Abstract

RRM2B plays a crucial role in DNA replication, repair and oxidative stress. While germline RRM2B mutations have been implicated in mitochondrial disorders, its relevance to cancer has not been established. Here, using TCGA studies, we investigated RRM2B alterations in cancer. We found that RRM2B is highly amplified in multiple tumor types, particularly in MYC-amplified tumors, and is associated with increased RRM2B mRNA expression. We also observed that the chromosomal region 8q22.3–8q24, is amplified in multiple tumors, and includes RRM2B, MYC along with several other cancer-associated genes. An analysis of genes within this 8q-amplicon showed that cancers that have both RRM2B-amplified along with MYC have a distinct pattern of amplification compared to cancers that are unaltered or those that have amplifications in RRM2B or MYC only. Investigation of curated biological interactions revealed that gene products of the amplified 8q22.3–8q24 region have important roles in DNA repair, DNA damage response, oxygen sensing, and apoptosis pathways and interact functionally. Notably, RRM2B-amplified cancers are characterized by mutation signatures of defective DNA repair and oxidative stress, and at least RRM2B-amplified breast cancers are associated with poor clinical outcome. These data suggest alterations in RR2MB and possibly the interacting 8q-proteins could have a profound effect on regulatory pathways such as DNA repair and cellular survival, highlighting therapeutic opportunities in these cancers.

Keywords: chromosome 8, 8q-amplicon, RRM2B, cancer, MYC

Introduction

RRM2B plays an important role in regulating replication stress, DNA damage, and genomic stability (Aye et al., 2015; Foskolou et al., 2017). RRM2B encodes a small subunit of p53-inducible ribonucleotide reductase (RNR). The RNR is a heterotetrametric enzyme responsible for the de novo conversion of ribonucleotide diphosphates into the corresponding deoxyribonucleotide diphosphates for DNA synthesis, thus playing an important role in maintaining deoxyribonucleotide pools (Okumura et al., 2005). The large subunit of the RNR complex consists of a dimer of the RRM1 protein, while the small subunit dimer is either RRM2 or RRM2B (varies depending on cellular conditions). P53-dependent induction of RRM2B expression by hypoxia leads to the exchange of the small RNR subunit from RRM2 to RRM2B, forming a new RNR complex that drives basal DNA replication, reduces replication stress, and maintains genomic stability (Wang et al., 2011; Foskolou and Hammond, 2017). These known functions of RRM2B suggest that RRM2B alterations may play a role in tumorigenesis (Aye et al., 2015; Foskolou et al., 2017).

RRM2B is located on chromosome 8q [8q23.1 (Tanaka et al., 2000); in 2018, annotation changed to 8q22.3]1. Germline missense and loss of function mutations in RRM2B have been associated with mitochondrial depletion syndrome (MDS), with distinct but variable clinical phenotype (Gorman and Taylor, 1993; Bornstein et al., 2008). At present, there are no known RRM2B germline alterations associated with cancer risk. However, somatic changes in RRM2B, including most typically amplifications, have been observed in breast, liver, lung and skin cancers (Chae et al., 2016). In a survey of the COSMIC database, RRM2B emerged as the most highly amplified DNA repair gene (Chae et al., 2016). Additionally, TCGA studies of ovarian, breast, liver, and prostate cancer, have found that cases with RRM2B copy number variations (CNV) (amplifications and deletions) have decreased overall survival (OS) (Chae et al., 2016). Similarly, increased metastasis and poor prognosis were correlated with RRM2B overexpression in head and neck cancer (Yanamoto et al., 2003), esophageal cancer (Okumura et al., 2006) and lung sarcomatoid carcinoma (Chen et al., 2017). Another study noted that elevated expression of RRM2B is associated with better survival in advanced colorectal cancer (Liu et al., 2011).

RRM2B amplification may be driven by selection of RRM2B function, or RRM2B may be amplified as a passenger, concurrent with selection for a nearby gene with a driver activity in cancer. In breast cancer, multiple genes localized in the 8q12.1–8q24.23 interval were found to be amplified, including RRM2B (Parris et al., 2014). Most RRM2B amplifications are accompanied by MYC amplifications, and these two genes are located in close proximity (Christoph et al., 1999). However, RRM2B amplifications also occur independent of MYC amplifications, albeit at a lower frequency (Kalkat et al., 2017). While multiple studies have observed the amplification of the 8q region, currently the frequency and specificity of these amplifications is not known, and more specifically, the consequence of RRM2B amplification with MYC or as independent from MYC amplification is not clearly understood (Bruch et al., 1998; Sato et al., 1999; Saha et al., 2001; Byrne et al., 2005; Ehlers et al., 2005; Ho et al., 2006; Schleicher et al., 2007; Bilal et al., 2012; Parris et al., 2014; Yong et al., 2014; Kwon et al., 2017).

Here, using data from TCGA, we found that RRM2B-amplified tumors not only exhibit increased RRM2B expression in multiple cancers (such as breast, ovarian, head, and neck cancer), but also exhibit distinct mutation signatures. Analysis of the most common breast cancer subtype indicated that RRM2B amplifications may independently impact clinical outcomes in these cancers. Further, tumors bearing RRM2B amplifications showed that several genes in the 8q22–8q24 region (along with MYC) are highly amplified. Additionally, analysis of 8q-proteins suggests functional interaction within the same cell regulatory mechanisms of DNA damage response and repair, hypoxia and apoptosis. Based on these results, we hypothesize that while MYC may be the cancer driver, co-amplification of RRM2B and other 8q-genes may be relevant for cancer cell survival. These finding suggest opportunities for novel therapeutic targeting strategies (such as those targeting DNA damage response and repair) for tumors carrying RRM2B alterations.

Materials and Methods

Analysis of Alteration Frequencies Using TCGA Studies

TCGA studies were accessed using the cBioPortal website2 (Cerami et al., 2012). Data was downloaded (on 6/21/2018) from 30 TCGA studies for tumors that have been profiled for mutations as well as copy number variants. For cancer types with the highest frequency of RRM2B amplifications, cases were segregated based on co-occurrence of TP53 mutations or MYC amplifications. The TP53 alterations were all mutations (missense, and truncating). The truncating mutations in TCGA are frameshift deletions, frameshift insertions, nonsense, splice site. All mutations were analyzed for co-occurrence, including those that were homozygous or heterozygous.

RNA Expression

RNA seq. V2 RSEM data was downloaded from OV (ovarian cancer study), BRCA (breast cancer study) and HNSC (head and neck cancer study) studies on 11/7/2018, and 3/19/2020. The RNA seq. data were only analyzed for tumors that were also profiled for copy number variants. Cases were segregated based on copy number variants type: deep deletion, shallow deletion, diploid, gain and amplification. For RRM2B there was only a single case of deep deletion out of all (n = 2,181 cases from all studies), observed in BRCA, and was removed. For CCNE2, EI3FE, MTDH, MYC, RAD21, TP53INP1, and YWHAZ—there were no cases of deep deletion for any of the genes in the HNSC study, but there was one case each in EI3FE, RAD21 and YWHAZ with deep deletions in the BRCA study, and also one case each in EI3FE and MTDH as well as two cases in RAD21 for the OV study. V2 RSEM from cases with different copy number variants categories and statistical significance was tested in Graphpad Prism 8.0 using Mann-Whitney Non-Parametric T-test (Gao and Song, 2005; Li and Tibshirani, 2013). Additionally, plots of log2 mRNA expression values based on relative linear copy number values were used to test for correlation between increasing copy number change and mRNA expression, then Pearson coefficient (Karl and Francis, 1997) and log rank (Mantel, 1966) p-values for each cancer type were calculated. Graphpad Prism 8.0 was used for all statistical analysis. For CCNE2, EI3FE, MTDH, MYC, RAD21, TP53INP1 and YWHAZ: the data were analyzed as above but are presented as Supplementary Tables with expression data and statistics.

