Abstract

The corneal endothelial monolayer and associated Descemet’s membrane (DM) complex is a unique structure that plays an essential role in corneal function. Endothelial cells are neural crest derived cells that rest on a special extracellular matrix and play a major role in maintaining stromal hydration within a narrow physiologic range necessary for clear vision. A number of diseases affect the endothelial cells and DM complex and can impair corneal function and vision. This review addresses different human corneal endothelial diseases characterized by loss of endothelial function including: Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD), congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED), bullous keratopathy, iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome, post-traumatic fibrous downgrowth, glaucoma and diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Fuchs corneal endothelial dystrophy, endothelial disease, stroma, edema, fibrosis

1. Introduction

The corneal endothelium, together with the barrier function of the epithelium and the unique structural properties of the stroma, are responsible for maintaining corneal transparency. The endothelial monolayer consists of closely interdigitated hexagonal-shaped cells with non-continuous apical tight junctions.(Edelhauser, 2006; Mishima, 1982) Humans are born with roughly 5000 endothelial cells/mm2 which gradually decline over time, reaching on average 2400 cells/mm2 in adulthood.(Edelhauser, 2006; Laule et al., 1978; Mishima, 1982) Descemet membrane (DM), the basement membrane of the endothelial monolayer, consists of an anterior banded layer (formed in utero) and a posterior non-banded layer. At birth, the membrane is roughly 3 μm and slowly thickens as it lays down more amorphous material on the endothelial side. This posterior layer continues to thicken throughout life.(de Oliveira and Wilson, 2020) By adulthood the membrane is 10–12 μm thick.

The main function of the corneal endothelium is to keep the stroma within a narrow level of hydration for normal vision. Aqueous humor containing nutrients passively diffuse into the stroma due to the imbibition pressure created by hydrophilic proteoglycans and the leaky endothelial barrier.(Klyce, 2020) Ion transporters within corneal endothelial cells actively offset this diffusion gradient and transport substrates from the stroma to the aqueous humor. The Na+/K+ ATPase pump drives Na+:2HCO3− cotransport with the basolateral sodium bicarbonate cotransporter NBCe1, and also encourages Na+/H+ exchange (NHE).(Klyce, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Nguyen and Bonanno, 2011) NBCe1, NHE, HCO3−, and carbonic anhydrase create a pH buffer by which a lactate osmotic gradient can drive efflux of water.(Li et al., 2020) Additional ion exchange is mediated by Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1), Cl−/HCO3− exchanger, solute carrier family 4 member 11 (SLC4A11) and monocarboxylate transporters 1, 2, and 4.(Bonanno, 2003; Jalimarada et al., 2014) Endothelial cell damage leads to increased endothelial cell layer permeability which overwhelms endothelial cell pump activity.(Bonanno, 2003) Inability to maintain deturgescence causes the stroma to become thick, swollen, and hazy, leading to vision loss.

In humans and other species, corneal endothelial cells are arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle.(Joyce et al., 2002) This lack of replicative potential has immense consequences in clinical settings. When endothelial loss through disease or injury is severe enough to affect visual function, endothelial replacement surgeries are needed to regain corneal clarity.

In this review, we explore the most common endothelial disorders that result in corneal stromal edema and decreased vision: Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD), congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED), bullous keratopathy, iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome, post-traumatic fibrous downgrowth, glaucoma and diabetes mellitus. FECD is covered in great detail given the wealth of information known. All of these disorders demonstrate similar pathophysiology including increased endothelial cell loss, DM thickening or additional membrane formation, and transformation of endothelial cells to a replicative state. Many involve the same genes and proteins, but different mutations or altered expression manifest in different diseases.

2. Endothelial Dystrophies

2.1. Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy

Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy is a slowly progressive, bilateral disease predominately seen in women in their fifth or sixth decades of life. It is the most common indication for endothelial transplantation in the United States.(Musch et al., 2011; Sarnicola et al., 2019) First recognized by Ernst Fuchs in 1910, the original cases exhibited central corneal clouding, loss of corneal sensation, and formation of epithelial bullae. (Eghrari and Gottsch, 2010; Jun, 2010). Closer examination reveals endothelial cell loss and formation of guttae which are excrescences of extracellular matrix products in DM. In the more common late-onset form, patients present with corneal guttae in their early 40s, but are asymptomatic. Over time, patients experience blurred vision as a result of the onset and progression of corneal edema and require treatment. A rarer early-onset form of FECD appears in the early decades of life and progress similarly to the classic type of FECD.

On specular microscopy, endothelial cells demonstrate increased cell size (polymegethism) and irregularity (polymorphism); guttae appear as dark shadows (Fig. 1B).(Elhalis et al., 2010) Descemet membrane is also affected and appears abnormally thick due to increased extracellular matrix material deposition. Endothelial pigmentation may also appear as the cells act as functional macrophages. Cases of chronic and advanced uncontrolled swelling may lead to painful bullae and subepithelial fibrosis that may affect the long-term visual outcomes after endothelial transplants.(Espana and Huang, 2010; Patel et al., 2012) (Figs. 1A, 1C) Initially, FECD may be treated with hypertonic sodium chloride drops and ointment to reverse corneal edema. Severe cases may require corneal transplantation.

Figure 1.

A) Clinical appearance of FECD cornea with edema and areas of fibrosis in subepithelial area impairing vision. B) Endothelial cells decreased in number and presence of guttae is seen in this specular microscopy photograph, does not correspond to Figs. 1A and 1C. C) Anterior segment imaging using Optical Coherence Tomography shows corneal edema and areas of fibrosis, shown by arrows.

Just as the advent of the biomicroscope slit lamp permitted the discovery of FECD, advances in genetic and molecular analysis have brought to light the complex pathophysiology of this disease. However, the etiology of FECD is still incompletely understood. In this section, we discuss the clinical features, risk factors, molecular mechanisms, and genes which have been implicated in FECD. Innovative treatments will likely rest on a comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease.

2.1a. Corneal Guttae and Progression to Symptomatic Edema

The different clinical manifestations of guttae lend to an understanding of progression to visually significant corneal edema. “Primary corneal guttata”, or primary central corneal guttata, is defined as the presence of persistent excrescences in central DM that rarely advances to FECD over time.(Matthaei et al., 2019; Zoega et al., 2013) Given the occasional progression of “primary cornea guttata” to FECD, some believe that “primary cornea guttata” may be a precursor of FECD.(Higa et al., 2011) Others suggest that severe primary corneal guttata should be defined as early FECD.(Adamis et al., 1993; Kitagawa et al., 2002; Nagaki et al., 1996) Further research will determine the relationship between “primary corneal guttata” to FECD and the factors that determine clinical progression. Secondary corneal guttae, or pseudoguttae, are areas of endothelial edema arising from degenerative corneal disease, trauma, or inflammation which resolve after treating the underlying problem.(Higa et al., 2011; Moshirfar et al., 2019) Hassall-Henle bodies are small transparent growths in peripheral DM of normal aging corneal tissue with no clinical implications.(Higa et al., 2011) Finally, in FECD, progressive guttae formation in the central and peripheral DM, and sufficient endothelial cell loss cause stromal edema and light scatter with subsequent blurred vision.(Matthaei et al., 2019; Zoega et al., 2013)

2.1b. FECD Epidemiology

Studies suggest that the prevalence of guttae and FECD varies by race and geographic location. A study from Iceland examining a white population greater than 55 years of age found the prevalence of “primary cornea guttata” to be 11% in females and 7% in males.(Zoega et al., 2013; Zoega et al., 2006) In contrast, the prevalence of “primary corneal guttata” in Japan is about 4%.(Higa et al., 2011; Nagaki et al., 1996) The incidence of FECD in Japan, estimated by the reported number of corneal transplants for FECD, is 0.5%.(Kitagawa et al., 2002; Musch et al., 2011; Santo et al., 1995) Meanwhile, guttae occurs in up to 4% of patients older than 40 years of age in the U.S.(Krachmer et al., 1978; Musch et al., 2011; Sarnicola et al., 2019).

Despite a similar incidence of guttae to a Japanese population, corneal transplantation for FECD in the U.S. is much higher and accounts for 36% of all transplants performed, according to the Eye Bank Association of America.(EBAA, 2020; Musch et al., 2011; Sarnicola et al., 2019) Therefore it is thought that FECD has a higher prevalence in Europe and the United States compared to the rest of the world based on the number of corneal transplants conducted.(Eghrari and Gottsch, 2010) Given the data, it is possible that environmental, dietary, anatomical or genetic factors influence progression from “primary corneal guttata” to FECD in Caucasian populations.

