Summary

Background & Aims

Cholangiocyte senescence is important in the pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). We found that CDKN2A (p16), a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and mediator of senescence, was increased in cholangiocytes of patients with PSC and from a PSC mouse model (multidrug resistance 2; Mdr2-/-). Given that recent data suggest that a reduction of senescent cells is beneficial in different diseases, we hypothesised that inhibition of cholangiocyte senescence would ameliorate disease in Mdr2-/- mice.

Methods

We used 2 novel genetic murine models to reduce cholangiocyte senescence: (i) p16Ink4a apoptosis through targeted activation of caspase (INK-ATTAC)xMdr2-/-, in which the dimerizing molecule AP20187 promotes selective apoptotic removal of p16-expressing cells; and (ii) mice deficient in both p16 and Mdr2. Mdr2-/- mice were also treated with fisetin, a flavonoid molecule that selectively kills senescent cells. p16, p21, and inflammatory markers (tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-α, IL-1β, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1]) were measured by PCR, and hepatic fibrosis via a hydroxyproline assay and Sirius red staining.

Results

AP20187 treatment reduced p16 and p21 expression by ~35% and ~70% (p >0.05), respectively. Expression of inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1) decreased (by 60%, 40%, and 60%, respectively), and fibrosis was reduced by ~60% (p >0.05). Similarly, p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice exhibited reduced p21 expression (70%), decreased expression of TNF-α, IL-1β (60%), and MCP-1 (65%) and reduced fibrosis (~50%) (p >0.05) compared with Mdr2-/- mice. Fisetin treatment reduced expression of p16 and p21 (80% and 90%, respectively), TNF-α (50%), IL-1β (50%), MCP-1 (70%), and fibrosis (60%) (p >0.05).

Conclusions

Our data support a pathophysiological role of cholangiocyte senescence in the progression of PSC, and that targeted removal of senescent cholangiocytes is a plausible therapeutic approach.

Lay summary

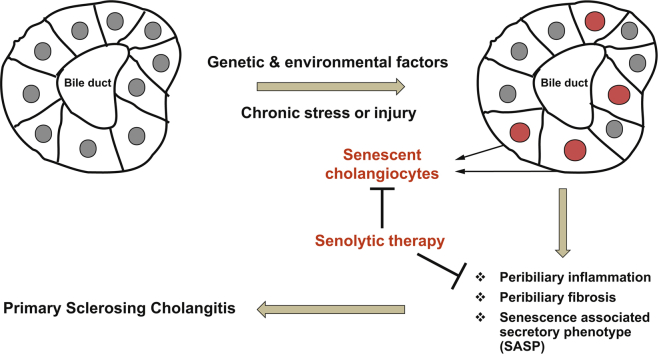

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a fibroinflammatory, incurable biliary disease. We previously reported that biliary epithelial cell senescence (cell-cycle arrest and hypersecretion of profibrotic molecules) is an important phenotype in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Herein, we demonstrate that reducing the number of senescent cholangiocytes leads to a reduction in the expression of inflammatory, fibrotic, and senescence markers associated with the disease.

Keywords: Primary sclerosing cholangitis, Cellular senescence, Apoptosis resistance, Cholestatic liver disease, Biliary epithelial cell, Senolytics, Senescence-associated secretory phenotype

Abbreviations: α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; β-Gal, β-galactosidase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AP, AP20187; Bcl-xL, B-cell lymphoma-extra large; BCL2, B cell lymphoma 2; CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; CKI, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor; Col.1A, collagen 1A; D, dasatinib; EVs, extracellular vesicles; FKBP-Casp8, FK506-binding-protein-caspase 8; IF, immunofluorescence; INK-ATTAC, p16Ink4a apoptosis through targeted activation of caspase; IR, irradiation; MCL1, myeloid cell leukemia 1; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NHC, normal human cholangiocyte; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; Q, quercetin; qPCR, quantitative PCR; RT, reverse transcription; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-gal; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; WT, wild-type

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

p16 and p21 are major mediators of cellular senescence and are highly expressed in cholangiocytes in a Mdr2-/- murine model of PSC.

-

•

The senescence-associated secretory phenotype markers are all increased in cholangiocytes of Mdr2-/- mice.

-

•

Genetic and pharmacological elimination of senescent cholangiocytes reduces peribiliary inflammation and fibrosis in Mdr2-/- mice.

-

•

Preclinical work suggests that fisetin, a naturally occurring and safe senolytic flavonoid, has the potential to be tested in patients with PSC.

Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic, progressive cholestatic liver disease of unknown aetiology characterised by peribiliary inflammation and fibrosis that ultimately progress to bile duct obliteration, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease.1,2 PSC represents a major risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma (CCA),3 and is a leading indication for liver transplant in northern Europe and the USA.1 Given the morbidity and mortality of PSC and the lack of effective pharmacotherapy, a better understanding of the molecular mediators of PSC pathogenesis and identification of new therapeutic molecular targets are needed. Studies over the past decade have underscored an important role of cellular senescence in the pathogenesis of PSC.[4], [5], [6], [7] Cholangiocytes in the bile ducts from patients with PSC and the multidrug-resistance 2 (Mdr2)-/- mouse, a well-accepted murine model of PSC, exhibit an abundance of various markers of cellular senescence.4,7,8

