Abstract

Background

Numerous implementation strategies to improve utilization of statins in patients with hypercholesterolemia have been utilized, with varying degrees of success. The aim of this systematic review is to determine the state of evidence of implementation strategies on the uptake of statins.

Methods and results

This systematic review identified and categorized implementation strategies, according to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation, used in studies to improve statin use. We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to October 2018. All included studies were reported in English and had at least one strategy to promote statin uptake that could be categorized using the ERIC compilation. Data extraction was completed independently, in duplicate, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. We extracted LDL-C (concentration and target achievement), statin prescribing, and statin adherence (percentage and target achievement). A total of 258 strategies were used across 86 trials. The median number of strategies used was 3 (SD 2.2, range 1–13). Implementation strategy descriptions often did not include key defining characteristics: temporality was reported in 59%, dose in 52%, affected outcome in 9%, and justification in 6%. Thirty-one trials reported at least 1 of the 3 outcomes of interest: significantly reduced LDL-C (standardized mean difference [SMD] − 0.17, 95% CI − 0.27 to − 0.07, p = 0.0006; odds ratio [OR] 1.33, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.58, p = 0.0008), increased rates of statin prescribing (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.60 to 3.06, p < 0.0001), and improved statin adherence (SMD 0.13, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.19; p = 0.0002; OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.63, p = 0.023). The number of implementation strategies used per study positively influenced the efficacy outcomes.

Conclusion

Although studies demonstrated improved statin prescribing, statin adherence, and reduced LDL-C, no single strategy or group of strategies consistently improved outcomes.

Trial registration

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13012-021-01108-0.

Keywords: Statin, Hypercholesterolemia, Implementation strategies, Uptake, Meta-analysis

Contributions to the literature.

A variety of implementation strategies have been used to promote statin uptake.

Lack of generalizability of implementation strategies to improve statin use is due in part to lack of detailed reporting of these strategies in the literature.

No single implementation strategy appears to be associated with improved outcomes when compared with others.

Multiple implementation strategies are likely to be required to improve statin utilization.

Introduction

Statin medications reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) blood concentrations and cardiovascular events in patients with hypercholesterolemia, and guidelines recommend statin therapy to lower LDL-C in patients who are at risk for developing or have known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [1]. Despite evidence for the benefits of statins, the medications are widely underutilized [2–6]. Previous studies highlight both patient- and prescriber-barriers to statin use including side effects, competing medical conditions, busy clinics, and patient reluctance affecting adherence to prescribed medications [7–9]. Lack of adherence is associated with increased mortality in a dose dependent relationship [10].

Implementation strategies can be used to promote the uptake of interventions, such as statin therapy, and are defined as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice” [11]. Numerous implementation strategies have been attempted to improve utilization of statins, all with varying degrees of success. These studies have targeted a variety of actors (e.g., patients, clinicians, or systems) and employed a variety of implementation strategies (e.g., education, reminders, or financial incentives). A computer-based clinical decision support system to aid in prescribing of evidence-based treatment for hyperlipidemia, which targeted clinicians, was found to significantly reduce blood LDL-C concentrations [12]. However, when providing financial incentives to providers, patients, or both, a study found that only the combination incentive was successful in reducing LDL-C levels to target [13]. The absolute and comparative effectiveness of these strategies, however, is unclear. Knowing which strategies are most effective can facilitate the uptake of statins and lead to reduce mortality.

To address this issue, we aimed to address the following key questions:

What implementation strategies have been used to promote the uptake of statins?

How completely are the implementation strategies utilized reported in studies designed to promote statin uptake?

Which implementation strategy, or combination of strategies, is (are) the most effective at promoting the uptake of statins?

We conducted a systematic review of studies aimed at improving statin use and categorized implementation strategies by the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation [14]. Our primary objective was to better understand the impact of specific implementation strategies on the utilization of statins in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Our secondary objective was to evaluate statin adherence, statin prescribing, and lowering of LDL-C after intervention.