2.1c. Environmental Risk Factors

The environment may play a role in the formation of guttae and FECD. The quiescent nature of endothelial cells makes them susceptible to cumulative damage by physical factors including ultraviolet radiation. Recently Liu et al using C57BL/6 wild-type mice elegantly demonstrated that corneal exposure to ultraviolet light A recapitulates the morphological phenotype seen in endothelial cells with FECD and that those changes were more common in females.(Liu et al., 2020) A comparison of Japanese residents and Chinese Singaporean residents with “primary corneal guttata” found fewer guttae and a higher cell density in the Japanese group compared to the Singaporean group, which the authors attributed to UV exposure and temperature at different latitudes.(Kitagawa et al., 2002) However, it is not clear that UV exposure is the primary cause or the only mediator of FECD. Examination of arc welders, a group frequently exposed to extreme UV light radiation, do not manifest endothelial cell changes such as polymegethism or pleomorphism, which suggests UV light may affect the endothelium only if in conjunction with other factors.(Oblak and Doughty, 2002)

Smoking has been correlated with FECD in some populations. In Iceland, a 20-pack year smoking history (i.e., one pack per day for 20 years or two packs per day for 10 years) was associated with an increased number of corneal guttae.(Zoega et al., 2006) Examination of a large cohort of Caucasians found that smoking increased the odds of developing advanced FECD (grade 4–6) by 30%.(Zhang et al., 2013) Conversely, examination of a Japanese population did not find a connection between smoking and guttae.(Higa et al., 2011) While the results of population studies have been inconsistent, there is evidence that smoking increases oxidative damage in corneal tissue and could accelerate endothelial cell apoptosis in FECD.(Zhang et al., 2013)

Diet is another potential risk factor under investigation.(Ong Tone et al., 2020) Environmental pollutants and temperature changes also could affect FECD through epigenetic modification.(Ong Tone et al., 2020)

2.1d. Molecular Mechanisms Affecting Corneal Endothelial Cell Biology

The exact pathogenesis of FECD is still unclear but evidence points to several cellular changes including alterations in the extracellular matrix, epigenetic modifications, endothelial-mesenchymal transition, cell apoptosis, cellular stress, and the unfolded protein response. A summary of these mechanisms is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Changes of Descemet Membrane and Endothelium in Endothelial Diseases and Decompensation

| Disease | Observed Changes |

|---|---|

| FECD | • Endothelial cell pleomorphism and polymegethism • Upregulation of extracellular matrix proteins of DM and endothelium ∘ Protein accumulation in guttae and endothelial cells ∘DM thickening ∘Accumulation of disorganized matrix proteins • Altered protein expression via epigenetic modification • Endothelial-mesenchymal transition of endothelial cells • Endothelial cell apoptosis via oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, unfolded protein response • Multiple gene mutations which alter endothelial cell structure and function |

| PPCD | • Multiple gene mutations which promote endothelial to mesenchymal transition |

| CHED | • Poor cell adhesion to DM • DM thickening • Increased reactive oxygen species • Early endothelial cell loss |

| Bullous keratopathies | • Formation of a membrane posterior to DM • Upregulation of extracellular matrix proteins of DM and endothelium • Endothelial cell damage by oxidative stress |

| ICE syndrome | • Epithelial-like transformation or metaplasia of endothelial cells |

| Post-traumatic fibrous downgrowth | • Formation of a membrane posterior to DM • Endothelial-mesenchymal transition of endothelial cells |

| Glaucoma | • Endothelial cell loss |

| Diabetes Mellitus | • Endothelial cell pleomorphism and polymegethism • Endothelial cell loss • Endothelial cell mitochondria dysfunction • Decreased endothelial cell pump function • Loss of cell tight-junction formation |

FECD = Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy; DM = Descemet Membrane; PPCD = Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy; CHED = Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy; ICE = Iridocorneal Endothelial

Alterations in the extracellular matrix

Given that endothelial cells secrete the extracellular matrix of DM and matrix composition in turn influences cell behavior (de Oliveira and Wilson, 2020), various studies have investigated the changes noted in the corneal stromal matrix in FECD.(Poulsen et al., 2014; Weller et al., 2014) Gene array analysis and immunohistochemistry of FECD tissue have shown abnormalities in matrix composition and upregulation of different matrix proteins including collagens I, III, XVI, fibronectin, agrin, transforming growth factor beta-induced protein (TGFBIP), and integrin α4.(Weller et al., 2014) Proteins involved in basement membrane formation are also substantially upregulated in DM and endothelium, which correlates well with observed DM thickening.(Poulsen et al., 2014) This evidence supports the idea that a dysfunctional extracellular matrix contributes to morphological changes in FECD. The composition of guttae remains unclear but studies have shown overexpression of TGFBIP and clusterin, a chaperone protein that aids in protein folding, in endothelial cells (Jurkunas et al., 2008; Kuot et al., 2012) and co-localization of both in guttae.(Jurkunas et al., 2009)

Similarly, extracellular matrix alterations likely occur in early-onset FECD where changes in DM structure are found. Comparison of corneal tissue from early-onset FECD with a L450W mutation in the collagen VIII alpha-2 polypeptide (COL8A2) to late-onset FECD and normal controls showed that early-onset FECD have thicker DM with an anterior banded layer three times thicker than normal, and traversed by refractile strands and blebs reactive to COL8A2. There is also increased basement membrane components: collagen IV, fibronectin, and laminin.(Gottsch et al., 2005b) Both early and late-onset FECD have an accumulation of disorganized collagen VIII in refractile, fibrous structures in the anterior fetal layer.(Gottsch et al., 2005b) In summary, dysregulation and abnormal deposition of extracellular matrix components, a fibrosis-like process, is a common finding in both early and late-onset FECD. A better understanding of the mechanisms regulating matrix formation opens possibilities for pharmaceutical or genetic engineering of matrix protein expression.

Epigenetic modifications (DNA methylation and miRNAs)

Recent studies suggest that epigenetic modifications may play a role in the manifestation of late-onset FECD and may provide an option for therapy. Epigenetic modifications are heritable alterations in gene expression that do not alter the DNA sequence itself. Epigenetic modifications may explain the phenotype differences seen with identical genotypes. Genome-wide DNA methylation arrays have identified several differentially methylated probes which affect proteins involved in cytoskeletal organization, ion transport, and cellular metabolism in FECD.(Khuc et al., 2017) This suggests that multiple modifications in basic cell function could be required to manifest FECD. Interestingly, FECD tissue demonstrates repression of miRNAs miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-2–5p and miR-29c-5p and upregulation of their downstream targets collagens I, IV, and laminin.(Matthaei et al., 2014) MiR-199B was found to be highly hypermethylated in these arrays, causing down-regulation of its downstream product miR-199–5p and increased expression of target genes Snai1 and ZEB1, which control extracellular matrix production.(Pan et al., 2019). These findings suggest that abnormal DNA methylation of miRNA gene promoters may contribute to increased extracellular matrix deposition seen in FECD and could open pathways for pharmacological manipulation.

Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EnT)

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is a normal cellular phenomenon during tissue and organ development as well as other biological processes.(Nieto et al., 2016) It is suspected to play a role in the pathogenesis of FECD. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is most commonly referred in the scientific literature as EMT, but since we are referring to endothelial cells in the case of FECD, where the transformation of endothelial to mesenchymal transition occurs, we will use the term EnT. During EnT, cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions are abnormal, which leads to the activation of endothelial cells with loss of cell polarity and detachment from basement membrane, and acquisition of mesenchymal properties including increased synthesis of collagen I and fibronectin.(Nieto et al., 2016) These transformed endothelial cells behave like stromal fibroblasts which are able to deposit matrix in large quantities. Different researchers have demonstrated EnT in early- and late-onset FECD. Okumura et al have demonstrated that epithelial to mesenchymal transition-inducing genes ZEB, zinc-finger E-box binding homeobox 1, and SNAI1, Snail 1, were highly expressed in cultured immortalized endothelial cells obtained from normal and FECD corneas. Stimulation by transforming growth factor beta 1 greatly increased extracellular matrix production in FECD endothelial cells but not in normal endothelial cells.(Okumura et al., 2015) Similarly, in FECD endothelial cells levels of the microRNA (miR)-29 family, a down-regulator of extracellular matrix, are decreased which causes increased production of collagens I, IV and laminin.(Matthaei et al., 2014; Toyono et al., 2016) Oxidative stress, another hypothetical cause of FECD, can also induce EnT in endothelial cells from patients with FECD and could stimulate the abnormal deposition of matrix.(Katikireddy et al., 2018) In conclusion, the process of EnT encourages abnormal extracellular matrix formation and deposition and is potentially worsened by oxidative stress.