Tumor Mutation Signatures

Tumor whole-exome sequence data in the TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas studies (for OV, BRCA, HNSC, and LUAD), that includes spectra of individual tumors, was downloaded from the Synapse platform3 on 11/5/2018. Next, IDs of subjects with different cancer types were downloaded from the cBioPortal website2, and subjects with amplification in RRM2B and MYC genes were selected. Presence or absence of these amplifications classified the subjects into four categories: (1) cases with amplification in both RRM2B and MYC, (2) cases with amplification in RRM2B, but not in MYC, (3) cases with amplification in MYC, but not in RRM2B, (4) and cases without amplification in both genes. For each specific cancer type, mutational spectra of each category were calculated by finding the average number of amplifications in each of the 96 mutation classes. To compare differences in these 96 mutation types, one-way ANOVA (Welch, 1951), two-way ANOVA (Fujikoshi, 1993; Shuster et al., 2008), and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Shuster et al., 2008) were used to test for significant differences. In order to eliminate the possibility of false discoveries caused by multiple comparison, in each test, Benjamini–Hochberg correction (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) was applied to each group of 96 p-values (corresponding to 96 mutations). For each cancer type the patients were divided into the following mutation signature groups: (1) cases with amplification in both RRM2B and MYC, (2) cases with amplification in RRM2B, but not in MYC, (3) cases with amplification in MYC, but not in RRM2B, (4) and cases without amplification in both genes, and anova1, anova2 and Wilcoxon rank-sum functions in MATLAB R2018a were used to test for significance. Each signature type was determined to be significant only if its P-value was below 0.05 in the one-way ANOVA test. The two-way ANOVA was used to distinguish the impact of factors such as co-amplifications with MYC. Additionally, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was also performed as a secondary method to test for significance.

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical data was downloaded for the breast cancer (BRCA) TCGA study. Patients were divided into different groups based on having amplifications in RRM2B or MYC, in both or neither. The clinical data from each group were used to generate OS and disease/progression-free survival (DFS) Kaplan-Meier curves (Kaplan and Meier, 1958) using GraphPad Prism 8.0, and each curve was compared with the other respective curves using the log-rank test (Mantel, 1966) and significance was shown based on ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Additionally, Wilcoxon tests were also used (Hazra and Gogtay, 2017), and significance was shown based on ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Analysis of Amplifications in 8q-Genes

The tumors that were assessed for alteration frequency were also analyzed for amplifications in the 8q-genes. Tumor data was downloaded on 6/22/18 from cbioportal.org. The genes used for analysis are located on chromosome 8 from the region 8q11.2–8q24.3 and have been associated with cancer according to the Cancer Index4. The amplification pattern of other 8q-genes in BC, OC, and HNSCC was compared to cases with co-amplifications of MYC and RRM2B, cases with single amplifications or cases that were unaltered. A univariate analysis was conducted to calculate the positive or negative linear trend for the frequency of gene amplification, assessed at 95% confidence interval. The Pearson correlation coefficient and p-values were computed by using PROC CORR in SAS 9.4. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Protein Interaction and Pathway Enrichment

Data for the RRM2B interaction network was downloaded from the BioGRID database (Oughtred et al., 2019) (10/25/2018) and analyzed by Cytoscape v. 3.6.1 (Shannon et al., 2003). Several interactions were added manually based on literature findings [RRM2B-FOXO3 (Cho et al., 2014), RRM2B-P21 (Xue et al., 2007), RRM2B-TP73 (Tebbi et al., 2015), RRM2B-E2F1 (Qi et al., 2015), RRM2B-MEK2 (Piao et al., 2012)]. WebGestalt (WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit) was used for gene set enrichment analysis to extract biological insights from the genes of interest (Liao et al., 2019). The online WebGestalt tool was used, and an over representation analysis was performed. The enrichment results were prioritized by significant p-values, and FDR thresholds at 0.01.

Results

RRM2B Is Highly Amplified in Multiple Cancers, With an Amplification Frequency Similar to MYC, While Alterations in Other RNR Genes Are Infrequent

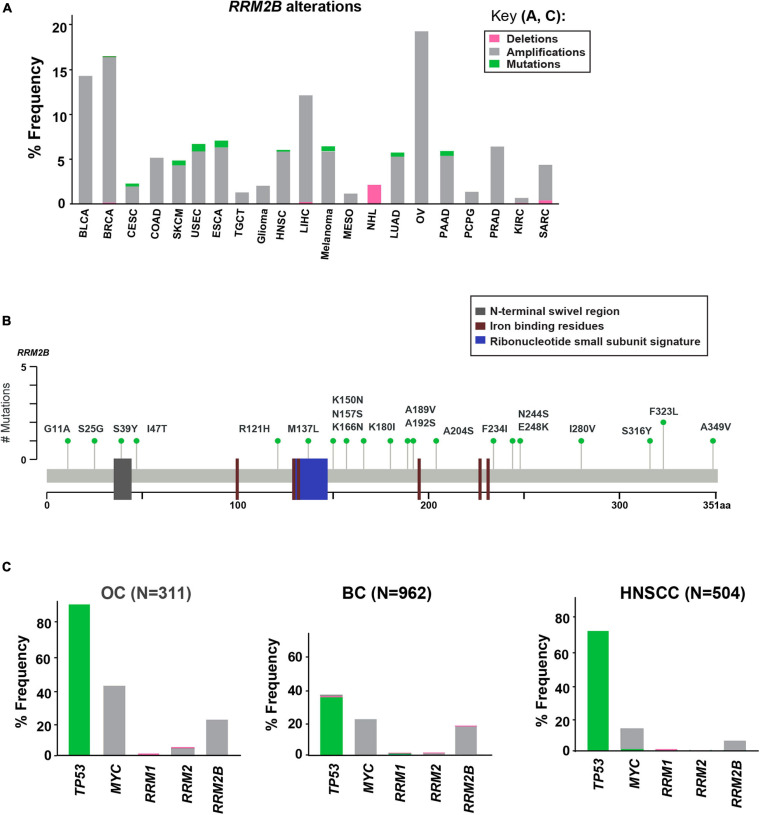

Using cancer cases from TCGA, we observed that RRM2B is frequently amplified, with the highest percentage observed in ovarian, breast, bladder, and liver cancers (21.54–14.5%), and a lower rate of amplifications in multiple other cancers (14–0.6%) (Figure 1A). Deletions of RRM2B were only observed in Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (∼2%). In addition to amplifications, a low frequency of mutations (<2%) were observed in head and neck, lung, endometrial, esophagogastric, cervical, and pancreatic cancers (Figure 1A). Mapping of somatic RRM2B mutations to the RRM2B protein structure indicated the mutations are present in multiple regions of the protein and do not always cluster at defined functional domains/regions (Smith et al., 2009; Maatta et al., 2016; Finsterer and Zarrouk-Mahjoub, 2018), unlike the mutations observed in mitochondrial disorders, which typically result in reduced or eliminated function of the RRM2B protein (Gorman and Taylor, 1993; Bornstein et al., 2008; Figure 1B). Only the R121H mutation found in this study has been previously observed in a patient with mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy (Gorman and Taylor, 1993; Shaibani et al., 2009). This mutation has been predicted to impact the docking interface of the ribonucleoside reductase small subunit homodimer and thereby impact protein activity.

