Summary

Stem cell homeostasis requires nuclear lamina (NL) integrity. In Drosophila germ cells, compromised NL integrity activates the ATR and Chk2 checkpoint kinases, blocking germ cell differentiation and causing germline stem cell (GSC) loss. Checkpoint activation occurs upon loss of either the NL protein emerin or its partner Barrier-to-autointegration factor, two proteins required for nuclear reassembly at the end of mitosis. Here, we examined how mitosis contributes to NL structural defects linked to checkpoint activation. These analyses led to the unexpected discovery that wild type female GSCs utilize a non-canonical mode of mitosis, one that retains a permeable, but intact nuclear envelope and NL. We show that the interphase NL is remodeled during mitosis for insertion of centrosomes that nucleate the mitotic spindle within the confines of the nucleus. We show that depletion or loss of NL components causes mitotic defects, including compromised chromosome segregation associated with altered centrosome positioning and structure. Further, in emerin mutant GSCs, centrosomes remain embedded in the interphase NL. Notably, these embedded centrosomes carry large amounts of pericentriolar material and nucleate astral microtubules, revealing a role for emerin in the regulation of centrosome structure. Epistasis studies demonstrate that defects in centrosome structure are upstream of checkpoint activation, suggesting that these centrosome defects might trigger checkpoint activation and GSC loss. Connections between NL proteins and centrosome function have implications for mechanisms associated with NL dysfunction in other stem cell populations, including NL associated diseases such as laminopathies.

Keywords: nuclear lamina; LEM-domain proteins; Drosophila oogenesis; germline stem cells; Barrier-to-autointegration factor; Checkpoint kinase 2, mitosis; centrosome; emerin; Otefin

eTOC Blurb

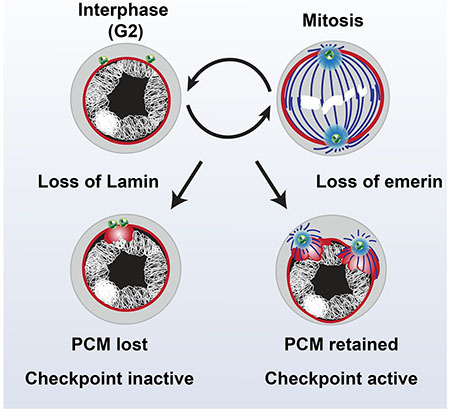

Nuclear lamina (NL) function in stem cell homeostasis is unclear. Duan et al. show that stem cells undergo mitosis with a permeable, but intact NL, which sensitizes them to NL defects. Loss of NL components causes mitotic defects and changes in interphase centrosome structure, alterations linked to a NL checkpoint activation and stem cell loss.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Nuclear structure is shaped by proteins resident in the nuclear lamina (NL). This extensive network is comprised of lamins and hundreds of lamin associated proteins that line the inner nuclear membrane. The NL confers nuclear rigidity and contributes to chromatin organization important for regulation of transcription, replication and DNA repair [1–4]. Additionally, NL proteins transmit regulatory information between cellular compartments through connections that link the nucleoskeleton with the cytoskeleton [5]. Nuclear structure correlates with cell-type specific changes in NL composition [6–9], differences that impact genome organization and function during development [10–12].

The LAP2-emerin-MAN1 domain (LEM-D) protein family has a prominent role in the NL [13, 14]. These proteins share an ~40 amino acid domain (LEM-D) that interacts with Barrier-to-Autointegration Factor (BAF, sometimes referred to as BANF1; [15–18]), a conserved chromatin protein. In non-dividing cells, interactions between LEM-D proteins and BAF link the genome with the nuclear periphery [19–21]. In dividing cells, these interactions control mitotic spindle assembly and positioning, as well as nuclear reassembly at the end of mitosis [22–26]. These properties highlight mechanisms wherein the LEM-D and BAF partnership contributes to nuclear architecture.

Physiological aging and many diseases are associated with changes in nuclear structure [27, 28]. Indeed, misshapen and lobulated nuclei are common features of laminopathies, diseases that result from mutations in genes encoding NL proteins [29]. Laminopathies affect some cell-types more than others, with primary defects found in skeletal muscle, skin, fat, and bone [30, 31]. Age-associated worsening of laminopathic diseases has been linked to failures in stem cell maintenance [32, 33], suggesting that the NL plays an important role in balancing stem cell proliferation with differentiation. Although contributions of the NL to stem cell function are being investigated [12, 34–36], mechanisms that preserve healthy stem cell populations and promote tissue homeostasis remain poorly understood.

Studies in Drosophila melanogaster have identified roles for LEM-D proteins and BAF in adult stem cell maintenance [37, 38]. Drosophila encodes three NL LEM-D proteins that bind BAF, including two emerin orthologues (emerin also known as Otefin and emerin2 also known as Bocksbeutel) and dMAN1 [39]. Notably, loss of emerin compromises homeostasis of adult stem cells in the female and male germlines [37, 38, 40], blocking germ cell differentiation and causing GSC loss. These defects are coupled with GSC-restricted deformation of the NL and accumulation of DNA damage [41], phenotypes that mirror those found in laminopathic cells [42–45]. Strikingly, gametogenesis of Drosophila emerin mutant germ cells is rescued by mutation of two DNA damage response (DDR) kinases, the responder kinase Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) or the transducer kinase Checkpoint kinase 2 [Chk2; [41]]. Although emerin mutant GSCs carry DNA damage, genetic and molecular analyses suggest that ATR and Chk2 activation occurs independently of canonical DNA damage triggers and is linked to the NL structural deformation [41]. Germ cell specific BAF depletion also causes NL deformation and GSC loss that is partially rescued by chk2 mutation [46]. These findings indicate that emerin and BAF contribute to shared NL functions needed for GSC maintenance.

Here, we extend our investigations of events associated with activation of the NL checkpoint. Prompted by shared requirements for emerin and BAF in nuclear reassembly, we examined whether defects in mitosis were responsible for NL deformation and checkpoint activation. To this end, we followed the structure of the NL throughout female GSC (fGSC) mitosis. These analyses led to the unexpected discovery that wild type fGSCs use a non-canonical mode of mitosis, wherein a permeable, but intact, nuclear envelope (NE) and remodeled NL remain throughout mitosis. We demonstrate that this mode of mitosis imposes requirements for NL components, evidenced by observations that depletion or loss of NL components causes defects in centrosome positioning and spindle structure. In emerin mutant fGSCs, centrosomes remain embedded in the interphase NL and retain large amounts of pericentriolar material (PCM) that nucleates astral microtubules. These observations reveal a role for emerin in the regulation of centrosome structure. Epistasis studies demonstrate that PCM retention in emerin mutant GSCs is upstream of Chk2 activation, indicating that the altered structure of the interphase centrosome is linked with NL checkpoint activation. Based on our data, we propose that other stem cells might employ distinct modes of mitosis that sensitize these cells to defects in the NL. These findings have implications for mechanisms associated with NL dysfunction in other systems, including laminopathies.

Results

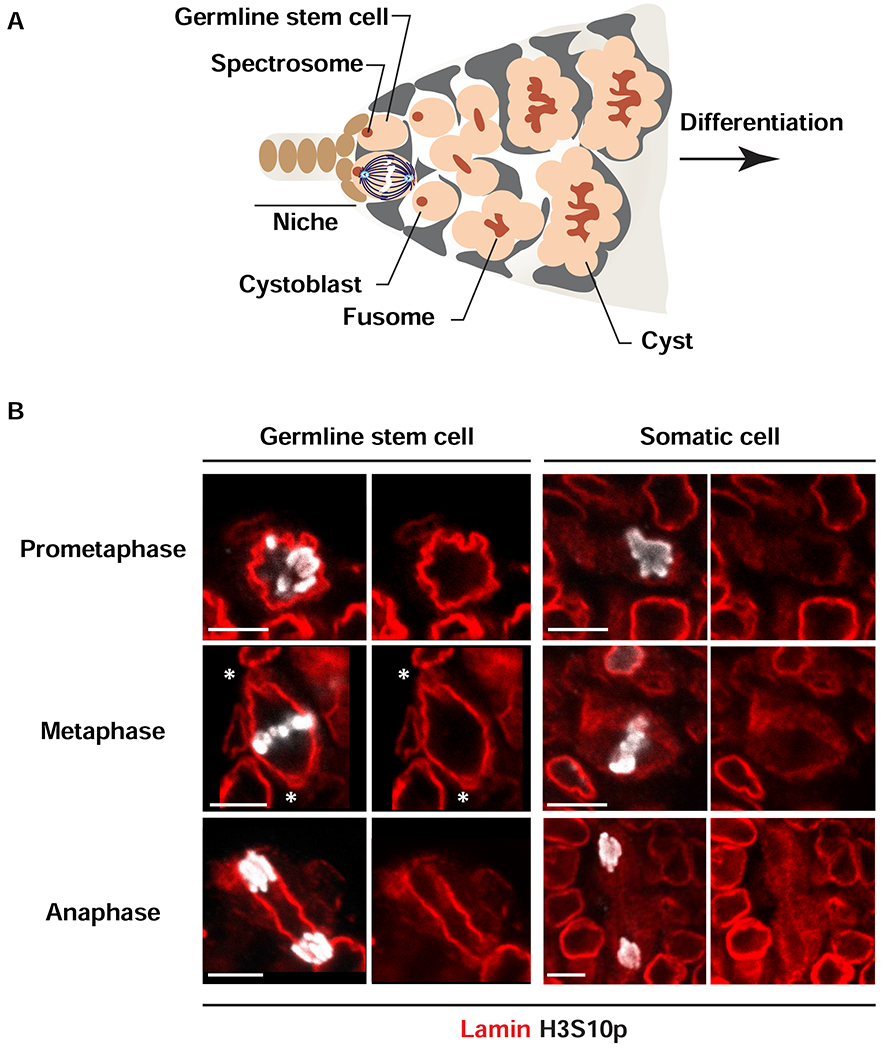

The NL does not disperse during fGSC mitosis.

We predicted that NL defects in emerin and baf mutant fGSCs might result from aberrant nuclear reformation in mitosis. To this end, we investigated fGSC mitosis in wild type and germline mutants that are defective in NL components. Drosophila ovaries are divided into sixteen to twenty ovarioles, each with a stem cell niche carrying two to three GSCs (Figure 1A). Asymmetric mitotic fGSC divisions occur perpendicular to the niche, oriented by interactions between the centrosome and the germ line-specific spectrosome, a cytoskeletal organelle that localizes to the interface between fGSCs and somatic niche cells (Figure 1A; [47, 48]). Oriented divisions produce one self-renewing daughter that remains connected to the niche and one differentiating daughter (cystoblast) that is displaced from the niche. We first studied mitotic divisions of fGSCs in wild type ovaries of newborn females, using their stereotypical location for identification. Ovaries were stained with antibodies against the germline-specific helicase Vasa to identify germ cells, phosphorylated serine 10 of Histone H3 (H3S10p) to identify condensed chromosomes in mitotic cells, and antibodies against the farnesylated B-type Lamin (Lamin-B, also known as Lamin Dm0) to follow the NL structure, as this is the only Lamin expressed in fGSCs [49]. fGSCs divisions are rare, with an average of 2 to 3 mitotic fGSCs among the 50 to 60 fGSCs in each ovary [47]. Even so, all stages of mitosis were identified (Figure 1B). Surprisingly, these analyses uncovered a striking difference from canonical mitosis [50]. In contrast to the expected NL dispersal, we found that a continuous NL surrounds condensed chromosomes from prometaphase to anaphase (Figure 1B). These data demonstrate that in fGSCs, the NL persists throughout mitosis.

