). Patients randomized to the control arm received standard of care (i.e., breast cancer treatments recommended by their treating physicians), and patients in the intervention arm received standard of care plus the survivor-stories video program.

RCT Procedures

Three specially trained study team coordinators obtained patients’ informed consent and randomized patients to the intervention or standard of care arm. None of the study coordinators happened to be African American. Neither the study team coordinators nor the patients were blinded to treatment arm; patients knew if they received the video program and study team coordinators trained patients in person how to use the program. Baseline (Interview1) was planned to coincide with each patient’s surgical post-operative visit or near the start of neoadjuvant therapy. Follow-up interviews were conducted one month after baseline (Interview2), and at six (Interview3), 12 (Interview4), and 24 (Interview5) months following patients’ definitive surgical treatment. Patients in the intervention arm were first exposed to the Modbook (Exposure1) after the baseline interview. The Modbook was delivered to patients for a second (Exposure2) and third (Exposure3) time approximately three weeks before each of Interview3 and Interview4, respectively. At each exposure, patients could spend as much time watching videos as they wanted.

Patients were trained at a mutually agreed upon time and location; they received a brief (~10 minute) in-person training to use the video program plus an instructional user guide to take home. Patients were informed that they would have approximately two weeks to use the video program at their home and could contact the study team by telephone with questions. About one week after training, study coordinators called patients to ask if they had watched stories or had any difficulty using the Modbook and informed patients that we would call again in one week to schedule both a time to return the Modbook and the next interview. Study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Measures

At each interview of the RCT, data collection from all patients included demographic information and validated measures of comorbidity, faith/spirituality, social support, history of depression, and symptoms of depressed mood. We also asked about use of various cancer-information and support resources. Clinical data, including stage, type of definitive surgical treatment, and receipt of neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments were collected from the medical record.

We used Katz’s validated adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index(Charlson, Pompei, Ales, & MacKenzie, 1987; Katz, Chang, Sangha, Fossel, & Bates, 1996) to measure patients’ history and presence of comorbidities; each condition is weighted with higher scores indicating greater comorbidity severity. We used the 15-item Systems of Belief Inventory(Holland et al., 1998) to measure patients’ religious/spiritual beliefs and practices; higher total scores indicate greater endorsement of religious/spiritual beliefs and practices and greater support received from their religious/spiritual community (Cronbach’s alpha at baseline = 0.88). The 19-item Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey(Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) measured availability of social support, if needed. Response choices range from “none of the time” (1) to “all the time” (5) with higher mean scores indicating greater perceived availability of social support(Cronbach’s alpha at baseline = 0.97). History of depression was measured at baseline using two items: “Has a doctor ever told you that you had depression?” and “Have you ever been treated for depression with medication or psychotherapy?” An affirmative response to either item indicated a history of depression. The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale(Radloff, 1977) measured the extent to which participants experienced depressive symptoms during the past week from “rarely or none of the time” (0) to “most or all of the time” (3), with higher total scores indicating greater depressed mood (Cronbach’s alpha at baseline = 0.92). Scores ≥16 were indicative of elevated depressed mood.

During the second, third and fourth interviews after each intervention exposure, for patients in the intervention arm only, we also asked about their emotional reactions to the stories, identification with storytellers, and usability of the video program. We assessed positive and negative emotional reactions using items from a prior study(McQueen & Kreuter, 2010; McQueen, Kreuter, Kalesan, & Alcaraz, 2011). Items were scored on a 5-point scale from “not at all” (1) to “extremely” (5); higher scores indicate more positive or more negative emotional reactions to watching the videos. Eleven previously used items evaluated participants’ level of identification with storytellers(i.e., perceived similarity to and trust in storytellers) (Matthew W. Kreuter et al., 2010; McQueen & Kreuter, 2010; McQueen et al., 2011). These items were scored on a 5-point scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5); higher scores indicate greater identification with the survivors. We also developed 18 usability items to evaluate the video program’s navigation, content, persuasiveness, and value.

Video usage (in minutes) was tracked within the video program based on the time and date for each action that a patient made while using the Modbook. Actions included turning the Modbook on and off and selecting stories and topics to watch.