Cell Apoptosis, Oxidative stress, and Mitochondrial Fragmentation

Different mechanisms including oxidative stress, mitophagy and apoptosis may explain the high rate of endothelial cell loss seen in FECD. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial dysfunction, mitophagy, and cell death. Due to the high mitochondrial activity and generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) as part of high metabolic processes for ATP generation during endothelial pump function, mitochondrial DNA is highly susceptible to oxidative damage. Besides, mitochondrial DNA lacks protective and repair mechanisms, creating conditions for mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death. Studies have demonstrated increased ROS byproducts such as nitrotyrosine, and markers for oxidative stress such as 8-OHdG in FECD.(Ong Tone et al., 2020) Generation of ROS can oxidize DNA and induce mutagenesis in the mitochondrial DNA causing mitochondrial dysfunction and cell apoptosis. In FECD cells, there is a larger accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and nuclear DNA damage when compared to controls.(Halilovic et al., 2016)

It is well established that corneal endothelial cells in FECD undergo a higher rate of apoptosis.(Borderie et al., 2000) Increased apoptosis is noted in epithelial cells and keratocytes in FECD as well.(Li et al., 2001) Elevated extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic markers, such as Fas, FasL, Bcl-2 and Bax, are found in all layers of the cornea in FECD.(Li et al., 2001) Caspase 3 and 9 apoptotic signaling proteins also demonstrate increased activity in FECD.(Engler et al., 2010a; Engler et al., 2010b) Additionally, oxidative stress may cause FECD cells to be more susceptible to p53-regulated apoptosis.(Azizi et al., 2011). Future treatments for FECD may be directed at alleviating ROS formation and preventing mitochondrial damage. Elamipretide, a peptide that increases mitochondrial respiration, electron transport and ATP generation, has been investigated in treatment of other diseases with mitochondrial dysfunction and could be of potential use in FECD.(Okumura et al., 2018)

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the Unfolded Protein Response

It is also thought that the unfolded protein response (UPR) may contribute to endothelial cell loss in FECD. The endoplasmic reticulum is responsible for protein folding and synthesis. Accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum can lead to endoplasmic reticulum stress. UPR is responsible for clearing misfolded proteins, but prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress may trigger apoptosis instead. In late-onset FECD, the endoplasmic reticulum demonstrates an enlarged endoplasmic reticulum and cells express increased UPR stress markers (GRP78, phospho-eIF2α, CHOP) and apoptosis markers (caspase 3 and 9).(Engler et al., 2010a)

Multiple gene mutations may cause increased endothelial cell apoptosis via UPR. In late-onset FECD, three missense mutations in the gene SLC4A11, encoding solute carrier family 4 member 11, were found to induce aberrant glycosylation and cellular localization to the cell surface with abnormal protein folding (Table 2).(Vithana et al., 2007) Abnormal protein folding and poor cell membrane tracking have been identified in other SLC4A11 point mutations.(Alka and Casey, 2018) Similarly, mutant lipoxygenase homology domain-containing protein 1 (LOXHD1) precipitates are observed in FECD tissue, which may cause an aggregation defect or cytotoxic effect.(Riazuddin et al., 2012) Increased expression of transforming growth factor beta has also been linked to UPR activation.(Okumura et al., 2019) In early onset FECD, patients with the COL8A2 L450W mutation have increased COL8A2 in the ribosomal layer of the endoplasmic reticulum.(Zhang et al., 2006) In mouse models, both the COL8A2 L450W and Q455K knock-in mice exhibit markers of UPR activation and apoptosis.(Meng et al., 2013) These findings suggest that future treatments for FECD may be directed towards reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress.(Kim et al., 2014) Lithium, explored as a potential treatment for neurodegenerative diseases, has been shown to improve endothelial cell numbers in vitro and in mouse models.(Kim et al., 2013) N-acetylcysteine has also demonstrated reversal of apoptosis proteins in the L450W knock-in mouse model.(Kim et al., 2014)

Table 2.

Genetic Mutations Observed in Endothelial Disease

| Gene | Cytogenetic Location | Associated Mutations | Protein | Function | Associated Phenotype(s) | Select References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL8A2 | 1p34.3 | L450W Q455K Q455V |

Collagen alpha-2(VIII) chain | Extracellular matrix protein | Early-onset FECD PPCD |

Gottsch et al., 2005a Biswas et al., 2001 Mok et al., 2009 |

| TCF4 | 18q21.2 | Expanded CTG TNR rs613872 Other SNP |

Transcription factor 4 (or E2-2) | Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor | FECD |

Baratz et al., 2010 Murre et al., 1994 Wieben et al., 2012 |

| ZEB1 | 10p11.22 |

FECD N78T Q810P Q840P A905G P649A Other mutations PPCD c.953_954insA c.1506dupA c.1592delA c.3012_3013delAG Gln12X Gln214X Arg325X Met1Arg |

Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 domain (or TCF8) | DNA binding transcription factor activity Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

FECD PPCD |

Riazuddin et al., 2010b Zhang et al., 2019 Aldave et al., 2007 |

| SLC4A11 | 20p13 | 60+ mutations | Solute carrier family 4 member 11 (or sodium bicarbonate transporter- protein 11) | Water and ion transport | FECD CHED Harboyan Syndrome |

Li et al., 2019 Vilas et al., 2013 Loganathan et al., 2016 Malhotra et al., 2019 Guha et al., 2017 VIthana et al., 2007 Alka and Casey, 2018 Riazuddin et al., 2010a Hand et al., 1999 Jiao et al., 2007 VIthana et al., 2006 Siddiqui et al., 2014 |

| LOXHD1 | 18q21.1 | R547C Other mutations |

Lipoxygenase homology domain-containing protein 1 | Protein targeting to cell membranes | FECD |

Riazuddin et al., 2012 Zhang et al., 2019 |

| AGBL1 | 15q25.3 | R1028* C990S |

ATP/GTP binding protein like 1 | Protein deglutamylation | FECD | Riazuddin et al., 2013 |

| RAD51 | 15q15.1 | rs1801321 | RAD51 recombinase | DNA double strand break repair | FECD | Synowiec et al., 2013 |

| FEN1 | 11q12.2 | rs424615 rs174538 |

Flap endonuclease 1 | Base excision repair | FECD | Wojcik et al., 2014 |

| XRCC1 | 19q13.31 | rs25487 | X-ray repair cross complementing 1 | Scaffold protein for base excision repair proteins | FECD | Wójcik et al., 2015 |

| NEIL1 | 15q24.2 | rs4462560 | Nei endonuclease VIII-like 1 | Base excision repair | FECD | Wójcik et al., 2015 |

| LIG3 | 17q12 | rs1052536 rs3135967 |

DNA ligase 3 | Base excision repair | FECD | Synowiec et al., 2015 |

| OVOL2 | 20p11.23 | c.-339_361dup c.-370T>C c.-274T>G c.-307T>C |

Ovo like zinc finger 2 | Zinc-finger transcription factor Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition | PPCD |

Davidson et al., 2016 Chung et al., 2017 |

| GRHL2 | 8q22.3 | c.20+544G>T c.20+257delT c.20+133delA |

Grainyhead like transcription factor | Transcription factor Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition | PPCD | Liskova et al., 2018 |

FECD = Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy; PPCD = Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy; CHED = Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy; TNR = trinucleotide repeat; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism

2.1e. Genes associated with FECD

FECD is thought to have either a sporadic presentation or autosomal dominant inheritance. The IC3D classification describes FECD as of more common sporadic inheritance (Weiss et al., 2015) whereas incomplete penetrance and expressivity along with late-onset disease presentation have made some cases difficult to classify as of spontaneous origin or autosomal dominant inheritance.(Sarnicola et al., 2019; Vedana et al., 2016; Weiss et al., 2015) The most widely described genetic changes associated with FECD are described below and in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Genes with Altered Expression in Endothelial Disease

| Gene | Cytogenetic Location | Protein | Function | Associated Phenotype(s) | Select References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFBI | 5q31.1 | Transforming growth factor-β-induced protein | Extracellular matrix protein | FECD Bullous keratopathy |

Elhalis et al., 2010 Jurkunas et al., 2009 Jurkunas et al., 2008a Kuot et al., 2012 Akhtar et al. 2001 |

| CLU | 8p21.1 | Clusterin | Protein chaperone Cell aggregation Cell apoptosis |

FECD | Jurkunas et al., 2008a Matthaei et al., 2019 Kuot et al., 2012 Jurkunas et al., 2009 |

| SNAI1 | 20q13.13 | Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition | FECD Fibrous downgrowth |

Okamura et al., 2015 Lee et al., 2018 |

| SNAI2 | 8q11.21 | Snail family transcriptional repressor 2 | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition | Fibrous downgrowth | Lee et al., 2018 |

| ZEB1 | 10p11.22 | Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 domain (or TCF8) | DNA binding transcription factor activity Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

FECD Fibrous downgrowth |

Okamura et al., 2015 Lee et al., 2018 |

| ZEB2 | 2q22.3 | Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2 domain | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition | Fibrous downgrowth | Lee et al., 2018 |

| FGF2 | 4q28.1 | Fibroblastic growth factor 2 | Cell migration Cell proliferation Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

Fibrous downgrowth |

Lee and Kay, 2012 Lee et al., 2012 Lee et al., 2018 Lee et al., 2019 |

FECD = Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy

Collagen type VIII alpha 2 chain (COL8A2)

