Summary

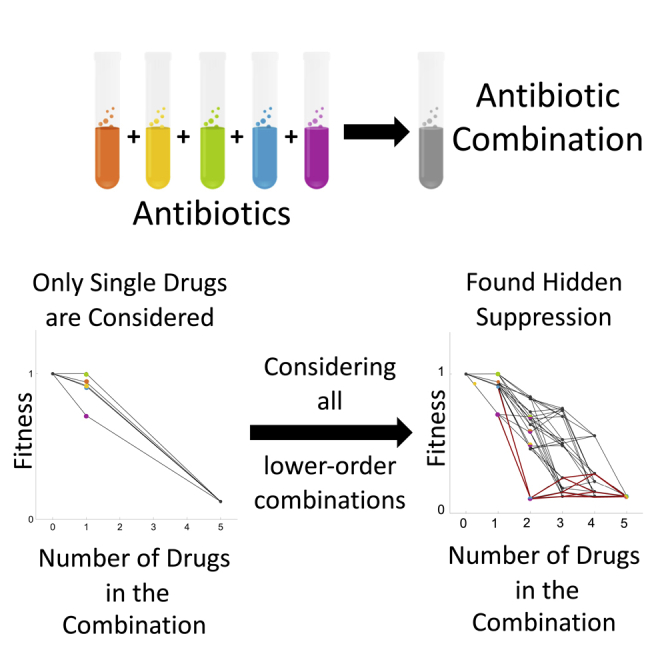

The rapid increase of multi-drug resistant bacteria has led to a greater emphasis on multi-drug combination treatments. However, some combinations can be suppressive—that is, bacteria grow faster in some drug combinations than when treated with a single drug. Typically, when studying interactions, the overall effect of the combination is only compared with the single-drug effects. However, doing so could miss “hidden” cases of suppression, which occur when the highest order is suppressive compared with a lower-order combination but not to a single drug. We examined an extensive dataset of 5-drug combinations and all lower-order—single, 2-, 3-, and 4-drug—combinations. We found that a majority of all combinations—54%—contain hidden suppression. Examining hidden interactions is critical to understanding the architecture of higher-order interactions and can substantially affect our understanding and predictions of the evolution of antibiotic resistance under multi-drug treatments.

Subject areas: Microbiology, Systems Biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Most instances of suppressive interactions are missed by standard methods

-

•

A majority (54%) of all antibiotic combinations tested contain hidden suppression

-

•

Identifying hidden suppression can affect what combinations should be used

Microbiology ; Systems Biology

Introduction

As the numbers of multi-drug resistant bacteria continue to increase globally (Bloom et al., 2018; Chokshi et al., 2019; Povolo and Ackermann, 2019), there has been a greater emphasis on multi-drug treatments (Fischbach, 2011; Rieg et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020). Two or more drugs interact in three main ways: additively, synergistically, or antagonistically. Additive combinations are when no interaction between drugs occurs; the combined effect is as expected, assuming each drug is acting independently (Bliss, 1939). A synergistic interaction occurs when two drugs work better than expected based on each single drug’s effects, resulting in decreased bacterial fitness. An antagonistic interaction occurs when two drugs are less effective at killing bacteria in combination than expected based on each single drug’s effects (Box 1).

Box 1. Definitions of important terms used.

Combination types

Higher-order combination: a drug combination of three or more drugs

Lower-order combination: a drug combination consisting of a smaller number of drugs that are included within a higher-order combination; in a 5-drug combination all combinations with four of those drugs, all combinations with three of those drugs, and all combinations of two of those drugs within the 5-drug combination are considered to be a lower-order combination to that specific 5-drug combination

Drug interactions

Additive interaction: no interaction between drugs; under Bliss independence, the combined effect is as expected assuming each drug is acting independently (Bliss, 1939)

Synergistic interaction: interaction between drugs is stronger than expected; drugs in combination are more effective at inhibiting growth than expected under the additive model

Antagonistic interaction: interaction between drugs is weaker than expected; drugs in combination are less effective at inhibiting growth than expected under the additive model

Suppressive interaction: interaction between drugs results in increased bacterial growth compared with the effects of fewer numbers of drugs; drugs in combination are not only less effective at inhibiting growth than expected under the additive model but also increases growth compared with lower-order combinations or single drugs

Net suppression: a suppressive interaction that occurs between the combination of drugs and the single-drug effects; there is greater bacterial growth when exposed to a drug combination than when exposed to a single drug

Emergent suppression: a suppressive interaction that occurs solely because all drugs are present in the combination

Hidden suppression: a suppressive interaction that occurs between the combination of drugs and a lower-order combination

Other useful terms

Full-factorial: a dataset that examines higher-order combinations with all their possible lower-order combinations, single-drug effects, along with positive and negative controls. For example, the full-factorial dataset for a single 5-drug combination includes the effects of the 5-drug combination as well as all possible 4-, 3-, and 2-drug combinations of those five drugs, all single drugs, positive controls, and negative controls.

Structure: the way to describe where interactions (net and hidden) occur within a combination

Path: a unique heterarchical grouping containing one representative of each of all the lower-order combinations within the highest-order combination

Nesting: a special type of structure where suppressive interactions occur when an N-drug combination is suppressive to an (N-1)-drug combination and (N-1)-drug combination is suppressive to an (N-2)-drug combination, which is suppressive to an (N-3)-drug combination; this nesting can continue until you compare a 2-drug combination with a single drug.

The most extreme form of antagonism, termed suppression, occurs when bacterial growth increases with a combination of stressors rather than one single stressor alone (Yeh et al., 2006; Chait et al., 2007). This phenomenon was first described over a century ago when Fraser (1870) showed that two different toxins if administered by themselves would normally kill a rabbit but combined would keep the rabbit alive. Fraser termed this “physiological antidote” to indicate that this was not the result of a chemical interaction of the two toxins but rather an interaction of the two chemicals' effects on the physiology of the organism (Fraser, 1870, 1872a, 1872b).

However, for over a century, the idea of one drug being an antidote for another was mostly ignored. More recently, in the last decade and a half, there has been a renewed interest in this phenomenon of suppression (Yeh et al., 2006; Chait et al., 2007; Cokol et al., 2014; de Vos and Bollenbach, 2014; Bollenbach, 2015; Singh and Yeh, 2017; Lukačišin and Bollenbach, 2019; Tyers and Wright, 2019; Dean et al., 2020). Suppression was first defined in terms of antibiotic interactions when a systematic study of 2-drug interactions in 21 antibiotics was conducted, and approximately 10% of all interactions fell into the category of suppression (Yeh et al., 2006). Since then, there has been significant new work published on suppressive interactions and their effects on the evolution of resistance, their mechanisms, and their prevalence.

Multiple advances have been made in the conceptual and experimental tools used to identify drug interactions that have yielded intriguing results about suppressive interactions (Yeh et al., 2006; Toprak et al., 2013; Cokol et al., 2014; Tekin et al., 2016; Katzir et al., 2019; Lukačišin and Bollenbach, 2019). For example, suppressive interactions have been shown to favor wild type (i.e., drug-sensitive strains) over drug-resistant strains in direct competition in vitro. This suggests that suppressive drug combinations could be used to make levels of drug resistance lower in a bacteria population by decreasing the evolutionary fitness of high-resistant strains (Chait et al., 2007). Other studies have shown that suppressive drug combinations could both decrease the rate at which bacteria adapt and evolve resistance to drugs in combination (Hegreness et al., 2008), as well as decrease the likelihood that resistance evolves from spontaneous mutations (Michel et al., 2008). In addition, mechanisms of suppression are being elucidated. The first mechanism for suppression identified was the nonoptimal regulation of the ribosome, which drives the suppressive nature of protein and DNA synthesis inhibitors (Bollenbach et al., 2009). Chaperone deletions can also consistently promote suppressive interactions between chloramphenicol-nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim-mecillinam (Chevereau and Bollenbach, 2015).

