Abstract

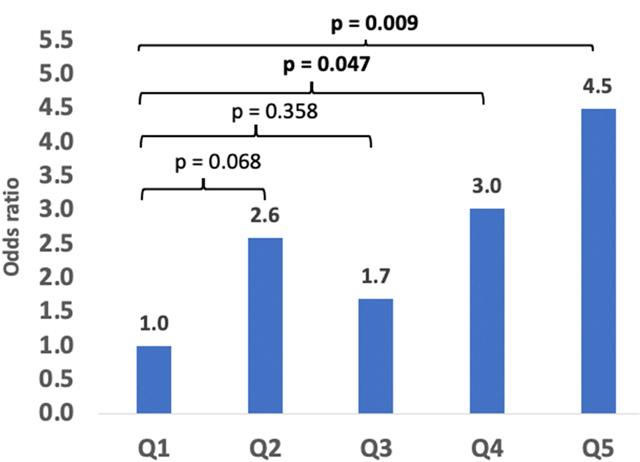

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed female cancer and the second leading cause of death in women in the US, including Hawaii. Accumulating evidence suggests that aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), the primary metabolite of the herbicide glyphosate—a probable human carcinogen, may itself be carcinogenic. However, the relationship between urinary AMPA excretion and breast cancer risk in women is unknown. In this pilot study, we investigated the association between pre-diagnostic urinary AMPA excretion and breast cancer risk in a case-control study of 250 predominantly postmenopausal women: 124 cases and 126 healthy controls (individually matched on age, race/ethnicity, urine type, date of urine collection, and fasting status) nested within the Hawaii biospecimen subcohort of the Multiethnic Cohort. AMPA was detected in 90% of cases and 84% of controls. The geometric mean of urinary AMPA excretion was nearly 38% higher among cases vs. controls (0.087 vs 0.063 ng AMPA/mg creatinine) after adjusting for race/ethnicity, age and BMI. A 4.5-fold higher risk of developing breast cancer in the highest vs. lowest quintile of AMPA excretion was observed (ORQ5 vs. Q1: 4.49; 95% CI: 1.46–13.77; ptrend=0.029). To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively examine associations between urinary AMPA excretion and breast cancer risk. Our preliminary findings suggest that AMPA exposure may be associated with increased breast cancer risk; however, these results require confirmation in a larger population to increase study power and permit careful examinations of race/ethnicity differences.

Keywords: urine, aminomethyphosphonic acid, glyphosate, breast cancer, Multiethnic Cohort

Graphical Abstract

Odds ratio of breast cancer as a function of quintiles of urinary aminomethylphosphonic acid excretion (Q1=lowest, Q5=highest quintiles).

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed female cancer and the second leading cause of death in women in the US, including Hawaii [1, 2]. Estrogen is a well-known contributor to the development of hormone-dependent breast carcinomas [3, 4]. As such, any factor that interferes with estrogen homeostasis, theoretically, has the ability to influence breast cancer risk and, thus, merits further study.

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous compounds that interfere with normal hormonal actions in humans [5] and consist of a very heterogenous group of compounds that include, but are not limited to, pesticides (methoxychlor, chlorpyrifos, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and nonpersistent environmental EDCs such as bisphenol A (BPA; used during the manufacturing of plastics/resins), phthalates (used as plasticizers), triclosan (TCS; antibacterial/antifungal agents), and parabens (used as preservatives) ubiquitously present in modern times [5].