Methods

This registered (PROSPERO CRD42018114952) systematic review adhered to the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [15].

Search strategy

A medical librarian (L.H.Y.) searched the literature for records including the concepts of hypercholesterolemia, hyperlipidemia, and statins. The search strategies used a combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary and searched the following databases from inception to October 2018: MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Clinicaltrials.gov. References were imported into Endnote™ and duplicates were identified and removed. An example of the search string can be found in Table 1 and the fully reproducible search strategies for each database can be found in Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Table 1.

Example search string

| Database | Search string |

|---|---|

| Embase | ('hypercholesterolemia'/exp OR 'familial hypercholesterolemia'/exp OR hypercholesterolemia:ti,ab,kw OR cholesteremia:ti,ab,kw OR cholesterinemia:ti,ab,kw OR cholesterolemia:ti,ab,kw OR hypercholesteremia:ti,ab,kw OR hypercholesterinaemia:ti,ab,kw OR hypercholesterinemia:ti,ab,kw OR hypercholesterolaemia:ti,ab,kw OR (('high cholesterol' NEAR/1 level*):ti,ab,kw) OR ((elevated NEAR/1 cholesterol*):ti,ab,kw) OR 'hyperlipidemia'/exp OR 'familial hyperlipemia'/exp OR hyperlipemia*:ti,ab,kw OR hyperlipaemia:ti,ab,kw OR hyperlipemia:ti,ab,kw OR hyperlipidaemia:ti,ab,kw OR hyperlipidaemias:ti,ab,kw OR hyperlipidemias:ti,ab,kw OR hyperlipidemic:ti,ab,kw OR lipaemia:ti,ab,kw OR lipemia:ti,ab,kw OR lipidaemia:ti,ab,kw OR lipidemia:ti,ab,kw) AND ('hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor'/exp OR 'hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor':ti,ab,kw OR 'hydroxymethylglutaryl-coa inhibitors':ti,ab,kw OR 'hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme a inhibitors':ti,ab,kw OR 'hmg coa reductase inhibitor':ti,ab,kw OR 'hmg coenzyme a reductase inhibitor':ti,ab,kw OR 'hmg coa reductase inhibitors':ti,ab,kw OR 'hydroxymethylglutaryl coa reductase inhibitors':ti,ab,kw OR 'hydroxymethylglutaryl-coa reductase inhibitors':ti,ab,kw OR statin:ti,ab,kw OR statins:ti,ab,kw OR vastatin:ti,ab,kw) |

Study selection

We included studies reported in English, regardless of the country where the study was conducted, that had at least one strategy promoting statin uptake that could be categorized using the ERIC compilation [14, 16]. Seven manuscripts were excluded for this reason. The ERIC compilation was created so that researchers have a standardized way to name, define, and categorize implementation strategies. The ERIC compilation was selected for use in this review because the implementations strategies in the included articles most closely matched the ERIC taxonomy compared to other available choices [17]. For key questions 1 and 2, we did not limit inclusion based on study design or outcome. For key question 3, we limited inclusion to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Studies were excluded for key questions if full text was not available.

Search results were uploaded into systematic review software (DistillerSR, Ottawa, Canada). In the first round of screening, abstracts and titles were evaluated for inclusion. Following abstract screening, eligibility was assessed through full-text screening. Prior to both abstract and full text screening, reviewers underwent training to ensure a basic understanding of the background of the field and purpose of the review as well as comprehension of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The initial 20 abstracts were reviewed independently and then discussed as a group. Eligibility at both levels (abstract and full-text) was assessed independently and in duplicate (L.K.J., S.T., L.R.F., and C.G.). Disagreements at the level of abstract and full text screening were resolved by consensus. If consensus could not be achieved between the two reviewers, a third reviewer arbitrated (M.R.G., T.W., or T.S.).

