Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex and heterogeneous systemic autoimmune disease associated with innate and adaptive immune dysregulation. SLE occurs primarily in females of childbearing age, with increased prevalence and severity in minority populations. Despite improvements in treatment modalities, SLE patients frequently experience periods of heightened disease activity and flare that can lead to permanent organ damage, increased morbidity, and early mortality. Such outcomes impair quality of life and inflict a significant socioeconomic burden. Predicting changes in SLE disease activity could allow for closer monitoring and preemptive treatment, but existing clinical, demographic and serologic markers have been only modestly predictive. Novel, proactive approaches to clinical disease management are thus critically needed. Panels of blood biomarkers can detect a breadth of immune pathway dysregulation that captures SLE heterogeneity and disease activity. Alterations in the balance of pro-inflammatory and regulatory soluble mediators have been associated with changes in clinical disease activity and are detectable several weeks prior to clinical flare occurrence. A soluble mediator score has been highly predictive of impending flare in both European American and African American SLE patients, and this score does not require a priori knowledge of specific pathway activation in the patient. We review current concepts of disease activity and flare in SLE, focusing on the potential of novel blood biomarkers to characterize and predict changes in disease activity. Measuring the disordered immune response in SLE in this way promises to improve disease management and prevent organ damage in SLE.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Clinical Disease Flare, Clinical Disease Activity, Cytokines, Biomarkers, Forecasting

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, heterogeneous autoimmune disease associated with complex and varied immune dysregulation [1, 2]. SLE clinically involves multiple organ systems, including the musculoskeletal, mucocutaneous, cardiopulmonary, renal and hematologic systems [3–5]. Clinical sequelae are preceded by immune system pathway activation and an accumulation of pathogenic autoantibody specificities, indicating breaks in immune tolerance and a feed-forward path of disease pathogenesis [6–8]. Although 20–30% of SLE patients experience chronically active or quiescent disease, most SLE patients have a waxing and waning disease course, with periods of active clinical disease and flare interspersed with intervals of low clinical disease activity [9, 10].

Disease exacerbations or flares in SLE span in range of severity from mild or moderate episodes that can be managed in the clinic to life threatening flares that require hospitalization. These flares place patients at risk for permanent organ damage [11, 12], are associated with significant morbidity [13], and contribute to increased healthcare costs [14, 15]. Limiting the frequency and severity of flares has been an ongoing objective in SLE disease management, with extensive research focused on assessment of imminent flare risk and development of flare prediction biomarkers [16]. In this review we summarize current clinical practice regarding SLE clinical disease activity and flare assessment and review recent findings of immunologic changes in SLE in relation to changes in disease activity and flare.

2. Clinical disease activity assessment in SLE

Of the disease activity measures proposed in observational studies and clinical trials to date [17], the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) with modifications [18–20], the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Index 2004 (BILAG 2004) [21], and Safety of Estrogens in Lupus National Assessment (SELENA)-SLEDAI physician global assessment (SSPGA) [19] remain widely utilized. Beyond their individual strengths and weaknesses (reviewed elsewhere [22]), SLEDAI and BILAG were both developed through a consensus approach to derive thresholds for changes in disease activity (Table 1). The SLEDAI provides a global index of 24 weighted clinical and laboratory variables reflecting disease activity in the preceding 30 days [18]. The SELENA-SLEDAI modification was developed to allow scoring of persistently active disease in some descriptors [19]. In addition, SLEDAI-2K includes modifications of the original SLEDAI in proteinuria scoring [20]. Contrasting the SLEDAI, the BILAG global index scores disease activity on an ordinal scale (A to E) across 8 organ domains while being anchored on the physician’s intention to treat [23]. Disease activity is assessed over a month and must be compared to preceding month’s scores, with same, worsening or improving clinical manifestations defined by an extensive glossary. The widely used and validated BILAG-2004 index was derived after modifications [21, 24] to include a weighted numerical conversion that allows additive global scoring across BILAG domains for clinical trials [25, 26]. As opposed to indices with predefined cut offs in disease activity, visual analogue scales (VAS) allow continuous scaling based on clinical observation. The SSPGA was developed as a 3 inch VAS and later adapted to a 100 mm scale, with anchors at mild, moderate and severe disease [19]. Each of these scoring systems correlate with each other reasonably well, and SSPGA changes were shown to be consistent with directional changes in BILAG and SLEDAI [27, 28].

Table 1.

Validated Instruments to Assess Clinical Disease Activity in SLE

| SLEDAI | BILAG | PGA |

|---|---|---|

| Global index of 24 weighted variables* |

|

|

| Modifications include SELENA-SLEDAI, SLEDAI-2K | BILAG 2004 modifications (9 domains**, glossary modifications) | Normalized to 100mm VAS in clinical trials |

| Summed to total score 0–105 | Modifications allow summation of domain scores | |

| Activity in preceding 30 days | Activity in the preceding 4 weeks | Activity in the preceding month |

| Each 30-day period scored independently of previous disease activity | Transitional index: each manifestation must be compared to previous 4 weeks – absent, same, improving, worse or new | Each monthly period scored independently of previous disease activity |

| Extensively used and validated | Most comprehensive SLE disease activity instrument to date | Simple and intuitive |

| Limitations: | ||

|

|

|

seizures, psychosis, organic brain syndrome, visual disturbance, cranial nerve disorder, lupus headache, CVA, vasculitis, arthritis, myositis, urinary casts, hematuria, proteinuria, pyuria, rash, alopecia, mucosal ulcers, pleurisy, pericarditis, low complement, increased DNA binding, fever, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia

constitutional, mucocutaneous, neuropsychiatric, musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, ophthalmic, renal, hematologic

Disease activity instruments remain critical in lupus clinical research to facilitate the longitudinal evaluation of patients, provide a framework of meaningful comparisons between clinicians, and allow clinical study comparisons [22]. Such instruments may also have a role in routine clinical care of SLE patients as part of a treat to target approach in disease management [29]. Regular patient monitoring by at least one validated disease activity measure is advocated in routine lupus care, with the aim of attaining remission or low disease activity [30]. Applicability of SLEDAI and BILAG in routine lupus care is, however, hindered by complexity inherent to those instruments, coupled with limited familiarity of many clinicians, and increasingly enforced time constraints. Efforts to develop simple versatile disease assessment tools suitable for clinic use are ongoing [31, 32].