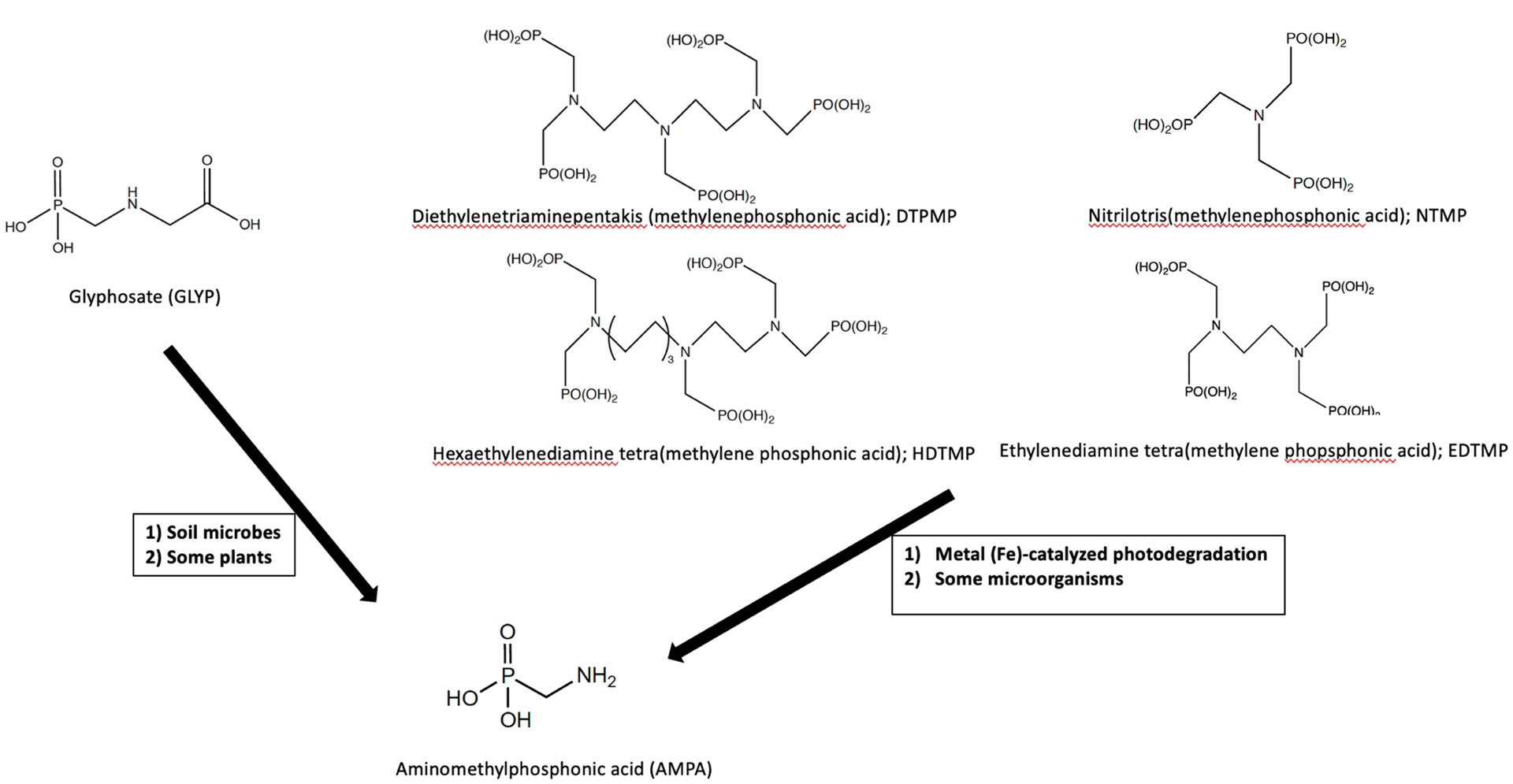

Aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) is the major metabolite resulting from the soil microbial degradation of glyphosate (GLYP) [6, 7], currently the most widely used herbicide worldwide and the subject of ongoing contentious debate regarding its human carcinogenicity among international regulatory bodies [8] with AMPA being more often detected than GLYP [10–12]. AMPA is also the key metabolite of phosphonates found in several household laundry and cleaning detergents [9, 10], which may explain its widespread occurrence in the environment [10–13].

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) cited evidence from in vitro and animal studies showing that AMPA could induce oxidative stress [14]—a characteristic for human carcinogens [15]. In addition, a recent, large study (n>30,000) of farmers’ wives found significant associations between the use of several organophosphate insecticides and elevated breast cancer risk [16]. However, the metabolites of these compounds were not analyzed.

Pesticide metabolites have often been found to be more mobile, persistent, and detrimental than their respective parent compound [17] and, thus, may pose equal or higher risks to humans upon exposure. While most pesticides are ultimately converted to components with less or no toxicity, certain chemical characteristics (i.e., water solubility, vapor pressure) can enable metabolites to become biologically active [17]. AMPA is very water soluble (5.8 g/L near 25°C in water) [18], and has been detected in human urine of non-occupationally exposed humans [19–22] often in a higher percentage of samples than GLYP [19–21].

To complement our ongoing investigations on the associations between breast cancer risk and urinary excretion of EDCs (that currently consists of BPA, phthalates, TCS, and parabens), we sought to expand our research in this pilot study to AMPA, using the same urine samples from the same women within the Multiethnic Cohort (MEC).

Methods

Study population and data collection

This study utilized urine samples from a nested case-control study of breast cancer among mostly postmenopausal women participating in the Hawaii biospecimen subcohort of the MEC. The MEC is a prospective study designed to investigate the associations of dietary, lifestyle, and genetic factors with the incidence of cancer. Study details have been described elsewhere [23]. Briefly, between 1993 and 1996, over 215,000 men and women, ages 45–75 years from five racial/ethnic groups (Japanese American, Native Hawaiian, White, African American, Latino) from Hawaii and Los Angeles, California, were enrolled in the cohort. Potential participants were identified through drivers’ license files, voter registration lists, and Medicare files. At cohort entry, participants completed a self-administered, 26-page questionnaire that included queries on demographic characteristics, anthropometric measures, medical history, family history of cancer, physical activity, dietary habits, supplement use, and reproductive history for women.