Data collection

The following characteristics were extracted from included studies: first author, year of publication, location, age of patient population (adult vs. child), study design, implementation strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and any of the following outcomes: statin prescribing or use, statin adherence, or LDL-C measurements.

Key question 1: what implementation strategies have been used to promote the uptake of statins?

We first summarized and described the populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes presented for all studies that reported at least one implementation strategy that could be mapped to the ERIC compilation. The ERIC compilation of nine implementation strategies categories (73 total strategies) was applied to each of the interventions to (1) count the total number of strategies and (2) describe how complete each implemented strategy was defined. One study team member, who was an author on the original ERIC compilation, ensured validity of the categories selected (T.W.) [14].

Key question 2: how completely are the implementation strategies utilized reported in studies designed to promote statin uptake?

Based on guidance from proctor and colleagues, we assessed the degree to which each strategy was completely reported including actor, action, action target, temporality, dose, implementation outcome affected, and justification (Table 2) [11].

Table 2.

Summary of the implementation strategies’ defining characteristics

| Characteristics | Definition | % (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Actor | Identify who enacts the strategy | 98% (254/258) |

| Action | Specific actions, steps, or processes that need to be enacted | 100% (258/258) |

| Action Target |

1) Specify targets according to conceptual models of implementation 2) Identify unit of analysis for measuring implementation outcomes |

95% (245/258) |

| Temporality | Specify when the strategy is used | 59% (151/258) |

| Dose | Specify dosage of implementation strategy | 52% (134/258) |

| Implementation outcome affected | Identify and measure the implementation outcome(s) that are affected by each strategy | 9% (23/258) |

| Justification | Justification for choice of implementation strategies | 6% (16/258) |

Characteristics and definitions were utilized from Proctor 2013. The justification definition was adjusted to reflect an argument for the implementation strategy by noting an implementation science framework or guidance and not an evidence-base for the intervention

Key question 3: which implementation strategy, or combination of strategies, is (are) the most effective at promoting the uptake of statins?

When present, we extracted data related to statin prescribing, statin adherence, and LDL-C reported from included RCTs. All outcomes were collected at intervention completion. Statin prescribing or use included all orders for statin medications. Statin adherence included only objective measures of adherence by either medication possession ratio (MPR) or proportion of days covered (PDC) [18]. MPR or PDC were captured as a percentage or attainment of greater than 80% adherence. LDL-C levels were recorded as LDL-C measured or achievement of an LDL-C target.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool version 2 to evaluate methodological quality of studies included in the meta-analysis for key question 3 [19]. The risk of bias in included studies was assessed in duplicate by two reviewers (L.K.J. and L.R.F.) working independently. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus; if consensus was unable to be achieved, a third reviewer arbitrated (M.R.G.).

Statistical analysis

Standardized mean differences (SMDs) with corresponding 95% CIs were estimated for continuous outcomes, and odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for binary outcomes from included studies. Publication bias was evaluated by Egger’s test [20]. Variability between included studies was assessed by heterogeneity tests using I2 statistic [21]. If overall results showed significant heterogeneity, potential sources of heterogeneity were explored by subgroup analysis. All analyses were conducted using RStudio (Version 1.0.136) using the “Meta” and “Metafor” package.

