Abstract

Background

Earlier studies suggest that probiotics have protective effects in the prevention of respiratory tract infections (RTIs). Whether such benefits apply to RTIs of viral origin and mechanisms supporting the effect remain unclear.

Aim

To determine the role of gut microbiota modulation on clinical and laboratory outcomes of viral RTIs.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of articles published in Embase and MEDLINE through 20 April 2020 to identify studies reporting the effect of gut microbiota modulation on viral RTIs in clinical studies and animal models. The incidence of viral RTIs, clinical manifestations, viral load and immunological outcomes was evaluated.

Results

We included 58 studies (9 randomized controlled trials; 49 animal studies). Six of eight clinical trials consisting of 726 patients showed that probiotics administration was associated with a reduced risk of viral RTIs. Most commonly used probiotics were Lactobacillus followed by Bifidobacterium and Lactococcus. In animal models, treatment with probiotics before viral challenge had beneficial effects against influenza virus infection by improving infection-induced survival (20/22 studies), mitigating symptoms (21/21 studies) and decreasing viral load (23/25 studies). Probiotics and commensal gut microbiota exerted their beneficial effects through strengthening host immunity.

Conclusion

Modulation of gut microbiota represents a promising approach against viral RTIs via host innate and adaptive immunity regulation. Further research should focus on next generation probiotics specific to viral types in prevention and treatment of emerging viral RTIs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00394-021-02519-x.

Keywords: Viral respiratory tract infections, Gut microbiota, Probiotics

Introduction

Viral respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are major global public health challenges because they are the most common causes of infectious diseases resulting in work and productivity loss [1, 2]. Effective antiviral drugs and vaccinations are lacking for non-influenza respiratory viruses [1, 3]. The outbreak of novel viruses causing high mortality, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2003, influenza A (H5N1) in 2005, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012, and influenza A (H7N9) in 2013 [4] and more recently, SARS-CoV-2 leading to novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in catastrophic outcomes. As of 30 Jan 2021, COVID-19 has infected over 102.6 million people and led to more than 2.2 million deaths worldwide. Given the challenges on both of the prevention and treatment of viral RTIs, it is important to identify effective and safe measures to protect against emerging infectious diseases.

Gut microbiota plays pivotal roles in establishing intestinal mucosal barrier function [5], shaping nutrient absorption and metabolism [6], and modulating host immunity [7]. Maintenance of microbiota homeostasis has been implicated to be crucial for creating colonization resistance to foreign pathogens [8]. Particularly, microbiota-mediated triggering, calibrating and functioning of both innate and adaptive immunity assist in facilitating protection against exogenous viruses [9, 10]. In contrast, a dysregulated microbiota composition which loses elasticity and diversity is more likely to provoke impaired immune responses [11].

Previous systematic reviews have identified the protective effects of oral probiotics and prebiotics in the prevention of RTIs [12–16]. However, very few studies included in these systematic reviews included virological tests whereas the majority studies defined RTIs according to subjective or indirect measures, such as self-reported symptoms, visits to general practitioners, antibiotics use, or even school loss, through which viral and non-viral infections were unable to be differentiated [12–16]. The effects of gut microbiota modulation on tackling viral RTIs remain unclear. Therefore, we performed a systematic review focusing on viral RTIs whereby etiologies were confirmed by virology tests.

The aims of this systematic review were to (i) determine the efficacy of gut microbiota modulation using probiotics on outcomes of viral RTIs in clinical studies; and (ii) delineate the role of probiotics and the importance of commensal gut microbiota in protecting the host against viral RTIs in animal models.

Methods

Search strategy

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [17]. An electronic literature search was performed on Embase and Ovid MEDLINE using the following keyword combinations: (‘virus’ or ‘Coronavirus’) and ‘infection’ and (‘microbiota’ or ‘microbiome’ or ‘probiotic’ or ‘prebiotic’ or ‘synbiotic’). The search was implemented without a starting date being applied but until 20 April 2020. The detailed searching strategy is provided in Additional file 1. Reference lists of original articles and relevant reviews were manually searched to identify additional studies for inclusion. After removal of duplicated references, initial screening of article titles and abstracts was undertaken by two independent investigators (HYS and XZ). Potential relevant articles were obtained in full text and reviewed independently. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and discussion with a third investigator (JWYM). Predefined criteria were used to determine eligibility for inclusion.

Selection criteria

We included interventional studies reporting the role of gut microbiota modulation on viral RTIs: (1) clinical studies on probiotics application in viral RTIs; (2) animal studies investigating the effects of gut microbiota manipulation on viral RTIs. Studies with clinical, virological, pathological or immunological outcomes were included. Studies were excluded if: (1) infecting organisms were not identified; (2) respiratory tract injury was caused by systemic viral infection (i.e. human immunodeficiency virus infection); (3) we were unable to separate viral RTIs from viral infections of other sites (i.e. gastrointestinal tract); (4) none of the outcomes (rate of RTIs, symptoms, viral load, respiratory pathology, virus-specific antibodies) were presented; (5) paper was published as conference abstract, review, letter, note, lecture, comment or editorial; (6) full texts were unavailable; (7) the paper was not in English language.

Data extraction

Two investigators (HYS and XZ) extracted data and entered it into a spreadsheet independently. A third investigator (WLL) evaluated the accuracy of this process. The collected data included the first author, country, study type, virus, subjects, sample size, age, sex, methodology of gut microbiota manipulation (details of strains used for intervention, administration form, administration dose, treatment duration, follow-up duration), outcomes and immune response.

Risk of bias assessment

All included clinical trials were independently assessed for bias using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions [18] by 2 investigators (HYS and XZ), with disagreements resolved by a third investigator (JWYM). Bias was assessed on selection (randomization, allocation concealment), performance (blinding of participants and personnel), detection (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition (incomplete outcome data), reporting (selective reporting), and other bias (e.g., funding).

Results

Study selection

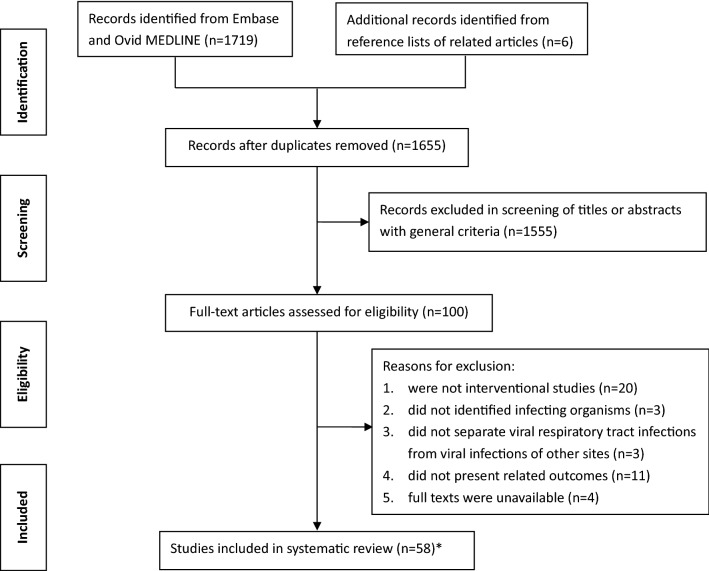

Overall, 1719 records were retrieved, and an additional six records were identified from reference lists of the related articles. After removal of 70 duplicates, 1655 records were screened according to the general criteria. Based on titles and abstracts, 1555 citations were rejected during the initial screen. Full texts of the remaining 100 articles were further reviewed for eligibility, and an additional 41 articles were excluded. Finally, our systematic review included 59 articles from 58 studies (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Literature search and selection of included studies in this systematic review. * Fifty-nine articles from 58 studies

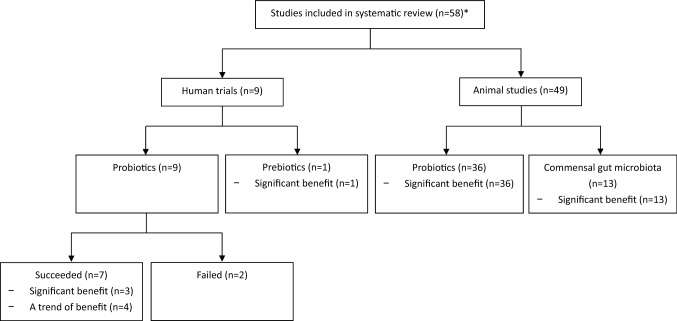

Fig. 2.