3. Definition, prevalence, and burden of clinical disease flare in SLE

Prompt and accurate SLE flare assessment is central in routine patient care and in lupus clinical trials, where time to first flare and the frequency and severity of flares are common major secondary endpoints. A consensus definition of flare was derived by an international collaborative effort under the auspices of the Lupus Foundation of America to align flare assessment within the global community of lupus clinicians and clinical researchers [33]. Flare was defined as “a measurable increase in disease activity involving new or worse clinical signs and symptoms and/or laboratory measurements. This must be considered clinically significant by the assessor with usually at least some consideration of a change or an increase in treatment.” SLE flares need to be distinguished from otherwise minor fluctuations in disease activity and from active, but clinically stable disease. Flares should also be differentiated from progressive organ damage, as well as a number of other pathologies, including infection, drug reaction, and fibromyalgia, which can mimic or coexist with a flare. Anchored in clinical acumen, a detailed history and exam, along with targeted laboratory testing, are cornerstones of lupus flare assessment, with a secondary role of serologic markers, including decreasing C3 and C4 complement levels, and increasing titers of autoantibodies to dsDNA [16].

Initially geared toward disease activity measurement, SLEDAI and BILAG were later adapted for flare assessment in lupus clinical research by examining changes between visits [34, 35] (Table 2). A ≥3 point increase in SELENA-SLEDAI was considered reflective of clinically significant worsening, with an increase to a total score >12 sufficing for severe flare [35]. A >3 point increase in SLEDAI-2K was similarly proposed to capture flare [36]. New or worsening organ domain scores are used in the BILAG 2004 flare index to define severe (one A score), moderate (≥2 B scores), or mild (one B or ≥3C scores) flares [37]. An increase in the SSPGA (3-point VAS) by ≥1 point from baseline was proposed to reflect mild/moderate worsening, and an increase to >2.5 a severe flare [35]. The SELENA-SLEDAI flare index (SSFI) was specifically developed for flare measurement, and remains widely utilized in clinical trials with modifications [19]. Based on the SELENA-SLEDAI, the SSFI rates flares as mild/moderate or severe by a combination of changes in SELENA-SLEDAI total score, new or worsening clinical features not otherwise captured by SELENA-SLEDAI, medication changes, and changes in the SSPGA [19]. The SSFI does not however differentiate mild from moderate flares, and could potentially score flares on the sole basis of treatment changes irrelevant to disease activity. It can also be problematic in patients with high disease activity at baseline when a severe flare is triggered by modest increases in the SELENA-SLEDAI to >12. Modifications to the SSFI to exclude pharmacology criteria or to necessitate increases in the total SELENA-SLEDAI score, in addition to clinical or pharmacologic criteria, have been proposed [38].

Table 2.

Instruments for Clinical Flare Assessment in SLE

| Mild/moderate flare | Severe flare | |

|---|---|---|

| SELENA-SLEDAI | ≥3-point increase (to ≤12) | Increase to >12 |

| BILAG 2004* | Mild: one B or ≥3 C domain scores Moderate: ≥2 B domain scores |

one A domain score |

| SSPGA | ≥1 -point increase (to ≤2.5) | Increase to >2.5 |

| SSFI (at least one of items listed) |

|

|

BILAG domain scores due to new or worse manifestations

manifestations requiring doubling of prednisone, prednisone increase to >0.5mg/kg/d or hospitalization

In the SLE patient population, the majority of clinical disease flares are mild to moderate, presenting with a variety of constitutional, musculoskeletal, hematologic, and mucocutaneous features. Severe flares occur 20–30% of the time, and are more often characterized by renal, cardiovascular, respiratory and/or significant hematologic manifestations [13]. In the prospective Hopkins Lupus Cohort, flare rates in SLE patients on standard of care treatment ranged from 0.25 (BILAG A) to 1.77 (BILAG A or B) episodes per person-year [39]. In patients from the placebo arm of the combined phase III belimumab studies, rates of moderate to severe flare by different instruments ranged from 23.7 to 32% of SLE patients experiencing a clinical disease flare during a year of longitudinal follow-up [40]. Even when mild, lupus flares can significantly compromise quality of life and limit work productivity [15], whereas moderate and severe flares usually necessitate treatment with steroids and other immune suppressants that carry significant side effects, and can lead to hospitalization. Flares have been associated with damage accrual [11, 12], attributed to the inflammatory process itself, comorbidities (like depression and cardiovascular disease), and side effects of medications, particularly those related to corticosteroids. From a socioeconomic perspective, flares are linked to direct health-related expenses, as well as a number of indirect costs related to loss of productivity [14, 15].

4. SLE clinical flare prediction

Regular clinical monitoring is routine in SLE patients. It is nonetheless common for patients to seek medical attention outside routine follow up visits due to lupus flare, forcing clinicians to reactively treat patients. The increased risk of permanent organ damage and morbidity secondary to persistent disease activity and flare has led to great interest in development of tools for clinical disease flare prediction. The ability to predict clinical flares would alert clinicians and patients alike to potential flare precipitants, and could allow preemptive adjustment of immune suppressive medications to prevent clinical worsening. Alternatively, more frequent and accurate disease activity monitoring has the potential to allow clinicians to reduce the use of immune modulating treatments in select patients with clinically and immunologically stable disease [41]. Considering the emerging challenges of in-clinic monitoring due to COVID-19, disease activity and flare prediction biomarkers could play an even larger role in SLE patient management when in-person assessments cannot be performed.

Numerous clinical and epidemiologic studies have examined associations of clinical, serologic and immunologic characteristics with baseline flare risk in SLE with variable results, as reviewed elsewhere [16]. Rising titers of anti-dsDNA have been related to disease exacerbations, including renal flare, albeit with heterogeneous results, and are considered modestly predictive [42]. Cell bound complement activation products (CBCAPs) have shown some promise in flare prediction, with elevated C4d being most sensitive with regard to subsequent flare, and elevated Bb most specific. Yet, levels can be similar in many patients with inactive disease [43]. In the combined BLISS clinical trials, active renal, neurologic and vasculitis disease at baseline, elevated baseline anti-dsDNA and BLyS, and low C3 were modest independent predictors of moderate to severe flare over 52 weeks of longitudinal clinical evaluation [40]. It seems likely that biological heterogeneity between SLE patients is implicated in these varied correlations between immunological measurements and disease activity. To date, the clinical utility of classical serologic markers of disease activity, used alone or in combination, has been relatively limited.

