Abstract

Background and study aims Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is widely performed for superficial esophageal cancer, but stricture after extensive resection is a major clinical problem. Using an ultrathin endoscope would enable endoscopists to approach lesions beyond the stricture. We evaluated the feasibility of an ultrathin endoscope for esophageal ESD.

Methods To perform ESD with an ultrathin endoscope, we developed a transparent hood and ESD knife. A total of 24 esophageal ESDs were performed by two endoscopists with excised and live porcine esophaguses. A GIF-Q260 J and Dual knife were used in the conventional group and the GIF-XP260NS and a newly developed knife were used in the ultrathin group. En bloc resection rates, perforation rates, and procedure times were compared.

Results All 24 lesions were resected en bloc without perforation. The mean procedure time was longer in the ultrathin group, although not significantly so (274.3 ± 81.8 s vs 435.8 ± 313.9 s, respectively; P = 0.22).

Conclusion Although the procedure time was longer in the ultrathin group, en bloc resection was performed without any perforation. The findings indicate that esophageal ESD with an ultrathin endoscope is feasible.

Introduction

Endoscopy is the standard treatment for superficial gastrointestinal tumors without risk of lymph node metastasis. Endoscopic treatment has progressed from conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) to endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) 1 . The advantages of ESD are its high complete resection rate, low local recurrence risk, and precise pathological diagnosis. However, the disadvantages are its high rate of complications, such as perforation and bleeding.

The risk of esophageal ESD includes stricture in addition to perforation and bleeding. Circumferential lesions can be resected with ESD, but the incidence of postoperative stricture is high. Attempts to prevent postoperative stricture have involved oral administration of steroids, local injection, and use of polyglycolic acid (PGA) sheets, but none of these are perfect and stricture sometimes occurs 2 3 4 5 . Occasionally, metachronous superficial esophageal cancer is found beyond the stricture and balloon dilation is required before ESD. However, we sometimes experience severe stricture that conventional endoscopy cannot pass even after balloon dilation. In this situation, we sometimes perform ESD without a transparent hood. But the visual field without a transparent hood during dissection is poor and the possibility of adverse events (AEs) such as perforation is thought to be high. Use of an ultrathin endoscope could enable endoscopists to approach an esophageal lesion beyond the stricture.

In recent years, ultrathin endoscopes have been widely used in screening endoscopy 6 7 . These scopes’ small diameter is a major advantage in reducing patient pain. However, it has not been conventionally possible to use an ultrathin endoscope for ESD because of the lack of a dedicated device for treatment. We have therefore developed a transparent hood and ESD knife to enable ESD with an ultrathin endoscope, and we evaluated the feasibility of use of the ultrathin endoscope for esophageal ESD.

Methods

Device development

In collaboration with Yasui Co., Ltd. (Miyazaki, Japan), we developed a transparent hood for ultrathin endoscopes ( Fig. 1 ). The inner diameter of the hood was 5.6 mm and the outer diameter was 6.9 mm; elastomer was the material used.

Fig. 1.

Newly developed transparent hood. a Overall view of the new transparent hood. b The ultrathin endoscope mounted with the transparent hood.