Categorization of included studies. * Fifty-nine articles from 58 studies

Human trials

Nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [19–28] involving 1240 healthy individuals assessed the efficacy of probiotics or prebiotics in preventing viral RTIs (Table 1). The nine trials reported the results of probiotics in individuals of different age groups: five [19, 20, 22, 24, 26, 27] focused on adults (n = 675), two [21, 28] on elderly subjects (n = 303), one on children [23] (n = 194) and one on preterm infants (n = 68) [25]. Lactobacillus was the most commonly used probiotics [19, 21–25, 27, 28], followed by Bifidobacterium [20, 24] and Lactococcus [26]. One trial also evaluated the efficacy of prebiotics (galacto-oligosaccharide and polydextrose) in preventing viral RTIs [25].

Table 1.

Clinical studies of probiotics and risk of viral RTIs

| First author, year of publication | Country | Participants | N/male:female | Infected virus | Virus inoculation | Probiotic(s); rebiotic(s) | Probiotic dose; prebiotic dose | Administration form | Treatment duration | Follow-up duration | Viral infection rate | Viral load | Symptom score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamamoto, 2019 [28] | Japan | Elderly | 107/33:74 | IFV | No | Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus | 1.8–3.5 × 1010 CFU/d | Yogurt beverage | 12wk | 12wk | – | – | – |

| Wang, 2018 [21] | Canada | Elderly | 196/64:132 | IFV, HRV, RSV, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza | No | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | 2 × 1010 CFU/d | Capsule | 6mo | 6mo | ↓ | – | – |

| Shida, 2017 [27] | Japan | Healthy adults | 96/96:0 | IFV | No | Lactobacillus casei Shirota | 1 × 1011 CFU/d | Milk formula | 12wk | 12wk | ↓ | – | – |

| Turner, 2017 [20] | United States | Healthy adults | 115/43:72 | HRV (28d after probiotic/placebo intervention) | Yes | Bifidobacterium animalis lactis | 2 × 109 CFU/d | Dissolved powder | 33d | 28d | ↓ | ↓* | NS |

| Tapiovaara, 2016 [19] | United States | Healthy adults | 59/21:38 | HRV (3w after probiotic/placebo intervention) | Yes | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | 1 × 109 CFU/d | Dissolved powder | 6wk | 3wk | - | ↓ | – |

| Kumpu, 2015 [22] | United States | Healthy adults | 59/21:38 | HRV (3w after probiotic/placebo intervention) | Yes | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | 1 × 109 CFU/d | Dissolved powder | 6wk | 3wk | ↓ | – | ↓ |

| Sugimura, 2015 [26] | Japan | Healthy adults | 213/92:121 | IFV | No | Lactococcus lactis | 1 × 1011 CFU/d | Yogurt beverage | 10wk | 10wk | NS | – | – |

| Lehtoranta, 2014 [24] | Finland | Healthy adults | 192/- | IFV, RSV, parainfluenza viruses, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, coronaviruses, picornaviruses, human bocavirus | No | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG; Bifidobacterium animalis lactis | 1 × 1010 CFU/d(L. rhamnosus); 4 × 109 CFU/d(B. lactis) | Chewing tablet | 90d/150d | 90d/150d | ↓* | – | – |

| Luoto, 2014 [25] | Finland | preterm infants (1–3d) | 68/44:24 | IFV, HRV, RSV, enteroviruses, adenovirus, coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, human enterovirus, human bocavirus | No | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG; polydextrose and galacto-oligosaccharides | 1 × 109 CFU/d(d1–d30), 2 × 109 CFU/d(d31–d60); 1 × 600 mg/d(d1–d30), 2 × 600 mg/d(d31–d60) | Milk formula | 57d | 12mo | ↓* | ↓(viral eradication time) | NS |

| Kumpu, 2013 [23] | Finland | children (2–6 Y/O) | 194/103:91 | IFV, HRV, RSV, parainfluenza virus, enterovirus, human bocavirus, adenovirus | No | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | 1 × 108 CFU/d | Milk formula | 28wk | 28wk | NS | – | NS |

IFV, influenza virus; HRV, human rhinovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; NS, no significant difference

*Significant difference

Effect of probiotics in reducing risk of infection

Of the eight studies with viral infection rate reported, the protective effects of probiotics in reducing the infection risk were noted in six studies [20–22, 24, 25, 27], although statistical significance was not observed in four of them [20–22, 27]. In a small study, there was less frequent occurance of picornaviruses (mainly rhinovirus) infection after three months of probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis BB-12) intake (5/13 vs. 15/17 of control group, p = 0.0069) among military recruits [24]. Another study found that among preterm infants, the rate of viral RTIs was reduced in infants with administration of probiotic (Lactobacillus rhamonosus GG) (52.4%) than those on placebo (83.3%) during a 12-month follow-up [25]. Frequent (> 3 episodes) viral RTIs were less commonly found in probiotic group (9.5%) than placebo group (33.3%). The risk of rhinovirus infection was decreased in probiotic group (rate ratio [RR] 0.49; p = 0.051), compared with placebo group. In sensitivity analysis assuming that missing subjects remained healthy throughout the study period, the incidence of rhinovirus-induced episodes was significantly lower in probiotic group, compared with that in placebo group (RR 0.43; p = 0.041).

Effect of probiotics on respiratory viral load

Three studies evaluated the impact of probiotics on viral load [19, 20, 25]. Two of these studies performed intranasal rhinovirus inoculation on healthy adults after 3 to 4 weeks of probiotics administration [19, 20]. The larger study with 115 subjects showed that pretreatment with 4 weeks of Bifidobacterium was associated with a significant reduction in nasal lavage virus titers (p = 0.03) and the proportion of subjects with virus shedding in nasal secretion was lower in the probiotic than placebo group (76% vs. 91%; p = 0.04) [20]. A separate small study showed a tendency towards a lower viral load in subjects pretreated with 3 weeks of Lactobacillus [19]. Among preterm infants, there were no significant differences on rhinovirus load between the Lactobacillus rhamonosus GG and placebo groups [25]. During symptomatic rhinovirus episodes, the median time for virus eradication was 10–15 days in the probiotic group, whereas it was more than 15 days in the placebo group, although the difference did not reach a statistical significance [25].

Effect of probiotics on clinical symptoms of viral infections

Four studies investigated the effect of probiotics on clinical symptoms caused by viral RTIs in a total of 441 subjects [20, 22, 23, 25]. One study showed a trend towards improved symptoms during the five days following rhinovirus inoculation in probiotic group [22], the overall results of the four studies failed to identify a significant protective effect of probiotics on alleviating the severity of viral infection-induced RTI symptoms.

Effect of prebiotics in the prevention of viral infections

Only one study investigated the effects of prebiotics (galacto-oligosaccharide and polydextrose) in the prevention of viral RTIs [25]. Among preterm infants, prebiotics significantly reduced the risk of viral RTIs (39.1% vs. 83.3%, p = 0.005) and frequent viral RTIs (0% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.005), compared with placebo during a 12-month follow-up. The incidence of rhinovirus infection was significantly lower in prebiotic group than that in placebo group (RR 0.31, p = 0.003). In sensitivity analysis, assuming that missing subjects remained healthy throughout the study period, the incidence of rhinovirus-induced episodes was significantly lower in prebiotic group, compared with placebo group (RR 0.29, p = 0.010). There was no significant difference on rhinovirus load between the prebiotic and placebo groups. Among symptomatic patients, the median time for virus eradication was shorter in the prebiotic group (10–15 days) than that (15 days) in the placebo group, although the difference did not reach a statistical significance. The severity of clinical symptoms was not significantly different between the prebiotic and placebo groups.

Risk of bias assessment

Summary of the risk of bias for the clinical studies was demonstrated in Table 2. There were 4 studies (5 articles) [19, 22, 23, 26, 27] at unclear risk for selection bias (did not describe the methods used to generate random sequence or conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient details). The risk of performance bias was high in one study [27] (lack of identical placebo). For 7 studies (8 articles) [19–25, 28], there was unclear risk of attribution bias (missing data on the main outcome, no formal sample size calculation or unmet predefined sample size). There were 7 studies (8 articles) [19, 21–23, 25–28] at unclear risk of other bias because the studies were funded by of the probiotic manufacturer or distributor, or the authors were employed by the provider of the study product.

Table 2.