Figure 1. Lamin-B does not disperse during mitoses of adult GSCs.

(A) Shown is a schematic of a germarium, the structure that houses the stem cell niche in the adult ovary. Somatic cells of the germarium include cells comprising the niche (brown) and lining the anterior of the germarium (grey). Each niche anchors two or three germline stem cells (GSCs, peach). Asymmetric GSC divisions result from anchoring one pole of the mitotic spindle to the anterior spectrosome (red), located at the niche-stem cell interface. Asymmetric GSC divisions produce one self-renewing daughter that remains at the niche and a second differentiating daughter, cystoblast (peach) that enters into synchronized interconnected mitotic divisions anchored to a branched spectrosome or fusome (branched red structure). (B) Shown are representative nuclear images of wild type GSCs and somatic mitotic cells in adult ovaries stained with antibodies against Vasa (not shown), Lamin-B (red) and H3S10p (white). Stages of mitosis are labeled on the left. Asterisks indicate locations of Lamin-B looped structures (centrosomes). Scale bars: 5 μm. Numbers of nuclei analyzed are summarized in the Table S1.

Ovaries also contain somatic cells undergoing mitosis. To understand NL dynamics in somatic cell mitosis, we identified cells that were H3S10p positive, but Vasa negative. In contrast to fGSCs, the NL in mitotic somatic cells became fuzzy and lacked definition in prometaphase (Figure 1B) and remained dispersed during metaphase and anaphase. These analyses reveal that structural rearrangements of the NL in mitosis differ between cell types.

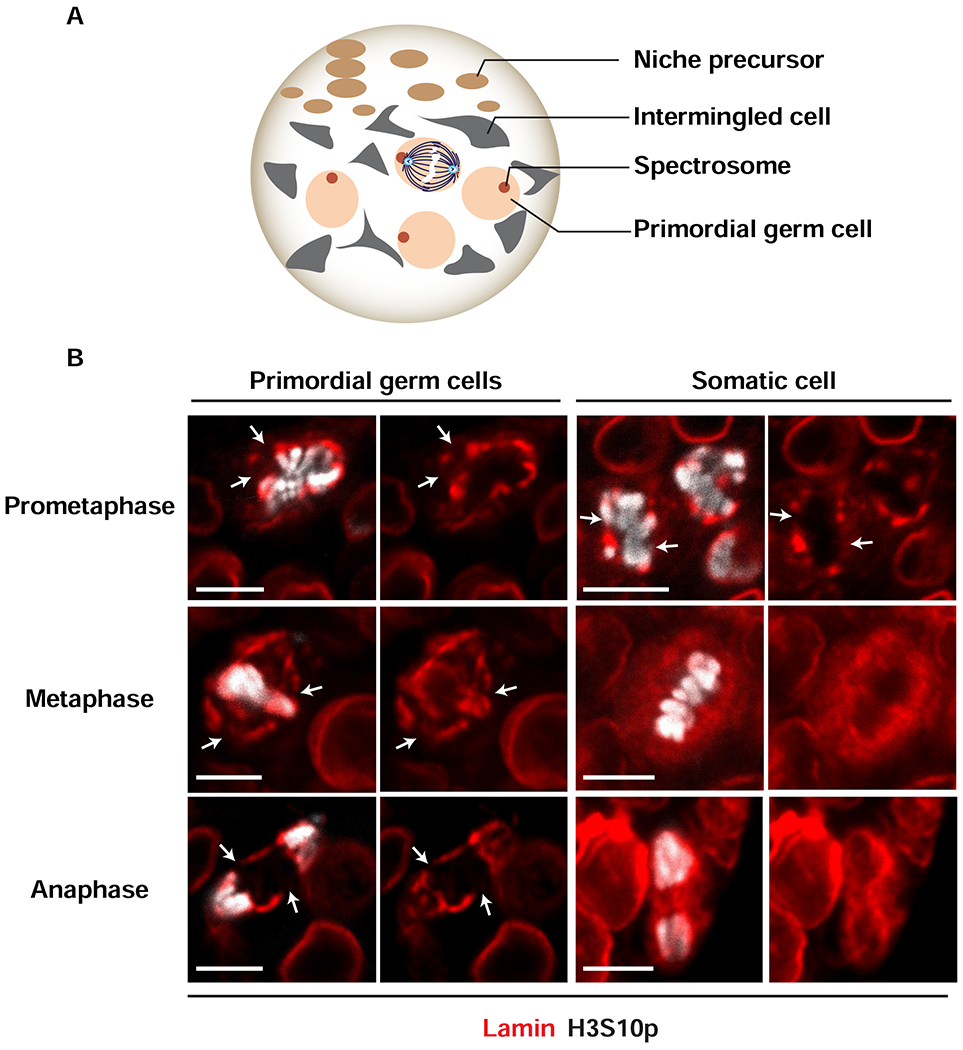

Germ cell mitosis undergoes a developmental switch

To understand whether NL retention is a general feature of germ cells mitosis, we studied mitosis of primordial germ cells (PGCs) in the larval ovary. During early larval development, PGCs divide symmetrically every 24 hours to produce sufficient numbers of stem cells to fill developing stem cell niches [51]. These symmetric mitotic divisions are randomly oriented, with each division producing two daughter PGCs (Figure 2A; [52]). Mid-third instar ovaries were stained with antibodies against Vasa (not shown), H3S10p and Lamin-B. Again, all stages of mitosis were identified (Figure 2B). In PGCs, we found that the NL was discontinuous in prometaphase, with Lamin-B patches enriched near condensing chromosomes. The NL remained patchy throughout metaphase and anaphase, with NL breaks evident at the poles (Figure 2B). These data indicate that mitotic NL dynamics differ between PGCs and fGSCs and imply that the change from symmetric to asymmetric division correlates with a switch in NL retention during mitosis.

Figure 2. Cell-type specific structural changes in NL in mitotic cells in larval ovaries.

(A) Shown is a schematic of a mid-third instar larval ovary. At this stage, the ovary carries ~100 primordial germ cells (PGCs, peach) that are identified by a spherical spectrosome (red) and multiple types of somatic cells, including anterior niche precursor cells (brown) and intermingled cells (grey). Expansion of PGC numbers occurs by random orientation of symmetric mitotic divisions (center) that produce two daughter PGCs. (B) Shown are representative nuclear images from wild type PGCs and somatic cells that are undergoing mitosis in the mid-third instar larval ovary. Ovaries were stained with antibodies against Vasa to identify germ cells (not shown), Lamin-B (red) to identify the NL and H3S10p (white) to identify cells in mitosis (stages of mitosis are labeled on the left).White arrow indicate locations of breaks in the NL. Scale bars: 5 μm. Numbers of nuclei analyzed are summarized in Table S1.

Mitotic somatic cells were also identified in larval ovaries (Figure 2B). In these cells, the mitotic NL was discontinuous in prometaphase, with patches of NL retained around condensing chromosomes. By metaphase, however, an organized NL was largely gone and Lamin-B staining appeared fuzzy and distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 2B). These analyses emphasize that mitotic structural rearrangements of the NL are cell-type specific.

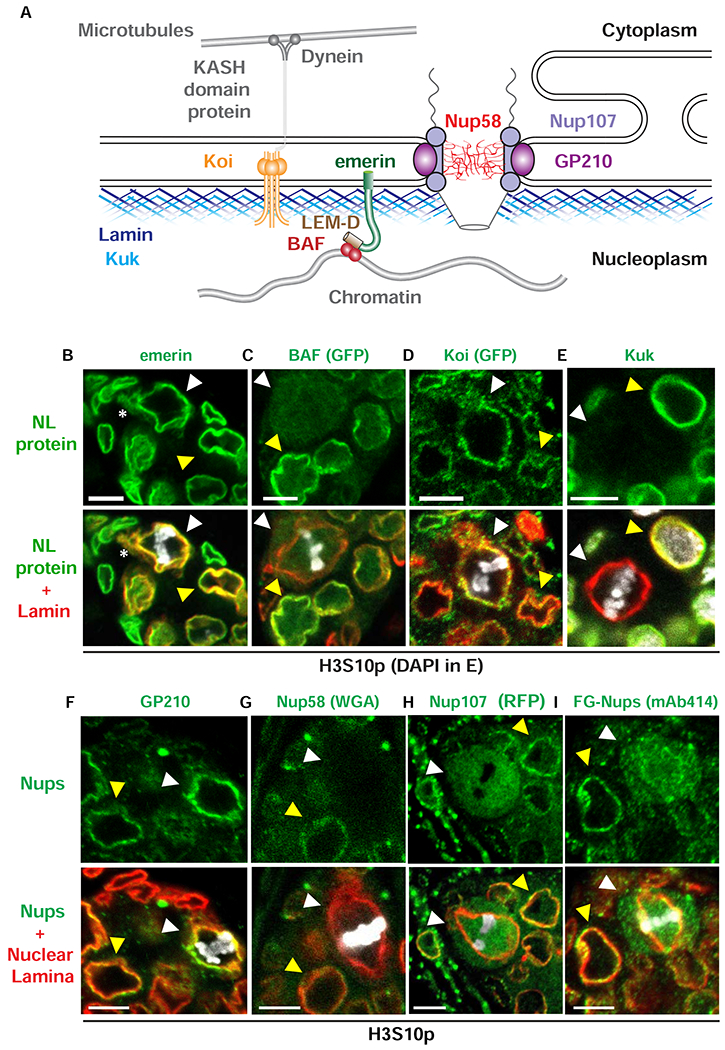

The mitotic and interphase NL differ

The interphase fGSC NL is an extensive protein network scaffolded by the B-type Lamin (Figure 3A; [49]). We wondered whether the composition of the interphase NL is altered in mitosis. To this end, we defined the location of multiple NL proteins, co-staining ovaries with antibodies against H3S10p, Lamin-B and several NL proteins. First, we examined emerin, the only NL LEM-D protein essential for fGSC homeostasis [37–39, 53]. We found that emerin remained in a network throughout mitosis, co-localizing with Lamin-B (white arrowhead, Figure 3B; S1A). Second, we examined BAF, an emerin partner protein. Although emerin remains in the mitotic NL, BAF does not (white arrowhead, Figure 3C). Indeed, BAF disperses beginning in prometaphase (Figure S1B), a timing that is consistent with previous demonstrations that BAF phosphorylation releases BAF from chromatin in mitosis [54, 55]. BAF release correlates with a loss of NL ruffling, indicating that BAF contributes to tethering of fGSC chromosomes to the NL. Third, we examined Klaroid (Koi), a core component of the Linker of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) complex [56]. Proteins in this complex couple the nuclear interior to the cytoskeleton for transduction of mechanical signals across the nuclear membrane [57]. Koi is an ovary-expressed inner nuclear membrane SUN domain protein that connects to the outer nuclear membrane KASH domain protein, Klarsicht. We detected Koi staining in the mitotic NL (white arrowhead, Figure 3D). Fourth, we investigated the localization of Kugelkern (Kuk), a farnesylated inner NE protein. Strikingly, Kuk staining of the NL is lost in metaphase fGSCs (white arrowhead, Figure 3E). Several explanations might account for the Kuk disappearance, including loss of the NE that anchors Kuk, removal and turnover of Kuk itself or structural changes in the NL that mask the Kuk antibody epitope. Regardless, these data demonstrate that NL structure undergoes cell-cycle dependent changes.