Even with this renewed focus on suppression, there has been a bias against publishing antagonistic and suppressive interactions (Singh and Yeh, 2017). The few papers that have looked for suppressive interactions have found that the amount of suppression varied to some degree but is consistently present in a proportion of drug combinations screened. In drug pairs, the amount of suppression ranges from 5% to 17%. Yeh et al. (2006) reported 8% of the combinations were suppressive. Cokol et al. (2014) reported that 17% were found to be suppressive. This has been considered to be a conservative estimation because the dataset was initially created to identify synergistic combinations (Cokol et al., 2011). Beppler et al. (2017) reported 5% of the 2-drug combinations examined were suppressive. In studies examining higher-order (more than two) drug combinations, suppression rates varied, 3% was observed in Beppler et al. (2017) and 8% was observed in Tekin et al. (2018).

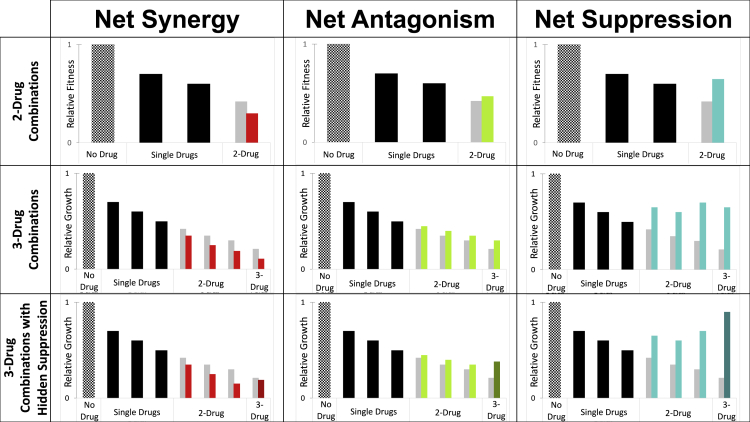

Suppressive interactions in 2-drug combinations are straightforward to identify: bacteria grow better in the presence of two drugs together compared with at least one of the single drugs (Figure 1). Suppressive interactions can also occur in higher-order drug combinations (Figure 1). For example, in a 5-drug combination, five drugs together could have less of an effect than four drugs, or they could have less of an effect than three drugs, two drugs, or a single drug. Also, a 4-drug subset from that five-drug combination could be suppressive to a 3-drug or 2-drug combination, or suppressive to a single drug.

Figure 1.

Antibiotic interactions in 2-drug and 3-drug combinations

Hatched bars represent growth in a no-drug environment; black bars represent the fitness of bacteria treated with a single antibiotic. Light gray bars represent the fitness of additive drug interactions, synergistic interactions are in red, antagonistic interactions are in green, and suppressive interactions are in teal. Note that the 2-drug combinations do not need to have the same net interaction type for a 3-drug combination to have a particular net interaction. Suppressive interactions are an extreme form of antagonism: notice that the bacteria treated with the suppressive drug combination has a higher fitness than the single drugs. Importantly, suppressive interactions can be hidden: this occurs when the highest-order combination has higher fitness than a lower-order combination but it does not have higher fitness than any of the single drugs. Thus, hidden suppression can only occur in a combination of 3 or more drugs. Also, note that bacteria treated with the 3-drug combination with hidden suppression has a higher fitness compared with any of the 2-drug combinations but not one of the single drugs.

Most studies examine interactions based on deviations from single-drug effects—termed “net suppression” (Box 1). This means the interaction of all the drugs in the combination is determined based only on the comparison with all the single-drug effects (Cokol et al., 2011; Stergiopoulou et al., 2011; Otto-Hanson et al., 2013; Tekin et al., 2017; Katzir et al., 2019). Some studies have also examined emergent interactions and have identified “emergent suppression” (Box 1) or that the effects only from all drugs being in combination are actually suppressive effects (Beppler et al., 2016, 2017; Tekin et al., 2016, 2017, 2018). In some instances, a suppressive interaction occurs due to suppression relative to a lower-order non-single-drug rather than a single drug; these interactions are termed “hidden” (Beppler et al., 2017; Tekin et al., 2018) (Figure 1). The term “hidden” is used because without examining the lower-order, non-single-drug effects we would never realize there was a suppressive effect (Beppler et al., 2017). For example, when examining a 3-drug combination's effect on bacteria, the interaction of the 3-drug combination is typically compared only with the single-drug effects. Often and not surprisingly, there is increased killing in the 3-drug combination compared with treatment with just one drug. However, the “hidden” part of the interaction comes from the fact that the 3-drug combination could do a worse job at killing bacteria than a subset using two of the three drugs (Figure 1, Box 1). Thus, the phenomenon of hidden interactions means that lower-order combinations are an important part of determining the interaction type of drug combinations.

Why do hidden interactions matter, and why does understanding the structure of these interactions matter? There are important consequences of interactions from both the basic science and the clinical perspectives. From an evolutionary perspective, interactions play an important role in the ecological and evolutionary trajectories of populations. Hidden suppressive interactions are typically not seen in a traditional examination of drug combinations. Considering these hidden interactions would substantially alter the topography of a fitness landscape.

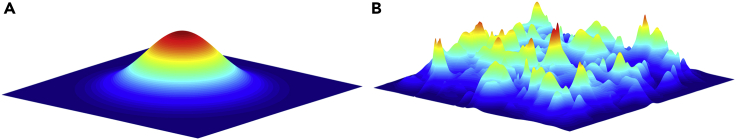

Fitness landscapes are the visualization of the relationships between factors such as stressors or genetic mutations and their effects on fitness (Wright, 1932, 1988). The highest peak in the fitness landscape is the most optimal combination for the bacteria to grow. Although multiple peaks may indicate that there are multiple good combinations of environments for the bacteria to grow, they also create valleys that can be difficult for populations to cross because an individual with intermediate traits or environments between peaks will face an overall decrease in fitness (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

An illustration of the fitness landscapes and the importance of ruggedness in evolutionary trajectories

(A) A smooth landscape only has one peak. As a population evolves to an environment there is always a path that leads to the optimum set of traits resulting in the highest possible fitness.

(B) In a rugged landscape, multiple peaks and valleys make evolving to the highest fitness not as straightforward as in a smooth landscape. Populations may have to cross a valley, which means (1) a loss of fitness must first occur before a net increase in fitness, (2) the population can become stuck at a local peak rather than evolve and ascend to the global peak, or (3) the population must make a jump from one peak to the next. Without the lower-order interactions, we may miss key details of intermediate peaks and valleys in the fitness landscape.

From a clinical perspective, using combinations that have hidden suppressive interactions could change the efficacy of a treatment: finding optimal combinations could be thrown off-course by hidden interactions. Understanding the structure and patterns of hidden interactions could therefore be important from both evolutionary and clinical perspectives.

However, studying hidden interactions has been difficult for two primary reasons: first, logistically, there has been substantial difficulty in obtaining full-factorial, higher-order drug interaction measurements. To obtain the full-factorial, growth measurements for all single and all lower-order subsets of drug combinations need to be determined. For example, the full-factorial for a single 5-drug combination includes one 5-drug combination, five 4-drug combinations, ten 3-drug combinations, ten 2-drug combinations, five single drugs alone, and a no-drug control. To obtain data from many full-factorial higher-order combinations has historically been challenging. Second, understanding conceptually and theoretically how to quantify interactions of higher-order drug combinations has been difficult. The logistic difficulty has been alleviated by automated robotics that can handle thousands of measurements in parallel, allowing focused questions that rely on large quantities of measurements. From the conceptual side, we can now accurately categorize the properties of the combination and the interactions, including emergent properties (such as emergent interactions and hidden suppression) (Beppler et al., 2016; Tekin et al., 2016, 2017, 2018). Emergent properties are only found in higher-order combinations and are solely because the combination is higher order, that is, the interaction occurs only due to all drugs combining and not due to lower-ordered combinations.