The prospective MEC biospecimen subcohort was established from 2001 to 2006 among the surviving cohort members who agreed to provide blood and/or urine specimens and to answer a short questionnaire [24]. Biospecimens were prospectively collected from 36,458 mostly postmenopausal women, 32,243 of whom provided a urine sample. Most participants in Hawaii provided an overnight specimen while those in Los Angeles donated mainly a first morning urine specimen; spot urine was requested otherwise. At the time of urine collection, updated information was collected on tobacco use, weight, medication, supplements, and hormone use. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Hawaii and the University of Southern California. Every participant gave written consent.

Case ascertainment and control selection

Incident invasive breast cancer cases were identified through linkage to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program registries covering Hawaii and California. Breast cancer diagnoses were classified using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition codes C50.0-C50.9 and were restricted to invasive malignancies. For this analysis, we selected 124 Hawaii breast cancer cases and 126 matched controls from an ongoing nested case-control study of breast cancer within the MEC with available urine [25], including 123 matched sets. Cases were selected among those diagnosed after urine collection through December 31, 2016. The time between urine collection and breast cancer diagnosis averaged (± standard deviation) 5.5±3.3 years, with minimum of 0.08 and maximum of 12.2 years. One control was selected for each case and was randomly selected from the eligible pool of women who were alive and free of a breast cancer diagnosis at the time of the case’s diagnosis. Controls were matched to cases on birth year (± 1 year), race/ethnicity (Japanese American, Native Hawaiian, White), date of urine collection (± 1 year), time of blood draw (± 2 hours), and hours fasting prior to blood draw (8–10, >10 hours).

Urinary AMPA and creatinine analysis

All assays were performed at the Analytical Biochemistry Shared Resource of the University of Hawaii Cancer Center. The assays were blinded to the analysts regarding case/control status, and samples were analyzed in randomized order, but samples of cases and their respective controls were always kept in the same analysis batch. Urinary AMPA concentrations were measured by a novel ultra-sensitive liquid chromatography high-resolution accurate-mass mass spectrometry (LC/HRAM-MS) method that included derivatization with 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chloride (Fmoc-Cl) and solid phase extraction (SPE) purification of the resulting adduct [26]. In brief, 0.5 mL of urine were mixed with the internal standard AMPA-13C-15N-d2 (500 ng/mL in water) and diluted with 1 mL of water followed by reversed phase SPE with polymeric sorbents (Strata-X; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The SPE load and wash fractions were mixed with 100 μL of sodium borate buffer (2.6% in water) and 150 μL of Fmoc-Cl (6 mg/mL in acetonitrile) and incubated at 50°C for 20 minutes. After cooling to room temperature, 5 μL of formic acid was added to the reaction mixture and centrifuged. The supernatant was then purified with a SepPak C18 reverse phase SPE cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA), separated by liquid chromatography using a Kinetex EVO C18 analytical column (Phenomenex) and analyzed by LC/HRAM-MS (Q-Exactive, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) with targeted selected ion monitoring by detecting the monoisotopic masses of the protonated analytes (± 5 ppm to account for mass spectrometric inaccuracies). The between-day precision of this assay using pooled urine samples spiked with 0.4 ng/mL AMPA was excellent (CV=5%.) Values below the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ; 0.001 ng/mL) were assigned a value of 0.0005 ng/mL to allow statistical evaluations. Urinary AMPA concentrations were adjusted for creatinine levels to normalize for urine volume [27]. Urinary creatinine was measured by a Cobas MiraPlus clinical chemistry auto analyzer (Roche Diagnostics) using a commercially available creatinine kit (Randox Laboratories, Crumlin, UK) based on the Jaffé reaction. The between-day precision of this assay using pooled urine samples was 8%. The calibration curve was highly linear (r2>0.995).

Statistical Analysis

Breast cancer cases and controls were compared with respect to several demographic characteristics and potential risk factors of interest. Adjusted and unadjusted geometric means of AMPA excretion values were compared between cases and controls, by race/ethnicity, age groups (≤64 y, 65–74 y, 75 y and older), and body mass index (BMI; normal: 18.5–24.9, overweight: 25–29.9, obese: ≥30) at urine collection, using general linear models and a pairwise t-test.