Data Analysis

We describe the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, explore patient reactions to stories, and examine associations between intervention use and patient factors. We present the Modbook-usage results over 1-year follow-up of patients in the intervention arm who completed at least both the baseline interview and first video-program exposure. We examined the factor structure of items measuring emotional reactions to the stories and identification with storytellers using principal components analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation. We used Lautenschlager’s tables(Lautenschlager, 1989) based on parallel analysis criteria(Guadagnoli & Velicer, 1988; Velicer, 1976) to determine the number of factors given the sample size and number of items. We report Cronbach’s standardized alpha to measure the internal consistency of items loading on specific factors.

We report the mean (SD) number of minutes, actions, stories (video clips) watched, and days for each intervention exposure, including training. Because patients could watch each video multiple times, the total number of clips watched could exceed the total number of clips available for viewing. We also computed and report the total and most frequently selected story topics at each exposure.

One-way analyses of variance tested between-groups differences in video-program usage by categorical demographic and clinical variables. Chi-square tests examined associations among categorical variables of interest. Pearson product-moment correlations assessed correlations among Exposure1 usage data and continuous variables from Interview1, including age, comorbidity, psychosocial measures, extent of use of informational and support resources, and patients’ reactions after exposure to the stories and storytellers. Repeated-measures analyses of variance measured change in patients’ emotional reactions to survivor stories and identification with storytellers. To measure change in intervention use over time and identify variables independently associated with change in use, we ran separate multivariable linear mixed-effects models for each outcome (number of minutes and actions logged by the video program), including potential covariates that were associated with usage outcomes in bivariate tests.Two-tailed p-values < .05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC) and IBM® SPSS® version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

We consented and randomized 120 patients to the intervention arm of the RCT, of whom 108 enrolled (Supplemental Figure 1(Jarvandi et al., 2020)). Patients who enrolled did not differ significantly in age from patients who did not enroll (55.8 [9.7] vs. 58.2 [15.5]; p= .44).

Interview1 was completed a mean (SD) five (14) days from the date of a patient’s surgical post-operative visit or near the start of neoadjuvant therapy. After Interview1, one patient was lost to follow-up. The remaining 107 patients received Modbook training a mean four (3) days after Interview1, and patients kept the Modbook at home a mean 17 (9) days. Sample characteristics at baseline and Modbook usage data for the 107 patients completing both Interview1 and Exposure1 are shown in Table 1. After returning the Modbook, 104 patients completed Interview2 a mean 32 (12) days after Interview1. Patients were reminded how to use the Modbook before Exposure2 and Exposure3, and Interview3 and Interview4 were completed a mean seven (1) and 13 (1) months, respectively, following definitive surgical treatment.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and the mean (SD) number of minutes and actions logged using the intervention at Exposure1 among 107a patients who completed both the baseline interview and received the intervention at Exposure1

| Characteristics | N (%) | Number of Minutes Mean (SD) | p | Number of Actionsb Mean (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | 0.87 | 0.72 | |||

| Married/unmarried couple | 27 (25.2) | 151.3 (154.1) | 142.3 (137.7) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 40 (37.4) | 140.2 (121.8) | 126.6 (86.3) | ||