Here we propose a systematic examination of the structure of suppressive interactions (net, emergent, and hidden) in higher-order drug combinations. Specifically, we ask (1) how prevalent are hidden suppressive interactions? (2) What is the structure of a suppressive interaction: are they likely to be suppressive to the next lower-order combination? For example, do we primarily see a 5-drug combination that is suppressive relative to a 4-drug combination, or are there larger jumps in suppression, for example, a 5-drug combination that is suppressive relative to a 2-drug combination? Or is suppression likely to be nested—that is, if a 5-drug combination is suppressive, is it likely to be suppressive to 4-drug and 3-drug subsets within the 5-drug combination? (3) Lastly, are some antibiotics or main mechanism of actions more likely to be involved in general suppressive interactions?

Results

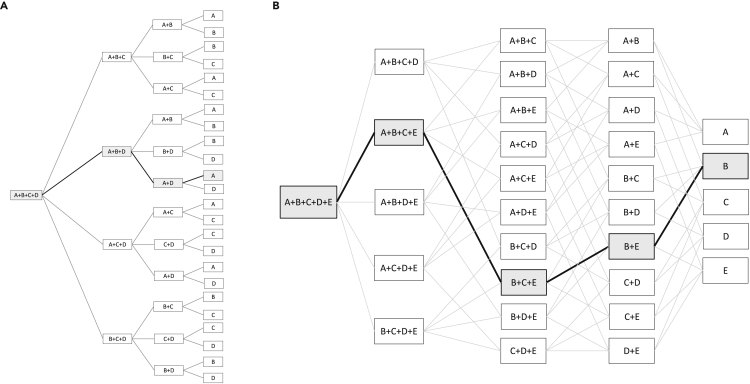

We re-examined the dataset collected and published in Tekin et al. (2018) to examine the presence and patterns of suppressive interactions (both hidden and net) within these combinations. A summary of methods used in Tekin et al. (2018) is provided in the Transparent methods section of the supplemental information. We compared the fitness of the highest-order interaction with all lower-order interactions, to determine if hidden suppression was present within the combination. This information was then examined through the use of paths. A path is a unique heterarchical grouping containing one representative of each of all the lower-order combinations within the highest-order combination (Figure 3). We use these paths to identify what suppressive interactions occur within a combination and to detect nesting of hidden suppression. That is, for example, “full” nesting occurs in a 5-drug combination when the 5-drug combination (A + B + C + D + E) is suppressive to a 4-drug combination (A + B + D + E) and that 4-drug combination is suppressive to a 3-drug combination (A + D + E), which is then suppressive to a 2-drug combination (A + D). Analyzing paths will enable us to understand the structure of the interactions—determining which comparisons between a specific lower-order combination and the highest-order combination are suppressive (Box 1). For a fuller description of the rationale behind the use of paths, please see the transparent methods section of the supplemental information. Please note that when referring to a single drug the full name of the antibiotic is written out, and when referring to a combination as a single entity the abbreviations of the drugs (Table 1) within the combination are used. For example, a combination containing the drugs ampicillin, fusidic acid, and streptomycin is listed as AMP + FUS + STR.

Figure 3.

The paths for a 4-drug and a 5-drug combination consisting of drugs A, B, C, D, and E

(A) All 24 possible paths are shown for a 4-drug combination.

(B) All 120 possible paths are shown for a 5-drug combination. For both the 4-drug (A) and 5-drug (B) combinations, a single path is shown in a bold line with the highest-order combination and each lower-order combination highlighted in gray. This single path represents a unique set of drugs, one at each level of combinations (4-drug, 3-drug, 2-drug, and a single drug), allowing for an assessment of any nesting. For this example, nested hidden suppression occurs when the 5-drug combination is suppressive to the 4-drug, the 4-drug combination is suppressive to a 3-drug combination, and the 3-drug combination is then suppressive to a 2-drug combination. And, if appropriate, the 2-drug combination is suppressive to the single-drug effects (this is only considered if the combination is net suppressive). If this is true for all paths the combination is considered to be fully nested. If this is only observed in some paths the combination is considered to be partially nested.

Table 1.

A list of the names, concentrations, main mechanism of action, mean relative growth compared with a no-drug control, and the abbreviation of the antibiotics used in this study

| Name (Abbreviation) | Main Mechanism of Action | Concentration () | Relative Growth (%) | Standard Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin (AMP) | Cell wall | 1–2.89 2–2.52 3–1.87 |

1–77.43 2–86.01 3–87.06 |

1–3.05 2–1.74 3–2.42 |

| Cefoxitin sodium salt (FOX) | Cell wall | 1–1.78 2–1.37 3–0.78 |

1–83.46 2–92.13 3–93.33 |

1–4.73 2–2.58 3–1.81 |

| Trimethoprim (TMP) | Folic acid biosynthesis | 1–0.22 2–0.15 3–0.07 |

1–79.59 2–74.63 3–68.20 |

1–3.89 2–4.26 3–3.93 |

| Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CPR) | DNA gyrase | 1–0.03 2–0.02 3–0.01 |

1–92.14 2–92.14 3–91.06 |

1–1.69 2–2.40 3–2.17 |

| Streptomycin (STR) | Aminoglycoside Ribosome, 30S |

1–19.04 2–16.6 3–12.25 |

1–81.10 2–90.77 3–83.53 |

1–6.50 2–1.37 3–4.30 |

| Doxycycline hyclate (DOX) | Ribosome, 50S | 1–0.35 2–0.27 3–0.15 |

1–75.15 2–76.53 3–70.01 |

1–5.51 2–5.13 3–4.73 |

| Erythromycin (ERY) | Ribosome, 50S | 1–16.62 2–8.29 3–1.78 |

1–84.25 2–84.29 3–79.63 |

1–5.77 2–5.60 3–5.91 |

| Fusidic acid sodium salt (FUS) | Ribosome, 30S | 1–94.42 2–71.01 3–37.85 |

1–82.31 2–78.82 3–82.62 |

1–2.51 2–2.83 3–2.47 |

The prevalence of hidden suppression

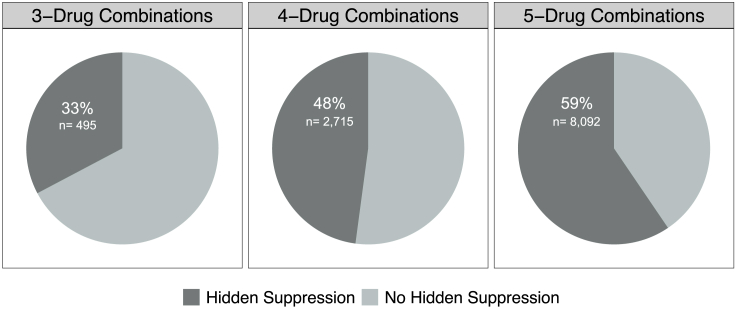

Nearly all higher-order combinations of unique drugs had at least one dose that produced a hidden suppressive interaction. Out of all the possible 182 higher-order drug combinations (fifty-six 3-drug combinations + seventy 4-drug combinations + fifty-six 5-drug combinations) only five (four 3-drug combinations and one 5-drug combination) had no unique dose that had hidden suppression: AMP + FUS + ERY, AMP + FOX + FUS, FOX + CRP + FUS, STR + FOX + FUS, and TMP + STR + FUS + DOX. Among all 20,790 of unique drug-dose combinations studied, suppressive interactions are observed in 54% (11,302) of combinations. With only 17% (3,534) of the total combinations identified as net suppressive (Tekin et al., 2018), the remaining 7,768 combinations with suppressive interactions only contain hidden suppressive interactions. By solely considering the highest-order combination and the single-drug effects, 69% of the combinations with suppressive interactions would not be identified (i.e., 7,768 out of 11,302). As the number of drugs in a unique drug dosage combination increases so does the percentage of combinations with hidden suppression: 33% of the 3-drug combinations, 48% of the 4-drug combinations, and 59% of the 5-drugs combinations had hidden suppression (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hidden suppression is present in a majority of higher-order combinations

Hidden suppression was found in all levels examined—3-drug, 4-drug, and 5-drug combinations. The amount of hidden suppression increases as the number of drug increases.