Results

Description of study selection

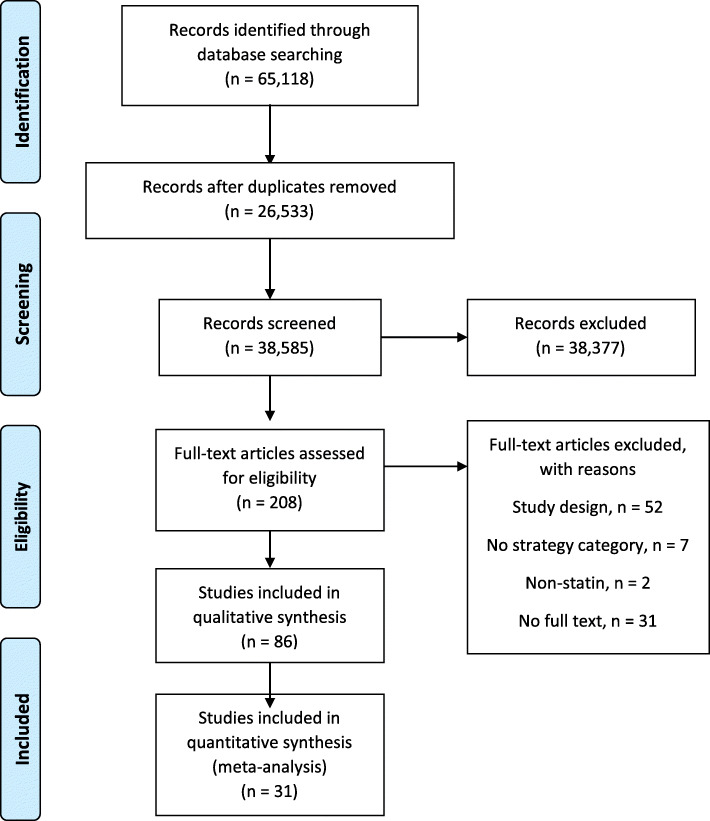

We initially identified 65,118 studies. After removing duplicates, we identified 38,585 unique citations (Fig. 1). Through abstract and title screening, 208 reports were identified for full-text review. During full-text review, 86 were selected for inclusion [12, 13, 22–105]. A complete list of excluded full-text studies with rationale for exclusion is available in Additional file 1: Appendix 2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Description of studies

Table 3 describes the included studies (more details are included in Additional file 1: Appendix 3). Almost all the implementation strategies targeted adults (two studies included pediatric patients), half were implemented in the USA, and almost all were conducted in individuals with hypercholesterolemia (two studies were conducted in individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia).

Table 3.

Study demographics

| Year | Author last name | Location | Population | Study design | Outcomes measured | Included in meta-analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Schectman [34] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | ✓ |

| 1997 | Bogden [65] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2000 | Nordmann [37] | Switzerland | Adult | RCT | Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2000 | Nguyen [38] | France | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2000 | Faulkner [71] | United States | Adult and Child | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2005 | Rachmani [36] | Israel | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2006 | Lester [41] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2006 | Lee [78] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2007 | Khanal [77] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2008 | Riesen [35] | Switzerland | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2009 | Stacy [31] | United States | Adult | RCT | Statin Adherence | ✓ |

| 2009 | Willich [89] | Germany | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2009 | McAlister [101] | Canada | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2010 | Webster [23] | Australia | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2010 | Villeneuve [103] | Canada | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2012 | Nieuwkerk [86] | Netherlands | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2013 | Zamora [12] | Spain | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2013 | Kooy [42] | Netherlands | Adult | RCT | Statin Adherence | ✓ |

| 2013 | Kardas [43] | Poland | Adult | RCT | Statin Adherence | ✓ |

| 2013 | Goswami [72] | United States | Adult | RCT | Statin Adherence | ✓ |

| 2014 | McAlister [83] | Canada | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2014 | Lowrie [100] | United Kingdom | Adult | RCT | Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2015 | Mols [54] | Denmark | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2015 | Asch [13] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2015 | Patel [82] | Australia | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2016 | Jakobsson [44] | Sweden | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 2016 | Damush [79] | United States | Adult | RCT | Statin Adherence | ✓ |

| 2018 | Choudhry [76] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | ✓ |

| 2018 | Mehrpooya [80] | Iran | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2018 | Martinez [81] | Spain | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | ✓ |

| 2018 | Osborn [104] | United Kingdom | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | ✓ |

| 1996 | Lindholm [39] | Sweden | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | |

| 2003 | Sebregts [99] | Netherlands | Adult and Child | RCT | LDL-C | |

| 2007 | Choe [95] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2008 | Hung [90] | Taiwan | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2010 | Bhattacharyya [62] | Canada | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2013 | Dresser [55] | Canada | Adult | RCT | LDL-C | |

| 2013 | Brath [60] | Austria | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2013 | Derose [85] | United States | Adult | RCT | Statin Adherence | |

| 2005 | Straka [28] | United States | Adult | Nonrandomized Clinical Trial | LDL-C | |

| 2005 | Paulos [105] | Chile | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2006 | Vrijens [24] | Belgium | Adult | RCT | Statin Adherence | |

| 2015 | Persell [102] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2017 | Bosworth [61] | United States | Adult | RCT | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2018 | Etxeberria [53] | Spain | Adult and Child | RCT | Statin Prescribing | |

| 1995 | Shaffer [94] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 1997 | Shibley [32] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 1999 | Schwed [33] | Switzerland | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2000 | Robinson [92] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2000 | Birtcher [93] | United States | Adult | Observational | Statin Prescribing | |

| 2001 | Ford [52] | United Kingdom | Adult | Observational | Statin Prescribing | |

| 2002 | Viola [25] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2002 | Geber [50] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2002 | Gavish [51] | Israel | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2002 | Hilleman [70] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C; Statin Prescribing | |

| 2003 | Truppo [27] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C; Statin Adherence | |

| 2003 | Ryan [98] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C; Statin Prescribing | |

| 2004 | Hilleman [45] | United States | Adult and Child | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2004 | de Velasco [56] | Spain | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2004 | Lappé [69] | United States | Adult | Observational | Statin Prescribing | |

| 2005 | Harats [47] | Israel | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2005 | Bassa [63] | Spain | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2005 | Brady [91] | United Kingdom | Adult | Observational | Statin Prescribing | |

| 2005 | McLeod [96] | United Kingdom | Adult | Observational | Statin Adherence | |

| 2005 | Rabinowitz [97] | Israel | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2006 | de Lusignan [57] | United Kingdom | Adult and Child | Observational | Statin Prescribing | |

| 2006 | Rehring [66] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2007 | Goldberg [48] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2008 | Stockl [29] | United States | Adult | Observational | Statin Prescribing, Statin Adherence | |

| 2008 | Hatfield [67] | United Kingdom | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2008 | Coodley [88] | United States | Both | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2009 | Stephenson [30] | United States | Adult and Child | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2009 | Lima [40] | Brazil | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2009 | Casebeer [59] | United States | Adult | Observational | Statin Adherence | |

| 2010 | Chen [75] | Taiwan | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2011 | Gitt [49] | Germany | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2011 | Chung [58] | Hong Kong | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2011 | Schmittdiel [87] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C | |

| 2012 | Aziz [68] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2012 | Farley [74] | United States | Adult | Observational | Statin Adherence | |

| 2014 | Clark [73] | United States | Adult and Child | Observational | Statin Adherence | |

| 2014 | Shoulders [84] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2015 | Vinker [26] | Israel | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing | |

| 2016 | Harrison [46] | United States | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Adherence | |

| 2017 | Andrews [64] | United States | Adult | Observational | Statin Adherence | |

| 2018 | Weng [22] | United Kingdom | Adult | Observational | LDL-C, Statin Prescribing |

Implementation strategies

All implementation strategies except “provide interactive assistance” were used (Table 4). A total of 258 uses of strategies were identified across 86 studies. On average, each study utilized three strategies (SD 2.2, range 1–13). The most utilized strategies were “train and educate the stakeholders” (studies utilized strategies in this grouping 79 times), “support clinicians” (68), and “engage consumers” (47). The most utilized individual strategies were “intervene with patients and consumers to enhance uptake and adherence” (41), and “distribute educational materials” (41) (Additional file 1: Appendix 4). Implementation strategies often did not include key defining characteristics: temporality was reported 59% of the time, dose 52%, affected outcome 9%, and justification 6% (Table 2 provides a summary and Additional file 1: Appendix 5 provides a more detailed version).