The association of urinary AMPA excretion with the risk of breast cancer was examined using conditional logistic regression with matched sets as strata. AMPA excretion was categorized into quintiles based on the controls. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed for each quintile, using the lowest quintile as a reference. Models were adjusted for potential confounders of postmenopausal breast cancer risk, including BMI at urine collection (continuous), family history of breast cancer (yes, no), age at menarche (<13, 13–14, ≥15 or missing), age at first live birth (≤20 or missing, 21–25, 26–30, ≥31 or nulliparous), menopausal status (pre-, postmenopausal), hormone use (ever, never), tobacco smoking (never, former, current smoker), daily alcohol intake (0, <12 g/d, ≥12 g/d, missing), education (less than college degree, college degree or higher), mammography screening (ever, never), moderate to vigorous physical activity (hours/day, continuous). Dietary factors such as total daily energy intake, healthy eating index-2010 diet score [28], and daily caffeine intake were also considered, but not included in the final model as their inclusion did not change the risk estimates by more than 10% [29]. Linear trend was evaluated by fitting a model with the nominal trend variable. Heterogeneity in associations by race/ethnicity was tested using the Wald test of an AMPA-race/ethnicity cross-product term in the logistic model.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All tests were two sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study characteristics of breast cancer cases and controls are shown in Table 1. The largest racial/ethnic group among both cases and controls was Japanese Americans (n=65 cases, n=68 controls), followed by Whites (n=40 cases, n=39 controls), and Native Hawaiians (n=19 cases, n=19 controls). Cases were less likely than controls to have started menarche before 13 years old or to be parous; however, these differences were not statistically significant. The majority of participants were postmenopausal at baseline (81%) and reported no history of breast cancer among first degree female family members (86% cases, 83% controls). Almost all participants (97% cases, 96% controls) reported ever having a mammogram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Hawaii participants of the breast cancer nested case-control study in the Multiethnic Cohorta

| Cases (n=124) | Controls (n=126) | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)c | n (%)c | ||

| Age at urine collection, y | |||

| ≤64 | 58 (47) | 55 (44) | |

| 65–74 | 46 (37) | 54 (43) | |

| ≥75 | 20 (16) | 17 (14) | 0.62 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Japanese American | 65 (52) | 68 (54) | |

| White | 40 (32) | 39 (31) | |

| Native Hawaiian | 19 (15) | 19 (15) | 0.97 |

| Education | |||

| ≤High school graduate | 47 (38) | 57 (45) | |

| Some college | 30 (24) | 24 (19) | |

| College graduate | 21 (17) | 23 (18) | |

| Graduate school | 26 (21) | 22 (18) | 0.73 |

| Family history of breast cancer | |||

| No | 107 (86) | 105 (83) | |

| Yes | 16 (13) | 15 (12) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 6 (5) | 0.16 |

| BMI at urine collectiond | |||

| 18.5–24.9 | 74 (59) | 68 (55) | |

| 25–29.9 | 31 (25) | 36 (29) | |

| 30 or higher | 21 (17) | 20 (16) | 0.82 |

| Age at menarche, y | |||

| <13 | 59 (48) | 70 (56) | |

| 13–14 | 49 (40) | 43 (34) | |

| >14 | 16 (13) | 12 (10) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.41 |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 24 (19) | 24 (19) | |

| Post-menopausal | 100 (81) | 102 (81) | 0.95 |

| Age at first live birth, y | |||

| missing | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | |

| Nulliparous | 20 (16) | 13 (10) | |

| ≤20 | 21 (17) | 25 (20) | |

| 21–25 | 44 (36) | 45 (36) | |

| 26–30 | 29 (24) | 35 (28) | |

| ≥31 | 10 (8) | 5 (4) | 0.22 |

| Number of children | |||

| 0 | 20 (16) | 13 (10) | |

| 1 | 16 (13) | 15 (12) | |

| 2–3 | 70 (57) | 65 (52) | |

| ≥4 | 17 (14) | 32 (25) | |

| missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.18 |

| Hormone replacement therapy use | |||

| Never used | 45 (36) | 53 (42) | |

| Ever used | 79 (64) | 73 (58) | 0.35 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 73 (59) | 78 (62) | |

| Former smoker | 35 (28) | 38 (30) | |

| Current smoker | 16 (13) | 10 (8) | 0.44 |

| Alcohol intake, g/day | |||

| None | 67 (54) | 76 (60) | |

| <12 | 37 (30) | 35 (28) | |

| ≥12 | 19 (15) | 15 (12) | |

| missing | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.56 |

| Mammography screening | |||

| Never had a mammogram | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | |

| Ever had a mammogram | 120 (97) | 121 (96) | 0.75 |

Characteristics at baseline questionnaire, unless specified.

P-values are based on the chi-square test for categorical variables and on the t-test for continuous variables.

percentages may exceed 100 due to rounding

Body Mass Index, kg/m2.