Figure 3. The mitotic NL differs in composition from the interphase NL.

(A) Shown is a schematic of proteins found in interphase NE and NL. Outer and inner nuclear membranes are fused at nuclear pores, where NPCs are located. NPCs are anchored to the NE by a transmembrane ring complex that includes GP210 (purple). This complex is connected to the Nup107 complex (light purple) that forms the core scaffold of the NPC and associates with the central FG-repeat Nups that include Nup58 (red). The NL lies underneath the inner nuclear membrane. The NL contains two farnesylated proteins, Lamin-B (dark blue) and Kugelkern (Kuk, light blue). Other NL proteins include the LEM-D protein emerin (green) that interacts with BAF (red) and the SUN domain protein Klaroid (Koi, orange) that interacts with KASH domain proteins (grey) to form the LINC complex that connects to the cytoskeleton through motor proteins, such as dynein (grey). (B-E) Confocal images of wild type metaphase fGSC nuclei in ovaries of newly born females that were stained with antibodies against several NL proteins (green, top) and co-stained with Lamin-B (red, bottom) and H3S10p (B-D, white) or DAPI (E, white). White arrowheads point to metaphase fGSCs. Yellow arrowheads point to interphase cells. Asterisks indicate locations of the Lamin-B loop structures (centrosome). Scale bar: 5 μm. (F-I) Confocal images of wild type metaphase fGSC nuclei in ovaries of newly born females that were stained with antibodies against several NPC components (green, top), NL proteins (red, merge bottom) and H3S10p (white). The NL protein corresponds to emerin in the co-stain with GP210 (F) or Lamin-B in the co-stain with the other Nups (G-I). In Drosophila, Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) staining primarily reflects the localization of one FG-Nup, Nup 58 [100]. White arrowheads point to metaphase fGSCs. Yellow arrowheads point to interphase cells. Scale bar: 5 μm. Numbers of nuclei examined for each staining are summarized in Table S1. See also Figures S1 and S2.

The absence of detectable Kuk raised the question of whether the NE remained during mitosis. To this end, we defined the localization of GP210, a transmembrane nucleoporin that anchors the nuclear pore complex (NPC) to the nuclear membrane. We found that GP210 remains colocalized with Lamin-B in the mitotic NL (white arrowhead; Figure 3F), implying that the NE remains intact during fGSC mitosis. In some organisms, even though the NE remains in mitosis, NPCs are partially disassembled, allowing for the exchange of proteins, such as tubulin, between the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments [58]. To determine whether NPCs are remodeled, we compared the location of additional nucleoporins (Nups) in interphase and mitotic GSCs. Antibody staining assessed the distribution of Nups that comprise the central channel (Nup58 and the FG-repeat Nups; Figure 3G, I) and the Y complex Nup107 (Figure 3H; [59]). In all cases, we found that these Nups distributed through the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments in mitotic fGSCs (white arrowheads; Figure 3G–I). These data indicate that NPC structure changes during fGSC mitosis.

Based on the structure of mitotic NPCs, we wondered whether the nuclear barrier function remains. To address this question, we examined the mitotic localization of Vasa, Sex lethal (Sxl) and Mei-P26, three cytoplasmic RNA binding proteins. We found that all proteins are redistributed, localizing to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure S2 A–C). To complement these observations, we examined the mitotic localization of Topoisomerase 2 (Top2), Stand still (Stil) and Heterochromatin Protein 1a (HP1a), three nuclear chromatin binding proteins. Whereas Top2 and HP1a remained enriched in the nuclear compartment (Figure S2 D, F), Stil was evenly distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Figure S2 E). These findings, coupled with observations of the changes in the mitotic NPC (Figure 3 F–I), suggest that fGSCs employ an intermediate form of mitosis, one that is not completely closed because the NE becomes permeable, nor completely open because the NE and NL remain intact.

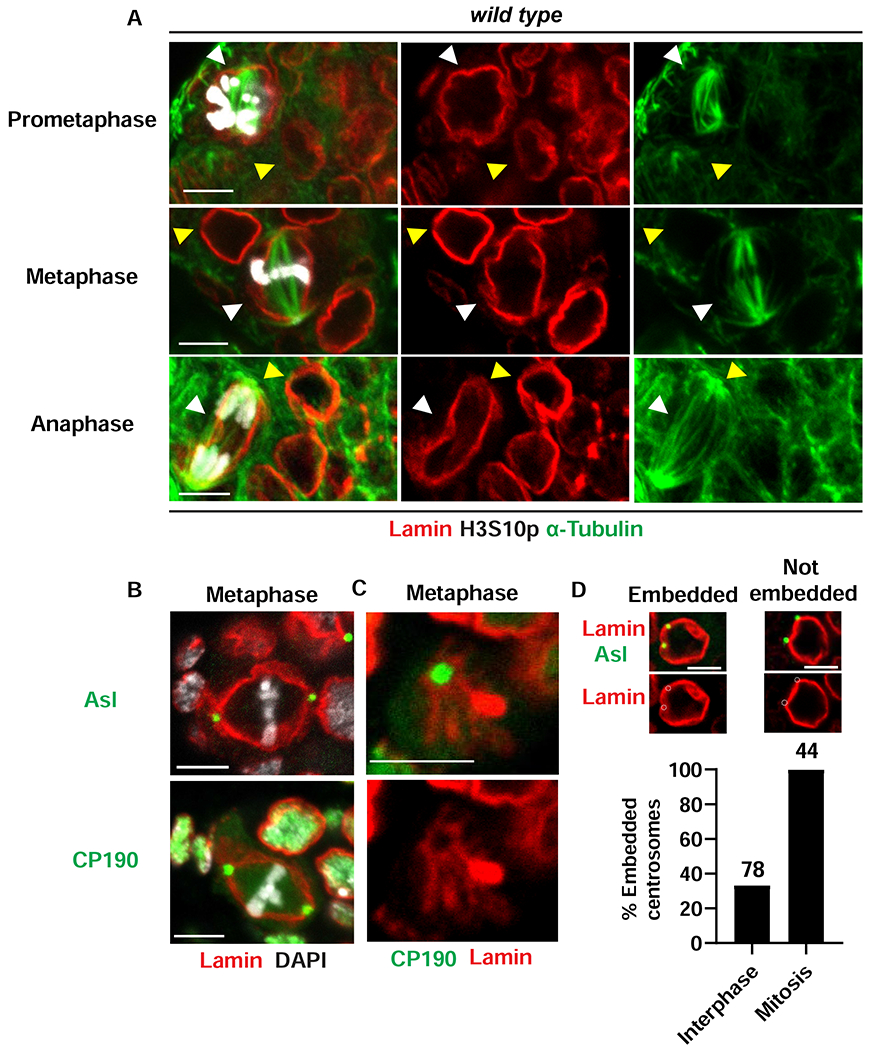

Spindle microtubules and centrosomes are enveloped by the mitotic NL

Permeability of the mitotic NPC suggested that tubulin monomers might access the nuclear compartment to form the mitotic spindle within the NL boundary. To test this prediction, ovaries from newly born females were stained with antibodies against α-Tubulin, Lamin-B and H3S10p. These studies demonstrated that spindle microtubules are enveloped by the NL throughout fGSC mitosis (Figure 4A). Nucleation and organization of spindle microtubules depend upon centrosomes. In the Drosophila syncytial embryo, centrosomes localize outside of the retained NL, such that NL breakdown at the poles must occur to allow access of spindle microtubules to chromosomes for segregation [60, 61]. Our studies, however, suggested that Lamin-B remained at the poles, forming looped structures (asterisk Figures 1B, 3B). Based on these observations, we reasoned that centrosomes were likely inserted into the NL during mitosis. To test this possibility, we co-stained ovaries with antibodies against Lamin-B, H3S10p and two centrosomal proteins, Asterless (Asl) that demarcates the centriole and Centrosomal Protein of 190 kD (CP190) that demarcates the pericentriolar material (PCM). We found that both proteins localize within the mitotic NL (Figure 4B). In several images, the angle revealed that centrosomes were inserted into a Lamin-B-reinforced cup-like structure (Figure 4C). Super-resolution microscopy revealed that emerin also forms a cup-like structure that holds the centrosome (Figure S2G). We conclude that mitotic centrosomes are embedded within the mitotic NL.

Figure 4. The mitotic spindle is nucleated from centrosomes embedded within the NL.

(A) Shown are confocal images of wild type GSC nuclei in ovaries that were stained with antibodies against α-Tubulin (Green) Lamin-B (red) and H3S10p (white). Mitotic stages are labeled on the left. White arrowheads point to metaphase fGSCs. Yellow arrowheads point to interphase cells. Scale bars: 5 μm. (B) Confocal images of wild type metaphase fGSC nuclei in ovaries that were co-stained with antibodies against centrosome components, Asl and CP190 (green), Lamin-B (red) and DAPI (white). Scale bars: 5 μm. (C) Shown is a confocal image focused on the centrosome region in a wild type fGSC mitotic nucleus in an ovary that was stained with antibodies against CP190 (green) and Lamin-B (red). Scale bars: 5 μm. (D) Top: Shown are confocal images of wild type interphase fGSCs stained with antibodies against Asl (green) and Lamin-B (red). Examples of fGSCs with embedded or not embedded centrosomes are shown. Embedding is defined by a greater than 50% overlap between the centrosome and the NL. Bottom: Bar graph showing the percentage of embedded centrosomes in wild type GSCs. Stages of the cell cycle are listed at the bottom and the number of GSCs scored is listed at the top. Numbers of nuclei examined for each staining in (A)-(C) are summarized in Table S1. See also Figure S2.

In interphase cells, centrosomes are cytoplasmic organelles that closely associate with the nucleus [62]. Our observation that the mitotic centrosomes are embedded in the NL raised the question of the location of centrosomes in interphase fGSCs. To this end, we examined ASL localization in the H3S10p-negative GSCs (Figure 4D). Quantification of the overlap of ASL with Lamin-B demonstrated that few centrosomes (36%, n=78) are embedded in the NL (Figure 4D). We conclude that centrosomes are largely adjacent to nuclei in interphase and become embedded in a remodeled NL at the beginning of mitosis.