FIGURE 1.

Somatic alterations in RRM2B from cbioportal.org. (A) Somatic alterations in RRM2B across TCGA studies. BLCA, Bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, Breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; COAD, Colon adenocarcinoma; SKCM, Skin cutaneous melanoma; USEC, Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; ESCA, Esophageal carcinoma; TGCT, Testicular germ cell tumors; HNSC, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LIHC, Liver hepatocellular carcinoma; MESO, Mesothelioma; NHL, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; LUAD, Lung adenocarcinoma; OV, Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, Pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PRAD, Prostate adenocarcinoma; KIRC, Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; SARC, Sarcoma. Amplifications (gray), mutations (green), and deletions (pink) are represented as percent frequency. (B) RRM2B mutations in TCGA. 2D RRM2B protein stick figure showing the important domains of RRM2B [N-terminal swivel region, required for dimer stability, gray; ribonucleotide small subunit signature (conserved region in catalytic site between RRM2 and RRM2B), blue, and iron-binding residues required for catalytic activity, red] and the number of somatic mutations in RRM2B. (C) Frequency of TP53, MYC, RRM1, RRM2 and RRM2B alterations in ovarian (OC), breast (BC), and head and neck (HNSCC) cases.

Since RRM2B is regulated by TP53 and is typically co-amplified with MYC (Figure 1), we next compared the frequency of RRM2B alterations with alterations in TP53, and MYC. We also compared the frequency of RRM2B alterations along with the members of the RNR complex [RRM1, RRM2 (Kolberg et al., 2004; Figure 1C)]. For this analysis, we selected breast and ovarian cancer studies as they had the highest frequency of RRM2B alterations. While head and neck cancers carried a lower frequency of amplifications in RRM2B (similar to few other tumor types in Figure 1A), we chose this tumor type because of the clinical significance of TP53 alteration status to HNSCCs (Zhou et al., 2016) and the known regulation of RRM2B by p53. As expected, TP53 was the most altered gene in the studied cancers, however, RRM2B amplifications did not always significantly co-occur with TP53. Interestingly, most cases with TP53 mutations (which were missense, and truncating mutations) did not have RRM2B amplifications (Supplementary Figure 1A). In comparison, a greater number of cases with MYC amplifications were observed to also have RRM2B co-amplifications. For ovarian (OC) and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), this was half of all cases with MYC amplifications, while in breast cancer (BC) this was ∼90% cases (Supplementary Figure 1B). Finally, RRM1 and RRM2, the functional partners of RRM2B, were infrequently altered and did not co-occur with RRM2B amplifications (Figure 1C).

Tumors With RRM2B Amplifications Exhibit Increased RRM2B Expression

Previous studies have not shown whether tumors carrying amplified RRM2B have increased RRM2B expression, which might directly impact its role in cancer. Multiple studies have observed that gene amplifications do not always lead to increased expression (Jia et al., 2016). Thus, to confirm increased expression, we used mRNA expression data from three TCGA studies (OV, BRCA, HNSC), and found that tumors with gains and amplifications had significantly increased RRM2B mRNA expression in all three cancer types studied (Supplementary Figure 2). RRM2B amplifications also significantly correlated with an increase in RRM2B mRNA expression in OC and BC, and with an increased trend in HNSCC (OC: Pearson correlation = 0.64, Log rank p-value = 0.05; BC: Pearson correlation = 0.53, Log rank p-value = 0.04; HNSCC: Pearson correlation = 0.32, Log rank p-value = 0.08) (Supplementary Figure 2).

RRM2B Amplification by Itself or Co-amplification With MYC Is in an 8q-Amplicon That Is Present in Multiple Cancer Types

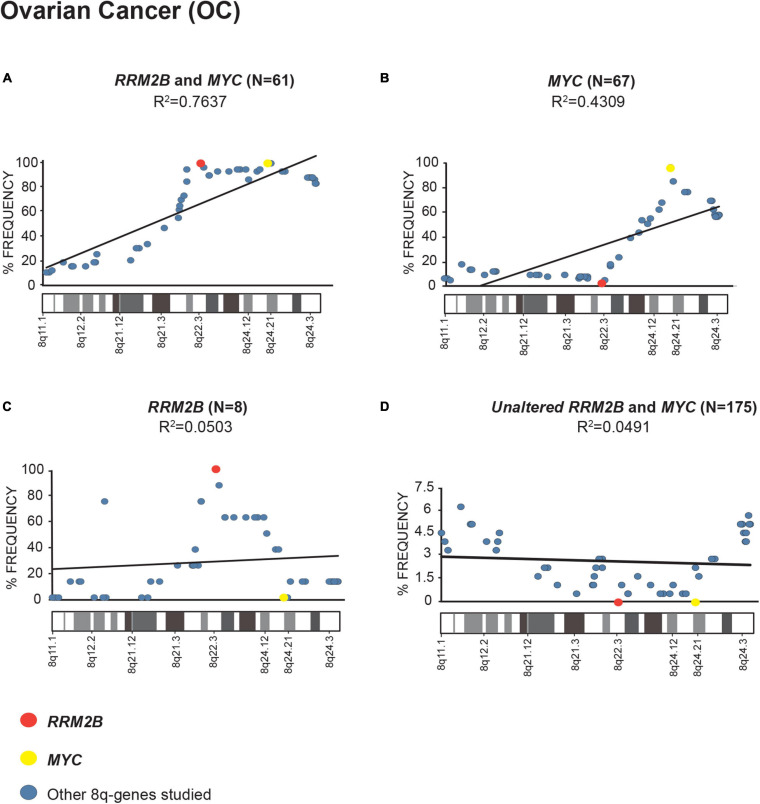

In multiple cancers, we identified that RRM2B and/or MYC were amplified as part of an amplicon with multiple other 8q-genes (Supplementary Table 1, list of cancer relevant genes and gene ontology classification). We queried the amplifications in OC (Figure 2), BC (Supplementary Figure 3), and HNSCC (Supplementary Figure 4) cancers in TCGA.

FIGURE 2.

Amplification frequency of 8q-genes in ovarian cancer (OC). (A) cases with co-amplification of RRM2B and MYC; (B) cases MYC only amplification; (C) cases RRM2B only amplifications; (D) cases with neither (unaltered) were plotted as percent of frequency for amplifications in various 8q-region genes relevant for cancer (see Supplementary Table 1). RRM2B (red circle), MYC (yellow circle), and other genes (blue circle). The Pearson correlation (R2 value) for the data points is represented by a black trend line.

We observed a strong Pearson correlation for amplifications in the 8q11–8q24 region in cases with RRM2B and MYC co-amplifications. The strongest correlation was observed for OC (R2 = 0.7637, p < 0.00001, Figure 2A). The cases with either MYC or RRM2B amplification alone (R2 = 0.4309, p = 0.000273, Figure 2B, and R2 = 0.0.0503, p = 0.905, Figure 2C) or those without (R2 = 0.7637, p = 0.518, Figure 2D) showed weaker Pearson correlation. These amplifications observed (Figures 2A–C) are in the chromosome segment between RRM2B (8q22.3) and MYC (8q24.21). This amplicon contains 11 cancer relevant genes: BALC, ANGPT1, EIF3E, EBAG9, TRSP1, RAD21, EXT1, TNFRSF11B, NOV, HAS2, and RNF139 (Supplementary Table 1).