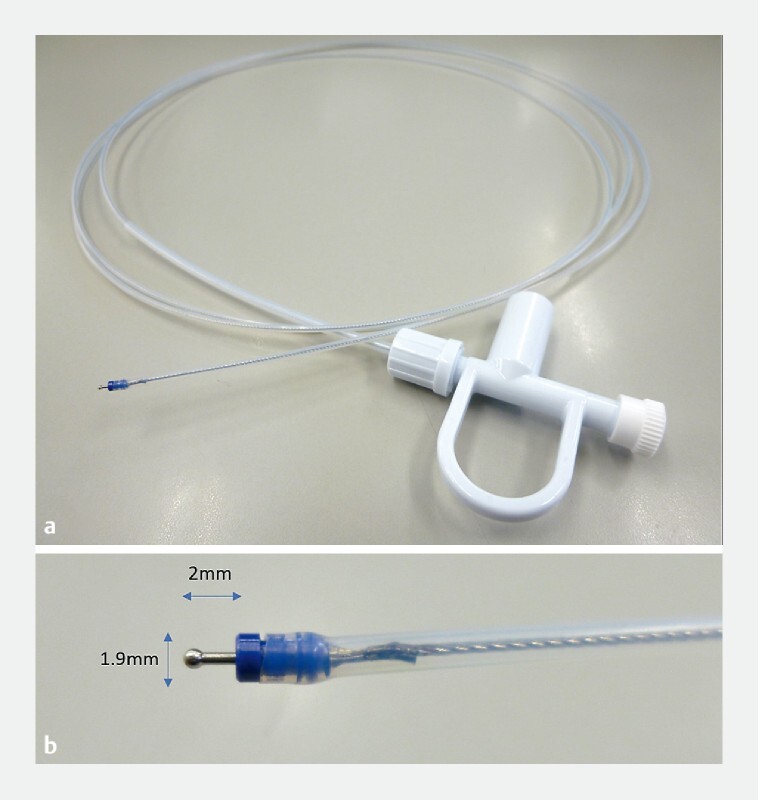

Also, in collaboration with Yamashina Seiki Co., Ltd. (Shiga, Japan), we developed an ESD knife that can be used with ultrathin endoscopes ( Fig. 2 ). The knife tip had a maximum diameter of 1.9 mm and protruded 2 mm from the sheath tip.

Fig. 2.

New ESD knife used in this study. a Overall view of the new ESD knife. b The knife has a maximum diameter of 1.9 mm and protrudes 2 mm from the sheath tip.

Animal model

To verify the feasibility of use of an ultrathin endoscope for esophageal ESD, experiments were performed using excised porcine esophagus (Experiment 1) and live porcine esophagus (Experiment 2). These experiments were conducted with the approval of the Animal Experiments Committee of our hospital.

In Experiment 1, the excised esophagus was stored in a plastic case. In Experiment 2 using live porcine esophagus, a 20-kg sow was sedated under general anesthesia.

In the conventional group, GIF-Q260 J endoscope, Dual knife, and a normal size transparent hood (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used. In the ultrathin group, GIF-XP260NS ultrathin endoscope (Olympus) with the newly developed transparent hood attached (Yasui Co., Ltd.) and the new small-diameter knife (Yamashina Seiki) were used.

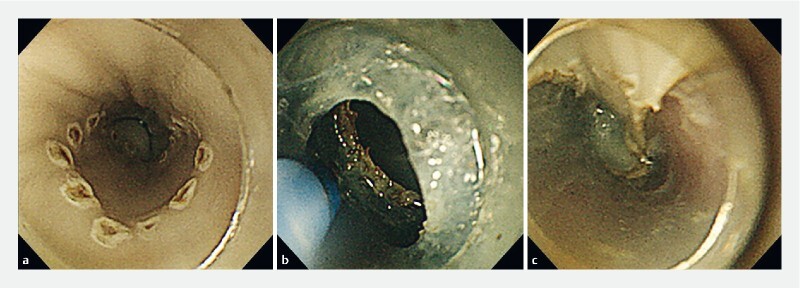

In each experiment, a virtual lesion with a diameter of 15 mm was created and ESD was performed by two endoscopists alternately using the ultrathin endoscope ( Fig. 3 ) and the conventional endoscope. ESD was performed 12 times each in Experiments 1 and 2, for a total of 24 times. The evaluation items were en bloc resection rate, perforation rate, and mean procedure time. Procedure time was defined as the time from the start of incision to excision of the specimen.

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic image of ESD with an ultrathin endoscope. a Endoscopic image of marking for a virtual lesion 15 mm in diameter. b Endoscopic image during submucosal dissection. c Endoscopic image after en bloc resection achieved without perforation.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the unpaired t-test, chi-squared test, Fisher’s test, or Mann-Whitney U-test as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (SPSS IBM statistics).