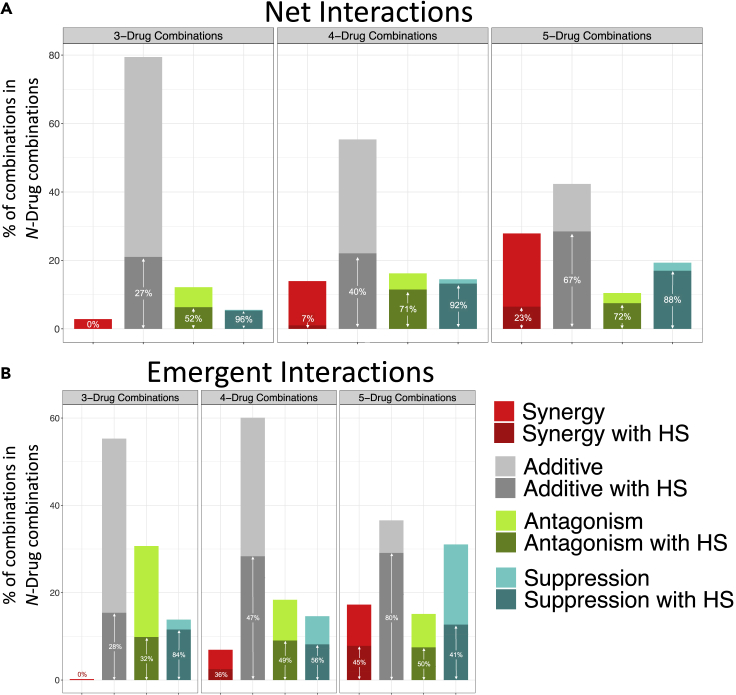

In cases where the net interaction is synergistic or additive, hidden suppression can still occur when the highest-order combination is compared with a lower-order combination (Figures 1, S1, and S2). Importantly, for a combination to contain hidden suppression, it is not dependent on the interaction type based on comparing the fitness values to the single drugs alone. For instance, a synergistic 4-drug combination that results in 20% relative fitness compared with no-drug environments can have a lower-order synergistic 2-drug combination that results in 10% relative fitness. This example then also has hidden suppression because the 4-drug combination results in more bacterial growth than the lower-order 2-drug combination but is still below the additive effects of the single drugs (Figure 1). Net additive combinations had hidden suppression in 27% of 3-drug combinations, 40% in 4-drug combinations, and 67% in 5-drug combinations (Figure 5). In net synergistic combinations, hidden suppression was found in 0% of 3-drug combinations, 7% of 4-drug combinations, and 23% in 5-drug combinations (Figure 5). Hidden suppression in net antagonistic combinations also increased as the number of drugs increased: 52% of 3-drug combinations, 71% of 4-drug combinations, and 72% in 5-drug combinations. In contrast, combinations that are net suppressive showed a decrease in the amount of hidden suppression as the number of drugs increased: 96% of 3-drug combinations, 92% of 4-drug combinations, and 88% in 5-drug combinations. These trends—the increase in the amounts of hidden suppression in synergistic, additive, and antagonistic with the increase in the number of drugs and the decrease in hidden suppression with the increase in the number of drugs among the suppressive interactions—are also observed when examining emergent interactions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The distributions and relative proportion of hidden suppression for each interaction type for net

(A) and emergent (B) interactions for 3-, 4-, and 5- drug combinations. The proportion of combinations with hidden suppression (HS) of suppressive interactions (teal) decreases as the number of drugs in a combination increases. The percentage written inside the darker shades of the bars represents the proportion of combinations with hidden suppression present in that specific interaction type. The y axis is the percentage of each interaction type within the designated level of the drug combination, showing the overall distribution of net or emergent interactions. For example, in (A) the net suppressive 4-drug combinations, 92% of the combinations have hidden suppression within them. As the number of drugs increases, the amount of hidden suppression within additive, synergistic, and antagonistic combinations also increase.

The structure of hidden suppression

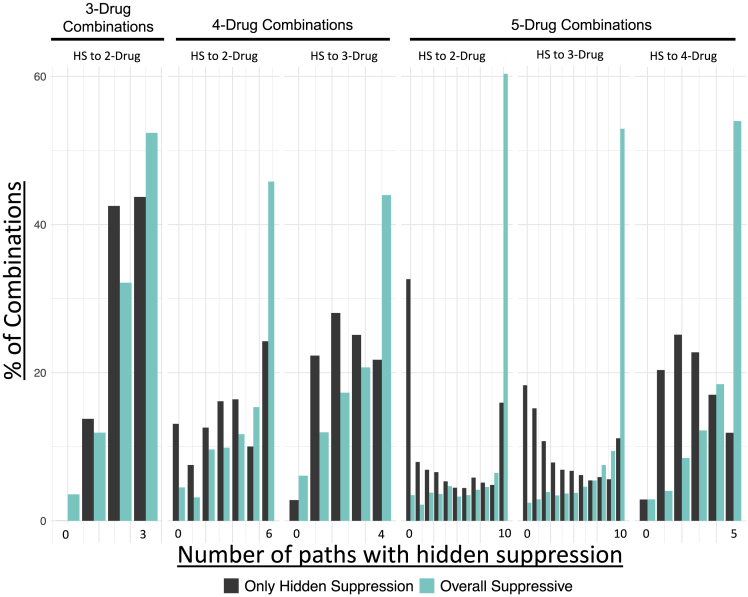

When addressing the structure of hidden suppression, it is important to recognize that in each drug combination multiple lower-order interactions are occurring. For example, in a 3-drug combination, there are three unique 2-drug combinations within it. Using the same framework, in a 5-drug combination there are ten unique 2-drug combinations, ten unique 3-drug combinations, and five unique 4-drug combinations. This results in a total of 25 possible hidden interactions. Combinations that contain hidden suppressive interactions can have suppressive interactions with one of the 25 possibilities, all of them, or any amount in between.

The highest-order combination has N drugs and is compared with all of the lower-order combinations to see where hidden suppression took place (Table 2). When comparing net suppressive combinations and those that only have hidden suppression, there are more instances of hidden suppression in combinations that are net suppressive no matter the number of drugs in the lower-order combination (Table 2, Figure 6). For example, in a 4-drug combination, there is suppression to the 3-drug combinations in 71% in net suppressive combinations, whereas in combinations with only hidden suppression it was only observed 60% of the time. Combinations that are net suppressive also have the highest amounts of hidden suppression occurring between all possible lower-order combinations (Figure 6). For example, in a 5-drug combination, there are a total of ten possible 2-drug combinations. In net suppressive 5-drug combinations, hidden suppression occurs between the highest-order combination and all possible 2-drug combinations roughly 60% of the time. This occurs in less than 20% of 5-drug combinations that only have hidden suppression. This trend, of hidden suppression being more common in net suppressive combinations than only hidden suppression combinations, can be observed no matter how many drugs are in the highest-order combination or the number of drugs in the lower-order combination it is being compared to. It also strengthens as the number of drugs in the highest-order combination increases. Figure 6 compares the amounts of hidden suppression in net suppressive combinations and only hidden suppression combinations. Overall, the difference between net suppressive combinations and only hidden suppression combinations is smaller in 3-drug combinations than in 5-drug combinations. This is especially true when observing if there is hidden suppression for all possible options of N-drugs in a lower-order combination.

