Abbreviations

- CDUS

color and spectral Doppler ultrasound

- CEUS

contrast‐enhanced ultrasound

- CHA

common hepatic artery

- CTA

computed tomography angiography

- HAS

hepatic artery stenosis

- HAT

hepatic artery thrombosis

- IV

intravenous

- IVC

inferior vena cava

- LHA

left hepatic artery

- MPV

main portal vein

- MRA

magnetic resonance angiography

- PV

portal vein

- RHA

right hepatic artery

Post–liver transplant vascular complications have an overall incidence rate of 7% to 30%, leading to increased morbidity and decreased graft survival 1 (Table 1). Most feared in the immediate posttransplant setting is hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT), which is associated with biliary damage, allograft failure, the need for retransplantation, and a high mortality rate of 20% to 60%. 2 , 3 Complications involving the portal and hepatic venous systems are less common. Acute posttransplant portal vein (PV) thrombosis and stenosis can lead to portal hypertension, hepatic dysfunction, and the need for surgical revision or thrombectomy. 2 Hepatic venous thrombosis and stenosis are associated with increased morbidity because of venous congestion, putting the allograft at risk. As such, early, accurate detection of vascular complications is critical to reduce allograft dysfunction and failure.

TABLE 1.

Incidence of Post–Liver Transplant Vascular Complications

| Vascular Complication | Reported Incidence Rate |

|---|---|

| HAT | 2%‐16% |

| HAS | 0.8%‐9% |

| Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm | ~2% |

| PV stenosis | 2%‐10% |

| PV thrombosis | 1%‐2% |

| Venous/IVC stenosis | ~1% |

| Venous/IVC thrombosis | ~1% |

Conventional Imaging Modalities For Posttransplant Hepatic Vasculature Evaluation

Immediate postoperative evaluation of the graft with B‐mode, color, and spectral Doppler ultrasound (CDUS) varies depending on regional practices, with some centers routinely performing daily scans during the first posttransplant week and other centers performing scans only in the setting of graft dysfunction. CDUS is noninvasive and associated with minimal risk. Posttransplant CDUS, however, can be technically challenging and time‐consuming, with one study showing an average scan time of 27.4 minutes. 4 In addition, CDUS can yield false‐positive results, especially in the first postoperative week when abnormal or absent waveforms may be encountered in otherwise normal vessels because of hepatic edema or systemic hypotension. 3 These false‐positive results may lead to unnecessary invasive imaging. False‐negative results with CDUS are more commonly seen in the late posttransplant period after collaterals have developed in response to chronic hepatic artery occlusion. 3 , 5

When CDUS fails to demonstrate flow, further imaging is indicated to confirm and evaluate the extent of thrombosis. Traditionally, these diagnostic studies include computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and catheter angiography, 5 and all require intravenous (IV) contrast administration. Iodinated IV contrast used with CTA and angiography poses a significant risk in this patient population who suffer from a high incidence of posttransplantation acute kidney injury reported to be up to 40.8%. 6 Both iodinated and gadolinium‐based IV contrast agents are also associated with allergic reactions. The longer examination times with MRA may make this examination inappropriate for ICU patients. Finally, catheter angiography, the gold standard modality to evaluate for vascular abnormalities, poses a procedural risk.

Contrast‐enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has become increasingly accepted as the initial evaluation, after an abnormal CDUS examination, because of its accuracy and reliability in diagnosing vascular complications after liver transplantation. 7 , 8 Its advantages over CDUS include decreased scan time, improved hepatic vasculature visualization, and improved evaluation of patency in those arteries exhibiting no flow on CDUS. 4 , 7

CEUS improves flow visualization in hepatic vessels by the use of intravascular microbubbles. Ultrasound contrast microbubbles are red blood cell–sized lipid shells containing inert gas, which enhance acoustic backscatter created by the impedance differences between gas and blood. The gas within the microbubbles is eliminated through the lungs, making the contrast safe in patients with renal dysfunction, and there are few contraindications. 9 The most common side effects reported are headache and nausea in 2% of patients, and allergic reactions are very uncommon. Contrast microbubbles are given through a peripheral IV, 20 gauge or larger, but may also be administered through central lines and port systems. 9