Results

All lesions were resected en bloc without any perforation or muscle injury. The mean procedure time was 274.3 ± 81.8 s in the conventional group and 435.8 ± 313.9 s in the ultrathin group, which was not significantly different ( P = 0.22) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Comparison between use of a conventional endoscope and the ultrathin endoscope for esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection.

| Conventional group | Ultrathin group | P value | |

| En bloc resection rate (%, n/n) | 100 (12/12) | 100 (12/12) | |

| Perforation rate (%, n/n) |

0 (0/12) | 0 (0/12) | |

| Mean procedure time (s ± SD) | 274.3 ± 81.8 | 435.8 ± 313.9 | 0.22 |

In Experiment 1, the mean procedure time was similar between the two groups, at 232.2 ± 36.9 seconds in the conventional group and 251.7 ± 65.3 seconds in the ultrathin group. In Experiment 2, the mean procedure time was longer in the ultrathin group, although not significantly so (316.5 ± 95.3 seconds vs 619.8 ± 362.2 seconds, respectively; P = 0.20) ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Mean procedure time for each experiment.

| Conventional group | Ultrathin group | P value | |

| Experiment 1 (s±SD) | 232.2±36.9 | 251.7±65.3 | 0.87 |

| Experiment 2 (s±SD) | 316.5±95.3 | 619.8±362.2 | 0.20 |

Discussion

ESD for esophageal cancer is widely performed and has been applied to large lesions in recent years. With technological advancements, the rates of AEs such as perforation and bleeding have decreased. However, stricture after extensive resection has become a major clinical issue. Oral steroids and local injection are commonly used to prevent stricture 2 3 , but these come with risks of side effects such as diabetes, infection, and perforation. In cases where steroids cannot be used, new treatments such as PGA sheets, stent insertion 8 , and bioabsorbable sheets have been proposed, but none of these can completely prevent stricture. The use of an ultrathin endoscope would allow for endoscopic observation and treatment beyond the stenotic site, which is advantageous for patients with stricture.

Esophageal cancer has a high probability of being metachronous 9 , and a new superficial cancer is often found on the anal side of the stricture. Accordingly, an ultrathin endoscope is desirable, and we therefore decided to develop the dedicated device.

The ultrathin endoscope is less invasive for patients and can be inserted trans-nasally to reduce the gag reflex. And it is widely used mainly in screening endoscopy. Also, with improvements in image resolution, the ultrathin endoscope would be very useful in diagnosis of early gastrointestinal cancer. Indeed, it has been reported that the detection rate for early-stage cancer using ultrathin endoscopes is comparable to that using a conventional endoscope 6 7 . The ultrathin endoscope has also proved useful in therapeutic endoscopy and is used in clinical practice, especially when inserting ileus tubes 10 . However, it has not been commonly used in endoscopic resection such as ESD or EMR mainly because there has been no dedicated treatment device to date. The development of a dedicated device could lead to increased use of the ultrathin endoscope for ESD.

There are several reports and merits of ultrathin endoscope for ESD 11 12 13 . One is that it enables treatment beyond a narrow lumen or stricture. Another is that entering the submucosal layer is easier than when using a conventional endoscope. In recent years, a method has been proposed for ESD that involves creating tunnels and pockets in the submucosal layer 14 , yet it is important to enter the submucosal space quickly. In this respect, ESD with an ultrathin endoscope has a considerable advantage. We sometimes use the ultrathin endoscope in pharyngeal ESD because of the narrow working space 15 . Dedicated devices such as an ESD knife and transparent hood are desirable and could also be applied to pediatric endoscopy. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for achalasia is becoming more common worldwide and the use of an ultrathin endoscope may be useful in making POEM safer for pediatric achalasia 16 . In addition, nasal insertion means that the sedative dose used during endoscopic treatment could be reduced. Sedative use should be minimized in older patients, and ESD with an ultrathin endoscope may be beneficial for this.