| Widowed | 17 (15.9) | 121.6 (80.3) | 137.5 (73.5) | ||

| Never married | 23 (21.5) | 133.9 (83.4) | 157.3 (101.8) | ||

| Education | 0.18 | 0.31 | |||

| <12th grade | 13 (12.1) | 83.1 (70.9) | 97.9 (63.8) | ||

| High school diploma/GED | 43 (40.2) | 151.0 (117.5) | 146.2 (88.4) | ||

| >High school | 51 (47.7) | 142.4 (124.5) | 143.2 (119.2) | ||

| Employment | 0.11 | 0.18 | |||

| Working at least part-time | 47 (43.9) | 156.1 (124.7) | 147.1 (91.4) | ||

| Retired/Homemaker | 18 (16.8) | 161.8 (139.4) | 166.8 (145.2) | ||

| Unemployed/unable to | 42 (39.3) | 109.2 (93.3) | 117.7 (90.2) | ||

| Incomec | 0.25 | 0.08 | |||

| <$25,000 | 64 (60.4) | 129.2 (114.0) | 128.5 (94.7) | ||

| $25,000–$75,000 | 33 (31.1) | 166.2 (131.0) | 170.4 (118.3) | ||

| >$75,000 | 9 (8.5) | 108.4 (82.3) | 100.4 (75.0) | ||

| Smoking history | 0.32 | 0.93 | |||

| Nonsmoker | 52 (48.6) | 151.1 (138.7) | 142.8 (119.2) | ||

| Former smoker | 25 (23.4) | 145.8 (102.3) | 135.6 (75.0) | ||

| Current smoker | 30 (28.0) | 111.3 (82.6) | 134.7 (93.1) | ||

| Cancer staged | 0.97 | 0.76 | |||

| DCIS (Stage 0) | 24 (22.4) | 134.2 (113.0) | 142.0 (89.7) | ||

| EIBC (Stage I, IIA) | 55 (51.4) | 141.3 (124.7) | 143.8 (114.4) | ||

| Late-stage (IIB, III) | 28 (26.2) | 137.2 (110.2) | 126.6 (89.3) | ||

| Definitive surgical treatmente | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| BCS | 70 (66.7) | 162.4 (122.9) | 159.0 (108.4) | ||

| Mastectomy | 35 (33.3) | 97.5 (93.5) | 104.5 (78.9) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.88 | 0.35 | |||

| Yesf | 53 (50.5) | 137.0 (106.1) | 129.5 (80.9) | ||

| No | 54 (49.5) | 140.3 (128.6) | 148.0 (120.0) | ||

| Radiation therapy | 0.11 | 0.10 | |||

| Yesg | 82 (76.6) | 148.8 (121.0) | 148.0 (107.8) | ||

| No | 25 (23.4) | 105.4 (99.9) | 109.0 (76.8) | ||

| Endocrine therapy | 0.03 | 0.06 | |||

| Yesh | 70 (65.4) | 156.6 (126.7) | 152.4 (109.8) | ||

| No | 37 (34.6) | 104.7 (89.6) | 113.2 (82.2) | ||

| History of depression | 0.36 | 0.39 | |||

| Yes | 36 (33.6) | 124.04 (116.0) | 126.8 (95.1) | ||

| No | 71 (66.4) | 146.10 (118.3) | 145.0 (106.1) | ||

| Elevated depressed mood | 0.77 | 0.53 | |||

| Yes | 38 (35.5) | 143.2 (113.1) | 147.3 (96.3) | ||

| No | 69 (64.5) | 136.2 (120.5) | 134.2 (106.1) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; GED, General Education Diploma; DCIS, ducta carcinoma in situ; EIBC, early-invasive breast cancer; BCS, Breast-conserving surgery

Patient characteristics not shown for one patient who was lost to follow-up after Interview1

Actions included turning the Modbook on and off and selecting specific stories and topics to watch

One patient refused to answer the survey item about income at Interview1

Cancer stage was determined by clinical staging in patients with locally advanced disease and by surgical pathology in patients with early-stage disease

Two women in the intervention arm of the study did not receive definitive surgical treatment

Received at any time over the 2-year study, including 19 who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Received at any time over the 2-year study, including two who received neoadjuvant radiation

Received at any time over the 2-year study, including seven who received neoadjuvant endocrine therapy

Of the 107 patients who received the intervention at Exposure1, 88 completed all three intervention exposures and interviews following each exposure (Supplemental Figure 1(Jarvandi et al., 2020)). A greater proportion of patients lost to follow-up after Exposure1 did not receive radiation therapy compared to patients who completed all intervention exposures (42.1% vs. 19.3%; p=.033). No other demographic, clinical, or psychosocial variables shown in Table1 differed significantly between patients lost to follow-up and patients who completed all three exposures and post-intervention interviews.