Cellular senescence is a cellular response to chronic injury that initially involves cell cycle arrest and the loss of cellular proliferative capacity.[9], [10], [11] Senescent cells frequently express a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), a secretome characterized by the increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, growth factors, metalloproteases, and extracellular vesicles.[11], [12], [13] Those molecules are also secreted by non-senescent cells (i.e. immune cells). Hence, it is important to use other markers [i.e. p16, p21, and β-galactosidase (β-Gal) staining] to detect senescent cells. SASP factors can alter the microenvironment, reinforce the senescent phenotype, and initiate both beneficial and injurious cellular responses.13,14 Senescent cells also highly express antiapoptotic B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) proteins [BCL2, B cell lymphoma-extra large (BCL-XL), and myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL1)] and, therefore, are resistant to apoptosis.10,11 Thus, cellular senescence has emerged as an important cellular process in health and disease displaying both beneficial (e.g. tumour suppression, tissue repair, and developmental programming) and detrimental (e.g. inflammation, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis) effects.15,16 Accumulation of senescent cells has been observed at sites of age-related diseases, including atherosclerosis, osteoarthritis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[16], [17], [18], [19] As a result, drugs that kill or modify senescent cells (referred to as senolytic and senomorphic therapy, respectively) have received much attention and are currently in clinical trials.20,21 Senolytics, compounds that selectively target senescent cells, were first discovered in 2015 when a combination of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, dasatinib (D) and the flavonoid, quercetin (Q) was shown to selectively eliminate senescent cells in vitro.22 BH3 mimetics inhibit antiapoptotic BCL2 family members and selective BH3 mimetics have also shown promise as senolytic agents.23 Indeed, it was previously showed that the proapoptotic BH3-only mimetic, navitoclax and A1331852, potent BCL-XL inhibitors, targeted senescent cholangiocytes in vivo and reversed peribiliary fibrosis in the Mdr2-/- mouse.24 However, these and other senolytic compounds are often associated with significant adverse effects (e.g. neutropoenia and thrombocytopaenia).25

Therefore, we explored the efficacy of other potential senolytic molecules as therapies in in vitro and in vivo models of PSC. As proof of concept, 2 genetic models were used to manipulate the expression of p16Ink4a in Mdr2-/- mice, a well-accepted animal model of PSC, and assessed disease progression. Next, multiple senolytic molecules were examined in vitro after experimental induction of senescence in normal human cholangiocytes (NHCs). Lastly, based on the results of the in vitro studies, Mdr2-/- mice were treated with fisetin, a novel senolytic molecule, and the inflammation and fibrosis associated with the disease were assessed.

Materials and methods

Animal models

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Upon Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval, C57BL/6J background Mdr2-/- mice were obtained as a gift from Dr. Oude Elferink (Tytgat Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). C57BL/6J background (wild-type; WT) mice were obtained from Jackson Labs. C57BL/6J-background p16Ink4a-apoptosis through targeted activation of caspase (INK-ATTAC) and p16-/-, a transgenic mouse homozygous for a null allele of the p16Ink4a gene, were obtained as a gift from Dr. James Kirkland and Dr. Darren Baker (Mayo Clinic). Ink4a refers to the family of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs). This member of this family, p16INK4a, is an inhibitor of CDK4 (hence its name, INhibitor of CDK4). Mice were housed at the Mayo Clinic animal care facility with a standard 12:12 h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to water and a standard rodent diet. A PCR-based method was used for INK-ATTAC and p16-/- transgene identification (primer sequences are available upon request).

Animal studies

For AP20187 (ARIAD Pharmaceuticals) treatments, INK-ATTACxMdr2-/-animals were injected i.p. every 7 days for 2 months with (10 mg/kg body weight) of the dimer-inducing drug and then with vehicle from 4 months onwards. Mdr2-/- and INK-ATTAC transgenic mice (WT) injected with wAP20187 had no liver phenotype (data not shown).26 INK-ATTAC mice had no liver phenotype compared with WT mice (data not shown). In addition, no phenotypic differences (i.e. body and liver weights, liver enzymes, and fibrosis) were observed between Mdr2-/- and INK-ATTACxMdr2-/- animals (Supplementary Fig. S1). For oral administration of fisetin, 4-month-old mice were dosed with (100 mg/kg body weight) fisetin (Sigma, cat no. F4043) in 60% Phosal 50 PG:30% PEG400:10% ethanol or vehicle only by gavage every 7 days for 2 months. p16-/-, Mdr2-/-, and p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice were harvested after 2 months to determine whether absence of p16Ink4a delayed the progression of the disease. No any phenotypic changes were observed between WT mice and p16-/- mice.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

Total RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol Reagent (Ambion by Life Technologies). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed starting from 500 ng of total RNA. Quantitative (q)PCR was performed in a total volume of 10 μl containing 10 ng cDNA/reaction. Target gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method and expression was normalized to 18s expression levels.

Statistical analysis

All data are reported as the mean (or fold change in mean) ± SD from a minimum of 5 independent animals. Prism software was used for the generation of all bar graphs and statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed with 1-way ANOVA, including Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for all comparisons between different animal groups. A detailed description of all methods is provided in the supplemental information online.

Results

AP20187 treatment eliminates senescent cholangiocytes in the Mdr2-/- mouse model of PSC