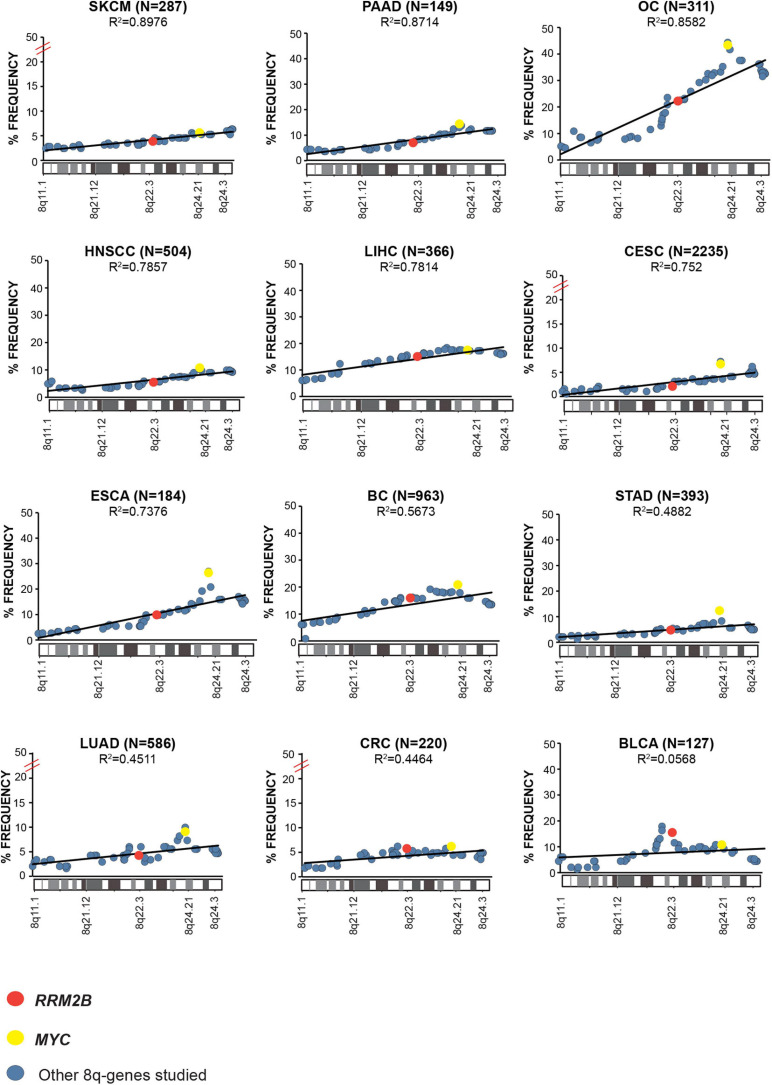

Next, we examined the overall amplification frequency of 8q genes using TCGA data, without segregating cases based on RRM2B and/or MYC amplifications. We found, that the 8q11.3–8q24 amplicon is present in multiple tumor types (Figure 3). A positive correlation was observed for increased amplifications in the 8q11–8q24 region, which includes RRM2B and MYC (Pearson correlation range: R2 = 0.8976–0.0568). The strongest correlations were observed for skin (SKCM, R2 = 0.8976, p < 0.00001), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD, R2 = 0.8714, p < 0.00001), ovarian cancer (OV, R2 = 0.8582, p < 0.00001), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC, R2 = 0.7814, p < 0.00001), and esophageal cancer (ESCA, R2 = 0.7376, p < 0.00001) (Figure 3). All other correlations were significant at p < 0.00001, except for BLCA (p = 0.525). Finally, we also observed that mRNA expression of multiple genes in the amplicon was also significantly increased (Supplementary Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

Amplification frequency of cancer relevant 8q-genes in SKCM, Skin cutaneous melanoma; PAAD, Pancreatic adenocarcinoma; OC, Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; HNSCC, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LIHC, Liver hepatocellular carcinoma; CESC, Cervical and endocervical cancers; ESCA, Esophageal carcinoma; BC, Breast invasive carcinoma; STAD, Stomach adenocarcinoma; LUAD, Lung adenocarcinoma; COAD, Colon adenocarcinoma; BLCA, Bladder urothelial carcinoma, amplifications were plotted as percent of frequency for amplifications. RRM2B (red circle), MYC (yellow circle), and other genes (blue circle). The Pearson correlation (R2 value) for the data points is represented by a black trend line.

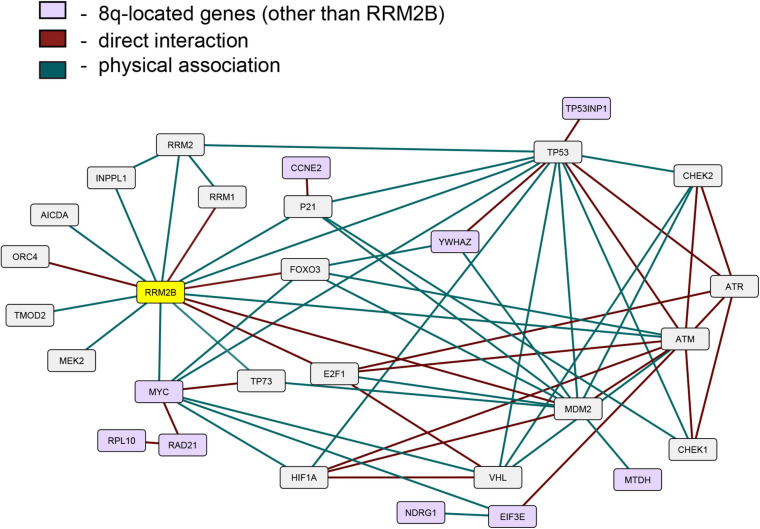

RRM2B Protein Interaction Network Includes Co-amplified 8q-Amplicon Genes

Since the expression of RRM2B, MYC, and several other 8q-amplicon genes was increased, we next tested if the products of these genes within the 8q-amplicon interact with RRM2B. Figure 4 shows that RRM2B interacts with several proteins that are important for cell regulatory mechanisms such as DNA damage and response pathway, cell cycle, oxygen sensing and apoptosis. We also found that several 8q22–24 gene products (Figure 4, in light purple) also interact or intersect with the proteins in the RRM2B network. Finally, we performed a pathway enrichment analysis for all the interacting genes presented in Figure 4. Using WebGestalt tool (Liao et al., 2019), we found that the most significantly enriched pathways were signal transduction mediated by p53, response to DNA damage and other environmental stimuli, cell cycle checkpoints, DNA replication, response to oxygen levels and apoptotic signaling. The results are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Overall, these data suggest that amplifications in the 8q-region, observed in multiple cancers, may impact cancer cell survival due to their involvement and intersection in important cellular pathways.

FIGURE 4.

An interactive network of RRM2B and related genes. The network represents proteins that functionally interact or intersect with RRM2B (yellow) or other 8q-gene products (purple). Red lines represent direct interaction, and green lines—physical association (interactions classified according to the BioGRID database annotation).