Risk of bias summary for the randomized controlled trials in humans

| First author, year of publication | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamamoto, 2019 [28] | L | L | L | L | U | L | U |

| Wang, 2018 [21] | L | L | L | L | U | L | U |

| Shida, 2017 [27] | U | U | H | L | L | L | U |

| Turner, 2017 [20] | L | L | L | L | U | L | L |

| Tapiovaara, 2016 [19] | L | U | L | L | U | L | U |

| Kumpu, 2015 [22] | L | U | L | L | U | L | U |

| Sugimura, 2015 [26] | L | U | L | L | L | L | U |

| Lehtoranta, 2014 [24] | L | L | L | L | U | L | L |

| Luoto, 2014 [25] | L | L | L | L | U | L | U |

| Kumpu, 2013 [23] | L | U | L | L | U | L | U |

L, low risk; H, high risk; U, unclear risk

Animal studies

Probiotics and outcomes of viral RTIs in animal models

A total of 36 studies investigated the effects of oral administration of probiotics on outcomes of viral RTIs in animal models (Table 3). Probiotics were administered prior to viral infection in all of the studies. The majority of the studies (n = 28) used Lactobacillus [9, 29–55], followed by Bifidobacterium [56–58], Enterococcus [59–61] or Lactococcus [62, 63]. Thirty-one studies investigated the outcome of probiotics in influenza virus [9, 29, 32–49, 51–53, 55–61, 63], four studies targeted respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [30, 31, 36, 54], whilst the remaining studies focused on parainfluenza virus [62] and avian influenza virus [50].

Table 3.

Animal studies of probiotics and outcomes of viral RTIs

| First author, year of publication | Country | Infected virus | Animal | Probiotic(s) | Live/killed | Dose/concentration | Treatment time (before infection) | Intervention duration | FU duration | Mortality | Symptoms | Viral load | Severity of respiratory pathology | Viral-specific antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ermolenko, 2019 [60] | Russia | IFV | Mice | Enterococcus faecium | – | 1 × 107 CFU/d | 1d | 11d | 15d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | - | – | – |

| Mahooti, 2019 [58] | Iran | IFV | Mice | Bifidobacterium bifidum | – | 2 × 108 CFU | 21d | 21d (7 times) | 14d | ↓* | – | – | – | IgG↑* |

| Takahashi, 2019 [32] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus | Live | 1.14 × 108 CFU/d | 22d | 35d | 14d | NS | Weight loss:↓* | NS | – |

IgA↑* IgG↑* |

| Belkacem, 2018 [29] | France | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus paracasei | – | 2 × 108 CFU/d | 7d | 17d | 9d | – | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | – | – | – |

| Park, 2018 [49] | Korea | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus plantarum | Heat-killed | 1 × 108 to 5 × 1012/g, 0.05 mg or 10 mg dose in 200μL/d | 14d | 28d | 14d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | – | – |

| Belkacem, 2017 [55] | France | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus paracasei | – | 2 × 108 CFU/d | 7d | 17d | 10d | – | weight loss:↓*; clinical scores:↑*# | ↓* | ↓* | – |

| Chen, 2017 [59] | Taiwan | IFV | Mice | Enterococcus faecalis | Live, heat-killed | 8.5 × 1010 CFU/kg/d | 12d | 12d | 10d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | ↓ | – |

| Song, 2016 [51] | Korea | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Live | 1 × 109 CFU/mL, 0.3 mL | 14d | 34d | 20d | ↓* | – | – | ↓* | – |

| Kawahara, 2015 [57] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Bifidobacterium longum | – | 2.0 × 109 CFU in 200uL/d | 14d | 17d | 12d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | ↓* | – |

| Kikuchi, 2014 [42] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus plantarum | Heat–killed | 120 mg LAB/d | 28d | 4w | 10d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | – | IgA: NS |

| Nakayama, 2014 [47] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus gasseri | – | 1.0 × 108, 1.0 × 109 or 1.6 × 109 CFU/d | 21d | 42d | 21d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | ↓ | – |

| Waki, 2014 [34] | New Zealand | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus brevis | Live, lyophilized | 1 × 109 CFU/d | 14d | 14d | 7d | – | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | – | – | IgA↑* |

| Zelaya, 2014 [36] | Japan | IFV, RSV | Mice | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | – | 108 cells/d | 5d | 5d | 5d | – | – | ↓* | – | – |

| Goto, 2013 [9] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus acidophilus | Live, heat–killed | 10 mg/d (live bacteria: 100 mg/mL, 4 × 1010 CFU/ml; heat–killed bacteria: 33 mg/mL) | 15d | 21d | 6d | NS | Weight loss:NS; symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | ↓* |

IgG↓* IgA: NS |

| Kechaou, 2013 [41] | France | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus plantarum | Live | 1.0 × 109 CFU/d | 10d | 24d | 14d | – | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | – | – |

| Kiso, 2013 [43] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus pentosus | Heat–killed | 10 mg/d (1010 cells in 200 mL buffer saline) | 21d | 5w | 2w | ↓* | – | NS | NS | – |

| Park, 2013 [48] | United States | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus plantarum | Live | 109 or 108 CFU in 200 uL/d | 10d | 24d | 14d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | – | – |

| Iwabuchi, 2012 [37] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus paracasei | Heat–killed | 1 mg/0.2 mL/d (1 mg contained 1.9 × 106 microorganisms) | 14d | 19d | 6d | ↓ | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | ↓* | – |

| Kawase, 2012 [39] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus gasseri | Heat-killed | 10 mg/d | 14d | 19d | 20d | – | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | ↓* | – |

| Kondoh, 2012 [61] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Enterococcus faecalis | Heat-killed | 15 mg/d | 7d | 27d | 21d | ↓* | – | – | ↓* | – |

| Maruo, 2012 [63] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactococcus lactis cremoris | – | 1.5–3.8 × 108 CFU/ml, 100uL/d | 8d | 12d | 14d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | – | – |

| Youn, 2012 [35] | Korea | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus spp. (L. rhamnosus, L. plantarum, L. fermentum, L. brevis) | Live, heat-killed | 108, 107, 106 or 105 CFU/d | 21d | 21d | 14d | ↓* | – | ↓* | – | – |

| Iwabuchi, 2011 [56] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Bifidobacterium longum | Live, lyophilized | 2.0 × 109 CFU/0.2 mL/d | 14d | 19d | 6d | ↓ | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | ↓* | – |

| Kawashima, 2011 [40] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus plantarum | Heat-killed | 0.011, 0.21 or 2.1 mg/d | 7d | 14d | 14d | – | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | – | IgA↑* |

| Kobayashi, 2011 [44] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus pentosus | Heat-killed | 0.2, 0.4, 2, or 10 mg/d | 21d | 3w | 2w | ↓* | – | ↓* | – |

IgA↑* IgG↑* |

| Nagai, 2011 [46] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus | – | Yogurt 0.4 mL/d (3.5 × 108 cfu/g of L. bulgaricus, 6.8 × 108 cfu/g of S. thermophilus and 20 ug of polysaccharides) | 21d | 27d | 21d | ↓* | – | ↓* | – |

IgA↑* IgG↑* |

| Takeda, 2011 [33] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus plantarum | Heat-killed | 20 mg, twice daily | 2d | 9d | 14d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | ↓ | – |

| Kawase, 2010 [38] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus gasseri | Lyophilized | 10 mg, in 200 μL/d | 14d | 19d | 20d | – | Weight loss:NS; symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | ↓* | – |

| Maeda, 2009 [45] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus plantarum | Heat-killed | 3 mg/kg/d, 15 mg/kg/d, 75 mg/kg/d or 100 mg/kg/d | 7d | 14d | 14d | ↓* | – | ↓* | – | – |

| Yasui, 2004 [53] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus casei Shirota | Live | 108 CFU/d, 5 times/week | before virus infection | 3w (17 times) | 17d | ↓* | Symptom scores:↓* | ↓* | – | – |

| Hori, 2002 [52] | Japan | IFV | Mice | Lactobacillus casei Shirota | Heat-killed | – | before virus infection | 4 m | 3d | – | – | ↓* | – | – |

| Eguchi, 2019 [30] | Japan | RSV | Mice | Lactobacillus gasseri | Live, heat-killed, lyophilized | 2 × 109 CFU/d | 21d | 25d | 4d | – | Weight loss:↓* | ↓* | – | – |

| Fujimura, 2014 [31] | United States | RSV | Mice | Lactobacillus johnsonii | live, heat-killed | 3.9 × 107 CFU/d | 7d | – | 8d | – | – | – | ↓* | – |

| Chiba, 2013 [54] | Japan | RSV | Mice | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | – | 108 cells/d | 5d | 5d | 5d | – | weight loss:↓* | ↓* | ↓* | – |

| Jounai, 2015 [62] | Japan | Parainfluenza | Mice | Lactococcus lactis | heat-killed | 1 mg/d | 14d | 29d | 15d | ↓* | Weight loss:↓*; symptom scores:↓* | – | ↓* | – |

| Poorbaghi, 2014 [50] | Iran | Avian influenza virus | Chicks | Lactobacillus acidophilus | – | Probiotic: 109 CFU, prebiotic: 0.1% | before virus infection | Probiotic: D1 and D17; prebiotic: 34d | 14d | – | – | ↓* | – | – |

IFV, influenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; NS, no significant difference

*Significant difference

#Clinical scores: high scores indicated improved symptoms (while lower scores indicated improved symptoms in other studies)

Probiotics improved outcomes of mice infected with influenza virus

Twenty-two studies reported the effect of probiotics on survival after virus challenge [9, 32, 33, 35, 37, 42–49, 51, 53, 56–61, 63]. Amongst the 22 studies, 20 showed decreased mortality rates [35, 37, 42, 46–49, 51, 53, 56–61, 63] or prolonged survival time [33, 43–45] in mice, which were given probiotics. Five studies revealed a dose-dependent manner of Lactobacillus in improving survival [35, 44, 45, 47, 49]. One study found that live Lactobacillus spp. were superior to the inactivated ones in increasing survival rate [35].