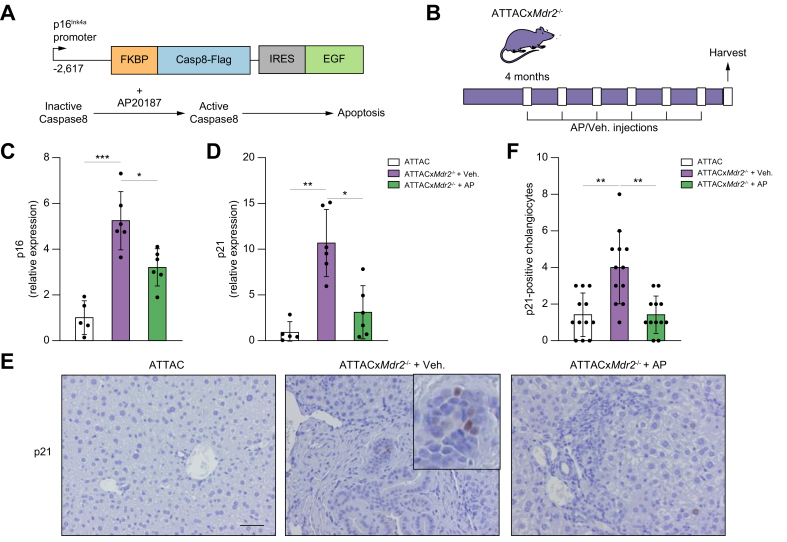

To further dissect the role of cellular senescence in the pathogenesis and progression of PSC, and to address whether induced death of senescent cholangiocytes improves the inflammation and fibrosis phenotypes associated with the disease, a murine model of PSC, the Mdr2-/-mouse,27,28 was crossbred with the INK-ATTAC mouse, a well-established transgenic model, which allowed removal of p16Ink4a-expressing senescent cells (Fig. 1A). Briefly, a 2,617-base pair (bp) fragment of the p16Ink4A gene promoter that is transcriptionally active in senescent cells drives the expression of a membrane-bound myristoylated FK506-binding-protein-caspase 8 (FKBP-Casp8) fusion protein. Upon administration of AP20187, a synthetic drug that induces membrane-bound FKBP-Casp8 dimerization, apoptosis is induced in cells expressing p16Ink4A.26 A double-homozygous INK-ATTACxMdr2-/- mouse (hereafter ATTACxMdr2-/-) was successfully bred. ATTACxMdr2-/- mice were injected with AP20187 intraperitoneally every 7 days for 2 months from 16 weeks of age (Fig. 1B). Two other groups, of age-matched ATTACxMdr2-/- vehicle-treated and WT controls, were also maintained. Upon harvesting, body and liver weights, and serum biochemistries were measured, with no differences observed between groups (data not shown). The system was validated by measuring the expression of p16 in the liver upon AP20187 treatment. The gene expression level of p16 as assessed by RT-PCR was significantly reduced (by ~40%) in the ATTACxMdr2-/- mice compared with the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 1C). The expression level of another cellular senescence mediator, p21, a CKI, was also decreased (~70%) in the liver of the ATTACxMdr2-/- group that received AP20187 (Fig. 1D). To further validate whether AP20187 treatment was selectively clearing senescent cholangiocytes, immunohistochemistry was performed to visualize p21 expression in the liver. More p21-positive senescent cholangiocytes were detected in ATTACxMdr2-/- compared with WT liver, and AP20187 treatment reduced the number of p21-positive cholangiocytes by approximately 2-fold (Fig. 1E,F). Taken together, these results provide evidence for the removal of senescent cholangiocytes in the ATTACxMdr2-/- mouse upon AP20187 treatment.

Fig. 1.

Genetic deletion of senescent cholangiocytes in the Mdr2-/- mouse model of PSC.

(A) Schematic diagram of the INK-ATTAC suicide gene. AP, a synthetic drug that induces membrane-bound FKBP-Casp8 dimerization, resulted in apoptosis in cells expressing p16Ink4A. (B) Schematic of the experimental design. Crossbred ATTACxMdr2-/- mice at 4 months of age received AP and vehicle injections every 7 days. (C,D) p16 and p21 mRNA expression in whole-liver tissue, as assessed by RT-PCR, were significantly decreased in ATTACxMdr2-/- mice following AP treatment. (E) Representative images of p21 immunohistochemistry of WT (left), ATTACxMdr2-/- vehicle-treated (middle), and ATTACxMdr2-/- AP-treated (right) mice. Magnification: 20×. Thus, AP treatment reduced the number of p21-positive cholangiocytes. (F) Quantification of p21-positive cholangiocytes. Each dot represents an image with at least 1 bile duct. Bars represent mean ± SD; n = 5–7. Scale bar: 50 μm (E). ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.001, ∗∗∗p <0.0001 (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). AP, AP20187; FKBP-Casp8, FK506-binding-protein-caspase 8; (INK-)ATTAC, p16Ink4a apoptosis through targeted activation of caspase; Mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; RT, reverse transcription; WT, wild-type.

Clearance of p16-positive senescent cholangiocytes decreases peribiliary fibrosis and inflammation in the Mdr2-/- mouse

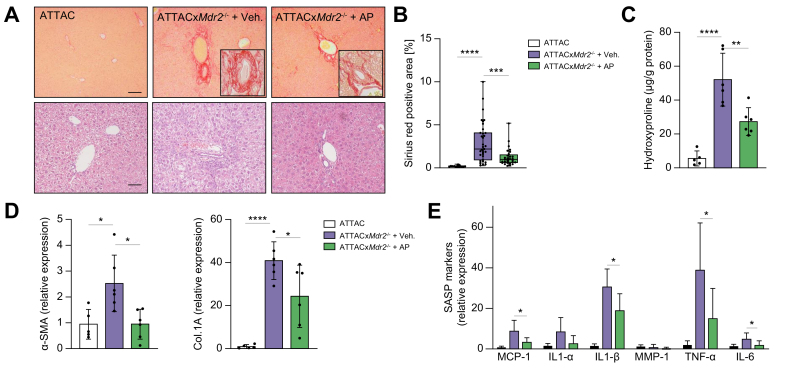

To address whether the diminished number of senescent cholangiocytes in the ATTACxMdr2-/- AP20187-treated mice suppressed the proinflammatory response and delayed disease progression, multiple inflammatory and fibrotic indices were analysed. First, based on histopathological evaluation of Picrosirius red-stained sections, hepatic fibrosis was scored blindly, and a 60% reduction in peribiliary fibrosis upon AP20187 treatment was observed (Fig. 2A,B). Moreover, quantification of collagen level in the liver by measuring the hydroxyproline concentration also confirmed the reduction in fibrosis (~50%) in the ATTACxMdr2-/- AP20187-treated mice compared with the control group (Fig. 2C). However, the hydroxyproline level in the AP20187-treated group was significantly elevated compared with the WT group. We believe that modifications in concentrations and/or experimental design in future studies could improve these results.

Fig. 2.

Genetic deletion of senescent cholangiocytes decreases inflammatory and fibrotic markers.

(A) Representative images of Picrosirius-red-stained liver sections (magnification: 10×) showing deposition of collagen (upper panel) and H&E-stained liver sections (magnification: 20×) showing generalised visualisation of liver parenchyma (lower panel) from WT mice (left), ATTACxMdr2-/- vehicle-treated mice (middle), and ATTACxMdr2-/- AP-treated mice (right). Based on histopathological evaluation of Picrosirius-red-stained liver sections, a significant reduction in fibrosis was observed in the ATTACxMdr2-/- AP-treated mice. (B) Quantification of Picrosirius-red-stained liver sections; data presented as the percentage of red stain-positive areas. Each dot represents an image with at least 1 bile duct. (C) Biochemical assessment of hepatic fibrosis confirmed marked decreased hydroxyproline concentration upon AP treatment. (D,E) mRNA expression of fibrotic markers (α-SMA and Col.1A) and SASP markers (MCP-1, IL-1α, IL-1β, MMP-1, TNF-α, and IL-6) in whole-liver tissue was significantly reduced, except those marked ‘n.s.’, in the ATTACxMdr2-/- AP-treated mice, as assessed by RT-PCR. Bars represent mean ± SD; n = 5–7. Scale bars: 100 and 50 μm (A). ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.001, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001 (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; AP, AP20187; Col.1A, collagen 1A; (INK-)ATTAC, p16Ink4a apoptosis through targeted activation of caspase; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; Mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; MMP-1, matrix metalloproteinase 1; RT, reverse transcription; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; WT, wild-type.