RRM2B-Amplified Tumors Exhibit Distinct Tumor Mutation Signatures

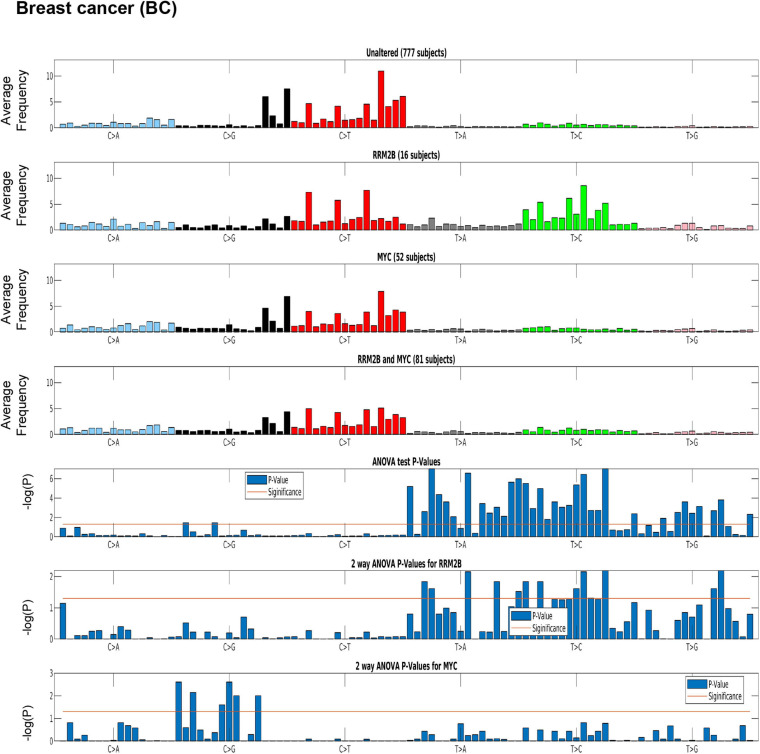

Distinct tumor mutation signatures have been associated with defects in certain genes or pathways, and with certain endogenous and exogenous exposures (Alexandrov et al., 2020). Here, we tested whether RRM2B amplifications are associated with specific tumor mutational signatures. For this analysis, we used the recent PanCancer Atlas data, reporting mutational spectra for 9493 individual tumors, including 926 BC, 384 OC, and 461 HNSCC and 524 LUAD (Alexandrov et al., 2020). Interestingly, BC cases with RRM2B amplification alone were significantly associated with T > C and T > A mutations (P < 0.05, Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 4).

FIGURE 5.

Mutation signature in breast cancer (BC) cases segregated by amplification type. One-way ANOVA (RRM2B amplifications only vs. other groups) and two-way ANOVA (included group with RRM2B and MYC co-amplifications) analysis showed that the T > C and T > G mutations are statistically significant. Top panels: tumor whole-exome sequence data from the PanCancer Atlas studies was used to calculate the average frequency of the 96 trinucleotide context mutations in each group: unaltered cases, cases with only RRM2B amplifications, cases with only MYC amplifications, and cases with amplifications in both. Bottom panels: The statistical significance of each comparisons is represented by ANOVA tests as -log10 (P-value) for each of the 96 trinucleotide context mutations. The -log10 (P) visualizations are provided for: one-way ANOVA comparing RRM2B only group to all other groups, a two-way ANOVA comparing all groups with RRM2B or MYC amplifications. -log10 (P)—the taller the bars are, the lower is the P-value and when the bars exceed the red line, P-values are less than 5%. P-values of each subfigure have been corrected using Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

A similar signature was observed in HNSCC, but not in OC (Supplementary Figure 5). The HNSCC and OC signatures could not be tested for significance as only few cases were present in the PanCancer Atlas data. For LUAD, a distinct signature of C > A mutations (significant by one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA tests as above, p < 0.05; Supplementary Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 4) was observed for cases with only RRM2B amplifications.

The observed mutation signatures for RRM2B amplifications were most similar to those that have been recently described for defects in distinct DNA replication and repair pathways (Alexandrov et al., 2020). The tumor mutation signatures observed have been associated with defective DNA base excision repair, and DNA mismatch repair. We also observed mutation signatures for presence of reactive oxygen species that can lead to extensive DNA base damage (Cadet and Wagner, 2013).

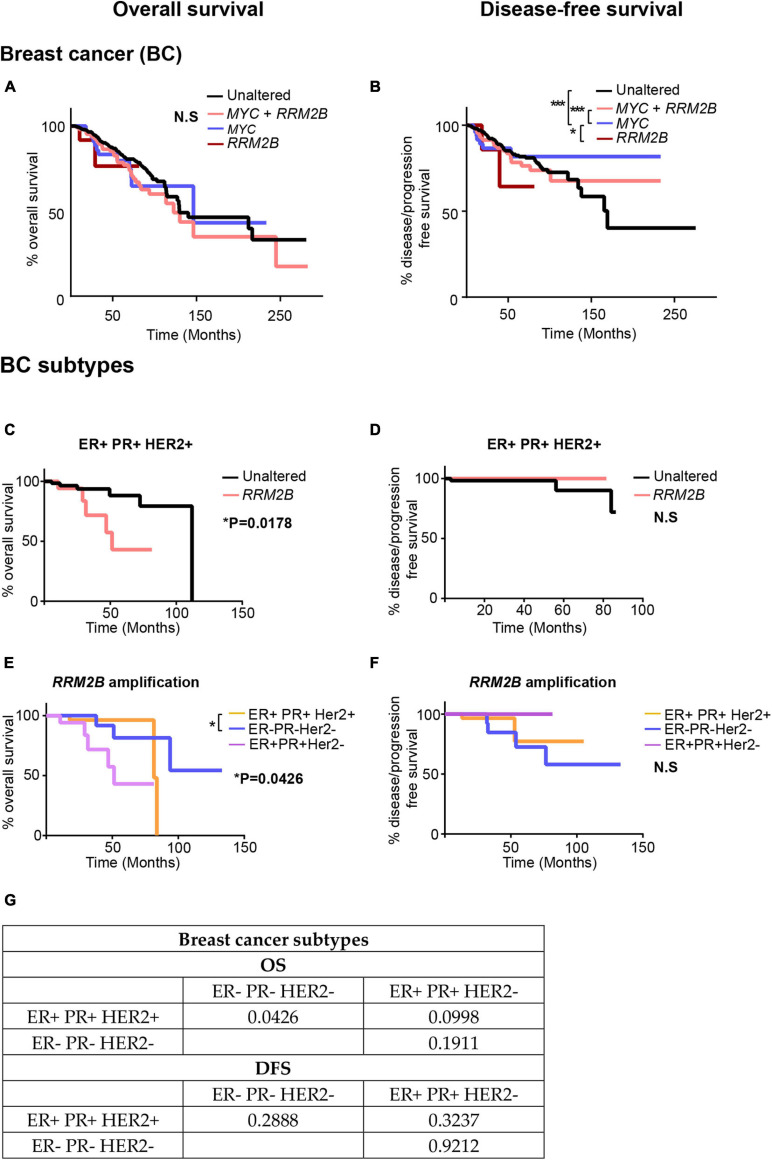

RRM2B Amplifications Correlate With Clinical Outcome in ER + PR + HER2 + Breast Cancer

Based on the distinct tumor signatures observed in RRM2B-amplified breast cancers (Figure 6), we next tested whether RRM2B-amplifications associate with clinical outcomes. In BC, no significant differences in OS were observed (Figure 6A), which is different from a previous finding in breast cancer (Chae et al., 2016). However, in comparison to OS, significant differences were observed for DFS (Figure 6B). MYC amplification alone had the best DFS, compared to MYC and RRM2B co-amplified cases, and unaltered cases (p < 0.0001). Additionally, RRM2B amplification cases tend to have worse DFS than MYC only cases (p = 0.0519).

FIGURE 6.