When CDUS fails to show flow within the hepatic arteries, CEUS may demonstrate normal flow within these vessels (Fig. 1). For the evaluation of HAT, CEUS allows clear visualization of the hepatic artery with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy to almost 100% as compared with a sensitivity of 82% to 92% with CDUS. 2 , 7 Therefore, the use of CEUS after an abnormal CDUS can avoid more invasive imaging. In one study, CEUS avoided angiography in 62.9% of cases when HAT was suspected on CDUS. 7 At our institution, over a 2‐year period during which CDUS findings concerning for vascular complications prompted CEUS, 11 of 13 patients had a normal CEUS, obviating the need for more invasive procedures (unpublished data). Of the remaining two patients, one patient’s CEUS confirmed abnormal hepatic arterial flow ultimately found to be due to recipient hepatic arterial dissection (Fig. 2). In the second patient, CEUS confirmed left PV thrombus (Fig. 3). In the evaluation of hepatic artery stenosis (HAS), CEUS can help detect this complication by producing angiographic images. 9 The sensitivity and specificity of CEUS in the evaluation of stenosis has been reported at 92.3% and 87.5%, respectively. 7 Although CEUS has not been shown to be significantly better than CDUS at detecting HAS, CEUS can help decrease false‐positive results and increase diagnostic confidence. 9 CEUS can also facilitate evaluation of the degree and type of stenosis. 7

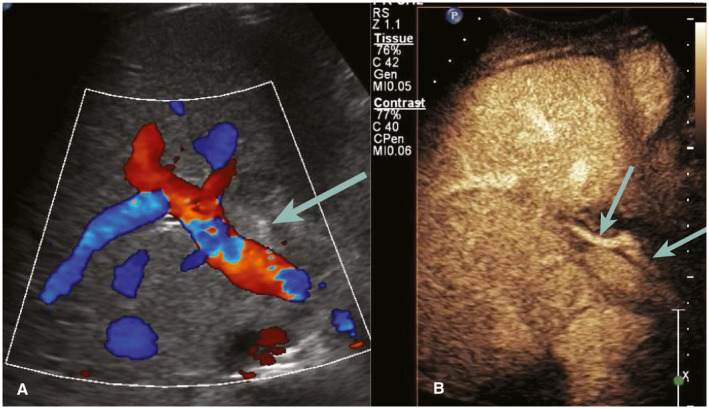

FIG 1.

Postoperative day 1. (A) CDUS shows no visible flow in the CHA (arrow), RHA, and LHA. (B) CEUS performed immediately after CDUS shows normal flow and patency of all arterial segments; CHA and RHA are shown (arrows). The patient required no further imaging.

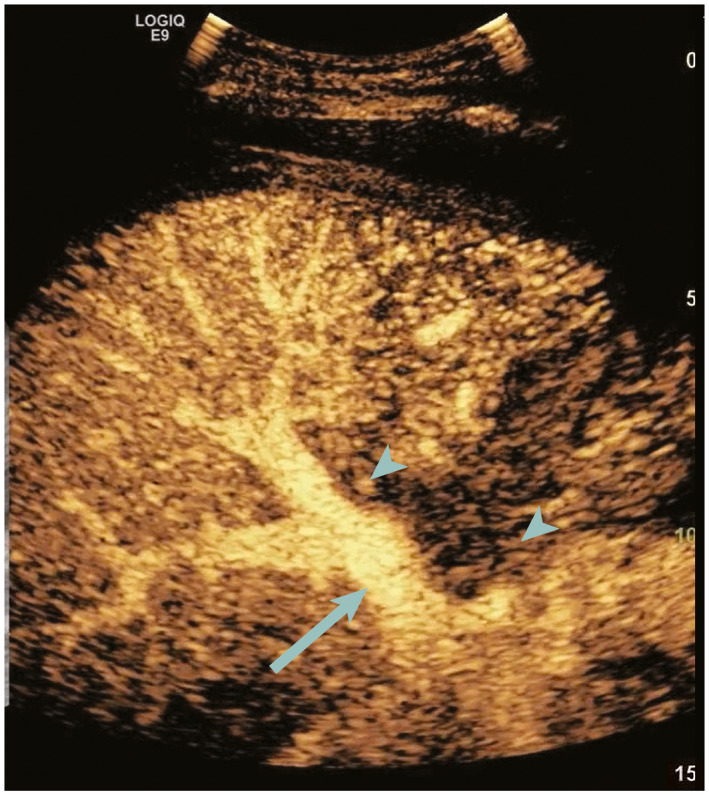

FIG 2.