In 1979, Magovern et al described a family with early onset FECD with autosomal dominance.(Magovern et al., 1979) Examination of this family showed unique small, round guttae located centrally, rather than larger guttae typical of FECD. Family members as young as age three exhibited findings. Further genetic analysis revealed a unique leucine450 to tryptophan amino acid substitution (L450W) in COL8A2.(Gottsch et al., 2005a) Similarly, an earlier study by Biswas et al revealed a Glutamine455 to Lysine (Q455K) missense point mutation in COL8A2 in a family with severe FECD in their 30s and 40s.(Biswas et al., 2001) Interestingly, both Gottsch et al and Biswas et al found subjects with these respective mutations who were diagnosed with posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy. Lastly, Mok et al identified an additional glutamine455 to valine (Q455V) missense mutation in Korean families with early onset FECD.(Mok et al., 2009)

Collagen VIII is a short chain collagen and is the major component of DM.(Sawada et al., 1990; Shuttleworth, 1997) The protein contains homo- and hetero-trimers of α1(VIII) and α2(VIII) chains.(Illidge et al., 2001; Illidge et al., 1998) In Descemet’s membrane, the protein forms layers of hexagonal lattices.(Sawada et al., 1990) Two different mouse models with Col8a2 mutations recapitulate some of the endothelial cells and DM findings of humans with early onset FECD.(Jun et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2013) Studies of these models suggest that L450W and Q455K mutations cause FECD via different avenues. The L450W mutation is associated with an accumulation of abnormally assembled type VIII collagen in DM with an anterior banded layer three times thicker than the normal.(Gottsch et al., 2005b; Zhang et al., 2006) This is accompanied by loss of endothelial cells and additional laminin and fibronectin deposition in the posterior non-banded layer.(Zhang et al., 2006) This supports the hypothesis that FECD is the result of abnormal basement membrane assembly rather than abnormal endothelial metabolism. Alternatively, the Q455K mutation causes progressive variability in endothelial cell size and shape, and formation of basement membrane guttae, but DM is of normal thickness.(Jun et al., 2012) Further examination of endothelial cells in both L450W and Q455K mutations demonstrate dilated endoplasmic reticulum and elevated markers of the unfolded protein response (UPR), supporting the idea that FECD is driven by cell apoptosis through the UPR pathway.(Jun et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2013) Additionally, mutations in COL8A2 may contribute to the altered biomechanical strength of the cornea. Homozygous Q455K and L450W knock-in mice demonstrate formation of a softer DM which precedes endothelial cells loss.(Leonard et al., 2019) Altered protein collagen structure could be preventing normal formation of a tight anterior banded layer and thus a softer DM, similar to what is observed in FECD patients.(Xia et al., 2016) Thus far, early-onset FECD has been linked to only COL8A2 and the evidence strongly supports the many ways altered collagen chains impact structure and function in early-onset FECD.

Transcription factor 4 (TCF4)

Based on a genome-wide association study, TCF4 variants are considered the most common cause of late-onset FECD in Caucasians of European descent and the presence of two variant copies increases the odds of having FECD by 30-fold.(Baratz et al., 2010; Matthaei et al., 2019) TCF4 encodes the E2–2 protein which is part of the class I basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors.(Murre et al., 1994) Wieben et al identified an intron CTG trinucleotide expansion repeat (TNR) where a repeat length greater than 50 was highly specific for FECD in a Caucasian cohort.(Wieben et al., 2012) Additionally, four small nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in TCF4 were found in association with FECD: rs613872, rs17595731, rs9954153, rs2286812.(Baratz et al., 2010) Both TCF4 TNR expansion and SNP have been noted in African American and Asian populations with FECD but with less prevalence, suggesting that these alterations pertain mostly to European Caucasians.(Matthaei et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019) Several mechanisms by which TCF4 affects the corneal endothelium have been proposed. Longer TNR expansions may be correlated with TCF4 upregulation.(Okumura et al., 2019) TCF4 has been shown to drive EnT in kidney and neuroblastoma tissue and may also act on corneal endothelial cells via interaction with TGF-β in the endoplasmic reticulum.(Okumura et al., 2019) Alternatively, TCF4 TNR expansion has been found to create RNA-mediated cell toxicity (Mootha et al., 2015) and RNA missplicing of genes encoding proteins involved in cytoskeletal protein binding and cell adhesion.(Du et al., 2015; Mootha et al., 2015; Wieben et al., 2017) Thus, TCF4 may play multiple roles in the etiology of endothelial dysfunction and FECD. Studies are investigating using anti-sense oligonucleotide therapy to target abnormal RNA as a possible treatment.(Hu et al., 2018; Zarouchlioti et al., 2018)

Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1)/ Transcription factor 8 (TCF8)

Missense mutations in the zinc finger Ebox binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) gene is associated with FECD in small groups of patients.(Zhang et al., 2019) ZEB1 employs two zinc finger domains which provide DNA-binding specificity. It is a transcriptional repressor which causes downstream promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition.(Vandewalle et al., 2009) It is also suppresses expression of collagen I (Terraz et al., 2001) and is up-regulated by TCF4.(Vedana et al., 2016) Missense mutations of ZEB1 have been observed in patients with late-onset FECD (Riazuddin et al., 2010b; Zhang et al., 2019) and is thought to cause protein loss of function.(Riazuddin et al., 2010b) ZEB1 has also been implicated in PPCD/PPMD, which is described later in section 2.2.

Solute carrier family 4 member 11 (SLC4A11)

Currently there are over 60 SLC4A11 missense mutations, in addition to other types of mutations, identified in relation to late-onset FECD and CHED.(Li et al., 2019) Most of these mutations cause protein misfolding, impaired protein localization in the cell membrane, impaired membrane transport function, and decreased cell proliferation.(Alka and Casey, 2018; Riazuddin et al., 2010a) A few mutations have been found to cause impaired cell adhesion to the DM.(Malhotra et al., 2019a) Also, SLC4A11 is known to participate in transmembrane water movement (Vilas et al., 2013) and transport of ions Na+, OH−, H+, NH3 and therefore may play a role in the corneal endothelial pump function.(Loganathan et al., 2016; Malhotra et al., 2019b) It may also affect antioxidant gene expression.(Guha et al., 2017) The role of SLC4A11 in CHED is further discussed in section 2.3.

Lipoxygenase homology domain-containing protein 1 (LOXHD1)

Investigation of a mutigenerational pedigree with autosomal dominant FECD revealed a missense mutation, R547C, within LOXHD1.(Riazuddin et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2019) Further examinations have yielded 15 more heterozygous missense mutations located to the folded protein surface which cause protein aggregation in the endothelium and DM.(Riazuddin et al., 2012) These findings suggest that mutation in LOXHD1 may cause impaired protein-protein interactions or cytotoxicity.(Riazuddin et al., 2012) Also of note, mutations in LOXHD1 have been associated with progressive hearing loss, but patients with this disease do not have FECD, suggesting a different genotypic or variable phenotypic expression.(Bai et al., 2020; Riazuddin et al., 2012; Wesdorp et al., 2018)

ATP/GTP-binding-like 1 (AGBL1)

In the corneal endothelium, AGBL1 encodes a glutamate decarboxylase. A nonsense mutation causing early protein termination as well as a heterozygous missense variant have been linked to late-onset FECD.(Riazuddin et al., 2013) AGBL1 may induce FECD via interaction with TCF4.(Riazuddin et al., 2013)

Transforming Growth Factor-β-induced protein (TGFBIP)

This extracellular matrix protein assists in cell adhesion and interacts with matrix components in the stroma and DM.(Elhalis et al., 2010). In FECD endothelium, TGFBIP is overexpressed (Jurkunas et al., 2008) and thickening of DM has been correlated with accumulation of TGFBIP.(Jurkunas et al., 2009) TGFBIP has also been shown to regulate TCF4 and ZEB1, which further supports EnT as a mechanism for FECD.(Kuot et al., 2012)

Clusterin (CLU)

In FECD, clusterin is overexpressed in endothelial cells but is limited to the anterior/stroma interface of DM as opposed to an even distribution in the DM of normal corneas.(Kuot et al., 2012) Additionally, endothelial cells exhibit enhanced CLU staining at the cell membrane borders next to guttae.(Jurkunas et al., 2008) Thus, it has been proposed that cell aggregation by CLU and cell adhesion by TGFBIP may be disrupted to form guttae.(Jurkunas et al., 2009) CLU mutations might also be associated with FECD.(Kuot et al., 2012)

FECD Loci

Genotyping of pedigrees with late-onset FECD has revealed four loci: FCD1 (chromosome 13, short arm, 13pTel-13q12.13) (Sundin et al., 2006b), FCD2 (chromosome 18, long arm, 18q21.2-q21.32) (Sundin et al., 2006a), FCD3 (chromosome 5, long arm, 5q33.1-q35.2) (Riazuddin et al., 2009) and FCD4 (chromosome 9, short arm, 9p22.1-p24.1) (Riazuddin et al., 2010b). Additional loci in chromosomes 1, 7, 15, 17, and X have been identified.(Afshari et al., 2009)