The percentage of values above LLOQ was 90% and 84% among breast cancer cases and controls, respectively (Table 2). Geometric mean urinary AMPA excretion after creatinine-adjustment was nearly 40% higher among cases than controls (0.087 vs 0.063 ng AMPA/mg creatinine) after adjusting for race/ethnicity, age, and BMI, and there was higher AMPA excretion among the 65–74 y age group (0.086) compared to ≤64 y and ≥75 y age groups, (0.068 and 0.070, respectively, but these differences were not statistically significant. Overweight women (BMI 25.0–29.9) had non-significantly higher AMPA excretion (0.092), followed by normal-weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) and obese women (BMI≥30), (0.075 and 0.057, respectively). There were no differences in AMPA excretion by race/ethnicity after adjusting for age, BMI and case/control status.

Table 2.

Aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) excretion among Hawaii participants of the breast cancer nested case-control study in the Multiethnic Cohort

| Characteristic | n | Above LLOQa (%) |

Unadjusted geometric mean (ng AMPA/mg CREAb) | Adjusted geometric meanc (ng AMPA/mg CREAb) | 95% confidence interval (ng AMPA/mg CREAb) | p-valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All study participants | 250 | 87 | 0.074 | |||

| Breast cancer cases | 124 | 90 | 0.089 | 0.087 | 0.055 – 0.119 | 0.21 |

| Controls | 126 | 84 | 0.065 | 0.063 | 0.032 – 0.095 | reference |

| Age group: | ||||||

| 64 y or younger | 113 | 85 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.039 – 0.098 | reference |

| 65–74 y | 100 | 87 | 0.087 | 0.086 | 0.054 – 0.120 | 0.38 |

| 75 y or older | 37 | 95 | 0.074 | 0.070 | 0.019 – 0.123 | 0.95 |

| Race/ethnicity: | ||||||

| Japanese American | 133 | 84 | 0.075 | 0.072 | 0.041 – 0.104 | reference |

| Native Hawaiian | 38 | 92 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 0.027 – 0.127 | 0.91 |

| White | 79 | 90 | 0.078 | 0.076 | 0.041 – 0.111 | 0.88 |

| BMIe at urine collection | ||||||

| Under 25 | 142 | 87 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.045 – 0.105 | reference |

| 25 – 29.9 | 67 | 93 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.054 – 0.131 | 0.45 |

| 30 or higher | 41 | 78 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.010 – 0.107 | 0.53 |

lower limit of quantitation (0.001 ng/mL).

creatinine.

covariate-adjusted means, adjusted for all other factors in the table.

based on pairwise t-test comparing adjusted means for each category to that for the reference category.

body mass index (kg/m2).

Non-creatinine normalized urinary AMPA concentrations of our samples (<LLOQ to 3,698 ng/L) were within range found by others (Table 3).

Table 3.

Aminomethylphosphonic acid found in human urine

| n, Population | Country, sampling years | LLODa, LLOQb (ng/L) | Urine Concentration (ng/L) | % samples >LLOD, LLOQ | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 399 healthy adults | Germany, 2001–2005 | 100b | <LLOQ-1,880 | 15–60%d,e | [21] |

| 182, unknown population | 18 European countries, 2013 | 150b | <LLOQ-2,630 | 36% | [19] |

| 40 lactating women | USA, 2014–2015 | 30a, 100b | <LLOD-1,330 | 73% | [22] |

| 100 elderly healthy adults | USA, 1993–1996, 2014–2016 | 40a | cyears 1993–1996 114–222 years 1999–2000 205–384 years 2001–2002 185–339 years 2004–2005 164–290 years 2014–2016 319–482 | 5–71 %e | [20] |

| 250 mostly postmenopausal women | Hawaii, USA, 2001–2006 | 15a, 40b | <LLOQ-3,698 | 87% | current study |

lower limit of detection

lower limit of quantitation

taking into account only the amount of participants with levels above lower limit of detection

at or above LLOQ

varies by year

Compared to the lowest quintile of AMPA excretion, women in the second highest and the highest quintile had a statistically significantly higher risk of breast cancer (OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 1.02–9.03 and OR: 4.49; 95% CI: 1.46–13.77, respectively; p for trend=0.029; Table 4). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in association by race/ethnicity (pheterogeneity=0.55; data not shown).

Table 4.