5. Soluble mediator immune pathways in SLE pathogenesis

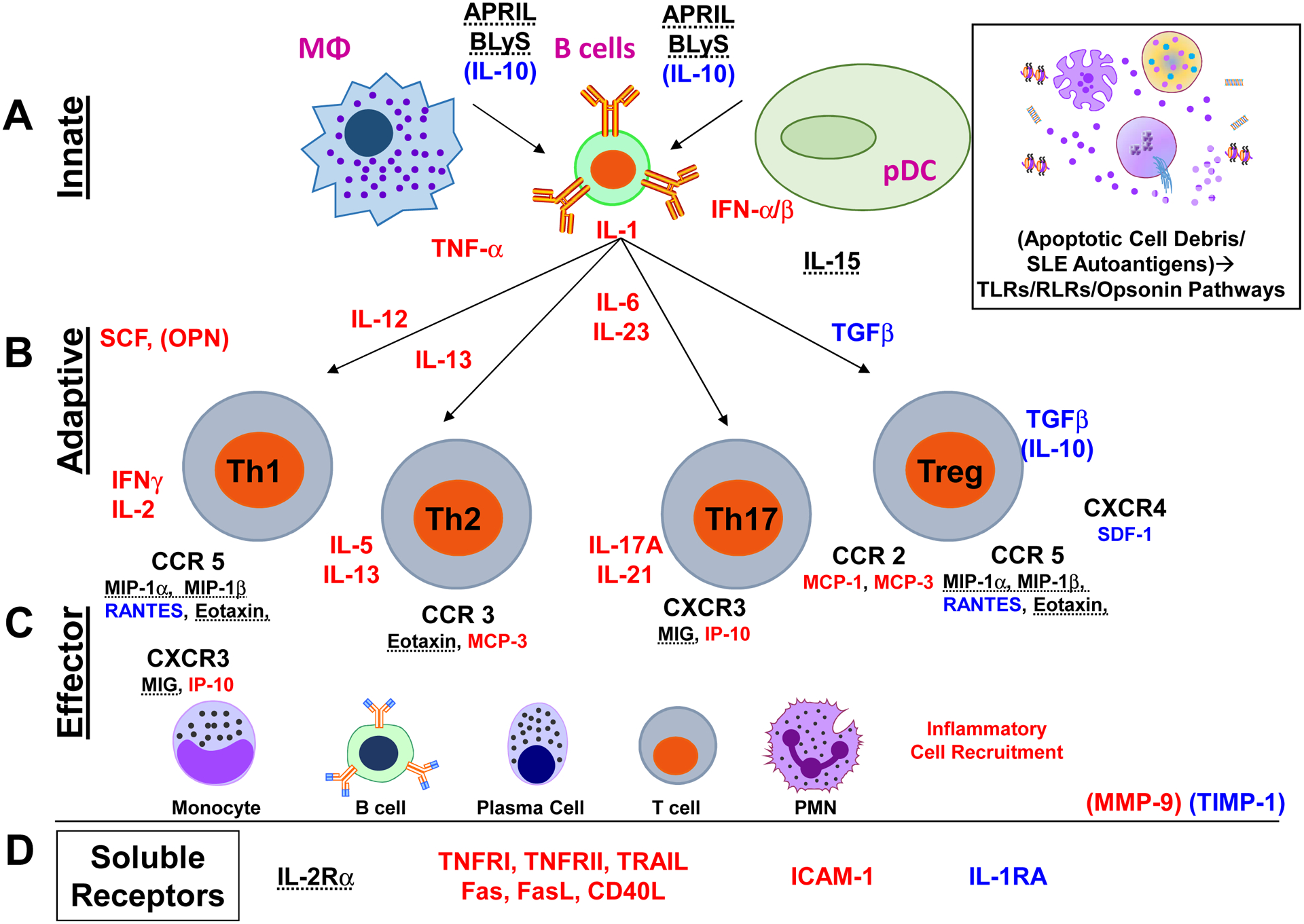

Lupus pathogenesis is driven by immune dysregulation [7, 8] that persists throughout disease [44–50]. In addition to clinical heterogeneity, lupus patients have recently been found to demonstrate diverse and varied immune pathway alterations, as outlined in Figure 1. The first phase of the immune response, innate immunity (Figure 1A), senses initial danger signals to facilitate phagocytosis and clearance of infectious pathogens. Lupus autoantigens that are normally not immunogenic and contained within the nucleus, include nucleic acids, histones, and ribonuclear proteins [51]. In SLE, these antigens are modified and perceived by the immune system as non-self as the result of enhanced cell death coupled with decreased clearance of cellular debris and immune system activation (Figure 1A, inset) [52]. These nuclear particles can trigger RNA and DNA sensing pathways via interaction with RIG-I like receptors (RLRs, including RIG-I and MDA5 [RNA]), toll like receptors (TLRs, including TLR3 [dsRNA], TLR7/8 [ssRNA], and TLR9 [DNA]), and cytoplasmic DNA sensors (including cGAS) [53]. In addition to triggering the release of type I interferons (IFNα/β), such ligand-receptor interactions also stimulate the production of other innate immune mediators, including IL-1 and TNF-α superfamily mediators (Figure 1A). These innate responses activate antigen presenting cells, leading to increased antigen presentation to T-lymphocytes [54].

Figure 1. Summary of altered soluble mediators in SLE patients associated with heightened clinical disease activity and risk of imminent clinical disease flare.

Inflammatory mediators significantly higher in SLE patients with impending disease flare (compared to NF/SNF and HC) are listed in red. Those mediators found to be higher in SLE patients compared to HC, but with levels variable (cohort-dependent) between SLE patients, are dashed. SLE patients with impending disease flare have increased innate (A) and adaptive (B) inflammatory mediators, including those from Th1, Th2, and Th17 pathways. In addition, inflammatory chemokines (C) and soluble TNFR superfamily members (D) are elevated in these patients. SLE patients who are in a period of non-flare (NF/SNF groups, compared to Pre-flare and HC) have higher regulatory mediators, including IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-1RA, listed in blue.