DNA repair enzymes

Polymorphisms within DNA repair enzymes have been implicated in FECD: RAD51 recombinase (RAD51) (Synowiec et al., 2013), Flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1) (Wojcik et al., 2014), X-ray repair cross complementary group (XRCC1) (Wójcik et al., 2015), Nei endonuclease VIII-like 1 (NEIL1) (Wójcik et al., 2015), DNA Ligase 3 (LIG3) (Synowiec et al., 2015). Alterations in these genes with subsequent deficiencies in DNA repair may cause the endothelium to be more susceptible to oxidative DNA damage and FECD formation.(Wójcik et al., 2015)

2.2. Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy (PPCD/PPMD)

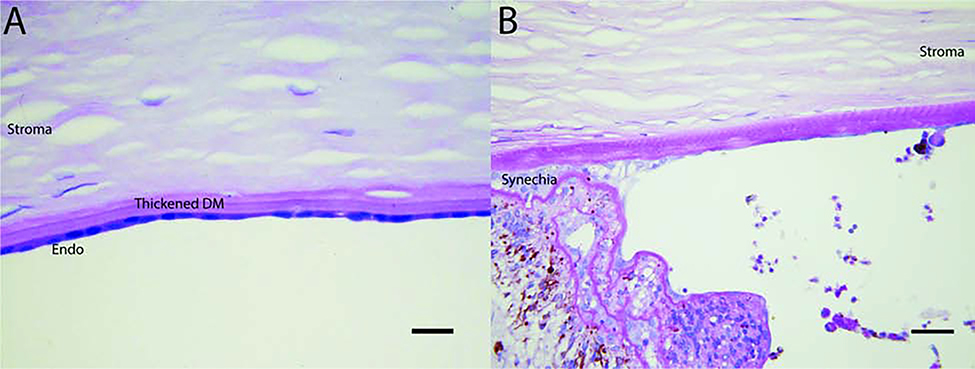

Also known as Schlichting dystrophy, PPCD is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by epithelial-like endothelial cells and a thickened, multilaminar posterior non-banded portion of DM (Fig. 2A).(Weiss et al., 2015) Clinically, patients may demonstrate clustered vesicles, gray-white plaques, or broad bands with serrated edges on the endothelium. Treatment of PPCD is similar to that of FECD. Endothelial keratoplasty is useful in progressive disease.

Figure 2.

A) Posterior polymorphous dystrophy with dense collection of endothelial cells resting on DM of increased thickness. No evidence of stratification is seen in this section (Periodic acid-Schiff stain [PAS]; bar = 15 microns). B) Iridocorneal endothelial syndrome of the Cogan-Reese type with pseudo-angle covered by basement membrane which extends on to iris surface where it becomes multilayered and entwined with a nodule of melanocytes (PAS; bar = 15 microns).

The previously identified autosomal dominant inherited disorder congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy type I (CHED1) is now considered PPCD after review of clinical and histopathologic findings.(Aldave et al., 2013; Weiss et al., 2015) Multiple loci have been identified in association with PPCD as described below and in Table 2. The majority are known to participate in transition of endothelial cells to an epithelium phenotype.

PPCD1 locus - Ovo like zinc finger 2 (OVOL2)

Four mutations in the promoter sequence of OVOL2 have been identified in PPCD.(Davidson et al., 2016) OVOL2 is a C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factor involved in mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and is a direct transcriptional repressor of ZEB1, which also has been implicated in PPCD.(Davidson et al., 2016) The role of OVOL2 in PPCD requires further investigation but it is likely that these mutations cause OVOL2 overexpression leading to ZEB1 suppression and expression of epithelial-like features in endothelial cells with loss of endothelial function.(Chung et al., 2017; Chung et al., 2019; Davidson et al., 2016)

PPCD2 locus - Collagen type VIII alpha 2 (COL8A2)

Examination of two patients with PPCD from the same family revealed a Q455K missense mutation in COL8A2.(Biswas et al., 2001) This mutation may be a rare polymorphism of PPCD since subsequent studies of other families with PPCD have failed to find the same mutation.(Aldave et al., 2013; Kobayashi et al., 2004; Yellore et al., 2005)

PPCD3 locus - Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox (ZEB1)

Multiple mutations in ZEB1 have been associated with PPCD.(Aldave et al., 2007) ZEB1 plays a role in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and has mutual feedback loops with PPCD loci OVOL2 and GRHL2, both of which support mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition.(Chung et al., 2019; Frausto et al., 2019) Therefore an altered balance between the three loci may alter corneal endothelial cell characteristics.(Chung et al., 2019) As noted earlier, ZEB1 mutations are also present in FECD. More of the ZEB1 mutations associated with PPCD are nonsense mutations whereas mutations causing FECD are missense mutations.(Riazuddin et al., 2010b) Thus, PPMD and FECD may differ in disease onset and severity due to a difference in haploinsufficiency versus protein dysfunction.(Riazuddin et al., 2010b)

PPCD4 locus - Grainyhead like transcription factor (GRHL2)

Mutation within the intronic region of the GRHL2 gene has also been correlated with PPCD.(Liskova et al., 2018) Like OVOL2, GRHL2 plays a role in mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and is a direct transcriptional repressor of ZEB1.(Liskova et al., 2018)

2.3. Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy (CHED), formerly known as CHED2, is an autosomal recessive dystrophy. Similar to FECD and PPMD, CHED exhibits a thickened, laminated DM and degenerated endothelial cells.(Weiss et al., 2015) Patients present in infancy with bilateral corneal clouding, and nystagmus.(Weiss et al., 2015) In rare instances band keratopathy and congenital glaucoma are present.(Weiss et al., 2015) Corneal transplant is frequently needed given age of presentation and risk for amblyopia.

Unlike FECD and PPMD which have been associated with multiple genes, CHED has been linked primarily to mutations in SLC4A11.(Hand et al., 1999; Jiao et al., 2007; Vithana et al., 2006) While SLC4A11 mutations associated with FECD usually result in dominant transmission, mutations in CHED appear recessive because of protein loss of function from both alleles.(Jiao et al., 2007; Vithana et al., 2006; Vithana et al., 2007) Most CHED-related mutations cause protein folding defects and poor cell surface proteins trafficking whereas FECD-related mutations do not impair trafficking and thus may have more functional impairments.(Alka and Casey, 2018) This holds true when observing SLC4A11 mutations that cause poor DM adhesion in CHED and FECD. CHED-related mutation fail to produce cell surface proteins to participate in adhesion whereas FECD-related mutations have impaired DM binding sites.(Malhotra et al., 2019a)

Mutations in CHED are related to dysregulation of neural crest cell function during endothelial development and premature endothelial cell death.(Jiao et al., 2007; Vithana et al., 2006) More specifically, SLC4A11 has been localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane and acts to suppress reactive oxidative species formation.(Ogando et al., 2019) Slc4a11−/− mice, mimicking features of CHED, demonstrate increased reactive oxidative species and cell apoptosis.(Ogando et al., 2019) Endothelial oxidative damage is also seen in FECD. Further investigation of SLC4A11 in FECD mitochondria may elucidate differences in oxidative stress and gene expression between the two dystrophies.

Harboyan Syndrome is a rare disorder consisting of CHED and sensorineural hearing loss that develops between age 10 and 15.(Siddiqui et al., 2014) The syndrome is due to a recessive mutation in SLC4A11 and the ocular manifestation is considered indistinguishable from CHED.(Siddiqui et al., 2014) It possible that Harboyan Syndrome is a progression of CHED with variable phenotype expressivity and thus all CHED patients should be assessed for hearing loss.(Siddiqui et al., 2014)

3. Post-operative Bullous Keratopathy

Bullous keratopathy describes a condition where corneal stromal edema develops as a result of trauma-related endothelial cell loss. Depending on the severity of endothelial cell loss, the cornea may progress from mild edema to a more severe stage with permanent stromal fibrosis, and epithelial bullae. Aphakic or pseudophakic bullous keratopathy is defined as bullous keratopathy from cataract surgery and is the most common cause of secondary corneal edema.(Siu et al., 2014) Intraoperative endothelial damage results from trauma by cataract particles, intracameral fluid turbulence, heat generation, and fluctuations in intraocular pressure.(Hayashi et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1997; Suzuki et al., 2014; Takahashi, 2016) Bullous keratopathy may also be seen in other surgical procedures such as trabeculectomy, tube shunt, and secondary intraocular lens placement.(Gonçalves et al., 2008)