Table 2.

Net suppressive combinations have more hidden suppression than combinations that are not net suppressive

| Hidden Suppression Found Between | Hidden Suppression Only (%) | Net Suppression (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Drugs versus 4-drugs | 53 | 80 |

| 5-Drugs versus 3-drugs | 41 | 79 |

| 5-Drugs versus 2-drugs | 40 | 80 |

| 4-Drugs versus 3-drugs | 60 | 71 |

| 4-Drugs versus 2-drugs | 61 | 75 |

| 3-Drugs versus 2-drugs | 76% | 77% |

Figure 6.

Hidden suppressive interactions occur more frequently within net suppressive combinations rather than within non-net suppressive combinations

The amounts of hidden suppression are shown out of the total number of lower-ordered combinations within a single higher-order combination that is either net suppressive (teal) or has some instances of hidden suppression (gray).

For net suppressive combinations, full nesting—when fitness at any order is greater than the fitness of the next lower-order combination in all paths including single-drug effects—was only observed in the 3-drug and 4-drug combinations. A majority of net suppressive combinations were considered to have net suppression, wherein at least one path, the fitness at any order must be greater than the fitness of all lower-orders (defined in the transparent methods, Table S1) (Figure S3). When examining the potential nesting of non-net suppressive combination, single-drug effects do not need to be considered because by definition there would be no suppression to the single drugs. All net synergistic combinations only contain hidden suppression that does not fall into any special case.

Likelihood of specific drugs or mechanisms of action involved in suppressive interactions

We used logistic regressions to determine if any drug or the main mechanism of action may have a positive association with general suppressive interactions (hidden and net). The presence of trimethoprim alone was found to be significantly positively associated with suppressive interactions for 3-drug, 4-drug, and 5-drug combinations (Tables 3, S2, and S6). Ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and erythromycin only had a significant positive association with suppressive interactions in 4-drug and 5-drug combinations (Tables S2 and S6). The presence of trimethoprim increased the odds of a 3-drug, 4-drug, and 5-drug combination being suppressive by roughly 2-fold (p < 0.001). The combined presence of ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim (CPR + TMP) and cefoxitin and trimethoprim (FOX + TMP) were also found to significantly increase the probability of finding suppressive interactions in 3-drug, 4-drug, and 5-drug combinations (p < 0.001) (Tables 4, S3, and S7). The combined presence of ampicillin and ciprofloxacin, ciprofloxacin and erythromycin, doxycycline and cefoxitin, and erythromycin and trimethoprim had a positive association with suppressive interactions for 4-drug and 5-drug combinations (p < 0.001) (Tables S3 and S7).

Table 3.

Logistic regression of a single drug with 3-drug combinations with some levels of suppressive interactions (hidden and net)

| Term | Coefficient | Confidence Interval |

p Value | Odds Ratio | Probability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.30% | 99.70% | |||||

| AMP | −0.416 | −0.720 | −0.117 | 1.58E-04 | 0.660 | 40 |

| CPR | 0.019 | −0.277 | 0.311 | 0.863 | 1.019 | 50 |

| DOX | 0.096 | −0.198 | 0.388 | 0.371 | 1.100 | 52 |

| ERY | −0.112 | −0.409 | 0.183 | 0.302 | 0.894 | 47 |

| FOX | −0.085 | −0.382 | 0.208 | 0.429 | 0.918 | 48 |

| FUS | −0.868 | −1.185 | −0.560 | 2.96E-14 | 0.420 | 30 |

| STR | −1.684 | −2.053 | −1.337 | 5.02E-38 | 0.186 | 16 |

| TMP | 0.729 | 0.443 | 1.018 | 3.75E-12 | 2.074 | 67 |

| AIC: 1678.2 | Bonferroni- corrected : 0.00625 | Degrees of Freedom: 1512 | ||||

Terms in bold have a significant positive association with suppressive interactions.

Table 4.

Logistic regression of pairwise drugs with 3-drug combinations with some levels of suppressive interactions (hidden and net)

| Term | Coefficient | Confidence Interval |

p Value | Odds Ratio | Probability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10% | 99.90% | |||||

| AMP + CPR | 0.126 | −0.576 | 0.817 | 0.571 | 1.134 | 53 |

| AMP + DOX | 0.252 | −0.379 | 0.877 | 0.208 | 1.287 | 56 |

| AMP + ERY | −0.778 | −1.498 | −0.097 | 4.95E-04 | 0.460 | 31 |

| AMP + FOX | −0.524 | −1.291 | 0.212 | 0.029 | 0.592 | 37 |

| AMP + FUS | −1.671 | −2.593 | −0.861 | 1.27E-09 | 0.188 | 16 |

| AMP + STR | −1.432 | −2.477 | −0.559 | 2.23E-06 | 0.239 | 19 |

| AMP + TMP | 0.953 | 0.305 | 1.627 | 6.08E-06 | 2.594 | 72 |

| CPR + DOX | 0.159 | −0.439 | 0.753 | 0.403 | 1.172 | 54 |

| CPR + ERY | −0.208 | −0.836 | 0.406 | 0.294 | 0.812 | 45 |

| CPR + FOX | −0.857 | −1.565 | −0.182 | 1.01E-04 | 0.425 | 30 |

| CPR + FUS | −0.307 | −1.008 | 0.359 | 0.159 | 0.736 | 42 |

| CPR + STR | −0.755 | −1.561 | −0.027 | 1.94E-03 | 0.470 | 32 |

| CPR + TMP | 0.739 | 0.122 | 1.379 | 2.25E-04 | 2.094 | 68 |

| DOX + ERY | −0.189 | −0.798 | 0.407 | 0.326 | 0.828 | 45 |

| DOX + FOX | 0.570 | −0.039 | 1.185 | 3.51E-03 | 1.768 | 64 |

| DOX + FUS | 0.388 | −0.238 | 1.002 | 0.050 | 1.474 | 60 |

| DOX + STR | −0.939 | −1.783 | −0.186 | 2.10E-04 | 0.391 | 28 |

| DOX + TMP | −1.044 | −1.685 | −0.420 | 2.31E-07 | 0.352 | 26 |

| ERY + FOX | 0.182 | −0.485 | 0.846 | 0.392 | 1.199 | 55 |

| ERY + FUS | −0.775 | −1.498 | −0.101 | 4.93E-04 | 0.461 | 32 |

| ERY + STR | 0.030 | −0.682 | 0.699 | 0.890 | 1.031 | 51 |

| ERY + TMP | 0.464 | −0.155 | 1.094 | 0.020 | 1.590 | 61 |

| FOX + FUS | −0.848 | −1.632 | −0.122 | 4.23E-04 | 0.428 | 30 |

| FOX + STR | −1.607 | −2.635 | −0.740 | 8.27E-08 | 0.201 | 17 |

| FOX + TMP | 1.026 | 0.387 | 1.698 | 9.05E-07 | 2.790 | 74 |

| FUS + STR | −0.942 | −1.924 | −0.104 | 1.06E-03 | 0.390 | 28 |

| FUS + TMP | −0.058 | −0.688 | 0.559 | 0.769 | 0.943 | 49 |

| STR + TMP | −0.978 | −1.756 | −0.259 | 4.08E-05 | 0.376 | 27 |

| AIC: 1579.7 | Bonferroni-corrected : 0.00179 | Degrees of Freedom: 1512 | ||||

Terms in bold have a significant positive association with suppressive interactions.

