Abstract

Background

The majority of ingested foreign bodies pass through the gastrointestinal tract smoothly, with less than 1% requiring surgery. Fish bone could perforate through the wall of stomach or duodenum and then migrate to other surrounding organs, like the pancreas and liver.

Case presentation

We report herein the case of a 67-year-old male who presented with sustained mild epigastric pain. Abdominal computed tomography revealed a linear, hyperdense, foreign body along the stomach wall and pancreatic neck. We made a final diagnosis of localized inflammation caused by a fish bone penetrating the posterior wall of the gastric antrum and migrating into the neck of the pancreas. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed firstly, but no foreign body was found. Hence, a laparoscopic surgery was performed. The foreign body was removed safely in one piece and was identified as a 3.2-cm-long fish bone. The patient was discharged from the hospital on the fifth day after surgery without any postoperative complications.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic surgery has proven to be a safe and effective way to remove an ingested fish bone embedded in the pancreas.

Keywords: Fish bone, Pancreatic neck, Laparoscopic surgery, Case report

Background

The ingestion of foreign bodies occurs commonly in clinical practice. The majority of ingested foreign bodies pass through the gastrointestinal tract smoothly, with approximately 10–20% of foreign bodies requiring an endoscopic procedure, and less than 1% requiring surgery [1]. Fish bone could perforate through the wall of stomach or duodenum and then migrate to other surrounding organs, like the pancreas and liver [2–6]. The penetration of fish bones into the pancreas is quite rare [3, 4]. Rapid diagnosis and prompt treatment are mandatory to improve the prognosis of this rare condition. A mortality rate of 10% has been reported because of missed or delayed diagnosis [7]. Thus, we herein report a case of laparoscopic removal of an ingested fish bone migration to the neck of pancreas.

Case presentation

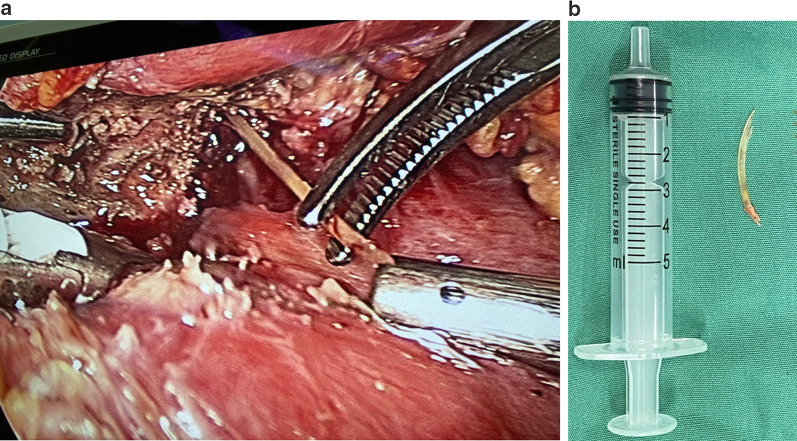

A 67-year-old male patient was admitted to the gastroenterology department due to abdominal pain over 3 months. He was hospitalized with a diagnosis of gastricism and a proton-pump inhibitor was started, but abdominal pain persisted. Physical examination showed mild epigastric tenderness. A complete blood count on admission were as follows: white blood count 9.76 × 109/L, the C-reactive protein level 138.31 mg/L, red blood count 3.79 × 1012/L, hemoglobin 120 g/L, platelets 118 × 109/L, liver function tests, kidney function tests and pancreatic enzyme levels were within normal limits. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was scheduled revealing a linear, hyperdense, foreign body along the stomach wall and pancreatic neck (Fig. 1a), and bone condition CT clearly shows the position and shape of the fish bone in the abdominal cavity (Fig. 1b). The patient was questioned about her past medical history. He remembered that he had abdominal pain after eating fish and something else 3 months ago. After urgent consultation, we made a final diagnosis of localized inflammation caused by a fish bone penetrating the posterior wall of the gastric antrum and migrating into the neck of the pancreas. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed; however, in addition to the chronic atrophic gastritis and distal gastric ulcer, no foreign body was found. Later, the patient was transferred to department of hepatobiliary and pancreatic oncology and underwent laparoscopic surgery. The patient was placed in a supine position. The operator stood on the right side of the patient, the assistant on the left side, and the scopist between the patient’s legs. Five trocars were placed: one above the navel for the laparoscopy (10 mm), two in the upper right abdominal quadrant (12 mm, 5 mm), and one in the upper left abdominal quadrant (10 mm, 5 mm). Fibrous structures were observed between the small curvature of the stomach and pancreas neck, and after the adhesions were dissected, a fish bone was identified and removed laparoscopically (Fig. 2a). The foreign body was identified as a 3.2-cm-long fish bone (Fig. 2b). Bleeding was controlled by pressure with a hemostatic gauze, and no suture repair was performed, because the penetrated wall was small and no leak was observed in both stomach and pancreas. Surgical intervention was completed after placing a drain in the operation area. The operation time is 2 h, and the bleeding during the operation is about 100 ml. Postoperative antibiotherapy was started, with proton-pump inhibitor treatment continuing for three more days. Clear fluid was drained, finally the drain pipe was removed on the third day after surgery. The patient was discharged from the hospital on the fifth day after surgery without any postoperative complications. And CT reexamination had not found obvious abnormality 2 months after the surgery.