Association between urinary aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) excretion and breast cancer risk among Hawaii breast cancer cases and their controls nested in the Multiethnic Cohorta

| AMPA quintileb | Cases | Controls | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPA (continuous)c | 123 | 123 | 3.49 | 0.35 | 34.51 | 0.286 |

| Quintile 1 [0.0005–0.0045] | 16 | 25 | 1 (ref) | |||

| Quintile 2 (0.0045–0.0276] | 27 | 24 | 2.59 | 0.93 | 7.17 | 0.068 |

| Quintile 3 (0.0276–0.0427] | 18 | 26 | 1.69 | 0.55 | 5.14 | 0.358 |

| Quintile 4 (0.0427–0.0758] | 25 | 23 | 3.03 | 1.02 | 9.03 | 0.047 |

| Quintile 5 (0.0758–3.698] | 37 | 25 | 4.49 | 1.46 | 13.77 | 0.009 |

| P for trendd | 0.029 | |||||

Modeled using conditional logistic regression with adjustment for body mass index at urine collection and for the following baseline factors: family history of breast cancer, age at menarche, age at first live birth, menopausal status, hormone replacement therapy use, smoking status, alcohol use, education, moderate to vigorous physical activity, ever having had a mammogram.

quintiles based on the controls.

Log-transformed AMPA levels. The number of cases and controls correspond to the complete matched sets (1 case, 1 control).

P-value for trend is based on the quintile medians.

Note: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively examine urinary excretion of AMPA, (a metabolite of the herbicide GLYP as well as of phosphonate-based detergents [9, 10]), and breast cancer risk in a population of predominantly postmenopausal women. While previous reports investigated breast cancer risk and pesticides exposure based entirely on self-reported information of pesticide exposure [30, 16, 31], our study objectively measured urinary AMPA concentrations by a state-of-the-art liquid chromatography mass spectrometry-based assay [26]. The preliminary results presented here suggest that increased AMPA exposure, as reflected by urinary AMPA excretion in overnight urine, may be associated with increased breast cancer risk.

In humans, GLYP is not known to be metabolized to AMPA or other products [15]. Thus, AMPA measured in urine samples of our population is likely due to direct AMPA exposure. We speculate exposure to have occurred through the diet and/or by drinking water contaminated with AMPA. This is a plausible theory owing to several studies that have detected GLYP and AMPA residues in numerous food and water sources (Figure 1) [32–36, 10, 37, 13].

Figure 1.

Sources leading to human exposure of aminomethylphosphonic acid

Following application, GLYP is absorbed by foliage then metabolized to AMPA within the plant or degraded mainly (70%) to AMPA by soil microbes [6, 7]. Our study participants were not explicitly asked about their current or previous residential GLYP application. Thus, we can only surmise that general GLYP use may have been a source for AMPA exposure in our population and that runoff from GLYP-treated areas reached surface or groundwater.

AMPA is also a key metabolite of phosphonate-based household laundry and cleaning detergents [9, 10]. Thus, contamination of the environment by these detergents could also be a source of AMPA exposure (Figure 1) if domestic wastewater entering wastewater treatment plants is re-used/recycled into drinking water. However, domestic wastewater in the State of Hawaii was not reused or recycled for drinking purposes between December 2001and May 2006, the period our samples were collected (personal communication with Sina Pruder, Engineering Program Manager, Hawaii Department of Health, Environmental Management Division Wastewater Branch). Thus, AMPA exposure from this source for our population is most likely negligible.

AMPA is a small compound (111 Daltons) [18], does not contain a phenolic structure, and is highly water soluble (5.8 g/L near 25°C) [18], which would suggest their non-persistence in humans. Thus, the fact that AMPA excretion was measurable (above the LLOQ), albeit at low levels, suggests that other compounds in the body may have additively or synergistically enhanced the bioaccumulation or persistence of AMPA, a common occurrence with EDCs and other environmental pollutants [5]. To date, studies investigating the endocrine-disrupting properties of GLYP are diverging and ongoing between independent investigators [38–40] and the European Food Safety Authority [41], while the endocrine-disrupting abilities of AMPA are unknown.

Unfortunately, the cross-sectional nature of and limited information available for this pilot study makes it difficult to ascertain the exact source of AMPA exposure in our participants. Moreover, the lag time between exposure and disease occurrence (in our breast cancer cases) creates further challenges in establishing causal relationships. Nonetheless, regardless of the source of AMPA, which remains inconsequential for our study purposes, the role of AMPA as a possible EDC and/or human carcinogen merits further study.

The urinary AMPA concentrations in our study, when expressed as ng/L, are within range of those found in the literature among supposedly non-occupationally exposed adults (Table 3). However, it is important to note that urinary analyte concentrations can vary widely depending on urine volume when urine specimens other than timed samples are utilized (only Conrad et al. [21] collected 24-hour urines). To adjust for dilution, urine samples are typically normalized by a urinalysis parameter. Creatinine is a non-protein bound breakdown product of muscle and protein metabolism, and the most commonly used normalization parameter because it is produced in the body at a fairly constant rate [42]. Aside from the fact that three of the studies listed in Table 3 were spot urine samples, a considerable percentage of samples were reported to contain AMPA (Table 3). It remains to be determined whether the extremely high percentage of detectable AMPA in our samples (87% overall; Table 3) is a result of the higher analytical sensitivity of our analysis method, higher exposure to AMPA in our multiethnic study population, other unknown factors, or a combination of these factors.