Further analysis of fibrotic markers showed that clearance of p16-positive senescent cholangiocytes in the ATTACxMdr2-/- mice upon AP20187 treatment markedly decreased α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; 60%) and collagen (Col)-1A (40%) gene expression, as assessed by RT-PCR, compared with the ATTACxMdr2-/- vehicle-treated group (Fig. 2D). SASP is a spectrum of proinflammatory molecules that detrimentally affect tissue homeostasis in various chronic diseases.13 SASP markers (i.e. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1) were all significantly reduced (60%, 40%, 60%, and 60%, respectively) upon AP20187 treatment (Fig. 2E).

In summary, these results suggest that there is an association between cholangiocyte senescence and disease progression in the Mdr2-/- mouse, and that targeting of senescent cholangiocytes reduces both fibrosis and inflammation associated with the disease.

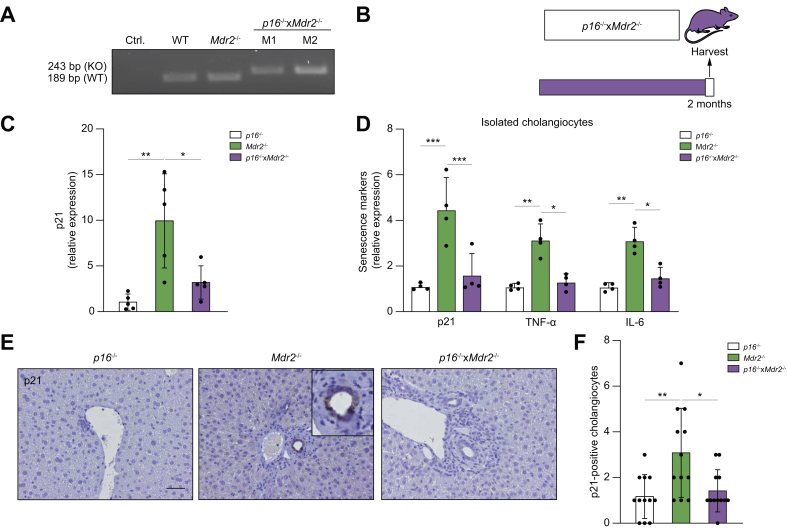

Knockdown of p16 decreases senescence markers in the liver of the Mdr2-/- mouse

Given that targeted removal of p16Ink4a-expressing senescent cells decreased peribiliary fibrosis in the Mdr2-/- mouse, we sought to determine whether genetic reduction of p16Ink4a in the liver would also delay or prevent development of the disease in Mdr2-/- mice. To do so, the p16-/- mouse, a transgenic mouse homozygous for a null allele of the p16Ink4a gene, was crossbred with the Mdr2-/- mouse to generate a transgenic cholestatic disease murine model homozygous for the p16Ink4a gene (Fig. 3A). Three groups of age-matched mice were maintained: (i) p16-/- control; (ii) Mdr2-/-; and (iii) p16-/-xMdr2-/-. All mice were sacrificed at 2 months of age (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Genetic reduction of p16 reduces senescence markers in the Mdr2-/- mouse.

(A) PCR genotyping showing the p16-/- DNA construct. (KO) band represents the neomycin-resistance cassette on exon-1α of the Ink4a/Arf/Ink4b locus. (B) Schematic of the experimental design. P16-/-, Mdr2-/-, and crossbred p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice were harvested at 2 months of age. (C) Hepatic p21 mRNA expression, as assessed by RT-PCR, was reduced in p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice. (D) mRNA expression of senescence markers in isolated cholangiocytes, as assessed by RT-PCR, was reduced in p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice. (E) Representative images of p21 immunohistochemistry of p16-/- (left), Mdr2-/- (middle), and p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice (right) (magnification: 20×). A significant reduction in the number of p21-positive cholangiocytes was observed in p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice compared with the control group. (F) Quantification of p21-positive cholangiocytes. Each dot represents an image with at least 1 bile duct. Bars represent mean ± SD; n = 5–7. Scale bar: 50 μm (D). ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.01, (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; RT, reverse transcription; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; WT, wild-type.

There were no differences in gross appearance, body and liver weights at the time of sacrifice between groups (data not shown). Markers of cellular senescence, including expression level of p21, were examined. The gene expression level of p21 was significantly reduced (up to ~70%) in the liver of the p16-/-xMdr2-/- group (Fig. 3C). To further validate whether markers of cellular senescence were reduced in cholangiocytes, cholangiocytes and hepatocytes were isolated from the p16-/-, Mdr2-/-, and p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice and various markers of cellular senescence were measured. A >50% reduction in senescence markers (i.e. p21, TNF-α, and IL-6) was observed in cholangiocytes isolated from p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice (Fig. 3D). As expected, hepatocytes isolated from Mdr2-/- and p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice did not exhibit a significant increase in the various senescence markers (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Moreover, the number of p21-positive cholangiocytes, quantified using immunohistochemistry, was also reduced by 2-fold in the p16-/-xMdr2-/-group compared with Mdr2-/- mice (Fig. 3E,F). In addition, the p21 expression level was quantified in biliary epithelial cell structures that extended into the liver parenchyma, a cellular phenomenon described as the ductular reaction.29 No changes were observed between the p16-/-, Mdr2-/-, and p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Altogether, these data indicate that markers of cellular senescence were increased in cholangiocytes of Mdr2-/- mice, and that the absence of p16 reduced markers of cholangiocyte senescence in the liver.