T-lymphocytes are the coordinators of the adaptive immune response (Figure 1B). Full T-lymphocyte activation requires: (i) presentation of antigen on the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) of an antigen presenting cell (APC; macrophages, dendritic cells, or B-lymphocytes) to the T-cell receptor (TCR) on the T-lymphocyte, (ii) interactions of cognate co-stimulatory molecules between the APC and T-lymphocyte, and (iii) soluble mediator communication between the APC and T-lymphocyte to determine T-lymphocyte differentiation and downstream effector responses [55]. The presence of soluble mediators drives activation and differentiation of T-lymphocytes. Multiple immune mediator-driven T-lymphocyte activation pathways are implicated in SLE pathogenesis, including enhanced (Figure 1B, highlighted in red) effector Th1 (IL-12→IFN-γ, IL-2), Th2 (IL-13→IL-5, IL-13), and Th17 (IL-6, IL-23→ IL-17A, IL-21) pathways [7], attenuated T-regulatory (Treg) responses (Figure 1B, highlighted in blue), including reduced TGF-β [56] and IL-10 [57]. T-follicular helper (Tfh) cell responses are augmented, which select high-affinity, antibody-producing B cells for clonal expansion in germinal centers [58]. Of particular interest are multi-function inflammatory mediators that bridge innate and adaptive immunity, including stem cell factor (SCF) and osteopontin (OPN). Both SCF [59] and OPN [60] promote multiple adaptive immunity pathways and contribute to downstream organ damage in SLE [61–63]. The effector response is orchestrated by various chemokines, which recruit specific immune cell populations to sites of inflammation and tissue damage, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocyte populations [64] (Figure 1C).

Tumor necrosis factor TNF receptor superfamily members serve as co-stimulatory molecules on B and T-lymphocytes and form a prototypic pro-inflammatory system that contributes to all phases of the immune response [65] (Figure 1D). The ligand/receptor pairings are either membrane bound or can be cleaved by proteases as soluble proteins which either block ligand/receptor interactions or initiate receptor-mediated signal transduction. The classical ligand TNF-α interacts with two receptors: TNFRI (p55) and TNFRII (p75), both of which have been associated with altered SLE disease activity [66]. In addition, expression and cleavage of Fas, FasL [67], and CD40L (CD154) [68] are increased in SLE patients. BLyS and APRIL, key regulators of B cell survival and differentiation, are important SLE therapeutic targets [69], with belimumab being the first FDA-approved SLE medication in over 50 years [27]. Immune cell activation leads to proteolytic cleavage of TNFRs and other immune receptors, like IL-2Rα (CD25) by metalloproteinases, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTs) [70]. MMP-9 and its inhibitor, tissue inhibitor matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, are expressed by PBMCs and detected in the circulation of SLE patients [71] (Figure 1D). In addition to proteolytic receptor cleavage, MMPs have also been found to synergize with chemokines to recruit leukocytes to sites of inflammation [72].

6. Soluble mediators in clinical disease activity and flare prediction

Promising recent studies have used soluble mediator levels to assess clinical disease activity and predict imminent flare in SLE [16, 61, 73–75]. Previous work in this area was limited by focusing on a more modest panel of soluble mediators and considering all heterogeneous SLE patients together in the same category. A cross-sectional study by Guthridge JM et al. evaluated 91 SLE patients with low disease activity (SELENA-SLEDAI ≤3) vs. 98 SLE patients with active disease (SELENA-SLEDAI>3). This study found no fewer than seven clusters of SLE patients based on soluble mediators and associated transcriptional and cellular activation profiles [44]. Each cluster was enriched in soluble mediators from varied immune system pathways, suggesting that a broad evaluation is necessary to capture the association of blood biomarkers with changes in clinical disease activity and risk of imminent flare. While some immune mediators have been associated with particular clinical disease manifestations, especially lupus nephritis, it has still been difficult to identify a coherent panel of biomarkers reflective of clinical disease activity at the time of blood sampling [44, 47, 66, 74–76]. An alternate hypothesis that immune mediator profiles are altered prior to changes in clinical disease activity and flare has gained traction in recent years.

Munroe ME, et al [47, 49] examined a panel of 52 soluble mediators, measured in plasma by xMAP multiplex and ELISA assays, including innate and adaptive cytokines, chemokines, as well as soluble receptors and TNF superfamily members (Figure 1). In an initial study [49], European American (EA) SLE patients with stable mild to moderately active disease who flared in 6 or 12 weeks after assessment were compared at baseline (pre-flare, PF, n=28) to demographically matched SLE patients without impending flare (nonflare, NF, n=28), and healthy controls. In addition, the same SLE patients were followed longitudinally during both pre-flare and self-nonflare (SNF) periods (n = 13). Flares were defined by the SELENA-SLEDAI scoring system (SSFI). Compared to NF and SNF samples, PF samples had significant alterations (p<0.01 after adjusting for multiple comparison) in 27 of 52 soluble mediators at baseline, with increased levels of pro-inflammatory mediators, including innate, adaptive, and effector/chemokine mediators. Conversely, regulatory cytokines, including IL-10 and native TGF-β1, were higher in NF and SNF samples at baseline.

Results were confirmed in AA SLE patients [47], where 18 patients with impeding flare (PF) by SSFI were compared to themselves during a comparable, clinically stable period (SNF, n=18), or to demographically matched patients without impending flare (NF, n=13 per group). Significant alterations in 34 of 52 soluble mediators were observed at baseline (PF), with increased levels of innate (IL-1α and type I IFN) and adaptive cytokines (Th1-, Th2-, and Th17-type), as well as IFN-associated chemokines and soluble TNF superfamily members. In contrast, stable SLE patients (NF and SNF) exhibited increased levels of the regulatory mediators IL-10 (q≤0.0045) and native TGF-β1 (q≤0.0004) after adjusting for multiple comparison.