Table 4.

Summary of implementation strategies by strategy category

| Strategy category | Strategies used per category | Total count within category | Meta-analysis total count within category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use evaluative and iterative strategies | 80% (8/10) | 33 | 9 |

| Support clinicians | 80% (4/5) | 68 | 20 |

| Adapt and tailor to the context | 75% (3/4) | 4 | 2 |

| Engage consumers | 60% (3/5) | 47 | 24 |

| Train and educate the stakeholders | 55% (6/11) | 80 | 26 |

| Change infrastructure | 50% (4/8) | 9 | 2 |

| Develop stakeholder relationships | 47% (8/17) | 11 | 5 |

| Utilize financial strategies | 22% (2/9) | 6 | 2 |

| Provide interactive assistance | 0% (0/4) | 0 | 0 |

Meta-analysis

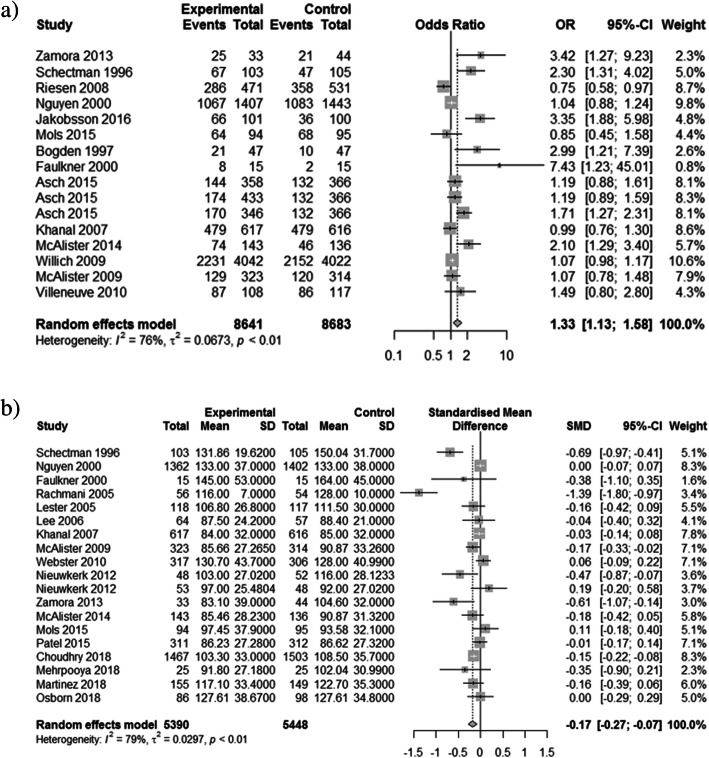

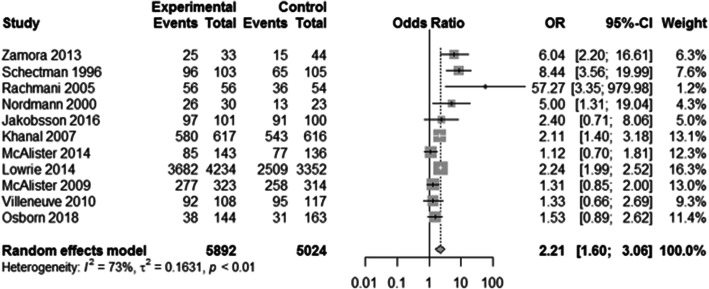

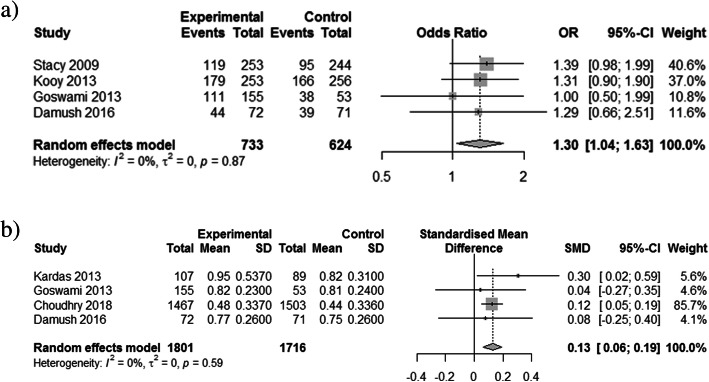

Due to the large heterogeneity between studies, effectiveness outcomes (statin prescribing, statin adherence, and LDL-C) were only extracted from RCTs. Thirty-one trials reported at least one of the three outcomes of interest. The implementation strategies examined demonstrated: significantly reduced LDL-C (LDL-C reduction: SMD − 0.17, 95% CI − 0.27 to − 0.07, p = 0.0006; met LDL-C target: OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.58, p = 0.0008) (Fig. 2), increased rates of statin prescribing (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.60 to 3.06, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3), and improved statin adherence (PDC/MPR: SMD 0.13, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.19; p = 0.0002; ≥ 80% PDC/MPR: OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.63, p = 0.023) (Fig. 4). There was inconsistency across trials based on the outcome measured; statin prescribing (I2 = 73%), statin adherence (I2 = 0%), and LDL-C (I2 = 79% (LDL-C reduction) and 76% (met LDL-C targets)). Publication bias using the Egger’s test indicated no publication bias for statin prescribing (p = 0.63), statin adherence (p = 0.83 for SMD, p = 0.22 for OR), and potential publication bias for LDL-C (p = 0.08 for SMD, p = 0.01 for OR).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of implementation strategies’ impact on LDL-C compared to control. a Achievement of target LDL-C. b Standardized mean difference in LDL-C