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS and DFS in breast cancer (BC) (A,B) and its subtypes (C–G) studies with RRM2B amplifications and/or MYC amplifications. (A) OS in BC cases. The cases that were unaltered for both genes (black, n = 737), cases with RRM2B amplifications (red, n = 14), cases with MYC amplifications (blue, n = 62) and co-amplifications (pink, n = 210) were plotted. (B) DFS in BC cases. The cases that were unaltered for both genes (black, n = 678), cases with RRM2B amplifications (red, n = 12), cases with MYC amplifications (blue, n = 55) and co-amplifications (pink, n = 184) were plotted. (C) OS in ER + PR + HER2 + BC cases. The cases that were unaltered for RRM2B (black, n = 68), cases with RRM2B amplifications (salmon, n = 18). (D) DFS in ER + PR + HER2 + cases. The cases that were unaltered for RRM2B (black, n = 63), cases with RRM2B amplifications (red, n = 13). (E) OS in BC subtypes with RRM2B amplifications. ER + PR + HER2 + cases with amplifications in RRM2B (purple, n = 18), ER- PR- HER2- cases with amplifications in RRM2B (blue, n = 26), and ER + PR + HER2- cases with amplifications in RRM2B (peach, n = 36). (F) DFS in BC subtypes with RRM2B amplifications. ER + PR + HER2 + cases with amplifications in RRM2B (purple, n = 13), ER- PR- HER2- cases with amplifications in RRM2B (blue, n = 25), and ER + PR + HER2- cases with amplifications in RRM2B (peach, n = 34). The plots were compared using Log-rank test and significance is shown as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (G) P-values for the graphs (E,F).

To further explore the conflicting findings in BC, we analyzed RRM2B amplifications separately in each of the three major subtypes of breast cancer [ER + PR + HER2 + (n = 86), ER + PR + HER2- (n = 334), and triple negative ER-PR-HER2- (n = 100)]. We observed that patients with ER + PR + HER2 + BC bearing RRM2B amplifications had a significant decrease in OS (p = 0.0178, Figures 6C,E), with no difference in DFS (Figures 6D,F). Additionally, when comparing OS in all three BC subtypes with RRM2B amplifications, ER + PR + HER2 + patients (n = 18) had significantly worse OS than ER- PR- HER2- patients (n = 26) (p = 0.0426). The previous studies that observed worse OS in BC, based on RRM2B amplification, did not consider subtype differences, and may have only included the major BC subtype (ER + PR + HER2 +). Additionally, p-values for all comparisons (log-rank test and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test) in all the above BCs are available in Supplementary Tables 5, 6.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that RRM2B, which is a major downstream target of p53, is highly amplified across multiple tumor types. Frequent RRM2B amplifications are a contrast to TP53 loss of function mutations or deletions that are typically found in tumors. We found that RRM2B, which is present on chromosome 8, is usually co-amplified with MYC oncogene (which is also on chromosome 8). We also found, in multiple cancers, that tumors with co-amplified RRM2B and MYC exhibit significant amplification of the 8q22.3–8q24 region of chromosome 8. Intriguingly, we observed that several genes within the 8q-amplicon also interact with the RRM2B-functional network. Pathway enrichment analysis suggests the importance of 8q-region genes in response to oxygen levels, DNA replication, cell cycle, and DNA damage response.

We found that several gene products of the 8q22–24 region also interact or intersect with proteins in the RRM2B network. YWHAZ, an 8q-protein in the RRM2B network, binds and retains phosphorylated FOXO3 in the cytoplasm preventing its activity as a transcription factor, and apoptosis (Brunet et al., 1999). Under DNA damaging conditions, it has been shown that ATM-dependent activation of p53 leads to the formation of a binding site for YWHAZ, thus, increasing the affinity of p53 to bind with regulatory parts of cell cycle genes such as CDKN1A, GADD45, MDM2 (Chernov and Gr, 1997). EIF3E, another 8q-protein in the RRM2B network, interacts with ATM and BRCA1 for the execution of DNA damage response and EIF3E alterations have been previously observed in breast cancer (Morris et al., 2012). These results suggest further investigation in cellular models to validate relationships between RRM2B, MYC and the identified interacting proteins. These data also suggest that amplifications in the 8q-region could have a profound effect on regulatory pathways such as DNA damage response and repair, cell cycle and oxygen sensing. It is well-appreciated that these regulatory pathways majorly impact response to cancer therapies and thereby clinical outcomes (Olcina et al., 2010; Luoto et al., 2013; O’Connor, 2015; Scanlon and Glazer, 2015; Ng et al., 2018; Begg and Tavassoli, 2020; Huang and Zhou, 2020); further warranting studies in cellular models of cancer.

The analysis of clinical outcomes in breast cancer revealed that based on the cancer subtype, co-alteration of RRM2B with MYC, or alone may significantly impact patient outcomes. The clinical implications of these data will be further illuminated by (a) a larger sample size of RRM2B-only amplified tumors and more balanced number of samples across each category, (b) analysis of outcomes in other cancers, and (c) other independent prognostic factors of overall survival. A previous study in breast cancer found frequent MYC co-amplifications with multiple genes in the 8q chromosomal region (Parris et al., 2014). This study concluded that these co-amplifications may explain the aggressive phenotypes of these tumors (Parris et al., 2014). MYC was found to be one of the most amplified genes in high-grade ovarian serous carcinomas, and the patients bearing MYC-amplified tumors had better overall survival (Macintyre et al., 2018). However, this study did not extend the analysis to other genes on chromosome 8. A recent study on therapeutic resistance in the highly heterogenous ovarian serous grade carcinomas consistently found amplifications in the 8q-region (starting from 8q22.3) in biopsies from different regions of the tumor, and the relapsed tumor tissue (Ballabio et al., 2019). These data suggest potential clinical significance of amplifications in the 8q-region. While MYC is the main driver for these tumors, the amplification RRM2B and the other 8q-genes may be relevant for cancer cell survival, with therapeutic implications.

Mutation signature analysis revealed that RRM2B-amplified tumors carry defects in distinct DNA repair pathways (base excision repair, DNA mismatch repair), and oxidative DNA damage. A previous study in mice found that overexpression of RRM genes combined with defective mismatch repair can lead to mutagenesis, and carcinogenesis (Xu et al., 2008). While a regulated expression of RRM2B reduces oxidative stress in a p53-dependent manner (Kuo et al., 2012), the impact of RRM2B overexpression on the levels of reactive oxygen species is not known. The observation of mutation signatures associated with increased reactive oxygen species suggests that RRM2B overexpression may impede the oxidative stress or oxygen sensing pathway. Finally, these observed mutation signatures suggest therapies that target defective DNA repair, such as PARP inhibitor therapy, may lead to clinical benefit in patients with RRM2B-amplified tumors (O’Connor, 2015; Nickoloff et al., 2017; Desai et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2018).

Alterations in genes involved in DNA replication and/or repair, and DNA damage response pathways are known to increase genetic instability, and lead to cancer (Chae et al., 2016). RRM2B is essential for DNA replication (nuclear and mitochondrial), DNA damage response and repair, protection from oxidative damage, and overall maintenance of genetic stability. Despite these known functions, the current understanding of RRM2B is limited to its role in MDS. Overall, in this study we provide an in silico analysis of RRM2B alterations in cancer and their potential significance. Further studies in cellular models are warranted to delineate the role of RRM2B, and other 8q-chromosome genes in cancer cell maintenance, therapeutic targeting and clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Overall, this study provides an in-depth analysis of RRM2B alterations in multiple tumor types, majorly reflected as RRM2B amplifications in conjunction with MYC, and other genes on chromosome 8. These cases exhibit a distinct 8q-amplification pattern as well as survival outcome differences and mutation signature differences, depending on cancer type and subtypes. Future genome-wide studies of other cancer datasets are warranted to confirm the results of the present study. Finally, studies in cellular models are required to delineate the role of RRM2B, and other 8q-chromosome genes in cancer cell maintenance, therapeutic targeting and clinical outcomes.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: www.cbioportal.org.