Twenty-one studies evaluated the impact of probiotics on infection-induced symptoms [9, 29, 32–34, 37–42, 47–49, 53, 55–57, 59, 60, 63]. Being the most commonly reported symptom, weight loss was significantly mitigated in mice treated with probiotics in 18 studies [29, 32–34, 37, 39–42, 47–49, 55–57, 59, 60, 63]. Eleven studies scaled the symptoms using clinical scores based on fur appearance, eyelid, behavior or other indices, such as breath and body temperature, and all of these studies demonstrated significant improvement in mice given probiotics [9, 29, 34, 37–39, 41, 53, 55–57].

Twenty-five studies investigated the effect of probiotics on influenza viral load. Virus titers were lower in 23 studies tested in lungs [9, 33, 35–42, 44, 45, 47–49, 55, 56, 59, 63], bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) [40, 46, 47, 57], and nasal washings [52, 53] of mice pretreated with Lactobacillus[9, 32, 33, 35–49, 52, 53, 55], Bifidobacterium [56, 57], Enterococcus [59] or Lactococcus [63]. A dose-dependent manner of Lactobacillus was also observed in suppressing viral replication in lungs [40, 44, 49].

Immune responses underlying the effects of probiotics on mice infected with influenza virus

Seventeen studies discussed the intimate involvement of immune cells in probiotic-mediated protection against influenza virus infection [27, 29, 31, 33, 39, 46, 48, 52, 53, 55, 57, 58, 62, 64–67]. In particular, studies reported increased natural killer (NK) cell activities [27, 39, 46, 52, 53, 57, 64, 67], or decreased infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils in BALF [33] upon probiotic administration. Meanwhile, two studies with Lactobacillus or Lactococcus administration dramatically increased the recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs) [29, 62].

Twelve studies reported the contribution of interferon-α/β (IFN-α/β) to immune defenses against viral infections triggered by probiotic administration [9, 26, 30, 34, 45, 54, 57, 62, 68–71]. Of these, studies regard to Lactobacillus [9, 30, 34, 45, 54], Lactococcus [26, 62], Bifidobacterium [57], or Enterococcus [71] administration showed increased production of either IFN-α or IFN-β. Sixteen studies addressed the alteration of IFN-γ in respiratory virus infected mice administered with probiotics [26, 33, 39, 48, 51, 52, 54–58, 69, 71–74]. There are 12 studies declared the increase of IFN-γ after administration of probiotic Lactobacillus [30, 32, 33, 39, 48, 51, 52, 54, 55], Bifidobacterium [57, 58], or Bifico [73] (a probiotic mixture consisting Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Enterococcus). Seven studies indicated the roles of TNF-α in assisting immune defense against influenza virus infection [33, 36, 45, 48, 51, 52, 57]. Only one study detected increased production of TNF-α by nasal lymphocytes with administration of Lactobacillus [52]. Conversely, 6 of the studies consistently reported decreased TNF-α level, with 4 of them were being administered with Lactobacillus [33, 48, 74], 2 of them with Enterococcus [61, 71], while one of them with Bifidobacterium [57].

Seventeen studies reported the roles of dominant interleukins (ILs) in protective immune responses [9, 29, 33, 36, 48, 51, 53–59, 61, 71, 73, 74]. Four studies demonstrated that administration of Lactobacillus led to immune regulatory responses by upregulating IL-10 [36, 54, 55, 74]. Eight of the studies reported decrease in IL-6 after administration of Lactobacillus [33, 48], Bifidobacterium [56–58], Enterococcus [59, 71], or Bifico [73]. More specifically, strain-specific effects were observed in animal studies conducted using Lactobacillus rhamnosus M21 and CRL1505, respectively [51, 54], as Lactobacillus rhamnosus M21 mainly induces IL-12 increase while Lactobacillus rhamnosus CRL1505 promotes secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.

Eight studies [9, 32, 34, 40, 42, 44, 46, 58] tested the levels of virus-specific antibodies. Five of them reported increased influenza virus-specific immunoglobulin A (IgA) levels in the BALF [34, 40, 44, 46], and immunoglobulin G (IgG) titers in BALF [40, 44, 46] and serum [40, 44, 58] were elevated in the probiotic (Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium) group, compared with non-probiotic group. Probiotic feeding stimulated not only the production of influenza virus-specific IgA and IgG titers, but also accelerate their neutralization activities in serum and BALF in mice treated with oseltamivir [32]. One study revealed a dose-dependent manner of probiotics in stimulating influenza virus-specific IgA and IgG production [44].

Probiotics improved outcomes of mice infected with RSV

All of the four studies [30, 31, 36, 54] focused on RSV infection showed that Lactobacillus protected mice against RSV infection with alleviated body weight loss [30, 54], suppressed pulmonary RSV load [30, 36, 54], and milder pathological changes in lungs [31, 54]. Live probiotics were superior to inactivated probiotics in reducing pulmonary histopathological inflammation [31].

Commensal gut microbiota and the outcomes of viral RTIs in animal models

A total of thirteen studies investigated the influence of commensal gut microbiota on the outcomes of viral RTIs in animal models (Table 4). Of these studies, ten focused on influenza virus [8, 65, 66, 68, 73, 75–79], and the remaining studies were on RSV [80], parainfluenza virus [64] and avian influenza virus [81].

Table 4.

Animal studies of commensal gut microbiota and the outcomes of viral RTIs

| First author, year of publication | Country | Infected virus | Animal | Reason cause micriobiota change | Dose/concentration | Time of treatment initiation | Intervention duration | FU duration | Weight loss | Mortality | Viral load/virus shedding | Severity of respiratory pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradley, 2019 [79] | UK | IFV | Mice | Antibiotics and FMT | ABX: ampicillin(100 mg), vancomycin(100 mg), metronidazole(100 mg), gentamicin(100 mg) in 100 mL water; FMT: 200ul (D2-D5 post ABX treatment) | ABX: after virus infection; FMT: after ABX treatment | 4wk (ABX) | – |

ABX:↑*, FMT:↓* |

ABX:↑* | ABX:↑* | |

| Fuglsang, 2018 [75] | Austrilia | IFV | Mice | Antibiotics | Ampicillin (0.5 mg/mL), gentamicin sulfate (0.5 mg/mL), metronidazole (0.5 mg/mL) | 2wk before virus infection | 2wk (ABX2), 3wk (ABX1) | 28d | ABX:↑* | – | ABX:↑* | – |

| Pang, 2018 [78] | China | IFV | Mice | Antibiotics | 0.30 g/kg/d | 14d before virus infection | 14d | 5d | – | – | ABX:↑* | ABX:↑* |

| Yitbarek, 2018 [76] | Canada | IFV | Chickens | Antibiotics | Vancomycin(5 mg/mL), neomycin(10 mg/mL), metronidazole(10 mg/mL), amphotericin B(0.1 mg/mL), twice daily, and ampicillin (1 g/L, continuously provided) | d0–d15 before virus infection | 15d | 14d | – | – | ABX:↑* | – |

| Yitbarek, 2018 [68] | Canada | IFV | Chickens | Antibiotics | ABX: Vancomycin(5 mg/mL), neomycin(10 mg/mL), metronidazole(10 mg/mL), amphotericin–B(0.1 mg/mL) 10 mL/kg, twice daily and ampicillin(1 g/L, continuously provided); probiotics: 109 CFU/d; FMT: 8 mg with 1 × 109 bacterial cells/d | ABX 12d and probiotics/FMT 4d before virus infection, ABX 16d before virus infection | 20d (ABX); 4d (probiotics or FMT) | 5d | – | – |

ABX:↑* Probiotics:↓* FMT:↓* |

– |

| Jiang, 2017 [77] | United States | IFV | Mice | Antibiotics and fungi | Fungi: 106 CFU/d; ABX: ampicillin(0.5 mg/mL), gentamicin(0.5 mg/mL), metronidazole(0.5 mg/mL), neomycin(0.5 mg/mL), vancomycin(0.25 mg/mL), fluconazole (0.5 mg/mL), mannan 10 mg every other day | Fungi: 17d before virus infection, mannan: every other day starting 1 day prior to virus infection | 14d (fungi) | 20d | – |