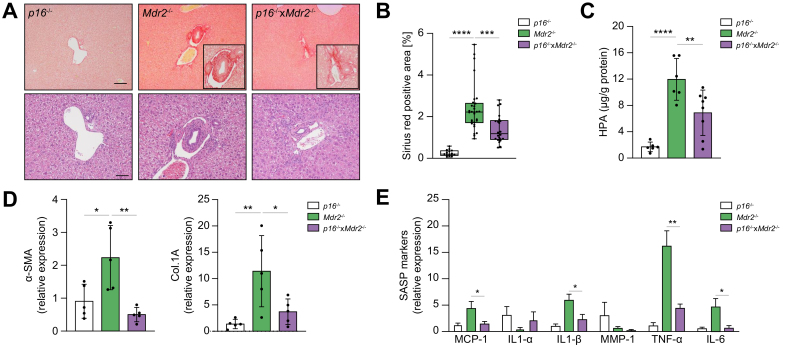

Knockdown of p16 delays peribiliary inflammation and fibrosis in the liver of the Mdr2-/- mouse

We investigated whether the p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice at 2 months of age exhibited less biliary disease than that seen in Mdr2-/- mice. Initially, serum biochemical markers relevant to hepatobiliary disease were analysed. Serum levels of the liver enzyme, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), were significantly reduced by 40% in p16-/-xMdr2-/- compared with Mdr2-/- mice (data not shown); other serum biochemistries showed no change between the groups. Picrosirius-red staining was then performed on liver sections, which were then scored blindly for severity of hepatic fibrosis. The p16-/-xMdr2-/-mice exhibited a ~50% reduction in peribiliary fibrosis compared with Mdr2-/- mice (Fig. 4A,B). Additionally, a corresponding decrease (40%) in hydroxyproline concentration was also observed in p16-/-xMdr2-/-mice (Fig. 4C). Further analysis of profibrotic markers (α-SMA and Col.1A), and SASP markers (i.e. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1), using RT-PCR of whole-liver tissue, showed substantial decreases (80%, 65%, 70%, 60%, 80%, and 65%, respectively) in p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice compared with Mdr2-/- mice (Fig. 4D,E). In summary, these findings show that genetic reduction of p16 in the liver, a major regulator of cellular senescence, delayed inflammation and fibrosis associated with the Mdr2-/- mouse model of PSC.

Fig. 4.

Genetic reduction of p16 decreases hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.

(A) Representative images of Picrosirius-red-stained liver sections (magnification: 10×) showing deposition of collagen (upper panel) and H&E-stained liver sections (magnification: 20×) showing generalized visualization of liver parenchyma (lower panel) of p16-/- (left), Mdr2-/- (middle), and p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice (right) (magnification: 20×). p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice exhibited a marked reduction in hepatic fibrosis. (B) Quantification of Picrosirius-red-stained liver sections; data presented as % red stain positive area. Each dot represents an image with at least 1 bile duct. (C) Biochemical assessment of hepatic fibrosis confirmed a markedly decreased hydroxyproline concentration in p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice. (D,E) Analysis of multiple fibrotic (a-SMA and Col.1A) and SASP genes (MCP1, IL1a, IL1b, MMP1, TNFa, and IL6) by RT-PCR showing significant reduction, except those marked ‘n.s.’, in whole-liver tissue from p16-/-xMdr2-/- mice. Bars represent mean ± SD; n = 5–7. Scale bars: 100 and 50 μm (A). ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.001, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001 (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). a-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; Col.1A, collagen 1A; MCP1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; Mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; MMP-1, matrix metalloproteinase 1; RT, reverse transcription; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; WT, wild-type.

Fisetin, a novel senolytic molecule, selectively targets senescent cholangiocytes in vitro

To selectively clear senescent cholangiocytes in vivo using a pharmacological approach, multiple senolytic compounds were tested in vitro using NHCs. D, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and the flavonoid Q were among the first compounds discovered to selectively eliminate senescent cells in vitro and in vivo.22 In addition, the BCL-2/ BCL-W/ BCL-XL inhibitor, navitoclax (ABT263), and the BCL-XL inhibitor, A1331852 have been reported to be senolytics, and can selectively kill senescent cholangiocytes.23,24 Fisetin, another flavonoid, was recently found to selectively eliminate senescent cells.30 To determine whether D, Q, and fistein can selectively kill senescent cholangiocytes in vitro, a cellular survival assessment was performed using the Crystal violet assay. NHCs were exposed to 10 GY radiation to induce senescence, a model previously developed by the authors.24 Cells were then treated with these compounds in a dose-dependent manner for 24 h. Similar to A1331852, fisetin at 50 μM reduced the number of senescent non-proliferating cholangiocytes (Fig. 5A), but not proliferating cholangiocytes. A combination of D and Q reduced the number of both senescent and proliferating cholangiocytes (Fig. 5A). To test whether these compounds induced cell death in senescent cholangiocytes, apoptosis was assessed by measuring Casp3/7 activity. Similar to A1331852, fistein at 50 μM induced apoptosis in senescent cholangiocytes (Fig. 5B,C). A higher concentration of fistein (i.e. >100 μM) induced cell death in both senescent and proliferating cholangiocytes. D and Q induced apoptosis in both senescent and proliferating cholangiocytes (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Fisetin targets senescent cholangiocytes in vitro.

(A) Senolytic compounds at various concentrations were applied to proliferating and senescent cholangiocytes (induced experimentally by irradiation). Fisetin and A1331 significantly reduced the number of senescent cholangiocytes as measured by Crystal violet. Bars represent mean ± SEM; n = 4. (B,C) Fisetin and A1331 induced apoptosis in senescent cholangiocytes. (D) Fisetin did not induce apoptosis in non-proliferating or non-senescent cholangiocytes. Proliferating and senescent cholangiocytes were treated with fisetin and A1331, respectively for 12 h and Caspase-3/7 activity was measured using a luminescent substrate. (F) Fisetin did not induce apoptosis in isolated hepatocytes from WT or Mdr2-/- mice. Data represent mean ± SD; n = 4 at each concentration. ∗p <0.01 (Student’s t test). Mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; NHC, normal human cholangiocyte; WT, wild-type.

To determine the effect of senolytics on non-proliferating and non-senescent cholangiocytes, cholangiocytes were incubated with a low concentration of foetal bovine serum, which forced the cholangiocytes to enter a state of no proliferation (quiescence). Upon incubation with A1331582 and fisetin, no induction of apoptosis was observed at 1 μm and 50 μm, respectively as measured by Casp3/7 activity (Fig. 5D).