Author Contributions

WI and ED: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, roles, writing—original draft, data curation, visualization, and validation. SS: formal analysis, investigation, roles, writing—original draft, and data curation. TV: software, formal analysis, and data curation, and visualization. GR: writing—review and editing, methodology, supervision, and funding acquisition. SA: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, resources, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are express gratitude to Dr. Erica Golemis at the Fox Chase Cancer Center for many helpful discussions and advice with this work.

Funding. WI was supported by the Fox Chase Cancer Center Risk Assessment Program Funds and NSF #1650531 (to GR), SA and ED were supported by the DOD W81XWH-18-1-0148 (to SA). TV and GR were supported by the NSF #1650531 (to GR).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.628758/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alexandrov L. B., Kim J., Haradhvala N. J., Huang M. N., Tian Ng A. W., Wu Y., et al. (2020). The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 578 94–101. 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aye Y., Li M., Long M. J., Weiss R. S. (2015). Ribonucleotide reductase and cancer: biological mechanisms and targeted therapies. Oncogene 34 2011–2021. 10.1038/onc.2014.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio S., Craparotta I., Paracchini L., Mannarino L., Corso S., Pezzotta M. G., et al. (2019). Multisite analysis of high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancers identifies genomic regions of focal and recurrent copy number alteration in 3q26.2 and 8q24.3. Int. J. Cancer 145 2670–2681. 10.1002/ijc.32288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg K., Tavassoli M. (2020). Inside the hypoxic tumour: reprogramming of the DDR and radioresistance. Cell Death Discov. 6:77. 10.1038/s41420-020-00311-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 57 289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal E., Vassallo K., Toppmeyer D., Barnard N., Rye I. H., Almendro V., et al. (2012). Amplified loci on chromosomes 8 and 17 predict early relapse in ER-positive breast cancers. PLoS One 7:e38575. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein B., Area E., Flanigan K. M., Ganesh J., Jayakar P., Swoboda K. J., et al. (2008). Mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome due to mutations in the RRM2B gene. Neuromuscul. Disord. 18 453–459. 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch J., Wohr G., Hautmann R., Mattfeldt T., Bruderlein S., Moller P., et al. (1998). Chromosomal changes during progression of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and delineation of the amplified interval on chromosome arm 8q. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 23 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A., Bonni A., Zigmond M. J., Lin M. Z., Juo P., Hu L. S., et al. (1999). Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 96 857–868. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne J. A., Balleine R. L., Schoenberg Fejzo M., Mercieca J., Chiew Y. E., Livnat Y., et al. (2005). Tumor protein D52 (TPD52) is overexpressed and a gene amplification target in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 117 1049–1054. 10.1002/ijc.21250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J., Wagner J. R. (2013). DNA base damage by reactive oxygen species, oxidizing agents, and UV radiation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a012559. 10.1101/cshperspect.a012559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E., Gao J., Dogrusoz U., Gross B. E., Sumer S. O., Aksoy B. A., et al. (2012). The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2 401–404. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae Y. K., Anker J. F., Carneiro B. A., Chandra S., Kaplan J., Kalyan A., et al. (2016). Genomic landscape of DNA repair genes in cancer. Oncotarget 7 23312–23321. 10.18632/oncotarget.8196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Xiao Y., Cai X., Liu J., Chen K., Zhang X. (2017). Overexpression of p53R2 is associated with poor prognosis in lung sarcomatoid carcinoma. BMC Cancer 17:855. 10.1186/s12885-017-3811-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernov M. V., Gr S. (1997). The p53 activation and apoptosis induced by DNA damage are reversibly inhibited by salicylate. Oncogene 14 2503–2510. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E. C., Kuo M. L., Liu X., Yang L., Hsieh Y. C., Wang J., et al. (2014). Tumor suppressor FOXO3 regulates ribonucleotide reductase subunit RRM2B and impacts on survival of cancer patients. Oncotarget 5 4834–4844. 10.18632/oncotarget.2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph F., Schmidt B., Schmitz-Drager B. J., Schulz W. A. (1999). Over-expression and amplification of the c-myc gene in human urothelial carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 84 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A., Yan Y., Gerson S. L. (2018). Advances in therapeutic targeting of the DNA damage response in cancer. DNA Repair 66–67 24–29. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers J. P., Worley L., Onken M. D., Harbour J. W. (2005). DDEF1 is located in an amplified region of chromosome 8q and is overexpressed in uveal melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 11 3609–3613. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer J., Zarrouk-Mahjoub S. (2018). Phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of RRM2B variants. Neuropediatrics 49 231–237. 10.1055/s-0037-1609039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foskolou I. P., Hammond E. M. (2017). RRM2B: an oxygen-requiring protein with a role in hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 4:e1335272. 10.1080/23723556.2017.1335272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foskolou I. P., Jorgensen C., Leszczynska K. B., Olcina M. M., Tarhonskaya H., Haisma B., et al. (2017). Ribonucleotide reductase requires subunit switching in hypoxia to maintain DNA replication. Mol. Cell 66 206–220.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikoshi Y. (1993). Two-way ANOVA models with unbalanced data. Discrete Math. 116 315–334. 10.1016/0012-365X(93)90410-U [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Song P. X. (2005). Nonparametric tests for differential gene expression and interaction effects in multi-factorial microarray experiments. BMC Bioinformatics 6:186. 10.1186/1471-2105-6-186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman G. S., Taylor R. W. (1993). “RRM2B-related mitochondrial disease,” in GeneReviews(®), eds Adam M. P., Ardinger H. H., Pagon R. A., Wallace S. E., Bean L. J. H., Stephens K., et al. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington; ). [Google Scholar]