Bullous keratopathy presents with significant alterations in the expression of different matrix components of DM and posterior stroma. Ljubimov et al studied 27 matrix components in twenty corneas with bullous keratopathy by immunofluorescence microscopy.(Ljubimov et al., 1996) They found a posterior collagenous layer in 80% of eyes, located on DM and in the remaining endothelial cells. This posterior collagenous layer, also called retrocorneal membrane, contained collagens I, III, IV, V, VI, VIII, XII, and XIV collagen, tenascin, fibronectin, decorin, perlecan, some laminin-1 and entactin-nidogen. Akhtar et al studied the expression of TGFBIP, tenascin-C, fibrillin, and fibronectin in pseudophakic bullous corneas and concluded that bullous keratopathy can be regarded as a response to injury followed by healing, which is characterized by scar formation, i.e. fibrosis.(Akhtar et al., 2001) Upregulation of these matrix proteins differs from that of FECD.(Weller et al., 2014) By studying the genes expressed after surgical removal of DM/endothelial cells complex, Weller et al. found that collagens I, III, and XVI, TGFBIP, agrin, fibronectin, clusterin, and integrin α4, were only upregulated in FECD. In contrast, collagens IV, V, VI, and versican showed a nonspecific upregulation in both FECD and pseudophakic bullous keratopathy.(Weller et al., 2014)

Like FECD, oxidative stress also plays a role in bullous keratopathy. It is thought that phacoemulsification ultrasound causes breakdown of water molecules and the formation of free radicals which may damage endothelial cells.(Takahashi, 2005) Oxidative stress may also cause disease progression in bullous keratopathy but via different oxidative pathways from FECD. Bullous keratopathy specimens demonstrate greater amounts of lipid peroxidation byproducts whereas FECD specimens had more nitrous oxide byproducts.(Buddi et al., 2002) Unlike FECD which exhibits endothelial cell death from oxidative DNA damage, bullous keratopathy tissue does not demonstrate markers of oxidative DNA damage.(Jurkunas et al., 2010) The discrepancies in fibrotic response and oxidative stress pathways seen in patients with pseudophakic bullous keratopathy and FECD warrant further research and suggest significant difference in the stress response by endothelial cells in these two conditions.

4. Metaplastic Endotheliopathies

These conditions are characterized by transformation of endothelial cells to a mesenchymal or epithelial-like phenotype and function. These transformed cells can deposit extracellular matrix or stratify and lose the inherent endothelial cell capacity to maintain stromal deturgescence (see Table 1).

4.1. Iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome

Iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome is a sporadic unilateral condition occurring more commonly in women. It includes 3 clinical variants with different clinical manifestations: Chandler syndrome, progressive iris atrophy, and Cogan-Reese syndrome.(Silva et al., 2018) Abnormal endothelium proliferates and migrates over the trabecular meshwork and iris, a unifying feature called endothelization (Fig. 2B). This abnormal proliferation of dysfunctional endothelial cells and endothelization of the anterior chamber causes corneal edema and the formation of peripheral anterior synechiae, changes in the appearance of the iris, abnormal pupil configuration, and glaucoma.(Silva et al., 2018)

The cause of ICE syndrome is unknown. Herpes simplex and Epstein-Barr viruses have been found in ICE tissue, suggesting a viral trigger in endothelial cell proliferation, but these findings need to be confirmed.(Alvarado et al., 1994; Groh et al., 1999; Tsai et al., 1990) Other studies have demonstrated epithelial-like qualities of the endothelium. Hirst et al using electron microscopy showed that cells present over DM in a case of Chandler syndrome had epithelium features including desmosomes, intracytoplasmic filaments, and microvillous surface projections. Immunohistochemistry characterization showed expression of epithelial keratins.(Hirst et al., 1983) By using an antibody specific for epithelial cell glycoproteins called 2B4.14.1, as well as vimentin and cytokeratin immuno-characterization in keratoplasty specimens, Howell et al showed that ICE cells come from an endothelial lineage that has epithelial features.(Howell et al., 1997). It has been proposed that these endothelial cells exhibit altered cyclin regulation, thus allowing the cells to overcome a normally non-replicative state.(Robert et al., 2013) On the other hand, there is some evidence to suggest that ICE is of epithelial origin. Levy et al., demonstrated that ICE cells expressed a profile of differentiation markers that resembles that of normal limbal epithelial cells suggesting that ICE syndrome may result from ectopic embryonic ocular surface epithelium. The findings could be explained as endothelial metaplasia, but in contrast to Howell et al, their immunologic characterization of ICE was negative for vimentin, which supports an epithelial cell origin.(Levy et al., 1995) Nevertheless, the evidence shows that epithelial-like changes are a consistent feature of ICE syndrome.

4.2. Post-traumatic or Post-surgical Fibrotic Changes of the Endothelium

Proliferation and deposition of fibrous tissue at the endothelium/DM complex is a rare but nonetheless serious complication of trauma or intraocular surgery. The incidence of epithelial or fibrous downgrowth has decreased in the last decades with less invasive surgical techniques and better wound closure following ocular trauma. However, retrocorneal membranes still occur after penetrating trauma, penetrating keratoplasty, endothelial transplantation, and are of relatively common occurrence after keratoprosthesis and glaucoma shunt implantation surgeries.

The cell origin of this fibrotic tissue is unknown. Immunohistological characterization of human retrocorneal membranes show fibrotic tissue posterior to DM and characterization of the cells embedded in the fibrotic tissue show the following patterns: (1) the most common, stromal downgrowth membranes, are strongly positive for alpha smooth muscle actin and vimentin, and negative for all types of keratins; (2) metaplastic fibrous endothelial membranes are cytokeratin positive, vimentin positive, and mildly to moderately alpha smooth muscle actin positive; and (3) membranes of epithelial downgrowth are strongly positive for keratins, alpha smooth muscle actin and vimentin negative.(Jakobiec and Bhat, 2010)

Additional studies have shown evidence of endothelial-mesenchymal transition of cells and deposition of collagen products within post-traumatic retrocorneal membranes. Interleukin 1 is believed to upregulate fibroblastic growth factor (FGF2) in endothelial cells during inflammation and trigger EnT.(Lee and Kay, 2012; Lee et al., 2012) In in vitro and ex vivo models, human endothelial cells challenged with FGF2 stimulation undergo EnT with changes in cell shape and expression of mesenchymal transition marker genes: snail family transcriptional repressor 1 and 2 (SNAI1 and SNAI2) and zinc finger E-box–binding homeobox 1 and 2 (ZEB1 and ZEB2). This EnT phenotype transition is followed by the expression of fibronectin, vimentin, and type I collagen.(Lee et al., 2018) Similarly, siRNA knockdown of FGF2 in vivo mouse model abolished the formation of traumatic retrocorneal membranes.(Lee et al., 2019)

In summary, the cell origin and mechanism of post-traumatic retrocorneal membrane formation are not entirely clear. Various cell types may be involved and it is possible that the cell source depends on the mode of injury. Fibrous endothelial metaplasia has been observed and may result from the transformation of mature, post-mitotic endothelial cells into replicating fibroblasts. However, further evidence is required to fully explain how quiescent human endothelial cells, and arrested in the cell cycle, transition to fibroblasts.

While there is limited information on the mechanisms by which metaplastic endotheliopathies result in membranes, studies of endothelial dystrophies showing endothelial transition to either epithelial or fibroblastic phenotypes may be an applicable model. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition-inducing genes ZEB1 and SNAI1 are upregulated in cultured endothelial cells that produce excess extracellular matrix proteins.(Okumura et al., 2015) Frausto et al demonstrated that knocking-out ZEB1 in corneal endothelial cells favors epithelial transformation and postulate that endothelial cells reside in a hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal state consistent with its mixed gene expression profile.(Frausto et al., 2019) Better understanding of the cell phenotype transition could spawn pharmacological or gene therapies for multiple corneal endothelial diseases including FECD, PPMD and metaplastic endotheliopathies.

5. Corneal Endothelial Decompensation in Other Diseases

Many ocular and systemic diseases cause alterations and potential decompensation of the corneal endothelium. Two common ocular diseases, glaucoma and diabetic eye involvement compromise corneal endothelial function and are discussed in this section. While the mechanisms of endothelial damage are not entirely clear, the results from studies thus far can provide insight in how the endothelium responds to stress. Results are summarized in Table 1.

5.1. Glaucoma

Glaucoma and its treatments can damage the corneal endothelium. Examination of endothelial cell density in various glaucomatous diseases suggests that intraocular pressure accelerates endothelial cell loss.(Janson et al., 2018) The toxic effects of glaucoma medications is also thought to cause endothelial cell injury. However, while molecular studies have demonstrated decline in endothelial cell health, clinically there has been no significant changes observed to endothelial cells.(Janson et al., 2018). On the other hand, there is well-documented evidence that surgical glaucoma implants cause progressive endothelial cell damage.(Janson et al., 2018) This may to be due alterations in anterior chamber fluid dynamics, or direct irritation of the cells by the implants.(Janson et al., 2018) Alternatively, endothelial cell loss may be due to glaucomatous changes in the aqueous environment.(Janson et al., 2018)

5.2. Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus can present with endothelial damage and corneal edema similar to FECD.(Goldstein et al., 2020) Although there are some contradicting reports, studies have shown that endothelial cells in persons with diabetes have increased pleomorphism and polymegethism and a higher rate of endothelial cell death like FECD.(Goldstein et al., 2020) Others have shown that cell mitochondria exhibit swelling and metabolic dysfunction.(Goldstein et al., 2020) Decreased Na+/K+ ATPase pump function and poor tight-junction formation contribute to corneal thickening.(Goldstein et al., 2020) Information on extracellular matrix changes caused by diabetes mellitus in DM and corneal endothelial cells is limited. Electron microscopy of DM in diabetic corneal tissue demonstrates randomly distributed aggregates of wide-spaced collagen fibrils.(Rehany et al., 2000) FECD, PPMD, CHED and bullous keratopathy also display abnormally wide-spaced collagen but to a lesser degree.(Rehany et al., 2000) It is possible that abnormal spacing in diabetes is due to hyperglycemic glycosylation of normal collagen whereas in other endothelial diseases it is due to altered matrix expression.(Rehany et al., 2000) Additionally, severe changes in DM and the anterior chamber angle can occur with neovascularization. Additional effects of diabetes on endothelial structure have yet to be elucidated, but could provide a greater understanding of the effects of altered glucose metabolism on the cornea.