We then investigated whether senolytics could target other cell types in the liver. Hepatocytes were isolated from WT and Mdr2-/- liver and treated with fistein at various concentrations. Fisetin did not induce apoptosis in hepatocytes at similar concentrations used to induce apoptosis in senescent cholangiocytes (Fig. 5E). These results demonstrate that fisetin acts as a senolytic in vitro, can selectively clear senescent cholangiocytes, and is a potential candidate for testing in vivo.

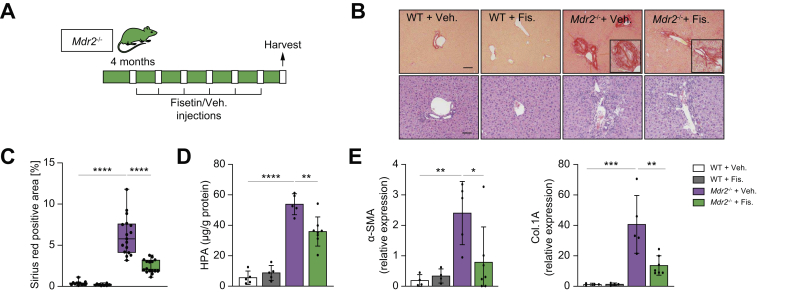

Fisetin-treatment decreases fibrotic, inflammatory and senescence markers in the Mdr2-/- mouse

To assess the potential clinical relevance of our in vitro findings, we examined whether fisetin could ameliorate peribiliary fibrosis in the Mdr2-/- mouse. Fisetin was administrated by gavage to WT control and Mdr2-/- mice from 4 months of age by gavage every 7 days for 2 months (Fig. 6A). There were no differences in gross appearance, body and liver weights, and serum biochemistry between the groups (data not shown). Fibrosis was assessed morphometrically in Picrosirius red-stained sections and a significant reduction (up to ~60%) in the percentage of fibrotic area in the fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- mice compared with the vehicle-treated group was revealed (Fig. 6B,C). Biochemical assessment of hepatic fibrosis confirmed a decreased hydroxyproline concentration (30%) in the liver of the fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- mice compared with control mice (Fig. 6D). However, the hydroxyproline level in the fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- mice was significantly elevated compared with the WT group, and it is likely that alternative dosage/treatment period might provide a better outcome.

Fig. 6.

Fisetin-treatment reduces inflammation and fibrosis in the Mdr2-/- mouse.

(A) Schematic of the experimental design. WT and Mdr2-/- mice were gavaged with fisetin and vehicle every 7 days for 2 months. (B) Representative images of Picrosirius-red-stained liver sections (10×) showing deposition of collagen (upper panel) and haematoxylin and eosin-stained liver sections (20×) showing generalized visualization of liver parenchyma (lower panel) of WT vehicle and fisetin-treated mice, and vehicle and fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- mice (20×). Based on histopathological evaluation of picrosirius-stained liver sections, a significant reduction was observed in fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- mice. (C) Quantification of Picrosirius-red-stained liver sections; data presented as the percentage of red stain-positive areas. Each dot represents an image with at least 1 bile duct. (D) Biochemical assessment of hepatic fibrosis confirmed the markedly decreased hydroxyproline concentration upon fisetin treatment. (E) Fibrotic marker assessment. The mRNA expression of α-SMA and Col.1A was reduced following fisetin treatment. Bars represent mean ± SD; n = 5–7. Scale bars: 100 and 50 μm (A). ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.001, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001 (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; Col.1A, collagen 1A; HPA, hydroxyproline; Mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; WT, wild-type.

The fibrotic markers α-SMA and Col.1A were found to be reduced (by 60%) upon fisetin treatment (Fig. 6E). Next, we determined whether the decreased peribiliary inflammation and fibrosis coincided with a reduction in the number of senescent cholangiocytes in liver. Fisetin treatment markedly reduced the number of p21-positive cholangiocytes (Fig. 7A,B). In addition, livers of fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- showed a significant decrease in hepatic expression of p16 and p21 (80% and 90%, respectively) (Fig. 7C). SASP markers TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1 mRNA levels were uniformly reduced (50%, 50%, 50%, and 60%, respectively) in fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- mice compared with vehicle-treated Mdr2-/- mice (Fig. 7D). In addition, using laser-capture microscopy, cholangiocytes and hepatocytes were sampled from Mdr2-/- mice treated with fisetin and vehicle, and various markers of cellular senescence were measured. Quantification of senescence markers (p21, TNF-α, and IL-6) showed a >50% reduction in cholangiocytes sampled from Mdr2-/- mice treated with fistein, compared with cholangiocytes sampled from Mdr2-/- mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 7E). As expected, hepatocytes isolated from Mdr2-/- mice treated with fisetin or vehicle did not exhibit any significant increase in the various senescence markers examined (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Finally, p21 expression level was quantified in the cholangiocytes of the ductular reaction, and no changes between the fisetin- and vehicle-treated Mdr2-/- mice were observed (Supplementary Fig. S3B). Collectively, these findings indicate that elimination of senescent cholangiocytes by fisetin improved the PSC-like phenotype in Mdr2-/- mice.

Fig. 7.

Fisetin treatment decreases senescence markers in the liver of the Mdr2-/- mouse.

(A) Representative images of p21 immunohistochemistry of WT vehicle and fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- vehicle and fisetin-treated mice (magnification: 20×). (B) Quantification of p21-positive cholangiocytes. Each dot represents an image with at least 1 bile duct. (C) mRNA expression of the cellular senescence mediators, p16 and p21, was decreased significantly following fisetin treatment. (D) Gene expression analysis of various SASP genes by RT-PCR showing a significant decrease, except those marked by ‘n.s.’, in whole-liver tissue of fisetin-treated Mdr2-/-mice. (E) mRNA expression of senescence markers in sampled cholangiocytes, as assessed by RT-PCR, was reduced in Mdr2-/- mice treated with fisetin. Bars represent mean ± SD; n = 5–7. Scale bar: 50 μm (A). ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.001, ∗∗∗p <0.0001 (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; Mdr2, multidrug-resistance 2; MMP-1, matrix metalloproteinase 1; RT, reverse transcription; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; WT, wild-type.