Similar to EA SLE patients, pre-flare AA SLE patients were found to have increased levels of IFN associated chemokines, TNF superfamily (e.g. FasL, CD40L, and TNFRII), and Th17 mediators that significantly contributed to the Soluble Mediator Score (SMS). Unlike pre-flare EA SLE patients, who had significant alterations in innate IL-1 family members that contributed to the EA SMS, AA patients had increased type I IFN levels that contributed to the AA SMS, which is consistent with known ancestral differences in the type I IFN signature in SLE [77]. Interestingly, IFN-associated chemokines, including IP- 10 and MCP-3, were altered in both AA and EA SLE patients. In addition, SCF levels were consistently elevated prior to disease flare in both AA and EA SLE patients. SCF has been implicated in the production of IL-6 and Th17 development, with increased secretion of IL-17A and IL-21, all of which were elevated in pre-flare AA and EA SLE patients. Nonetheless, not all cytokines were associated with flare in these studies. Levels of BLyS and APRIL were increased in SLE patients, but did not differ between PF and NF. Other studies have however suggested the importance of those mediators in clinical disease activity and flare [40, 45, 46, 78], likely reflecting the heterogeneity of immune profiles in different SLE populations. Levels of IL-15, IL-2Rα (CD25), along with chemokines induced by IFN, including macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), and MIP-1β, displayed varied responses between both groups of SLE patients, yet were higher in SLE patients compared to healthy controls. These same analytes [48, 76, 79], along with OPN [61, 80] and MMP-9 [71, 81], have been shown to be associated with heightened clinical disease activity in other SLE studies.

7. A global flare risk soluble mediator score predicts imminent clinical disease flare

As described above and in Figure 1, the number and type of immune pathways altered in association with clinical disease activity and impending flare vary widely, both between lupus patients and even within the same lupus patient over time. Individual markers are unlikely to universally correlate with the development of flares. Yet, the overall balance between inflammatory and regulatory mediators, particularly when considered en masse, may correlate with future disease activity and be predictive of impending clinical disease flare [47–50]. That immune pathway alterations have been shown to precede changes in clinical disease activity associated with impending flare [46, 47, 49] suggests that these parameters might be harnessed into an actionable predictive measure.

It is with this intent that a global flare risk soluble mediator score (SMS) was derived by the sum of log-transformed, normalized peripheral soluble mediator levels collected at time of sample procurement and weighted (Spearman correlation) by their association with future clinical disease activity (SELENA-SLEDAI) when clinical disease flare occurred [47, 49]. Of note, prior to disease flare, baseline SELENA-SLEDAI scores were similar between PF vs. NF (p≥0.2451) and SNF (p≥0.5387) SLE patients at time of sample procurement, irrespective of race. This indicates that concurrent clinical disease activity is unlikely to be predictive of future diseae activity and flare. However, the flare risk SMS was significantly higher in PF compared to NF and SNF samples at baseline in both EA [49] and AA patients [47] (Flare vs NF or SNF, p<0.0001), reflective of the immune system changes that occur preceding changes in clinical disease activity and impending flare.

Relationships between changes in immune mediator levels, clinical disease activity over time, and the resulting flare risk SMS are exemplified in Figure 2. As illustrated in Figure 2A, prior to increased clinical disease activity that leads to flare, immune profiles are likely to be inflammatory in nature (red phase of the illustration), resulting in a positive flare risk SMS (increasing dotted line) that is followed by increased clinical disease activity (increasing solid line). As patients are treated for flare (* at peak of clinical disease activity line) and proceed toward clinical resolution of flare and stabilization of clinical disease activity (decreasing solid line), regulatory mediators are relatively increased compared to pro-inflammatory mediators (blue phase of the illustration). This is maintained (sustained dotted [SMS] and solid [disease activity] lines) until a pre-flare period resumes, regulatory mediators are no longer able to contain lupus-associated inflammation, and pro-inflammatory mediators increase (with increasing SMS, dotted line) ahead of the next imminent clinical disease flare (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Models of altered soluble mediators and flare risk soluble mediator score (SMS) relative to changes in clinical disease activity (SELENA-SLEDAI) in SLE.

(A) Plasma levels of immune mediators are altered (increased or decreased), reflected in a flare risk SMS (blue dotted line, left y-axis) prior to changes in clinical disease activity (solid line, right y-axis). Prior to imminent clinical disease flare, pro-inflammatory mediators dominate (red profile), whereas regulatory mediators (blue profile) are more likely to be elevated after treatment (*) for clinical disease flare and during more stable (non-flare) periods of clinical disease activity. (B) Model of a flare risk SMS (blue dotted line, left y-axis) vs. clinical disease activity (black solid line, right y-axis) over time in a lupus patient with waxing/waning disease activity with clinical flares (red squares = times of clinical disease flare). (C) Model of a flare risk SMS (blue dotted line, left y-axis) vs. clinical disease activity (black solid line, right y-axis) over time in a lupus patient active disease, but no impending disease flare. (D) Model of a flare risk SMS (blue dotted line, left y-axis) vs. clinical disease activity (black solid line, right y-axis) over time in a lupus patient with quiescent or minimally active, stable clinical disease (no flare).

The practical relevance of the flare risk SMS over time, relative to changes in clinical disease activity (e.g. SLEDAI scores), is illustrated in Figure 2B–D. A pre-flare SLE patient with waxing and waning disease activity over time (x-axis), Figure 2B, would likely have an elevated and positive flare risk SMS (dotted line, left y-axis) prior to clinical flare (solid line, right y-axis). Then the SMS would decrease in response to treatment and increase again prior to the next flare (Figure 2B). In contrast, in an SLE patient with clinically active disease, but no impending clinical disease flare, illustrated in Figure 2C, both the SMS (dotted line, left y-axis) and disease activity (solid line, right y-axis) scores may change somewhat over time, yet the flare risk SMS stays near or below zero, without the defining increase that signals an impending clinical flare. Finally, a non-flare SLE patient with clinically quiescent or mildly active, stable disease would most likely have negative, relatively stable SMS over time (Figure 2D).

These illustrations are further supported by a clinical trial protocol developed by Merrill JT et al. [45, 46] whereby patients are given serial, repeated dexamethasone treatments to suppress clinical disease activity, then longitudinally followed in the absence of steroid until time of disease flare. Treatment with dexamethasone decreased inflammatory mediators ahead of decreases in clinical disease activity. After treatment was withdrawn and patients were longitudinally and serially followed, inflammatory mediators, including IFN and TNF superfamily members, once again increased prior to the appearance of clinical disease flare [45, 46]. These findings support the idea that following immune profiles over time may allow providers to intervene prior to the onset of clinical disease flare.

8. Discussion

Panels of plasma cytokines and other immune mediators represent an array of immune pathways relevant to SLE pathogenesis, and can provide insight into SLE immunologic activity beyond what can be judged by clinical features and available serologic markers. Patterns of change in immune mediators characterized by increased pro-inflammatory adaptive cytokines and shed TNF receptors and decreased regulatory mediators were found to accompany SLE flares. Such cytokine alterations reflective of a positive flare risk SMS were evident several weeks prior to clinical flare development, and persisted until time of concurrent clinical flare when medical intervention occurred [47, 49]. The presence of a positive flare risk SMS was found to be highly accurate in clinical flare prediction. In addition, the presence of negative flare risk SMS was indicative of stable disease activity, which may allow for adjustments in treatment to offset toxic side effects [41].