Fig. 1.

a Computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed a linear, hyperdense, foreign body along the stomach wall and pancreatic neck. b The bone condition CT clearly shows the position and shape of the fish bone in the abdominal cavity

Fig. 2.

a A linear foreign body was found between the prepyloric region of the stomach and the pancreatic neck and was safely removed from both pancreas and stomach laparoscopically. b The foreign body was identified as a 3.2-cm-long fish bone after removal

Discussion

Sharp foreign bodies, like fish bones, chicken bones, sewing needles and tooth picks, may be ingested spontaneously [8, 9]. Having been reported in less than 1% of the cases, gastrointestinal perforation may cause peritonitis, localized abscess or inflammatory mass, bleeding or fistula [5, 10–13]. Fish bone is one of the most commonly ingested foreign bodies [14]. In most cases, a fish bone penetrated the stomach or the duodenum, but rarely migrated into the pancreas [3, 7, 15, 16]. This injury may be presented as a suppurative infection or pancreatic mass of the pancreas [12, 13].

Rapid diagnosis and early intervention of gastrointestinal foreign bodies are required to prevent morbidity and mortality [3, 4, 17]. Generally, patients are unable to provide a clear history of fish bone ingestion. Useful for detecting an ingested fish bone and its associated complications, CT usually reveals a linear, hyperdense, foreign body corresponding to a bone [18]. Since numerous foreign bodies migrate to the pancreas, surgical removal was quite effective in the management of an ingested foreign body when an endoscopic removal failed [3, 4, 6]. In addition, a laparoscopic approach may be more beneficial than open procedures because it allows the surgeon to approach the lesser sac with minimal manipulation of surrounding tissues under the help of optimal magnification and illumination [3, 19]. Recent years have witnessed more and more similar cases being addressed through laparoscopic surgery [3, 4, 6]. We refer to the English literature and found that only nine cases of an ingested fish bone that penetrated through the digestive tract and was embedded in the pancreas [3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 13, 15, 16, 20], as demonstrated in Table 1. Patients underwent laparoscopic surgery were found to recover faster. Compared with cases underwent open surgery, their postoperative day discharge was significantly shorter, as shown in Table 2. Therefore, laparoscopic approach should be preferred especially in this series, due to its advantages of less postoperative pain, lower incidence of wound infection, and minimal surgical stress [21].

Table 1.

Cases of an ingested fish bone that penetrated through the gastrointestinal tract and was embedded in the pancreas

| Reference number | Author | Year | Location | Duration of the onset to diagnosis (day) | Surgery | Fish bone length (cm) | POD discharge (day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Goh BK | 2004 | Stomach | 14 | Open | 2.8 | 11 |

| 12 | Wang WL | 2008 | Stomach | 28 | Open | 2.3 | 8 |

| 20 | Yasuda T | 2010 | Duodenum | 3 | Open | 4 | 14 |

| 16 | Symeonidis D | 2012 | Duodenum | 2 | Open | 3 | 7 |

| 7 | Huang YH | 2013 | Stomach | 1 | Open | 3.2 | 12 |

| 15 | Gharib SD | 2015 | Duodenum | 18 | Open | 3.7 | 11 |

| 3 | Kosuke Mima | 2018 | Stomach | 1 | Laparoscopic | 2.5 | 7 |

| 6 | Rui Xie | 2019 | Stomach | 5 | Laparoscopic | 3.5 | 7 |

| 4 | Francesk Mulita | 2020 | Stomach | 2 | Laparoscopic | 3 | 4 |

| – | Yang Wang | 2020 | Stomach | 90 | Laparoscopic | 3.2 | 5 |

POD postoperative day

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and surgical treatment outcomes of patients

| Characteristics | Total | Laparoscopic | Open |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) | (n = 4) | (n = 6) | |

| Year range of case report | 2004–2020 | 2018–2020 | 2004–2015 |

| Duration of the onset to diagnosis (days) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 16.4 ± 27.4 | 24.5 ± 43.7 | 11 ± 10.88 |

| Location | |||

| Stomach | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Duodenum | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Fish bone length (cm) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.12 ± 0.522 | 3.05 ± 0.42 | 3.167 ± 0.615 |

| POD discharge (days) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 8.6 ± 3.238 | 5.75 ± 1.5 | 10.50 ± 2.588 |