Discussion

The major findings reported here relate to the pathophysiological role of cholangiocyte senescence in the progression of an animal model of PSC and the possibility that targeted removal of senescent cholangiocytes (senolytic therapy) might be a useful therapeutic approach in this disease. Key findings showed that: (i) genetic removal of p16-positive senescent cholangiocytes by targeted apoptosis decreased peribiliary inflammation and fibrosis; (ii) genetic reduction of p16 delayed disease progression in Mdr2-/- mice; (iii) fisetin, a flavonoid senolytic, selectively targeted senescent cholangiocytes in vitro; and (iv) fisetin-treated Mdr2-/- mice showed a marked reduction in fibrotic, inflammatory, and senescence markers. These findings have clear implications for a fuller understanding the pathophysiology of biliary injury and the development of potential pharmacotherapies for PSC.

PSC, a complex disease with unknown aetiology, is characterised by peribiliary inflammation and fibrosis. Despite extensive studies, there is currently no effective, regulatory-approved pharmacotherapy. An increase in the frequency of cholangiocytes entering the senescent state has been observed with PSC, and ongoing research continues to show the importance of cellular senescence in driving chronic and age-related pathologies. Senescent cells accumulate in many vertebrate tissues (i.e. cartilage, heart, lung, liver, etc.) and contribute to an altered microenvironment through their modified secretome or SASP.14 Eliminating senescent cells has been shown to reduce tissue dysfunction in age-related pathologies, and prolong life-span.26 Thus, the aim of the current study was to identify a safe senolytic molecule that selectively targets senescent cholangiocytes, and can improve the PSC-like phenotype in the Mdr2-/- mouse.

Powerful research tools have emerged to investigate how senescent cells contribute to disease, including the INK-ATTAC (p16Ink4a apoptosis through targeted activation of caspase) mouse model that allows removal of senescent cells by drug-induced apoptosis.26 To our knowledge, this is the first time this model has been applied to eliminate senescent cells in a murine model of a cholestatic cholangiopathy; that is, the Mdr2-/- mouse model of PSC. ATTACxMdr2-/- mice were used to determine whether genetic reduction of senescent cholangiocytes would impede disease progression. AP20187 treatment caused a significant decrease in p16 and p21 gene expression in whole-liver tissue and reduced the number of p21-positive cholangiocytes. Hepatobiliary markers of inflammation and fibrosis all decreased upon reduction of cholangiocyte senescence, providing further evidence of the detrimental role of cholangiocyte senescence in the progress of the PSC-like phenotype in the Mdr2-/- mouse. To further highlight the importance of cholangiocyte senescence in the pathogenesis of PSC in the Mdr2-/- mouse, a unique, second genetic model was developed, the p16-/- mouse, a transgenic mouse homozygous for a null allele of the p16Ink4a gene, crossed with the Mdr2-/- mouse. The p16-/-xMdr2-/- cross-bred mouse was used to determine whether absence of p16-positive cholangiocytes could prevent disease progression. As predicted, the absence of p16INK4a in the liver decreased inflammation and fibrosis at 2 months. In accordance with these results, previous studies demonstrated that removal of senescent cells reversed fibrosis and inflammation in atherosclerosis, pulmonary fibrosis, steatosis, and sclerosing cholangitis.[17], [18], [19],31 Numerous studies have now discovered compounds that mimic the effects of these transgenic murine models. The term ‘Senolytics’ has come to be used to refer to compounds that selectively kill senescent cells.22 Senolytics target the anti-apoptosis pathway that is usually upregulated in senescent cells.32 It was recently shown that the BCL2 inhibitor, Navitoclax, and the BCL-XL-selective inhibitor A-1331852 targeted cholangiocyte senescence, and reduced inflammation and fibrosis in the Mdr2-/- mouse model of PSC. In the current study, fisetin, a flavonoid senolytic, caused a striking reduction in the number of senescent cholangiocytes in vitro. A combination of D and Q, 2 other senolytics, reduced the number of both proliferating and senescent cholangiocytes. This was not surprising given that other studies have shown that different cell types induced to senescence react in different ways to senolytic molecules.22,23 Based on these in vitro data, Mdr2-/- mice were treated with fisetin, resulting in a substantial decrease in inflammation and fibrosis, the number of p21-positive cholangiocytes, and numerous SASP markers, providing further evidence of the importance of cholangiocyte senescence in driving the PSC-like phenotype in the Mdr2-/- mouse and implying the usefulness of fisetin in PSC. There was no significant improvement in serum biochemistries upon fisetin treatment. This was not unexpected, given that improvements in inflammation and fibrosis are not always reflected in those laboratory values. However, other cells in the liver express p16. A recent report showed that, in ageing rodent liver, liver sinusoid endothelial cells and macrophages have increased expression of p16, and their elimination induced liver and perivascular tissue fibrosis.33 In the Mdr2-/- mice, p21 expression was only observed in cholangiocytes.

In conclusion, our data continue to support an important pathophysiological role of cholangiocyte senescence in the progression of an animal model of PSC and suggest the targeted removal of senescent cholangiocytes (senolytic therapy) as an attractive therapeutic approach. Although targeting senescent cholangiocytes via the apoptotic pathway has previously been shown to be beneficial, we believe that those inhibitors could not be used to treat patients with PSC because of their toxicity. The current work suggests that flavonols, naturally occurring compounds and historically safe, have the potential to be translated to the clinic. In the future, investigations should determine the signalling pathways that are activated/deactivated by senescent cholangiocytes, and how these pathways affect other hepatic-resident (i.e. hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and hepatic stellate cells) and recruited (i.e. macrophages) fibrogenic and immune cells. Identification of these signalling pathways can help to expand understanding of how cholangiocyte senescence contributes to PSC pathogenesis and to identify novel therapeutic approaches.

Financial support

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK57993 (to N.F.L), the Mayo Foundation, and the Clinical and Optical Microscopy Cores of the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (P30DK084567).

Author contributions

Study design: MA, SPO, NFL. Data acquisition: MA. Rodent maintenance and harvest: JEW, NEP. Data analysis: MA, SPO. Manuscript drafting and revision: MA, NFL

Data availability statement

Where possible, experimental data can be shared by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank James Kirkland, Tamar Tchkonia, Brian Davies, and members of the LaRusso laboratory for invaluable inputs on experimental design, and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100250.