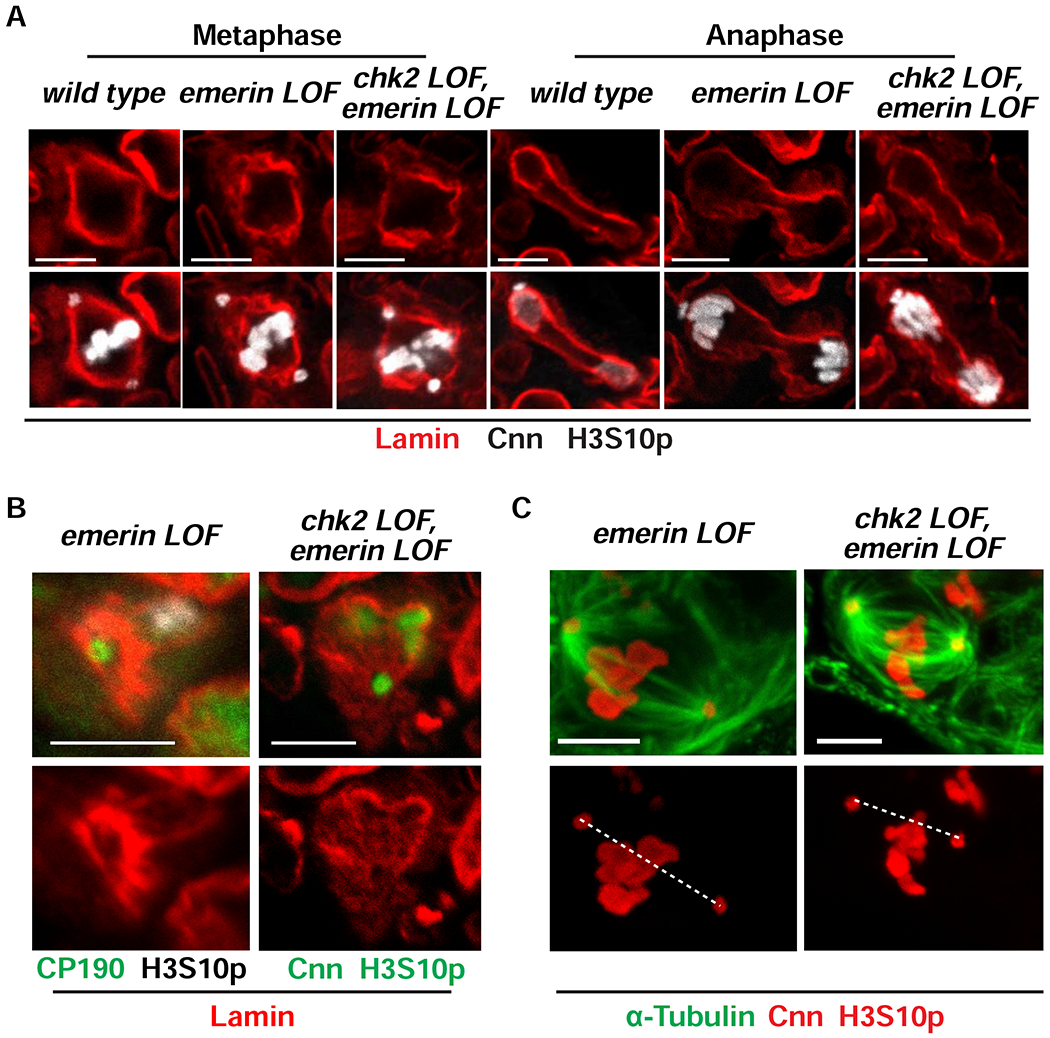

Emerin contributes to mitotic spindle structure and chromosome segregation

We investigated whether retention of a mitotic NL is essential for GSC homeostasis. To this end, we examined mitosis in emerin mutant ovaries. These ovaries were co-stained with antibodies against the PCM marker Centrosomin (Cnn) and H3S10p to detect mitotic fGSCs, and antibodies against either Lamin-B to examine the mitotic NL or α-tubulin to examine mitotic spindles. Several observations were made. First, loss of emerin distorted the mitotic NL, resulting in an irregular Lamin-B network in metaphase and anaphase cells (Figure 5A). Second, without emerin, the Lamin-B-reinforced centrosome cup-like structure thickened and collapsed relative to structures found in wild type fGSCs (compare Figure 4C with 5B). Third, mitotic spindles in emerin mutant fGSCs became long, wispy and bent (Figure 5C), contrasting with the organized bipolar arrays found in wild type fGSCs (Figure 4A). Fourth, centrosomes were separated by increased distances relative to wild type in mitotic fGSCs (Figure S3A) and were mis-aligned with metaphase chromosomes (median positioning ratio of 0.69 relative to 0.85 for wild type; Figure S3B). Fifth, the frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase increased relative to wild type reference controls (25%, n=16 relative to 11%, n=37 for wild type; Figure S3B). Together, these data imply that loss of emerin alters the structure of the mitotic NL and mitotic spindles, which together interfere with chromosome segregation.

Figure 5. Loss of emerin disrupts mitotic NL structure and spindle formation.

(A) Representative confocal images of metaphase and anaphase fGSC nuclei from ovaries of the indicated genotype that were stained with antibodies against Lamin-B (red), H3S10p (white) and Cnn (white). (B) Shown are confocal images of mitotic nuclei focusing on centrosome regions in emerin and chk2, emerin mutant fGSCs in ovaries that were stained with antibodies against centrosomal proteins CP190 or Cnn (green), H3S10p (white on the left and green on the right) and Lamin-B (red). Scale bars: 5 μm. (C) Representative images of metaphase fGSC nuclei in emerin and chk2, emerin mutant ovaries that were stained with antibodies against α-Tubulin (green), Cnn (red) and H3S10p (red). The dashed line connects the centers of two centrosomes. Quantification of centrosome positioning can be found in Figure S3B. Scale bar: 5 μm. Numbers of nuclei examined for each staining are summarized in Table S1. See also Figures S3 and S4.

Mitotic defects might result from direct effects of emerin loss or indirect effects from ATR/Chk2 checkpoint activation. To distinguish between these possibilities, chk2, emerin double mutant ovaries were co-stained with antibodies against Cnn and H3S10p, and either Lamin-B or α-tubulin. Several mutant phenotypes remained in the chk2, emerin double mutants, including irregularities of the mitotic NL, distortion of mitotic spindles and an increased frequency of lagging anaphase chromosomes (Figures 5 A,C; S3 B,C). Other phenotypes resolved, including thickening of the Lamin-B-reinforced centrosome cup and distances between centrosomes in mitosis (Figures 5B, S3A). These observations demonstrate that Chk2 activation contributes to some, but not all, mitotic defects observed in emerin mutant fGSCs.

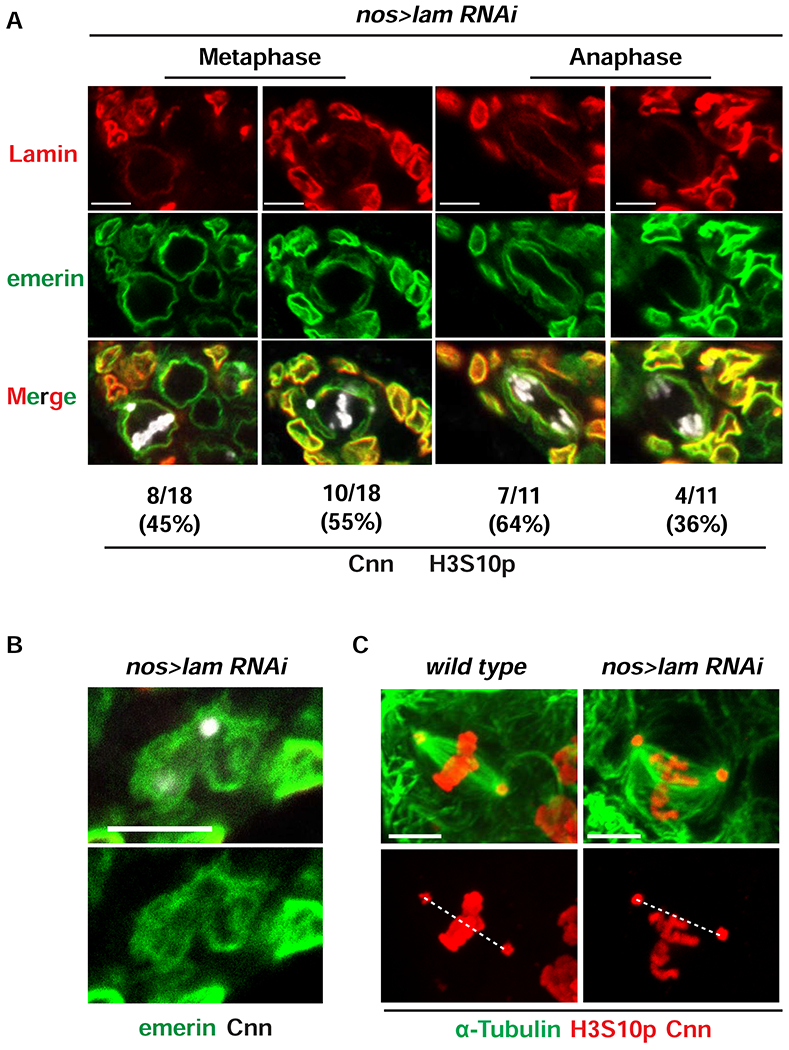

Lamin-B depletion affects mitosis without fGSC loss

We extended our studies to test the requirement for Lamin-B in fGSC mitosis. To this end, we depleted Lamin-B using the germline specific nanos (nos)-gal4vp16 driver to activate transcription of a UASp responder transgene encoding a lamin hairpin RNA (lam RNAi). Surprisingly, ovaries dissected from the nos>lam RNAi females contained developing oocytes and females laid eggs, raising the question of whether Lamin-B levels were reduced. To this end, we stained nos>lam RNAi ovaries with Lamin-B antibodies and found a strong reduction of protein levels, evident from comparison between germ cells and somatic cells (Figure S4A). Even so, Lamin-B was not eliminated and remained as nuclear aggregates in most (67%, n=36) interphase GSCs (Figure S4B). Attempts to increase RNAi efficiency did not improve Lamin-B depletion (Figure S4A), consistent with observations that B-type lamins are long-lived proteins [63].

We examined effects of Lamin-B depletion on interphase NL structure. We stained nos>lam RNAi ovaries with antibodies against emerin and Kuk and found that emerin and Kuk distributed throughout the nuclear periphery and were enriched in remaining Lamin-B aggregates (Figure S4B). These observations suggest that a NL-like network assembles in the presence of low levels of Lamin-B and this NL is capable of supporting fGSC homeostasis. Although surprising, proliferation and differentiation of stem cells lacking all Lamin isoforms has been previously reported [64].

Next, we defined how Lamin-B depletion affected fGSC mitosis. Several observations were made. First, interphase Lamin-B aggregates disappeared upon entering mitosis (Figure S4C) and were replaced by a low level distribution of Lamin-B in the mitotic NL (Figure 6A). In some fGSCs (45%), this redistribution appeared complete and these fGSCs had an even distribution of emerin. In other fGSCs (55%), the redistribution of Lamin-B was patchy, and the distribution of emerin matched that of Lamin-B (Figure 6A). These findings suggest that the Lamin-B is required for maintenance of emerin in the mitotic NL. Second, Lamin-B depletion affected the NL network surrounding the centrosome, evidenced by the poorly structured and diffuse distribution of emerin (Figure 6B). Third, the bipolar array of microtubules in metaphase nos>lam RNAi fGSCs was bent, disorganized, and offset from the aligned chromosomes (median positioning ratio of 0.34 relative to 0.85 for wild type; Figures 6C, S3B). In this genetic background, the altered spindle alignment was linked to a shortened distance between centrosomes (Figure S3A). Fourth, Lamin-B depletion increased the frequency of lagging anaphase chromosomes (56%, n=18; Figure S3C). Collectively, these data indicate that Lamin-B is required for the integrity and function of mitotic spindles in fGSCs.

Figure 6. Lamin-B is required for fGSC mitosis.