Summary

Corneal endothelial diseases represent different etiologies with a common final pathway: compromised corneal function caused by increased stromal and epithelial swelling with abnormal light scatter. This review summarizes the most common diseases that affect the endothelium. These diseases share similar characteristics such as thickened DM due to an abnormal extracellular matrix, or formation of membranes posterior to DM due to transformation of endothelial cells. Altered endothelial cell function and cell loss is another common theme. The multiple molecular mechanisms and genes associated with FECD suggests that the disease has multiple causal pathways. Some of the genes associated with FECD have been linked to other endothelial diseases such as PPCD and CHED. However, different mutations lead to different phenotypic expressions. We also discuss alterations in corneal endothelial function in glaucoma and diabetes mellitus, two diseases which feature endothelial changes similar to innate endothelial diseases. Further advances in gene analysis and molecular research have demonstrated the genetic complexity of these diseases and opened additional investigational avenues. Newer, more sophisticated and less invasive surgical techniques for endothelial cell conservation and replacement have improved the prognosis of these disorders. Medical interventions may soon emerge as basic science research provides a better understanding of the pathogenesis of corneal endothelial diseases.

Highlights.

Normal structure and function of endothelial cells is necessary for normal vision.

Different diseases with genetic and acquired etiologies affect endothelial function and compromise vision.

A better understanding of the biological processes regulating endothelial pathophysiology is needed for translational research.

Understanding the mechanisms regulating endothelial transformation and proliferation will help in the clinical management of proliferative endothelial diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NEI grant EY029395.