Contributor Information

Mohammed Alsuraih, Email: alsuraih.mohammed@mayo.edu.

Steven P. O’Hara, Email: ohara.steven@mayo.edu.

Julie E. Woodrum, Email: broadcamping@kmtel.com.

Nicholas E. Pirius, Email: Pirius.Nicholas@mayo.edu.

Nicholas F. LaRusso, Email: larusso.nicholas@mayo.edu.

Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lazaridis K.N., LaRusso N.F. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1161–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1506330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlsen T.H., Folseraas T., Thorburn D., Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1298–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschfield G.M., Karlsen T.H., Lindor K.D., Adams D.H. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2013;382:1587–1599. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabibian J.H., O'Hara S.P., Splinter P.L., Trussoni C.E., LaRusso N.F. Cholangiocyte senescence by way of N-ras activation is a characteristic of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2014;59:2263–2275. doi: 10.1002/hep.26993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabibian J.H., Trussoni C.E., O'Hara S.P., Splinter P.L., Heimbach J.K., LaRusso N.F. Characterization of cultured cholangiocytes isolated from livers of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lab Invest. 2014;94:1126–1133. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan Y., Meng F., Wu N., Zhou T., Venter J., Francis H. Substance P increases liver fibrosis by differential changes in senescence of cholangiocytes and hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2017;66:528–541. doi: 10.1002/hep.29138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira-Gonzalez S., Lu W.Y., Raven A., Dwyer B., Man T.Y., O'Duibhir E. Paracrine cellular senescence exacerbates biliary injury and impairs regeneration. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1020. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabibian J.H., O'Hara S.P., Trussoni C.E., Tietz P.S., Splinter P.L., Mounajjed T. Absence of the intestinal microbiota exacerbates hepatobiliary disease in a murine model of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2016;63:185–196. doi: 10.1002/hep.27927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campisi J., d'Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Deursen J.M. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature. 2014;509:439–446. doi: 10.1038/nature13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez-Segura A., Nehme J., Demaria M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:436–453. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tchkonia T., Zhu Y., van Deursen J., Campisi J., Kirkland J.L. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:966–972. doi: 10.1172/JCI64098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coppe J.P., Desprez P.Y., Krtolica A., Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:99–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Suraih M.S., Trussoni C.E., Splinter P.L., LaRusso N.F., O'Hara S.P. Senescent cholangiocytes release extracellular vesicles that alter target cell phenotype via the epidermal growth factor receptor. Liver Int. 2020;40:2455–2468. doi: 10.1111/liv.14569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Childs B.G., Durik M., Baker D.J., van Deursen J.M. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med. 2015;21:1424–1435. doi: 10.1038/nm.4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munoz-Espin D., Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:482–496. doi: 10.1038/nrm3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Childs B.G., Baker D.J., Wijshake T., Conover C.A., Campisi J., van Deursen J.M. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science. 2016;354(6311):472–477. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogrodnik M., Miwa S., Tchkonia T., Tiniakos D., Wilson C.L., Lahat A. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15691. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schafer M.J., White T.A., Iijima K., Haak A.J., Ligresti G., Atkinson E.J. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14532. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirkland J.L., Tchkonia T. Cellular senescence: a translational perspective. EBioMedicine. 2017;21:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano M., Barzilai N. Targeting senescence. Nat Med. 2018;24:1092–1094. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Y., Tchkonia T., Pirtskhalava T., Gower A.C., Ding H., Giorgadze N. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell. 2015;14:644–658. doi: 10.1111/acel.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y., Tchkonia T., Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H., Dai H.M., Ling Y.Y., Stout M.B. Identification of a novel senolytic agent, navitoclax, targeting the Bcl-2 family of anti-apoptotic factors. Aging Cell. 2016;15:428–435. doi: 10.1111/acel.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moncsek A., Al-Suraih M.S., Trussoni C.E., O'Hara S.P., Splinter P.L., Zuber C. Targeting senescent cholangiocytes and activated fibroblasts with B-cell lymphoma-extra large inhibitors ameliorates fibrosis in multidrug resistance 2 gene knockout (Mdr2(-/-)) mice. Hepatology. 2018;67:247–259. doi: 10.1002/hep.29464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashkenazi A., Fairbrother W.J., Leverson J.D., Souers A.J. From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced selective BCL-2 family inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker D.J., Wijshake T., Tchkonia T., LeBrasseur N.K., Childs B.G., van de Sluis B. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smit J.J., Schinkel A.H., Oude Elferink R.P., Groen A.K., Wagenaar E., van Deemter L. Homozygous disruption of the murine mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene leads to a complete absence of phospholipid from bile and to liver disease. Cell. 1993;75:451–462. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fickert P., Fuchsbichler A., Wagner M., Zollner G., Kaser A., Tilg H. Regurgitation of bile acids from leaky bile ducts causes sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(1):261–274. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azad A.I., Krishnan A., Troop L., Li Y., Katsumi T., Pavelko K. Targeted apoptosis of ductular reactive cells reduces hepatic fibrosis in a mouse model of cholestasis. Hepatology. 2020;72:1013–1028. doi: 10.1002/hep.31211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu Y., Doornebal E.J., Pirtskhalava T., Giorgadze N., Wentworth M., Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H. New agents that target senescent cells: the flavone, fisetin, and the BCL-XL inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463. Aging (Albany NY) 2017;9:955–963. doi: 10.18632/aging.101202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyritsi K., Francis H., Zhou T., Ceci L., Wu N., Yhang Z. Downregulation of p16 decreases biliary damage and liver fibrosis in the Mdr2-/- mouse model of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gene Expr. 2020;20:89–103. doi: 10.3727/105221620X15889714507961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leverson J.D., Phillips D.C., Mitten M.J., Boghaert E.R., Diaz D., Tahir S.K. Exploiting selective BCL-2 family inhibitors to dissect cell survival dependencies and define improved strategies for cancer therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:279ra40. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grosse L., Wagner N., Emelyanov A., Molina C., Lacas-Gervais S., Wagner K.D. Defined p16(high) senescent cell types are indispensable for mouse healthspan. Cell Metab. 2020;32:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Where possible, experimental data can be shared by contacting the corresponding author.