ABX:↑* Fungi:↓* |

– | – |

| Rosshart, 2017 [8] | United States | IFV | Mice | Ileocecal microbial communities | 0.1 mL-0.15 mL | d14, d15, d16 of pregnancy | 3d | 18d | GM:↓* | GM:↓* | GM:↓* | GM:↓* |

| Wu, 2013 [73] | China | IFV | Mice | Antibiotics and probiotic | ABX: neomycin sulfate(6 mg/d); probiotic: Bifico(3.06 mg/d) | ABX: d1–d8 before virus infection; probiotic: d9–d12 | 12d | – | – | – | – | ABX:↑*, probiotic:↓* |

| Abt, 2012 [65] | United States | IFV | Mice | Antibiotics | Ampicillin (0.5 mg/mL), gentamicin(0.5 mg/mL), metronidazole(0.5 mg/mL), neomycin(0.5 mg/mL), vancomycin(0.25 mg/mL) | 2–4wk before viral infection | 2–4wk + 12d | 12d | ABX:↑* | ABX:↑* | ABX:↑* | ABX:↑* |

| Ichinohe, 2011 [66] | United States | IFV | Mice | Antibiotics | Ampicillin(1 g/L), vancomycin(500 mg/L), neomycin sulfate(1 g/L), and metronidazole(1 g/L) | 4wk before virus infection | 6wk | 2wk | – | – | ABX:↑* | – |

| Lynch, 2018 [80] | Australia | RSV | Mice | Antibiotics | Vancomycin (0.25 g/L), neomycin (0.5 g/L), ampicillin (0.5 g/L), metronidazole (0.5 g/L) | d13 of embryonic | 6wk | – | ABX:↑* | – | NS | ABX:↑* (pDCΔ mice) |

| Grayson, 2018 [64] | United States | Paramyxoviral virus | Mice | Antibiotics | Streptomycin sulfate (0.5 g/250 mL) | 14d before virus infection and during virus infection | 14d | 15d | – | ABX:↑* | ABX:↓(viral clearence)* | – |

| Figueroa, 2020 [81] | France | Avian influenza virus | Antibiotics | Vancomycin(80 mg/kg), neomycin(300 mg/kg), metronidazole(200 mg/kg), ampicillin(200 mg/kg), colistin(24 mg/kg), amphotericin B(2 mg/kg) daily | 2wk before virus infection | 21d | 7d | – | – | ABX:↑* | NS |

IFV, influenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; ABX, antibiotics; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; GM, gut microbiota; NS, no significant difference

*significant difference

All of the ten studies focused on influenza virus demonstrated beneficial effects of commensal gut microbiota against viral infection [8, 65, 66, 68, 73, 75–79]. In one study, natural gut microbiota from wild mice protected the recipient laboratory mice against influenza virus infection, manifested as reductions in mortality, weight loss, lung viral titers and respiratory immune-mediated pathology [8]. Depletion of intestinal commensal bacteria resulted in increased mortality [65, 79], greater weight loss [65, 75, 79], higher virus load [65, 66, 68, 75, 76, 78, 79] and more severe inflammation in lungs [65, 73, 78] of animals encountering viral challenge. In particular, antibiotic treatment by either cocktail (ampicillin, gentamicin, metronidazole, neomycin, vancomycin) [65, 66] or single antibiotic neomycin [66] both reduced CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. On the contrary, restoration of gut microbiota by probiotics (Bifico) supplementation [73], fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) [79] or even commensal fungi (Candida albicans or Saccharomyces cerevisiae) colonization [77] was able to alleviate the severity of viral infection deteriorated by gut dysbiosis.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first systematic review to report the role of gut microbiota manipulation on the risk and outcomes of viral RTIs. We found that modulation of gut microbiota may prevent viral RTIs in humans. Animal studies showed that treatments with probiotics before viral challenge were effective in improving the outcomes of viral RTIs, in terms of reducing infection-induced mortality, mitigating symptoms, decreasing viral load and boosting host immunity against viral infection. Disturbance of gut microbiota deteriorated in viral RTIs, which could be reversed by microbiota restoration. Furthermore, we have provided a data-driven explanation on the mechanisms by which gut microbiota modulation could impact viral RTIs.

Probiotics have been widely used to normalize perturbed gut microbiota and confer health benefits on hosts [82]. To focus on viral infections, we only included studies with positive virological tests or specific respiratory virus inoculation. Among the 8 RCTs in humans reporting virus infection rate, 6 showed decreased rates of RTIs in the probiotic group, suggesting probiotics are potentially promising agents to prevent viral RTIs. However, heterogeneity in studies had hindered direct comparison of individual study. Although current clinical studies did not show a significantly milder viral-induced symptoms in subjects on probiotics, animal studies illustrated a protective effect of Lactobacillus [9, 29–49, 51–54], Bifidobacterium [56–58], Enterococcus [59–61] and Lactococcus [62, 63] in alleviating the severity of viral infections. Mechanistically, probiotics could elicit protective responses against viral RTIs by inducing cytokine/chemokine production which further engage immune cells to modulate antiviral immunity, strengthening mucosal barrier through increasing mucin and tight junction molecules, etc. [83]. Probiotic-induced IFN-γ have functions in regulating both innate and adaptive immunity, making it powerful in macrophages activation and wide-spectrum antiviral defenses [84]. Also, majority of probiotics strengthen host immunity by utilizing IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18 as immune-response mediators while producing IL-1α/β, IL-6, and TNFα as pro-inflammatory factors, which in parallel depicted a preventative cytokine signature for evaluating probiotics [33, 48, 54, 57, 61, 71]. For example, oral administration of Bifidobacterium longum MM-2 elicit NK cell activation through upregulating pulmonary expressions of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-12 and IL-18, which further result with anti-influenza virus responses [57], while Enterococcus faecalis FK-23 oral administration, which exhibited improved survival rate in mouse model challenged by influenza A virus, upregulated anti-inflammatory IL-10 in lung tissues [61]. Probiotic boosts adaptive immune response with increased production of viral-specific IgA and IgG which is beneficial in defending viral RTIs. Besides innate and adaptive immunity, gut microbiota metabolism regulates inflammation through specific commensal bacteria that consume non-digestible dietary fibers and generate metabolites short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs, notably acetate, propionate, as well as butyrate) engaging in favoring mucosal barrier functionalities [80, 85–87]. However, these studies are all based on animal models. The mechanisms of probiotics in human viral RTIs need further investigations.

Data from animal studies have been predictive for the outcomes in subsequent human studies using the same strains. Oral administration of Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus OLL1073R-1 significantly prolonged the survival, reduced weight loss, decreased viral load and increased the anti-influenza virus antibodies in mice [32, 46]. Evidence has shown that consuming yogurt fermented with Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus OLL1073R-1 may help prevent influenza A virus subtype H3N2 infection by increasing the production of H3N2-bound salivary IgA in the elderly [28]. Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis JCM5805-fed mice showed a drastic improvement in survival rate, alleviation of infection related symptoms, and reduction in lung histopathology scores in parainfluenza virus infection [62]. A RCT on healthy adults had shown that Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis JCM5805 intake significantly reduced the cumulative incidence days of major symptoms of an influenza-like illness [26]. Mice studies evidenced the effects of different Lactobacillus plantarum strains in improving the outcomes of influenza virus infection [33, 35, 40–42, 45, 48, 49]. Oral administration of heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 enhanced protection against influenza virus infection by stimulating type I interferon production in mice [45]. A RCT conducted in subjects with high psychological stress levels showed that the incidence of upper RTI symptoms was significantly lower in those treated with heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 [88]. The mechanistic read-outs observed in mice could also be reproduced in humans. However, the overall effects of probiotics were much clearer in the animal studies than in humans, which may be explained by the more heterogenous setting including differences in environmental and host factors that are known to influence the gut microbiome (e.g. diet, drugs, co-morbidities, follow-up duration, immune status, etc.) in human studies.