(A) Representative confocal images of metaphase and anaphase fGSC nuclei found in nos>lam RNAi ovaries that were stained with antibodies against Lamin-B (red), emerin (green), H3S10p (white) and Cnn (white). The number and percentage of nuclei found in each category are denoted below each image. (B) Shown is a confocal image of a mitotic nos>lam RNAi nucleus, focused on the centrosome region from ovaries stained with antibodies against emerin (green) and Cnn (white). Scale bars: 5 μm. (C) Representative images of metaphase fGSC nuclei isolated from wild type and nos>lamin RNAi ovaries that were stained with antibodies against α-Tubulin (green), Cnn (red) and H3S10p (red). The dashed line connects the centers of the centrosomes. Quantification of centrosome positioning can be found in Figure S3A. Scale bar: 5 μm. Numbers of nuclei examined for each staining are summarized in Table S1. See also Figure S3.

Activation of the NL checkpoint is linked to changes in centrosome structure

fGSCs display mitotic defects upon loss of emerin or Lamin-B (Figures 5, 6). Even so, only emerin mutant females carry small ovaries that show defects in germ cell differentiation and fGSC survival. In contrast, oogenesis in nos>lam RNAi females proceeds without Chk2 activation, as fGSCs survive and females lay eggs without fused dorsal appendages, a hallmark of Chk2 activation [65]. However, eggs laid by nos>lam RNAi females might carry defects, as fewer nos>lam RNAi eggs hatch than wild type control eggs (Figure S4D), a defect that might result from limited levels of Lamin-B available for early nuclear divisions in the embryos or aberrant oogenesis. Together, these data indicate that emerin loss and Lamin-B depletion have distinct impacts on the NL checkpoint in fGSCs.

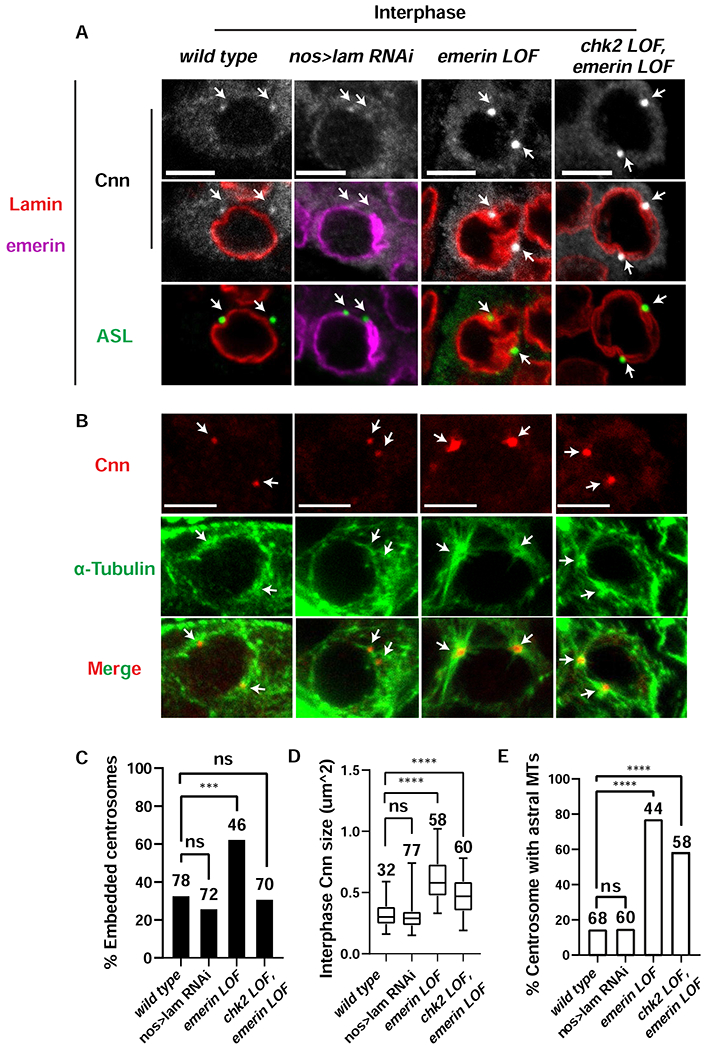

Insights into a possible mechanism for differences in checkpoint activation came from analysis of the NL and centrosomes in interphase emerin and nos>lam RNAi mutant fGSCs (Figure 7). First, in nos>lam RNAi fGSCs, the NL was regular and smooth, with the exception of thickening at positions of remaining Lamin-B aggregate (Figures 7A, S4B). In contrast, in emerin mutants, NL thickening and irregularity was widespread (Figure 7A). Second, the location and structure of the interphase centrosome differed. In nos>lam RNAi fGSCs, few (33%) centrosomes were NL embedded, whereas in emerin mutants, most (63%) were NL embedded, with embedded centrosomes positioned at areas of NL thickening (Figure 7A,C). Third, centrosomes in interphase nos>lam RNAi fGSCs carried Cnn levels similar to wild type fGSCs, whereas emerin mutant fGSC centrosomes had significantly higher levels (Figure 7 A,D), uncovering structural defects in the interphase centrosomes. To understand the extent of these defects, we examined interphase fGSCs stained with antibodies against two additional PCM proteins, γ-tubulin and CP190. We found that only emerin mutant fGSCs showed elevated levels of γ-tubulin (Figure S5 A,B), whereas CP190 was not retained in centrosomes and returned to the nucleus (Figure S5C). We also defined levels of Asl in interphase fGSCs, as PCM recruitment of Cnn depends upon centriolar Asl [66]. Notably, Asl levels in emerin mutant GSCs were similar to wild type (Figure S5C,D). Fourth, the fGSCs microtubule network in nos>lam RNAi and emerin mutant fGSCs differed. Notably, the microtubule network was dramatically reorganized in emerin mutant fGSCs, with most (78%) interphase centrosomes nucleating astral microtubules (Figure 7B, E). These observations align with the increased PCM levels in emerin mutants. Taken together, our findings indicate that emerin contributes to regulation of centrosome structure, with its loss leading to defects in interphase levels of PCM.

Figure 7. PCM retention in emerin mutants correlates with checkpoint activation.

(A) Confocal images of interphase fGSC nuclei in ovaries that were stained with antibodies against Lamin-B (red), emerin (purple), the centriolar marker Asterless (Asl; green) and the PCM marker Cnn (white). Genotypes are indicated along the top. Scale bars represent 5 μm. Arrows point to the location of centrosomes. (B) Confocal images of interphase fGSCs in ovaries that were stained with antibodies against H3S10p (not shown), Cnn (red) and α-Tubulin (green). Genotypes are the same as in (A). Scale bars represent 5 μm. Arrows point to the location of centrosomes. (C) Shown is a bar graph comparing the percentage of NL embedded centrosomes in interphase fGSCs of the indicated genotype. Embedded centrosomes were defined as centrosomes that showed at least 50% overlap with the NL staining. The number of centrosomes assessed is noted above each bar. Asterisks indicate significance [Two proportion Z-test (ns: not significant, *** < 0.001)]. (D) Shown are box plots of the size of centrosomal Cnn in interphase fGSCs of the indicated genotype. For each box plot, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentile interval, the line represents the median and the whiskers represent the 5th to 95th percentile interval and non-outlier range. The number of centrosomes analyzed is noted above each box. Asterisks indicate significance [Mann-Whitney U-test, **** <0.0001, ns: not significant]. (E) Shown is a bar graph comparing the percentage of interphase centrosomes that nucleate aster microtubules (MT). The number of centrosomes quantified is noted above each bar. Asterisks indicate significance using the two proportion Z-test (ns: not significant; ****<0.0001). See also Figure S5 and Table S1.

Differences between centrosome structure in nos>lam RNAi and emerin mutant fGSCs suggested that structural changes in the centrosome might lead to activation of the NL checkpoint. To test this possibility, we examined the structure of chk2, emerin double mutant interphase fGSC centrosomes. Although most (69%) centrosomes were not embedded in the NL in these mutants (Figure 7C), we observed NL thickening adjacent to the nuclear-associated centrosomes (Figure 7A), suggesting that retention of centrosomes in the NL is not the only cause of NL deformities. Notably, chk2, emerin double mutant centrosomes retained significant amounts of both Cnn and γ-tubulin (Figures 7A,D; S5A,B). Further, most (60%) chk2, emerin double mutant centrosomes nucleated astral microtubules in interphase (Figure 7B, E). These data demonstrate that structural changes in centrosomes are upstream of checkpoint activation. Based on these findings, we propose that changes in centrosome structure activate the NL checkpoint, leading to loss of fGSC homeostasis in emerin mutants.

Discussion

fGSCs use a non-canonical mode of mitosis

The NL has a central role in establishing structures important for the homeostasis of diverse stem cells [67–72]. Indeed, survival of Drosophila GSCs depends upon the integrity of the NL [37, 38], wherein NL deformation is linked to activation of the ATR and Chk2 kinases that leads to GSC loss [41, 46]. Here, we investigated mechanisms leading to NL deformation in fGSCs, examining the role of mitosis in shaping the NL.

Two main modes of mitosis exist, open and closed [58, 73]. In open mitosis, the NE and NL breakdown, enabling spindle microtubules nucleated from cytoplasmic centrosomes to capture and segregate chromosomes. In closed mitosis, mitotic spindles are nucleated by spindle pole bodies (centrosome equivalents) that are embedded in a retained NE. It is generally assumed that metazoan cells use open mitosis, whereas fungi use closed mitosis. This assumption is linked with metazoan-limited expression of Lamin and BAF, two proteins that are required for nuclear reassembly at the end of open mitosis [21, 74]. However, several exceptions to this rule exist, indicating that open and closed mitoses represent extremes of a continuum of mitotic strategies [58, 73]. A classic example of an exceptional mode of mitosis occurs in the Drosophila early embryo. In these early divisions, limited nuclear breakdown occurs, wherein local NE and NL breakdown occurs near centrosomes, with large portions of the NE and NL remaining until metaphase [61]. This NL has a stabilizing function on spindle microtubules, as disruption of the Lamin-B delays prometaphase spindle assembly [75]. However, progression to anaphase requires NL and NE dispersal, as increased stabilization of the Lamin-B prevents spindle elongation [75]. These mitotic events indicate that the regulation of NE and NL remodeling optimizes progression through mitosis.

Mitotic divisions of Drosophila female germ cells also deviate from open mitosis. In contrast to somatic cells in the ovary that show universal NL dispersal (Figures 1B, 2B), germ cells change the mode of mitosis depending on developmental stage. In larval PCGs, nuclear breakdown begins in prometaphase, forming large, broken patches of NL (Figure 2B), whereas in adult fGSCs, the NL remains intact, even into anaphase (Figure 1B). As a result, spindle microtubules form within the mitotic fGSC nucleus, emanating from centrosomes embedded in the NL (Figure 4). Notably, features of this non-canonical mitosis are shared with fungi. For example, in Aspergillus nidulans, the Never-in-mitosis kinase partially disassembles NPCs, increasing permeability of an otherwise intact mitotic NE to allow mitotic regulators access to the prophase nucleoplasm [58]. Similarly, we find that NPCs in mitotic fGSCs are partially disassembled, allowing for exchange of nuclear and cytoplasmic components (Figure 3; S2A–F). However, other features differ between fGCS and fungal mitosis. For example, Saccharomyces cerevisiae carry a centriole-less spindle pole body that is embedded in the NE, which allows nucleation of spindle and astral microtubules within the nuclear compartment [58]. In contrast, the centriole containing centrosomes of fGCSs move into the NE and NL to promote spindle microtubule assembly within the nucleoplasm. fGCS centrosomes are inserted into a cup-like structure comprised of Lamin-B and emerin (Figure 4; S2G), suggesting that localized remodeling of the NE and NL occurs. Based on these comparisons with fungi, we propose that fGSCs employ an intermediate form of mitosis, one that is not completely closed because the NE becomes permeable, nor completely open because the NE and NL remain intact. Our data add additional evidence that metazoans do not solely employ an open mode of mitosis. Indeed, in Drosophila, modes of mitosis are cell-type and developmental-stage specific.