The relatively small sample size of our current study prohibits us from further speculation. We intend to analyze approximately 1800 more MEC samples to increase study power. With these additional 900 breast cancer cases and 900 controls, we will have 80% power to detect as significant the OR=1.4 or higher in the entire sample and OR=1.8 or higher within races/ethnicities. Thus, we will be able to examine racial/ethnic differences, along with other environmental exposures including BPA, phthalates, TCS, and paraben, and other risk factors.

Another limitation is the imputation of a fixed value for AMPA excretion below LLOQ; however, this did not affect our quintile model association results. Nonetheless, these limitations should not detract from the main findings of this study, which need to be further explored in a larger cohort study in the future.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively examine urinary AMPA excretion and breast cancer risk in a population of predominantly postmenopausal women. Our preliminary results suggest a potential association between AMPA exposure, as reflected by urinary AMPA excretion in overnight urine, and breast cancer risk. In our study, women with higher urinary AMPA excretion had a significantly increased risk of breast cancer compared to women with lower AMPA excretion. Analysis in a larger cohort is warranted to confirm our preliminary findings.

Highlights.

AMPA was detected in urine of 90% of cases, 84% of controls.

Breast cancer risk was 4.5-fold higher in the highest vs. the lowest AMPA quintile.

AMPA exposure may be associated with increased breast cancer risk.

Acknowledgement

We thank Drs. Anna Wu from the University of Southern California, and Iona Cheng from the University California, San Francisco for their helpful review of this manuscript. Dr. Wu is also acknowledged for initial data analysis that yielded similar results.

Funding:

This work was supported by the Hawaii Community Foundation (grant# 20ADVC-102165) and the National Cancer Institute (#P30 CA71789).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest/Competing interests: none

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Hawaii and the University of Southern California

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Availability of data and material: The data that support the reported findings of this study are available from AAF and XL.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Kohler BA, Sherman RL, Howlader N, Jemal A, Ryerson AB, Henry KA et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2011, Featuring Incidence of Breast Cancer Subtypes by Race/Ethnicity, Poverty, and State. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv048. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawaii Tumor Registry — University of Hawaii Hawaii Cancer at a Glance 2009–2013. 2016.