Intervention Usage

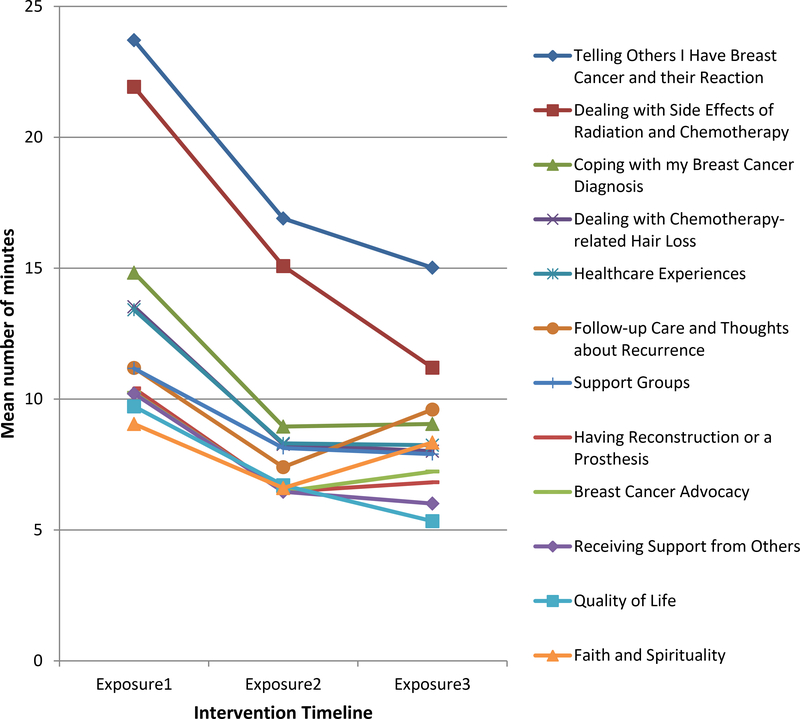

Usage data are displayed in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1. Patients completing all exposures had a greater mean (SD)number of minutes (149.7[117.7] vs. 87.6 [104.6]) and actions (149.5 [105.4] vs. 89.8 [70.7]) logged at Exposure1 compared to patients lost to follow-up after Exposure1 (each p<.05). Although intervention use declined after Exposure1 (Figure 1), patients spent a few more minutes watching stories in five topics at Exposure3 than Exposure2: Faith and Spirituality, Coping with my Breast Cancer Diagnosis, Breast Cancer Advocacy, Having Reconstruction or a Prosthesis, and Follow-up Care and Thoughts about Recurrence.

Figure 1.

Average number of minutes that patients watched survivor stories in each of the 12 topics at each intervention exposure.

We also examined the mean number of minutes that patients spent watching videos at Exposure1 in relation to the total minutes available for viewing in each topic (Supplemental Figure 2). Patients watched >50% of videos available in six of the 12 topics at Exposure1.

Overall, patients logged, on average, four hours (SD 3; range 0–18) watching stories across all three exposures (Supplemental Figure 3). Patients spent the most time watching stories in two topics, Telling Others I Have Breast Cancer and Dealing with Side Effects of Radiation and Chemotherapy, and the least time watching stories about Quality of Life, Having Reconstruction or a Prosthesis, Receiving Support from Others, and Faith and Spirituality.

Covariates of Intervention Use

Using Interview2 data (after Exposure1), PCA of the emotional reaction items yielded a 2-factor solution—four items measuring positive emotional reactions (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80) and eight items measuring negative emotional reactions (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). PCA of patients’ identification with storytellers also yielded a 2-factor solution—seven items measuring patients’ perceived similarity to storytellers (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89) and four items measuring trust in the storytellers as credible sources of cancer information (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79).

Patients reported moderate levels of positive emotional reactions, low levels of negative emotional reactions to the survivor stories, and high levels of similarity to and trust in the storytellers (Supplemental Figure 4). Patients’ negative emotional reactions to stories decreased significantly over time (p= .001). No significant change over time was observed for patients’ positive reactions to stories or for similarity to and trust in storytellers.

Baseline demographic, clinical, and psychosocial variables were associated with intervention use at Exposure1. Women who received breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and endocrine therapy spent more time watching stories at Exposure1 than patients who received mastectomy or did not receive endocrine therapy, respectively (Table 1). Additionally, women who received BCS logged more actions at Exposure1 compared with patients who received mastectomy (Table 1).

Trust in storytellers was negatively correlated with number of actions logged at Exposure1 (Table 2). Perceived similarity to the storytellers was positively correlated with positive emotional reactions to the stories and trust in storytellers and was negatively correlated with negative emotional reactions to the stories. Faith/spirituality and trust in storytellers were each positively correlated with positive emotional reactions.

Table2.