CDUS obtained on postoperative day 2 showed no detectable hepatic artery flow (not shown). CEUS performed immediately after shows normal enhancement of the PV (arrow) with late and weak enhancement of the CHA and RHA (arrowheads). Patient was taken immediately to surgery where dissection of the recipient hepatic artery was found resulting in a severe HAS. The artery was revised, and the patient responded well.

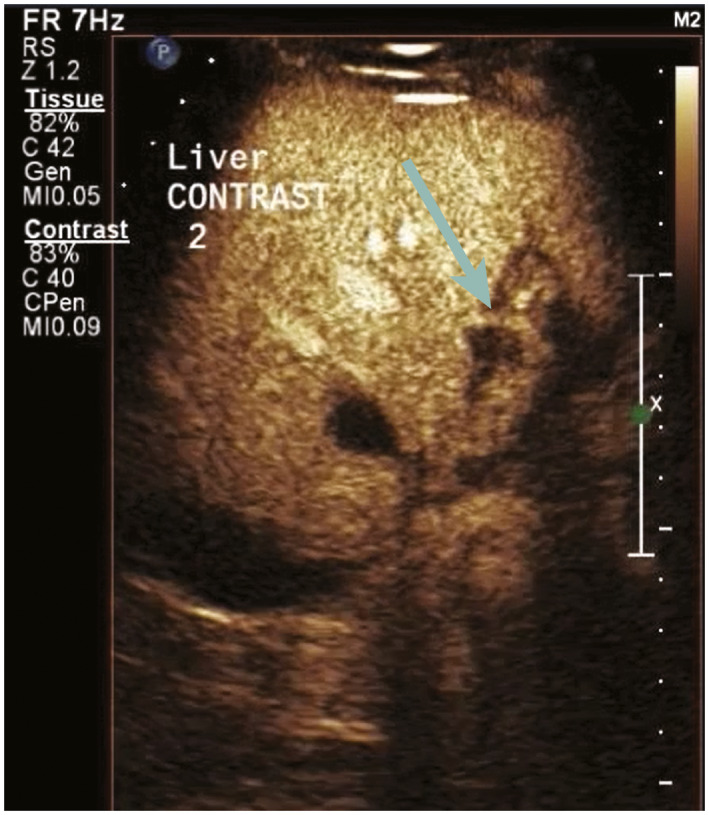

FIG 3.

CDUS obtained on postoperative day 1 showed no flow in the left PV (not shown). CEUS performed immediately after shows a normal LHA (arrow), but no flow in the adjacent left PV. This was confirmed at follow‐up MRI 1 year later, at which time biliary strictures had developed.

With hepatic vein thrombosis/stenosis, CDUS may reveal loss of phasicity or reversed flow, whereas CEUS is more specific, showing absent or decreased contrast enhancement. 7 , 9 CEUS also significantly improves PV visualization detecting stenosis as an abrupt change in caliber or acute thrombosis as absence of flow (Fig. 3). CEUS may be particularly helpful when CDUS is suspicious or equivocal for PV thrombosis (Fig. 4). CEUS also depicts other immediate postsurgical complications, such as perihepatic fluid collections and hepatic parenchymal infarcts. Infarction is seen on CEUS as geographic areas of absent or severely diminished perfusion. 9

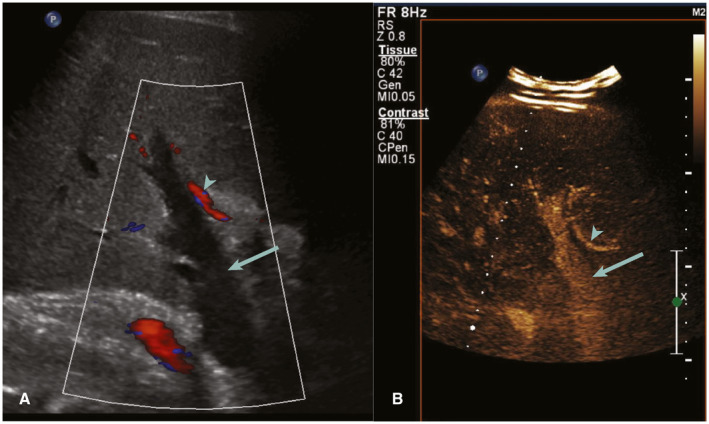

FIG 4.