The flare risk SMS in SLE is reminiscent of an immune mediator-informed algorithm to characterize clinical disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis [82]. The SLE flare risk SMS incorporates all mediators tested with no requirement for cut off values to establish positivity, therefore harnessing a wide range of immune mediator information as well as waiving any requirement for a priori knowledge of the inflammatory pathways contributing to flare in a particular patient. By providing a broad survey of immune pathway activation, the score showed remarkable consistency despite immunologic and clinical heterogeneity among patients. This is in contrast to traditional biomarkers incorporated in the SELENA-SLEDAI, which are not necessarily the earliest, nor sufficient biologic signals of worsening disease.

The flare risk SMS also allowed the assessment of the cumulative contribution of multiple plasma mediators at baseline time of sample procurement (PF) in relation to follow-up clinical disease activity at time of flare. Mediators whose baseline levels had stronger correlations with disease activity at the time of flare contributed most to the score, and therefore the overall level of inflammation correlated with the level of disease flare. Notably, there was minimal association of baseline immune alterations with baseline disease activity, irrespective of future flare status. Those results await validation and refinement in longitudinal, prospective, multiethnic studies. Such studies are needed to assess changes in the SMS in response to flare treatment, as well as changes associated with tapering immune modulators in patients with stable disease, as even patients with long-term quiescent disease are at risk for disease flare [83]. Finally, utilizing the SMS for selection of patients for clinical trials of novel, directed therapies may improve clinical trial outcomes.

9. Conclusion

Clinical flares have been associated with a host of adverse outcomes in SLE, including progressive damage accrual, increased morbidity and mortality, and a significant socioeconomic burden. Reducing the frequency and intensity of flares is a major treatment objective and a quality of care measure in SLE. With rapidly growing insight regarding the immune-mediated pathogenesis of SLE, it has been increasingly understood that clinical flares represent a late manifestation of underlying immune perturbations. Unfortunately, such perturbations are usually treated reactively after becoming clinically manifest. Beyond assessing disease activity and flare at the time of clinical encounter, clinicians must also consider the potential for disease exacerbation in the following weeks and months. Identification of individuals at risk of impeding flare could prompt closer clinical monitoring, enhance self-awareness and management, and enable preemptive treatment.

Recent studies support the idea that panels of plasma cytokines and other immune mediators can improve our ability to predict disease flare beyond traditional clinical and serological markers. These soluble mediators can incorporate the breadth of immune dysregulation associated with SLE and reflect the immune status of individual patients. Changes in the balance of plasma inflammatory and regulatory mediators are detectable several weeks prior to clinical flare and are highly predictive of imminent flare occurrence. This novel immunologic tool could enhance clinical understanding of SLE disease activity and flare, and assist in the comprehensive management of the individual patient.

Heightened lupus disease activity and flare increase risk of permanent organ damage.

Lupus flares decrease quality of life and productivity with increased medical costs.

Multiple immune pathways are dysregulated prior to disease flare.

Baseline soluble mediator levels correlate with future disease activity and flare.