Footnotes

Proprietary Interests: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adamis AP, Filatov V, Tripathi BJ, Tripathi R.A.m.C., 1993. Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy of the cornea. Survey of Ophthalmology 38, 149–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshari NA, Li Y-J, Pericak-Vance MA, Gregory S, Klintworth GK, 2009. Genome-wide linkage scan in fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 50, 1093–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S, Bron AJ, Hawksworth NR, Bonshek RE, Meek KM, 2001. Ultrastructural morphology and expression of proteoglycans, betaig-h3, tenascin-C, fibrillin-1, and fibronectin in bullous keratopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 85, 720–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldave AJ, Han J, Frausto RF, 2013. Genetics of the corneal endothelial dystrophies: an evidence-based review. Clin Genet 84, 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldave AJ, Yellore VS, Yu F, Bourla N, Sonmez B, Salem AK, Rayner SA, Sampat KM, Krafchak CM, Richards JE, 2007. Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy is associated with TCF8 gene mutations and abdominal hernia. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 143A, 2549–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alka K, Casey JR, 2018. Molecular phenotype of SLC4A11 missense mutants: Setting the stage for personalized medicine in corneal dystrophies. Human Mutation 39, 676–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado JA, Underwood JL, Green WR, Wu S, Murphy CG, Hwang DG, Moore TE, O’Day D, 1994. Detection of herpes simplex viral DNA in the iridocorneal endothelial syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 112, 1601–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi B, Ziaei A, Fuchsluger T, Schmedt T, Chen Y, Jurkunas UV, 2011. p53-regulated increase in oxidative-stress--induced apoptosis in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: a native tissue model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, 9291–9297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Zhang C, Zhang F, Xiao Y, Jin Y, Wang H, Xu L, 2020. Five Novel Mutations in LOXHD1 Gene Were Identified to Cause Autosomal Recessive Nonsyndromic Hearing Loss in Four Chinese Families. Biomed Res Int 2020, 1685974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baratz KH, Tosakulwong N, Ryu E, Brown WL, Branham K, Chen W, Tran KD, Schmid-Kubista KE, Heckenlively JR, Swaroop A, Abecasis G, Bailey KR, Edwards AO, 2010. E2–2 protein and Fuchs’s corneal dystrophy. N Engl J Med 363, 1016–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Munier FL, Yardley J, Hart-Holden N, Perveen R, Cousin P, Sutphin JE, Noble B, Batterbury M, Kielty C, Hackett A, Bonshek R, Ridgway A, McLeod D, Sheffield VC, Stone EM, Schorderet DF, Black GC, 2001. Missense mutations in COL8A2, the gene encoding the alpha2 chain of type VIII collagen, cause two forms of corneal endothelial dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 10, 2415–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno JA, 2003. Identity and regulation of ion transport mechanisms in the corneal endothelium. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 22, 69–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borderie VM, Baudrimont M, Vallée A, Ereau TL, Gray F, Laroche L, 2000. Corneal endothelial cell apoptosis in patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41, 2501–2505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddi R, Lin B, Atilano SR, Zorapapel NC, Kenney MC, Brown DJ, 2002. Evidence of oxidative stress in human corneal diseases. J Histochem Cytochem 50, 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung DD, Frausto RF, Cervantes AE, Gee KM, Zakharevich M, Hanser EM, Stone EM, Heon E, Aldave AJ, 2017. Confirmation of the OVOL2 Promoter Mutation c.−307T>C in Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy 1. PLoS One 12, e0169215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung DD, Zhang W, Jatavallabhula K, Barrington A, Jung J, Aldave AJ, 2019. Alterations in GRHL2-OVOL2-ZEB1 axis and aberrant activation of Wnt signaling lead to altered gene transcription in posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy. Exp Eye Res 188, 107696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AE, Liskova P, Evans CJ, Dudakova L, Nosková L, Pontikos N, Hartmannová H, Hodaňová K, Stránecký V, Kozmík Z, Levis HJ, Idigo N, Sasai N, Maher GJ, Bellingham J, Veli N, Ebenezer ND, Cheetham ME, Daniels JT, Thaung CM, Jirsova K, Plagnol V, Filipec M, Kmoch S, Tuft SJ, Hardcastle AJ, 2016. Autosomal-Dominant Corneal Endothelial Dystrophies CHED1 and PPCD1 Are Allelic Disorders Caused by Non-coding Mutations in the Promoter of OVOL2. Am J Hum Genet 98, 75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira RC, Wilson SE, 2020. Descemet’s membrane development, structure, function and regeneration. Exp Eye Res 197, 108090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Aleff RA, Soragni E, Kalari K, Nie J, Tang X, Davila J, Kocher JP, Patel SV, Gottesfeld JM, Baratz KH, Wieben ED, 2015. RNA toxicity and missplicing in the common eye disease fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. J Biol Chem 290, 5979–5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBAA, 2020. 2019 Eye Banking Statistical Report. Eye Bank Association of America. https://restoresight.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2019-EBAA-Stat-Report-FINAL.pdf (accessed 12 January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Edelhauser HF, 2006. The balance between corneal transparency and edema: the Proctor Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47, 1754–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eghrari AO, Gottsch JD, 2010. Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 5, 147–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhalis H, Azizi B, Jurkunas UV, 2010. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Ocul Surf 8, 173–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler C, Kelliher C, Spitze AR, Speck CL, Eberhart CG, Jun AS, 2010a. Unfolded protein response in fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: a unifying pathogenic pathway? Am J Ophthalmol 149, 194–202.e192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler C, Kelliher C, Spitze AR, Speck CL, Eberhart CG, Jun AS, 2010b. Unfolded protein response in fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: a unifying pathogenic pathway? American journal of ophthalmology 149, 194–202.e192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana EM, Huang B, 2010. Confocal microscopy study of donor-recipient interface after Descemet’s stripping with endothelial keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 94, 903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frausto RF, Chung DD, Boere PM, Swamy VS, Duong HNV, Kao L, Azimov R, Zhang W, Carrigan L, Wong D, Morselli M, Zakharevich M, Hanser EM, Kassels AC, Kurtz I, Pellegrini M, Aldave AJ, 2019. ZEB1 insufficiency causes corneal endothelial cell state transition and altered cellular processing. PLoS One 14, e0218279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AS, Janson BJ, Skeie JM, Ling JJ, Greiner MA, 2020. The effects of diabetes mellitus on the corneal endothelium: A review. Surv Ophthalmol 65, 438–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves ED, Campos M, Paris F, Gomes JA, Farias CC, 2008. [Bullous keratopathy: etiopathogenesis and treatment]. Arq Bras Oftalmol 71, 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottsch JD, Sundin OH, Liu SH, Jun AS, Broman KW, Stark WJ, Vito EC, Narang AK, Thompson JM, Magovern M, 2005a. Inheritance of a novel COL8A2 mutation defines a distinct early-onset subtype of fuchs corneal dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46, 1934–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottsch JD, Zhang C, Sundin OH, Bell WR, Stark WJ, Green WR, 2005b. Fuchs corneal dystrophy: aberrant collagen distribution in an L450W mutant of the COL8A2 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46, 4504–4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh MJ, Seitz B, Schumacher S, Naumann GO, 1999. Detection of herpes simplex virus in aqueous humor in iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome. Cornea 18, 359–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha S, Chaurasia S, Ramachandran C, Roy S, 2017. SLC4A11 depletion impairs NRF2 mediated antioxidant signaling and increases reactive oxygen species in human corneal endothelial cells during oxidative stress. Sci Rep 7, 4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halilovic A, Schmedt T, Benischke AS, Hamill C, Chen Y, Santos JH, Jurkunas UV, 2016. Menadione-Induced DNA Damage Leads to Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Fragmentation During Rosette Formation in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Antioxid Redox Signal 24, 1072–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand CK, Harmon DL, Kennedy SM, FitzSimon JS, Collum LM, Parfrey NA, 1999. Localization of the gene for autosomal recessive congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED2) to chromosome 20 by homozygosity mapping. Genomics 61, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Hayashi H, Nakao F, Hayashi F, 1996. Risk factors for corneal endothelial injury during phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg 22, 1079–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa A, Sakai H, Sawaguchi S, Iwase A, Tomidokoro A, Amano S, Araie M, 2011. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Cornea Guttata in a Population-Based Study in a Southwestern Island of Japan: The Kumejima Study. Archives of Ophthalmology 129, 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst LW, Green WR, Luckenbach M, de la Cruz Z, Stark WJ, 1983. Epithelial characteristics of the endothelium in Chandler’s syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 24, 603–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell DN, Damms T, Burchette JL Jr., Green WR, 1997. Endothelial metaplasia in the iridocorneal endothelial syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38, 1896–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Rong Z, Gong X, Zhou Z, Sharma VK, Xing C, Watts JK, Corey DR, Mootha VV, 2018. Oligonucleotides targeting TCF4 triplet repeat expansion inhibit RNA foci and mis-splicing in Fuchs’ dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 27, 1015–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illidge C, Kielty C, Shuttleworth A, 2001. Type VIII collagen: heterotrimeric chain association. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 33, 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illidge C, Kielty CM, Shuttleworth CA, 1998. Stability of type VIII collagen homotrimers: comparison with alpha1(X). Biochem Soc Trans 26, S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobiec FA, Bhat P, 2010. Retrocorneal membranes: a comparative immunohistochemical analysis of keratocytic, endothelial, and epithelial origins. Am J Ophthalmol 150, 230–242 e232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalimarada SS, Ogando DG, Bonanno JA, 2014. Loss of ion transporters and increased unfolded protein response in Fuchs’ dystrophy. Mol Vis 20, 1668–1679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson BJ, Alward WL, Kwon YH, Bettis DI, Fingert JH, Provencher LM, Goins KM, Wagoner MD, Greiner MA, 2018. Glaucoma-associated corneal endothelial cell damage: A review. Surv Ophthalmol 63, 500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X, Sultana A, Garg P, Ramamurthy B, Vemuganti GK, Gangopadhyay N, Hejtmancik JF, Kannabiran C, 2007. Autosomal recessive corneal endothelial dystrophy (CHED2) is associated with mutations in SLC4A11. J Med Genet 44, 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce NC, Harris DL, Mello DM, 2002. Mechanisms of mitotic inhibition in corneal endothelium: contact inhibition and TGF-beta2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43, 2152–2159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun AS, 2010. One hundred years of Fuchs’ dystrophy. Ophthalmology 117, 859–860 e814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun AS, Meng H, Ramanan N, Matthaei M, Chakravarti S, Bonshek R, Black GC, Grebe R, Kimos M, 2012. An alpha 2 collagen VIII transgenic knock-in mouse model of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy shows early endothelial cell unfolded protein response and apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet 21, 384–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkunas UV, Bitar M, Rawe I, 2009. Colocalization of increased transforming growth factor-beta-induced protein (TGFBIp) and Clusterin in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50, 1129–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkunas UV, Bitar MS, Funaki T, Azizi B, 2010. Evidence of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Am J Pathol 177, 2278–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkunas UV, Bitar MS, Rawe I, Harris DL, Colby K, Joyce NC, 2008. Increased clusterin expression in Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49, 2946–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katikireddy KR, White TL, Miyajima T, Vasanth S, Raoof D, Chen Y, Price MO, Price FW, Jurkunas UV, 2018. NQO1 downregulation potentiates menadione-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition during rosette formation in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Free Radic Biol Med 116, 19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuc E, Bainer R, Wolf M, Clay SM, Weisenberger DJ, Kemmer J, Weaver VM, Hwang DG, Chan MF, 2017. Comprehensive characterization of DNA methylation changes in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. PLoS One 12, e0175112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EC, Meng H, Jun AS, 2013. Lithium treatment increases endothelial cell survival and autophagy in a mouse model of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. The British journal of ophthalmology 97, 1068–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EC, Meng H, Jun AS, 2014. N-Acetylcysteine increases corneal endothelial cell survival in a mouse model of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Experimental Eye Research 127, 20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EK, Cristol SM, Geroski DH, McCarey BE, Edelhauser HF, 1997. Corneal Endothelial Damage by Air Bubbles During Phacoemulsification. Archives of Ophthalmology 115, 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa K, Kojima M, Sasaki H, Shui YB, Chew SJ, Cheng HM, Ono M, Morikawa Y, Sasaki K, 2002. Prevalence of primary cornea guttata and morphology of corneal endothelium in aging Japanese and Singaporean subjects. Ophthalmic Res 34, 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klyce SD, 2020. 12. Endothelial pump and barrier function. Exp Eye Res 198, 108068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Fujiki K, Murakami A, Kato T, Chen L-Z, Onoe H, Nakayasu K, Sakurai M, Takahashi M, Sugiyama K, Kanai A, 2004. Analysis of COL8A2 Gene Mutation in Japanese Patients with Fuchs’ Endothelial Dystrophy and Posterior Polymorphous Dystrophy. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology 48, 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krachmer JH, Purcell JJ Jr, Young CW, Bucher KD, 1978. Corneal Endothelial Dystrophy: A Study of 64 Families. Archives of Ophthalmology 96, 2036–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuot A, Hewitt AW, Griggs K, Klebe S, Mills R, Jhanji V, Craig JE, Sharma S, Burdon KP, 2012. Association of TCF4 and CLU polymorphisms with Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy and implication of CLU and TGFBI proteins in the disease process. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 632–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laule A, Cable MK, Hoffman CE, Hanna C, 1978. Endothelial cell population changes of human cornea during life. Arch Ophthalmol 96, 2031–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Jung E, Heur M, 2019. Injury induces endothelial to mesenchymal transition in the mouse corneal endothelium in vivo via FGF2. Mol Vis 25, 22–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JG, Jung E, Heur M, 2018. Fibroblast growth factor 2 induces proliferation and fibrosis via SNAI1-mediated activation of CDK2 and ZEB1 in corneal endothelium. J Biol Chem 293, 3758–3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JG, Kay EP, 2012. NF-kappaB is the transcription factor for FGF-2 that causes endothelial mesenchymal transformation in cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, 1530–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JG, Ko MK, Kay EP, 2012. Endothelial mesenchymal transformation mediated by IL-1beta-induced FGF-2 in corneal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res 95, 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard BC, Jalilian I, Raghunathan VK, Wang W, Jun AS, Murphy CJ, Thomasy SM, 2019. Biomechanical changes to Descemet’s membrane precede endothelial cell loss in an early-onset murine model of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Exp Eye Res 180, 18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SG, McCartney AC, Baghai MH, Barrett MC, Moss J, 1995. Pathology of the iridocorneal-endothelial syndrome. The ICE-cell. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36, 2592–2601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QJ, Ashraf MF, Shen DF, Green WR, Stark WJ, Chan CC, O’Brien TP, 2001. The role of apoptosis in the pathogenesis of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy of the cornea. Arch Ophthalmol 119, 1597–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Hundal KS, Chen X, Choi M, Ogando DG, Obukhov AG, Bonanno JA, 2019. R125H, W240S, C386R, and V507I SLC4A11 mutations associated with corneal endothelial dystrophy affect the transporter function but not trafficking in PS120 cells. Exp Eye Res 180, 86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]