Postoperative day 30 presenting with hypotension. (A) CDUS shows absent flow in the PV (arrow) with normal flow in the hepatic artery (arrowhead). (B) CEUS performed immediately after shows patency of the PV (arrow) and hepatic artery (arrowhead), confirming a false‐positive CDUS study.

Although more accurate than CDUS, CEUS suffers technical limitations, such as poor bolus preparation and poor setup of the scanner. Similar to CDUS, factors that affect visualization include wound dressings, limited patient mobility, and large body habitus. 9 Visualization can also be impaired by gas from postoperative pneumoperitoneum or overlying bowel. 9 Both modalities can be limited in the evaluation of central or deeper vessels and may not clearly visualize the aorta, celiac trunk, or hepatic artery origin. 10 In addition, the arterial anastomosis may be difficult to identify discretely along the course of the opacified artery. When these central structures are well seen, the resolution may be poor such that quantification of a stenosis is difficult. Further, in the case of complex arterial reconstructions, following the tortuous arteries to evaluate and understand the anatomy may be difficult, and the radiologist’s knowledge of the donor and recipient anatomy is helpful in accurate assessment. Conversely, CTA and angiography offer superb visualization of the entire arterial system and are able to detect and quantify stenosis, as well as depict complex anatomy in three dimensions. As a result, mastery of technical skills by the radiologist plays an important role in accurate utility of CEUS and diagnosis of posttransplant vascular complications.

Conclusion

Post–liver transplant vascular complications remain a significant source of morbidity and possible graft loss, necessitating rapid, accurate diagnosis and expedited management for graft salvage. CEUS is easy, safe to use, and has increased diagnostic accuracy of vascular complications as compared with conventional ultrasound. Given the diagnostic advantages, CEUS is an emerging tool that can be used after an abnormal CDUS and prior to more invasive imaging or treatment.

Potential conflict of interest: B.R.F. consults for Bot Image, Inc. and Elsevier.

References

- 1. Chen J, Weinstein J, Black S, et al. Surgical and endovascular treatment of hepatic arterial complications following liver transplant. Clin Transplant 2014;28:1305‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Teegen EM, Denecke T, Eisele R, et al. Clinical application of modern ultrasound techniques after liver transplantation. Acta Radiol 2016;57:1161‐1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baheti AD, Sanyal R, Heller MT, et al. Surgical techniques and imaging complications of liver transplant. Radiol Clin North Am 2016;54:199‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hom BK, Shrestha R, Palmer SL, et al. Prospective evaluation of vascular complications after liver transplantation: comparison of conventional and microbubble contrast‐enhanced US. Radiology 2006;241:267‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi EK, Lu DSK, Park SH, et al. Doppler US for suspicion of hepatic arterial ischemia in orthotopically transplanted livers: role of central versus intrahepatic waveform analysis. Radiology 2013;267:276‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thongprayoon C, Kaewput W, Thamcharoen N, et al. Incidence and impact of acute kidney injury after liver transplantation: a meta‐analysis. J Clin Med 2019;8:372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ren J, Wu T, Zheng B‐W, et al. Application of contrast‐enhanced ultrasound after liver transplantation: current status and perspectives. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1607‐1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee SJ, Kim KW, Kim SY, et al. Contrast‐enhanced sonography for screening of vascular complication in recipients following living donor liver transplantation. J Clin Ultrasound 2013;41:305‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lyshchik A, Dietrich CF, Sidhu PS, et al. Fundamentals of CEUS. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Herold C, Reck T, Ott R, et al. Contrast‐enhanced ultrasound improves hepatic vessel visualization after orthotopic liver transplantation. Abdom Imaging 2001;26:597‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]