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of implementation strategies’ impact on statin prescribing compared to control

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of implementation strategies’ impact on statin adherence compared to control. a Medication possession ratio or portion of days covered > 80%. b Standardized mean difference in medication possession ratio or portion of days covered

Although subgroup analyses were conducted for statin prescribing and LDL-C, there were not enough studies to conduct a subgroup analysis for statin adherence (Table 5). We identified a significant difference among studies published in 2013 or later for LDL-C measured as a binary outcome (OR 1.62, 95% CI1.19–2.19, p = 0.05). We also found a significant effect on LDL-C measured as a continuous variable when more than 2 implementation strategies were utilized (SMD − 0.38 95% CI − 0.67; − 0.09, p = 0.05). There was no significant effect in the between country analysis.

Table 5.

Subgroup analyses

| Study subgroup (number of studies) | Subgroup | Comparison group | P value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio, (95% CI) | |||

| Statin prescribing (11) | |||

| More than 2 implementation strategies (6) | 2.19 (1.32–3.63) | 2.40 (1.43–4.06) | 0.80 |

| Study published in 2013 or later (5) | 1.97 (1.29–3.01) | 2.84 (1.41–5.74) | 0.36 |

| Conducted in the United States (2) | 4.00 (1.03–15.50) | 1.95 (1.33–2.84) | 0.32 |

| LDL-C (14) | |||

| More than 2 implementation strategies (4) | 1.53 (1.23–1.90) | 1.20 (0.97–1.48) | 0.12 |

| Study published 2013 or later (5) | 1.62 (1.19–2.19) | 1.13 (0.95–1.35) | 0.05 |

| Conducted in the United States (5) | 1.48 (1.12–1.95) | 1.29 (1.03–1.61) | 0.35 |

| Standardized mean difference, (95% CI) | |||

| LDL-C (17) | |||

| More than 2 implementation strategies (6) | − 0.38 (− 0.67; − 0.09) | − 0.07 (− 0.15; − 0.01) | 0.05 |

| Study published in 2013 or later (8) | − 0.12 (− 0.21; v0.02) | − 0.23 (− 0.39; − 0.07) | 0.24 |

| Conducted in the United States (6) | − 0.20 (− 0.36; − 0.04) | − 0.17 (− 0.31; − 0.03) | 0.79 |