Our genetic studies suggest that NL proteins are required for execution of fGSC mitosis. Loss of emerin or depletion of Lamin-B alters the structure and positioning of mitotic spindles. Both NL mutants increase the frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase (Figure S3C), suggesting that the quality of fGSC mitosis is compromised upon NL dysfunction. Defects in the mitotic spindle might result from disruption of mitotic spindle assembly or mitotic matrix formation, as mammalian Lamin B is a structural component of the spindle matrix that promotes microtubule organization in mitosis [76]. Alternatively, mitotic spindle defects might result from an altered distribution of nuclear pores, as centrosome separation in mitotic prophase is linked to nuclear pore distribution [77]. Further studies are needed to address these possibilities.

The significance of the developmental switch between PGCs and fGSCs mitosis is unclear. Notably, this switch correlates with the transition from symmetric to asymmetric division, suggesting that retention of a mitotic NL might contribute to acquisition of distinct cell fates that occur within a single cell division. Indeed, fGSC homeostasis is linked to the asymmetric inheritance of two nuclear factors that regulate rRNA transcription and maturation, Wicked/U3 snoRNA-associated protein 18 and Underdeveloped/TAF1 [78, 79]. Our data indicate that asymmetric trafficking of these proteins occurs within an intact mitotic NL (Figure 4A), which might help establish the distinct distribution of these proteins and possibly others. For example, microtubules direct the asymmetric distribution of pSmad to one centrosome for its degradation in cultured human embryonic stem cells [80]. Although niche signaling has a dominant role in fGSC maintenance [48], we suggest that retention of a mitotic NL might amplify mechanisms used in asymmetric division.

Structural centrosome changes are linked to NL checkpoint activation.

Although emerin and Lamin-B are required for fGSC mitosis, only loss of emerin leads to fGSC death. Indeed, oogenesis in nos>lam RNAi females occurs without evidence of Chk2 activation. Although the low levels of Lamin-B that remain in nos>lam RNAi fGSCs might be sufficient to guide mitosis, it is also possible that emerin and Lamin-B make distinct contributions. Observations that the structure of the interphase centrosome differs in the two mutant backgrounds provide support for the latter possibility. In emerin mutant fGSCs, centrosomes remain embedded in the NL and these centrosomes retain increased amounts of PCM, defects not observed in nos>RNAi mutants (Figure 7A, C). Embedded centrosomes might contribute to the extensive structural deformation of the NL found in these emerin mutant fGSCs, because the expanded PCM retains γ-tubulin (Figure S5A), the major microtubule nucleating component of the PCM [81]. As a result, emerin but not nos>lam RNAi mutants nucleate astral microtubules in interphase fGSCs (Figure 7B). Epistasis studies demonstrate that both PCM expansion and microtubule nucleation remain in chk2, emerin double mutants (Figure 7A), implying that these features are independent or upstream of checkpoint activation. We predict that differences in interphase centrosome structure are connected to NL checkpoint activation.

Mechanisms responsible for expanded PCM in emerin mutants are unknown. Centrosome maturation and disassembly involve regulated activities of kinases that promote PCM expansion and phosphatases that reverse phosphorylation of PCM proteins [81–83]. Structural defects of the interphase emerin mutant centrosome might originate from incomplete or partial PCM disassembly or from premature recruitment of PCM. Effects on centrosome structure might be direct, as emerin is a component of mitotic centrosomes in Drosophila embryos [84, 85]. This association appears to be conserved, as human emerin is also found in mitotic centrosomes [86, 87]. Further, phosphorylation of Drosophila emerin by Aurora-A kinase is required for mitotic exit in SL2 cells [85], indicating that emerin has a regulatory function at the centrosome. Alternatively, effects of loss of emerin might be indirect, resulting from gene expression changes that alter levels of mitotic regulators. Regardless of mechanism, our data suggest that emerin has a role in PCM regulation. Further investigations are needed to test contributions of emerin to the centrosome cycle in fGSC mitosis.

ATR and Chk2 kinases localize to mitotic centrosomes [88–90]. Studies in human cells indicate that ATR associates with γ-tubulin and influences the kinetics of microtubule formation at centrosomes [88]. Localization of ATR to the centrosome provides a link between mitosis and the DNA damage response. However, DDR proteins localize to centrosomes even in the absence of DNA damage [88, 91], raising the possibility that ATR is a general sensor of structure and function at centrosomes [92]. Building from these observations, we predict that the structurally defective centrosome in emerin mutant fGSCs might be responsible for transmitting signals to ATR and Chk2 kinases, ultimately leading to fGSC loss.

Mutations in NL LEM-D proteins cause diseases linked to compromised stem cell homeostasis [93–96]. Herein, we link centrosome dysfunction with failures in stem cell homeostasis due to mutation of the Drosophila NL protein emerin. Our studies align with observations in human fibroblasts that emerin anchors interphase centrosomes to the nucleus through direct interactions with microtubules [97] and that expression of mutant forms of emerin in HeLa cells causes aberrant nuclear shape and mislocalization of tubulin and centrosomes [98]. Taken together, these observations reinforce connections between emerin and centrosomes. As mechanisms of stem cell homeostasis are shared between cell types and organisms [99], it is possible that other stem cell populations used non-canonical modes of mitosis to ensure robustness of the asymmetric division, which might sensitize division of these cells to defects in the NL composition.

Star Methods

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Pamela Geyer (pamela-geyer@uiowa.edu).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents

Data and Code Availability

No datasets were generated in this study.

Experimental Model and Subject Details Drosophila stocks and culture conditions

Drosophila stocks were raised on standard cornmeal/agar medium with p-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester as a mold inhibitor. All crosses were carried out at 25°C, 70% humidity. In all analyses, the reference strain is y1w67c23 (wild type). The lamin RNAi stock used is y1, sc*, v1, sev21; P[TRiP.GL00577]attP2. Knockdown of Lamin-B in fGSCs was achieved using a nosgal4vp16 driver, and crosses were carried out at 25°C unless otherwise noted. The emerin mutant refers to y1w67c23;oteB279G/PK (emerin Loss of Function, LOF) in which the oteB279G allele carries an insertion of a Piggybac transposon at +764 and the otePK carries a premature stop at codon 127 [38]. The chk2 mutant background refers chk2p6/p30 (chk2 LOF) in which the chk2p6 allele carries a P-element insertion and deletion in the second exon of chk2 that includes the start codon [101] and the chk2p30 allele carries a deletion of the 5’-UTR and first two coding exons [102]. The emerin and chk2 alleles are all null alleles. Other stocks were y w; bafgfp [46] and y1 w*; P[PTT-GB]koiCB04483. Detailed allele information is listed in the Key Resources Table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-Lamin Dm0 | DSHB | ADL84.12 |

| anti-H3S10p | Millipore | Cat#06-570 |

| anti-emerin | Geyer lab | N/A |

| anti-GFP | Abcam | ab5450 |

| anti-Kugelkern | Jörg Grosshans | N/A |

| anti-GP210 | Genetex | GTX15601 |

| anti-RFP | OriGene | AB1140-100 |

| anti-FG Nups (Mab414) | Bio legend | Cat#902901 |

| anti-α-Tubulin | Sero Tech. | MCA78G |

| anti-CP190 | Geyer lab | N/A |

| anti-Asl | Nassar Rusan | N/A |

| anti-Cnn | Nassar Rusan | N/A |

| anti-Vasa | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-26877 |

| anti-Sxl | DSHB | M114 |

| anti-Mei-P26 | Paul Lasko | N/A |

| anti-Stand Stil | D. Pauli | N/A |

| anti-Top2 | Paul Fisher | N/A |

| anti-HP1a | DSHB | C1A9 |

| anti-ɣ-Tubulin | Gregory Rogers | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| y 1 w 67c23 | Bloomington stock center | 6599 |

| y 1, sc*, v 1, sev 21; P[TRiP.GL00577]attP2 | Bloomington stock center | 36617 |

| y 1 w 67c23; ote B279G/CyO,y+ | Bloomington stock center, Geyer lab | 16189 |

| y 1 w 67c23; ote halPK/CyO,y+ | T. Schupbach | N/A |

| y1 w67c23; lokiP30/CyO | Y. Rong | N/A |

| y1 w67c23; lokiP6/CyO | Y. Rong | N/A |

| w;nosgal4vp16 | Bloomington stock center | 4937 |

| y 1 w*; P[PTT-GB]koi CB04483 | Bloomington stock center | 51525 |

| y w; baf gfp | This study | N/A |

| Other | ||

| WGA | Invitrogen | Cat#W32466 |

| 16% EM Grade paraformaldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat#15710 |

| DAPI | Millipore Sigma | Cat#10236276001 |

| SlowFade Diamond mountant | ThermoFisher | Cat#S36967 |

Methods Details

Immunohistochemical analyses

For each experiment, ten pairs of ovaries were dissected from newborn adult females or fifteen pairs of mid-third instar larval ovaries in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution or room temperature for α-Tubulin staining. Dissected tissues were immediately fixed in 4% EM Grade paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min. Ovaries were then washed in 0.3% PBST and blocked in 5% w/v BSA at room temperature for 1 hr. All larval tissues were additionally permeabilized with 1% PBST at room temperature for 1 hr before blocking in BSA. Ovaries were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight for confocal imaging or 48 hours for STED imaging and incubated at room temperature with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 2 hrs for confocal imaging or 4 hrs for STED imaging. Ovaries were then washed in PBST, stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI and mounted in SlowFade for confocal imaging or Prolong diamond for STED imaging. Confocal images were collected with a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope and processed using ZEN imaging software. STED images were collected with a Leica SP8 Confocal/STED microscope and processed with LAS X software. Primary antibodies included: 1) mouse anti-Lamin Dm0 at 1:300, 2) rabbit anti-H3S10p at 1:500, 3) goat anti-emerin at 1:500, 4) goat anti-GFP at 1:2,000, 5) rabbit anti-Kugelkern 1:1,000, 6) mouse anti-GP210 at 1:50, 7) goat anti-RFP at 1:200, 8) mouse anti-FG Nups at 1:500, 9) rat anti-α-Tubulin at 1:40, 10) sheep anti-CP190 at 1:1,000, 11) guinea pig anti-Asl at 1:10,000, 12) rabbit anti-Cnn at 1:10,000, 13) goat anti-Vasa at 1:50, 14) mouse anti-Sxl at 1:10, 15) rabbit anti-Top2 at 1:100, 16) mouse anti-HP1a at 1: 200, 17) mouse anti-α-Tubulin at 1:1,000, 18) Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated WGA at 1:500, 19) rabbit anti-Mei-P26 at 1:500, and 20) rabbit anti-Stand still at 1:4,000. Experiments were performed using at least two biological replicates involving at least ten pairs of ovaries per experiment. Numbers of nuclei examined for each cell type and stage are summarized in the Table S1. Detailed primary antibody information is listed in the Key Resources Table.