The effects of probiotics are influenced by multiplex factors. Probiotics confer a health benefit when administered in adequate amounts [82]. Lactobacillus rhamonosus GG was the first patented strain belonging to the genus Lactobacillus with a large number of research data as the basis for its use in combating against RTIs in humans [89]. For preventing viral RTIs, Lactobacillus rhamonosus GG at a daily dose of 109 CFU or above appeared to be effective in human trials [21, 22, 24, 25], whereas a dose of 108 CFU daily did not show a significantly positive role [23]. The administration of Lactobacillus spp. was shown to protect against influenza virus infection in a dose-dependent manner in mice [35, 40, 44, 45, 47, 49]. It had been reported that the incidence and severity of upper RTIs negatively correlated with the duration of heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 intake among healthy people [88]. Duration of probiotic treatment in the prevention of viral RTIs ranged from 33 days [20] to 28 weeks [23] in humans. However, due to scarcity of data and different types of formula used, we are unable to propose a minimal treatment dose and duration to ensure optimal outcome in fighting against viral RTIs at this stage. Although the overall safety profile of probiotics is satisfactory, it should be noted that probiotic use could be associated with a higher risk of infection and/or morbidity in vulnerable people [90]. There is an increasing interest in non-viable microorganism-inducible health benefits [91]. Animal studies demonstrated the beneficial effects of non-viable (mainly heat-inactivated) probiotics in viral RTIs [9, 33, 37, 39, 40, 42–45, 49, 52, 59, 61, 62], although their effects appeared to be inferior to the live ones [31, 35]. The effects of probiotics in eliciting cytokine profiles in human cells and stimulating host immune system against viral RTIs in mice are highly strain-specific [92]. Since the data of strains other than Lactobacillus rhamonosus GG were fairly limited in human studies, comparison of the strain-specific effects against viral RTIs in humans remains unavailable. Probiotic mixtures have been proved to be more effective than single-strain probiotics in inhibiting pathogen growth, due to an additive and more synergetic multispecies probiotic consortium [93]. Taking advantage of this finding, FMT, which transplants the great mixture of healthy gut ecosystem to recipients, represents the most powerful strategy of restoring a balanced gut microbiota [94]. However, potential risk of infections caused by undetected or unmonitored pathogens remains to be a major concern for its broad applications [93]. To overcome this problem, Petrof et al. developed a stool substitute consisting of 33 different purified intestinal bacteria isolated from a healthy donor, and successfully treated patients with antibiotic-resistant Clostridium difficile colitis [95]. Accelerated by massively parallel sequencing, our knowledge of the composition and function of the human gut microbiota has dramatically extended the range of organisms with potential health benefits. The next-generation probiotics, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides uniformis, have been identified to exert anti-inflammatory effects in animal models [93, 96].

Prebiotics are substrates selectively utilised by host micro-organisms conferring a health benefit [97]. RCTs had shown that the use of prebiotics in infants could reduce the risk of RTIs [25, 98–100]. Luoto et al. demonstrated that both probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamonosus GG) and prebiotics (galacto-oligosaccharides and polydextrose) resulted in fewer episodes of viral RTIs, compared with placebo [25]. It is interesting to note that prebiotics tended to perform better than the probiotic in this trial. One possible reason might be the pre-existence of bifidobacteria-dominated infant gut microbiota, which strengthens the effect of “bifidogenic” prebiotics [99, 101]. A study on mice model had shown that specific dietary prebiotic oligosaccaharides potentiated immune response against viral RTI102.

The gut-lung axis has been proposed in the pathogenesis of certain respiratory diseases [103]. Evidence has implied a gut-lung crosstalk in viral RTIs. Gut microbiota influences the susceptibility and severity of viral RTIs. Natural gut microbiota exhibiting more diverse microbiomes balanced systemic and local inflammatory responses upon lethal influenza virus challenge, resulting in higher survival rates and a milder disease course, compared with gut microbiota of laboratory mice from a restrictive environment [8]. Mice with depletion of commensal gut microbiota had significantly worse outcomes of viral RTIs [64, 65, 73, 75, 78, 79], which was reversed by restoration of gut microbiota with probiotics [73], FMT [79], and even commensal fungi colonization [77]. Clinical observational studies have also evidenced the importance of healthy gut microbiota in protecting against viral RTIs. Higher level of butyrate-producing gut bacteria significantly associated with less development of viral RTIs among kidney transplant recipients [104], and reduced risk of viral lower RTIs in patients post-allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [105]. In another study involving patients underwent allogeneic HSCT and had viral RTIs post transplantation, the number of antibiotic-days was associated with progression to lower respiratory tract disease [106]. On the other hand, viral RTIs lead to gut microbiota alteration. Both influenza virus and RSV infections result in significant changes of gut microbiota in mice [72, 107, 108]. Influenza virus infection also resulted in decreased levels of SCFAs (the metabolic output of the gut microbiota) in both of the gut and blood in mice [86]. Oral administration of acetate protected mice against RSV infection [87]. Supplementation of acetate reduced lung pathology and improved survival rates of mice with influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae superinfection [86].

COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, is a major public health crisis threatening the human world today. This novel coronavirus, along with the SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV, belongs to Betacoronavirus genus [109]. Although patients typically present with fever and respiratory symptoms, the viruses can also affect the digestive system [110, 111]. Studies have reported frequencies of diarrhea ranging from 2.0 to 35.6%, 13.8 to 73.3% and 11.5 to 32.0% among patients with COVID-19, SARS and MERS, respectively [110]. Gut microbial dysbiosis has been identified in COVID-19 patients, characterized by enrichment of opportunistic pathogens and depletion of beneficial commensals [112, 113]. Gut microbiota alterations associated with disease severity. The severity of COVID-19 was positively correlated with the baseline abundance of Coprobacillus, Clostridium ramosum, and Clostridium hathewayi, and inversely correlated with that of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (an anti-inflammatory bacterium) [112]. Subjects with gut dysbiosis, such as elderly, immune-compromised patients and patients with other co-morbidities, tend to have more severe disease and poorer outcomes of COVID-19 [114]. It implies that gut microbiota modulation could potentially reduce disease severity. Most of the studies on gut microbiota modulation against viral RTIs were carried out on influenza virus as a prophylactic strategy, and no major evidence was available on its protective effect towards COVID-19, the importance of probiotics supplementation in COVID-19 treatment has been emphasized in the guidance given from China’s National Health Commission [113]. However, not all probiotics are equivalent for efficacy [115]. A novel and more targeted approach to modulate gut microbiota as one of the therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 and its complications is much needed. In a recent study reported by d’Ettorre et al., among COVID-19 patients, oral administration of a probiotic mixture significantly reduced the risk of developing respiratory failure, and a trend towards reduced rates of mortality [116]. The Chinese University of Hong Kong team has developed an oral gut microbiota modulating formulation against COVID-19. In a pilot study, this formulation significantly improved clinical symptoms and reduced pro-inflammatory immune markers in COVID-19 patients [117]. Viral infections predispose patients to secondary bacterial infections, which often result in a more severe clinical course [118]. Empirical antibiotics are sometimes used for the management of viral infection when secondary bacterial infection is a concern. However, Zuo et al. revealed that antibiotics use led to further loss of salutary symbionts and exacerbation of gut dysbiosis in COVID-19 patients [112]. Animal studies have also proved the adverse influence of antibiotics in viral RTIs [64, 65, 79]. These results suggest clinicians to avoid unnecessary antibiotics use in the treatment of viral RTIs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, previous studies shed a light on the influence of gut microbiota on the occurrence and outcomes of viral RTIs. Gut microbiota modification presented a potential prophylactic and therapeutic avenue against viral RTIs through boosting immunity of hosts. However, research in this field is still in its infancy. High-quality clinical trials, translational studies and mechanism investigations are urgently needed. Unlike animal models, humans are highly heterogeneous in terms of diet, age, genetic background and gut microbiota configuration, and therefore may respond differently to the same intervention. With the development of new technologies, individualized gut microbiota modification will become available to address specific consumer needs and issues. Next-generation probiotics specific to viral strains and individualized conditions of the hosts may become a promising therapy in the prevention and treatment of viral RTIs in the near future.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BALF

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- FMT

Fecal microbiota transplantation

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- IFN

Interferon

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- IL

Interleukin

- MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- NK

Natural killer

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- RR

Rate ratio

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- RTIs

Respiratory tract infections

- SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SCFAs

Short-chain fatty acids

- Th1

T helper type 1

- Th2

T helper type 2

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

Authors' contributions

HYS, XZ and WLL developed the protocol; conducted database searches; retrieved the data; and wrote the manuscript. JWYM contributed to the protocol development; conducted database searches and literature screening; assisted in risk of bias assessment and manuscript preparation. SHW contributed to the consultation; assistance in protocol development and manuscript preparation. STZ (Zhu), SLG, FKLC and STZ (Zhang) contributed to the consultation; provided critical intellectual input in the study and manuscript. SCN contributed to the study concept and design; consultation; critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Beijing Nova Program (Z201100006820147); National Nature Science Foundation of China (81702960); Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z181100001718221); Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Youth Programme (QML20180102); Beijing Talents Fund (2017000021469G209); and InnoHK, The Government of Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Hai Yun Shi, Xi Zhu and Wei Lin Li share co-first authorship