- 3.Vihko R, Apter D. Endogenous steroids in the pathophysiology of breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1989;9(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(89)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas DB. Do hormones cause breast cancer? Cancer. 1984;53(3 Suppl):595–604. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(4):293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duke SO. Glyphosate degradation in glyphosate-resistant and -susceptible crops and weeds. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(11):5835–41. doi: 10.1021/jf102704x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai SH, Ogbourne SM. Glyphosate: environmental contamination, toxicity and potential risks to human health via food contamination. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2016;23(19):18988–9001. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benbrook CM. How did the US EPA and IARC reach diametrically opposed conclusions on the genotoxicity of glyphosate-based herbicides? Environmental sciences Europe. 2019;31(1):2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaworska J, Van Genderen-Takken H, Hanstveit A, van de Plassche E, Feijtel T. Environmental risk assessment of phosphonates, used in domestic laundry and cleaning agents in The Netherlands. Chemosphere. 2002;47(6):655–65. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battaglin WA, Meyer M, Kuivila K, Dietze J. Glyphosate and its degradation product AMPA occur frequently and widely in US soils, surface water, groundwater, and precipitation. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 2014;50(2):275–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolpin DW, Thurman EM, Lee EA, Meyer MT, Furlong ET, Glassmeyer ST. Urban contributions of glyphosate and its degradate AMPA to streams in the United States. Sci Total Environ. 2006;354(2–3):191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medalie L, Baker NT, Shoda ME, Stone WW, Meyer MT, Stets EG et al. Influence of land use and region on glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid in streams in the USA. Sci Total Environ. 2020;707:136008. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aparicio VC, De Geronimo E, Marino D, Primost J, Carriquiriborde P, Costa JL. Environmental fate of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid in surface waters and soil of agricultural basins. Chemosphere. 2013;93(9):1866–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benbrook CM. Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environ Sci Eur. 2016;28(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12302-016-0070-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IARC. IARC monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risks to humans-volume 112: Some organophosphate insecticides and herbicides. Lyon, France: IARC, World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel LS, Werder E, Satagopan J, Blair A, Hoppin JA, Koutros S et al. Insecticide Use and Breast Cancer Risk among Farmers’ Wives in the Agricultural Health Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(9):097002. doi: 10.1289/ehp1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somasundaram L, Coats JR. Pesticide transformation products in the environment. Pesticide Transformation Products. 1991;459(1):2–9. doi: 10.1021/bk-1991-0459.ch001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunewald K, Schmidt W, Unger C, Hanschmann G. Behavior of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) in soils and water of reservoir Radeburg II catchment (Saxony/Germany). J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2001;164(1):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoppe HW. Determination of glyphosate residues in human urine samples from 18 European countries. Medical Laboratory Bremen, D-28357 Bremen/Germany. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills PJ, Kania-Korwel I, Fagan J, McEvoy LK, Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E. Excretion of the Herbicide Glyphosate in Older Adults Between 1993 and 2016. Jama. 2017;318(16):1610–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conrad A, Schroter-Kermani C, Hoppe HW, Ruther M, Pieper S, Kolossa-Gehring M. Glyphosate in German adults - Time trend (2001 to 2015) of human exposure to a widely used herbicide. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuire MK, McGuire MA, Price WJ, Shafii B, Carrothers JM, Lackey KA et al. Glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid are not detectable in human milk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(5):1285–90. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.126854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankin JH, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, Pike MC et al. A multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2000. February 15;151(4):346–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SY, Wilkens LR, Henning SM, Le Marchand L, Gao K, Goodman MT et al. Circulating fatty acids and prostate cancer risk in a nested case-control study: the Multiethnic Cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(2):211–23. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9236-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu AH, Franke AA, Tseng C, Wilkens LR, Conroy SM, Li Y et al. Exposure to Phthalates and Risk of Breast Cancer: the Multiethnic Cohort Study Breast Cancer Res 2021;under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Franke AA, Li X, Lai JF. Analysis of glyphosate, aminomethylphosphonic acid, and glufosinate from human urine by HRAM LC-MS. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2020;412(30):8313–24. doi: 10.1007/s00216-020-02966-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franke A, Halm B, Ashburn L. Isoflavones In Children and Adults Consuming Soy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;476:161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hiza HA, Kuczynski KJ et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(4):569–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duell EJ, Millikan RC, Savitz DA, Newman B, Smith JC, Schell MJ et al. A population-based case-control study of farming and breast cancer in North Carolina. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):523–31. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engel LS, Hill DA, Hoppin JA, Lubin JH, Lynch CF, Pierce J et al. Pesticide use and breast cancer risk among farmers’ wives in the agricultural health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(2):121–35. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duke SO, Rimando AM, Pace PF, Reddy KN, Smeda RJ. Isoflavone, glyphosate, and aminomethylphosphonic acid levels in seeds of glyphosate-treated, glyphosate-resistant soybean. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(1):340–4. doi: 10.1021/jf025908i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savini S, Bandini M, Sannino A. An Improved, Rapid, and Sensitive Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-High-Resolution Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry Analysis for the Determination of Highly Polar Pesticides and Contaminants in Processed Fruits and Vegetables. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67(9):2716–22. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cessna A, Darwent A, Kirkland K, Townley-Smith L, Harker K, Lefkovitch L. Residues of glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in wheat seed and foliage following preharvest applications. Can J Plant Sci. 1994;74(3):653–61. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cessna A, Darwent A, Townley-Smith L, Harker K, Kirkland K. Residues of glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in canola seed following preharvest applications. Can J Plant Sci. 2000;80(2):425–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen MX, Cao ZY, Jiang Y, Zhu ZW. Direct determination of glyphosate and its major metabolite, aminomethylphosphonic acid, in fruits and vegetables by mixed-mode hydrophilic interaction/weak anion-exchange liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2013;1272:90–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cessna A, Darwent A, Townley-Smith L, Harker K, Kirkland K. Residues of glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in field pea, barley and flax seed following preharvest applications. Can J Plant Sci. 2002;82(2):485–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasnier C, Dumont C, Benachour N, Clair E, Chagnon MC, Seralini GE. Glyphosate-based herbicides are toxic and endocrine disruptors in human cell lines. Toxicology. 2009;262(3):184–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thongprakaisang S, Thiantanawat A, Rangkadilok N, Suriyo T, Satayavivad J. Glyphosate induces human breast cancer cells growth via estrogen receptors. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;59:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manservisi F, Lesseur C, Panzacchi S, Mandrioli D, Falcioni L, Bua L et al. The Ramazzini Institute 13-week pilot study glyphosate-based herbicides administered at human-equivalent dose to Sprague Dawley rats: effects on development and endocrine system. Environ Health. 2019;18(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12940-019-0453-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Authority EFS. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the potential endocrine disrupting properties of glyphosate. EFSA Journal. 2017;15(9):e04979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alessio L, Berlin A, Dell’Orto A, Toffoletto F, Ghezzi I. Reliability of urinary creatinine as a parameter used to adjust values of urinary biological indicators. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1985;55(2):99–106. doi: 10.1007/bf00378371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]