Embryo hatching assay

Twenty one-day-old females and ten males were kept in bottles covered with orange juice plates (90% orange juice, 3.6% agar, 1% ethyl acetate) supplemented with wet yeast. Orange juice plates were changed every 24 hrs. Embryos were transferred with a paint brush to double-sided tapes placed on glass slides. Collected embryos were incubated at 25 °C in a wet chamber for an additional 24 hrs. to quantify the number of hatched progeny. Experiments were repeated at least three times.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Image quantification

The distance between centrosomes were quantified in maximum projection images of metaphase and interphase fGSCs from ovaries dissected from newly born females that were stained with antibodies against H3S10p and centrosome markers. The distance between two centrosome spots was measured with the Zen software graphic tool. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using Mann-Whitney U-test. Percentage of embedded centrosomes were quantified in fGSCs of ovaries stained with antibodies against H3S10p and centrosome markers. Embedding was defined as a greater than 50% overlap between the centrosome and Lamin-B. Statistical analysis was performed using Two proportion Z-test. Sizes of the interphase PCM were quantified using ImageJ. Z-stacks were first collapsed with the maximum projection tool. Then, PCM foci were traced along their surface and areas of the foci were recorded. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using Mann-Whitney U-test. Centrosome positioning was quantified in metaphase fGSCs co-stained with antibodies against centrosome markers and H3S10p. Quantification was done by first collapsing Z-stacks with the maximum projection tool. Then a straight line was drawn between the centers of two centrosomes. Lengths of chromosomes at either side of the line were measured, and the ratio of the short versus the long chromosome side was recorded. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using Mann-Whitney U-test. For all box plots, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentile interval, the line represents the median and the whiskers represent the 5th to 95th percentile interval and non-outlier range.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

fGSCs retain a permeable, but intact NE and NL throughout mitosis.

Lamin and emerin are required for spindle structures and chromosome segregation.

Loss of emerin causes retention of PCM and nucleation of aster MTs in interphase.

Alterations of interphase centrosomes are linked to the NL checkpoint activation.