Pearson product-moment correlations among the continuous measures at baseline, patients’ level of engagement with survivor stories at Interview2, and number of minutes and actions using the intervention at Exposure1 (N = 107)

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of minutes | 0.91a | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.17 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.04 |

| Number of actions | 1.00 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.20b | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.09 | 0.00 |

| Age | 1.00 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.16 | −0.06 | −0.10 | 0.13 | −0.24b | 0.20b | |

| Social support | 1.00 | 0.29a | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.24b | −0.22b | ||

| Faith/spiritualityc | 1.00 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.27a | 0.15 | −0.04 | |||

| Perceived similarity to storytellersd | 1.00 | 0.56a | −0.20b | 0.52a | −0.04 | 0.06 | ||||

| Trust in storytellers as credible sources of informationd | 1.00 | −0.10 | 0.45a | −0.09 | 0.09 | |||||

| Negative emotional reactions to storiesd | 1.00 | −0.35a | −0.01 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Positive emotional reactions to storiesd | 1.00 | 0.06 | −0.04 | |||||||

| Exposure to information and support resources | 1.00 | −0.36a | ||||||||

| Comorbidity | 1.00 |

p< 0.01

p< 0.05

One patient refused to answer these items at Inteview1

Three patients who received the intervention at Exposure1 did not complete Interview2 where we measured patients’ level of engagement with survivor stories

Patients’ Evaluation of the Intervention

Patients favorably rated the video program’s usability (Supplemental Table 2). Responses were positive with regard to the video content (e.g., story length), and patients indicated they wanted to hear more stories (e.g., stories on other topics and more stories within our 12 story topics). Patients found the stories to be persuasive regarding the need to receive follow-up mammograms as recommended by their doctor; but the 13 patients taking endocrine therapy at Interview2 were split with regard to being convinced to take these medications as prescribed. Nearly all patients favorably evaluated their ability to navigate through the video program and search for videos,highly endorsed the value of the survivor stories, and would recommend the program to other breast cancer survivors.

Multivariable Linear Mixed-Effects Models of Change in Intervention Use

Separate adjusted mixed-effects models examined change in number of minutes and actions logged across the three exposures and variables associated with change in use. Time was modeled as a continuous variable with three values: 1, 6, and 12. Because a greater proportion of patients who received BCS (vs. mastectomy) received radiation therapy (92.9% vs. 42.9%; p <.001) and because patients with ductal carcinoma in situ(stage 0) do not receive chemotherapy, we created a variable to account for the extent of treatments received (surgery alone, surgery plus chemotherapy, surgery plus radiation, surgery plus radiation and chemotherapy) to use in the multivariable models.We included as covariates variables associated with minutes or actions at Exposure1(Table 1 and 2) plus age and employment status at baseline,as usage might vary by these variables in the presence of other variables in the model.One hundred two patients with complete data for all covariates and who received the intervention at Exposure1 were included in the analysis.

Table 3 shows that patients logged an average 7.7 fewer minutes and 7.1 fewer actions while watching stories over time (each p< .0001). Additionally, for each unit increase in patients’ trust in storytellers, patients logged an average 18.6 fewer actions (p= .04). No other variables were significantly associated with change in minutes or actions logged over time. Overall extent of treatment was not significant in either model; however patients who received surgery plus radiation logged 50 more minutes (p= .02) and 51 more actions (p= .01) than patients who received treatment with surgery only. Models including employment status as a time-varying variable did not have a statistically significant independent effect on change in number of minutes and actions over time (data not shown).

Table 3.

Results from separate adjusted linear mixed-effects models describing intervention use in number of both minutes used and actions taken by 102 patients who had complete data for all variables and received intervention exposure at Exposure1.

| Number of Minutes | Number of Actions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimate | SE | p | Parameter estimate | SE | p | |

| Month | −7.7 | 1.1 | <0.0001 | −7.1 | <0.0001 | |

| Treatment received | 0.13 | 0.07 | ||||

| Surgery only (reference) | 29.0 | 32.1 | 0.37 | 18.0 | 30.0 | 0.55 |

| Surgery + CT | 49.9 | 20.8 | 0.02 | 51.0 | 19.4 | 0.01 |

| Surgery + CT + RT | 35.3 | 20.9 | 0.09 | 29.3 | 19.5 | 0.13 |

| Received Endocrine Therapy | ||||||

| No (reference) | ||||||

| Yes | 18.8 | 14.4 | 0.19 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 0.34 |

| Trust In Storytellers | −15.3 | 9.8 | 0.12 | −18.6 | 9.1 | 0.04 |

| Age | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.62 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.55 |

| Employment Status | 0.08 | 0.23 | ||||

| Working at least part-time (reference) | ||||||

| Retired/Homemaker | 20.7 | 22.9 | 0.37 | 17.2 | 21.5 | 0.42 |

| Unemployed/Unable to work | −24.0 | 14.8 | 0.11 | −16.0 | 13.8 | 0.25 |

Discussion

We developed a survivor-stories video program to address an unmet need for cancer-information resources tailored for African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer (Haynes-Maslow et al., 2016).Our findings suggest that the video program, which provided information addressing a variety of concerns along the cancer continuum, can help meet this need and reinforced the notion that breast cancer survivors can be especially engaging, credible, and influential as messengers of cancer information(Eddens et al., 2009; M.W. Kreuter et al., 2008; Matthew W. Kreuter et al., 2010; McQueen & Kreuter, 2010; McQueen et al., 2011).