When considering the main mechanism of action rather than individual antibiotics, the presence of the antibiotic acting on folic acid biosynthesis (trimethoprim) was found to be significantly positively associated with suppressive interactions (p < 0.01) in 3-drug, 4-drug, and 5-drug combinations (Tables 5, S4, and S8). There were only two positive associations that occur across all levels of higher-order drug combinations (i.e., 3-drugs, 4-drug, and 5-drug combinations): they are with the antibiotic acting on folic acid biosynthesis, trimethoprim, alone (p < 0.0001) and the combination of two main mechanism of actions—folic acid biosynthesis and the DNA gyrase (p < 0.001) (Tables 6, S5, and S9). The probability of a combination having suppressive interactions decreases with the presence of an antibiotic acting on the 30S ribosomal subunit alone in the 3-drug, 4-drug, and 5-drug combinations (p < 0.0001) (Tables 5, S4, and S8).

Table 5.

Logistic regression of the main mechanism of actions with 3-drug combinations with some levels of suppressive interactions (hidden and net)

| Term | Coefficient | Confidence Interval |

p Value | Odds Ratio | Probability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50% | 99.50% | |||||

| Cell wall | −0.267 | −0.517 | −0.018 | 5.76E-03 | 0.765 | 43 |

| Folic acid biosynthesis | 0.742 | 0.470 | 1.017 | 2.74E-12 | 2.100 | 68 |

| DNA gyrase | 0.035 | −0.246 | 0.314 | 0.747 | 1.036 | 51 |

| Ribosome, 30S | −1.462 | −1.719 | −1.212 | 5.36E-50 | 0.232 | 19 |

| Ribosome, 50S | 0.062 | −0.188 | 0.312 | 0.524 | 1.064 | 52 |

| AIC: 1716 | Bonferroni-corrected : 0.01 | Degrees of Freedom: 1512 | ||||

Terms in bold have a significant positive association with suppressive interactions.

Table 6.

Logistic regression of the pairwise main mechanism of actions with 3-drug combinations with some levels of suppressive interactions (hidden and net)

| Term | Coefficient | Confidence Interval |

p Value | Odds Ratio | Probability (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.20% | 99.80% | ||||||

| Cell wall + folic acid biosynthesis | 1.016 | 0.548 | 1.495 | 5.52E-10 | 2.762 | 73 | |

| Cell wall + DNA gyrase | −0.417 | −0.949 | 0.096 | 0.021 | 0.659 | 40 | |

| Cell wall + ribosome, 30S | −1.565 | −2.050 | −1.109 | 6.46E-22 | 0.209 | 17 | |

| Cell wall + ribosome, 50S | 0.265 | −0.114 | 0.645 | 0.044 | 1.303 | 57 | |

| Folic acid biosynthesis + DNA gyrase | 0.742 | 0.175 | 1.326 | 1.90E-04 | 2.100 | 68 | |

| Folic acid biosynthesis + ribosome, 30S | −0.304 | −0.790 | 0.172 | 0.068 | 0.738 | 42 | |

| Folic acid biosynthesis + ribosome, 50S | −0.522 | −1.022 | −0.038 | 2.10E-03 | 0.593 | 37 | |

| DNA gyrase + ribosome, ribosome, 30S | −0.529 | −1.082 | −0.009 | 4.25E-03 | 0.589 | 37 | |

| DNA gyrase + ribosome, ribosome, 50S | −0.039 | −0.507 | 0.428 | 0.808 | 0.961 | 49 | |

| Ribosome, 30S + ribosome, 50S | −0.160 | −0.572 | 0.252 | 0.262 | 0.852 | 46 | |

| Cell wall + cell wall | −0.584 | −1.148 | −0.044 | 2.18E-03 | 0.558 | 36 | |

| Ribosome, 30S + ribosome, 30S | −1.565 | −2.411 | −0.857 | 3.93E-09 | 0.209 | 17 | |

| Ribosome, 50S + ribosome, 50S | −0.402 | −0.905 | 0.085 | 0.019 | 0.669 | 40 | |

| AIC: 1670.9 | Bonferroni-corrected : 0.0039 | Degrees of Freedom: 1512 | |||||

Terms in bold have a significant positive association with suppressive interactions.

Discussion

Although it was previously reported that higher-order drug combinations had a substantial amount of suppressive interactions (14% in Beppler et al. (2017) and 8% in Tekin et al. (2018)), there has been no further work on understanding the patterns and prevalence of higher-order suppressive interactions, particularly hidden interactions. The idea of hidden suppressive interactions was first introduced by Beppler and colleagues several years ago (Beppler et al., 2017). New technologies are now allowing rapid detection of suppressive interactions using both very small volumes of bacterial culture and antibiotic combinations (<1uL) and very short time frames of several hours (Cokol et al., 2011, 2014; Churski et al., 2012). New conceptual advances allow us to examine higher-order interactions and emergent properties of drug combinations (Beppler et al., 2016; Tekin et al., 2016; Katzir et al., 2019; Lukačišin and Bollenbach, 2019). Because of this, suppressive interactions have received more focus recently (see review Singh and Yeh (2017)). We have shown that even with recent advancements and interest in suppression, one can severely underestimate the number of suppressive interactions by not considering hidden suppression.

When examining hidden suppression, increasing the number of drugs in a combination also increases the number of possible lower-order combinations, thus possibly increasing the total number of combinations with hidden suppression interaction. When we look at the overall percentage of combinations with hidden suppression, this value steadily increases from 33% to 48%–59% as the number of drugs increases (Figure 4). This would explain the trends we see in Figure 5 for synergistic, additive, and antagonistic combinations. However, this does not offer a viable explanation for the negative correlation between the amount of hidden suppression and the number of drugs in a combination of net and emergent suppressive combinations.

In 2-drug combinations, it has been shown that a combination of DNA synthesis inhibitors and protein synthesis inhibitors has higher amounts of suppression (Yeh et al., 2006; Chait et al., 2007; Bollenbach et al., 2009). Thus, we expected that we might find some drugs or main mechanisms of actions more consistently involved in suppressive interactions, and this was indeed the case. We have shown that there is a significant positive association with suppressive interactions and interference with the 50S ribosomal subunit in combination with a DNA gyrase in 4-drug combinations and a significant positive association with suppressive interactions and interference with the 30S ribosomal subunit in combination with a DNA gyrase in 5-drug combinations. These findings are supported by the one suppressive mechanism that is very well understood (Bollenbach et al. (2009).

The main mechanism of action is one way that antibiotics are commonly grouped. We expected to see similar patterns of association between the logistic regressions based on specific drugs and the main mechanism of actions. We observe this similarity with the main mechanism of actions affecting folic acid biosynthesis trimethoprim, affecting the 50S ribosomal subunit—doxycycline and erythromycin and affecting DNA gyrase—ciprofloxacin. As previously described, the identification of DNA gyrases and protein synthesis can be expected to be positively associated with suppressive interactions. However, folic acid biosynthesis interference is positively associated with suppressive interactions in all levels of drug combinations (3-drug, 4-drug, and 5-drug combinations). We suggest that this cellular mechanism may also be a mechanism for suppression and could be a fruitful avenue for future studies.