Acknowledgements

We thank current and former members (Lacy Barton and Alexey Soshnev) of the Geyer laboratory for helpful discussions, and members of the Bill Sullivan laboratory (UC Santa Cruz) for the comments on mitotic phenotypes. We thank Paul Fisher (Stony Brook University), Jörg Grosshans (University of Göttingen), Tina Tootle (University of Iowa), Nassar Rusan (NIH), Gregory Rogers (University of Arizona), Lori Wallrath (University of Iowa) and Yokiko Yamashita (University of Michigan) for generously supplying reagents. This work was supported by the NIH R01 funding (GM087341) to PKG. Imaging was supported by the NIH funded University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facility (R01GM987654). This work utilized the Zeiss 710 confocal microscope in the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facilities that was purchased with funding from the NIH SIG grant S10 RR025439-01. The acquisition of the Leica SP8 Laser Scanning Confocal microscope with STED capability was made possible by a generous grant from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, and Wilson KL (2005). The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxley RM, Soshnev AA, Koryakov DE, Zhimulev IF, and Geyer PK (2011). The role of the Suppressor of Hairy-wing insulator protein in Drosophila oogenesis. Dev Biol 356, 398–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman RD, Gruenbaum Y, Moir RD, Shumaker DK, and Spann TP (2002). Nuclear lamins: building blocks of nuclear architecture. Genes Dev 16, 533–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalo S (2014). DNA Damage and Lamins. Cancer Biology and the Nuclear Envelope: Recent Advances May Elucidate Past Paradoxes 773, 377–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke B, and Stewart CL (2014). Functional architecture of the cell’s nucleus in development, aging, and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol 109, 1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong XR, Luperchio TR, and Reddy KL (2014). NET gains and losses: the role of changing nuclear envelope proteomes in genome regulation. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 28, 105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Las Heras JI, Zuleger N, Batrakou DG, Czapiewski R, Kerr AR, and Schirmer EC (2017). Tissue-specific NETs alter genome organization and regulation even in a heterologous system. Nucleus 8, 81–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korfali N, Wilkie GS, Swanson SK, Srsen V, de Las Heras J, Batrakou DG, Malik P, Zuleger N, Kerr AR, Florens L, et al. (2012). The nuclear envelope proteome differs notably between tissues. Nucleus 3, 552–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solovei I, Wang AS, Thanisch K, Schmidt CS, Krebs S, Zwerger M, Cohen TV, Devys D, Foisner R, Peichl L, et al. (2013). LBR and lamin A/C sequentially tether peripheral heterochromatin and inversely regulate differentiation. Cell 152, 584–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith ER, Meng Y, Moore R, Tse JD, Xu AG, and Xu XX (2017). Nuclear envelope structural proteins facilitate nuclear shape changes accompanying embryonic differentiation and fidelity of gene expression. BMC Cell Biol 18, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansz N, and Torres-Padilla ME (2019). Genome activation and architecture in the early mammalian embryo. Curr Opin Genet Dev 55, 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorland YL, Cornelissen AS, Kuijk C, Tol S, Hoogenboezem M, van Buul JD, Nolte MA, Voermans C, and Huveneers S (2019). Nuclear shape, protrusive behaviour and in vivo retention of human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells is controlled by Lamin-A/C expression. Sci Rep 9, 14401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton LJ, Soshnev AA, and Geyer PK (2015). Networking in the nucleus: a spotlight on LEM-domain proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 34, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brachner A, and Foisner R (2011). Evolvement of LEM proteins as chromatin tethers at the nuclear periphery. Biochem Soc Trans 39, 1735–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin F, Blake DL, Callebaut I, Skerjanc IS, Holmer L, McBurney MW, Paulin-Levasseur M, and Worman HJ (2000). MAN1, an inner nuclear membrane protein that shares the LEM domain with lamina-associated polypeptide 2 and emerin. J Biol Chem 275, 4840–4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng R, Ghirlando R, Lee MS, Mizuuchi K, Krause M, and Craigie R (2000). Barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF) bridges DNA in a discrete, higher-order nucleoprotein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 8997–9002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai M, Huang Y, Ghirlando R, Wilson KL, Craigie R, and Clore GM (2001). Solution structure of the constant region of nuclear envelope protein LAP2 reveals two LEM-domain structures: one binds BAF and the other binds DNA. Embo J 20, 4399–4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montes de Oca R, Lee KK, and Wilson KL (2005). Binding of barrier to autointegration factor (BAF) to histone H3 and selected linker histones including H1.1. J Biol Chem 280, 42252–42262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Aguilera C, Ikegami K, Ayuso C, de Luis A, Iniguez M, Cabello J, Lieb JD, and Askjaer P (2014). Genome-wide analysis links emerin to neuromuscular junction activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol 15, R21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrales RR, Forn M, Georgescu PR, Sarkadi Z, and Braun S (2016). Control of heterochromatin localization and silencing by the nuclear membrane protein Lem2. Genes Dev 30, 133–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamin A, and Wiebe MS (2015). Barrier to Autointegration Factor (BANF1): interwoven roles in nuclear structure, genome integrity, innate immunity, stress responses and progeria. Curr Opin Cell Biol 34, 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barkan R, Zahand AJ, Sharabi K, Lamm AT, Feinstein N, Haithcock E, Wilson KL, Liu J, and Gruenbaum Y (2012). Ce-emerin and LEM-2: essential roles in Caenorhabditis elegans development, muscle function, and mitosis. Mol Biol Cell 23, 543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samwer M, Schneider MWG, Hoefler R, Schmalhorst PS, Jude JG, Zuber J, and Gerlich DW (2017). DNA Cross-Bridging Shapes a Single Nucleus from a Set of Mitotic Chromosomes. Cell 170, 956–972 e923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furukawa K, Sugiyama S, Osouda S, Goto H, Inagaki M, Horigome T, Omata S, McConnell M, Fisher PA, and Nishida Y (2003). Barrier-to-autointegration factor plays crucial roles in cell cycle progression and nuclear organization in Drosophila. J Cell Sci 116, 3811–3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haraguchi T, Koujin T, Segura-Totten M, Lee KK, Matsuoka Y, Yoneda Y, Wilson KL, and Hiraoka Y (2001). BAF is required for emerin assembly into the reforming nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci 114, 4575–4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi R, Xu N, Wang G, Ren H, Li S, Lei J, Lin Q, Wang L, Gu X, Zhang H, et al. (2015). The lamin-A/C-LAP2alpha-BAF1 protein complex regulates mitotic spindle assembly and positioning. J Cell Sci 128, 2830–2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zink D, Fischer AH, and Nickerson JA (2004). Nuclear structure in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer 4, 677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scaffidi P, and Misteli T (2006). Lamin A-dependent nuclear defects in human aging. Science 312, 1059–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobrzynska A, Gonzalo S, Shanahan C, and Askjaer P (2016). The nuclear lamina in health and disease. Nucleus 7, 233–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber KH, and Kennedy BK (2013). When lamins go bad: nuclear structure and disease. Cell 152, 1365–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taimen P, Pfleghaar K, Shimi T, Moller D, Ben-Harush K, Erdos MR, Adam SA, Herrmann H, Medalia O, Collins FS, et al. (2009). A progeria mutation reveals functions for lamin A in nuclear assembly, architecture, and chromosome organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 20788–20793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vlcek S, and Foisner R (2007). A-type lamin networks in light of laminopathic diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773, 661–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gotzmann J, and Foisner R (2006). A-type lamin complexes and regenerative potential: a step towards understanding laminopathic diseases? Histochem Cell Biol 125, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohwi M, Lupton JR, Lai SL, Miller MR, and Doe CQ (2013). Developmentally regulated subnuclear genome reorganization restricts neural progenitor competence in Drosophila. Cell 152, 97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandt A, Krohne G, and Grosshans J (2008). The farnesylated nuclear proteins KUGELKERN and LAMIN B promote aging-like phenotypes in Drosophila flies. Aging Cell 7, 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sola-Carvajal A, Revechon G, Helgadottir HT, Whisenant D, Hagblom R, Dohla J, Katajisto P, Brodin D, Fagerstrom-Billai F, Viceconte N, et al. (2019). Accumulation of Progerin Affects the Symmetry of Cell Division and Is Associated with Impaired Wnt Signaling and the Mislocalization of Nuclear Envelope Proteins. J Invest Dermatol 139, 2272–2280 e2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang X, Xia L, Chen D, Yang Y, Huang H, Yang L, Zhao Q, Shen L, Wang J, and Chen D (2008). Otefin, a nuclear membrane protein, determines the fate of germline stem cells in Drosophila via interaction with Smad complexes. Dev Cell 14, 494–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barton LJ, Pinto BS, Wallrath LL, and Geyer PK (2013). The Drosophila nuclear lamina protein otefin is required for germline stem cell survival. Dev Cell 25, 645–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinto BS, Wilmington SR, Hornick EE, Wallrath LL, and Geyer PK (2008). Tissue-specific defects are caused by loss of the drosophila MAN1 LEM domain protein. Genetics 180, 133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barton LJ, Lovander KE, Pinto BS, and Geyer PK (2016). Drosophila male and female germline stem cell niches require the nuclear lamina protein Otefin. Dev Biol 415, 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barton LJ, Duan T, Ke W, Luttinger A, Lovander KE, Soshnev AA, and Geyer PK (2018). Nuclear lamina dysfunction triggers a germline stem cell checkpoint. Nat Commun 9, 3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Rusinol A, Sinensky M, Wang Y, and Zou Y (2006). DNA damage responses in progeroid syndromes arise from defective maturation of prelamin A. J Cell Sci 119, 4644–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varela I, Cadinanos J, Pendas AM, Gutierrez-Fernandez A, Folgueras AR, Sanchez LM, Zhou Z, Rodriguez FJ, Stewart CL, Vega JA, et al. (2005). Accelerated ageing in mice deficient in Zmpste24 protease is linked to p53 signalling activation. Nature 437, 564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu B, Wang J, Chan KM, Tjia WM, Deng W, Guan X, Huang JD, Li KM, Chau PY, Chen DJ, et al. (2005). Genomic instability in laminopathy-based premature aging. Nat Med 11, 780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimi T, and Goldman RD (2014). Nuclear lamins and oxidative stress in cell proliferation and longevity. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 773, 415–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duan T, Kitzman SC, and Geyer PK (2020). Survival of Drosophila germline stem cells requires the chromatin binding protein Barrier-to-autointegration factor. Development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng W, and Lin H (1997). Spectrosomes and fusomes anchor mitotic spindles during asymmetric germ cell divisions and facilitate the formation of a polarized microtubule array for oocyte specification in Drosophila. Dev Biol 189, 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson JO, Chen C, and Yamashita YM (2019). Germline stem cell homeostasis. Curr Top Dev Biol 135, 203–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duan T, Green N, Tootle TL, and Geyer PK (2020). Nuclear architecture as an intrinsic regulator of Drosophila female germline stem cell maintenance. Curr Opin Insect Sci 37, 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ungricht R, and Kutay U (2017). Mechanisms and functions of nuclear envelope remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18, 229–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilboa L, and Lehmann R (2006). Soma-germline interactions coordinate homeostasis and growth in the Drosophila gonad. Nature 443, 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dansereau DA, and Lasko P (2008). The development of germline stem cells in Drosophila. Methods Mol Biol 450, 3–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barton LJ, Wilmington SR, Martin MJ, Skopec HM, Lovander KE, Pinto BS, and Geyer PK (2014). Unique and Shared Functions of Nuclear Lamina LEM Domain Proteins in Drosophila. Genetics 197, 653–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gorjanacz M, Klerkx EP, Galy V, Santarella R, Lopez-Iglesias C, Askjaer P, and Mattaj IW (2007). Caenorhabditis elegans BAF-1 and its kinase VRK-1 participate directly in post-mitotic nuclear envelope assembly. Embo J 26, 132–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molitor TP, and Traktman P (2014). Depletion of the protein kinase VRK1 disrupts nuclear envelope morphology and leads to BAF retention on mitotic chromosomes. Mol Biol Cell 25, 891–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon DN, and Wilson KL (2011). The nucleoskeleton as a genome-associated dynamic ‘network of networks’. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12, 695–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osmanagic-Myers S, Dechat T, and Foisner R (2015). Lamins at the crossroads of mechanosignaling. Genes Dev 29, 225–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Souza CP, and Osmani SA (2007). Mitosis, not just open or closed. Eukaryot Cell 6, 1521–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rothballer A, and Kutay U (2012). SnapShot: the nuclear envelope II. Cell 150, 1084–1084 e1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paddy MR, Belmont AS, Saumweber H, Agard DA, and Sedat JW (1990). Interphase nuclear envelope lamins form a discontinuous network that interacts with only a fraction of the chromatin in the nuclear periphery. Cell 62, 89–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paddy MR, Saumweber H, Agard DA, and Sedat JW (1996). Time-resolved, in vivo studies of mitotic spindle formation and nuclear lamina breakdown in Drosophila early embryos. J Cell Sci 109 (Pt 3), 591–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burakov AV, and Nadezhdina ES (2013). Association of nucleus and centrosome: magnet or velcro? Cell Biol Int 37, 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Razafsky D, Ward C, Potter C, Zhu W, Xue Y, Kefalov VJ, Fong LG, Young SG, and Hodzic D (2016). Lamin B1 and lamin B2 are long-lived proteins with distinct functions in retinal development. Mol Biol Cell 27, 1928–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim Y, Zheng X, and Zheng Y (2013). Proliferation and differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells lacking all lamins. Cell Res 23, 1420–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abdu U, Brodsky M, and Schupbach T (2002). Activation of a meiotic checkpoint during Drosophila oogenesis regulates the translation of Gurken through Chk2/Mnk. Curr Biol 12, 1645–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Conduit PT, Richens JH, Wainman A, Holder J, Vicente CC, Pratt MB, Dix CI, Novak ZA, Dobbie IM, Schermelleh L, et al. (2014). A molecular mechanism of mitotic centrosome assembly in Drosophila. Elife 3, e03399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borsos M, and Torres-Padilla ME (2016). Building up the nucleus: nuclear organization in the establishment of totipotency and pluripotency during mammalian development. Genes Dev 30, 611–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gesson K, Vidak S, and Foisner R (2014). Lamina-associated polypeptide (LAP)2alpha and nucleoplasmic lamins in adult stem cell regulation and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol 29, 116–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gotic I, Schmidt WM, Biadasiewicz K, Leschnik M, Spilka R, Braun J, Stewart CL, and Foisner R (2010). Loss of LAP2 alpha delays satellite cell differentiation and affects postnatal fiber-type determination. Stem Cells 28, 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen H, Chen X, and Zheng Y (2013). The nuclear lamina regulates germline stem cell niche organization via modulation of EGFR signaling. Cell Stem Cell 13, 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petrovsky R, and Grosshans J (2018). Expression of lamina proteins Lamin and Kugelkern suppresses stem cell proliferation. Nucleus 9, 104–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosengardten Y, McKenna T, Grochova D, and Eriksson M (2011). Stem cell depletion in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Aging Cell 10, 1011–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Webster M, Witkin KL, and Cohen-Fix O (2009). Sizing up the nucleus: nuclear shape, size and nuclear-envelope assembly. J Cell Sci 122, 1477–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samson C, Petitalot A, Celli F, Herrada I, Ropars V, Le Du MH, Nhiri N, Jacquet E, Arteni AA, Buendia B, et al. (2018). Structural analysis of the ternary complex between lamin A/C, BAF and emerin identifies an interface disrupted in autosomal recessive progeroid diseases. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 10460–10473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Civelekoglu-Scholey G, Tao L, Brust-Mascher I, Wollman R, and Scholey JM (2010). Prometaphase spindle maintenance by an antagonistic motor-dependent force balance made robust by a disassembling lamin-B envelope. J Cell Biol 188, 49–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsai MY, Wang S, Heidinger JM, Shumaker DK, Adam SA, Goldman RD, and Zheng Y (2006). A mitotic lamin B matrix induced by RanGTP required for spindle assembly. Science 311, 1887–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo Y, and Zheng Y (2015). Lamins position the nuclear pores and centrosomes by modulating dynein. Mol Biol Cell 26, 3379–3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fichelson P, Moch C, Ivanovitch K, Martin C, Sidor CM, Lepesant JA, Bellaiche Y, and Huynh JR (2009). Live-imaging of single stem cells within their niche reveals that a U3snoRNP component segregates asymmetrically and is required for self-renewal in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol 11, 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Q, Shalaby NA, and Buszczak M (2014). Changes in rRNA transcription influence proliferation and cell fate within a stem cell lineage. Science 343, 298–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fuentealba LC, Eivers E, Geissert D, Taelman V, and De Robertis EM (2008). Asymmetric mitosis: Unequal segregation of proteins destined for degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 7732–7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lattao R, Kovacs L, and Glover DM (2017). The Centrioles, Centrosomes, Basal Bodies, and Cilia of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 206, 33–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Magescas J, Zonka JC, and Feldman JL (2019). A two-step mechanism for the inactivation of microtubule organizing center function at the centrosome. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moura M, and Conde C (2019). Phosphatases in Mitosis: Roles and Regulation. Biomolecules 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Muller H, Schmidt D, Steinbrink S, Mirgorodskaya E, Lehmann V, Habermann K, Dreher F, Gustavsson N, Kessler T, Lehrach H, et al. (2010). Proteomic and functional analysis of the mitotic Drosophila centrosome. EMBO J 29, 3344–3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Habermann K, Mirgorodskaya E, Gobom J, Lehmann V, Muller H, Blumlein K, Deery MJ, Czogiel I, Erdmann C, Ralser M, et al. (2012). Functional analysis of centrosomal kinase substrates in Drosophila melanogaster reveals a new function of the nuclear envelope component otefin in cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol 32, 3554–3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andersen JS, Wilkinson CJ, Mayor T, Mortensen P, Nigg EA, and Mann M (2003). Proteomic characterization of the human centrosome by protein correlation profiling. Nature 426, 570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moser B, Basilio J, Gotzmann J, Brachner A, and Foisner R (2020). Comparative Interactome Analysis of Emerin, MAN1 and LEM2 Reveals a Unique Role for LEM2 in Nucleotide Excision Repair. Cells 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang S, Hemmerich P, and Grosse F (2007). Centrosomal localization of DNA damage checkpoint proteins. J Cell Biochem 101, 451–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takada S, Kelkar A, and Theurkauf WE (2003). Drosophila checkpoint kinase 2 couples centrosome function and spindle assembly to genomic integrity. Cell 113, 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mullee LI, and Morrison CG (2016). Centrosomes in the DNA damage response-the hub outside the centre. Chromosome Res 24, 35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Takada S, Collins ER, and Kurahashi K (2015). The FHA domain determines Drosophila Chk2/Mnk localization to key mitotic structures and is essential for early embryonic DNA damage responses. Mol Biol Cell 26, 1811–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kidiyoor GR, Kumar A, and Foiani M (2016). ATR-mediated regulation of nuclear and cellular plasticity. DNA Repair (Amst) 44, 143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shimi T, Butin-Israeli V, Adam SA, Hamanaka RB, Goldman AE, Lucas CA, Shumaker DK, Kosak ST, Chandel NS, and Goldman RD (2011). The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev 25, 2579–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chandra T, Ewels PA, Schoenfelder S, Furlan-Magaril M, Wingett SW, Kirschner K, Thuret JY, Andrews S, Fraser P, and Reik W (2015). Global reorganization of the nuclear landscape in senescent cells. Cell Rep 10, 471–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barascu A, Le Chalony C, Pennarun G, Genet D, Zaarour N, and Bertrand P (2012). Oxydative stress alters nuclear shape through lamins dysregulation: a route to senescence. Nucleus 3, 411–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dreesen O, Chojnowski A, Ong PF, Zhao TY, Common JE, Lunny D, Lane EB, Lee SJ, Vardy LA, Stewart CL, et al. (2013). Lamin B1 fluctuations have differential effects on cellular proliferation and senescence. J Cell Biol 200, 605–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Salpingidou G, Smertenko A, Hausmanowa-Petrucewicz I, Hussey PJ, and Hutchison CJ (2007). A novel role for the nuclear membrane protein emerin in association of the centrosome to the outer nuclear membrane. J Cell Biol 178, 897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dubinska-Magiera M, Koziol K, Machowska M, Piekarowicz K, Filipczak D, and Rzepecki R (2019). Emerin Is Required for Proper Nucleus Reassembly after Mitosis: Implications for New Pathogenetic Mechanisms for Laminopathies Detected in EDMD1 Patients. Cells 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Morrison SJ, and Spradling AC (2008). Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 132, 598–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]