Intervention use was substantial with patients watching survivor stories for over four hours, on average, across all exposures. Patients overwhelmingly reported that the survivor stories were engaging and they identified with the storytellers. Patients also reported that the intervention was easy to use, watching the videos was worth their time and effort, and they would recommend the video program to other women with breast cancer.These results are indicative of the feasibility and acceptability of the survivor stories intervention for its targeted audience.

Patients’ topical interests evolved over the 12-month follow-up. At Exposure1, most viewed stories that dealt with treatment side effects and telling others about the breast cancer diagnosis. This may reflect needs identified in prior research, namely that cancer diagnoses are not openly discussed within some families(Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004),and that some patients might receive insufficient information about their disease(Bergenmar, Johansson, & Sharp, 2014) or have negative perceptions about necessary adjuvant treatments(Sheppard et al., 2010).

Intervention-usage decline is unsurprising given that no new stories were added during the trial. Decline might also reflect changing cancer-information needs after completing treatment. Under these conditions, communication science predicts that audience attention and exposure will generally decline(Hornik, 2002). Studies of online interventions also show that repeat use of a static site declines over time(Van ‘t Riet, Crutzen, & De Vries, 2010).Although time spent viewing videos in all topics declined after Exposure1, patients spent more time watching videos in some topics at Exposure3 compared with Exposure2, including stories in topics,Follow-up Care and Thoughts about Recurrence. Patients’ viewing choices suggest a clear arc of patient experience that is reflected in changing health information interests and needs after completing treatment(Matsuyama, Kuhn, Molisani, & Wilson-Genderson, 2013), which can be used to refine future interventions.

In the multivariable models, fewer actions were logged by women who reported greater levels of trust in the storytellers, potentially because these patients found the storytellers to be credible and they were satisfied with what they already heard about a given topic. Others have reported that patients with lower levels of trust in their physicians were more likely to search for health information on the Internet(Bell, Hu, Orrange, & Kravitz, 2011; Lee & Hornik, 2009), Also, patients who received surgery plus radiation made up 75% of patients in the intervention arm, and these patients logged more minutes and actions than patients who received surgery alone.Women with breast cancer receiving radiotherapy have a number of concerns about how treatment is administered and about its side effects(Halkett et al., 2010), which might explain why more minutes and actions were logged by patients who received radiation compared with patients who received surgery alone.

African American cancer patients may ask fewer questions than White patients during visits with their oncologist(Eggly et al., 2011). Many patients seek cancer information from other sources and a study of cancer patients searching for online narratives of other patients’ cancer experiences reported that patients most often selected videos with storytellers having similar characteristics as their own (e.g., age or time since diagnosis)(Engler et al., 2016). Breast cancer patients also have reported greater improvements in psychosocial adjustment if they received emotional support from survivors than from other newly diagnosed women with breast cancer (Moon et al., 2017).Health communication theories about narrative effects suggest that stories work best when audiences identify closely with the main characters and become emotionally engaged in their stories(Green, 2006; Green & Brock, 2000; Murphy et al., 2013). In our study, patient responses to the survivor stories aligned closely with this explanation. Patients liked and trusted the survivors whose stories they watched, and perceived the survivors were similar to themselves. Liking and similarity are key elements of identification in narrative and other forms of communication(Cohen, 2001), and both were associated with positive emotional reactions to the stories. Thus, interactive, computer-based interventions using survivor stories might be especially helpful for African American women with breast cancer, for whom such resources have been unavailable.

Clinical Implications

This intervention may be feasible to use in various settings, especially by newly diagnosed African American women with breast cancer with limited information and supportive resources in certain topic areas. For example, the videos could be used in clinic waiting rooms or disseminated broadly using social media. As the availability and usage of different forms of media continue to evolve, it is important to develop, test, and disseminate targeted interventions aimed at improving health-related outcomes for women with breast cancer and reducing racial disparities in breast cancer care and survival. In addition, as we viewed decline in usage of our static intervention over the course of treatment in the first year, we recommend changing videos over time to more closely match issues of concern to women with breast cancer at different times over the cancer continuum from diagnosis to survivorship.