References

- 1.Behzadi MA, Leyva-Grado VH. Overview of current therapeutics and novel candidates against influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1327. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Doorn HR, Yu H. Viral respiratory infections. Hunter's Trop Med Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/b978-0-323-55512-8.00033-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodama F, Nace DA, Jump RLP. Respiratory syncytial virus and other noninfluenza respiratory viruses in older adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):767–790. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beigel JH, Nam HH, Adams PL, Krafft A, Ince WL, El-Kamary SS, Sims AC. Advances in respiratory virus therapeutics—a meeting report from the 6th isirv Antiviral Group conference. Antiviral Res. 2019;167:45–67. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonini M, Lo Conte M, Sorini C, Falcone M. How the interplay between the commensal microbiota, gut barrier integrity, and mucosal immunity regulates brain autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1937. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489(7415):242–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, Taniguchi T, Takeda K, Hori S, Ivanov II, Umesaki Y, Itoh K, Honda K. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331(6015):337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosshart SP, Vassallo BG, Angeletti D, Hutchinson DS, Morgan AP, Takeda K, Hickman HD, McCulloch JA, Badger JH, Ajami NJ, Trinchieri G, Pardo-Manuel de Villena F, Yewdell JW, Rehermann B. Wild mouse gut microbiota promotes host fitness and improves disease resistance. Cell. 2017;171(5):1015–1028e1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goto H, Sagitani A, Ashida N, Kato S, Hirota T, Shinoda T, Yamamoto N. Anti-influenza virus effects of both live and non-live Lactobacillus acidophilus L-92 accompanied by the activation of innate immunity. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(10):1810–1818. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correa-Oliveira R, Fachi JL, Vieira A, Sato FT, Vinolo MA. Regulation of immune cell function by short-chain fatty acids. Clin Transl Immunol. 2016;5(4):e73. doi: 10.1038/cti.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehtoranta L, Pitkäranta A, Korpela R. Probiotics in respiratory virus infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;33(8):1289–1302. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2086-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King S, Glanville J, Sanders ME, Fitzgerald A, Varley D. Effectiveness of probiotics on the duration of illness in healthy children and adults who develop common acute respiratory infectious conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(1):41–54. doi: 10.1017/s0007114514000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao Q, Dong BR. Wu T (2015) Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD006895. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006895.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Li X, Ge T, Xiao Y, Liao Y, Cui Y, Zhang Y, Ho W, Yu G, Zhang T. Probiotics for prevention and treatment of respiratory tract infections in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(31):e4509. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000004509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan CKY, Tao J, Chan OS, Li HB, Pang H. Preventing respiratory tract infections by synbiotic interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr (Bethesda, Md) 2020 doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeroy KR, Northridge ME, Balcazar H, Greenberg MR, Landers SJ. Reporting guidelines and the American Journal of Public Health's adoption of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):780–784. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2011.300630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tapiovaara L, Kumpu M, Makivuokko H, Waris M, Korpela R, Pitkaranta A, Winther B. Human rhinovirus in experimental infection after peroral Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG consumption, a pilot study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(8):848–853. doi: 10.1002/alr.21748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner RB, Woodfolk JA, Borish L, Steinke JW, Patrie JT, Muehling LM, Lahtinen S, Lehtinen MJ. Effect of probiotic on innate inflammatory response and viral shedding in experimental rhinovirus infection—a randomised controlled trial. Benef Microbes. 2017;8(2):207–215. doi: 10.3920/BM2016.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang B, Hylwka T, Smieja M, Surrette M, Bowdish DME, Loeb M. Probiotics to prevent respiratory infections in nursing homes: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(7):1346–1352. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumpu M, Kekkonen RA, Korpela R, Tynkkynen S, Jarvenpaa S, Kautiainen H, Allen EK, Hendley JO, Pitkaranta A, Winther B. Effect of live and inactivated Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG on experimentally induced rhinovirus colds: randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Benef Microbes. 2015;6(5):631–639. doi: 10.3920/BM2014.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumpu M, Lehtoranta L, Roivainen M, Ronkko E, Ziegler T, Soderlund-Venermo M, Kautiainen H, Jarvenpaa S, Kekkonen R, Hatakka K, Korpela R, Pitkaranta A. The use of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and viral findings in the nasopharynx of children attending day care. J Med Virol. 2013;85(9):1632–1638. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehtoranta L, Kalima K, He L, Lappalainen M, Roivainen M, Narkio M, Makela M, Siitonen S, Korpela R, Pitkaranta A. Specific probiotics and virological findings in symptomatic conscripts attending military service in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2014;60(3):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luoto R, Ruuskanen O, Waris M, Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Prebiotic and probiotic supplementation prevents rhinovirus infections in preterm infants: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugimura T, Takahashi H, Jounai K, Ohshio K, Kanayama M, Tazumi K, Tanihata Y, Miura Y, Fujiwara D, Yamamoto N. Effects of oral intake of plasmacytoid dendritic cells-stimulative lactic acid bacterial strain on pathogenesis of influenza-like illness and immunological response to influenza virus. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(5):727–733. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515002408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shida K, Sato T, Iizuka R, Hoshi R, Watanabe O, Igarashi T, Miyazaki K, Nanno M, Ishikawa F. Daily intake of fermented milk with Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota reduces the incidence and duration of upper respiratory tract infections in healthy middle-aged office workers. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56(1):45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto Y, Saruta J, Takahashi T, To M, Shimizu T, Hayashi T, Morozumi T, Kubota N, Kamata Y, Makino S, Kano H, Hemmi J, Asami Y, Nagai T, Misawa K, Kato S, Tsukinoki K. Effect of ingesting yogurt fermented with Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus OLL1073R-1 on influenza virus-bound salivary IgA in elderly residents of nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Odontol Scand. 2019;77(7):517–524. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2019.1609697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belkacem N, Bourdet-Sicard R, Taha MK. Lactobacillus paracasei feeding improves the control of secondary experimental meningococcal infection in flu-infected mice. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eguchi K, Fujitani N, Nakagawa H, Miyazaki T. Prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection with probiotic lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4812. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39602-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujimura KE, Demoor T, Rauch M, Faruqi AA, Jang S, Johnson CC, Boushey HA, Zoratti E, Ownby D, Lukacs NW, Lynch SV. House dust exposure mediates gut microbiome Lactobacillus enrichment and airway immune defense against allergens and virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(2):805–810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310750111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi E, Sawabuchi T, Kimoto T, Sakai S, Kido H. Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus OLL1073R-1 feeding enhances humoral immune responses, which are suppressed by the antiviral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in influenza A virus-infected mice. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102(11):9559–9569. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda S, Takeshita M, Kikuchi Y, Dashnyam B, Kawahara S, Yoshida H, Watanabe W, Muguruma M, Kurokawa M. Efficacy of oral administration of heat-killed probiotics from Mongolian dairy products against influenza infection in mice: alleviation of influenza infection by its immunomodulatory activity through intestinal immunity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(12):1976–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waki N, Yajima N, Suganuma H, Buddle BM, Luo D, Heiser A, Zheng T. Oral administration of Lactobacillus brevis KB290 to mice alleviates clinical symptoms following influenza virus infection. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;58(1):87–93. doi: 10.1111/lam.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youn HN, Lee DH, Lee YN, Park JK, Yuk SS, Yang SY, Lee HJ, Woo SH, Kim HM, Lee JB, Park SY, Choi IS, Song CS. Intranasal administration of live Lactobacillus species facilitates protection against influenza virus infection in mice. Antiviral Res. 2012;93(1):138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelaya H, Tsukida K, Chiba E, Marranzino G, Alvarez S, Kitazawa H, Aguero G, Villena J. Immunobiotic lactobacilli reduce viral-associated pulmonary damage through the modulation of inflammation-coagulation interactions. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;19(1):161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwabuchi N, Yonezawa S, Odamaki T, Yaeshima T, Iwatsuki K, Xiao JZ. Immunomodulating and anti-infective effects of a novel strain of Lactobacillus paracasei that strongly induces interleukin-12. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;66(2):230–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawase M, He F, Kubota A, Harata G, Hiramatsu M. Oral administration of lactobacilli from human intestinal tract protects mice against influenza virus infection. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;51(1):6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawase M, He F, Kubota A, Yoda K, Miyazawa K, Hiramatsu M. Heat-killed Lactobacillus gasseri TMC0356 protects mice against influenza virus infection by stimulating gut and respiratory immune responses. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;64(2):280–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawashima T, Hayashi K, Kosaka A, Kawashima M, Igarashi T, Tsutsui H, Tsuji NM, Nishimura I, Hayashi T, Obata A. Lactobacillus plantarum strain YU from fermented foods activates Th1 and protective immune responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(12):2017–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kechaou N, Chain F, Gratadoux JJ, Blugeon S, Bertho N, Chevalier C, Le Goffic R, Courau S, Molimard P, Chatel JM, Langella P, Bermudez-Humaran LG. Identification of one novel candidate probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum strain active against influenza virus infection in mice by a large-scale screening. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(5):1491–1499. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03075-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kikuchi Y, Kunitoh-Asari A, Hayakawa K, Imai S, Kasuya K, Abe K, Adachi Y, Fukudome S, Takahashi Y, Hachimura S. Oral administration of Lactobacillus plantarum strain AYA enhances IgA secretion and provides survival protection against influenza virus infection in mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e86416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiso M, Takano R, Sakabe S, Katsura H, Shinya K, Uraki R, Watanabe S, Saito H, Toba M, Kohda N, Kawaoka Y. Protective efficacy of orally administered, heat-killed Lactobacillus pentosus b240 against influenza A virus. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1563. doi: 10.1038/srep01563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi N, Saito T, Uematsu T, Kishi K, Toba M, Kohda N, Suzuki T. Oral administration of heat-killed Lactobacillus pentosus strain b240 augments protection against influenza virus infection in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maeda N, Nakamura R, Hirose Y, Murosaki S, Yamamoto Y, Kase T, Yoshikai Y. Oral administration of heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 enhances protection against influenza virus infection by stimulation of type I interferon production in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(9):1122–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagai T, Makino S, Ikegami S, Itoh H, Yamada H. Effects of oral administration of yogurt fermented with Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus OLL1073R-1 and its exopolysaccharides against influenza virus infection in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(12):2246–2250. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakayama Y, Moriya T, Sakai F, Ikeda N, Shiozaki T, Hosoya T, Nakagawa H, Miyazaki T. Oral administration of Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 is effective for preventing influenza in mice. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4638. doi: 10.1038/srep04638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park MK, Ngo V, Kwon YM, Lee YT, Yoo S, Cho YH, Hong SM, Hwang HS, Ko EJ, Jung YJ, Moon DW, Jeong EJ, Kim MC, Lee YN, Jang JH, Oh JS, Kim CH, Kang SM. Lactobacillus plantarum DK119 as a probiotic confers protection against influenza virus by modulating innate immunity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e75368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park S, Kim JI, Bae JY, Yoo K, Kim H, Kim IH, Park MS, Lee I. Effects of heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum against influenza viruses in mice. J Microbiol. 2018;56(2):145–149. doi: 10.1007/s12275-018-7411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poorbaghi SL, Dadras H, Gheisari HR, Mosleh N, Firouzi S, Roohallazadeh H. Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus and inulin on faecal viral shedding and immunization against H9 N2 Avian influenza virus. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;116(3):667–676. doi: 10.1111/jam.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song JA, Kim HJ, Hong SK, Lee DH, Lee SW, Song CS, Kim KT, Choi IS, Lee JB, Park SY. Oral intake of Lactobacillus rhamnosus M21 enhances the survival rate of mice lethally infected with influenza virus. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hori T, Kiyoshima J, Shida K, Yasui H. Augmentation of cellular immunity and reduction of influenza virus titer in aged mice fed Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9(1):105–108. doi: 10.1128/cdli.9.1.105-108.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yasui H, Kiyoshima J, Hori T. Reduction of influenza virus titer and protection against influenza virus infection in infant mice fed Lactobacillus casei Shirota. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(4):675–679. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.4.675-679.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiba E, Tomosada Y, Vizoso-Pinto MG, Salva S, Takahashi T, Tsukida K, Kitazawa H, Alvarez S, Villena J. Immunobiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus improves resistance of infant mice against respiratory syncytial virus infection. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17(2):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belkacem N, Serafini N, Wheeler R, Derrien M, Boucinha L, Couesnon A, Cerf-Bensussan N, Gomperts Boneca I, Di Santo JP, Taha MK, Bourdet-Sicard R. Lactobacillus paracasei feeding improves immune control of influenza infection in mice. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwabuchi N, Xiao JZ, Yaeshima T, Iwatsuki K. Oral administration of Bifidobacterium longum ameliorates influenza virus infection in mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34(8):1352–1355. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawahara T, Takahashi T, Oishi K, Tanaka H, Masuda M, Takahashi S, Takano M, Kawakami T, Fukushima K, Kanazawa H, Suzuki T. Consecutive oral administration of Bifidobacterium longum MM-2 improves the defense system against influenza virus infection by enhancing natural killer cell activity in a murine model. Microbiol Immunol. 2015;59(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahooti M, Abdolalipour E, Salehzadeh A, Mohebbi SR, Gorji A, Ghaemi A. Immunomodulatory and prophylactic effects of Bifidobacterium bifidum probiotic strain on influenza infection in mice. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;35(6):91. doi: 10.1007/s11274-019-2667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen MF, Weng KF, Huang SY, Liu YC, Tseng SN, Ojcius DM, Shih SR. Pretreatment with a heat-killed probiotic modulates monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and reduces the pathogenicity of influenza and enterovirus 71 infections. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(1):215–227. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ermolenko EI, Desheva YA, Kolobov AA, Kotyleva MP, Sychev IA, Suvorov AN. Anti-influenza activity of enterocin b in vitro and protective effect of bacteriocinogenic enterococcal probiotic strain on influenza infection in mouse model. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2019;11(2):705–712. doi: 10.1007/s12602-018-9457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kondoh M, Fukada K, Fujikura D, Shimada T, Suzuki Y, Iwai A, Miyazaki T. Effect of water-soluble fraction from lysozyme-treated Enterococcus faecalis FK-23 on mortality caused by influenza A virus in mice. Viral Immunol. 2012;25(1):86–90. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jounai K, Sugimura T, Ohshio K, Fujiwara D. Oral administration of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis JCM5805 enhances lung immune response resulting in protection from murine parainfluenza virus infection. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maruo T, Gotoh Y, Nishimura H, Ohashi S, Toda T, Takahashi K. Oral administration of milk fermented with Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris FC protects mice against influenza virus infection. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2012;55(2):135–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2012.03270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grayson MH, Camarda LE, Hussain SA, Zemple SJ, Hayward M, Lam V, Hunter DA, Santoro JL, Rohlfing M, Cheung DS, Salzman NH. Intestinal microbiota disruption reduces regulatory T cells and increases respiratory viral infection mortality through increased IFNgamma production. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1587. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abt MC, Osborne LC, Monticelli LA, Doering TA, Alenghat T, Sonnenberg GF, Paley MA, Antenus M, Williams KL, Erikson J, Wherry EJ, Artis D. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2012;37(1):158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ichinohe T, Pang IK, Kumamoto Y, Peaper DR, Ho JH, Murray TS, Iwasaki A. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(13):5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Makino S, Ikegami S, Kume A, Horiuchi H, Sasaki H, Orii N. Reducing the risk of infection in the elderly by dietary intake of yoghurt fermented with Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus OLL1073R-1. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(7):998–1006. doi: 10.1017/S000711451000173X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yitbarek A, Taha-Abdelaziz K, Hodgins DC, Read L, Nagy E, Weese JS, Caswell JL, Parkinson J, Sharif S. Author correction: gut microbiota-mediated protection against influenza virus subtype H9N2 in chickens is associated with modulation of the innate responses. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16367. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Liu X, Chen F, Zuo K, Wu C, Yan Y, Chen W, Lin W, Xie Q. Avian influenza virus subtype H9N2 affects intestinal microbiota, barrier structure injury, and inflammatory intestinal disease in the chicken ileum. Viruses. 2018 doi: 10.3390/v10050270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fejer G, Drechsel L, Liese J, Schleicher U, Ruzsics Z, Imelli N, Greber UF, Keck S, Hildenbrand B, Krug A, Bogdan C, Freudenberg MA. Key role of splenic myeloid DCs in the IFN-alphabeta response to adenoviruses in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(11):e1000208. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Z, Chai W, Burwinkel M, Twardziok S, Wrede P, Palissa C, Esch B, Schmidt MF. Inhibitory influence of Enterococcus faecium on the propagation of swine influenza A virus in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Groves HT, Cuthbertson L, James P, Moffatt MF, Cox MJ, Tregoning JS. Respiratory disease following viral lung infection alters the murine gut microbiota. Front Immunol. 2018;9:182. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu S, Jiang ZY, Sun YF, Yu B, Chen J, Dai CQ, Wu XL, Tang XL, Chen XY. Microbiota regulates the TLR7 signaling pathway against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Curr Microbiol. 2013;67(4):414–422. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao X, Huang L, Zhu L, Mou C, Hou Q, Yu Q. Inhibition of H9N2 virus invasion into dendritic cells by the S-layer protein from L. acidophilus ATCC 4356. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:137. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fuglsang E, Pizzolla A, Krych L, Nielsen DS, Brooks AG, Frokiaer H, Reading PC. Changes in gut microbiota prior to influenza A virus infection do not affect immune responses in pups or juvenile mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:319. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]