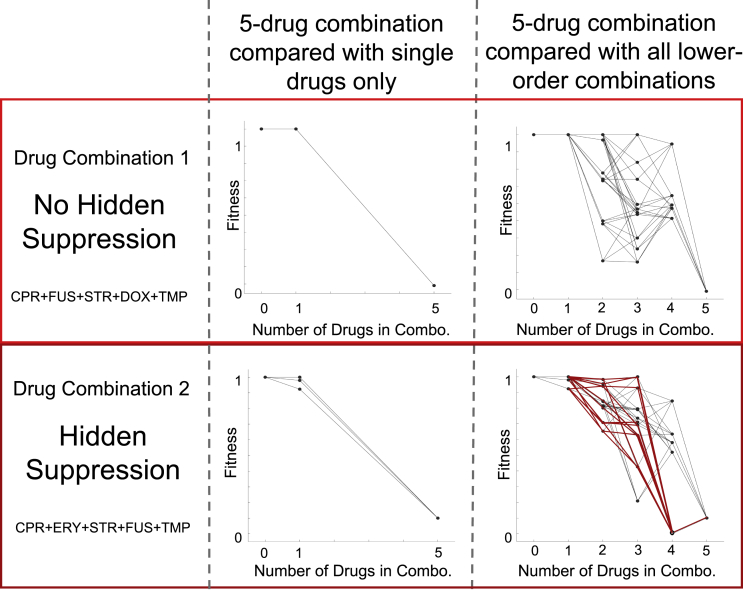

Hidden suppressive interactions can affect fitness landscapes, which means they ultimately could affect the evolutionary trajectory of populations. For example, if we use a drug combination with a corresponding fitness landscape based only on information from the single drugs and the 5-drug combination, we could end up with a landscape topography that looks very different from a fitness landscape where we had information from all lower-order drugs (Figure 7). This is not surprising because we have more information in the latter than the former. Qualitatively, the fitness landscapes are similar, but there are quantitative differences (Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al., 2019). In contrast, in cases where hidden suppression is present, a landscape without the lower-order interaction information would look very different from a landscape with all the lower-order interactions (Figures 7 and S4). Qualitatively, there are important differences between the fitness landscape because there are local valleys and peaks that are present in the latter and not present in the former. These valleys and peaks can affect how a population evolves and where it ends up (Østman et al., 2011; Palmer et al., 2015; Bendixsen et al., 2017).

Figure 7.

Fitness graphs show the importance of considering hidden interactions

Fitness graphs show similar information as a fitness landscape; they both help to visualize the relationships between stressors or genetic mutations and their effects on fitness. However, fitness graphs can be more appropriate for discrete data. Here we show fitness graphs of two synergistic 5-drug combinations (for abbreviations see Table 1). Drug combination 1 has no hidden suppression (top), and drug combination 2 has hidden suppression (bottom). The left-hand side shows the fitness graphs not considering the hidden suppression; notice how similar these two appear to be. Although the figures on the right-hand side show the fitness graphs including the lower-order combinations, notice the increase in ruggedness is due to the hidden suppressive interactions (the decrease in fitness at one of the 4-drug combinations) in the bottom right. The edges in red highlight the paths involved in hidden suppression. For more detailed information about these paths please see Figure S4.

Within a specific drug pair, recent work has shown that the concentrations at which two drugs veer into suppressive territory (from, for example, additivity) could be understood via a cost-benefit analysis. There is a trade-off between a drug inducing resistance (good for the bacterial cell) and increasing toxicity (bad for the bacterial cell), and this trade-off could explain why certain concentrations in one drug pair are suppressive, whereas other concentrations exhibit different interaction types (Wood and Cluzel, 2012). Furthermore, with some exceptions, suppressive interactions, as with most interactions, are typically robust to genetic mutations (Chevereau and Bollenbach, 2015).

Clinicians traditionally favor treatments with synergistic combinations, because it limits the number of antibiotics prescribed to the patient limiting any potential adverse effects (Lepper and Dowling, 1951; French et al., 1985; Sun et al., 2013; Arya et al., 2019), rather than treatment with suppressive combinations. This is because by definition, using suppressive interactions means using higher drug concentrations to achieve the same bacterial killing effect as drugs that are additive or synergistic. Thus, hidden suppressive interactions are ones that could be confounding in the clinic. As more treatments move to higher-order combinations of drugs (Mbuagbaw et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016; Morimoto et al., 2018; Tsigelny, 2019), it becomes critical to understand where suppressive interactions may be hidden, to avoid surprising and unwelcome clinical outcomes. For example, as shown in Figure 7, if one were to use a combination of CPR + ERY + STR + FUS + TMP and if we only compared the results of the five drugs together with all the single drugs alone, we would think this was a potentially useful combination, in that killing efficiency seems to increase relative to the five single drugs by themselves. But once we examine these in light of emergent properties, what we see is that CPR + ERY + STR + FUS + TMP has a lower killing efficiency than CPR + STR + FUS + TMP.

In conclusion, we show here that higher-order drug combinations exhibit a large number of suppressive interactions, and these interactions are primarily hidden. That is, we would never know there was a suppressive interaction if we only looked at the effects of the highest-order combinations and compared that with all the single-drug effects. Uncovering hidden suppressive interactions could decrease surprises regarding how populations evolve to drug combinations. At the same time, identifying hidden suppression can yield valuable information about underlying reasons regarding which drug combinations could be useful and which ones should be avoided.

Limitations of the study

Here we exemplify the need to consider hidden interactions and the possible implications of hidden suppression. To do this we examined an extensive dataset and found intriguing results. However, ideally, additional data could be analyzed with an even larger group of drugs examined, allowing for multiple representatives from each antibiotic class and the main mechanism of actions. The dataset from Tekin et al. (2018) used low levels of inhibition for each individual drug in an attempt to have detectable growth when antibiotics are used in 5-drug combinations. The low inhibition of each individual drug can affect the fraction of net-suppressive interactions by narrowing the range of a suppressive interaction. But ultimately these concentrations were chosen to avoid killing off the entire bacterial populations before a 5-drug combination could be examined. Finally, future studies of drug interactions can incorporate bootstrapping and other methods to determine robustness of results.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Dr. Pamela Yeh, PhD holds the role of lead contact and can be reached at pamelayeh@ucla.edu

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

All data and code has been made freely available via Mendeley Data (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ts2hnd72yf/1).

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicholas Ida, Austin Bullivant, and Nicholas Lozano for helpful comments that improved the manuscript. We are grateful for funding from the Hellman Foundation (P.J.Y.), a KL2 Fellowship (P.J.Y.) through the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: P.J.Y.; Methodology: P.J.Y., E.T., N.A.L.H., and A.Z.; Analysis: N.A.L.H., A.Z., and M.L.C.; Writing: P.J.Y, N.A.L.H., A.Z., B.Ø., E.T., M.C.L., and S.B.; Supervision: P.J.Y.; Funding Acquisition: P.J.Y.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 23, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102355.