Limitations

We report several limitations. Our intervention was designed specifically for African American women with breast cancer, and most patients were recruited from a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center, known for its leadership in conducting innovative clinical trials and community outreach to underserved populations. The generalizability of our findings to other racial/ethnic groups and to African American women receiving breast cancer treatment in other community settings may be limited. We do not know if the survivor-stories video program would be more or less well received and useful to women treated in other settings. The number of minutes of intervention use was logged from the moment the Modbook was turned on, regardless of whether any further action was made; thus, the number of minutes recorded might be an overestimation of the time a patient actually spent watching stories. However, the number of actions patients made was highly correlated with the number of minutes patients spent using the video program (r = .91), indicating that the Modbook was not, for the most part, simply turned on and left idle.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, these analyses are the first to examine use of a survivor-stories video intervention by African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer during and after treatment. It is also the first to examine change in video-program usage in relation to measures of patients’ demographic and clinical factors and to measure patients’ emotional reactions to and identification with the survivors in the videos. Patients endorsed the value of the intervention and found the video program easy to use and that the survivor stories were engaging. Results suggest that our video-program intervention was both feasible to use and acceptable among African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer and that the video program could be a powerful mechanism for disseminating cancer information and persuading patients to engage in recommended follow-up care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute under Grant [P50 CA095815; Principal Investigator: M. W. Kreuter] and the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant to the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri under Grant [P30 CA091842; Principal Investigator: T. Eberlein] for services provided by the Health Behavior, Communication and Outreach Core. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise. We thank our patient participants, the interviewers, and Ms. Lori Grove in Oncology Data Services at Washington University in St. Louis for assistance with data collection from the medical record. We also thank the physicians in addition to Dr. Margenthaler, who helped us recruit their patients for this study, including Drs. Timothy Eberlein, William Gillanders, Rebecca Aft, and Amy Cyr at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine and Dr. Theresa Schwartz and Pam Hunborg, RN, at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. The CONSORT diagram (Supplemental Figure 1) was used with permission from the publisher, Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, … Hills D (2004). Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 13(6), 408–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee M, George J, Yee C, Hryniuk W, & Schwartz K (2007). Disentangling the effects of race on breast cancer treatment. Cancer, 110(10), 2169–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, Hu X, Orrange SE, & Kravitz RL (2011). Lingering questions and doubts: online information-seeking of support forum members following their medical visits. Patient Education and Counseling, 85(3), 525–528. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergenmar M, Johansson H, & Sharp L (2014). Patients’ perception of information after completion of adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs, 18(3), 305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales K, & MacKenzie CR (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40, 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (2001). Defining Identification: A Theoretical. Look at the Identification of Audiences. With Media Characters. Mass Communication and Society, 4(3), 245–264. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS, Yoo W, Whitehead MS, & Smith SA (2015). Advancing breast cancer survivorship among African-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 153(2), 253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3548-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood S, Broglio K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN, & Giordano SH (2008). Trends in survival over the past two decades among white and black patients with newly diagnosed stage IV breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 26(30), 4891–4898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis CE, Ma J, Goding Sauer A, Newman LA, & Jemal A (2017). Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 67(6), 439–448. doi: 10.3322/caac.21412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddens KS, Kreuter MW, Morgan JC, Beatty KE, Jasim SA, Garibay L, … Jupka KA (2009). Disparities by race and ethnicity in cancer survivor stories available on the web. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(4). doi: 10.2196/jmir.1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggly S, Harper FWK, Penner LA, Gleason MJ, Foster T, & Albrecht TL (2011). Variation in Question Asking during Cancer Clinical Interactions: a Potential Source of Disparities in Access to Information. Patient Education and Counseling, 82(1), 63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler J, Adami S, Adam Y, Keller B, Repke T, Fugemann H, … Holmberg C (2016). Using others’ experiences. Cancer patients’ expectations and navigation of a website providing narratives on prostate, breast and colorectal cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(8), 1325–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC (2006). Narratives and Cancer Communication. Journal of Communication, 56, S163–S183. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00288.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, & Brock TC (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnoli E, & Velicer W (1988). Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), 265–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkett GK, Kristjanson LJ, Lobb E, O’Driscoll C, Taylor M, & Spry N (2010). Meeting breast cancer patients’ information needs during radiotherapy: what can we do to improve the information and support that is currently provided? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl), 19(4), 538–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes-Maslow L, Allicock M, & Johnson LS (2016). Cancer Support Needs for African American Breast Cancer Survivors and Caregivers. J Cancer Educ, 31(1), 166–171. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0832-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinyard LJ, & Kreuter MW (2007). Using Narrative Communication as a Tool for Health Behavior Change: A Conceptual, Theoretical, and Empirical Overview. Health Education & Behavior, 34(5), 777–792. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, Kash KM, Passik S, Gronert MK, Sison A, Lederberg M, … Fox B (1998). A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psycho-Oncology, 7, 460–469. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik RC (2002). Public Health Communication: Evidence for Behavior Change. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvandi S, Pérez M, Margenthaler J, Colditz GA, Kreuter MW, & Jeffe DB (2020). Improving Lifestyle Behaviors After Breast Cancer Treatment Among African American Women With and Without Diabetes: Role of Health Care Professionals. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaaa020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, & Bates DW (1996). Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Medical Care, 34(1), 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, & Schimmel H (1983). Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration test of cognitive impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter M, Green M, Cappella J, Slater M, Wise M, Storey D, … Woolley S (2007). Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: A framework to guide research and application. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(3), 221–235. doi: 10.1007/bf02879904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Buskirk TD, Holmes K, Clark EM, Robinson L, Si X, … Mathews K (2008). What makes cancer survivor stories work? An empirical study among African American women. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 2(1), 33–44. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0041-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, Kalesan B, Rath S, Richert M, … Clark EM (2010). Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Education and Counseling, 81, Supplement 1(0), S6–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager GJ (1989). A comparison of alternatives to conducting Monte Carlo analyses for determining parallel analysis criteria. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24(3), 365–395. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2403_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CJ, & Hornik RC (2009). Physician trust moderates the Internet use and physician visit relationship. Journal of Health Communication, 14(1), 70–76. doi: 10.1080/10810730802592262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama RK, Kuhn LA, Molisani A, & Wilson-Genderson MC (2013). Cancer patients’ information needs the first nine months after diagnosis. Patient Education and Counseling, 90(1), 96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, & Kreuter MW (2010). Women’s cognitive and affective reactions to breast cancer survivor stories: a structural equation analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 81 Suppl(81), S15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Kreuter MW, Kalesan B, & Alcaraz KI (2011). Understanding narrative effects: the impact of breast cancer survivor stories on message processing, attitudes, and beliefs among African American women. Health Psychology, 30(6), 674–682. doi: 10.1037/a0025395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon T-J, Chih M-Y, Shah DV, Yoo W, & Gustafson DH (2017). Breast Cancer Survivors’ Contribution to Psychosocial Adjustment of Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer Patients in a Computer-Mediated Social Support Group. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(2), 486–514. doi: 10.1177/1077699016687724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2013). Narrative versus Nonnarrative: The Role of Identification, Transportation, and Emotion in Reducing Health Disparities. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 116–137. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oatley K (2002). Emotions and the story worlds of fiction. Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations, 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez M, Sefko JA, Ksiazek DN, Golla B, Casey C, Margenthaler JA, … Jeffe DB (2014). A novel intervention using interactive technology and personal narratives to reduce cancer disparities: African American breast cancer survivor stories. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 8, 21–30. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schootman M, Perez M, Schootman JC, Fu Q, McVay A, Margenthaler J, … Jeffe DB (2020). Influence of built environment on quality of life changes in African-American patients with non-metastatic breast cancer. Health & Place, 63, 102333. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard VB, Williams KP, Harrison TM, Jennings Y, Lucas W, Stephen J, … Taylor KL (2010). Development of Decision Support Intervention for Black Women with Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19(1), 62–70. doi: 10.1002/pon.1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, & Stewart AL (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ES (2013). Emotion and the structure of narrative film: Film as an emotion machine: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van ‘t Riet J, Crutzen R, & De Vries H (2010). Investigating Predictors of Visiting, Using, and Revisiting an Online Health-Communication Program: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(3), e37. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF (1976). Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika, 41(3), 321. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.