There are some disadvantages to using the ultrathin endoscope for ESD. One is its poor suction function, and hemostasis may be difficult when bleeding occurs. Currently, the forceps channel of the ultrathin endoscope developed by Fujifilm (EG-L580NW7, EG-6400N) has a diameter of 2.4 mm and there are corresponding hemostatic forceps (RAICHO2: Kaneka Medix Corporation, Osaka, Japan) and a clip (SAIKEI: Kaneka Medix Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Thus, the development of an ultrathin endoscope with a large channel diameter is desirable. In this feasibility study, we did not experience massive bleeding requiring use of hemostatic forceps. In the next trial, we will evaluate the technical difficulty of hemostasis during the ESD procedure with ultrathin endoscope. Another problem is that the scope is unstable because the endoscope is so thin. It is, therefore, important to enter the submucosal space as soon as possible to stabilize the scope during treatment in the submucosal tunnel. Another major disadvantage is the lack of a water-jet function. Currently, most ESD procedures are performed using an endoscope with a water-jet function. Development of an ultrathin endoscope with a water-jet function is anticipated. It is important to prepare for AEs such as intraoperative bleeding and perforation. The devices that can be used with the ultrathin endoscope are limited. Therefore, endoscopists should preoperatively check the types of hemostatic forceps and clips that can be used with the ultrathin endoscope.

In this study, the procedure time for Experiment 1 was deemed equivalent between two groups. However, for Experiment 2, there was no significant difference but the procedure time in the ultrathin group was longer. This was because a clear endoscopic view could not be created due to bleeding or mucus. In actual clinical practice, ESD needs to be performed in various situations, so securing a clearer visual field is needed in ESD with an ultrathin endoscope. As another factor to consider, the experiments in this study were conducted by two ESD experts and although the procedure time was long with the ultrathin endoscope, no significant difference was observed, but the utility of the ultrathin endoscope for trainees should be evaluated. The major limitation of the present study was the small sample size. However, the aim of this study was to evaluate only the feasibility of the ultrathin endoscope for ESD, and large-scale clinical trials are needed in the future.

In this study, the procedure time in the ultrathin group was longer than in the conventional group, but no serious AEs occurred in the ultrathin group.

Conclusion

We conclude that ESD using an ultrathin endoscope seems to be feasible. In the future, we plan to introduce ESD with an ultrathin endoscope at a safe site, and conduct a feasibility study in actual clinical practice.

Footnotes

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hoteya S, Iizuka T, Kikuchi D et al. Benefits of endoscopic submucosal dissection according to size and location of gastric neoplasm, compared with conventional mucosal resection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1102–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Nakayama T et al. Usefulness of oral prednisolone in the treatment of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanaoka N, Ishihara R, Takeuchi Y et al. Intralesional steroid injection to prevent stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal cancer: a controlled prospective study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1007–1011. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Yamada A et al. Polyglycolic acid sheet application to prevent esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2015;47:341–344. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohki T, Yamato M, Ota M et al. Prevention of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection using tissue-engineered cell sheets. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:582–588. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai T, Yanagizawa K, Naito S et al. Evaluation of gastric cancer diagnosis using new ultrathin transnasal endoscopy with narrow-band imaging: preliminary study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:33–36. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki T, Kitagawa Y, Nankinzan R et al. Early gastric cancer diagnostic ability of ultrathin endoscope loaded with laser light source. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1378–1386. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i11.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi K D, Ji F. Prophylactic stenting for esophageal stricture prevention after endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:931–934. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i6.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katada C, Yokoyama T, Yano T et al. Association between macrocytosis and metachronous squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus after endoscopic resection in men with early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus. 2020;17:149–158. doi: 10.1007/s10388-019-00685-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endo H, Inamori M, Murakami T et al. Usefulness of transnasal ultrathin endoscopy for the placement of a postpyloric decompression tube. Digestion. 2007;75:181. doi: 10.1159/000107937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura M, Shibata T, Tahara T et al. Usefulness of transnasal endoscopy where endoscopic submucosal dissection is difficult. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:378–384. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn J Y, Choi K D, Lee J H et al. Is transnasal endoscope-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm useful in training beginners? A prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1158–1165. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2567-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamamura M, Shiroeda H, Tahara T et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of an esophageal tumor using a transnasal endoscope without sedation. Endoscopy. 2014;46 01:E115–E116. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1364885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miura Y, Hayashi Y, Lefor A K et al. The pocket-creation method of ESD for gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:457–458. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi D, Tanaka M, Suzuki Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial pharyngeal carcinoma using transnasal endoscope. VideoGIE. 2021;6:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy. 2010;42:265–271. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]