Supplemental information

References

- Arya D., Chowdhury S., Chawla R., Das A., Ganie M.A., Kumar K.P., Nadkar M.Y., Rajput R. Clinical benefits of fixed dose combinations translated to improved patient compliance. J. Assoc. Physicians India. 2019;67:58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendixsen D.P., Østman B., Hayden E.J. Negative epistasis in experimental RNA fitness landscapes. J. Mol. Evol. 2017;85:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s00239-017-9817-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beppler C., Tekin E., Mao Z., White C., Mcdiarmid C., Vargas E., Miller J.H., Savage V.M., Yeh P.J. Uncovering emergent interactions in three-way combinations of stressors. J. R. Soc. Interf. 2016;13:20160800. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beppler C., Tekin E., White C., Mao Z., Miller J.H., Damoiseaux R., Savage V.M., Yeh P.J. When more is less: emergent suppressive interactions in three-drug combinations. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17:107. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1017-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss C. The toxicity of poisons applied jointly. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1939;26:585–615. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom D.E., Black S., Salisbury D., Rappuoli R. Antimicrobial resistance and the role of vaccines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2018;115:12868–12871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717157115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollenbach T. Antimicrobial interactions: mechanisms and implications for drug discovery and resistance evolution. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015;27:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollenbach T., Quan S., Chait R., Kishony R. Nonoptimal microbial response to antibiotics underlies suppressive drug interactions. Cell. 2009;139:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chait R., Craney A., Kishony R. Antibiotic interactions that select against resistance. Nature. 2007;446:668–671. doi: 10.1038/nature05685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevereau G., Bollenbach T. Systematic discovery of drug interaction mechanisms. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015;11:807. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chokshi A., Sifri Z., Cennimo D., Horng H. Global contributors to antibiotic resistance. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2019;11:36. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_110_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churski K., Kaminski T.S., Jakiela S., Kamysz W., Baranska-Rybak W., Weibel D.B., Garstecki P. Rapid screening of antibiotic toxicity in an automated microdroplet system. Lab Chip. 2012;12:1629–1637. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21284f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokol M., Chua H.N., Tasan M., Mutlu B., Weinstein Z.B., Suzuki Y., Nergiz M.E., Costanzo M., Baryshnikova A., Giaever G. Systematic exploration of synergistic drug pairs. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:544. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokol M., Weinstein Z.B., Yilancioglu K., Tasan M., Doak A., Cansever D., Mutlu B., Li S., Rodriguez-Esteban R., Akhmedov M. Large-scale identification and analysis of suppressive drug interactions. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos M.G., Bollenbach T. Suppressive drug interactions between antifungals. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:439–440. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean Z., Maltas J., Wood K. Antibiotic interactions shape short-term evolution of resistance in E. faecalis. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008278. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach M.A. Combination therapies for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011;14:519–523. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser T. On atropia as a physiological antidote to the poisonous effects of physostigma. Practitioner. 1870;4:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser T.R. 5. An experimental research on the antagonism between the actions of physostigma and atropia. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. 1872;7:506–511. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser T.R. Lecture on the antagonism between the actions of active substances. Br. Med. J. 1872;2:457. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.617.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French G., Ling T., Davies D., Leung D. Antagonism of ceftazidime by chloramphenicol in vitro and in vivo during treatment of gram negative meningitis. Br. Med. J. (Clinical Res. Ed.) 1985;291:636. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6496.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegreness M., Shoresh N., Damian D., Hartl D., Kishony R. Accelerated evolution of resistance in multidrug environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:13977–13981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805965105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzir I., Cokol M., Aldridge B.B., Alon U. Prediction of ultra-high-order antibiotic combinations based on pairwise interactions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:e1006774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper M.H., Dowling H.F. Treatment of pneumococcic meningitis with penicillin compared with penicillin plus aureomycin: studies including observations on an apparent antagonism between penicillin and aureomycin. AMA Arch. Intern. Med. 1951;88:489–494. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1951.03810100073006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Gefen O., Ronin I., Bar-Meir M., Balaban N.Q. Effect of tolerance on the evolution of antibiotic resistance under drug combinations. Science. 2020;367:200–204. doi: 10.1126/science.aay3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukačišin M., Bollenbach T. Emergent gene expression responses to drug combinations predict higher-order drug interactions. Cell Syst. 2019;9:423–433. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw L., Mursleen S., Irlam J.H., Spaulding A.B., Rutherford G.W., Siegfried N. Efavirenz or nevirapine in three-drug combination therapy with two nucleoside or nucleotide-reverse transcriptase inhibitors for initial treatment of HIV infection in antiretroviral-naïve individuals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016;12:CD004246. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004246.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel J.-B., Yeh P.J., Chait R., Moellering R.C., Kishony R. Drug interactions modulate the potential for evolution of resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:14918–14923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800944105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto M., Shimakawa S., Hashimoto T., Kitaoka T., Kyotani S. Marked efficacy of combined three-drug therapy (Sodium Valproate, Topiramate and Stiripentol) in a patient with Dravet syndrome. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2018;43:571–573. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østman B., Hintze A., Adami C. Impact of epistasis and pleiotropy on evolutionary adaptation. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2011;279:247–256. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto-Hanson L., Grabau Z., Rosen C., Salomon C., Kinkel L.L. Pathogen variation and urea influence selection and success of Streptomyces mixtures in biological control. Phytopathology. 2013;103:34–42. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-12-0129-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A.C., Toprak E., Baym M., Kim S., Veres A., Bershtein S., Kishony R. Delayed commitment to evolutionary fate in antibiotic resistance fitness landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povolo V.R., Ackermann M. Disseminating antibiotic resistance during treatment. Science. 2019;364:737–738. doi: 10.1126/science.aax6620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieg S., Kern W.V., Soriano A. Rifampicin in treating S aureus bacteraemia. The Lancet. 2018;392:554–555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gorostiaga A., Bajić D., Osborne M.L., Poyatos J.F., Sanchez A. High-order interactions distort the functional landscape of microbial consortia. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Yeh P.J. Suppressive drug combinations and their potential to combat antibiotic resistance. J. Antibiot. 2017;70:1033. doi: 10.1038/ja.2017.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergiopoulou T., Meletiadis J., Sein T., Papaioannidou P., Walsh T.J., Roilides E. Synergistic interaction of the triple combination of amphotericin B, ciprofloxacin, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5923–5929. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00548-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Sanderson P.E., Zheng W. Drug combination therapy increases successful drug repositioning. Drug Discov. Today. 2016;21:1189–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Vilar S., Tatonetti N.P. High-throughput methods for combinatorial drug discovery. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:205rv1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin E., Beppler C., White C., Mao Z., Savage V.M., Yeh P.J. Enhanced identification of synergistic and antagonistic emergent interactions among three or more drugs. J. R. Soc. Interf. 2016;13:20160332. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin E., Savage V.M., Yeh P.J. Measuring higher-order drug interactions: a review of recent approaches. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2017;4:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin E., White C., Kang T.M., Singh N., Cruz-Loya M., Damoiseaux R., Savage V.M., Yeh P.J. Prevalence and patterns of higher-order drug interactions in Escherichia coli. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2018;4:31. doi: 10.1038/s41540-018-0069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toprak E., Veres A., Yildiz S., Pedraza J.M., Chait R., Paulsson J., Kishony R. Building a morbidostat: an automated continuous-culture device for studying bacterial drug resistance under dynamically sustained drug inhibition. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:555. doi: 10.1038/nprot.nprot.2013.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigelny I.F. Artificial intelligence in drug combination therapy. Brief. Bioinformatics. 2019;20:1434–1448. doi: 10.1093/bib/bby004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers M., Wright G.D. Drug combinations: a strategy to extend the life of antibiotics in the 21st century. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:141–155. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood K.B., Cluzel P. Trade-offs between drug toxicity and benefit in the multi-antibiotic resistance system underlie optimal growth of E. coli. BMC Syst. Biol. 2012;6:48. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Vol. 1. Proceedings of the sixth international congress of Genetics; 1932. The Roles of Mutation, Inbreeding, Crossbreeding, and Selection in Evolution; pp. 356–366. [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Surfaces of selective value revisited. Am. Nat. 1988;131:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh P., Tschumi A.I., Kishony R. Functional classification of drugs by properties of their pairwise interactions. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:489. doi: 10.1038/ng1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and code has been made freely available via Mendeley Data (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ts2hnd72yf/1).