- Hazra A., Gogtay N. (2017). Biostatistics series module 9: survival analysis. Indian J. Dermatol. 62 251–257. 10.4103/ijd.IJD_201_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J. C., Cheung S. T., Patil M., Chen X., Fan S. T. (2006). Increased expression of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor attachment protein 1 (GPAA1) is associated with gene amplification in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 119 1330–1337. 10.1002/ijc.22005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. X., Zhou P. K. (2020). DNA damage response signaling pathways and targets for radiotherapy sensitization in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5:60. 10.1038/s41392-020-0150-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y., Chen L., Jia Q., Dou X., Xu N., Liao D. J. (2016). The well-accepted notion that gene amplification contributes to increased expression still remains, after all these years, a reasonable but unproven assumption. J. Carcinog. 15:3. 10.4103/1477-3163.182809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkat M., De Melo J., Hickman K. A., Lourenco C., Redel C., Resetca D., et al. (2017). MYC deregulation in primary human cancers. Genes (Basel) 8:151. 10.3390/genes8060151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E. L., Meier P. (1958). Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 53 457–481. 10.2307/2281868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karl P., Francis G. (1997). Note on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 58 240–242. 10.1098/rspl.1895.0041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolberg M., Strand K. R., Graff P., Andersson K. K. (2004). Structure, function, and mechanism of ribonucleotide reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1699 1–34. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M. L., Sy A. J., Xue L., Chi M., Lee M. T., Yen T., et al. (2012). RRM2B suppresses activation of the oxidative stress pathway and is up-regulated by p53 during senescence. Sci. Rep. 2:822. 10.1038/srep00822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M. J., Kim R. N., Song K., Jeon S., Jeong H. M., Kim J. S., et al. (2017). Genes co-amplified with ERBB2 or MET as novel potential cancer-promoting genes in gastric cancer. Oncotarget 8 92209–92226. 10.18632/oncotarget.21150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Tibshirani R. (2013). Finding consistent patterns: a nonparametric approach for identifying differential expression in RNA-Seq data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 22 519–536. 10.1177/0962280211428386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Wang J., Jaehnig E. J., Shi Z., Zhang B. (2019). WebGestalt 2019: gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 W199–W205. 10.1093/nar/gkz401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Lai L., Wang X., Xue L., Leora S., Wu J., et al. (2011). Ribonucleotide reductase small subunit M2B prognoses better survival in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 71 3202–3213. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoto K. R., Kumareswaran R., Bristow R. G. (2013). Tumor hypoxia as a driving force in genetic instability. Genome Integr. 4:5. 10.1186/2041-9414-4-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Setton J., Lee N. Y., Riaz N., Powell S. N. (2018). The therapeutic significance of mutational signatures from DNA repair deficiency in cancer. Nat. Commun. 9:3292. 10.1038/s41467-018-05228-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maatta K., Rantapero T., Lindstrom A., Nykter M., Kankuri-Tammilehto M., Laasanen S. L., et al. (2016). Whole-exome sequencing of Finnish hereditary breast cancer families. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25 85–93. 10.1038/ejhg.2016.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre G., Goranova T. E., De Silva D., Ennis D., Piskorz A. M., Eldridge M., et al. (2018). Copy number signatures and mutational processes in ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 50 1262–1270. 10.1038/s41588-018-0179-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. (1966). Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother. Rep. 50 163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C., Tomimatsu N., Richard D. J., Cluet D., Burma S., Khanna K. K., et al. (2012). INT6/EIF3E interacts with ATM and is required for proper execution of the DNA damage response in human cells. Cancer Res. 72 2006–2016. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng N., Purshouse K., Foskolou I. P., Olcina M. M., Hammond E. M. (2018). Challenges to DNA replication in hypoxic conditions. FEBS J. 285 1563–1571. 10.1111/febs.14377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff J. A., Jones D., Lee S. H., Williamson E. A., Hromas R. (2017). Drugging the cancers addicted to DNA repair. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109:djx059. 10.1093/jnci/djx059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M. J. (2015). Targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Mol. Cell 60 547–560. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura H., Natsugoe S., Matsumoto M., Mataki Y., Takatori H., Ishigami S., et al. (2005). The predictive value of p53, p53R2, and p21 for the effect of chemoradiation therapy on oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 92 284–289. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura H., Natsugoe S., Yokomakura N., Kita Y., Matsumoto M., Uchikado Y., et al. (2006). Expression of p53R2 is related to prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 12 3740–3745. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcina M., Lecane P. S., Hammond E. M. (2010). Targeting hypoxic cells through the DNA damage response. Clin. Cancer Res. 16 5624–5629. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-10-0286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oughtred R., Stark C., Breitkreutz B. J., Rust J., Boucher L., Chang C., et al. (2019). The BioGRID interaction database: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 D529–D541. 10.1093/nar/gky1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parris T. Z., Kovacs A., Hajizadeh S., Nemes S., Semaan M., Levin M., et al. (2014). Frequent MYC coamplification and DNA hypomethylation of multiple genes on 8q in 8p11-p12-amplified breast carcinomas. Oncogenesis 3:e95. 10.1038/oncsis.2014.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao C., Youn C. K., Jin M., Yoon S. P., Chang I. Y., Lee J. H., et al. (2012). MEK2 regulates ribonucleotide reductase activity through functional interaction with ribonucleotide reductase small subunit p53R2. Cell Cycle 11 3237–3249. 10.4161/cc.21591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi J. J., Liu L., Cao J. X., An G. S., Li S. Y., Li G., et al. (2015). E2F1 regulates p53R2 gene expression in p53-deficient cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 399 179–188. 10.1007/s11010-014-2244-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Bardelli A., Buckhaults P., Velculescu V. E., Rago C., St Croix B., et al. (2001). A phosphatase associated with metastasis of colorectal cancer. Science 294 1343–1346. 10.1126/science.1065817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Qian J., Slezak J. M., Lieber M. M., Bostwick D. G., Bergstralh E. J., et al. (1999). Clinical significance of alterations of chromosome 8 in high-grade, advanced, nonmetastatic prostate carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91 1574–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon S. E., Glazer P. M. (2015). Multifaceted control of DNA repair pathways by the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. DNA Repair (Amst.) 32 180–189. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher C., Poremba C., Wolters H., Schafer K. L., Senninger N., Colombo-Benkmann M. (2007). Gain of chromosome 8q: a potential prognostic marker in resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 14 1327–1335. 10.1245/s10434-006-9113-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaibani A., Shchelochkov O. A., Zhang S., Katsonis P., Lichtarge O., Wong L. J., et al. (2009). Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy due to mutations in RRM2B. Arch. Neurol. 66 1028–1032. 10.1001/archneurol.2009.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 2498–2504. 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster J. J., Theriaque D. W., Ilfeld B. M. (2008). Applying Hodges-Lehmann scale parameter estimates to hospital discharge times. Clin. Trials 5 631–634. 10.1177/1740774508098327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P., Zhou B., Ho N., Yuan Y. C., Su L., Tsai S. C., et al. (2009). 2.6 A X-ray crystal structure of human p53R2, a p53-inducible ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry 48 11134–11141. 10.1021/bi9001425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Arakawa H., Yamaguchi T., Shiraishi K., Fukuda S., Matsui K., et al. (2000). A ribonucleotide reductase gene involved in a p53-dependent cell-cycle checkpoint for DNA damage. Nature 404 42–49. 10.1038/35003506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbi A., Guittet O., Tuphile K., Cabrie A., Lepoivre M. (2015). Caspase-dependent proteolysis of human ribonucleotide reductase small subunits R2 and p53R2 during Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 290 14077–14090. 10.1074/jbc.M115.649640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Liu X., Xue L., Zhang K., Kuo M. L., Hu S., et al. (2011). Ribonucleotide reductase subunit p53R2 regulates mitochondria homeostasis and function in KB and PC-3 cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 410 102–107. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch B. L. (1951). On the comparison of several mean values: an alternative approach. Biometrika 38 330–336. 10.2307/2332579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Page J. L., Surtees J. A., Liu H., Lagedrost S., Lu Y., et al. (2008). Broad overexpression of ribonucleotide reductase genes in mice specifically induces lung neoplasms. Cancer Res. 68 2652–2660. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L., Zhou B., Liu X., Heung Y., Chau J., Chu E., et al. (2007). Ribonucleotide reductase small subunit p53R2 facilitates p21 induction of G1 arrest under UV irradiation. Cancer Res. 67 16–21. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanamoto S., Kawasaki G., Yoshitomi I., Mizuno A. (2003). Expression of p53R2, newly p53 target in oral normal epithelium, epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 190 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong Z. W., Zaini Z. M., Kallarakkal T. G., Karen-Ng L. P., Rahman Z. A., Ismail S. M., et al. (2014). Genetic alterations of chromosome 8 genes in oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 4:6073. 10.1038/srep06073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Liu Z., Myers J. N. (2016). TP53 mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their impact on disease progression and treatment response. J. Cell. Biochem. 117 2682–2692. 10.1002/jcb.25592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: www.cbioportal.org.