POD postoperative day

Conclusion

Our patient, after undergoing a laparoscopic removal of an ingested fish bone, recovered without complications. In short, laparoscopic surgery has proven to be a safe and effective way to remove an ingested fish bone embedded in the pancreas.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT

Computed tomography

Authors' contributions

We certify that all authors have participated sufficiently in the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Science and Technology Research Key Project of China (No. KJZD-K201900101).

Availability of data and materials

Data and material are available in this case report.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report has been approved by the appropriate ethics committee. The patient gave his informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

All the authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, Hafner M, Hartmann D, et al. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:489–496. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-100456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attila T, Mungan Z. Fish bone penetrating into the head of pancreas in a patient with Billroth II gastrojejunostomy. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2019;26:221–222. doi: 10.1159/000489720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mima K, Sugihara H, Kato R, Matsumoto C, Nomoto D, et al. Laparoscopic removal of an ingested fish bone that penetrated the stomach and was embedded in the pancreas: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2018;4:149. doi: 10.1186/s40792-018-0559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulita F, Papadopoulos G, Tsochatzis S, Kehagias I. Laparoscopic removal of an ingested fish bone from the head of the pancreas: case report and review of literature. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:123. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.123.23948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosar MN, Oruk I, Yazicioglu MB, Erol C, Cabuk B. Successful treatment of a hepatic abscess that formed secondary to fish bone penetration by laparoscopic removal of the foreign body: report of a case. Turk J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2014;20:392–394. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2014.31643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie R, Tuo BG, Wu HC. Unexplained abdominal pain due to a fish bone penetrating the gastric antrum and migrating into the neck of the pancreas: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:805–808. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i6.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang YH, Siao FY, Yen HH. Pre-operative diagnosis of pancreatic abscess from a penetrating fish bone. QJM. 2013;106:955–956. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guelfguat M, Kaplinskiy V, Reddy SH, DiPoce J. Clinical guidelines for imaging and reporting ingested foreign bodies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:37–53. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain A, Nag HH, Goel N, Gupta N, Agarwal AK. Laparoscopic removal of a needle from the pancreas. J Minim Access Surg. 2013;9:80–81. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.110968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crankson SJ. Hepatic foreign body in a child. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12:426–427. doi: 10.1007/BF01076958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ngan JH, Fok PJ, Lai EC, Branicki FJ, Wong J. A prospective study on fish bone ingestion. Experience of 358 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;211:459–462. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199004000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang WL, Liu KL, Wang HP. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Pancreatic abscess resulting from a fish bone penetration of the stomach. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1865–2160. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh BK, Jeyaraj PR, Chan HS, Ong HS, Agasthian T, et al. A case of fish bone perforation of the stomach mimicking a locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1935–1937. doi: 10.1007/s10620-004-9595-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HU. Oroesophageal fish bone foreign body. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:318–326. doi: 10.5946/ce.2016.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharib SD, Berger DL, Choy G, Huck AE. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 21–2015. A 37-year-old American man living in Vietnam, with fever and bacteremia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:174–183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1411439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Symeonidis D, Koukoulis G, Baloyiannis I, Rizos A, Mamaloudis I, et al. Ingested fish bone: an unusual mechanism of duodenal perforation and pancreatic trauma. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2012;2012:308510. doi: 10.1155/2012/308510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KF, Chu W, Wong SW, Lai PB. Hepatic abscess secondary to foreign body perforation of the stomach. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:297–300. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliashar R, Dano I, Dangoor E, Braverman I, Sichel JY. Computed tomography diagnosis of esophageal bone impaction: a prospective study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:708–710. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu C, Hungness ES. Laparoscopic removal of a pancreatic foreign body. JSLS. 2006;10:541–543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasuda T, Kawamura S, Shimada E, Okumura S. Fish bone penetration of the duodenum extending into the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:676–678. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dal F, Hatipoglu E, Teksoz S, Ertem M. Foreign body: a sewing needle migrating from the gastrointestinal tract to pancreas. Turk J Surg. 2018;34:256–258. doi: 10.5152/turkjsurg.2017.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and material are available in this case report.