Acknowledgements

This review was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under award number R44AI142967 (MEM) and the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology under award numbers AR16-014 (MEM) and AR18–019 (EJ). TBN has received grant support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases under award numbers AR060861, AR057781, AR065964, AI071651, as well as the Lupus Research Foundation. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. AT has received consulting fees from Neovacs SA, Exagen, Inc. and Progentec Diagnostics, Inc. EJ and MP are employed by Progentec Diagnostics, Inc. TBN has received research support from EMD Serono and Janssen, Inc., and has consulted for Thermo Fisher, Progentec Diagnostics, and Inova, Inc. MEM is partially employed by and receives research support from Progentec Diagnostics, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Maria NI, Davidson A. Emerging areas for therapeutic discovery in SLE. Curr Opin Immunol, 2018;55:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tsokos GC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med, 2011;365:2110–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, Brinks R, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis & rheumatology, 2019;71:1400–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum, 2012;64:2677–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum, 1997;40:1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Munroe ME, Young KA, Kamen DL, Guthridge JM, Niewold TB, Costenbader KH et al. Discerning Risk of Disease Transition in Relatives of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients Utilizing Soluble Mediators and Clinical Features. Arthritis & rheumatology, 2017;69:630–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lu R, Munroe ME, Guthridge JM, Bean KM, Fife DA, Chen H et al. Dysregulation of Innate and Adaptive Serum Mediators Precedes Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Classification and Improves Prognostic Accuracy of Autoantibodies J Autoimmun, 2016;74:182–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Munroe ME, Lu R, Zhao YD, Fife DA, Robertson JM, Guthridge JM et al. Altered type II interferon precedes autoantibody accrual and elevated type I interferon activity prior to systemic lupus erythematosus classification. Ann Rheum Dis, 2016;75:2014–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barr SG, Zonana-Nacach A, Magder LS, Petri M. Patterns of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum, 1999;42:2682–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tselios K, Gladman DD, Touma Z, Su J, Anderson N, Urowitz MB. Disease course patterns in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus, 2019;28:114–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Stoll T, Sutcliffe N, Mach J, Klaghofer R, Isenberg DA. Analysis of the relationship between disease activity and damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus--a 5-yr prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2004;43:1039–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ugarte-Gil MF, Acevedo-Vasquez E, Alarcon GS, Pastor-Asurza CA, Alfaro-Lozano JL, Cucho-Venegas JM et al. The number of flares patients experience impacts on damage accrual in systemic lupus erythematosus: data from a multiethnic Latin American cohort. Ann Rheum Dis, 2015;74:1019–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fernandez D, Kirou KA. What Causes Lupus Flares? Current rheumatology reports, 2016;18:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kan HJ, Song X, Johnson BH, Bechtel B, O’Sullivan D, Molta CT. Healthcare utilization and costs of systemic lupus erythematosus in Medicaid. BioMed research international, 2013;2013:808391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Drenkard C, Bao G, Dennis G, Kan HJ, Jhingran PM, Molta CT et al. Burden of systemic lupus erythematosus on employment and work productivity: data from a large cohort in the southeastern United States. Arthritis care & research, 2014;66:878–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gensous N, Marti A, Barnetche T, Blanco P, Lazaro E, Seneschal J et al. Predictive biological markers of systemic lupus erythematosus flares: a systematic literature review. Arthritis Res Ther, 2017;19:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Griffiths B, Mosca M, Gordon C. Assessment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and the use of lupus disease activity indices. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology, 2005;19:685–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum, 1992;35:630–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, Grossman J, Hahn BH, Sammaritano LR et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med, 2005;353:2550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol, 2002;29:288–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Allen E, Farewell V, Akil M, Bruce IN et al. BILAG 2004. Development and initial validation of an updated version of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group’s disease activity index for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2005;44:902–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thanou A, Merrill JT. Top 10 things to know about lupus activity measures. Current rheumatology reports, 2013;15:334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hay EM, Bacon PA, Gordon C, Isenberg DA, Maddison P, Snaith ML et al. The BILAG index: a reliable and valid instrument for measuring clinical disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Q J Med, 1993;86:447–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yee CS, Farewell V, Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Teh LS, Griffiths B et al. British Isles Lupus Assessment Group 2004 index is valid for assessment of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum, 2007;56:4113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cresswell L, Yee CS, Farewell V, Rahman A, Teh LS, Griffiths B et al. Numerical scoring for the Classic BILAG index. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2009;48:1548–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yee CS, Cresswell L, Farewell V, Rahman A, Teh LS, Griffiths B et al. Numerical scoring for the BILAG-2004 index. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Navarra SV, Guzman RM, Gallacher AE, Hall S, Levy RA, Jimenez RE et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet, 2011;377:721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Furie R, Khamashta M, Merrill JT, Werth VP, Kalunian K, Brohawn P et al. Anifrolumab, an Anti-Interferon-alpha Receptor Monoclonal Antibody, in Moderate-to-Severe Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis & rheumatology, 2017;69:376–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].van Vollenhoven RF, Mosca M, Bertsias G, Isenberg D, Kuhn A, Lerstrom K et al. Treat-to-target in systemic lupus erythematosus: recommendations from an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis, 2014;73:958–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].van Vollenhoven R, Voskuyl A, Bertsias G, Aranow C, Aringer M, Arnaud L et al. A framework for remission in SLE: consensus findings from a large international task force on definitions of remission in SLE (DORIS). Ann Rheum Dis, 2017;76:554–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Askanase AD, Nguyen SC, Costenbader K, Lim SS, Kamen D, Aranow C et al. Comparison of the Lupus Foundation of America-Rapid Evaluation of Activity in Lupus to More Complex Disease Activity Instruments As Evaluated by Clinical Investigators or Real-World Clinicians. Arthritis care & research, 2018;70:1058–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Thanou A, James JA, Arriens C, Aberle T, Chakravarty E, Rawdon J et al. Scoring systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) disease activity with simple, rapid outcome measures. Lupus science & medicine, 2019;6:e000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ruperto N, Hanrahan LM, Alarcon GS, Belmont HM, Brey RL, Brunetta P et al. International consensus for a definition of disease flare in lupus. Lupus, 2011;20:453–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gordon C, Sutcliffe N, Skan J, Stoll T, Isenberg DA. Definition and treatment of lupus flares measured by the BILAG index. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2003;42:1372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Petri M, Buyon J, Kim M. Classification and definition of major flares in SLE clinical trials. Lupus, 1999;8:685–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Kagal A, Hallett D. Accurately describing changes in disease activity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Rheumatol, 2000;27:377–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Isenberg DA, Allen E, Farewell V, D’Cruz D, Alarcon GS, Aranow C et al. An assessment of disease flare in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of BILAG 2004 and the flare version of SELENA. Ann Rheum Dis, 2011;70:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Thanou A, Chakravarty E, James JA, Merrill JT. How should lupus flares be measured? Deconstruction of the Safety of Estrogen in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment-Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index flare index. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2014;53:2175–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Petri M, Singh S, Tesfasyone H, Malik A. Prevalence of flare and influence of demographic and serologic factors on flare risk in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study. J Rheumatol, 2009;36:2476–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Petri MA, van Vollenhoven RF, Buyon J, Levy RA, Navarra SV, Cervera R et al. Baseline Predictors of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Flares: Data From the Combined Placebo Groups in the Phase III Belimumab Trials. Arthritis Rheum, 2013;65:2143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zen M, Saccon F, Gatto M, Montesso G, Larosa M, Benvenuti F et al. Prevalence and predictors of flare after immunosuppressant discontinuation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in remission. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2020;59:1591–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fu SM, Dai C, Zhao Z, Gaskin F. Anti-dsDNA Antibodies are one of the many autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. F1000Res, 2015;4:939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Buyon JP, Tamerius J, Belmont HM, Abramson SB. Assessment of disease activity and impending flare in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Comparison of the use of complement split products and conventional measurements of complement. Arthritis Rheum, 1992;35:1028–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Guthridge JM, Lu R, Tran LT, Arriens C, Aberle T, Kamp S et al. Adults with systemic lupus exhibit distinct molecular phenotypes in a cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine, 2020;20:100291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Merrill JT, Immermann F, Whitley M, Zhou T, Hill A, O’Toole M et al. The Biomarkers of Lupus Disease Study: A Bold Approach May Mitigate Interference of Background Immunosuppressants in Clinical Trials. Arthritis & rheumatology, 2017;69:1257–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lu R, Guthridge JM, Chen H, Bourn RL, Kamp S, Munroe ME et al. Immunologic findings precede rapid lupus flare after transient steroid therapy. Scientific reports, 2019;9:8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Munroe ME, Vista ES, Merrill JT, Guthridge JM, Roberts VC, James JA. Pathways of impending disease flare in African-American systemic lupus erythematosus patients. J Autoimmun, 2017;78:70–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Raymond WD, Eilertsen GO, Nossent J. Principal component analysis reveals disconnect between regulatory cytokines and disease activity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Cytokine, 2019;114:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Munroe ME, Vista ES, Guthridge JM, Thompson LF, Merrill JT, James JA. Pro-inflammatory adaptive cytokines and shed tumor necrosis factor receptors are elevated preceding systemic lupus erythematosus disease flare. Arthritis & rheumatology, 2014;66:1888–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yao Y, Wang JB, Xin MM, Li H, Liu B, Wang LL et al. Balance between inflammatory and regulatory cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus. Genet Mol Res, 2016;15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Fenton K. The effect of cell death in the initiation of lupus nephritis. Clin Exp Immunol, 2015;179:11–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Munoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M, Manfredi AA, Herrmann M. The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2010;6:280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kato H, Fujita T. RIG-I-like receptors and autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Immunol, 2015;37:40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Deretic V, Saitoh T, Akira S. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013;13:722–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zharkova O, Celhar T, Cravens PD, Satterthwaite AB, Fairhurst AM, Davis LS. Pathways leading to an immunological disease: systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2017;56:i55–i66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ohtsuka K, Gray JD, Stimmler MM, Horwitz DA. The relationship between defects in lymphocyte production of transforming growth factor-beta1 in systemic lupus erythematosus and disease activity or severity. Lupus, 1999;8:90–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Talaat RM, Mohamed SF, Bassyouni IH, Raouf AA. Th1/Th2/Th17/Treg cytokine imbalance in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients: Correlation with disease activity. Cytokine, 2015;72:146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yap DY, Lai KN. Pathogenesis of Renal Disease in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus-The Role of Autoantibodies and Lymphocytes Subset Abnormalities. International journal of molecular sciences, 2015;16:7917–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ray P, Krishnamoorthy N, Oriss TB, Ray A. Signaling of c-kit in dendritic cells influences adaptive immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2010;1183:104–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Clemente N, Raineri D, Cappellano G, Boggio E, Favero F, Soluri MF et al. Osteopontin Bridging Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Autoimmune Diseases. Journal of immunology research, 2016;2016:7675437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wirestam L, Enocsson H, Skogh T, Padyukov L, Jonsen A, Urowitz MB et al. Osteopontin and Disease Activity in Patients with Recent-onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Results from the SLICC Inception Cohort. J Rheumatol, 2019;46:492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sung SJ, Fu SM. Interactions among glomerulus infiltrating macrophages and intrinsic cells via cytokines in chronic lupus glomerulonephritis. J Autoimmun, 2019:102331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Abreu-Velez AM, Girard JG, Howard MS. Antigen presenting cells in the skin of a patient with hair loss and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Am J Med Sci, 2009;1:205–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Morell M, Varela N, Maranon C. Myeloid Populations in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2017;53:198–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Croft M, Benedict CA, Ware CF. Clinical targeting of the TNF and TNFR superfamilies. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2013;12:147–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Davas EM, Tsirogianni A, Kappou I, Karamitsos D, Economidou I, Dantis PC. Serum IL-6, TNFalpha, p55 srTNFalpha, p75srTNFalpha, srIL-2alpha levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol, 1999;18:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Tinazzi E, Puccetti A, Gerli R, Rigo A, Migliorini P, Simeoni S et al. Serum DNase I, soluble Fas/FasL levels and cell surface Fas expression in patients with SLE: a possible explanation for the lack of efficacy of hrDNase I treatment. Int Immunol, 2009;21:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Desai-Mehta A, Lu L, Ramsey-Goldman R, Datta SK. Hyperexpression of CD40 ligand by B and T cells in human lupus and its role in pathogenic autoantibody production. J Clin Invest, 1996;97:2063–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Vincent FB, Saulep-Easton D, Figgett WA, Fairfax KA, Mackay F. The BAFF/APRIL system: emerging functions beyond B cell biology and autoimmunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2013;24:203–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Malemud CJ. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in health and disease: an overview. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library, 2006;11:1696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Matache C, Stefanescu M, Dragomir C, Tanaseanu S, Onu A, Ofiteru A et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and its natural inhibitor TIMP-1 expressed or secreted by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun, 2003;20:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Song J, Wu C, Korpos E, Zhang X, Agrawal SM, Wang Y et al. Focal MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity at the blood-brain barrier promotes chemokine-induced leukocyte migration. Cell Rep, 2015;10:1040–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Adhya Z, El Anbari M, Anwar S, Mortimer A, Marr N, Karim MY. Soluble TNF-R1, VEGF and other cytokines as markers of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Lupus, 2019;28:713–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Ruchakorn N, Ngamjanyaporn P, Suangtamai T, Kafaksom T, Polpanumas C, Petpisit V et al. Performance of cytokine models in predicting SLE activity. Arthritis Res Ther, 2019;21:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Zhou H, Li B, Li J, Wu T, Jin X, Yuan R et al. Dysregulated T Cell Activation and Aberrant Cytokine Expression Profile in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Mediators of inflammation, 2019;2019:8450947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhang RJ, Zhang X, Chen J, Shao M, Yang Y, Balaubramaniam B et al. Serum soluble CD25 as a risk factor of renal impairment in systemic lupus erythematosus - a prospective cohort study. Lupus, 2018;27:1100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ko K, Koldobskaya Y, Rosenzweig E, Niewold TB. Activation of the Interferon Pathway is Dependent Upon Autoantibodies in African-American SLE Patients, but Not in European-American SLE Patients. Frontiers in immunology, 2013;4:309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Gordon C, Wofsy D, Wax S, Li Y, Pena Rossi C, Isenberg D. Post-hoc analysis of the Phase II/III APRIL-SLE study: Association between response to atacicept and serum biomarkers including BLyS and APRIL. Arthritis & rheumatology, 2017;69:122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Apostolidis SA, Lieberman LA, Kis-Toth K, Crispin JC, Tsokos GC. The dysregulation of cytokine networks in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Interferon Cytokine Res, 2011;31:769–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Wirestam L, Frodlund M, Enocsson H, Skogh T, Wettero J, Sjowall C. Osteopontin is associated with disease severity and antiphospholipid syndrome in well characterised Swedish cases of SLE. Lupus science & medicine, 2017;4:e000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ellinghaus U, Cortini A, Pinder CL, Le Friec G, Kemper C, Vyse TJ. Dysregulated CD46 shedding interferes with Th1-contraction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Immunol, 2017;47:1200–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Curtis JR, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Knevel R, Huizinga TW, Haney DJ, Shen Y et al. Validation of a novel multibiomarker test to assess rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis care & research, 2012;64:1794–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Steiman AJ, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Prolonged serologically active clinically quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: frequency and outcome. J Rheumatol, 2010;37:1822–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]