Statin adherence was excluded because there were not enough studies to make a comparison

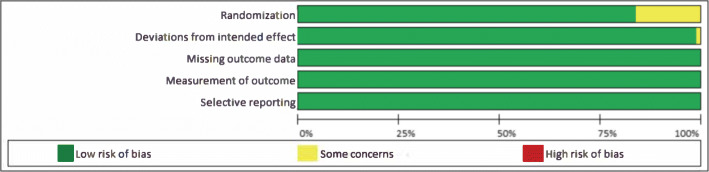

Most studies were found to be at a low risk of bias (Fig. 5 and Additional file 1: Appendix 6); therefore, we did not conduct subgroup analyses based on the risk of bias.

Fig. 5.

Risk of bias of RCTs included in the meta-analyses

Discussion

Our findings

In this review of implementation strategies regarding uptake of statins in hypercholesterolemia, we found that 38 different strategies were utilized to lower LDL-C, improve statin prescribing, and promote adherence. However, strategy components were not well defined and there was not a single strategy or group of strategies that demonstrated superior impact compared to others. Consistent with management of other diseases and conditions and literature from implementation science [106], we found evidence to support the use of multiple concurrent strategies; the use of three or more implementation strategies was associated with a greater reduction in LDL-C. We also found that studies published after 2012 had, on average, greater reductions in LDL-C through the use of the reported implementation strategies. While it cannot be definitely attributed, this could result from a better understanding of which strategies work best or could reflect a switch toward the utilization of high dose statin therapy. There was no difference in outcomes based on country where the study was conducted.

An important limitation of the many strategies described was incomplete definitions, limiting generalizability to other settings. Often, we were able to discern the actor, action, and action target but were unable to determine temporality, dose, implementation outcome affected, or justification. Without clear reporting of these factors, we are unable to interpret when these strategies should be used (temporality), how often (dosage), how the success of a specific strategy is measured (implementation outcomes affected), or when to justify the choice of a particular strategy (justification) to influence clinical practice. While the interventions appeared to be effective at increasing the utilization of statins and reducing LDL-C overall, the variable nature of the interventions studied and outcomes examined, the effectiveness of any specific strategy or set of strategies was unclear.

In addition, one category of strategies, “provide interactive assistance,” was not utilized in any of the studies included in the analysis. Among the strategies that were used, many were used in combination, but specific combinations were not used frequently enough to permit reliable subgroup analysis.

Comparison with other studies

In the field of implementation science, there has recently been a desire to improve specification of implementation strategies utilized in practice and to develop standard language and definitions for reporting these implementation strategies [11, 14, 107]. This trend has led to the development of two implementation strategy taxonomies: the ERIC compilation [14], used in this study, and the Effective Practise and Organization of Care (EPOC) taxonomy [17]. Use of these taxonomies has allowed for consistent language in reporting implementation strategies and development of tailored compilations of strategies specific to certain disease states [108, 109]. Other systematic reviews of implementation strategies in other fields (i.e., intensive care setting and oral health) have found improved outcomes when multiple implementation strategies are used but have not been able to identify the groups of strategies most likely to produce the most favorable outcomes [110–112].

An investigation of enablers and barriers to treatment adherence in familial hypercholesterolemia found seven enablers for patients that could be used to develop new interventions and matched to implementation strategies we identified in our study [113]. These enablers were “other family members following treatment regime,” “commencement of treatment from a young age,” “parental responsibility to care for children,” “confidence in ability to successfully self-manage their condition,” “receiving formal diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia,” “practical resources and support for following lifestyle treatment,” and a “positive relationship with healthcare professionals” [113]. By linking the two most frequently used strategies identified in our systematic review “intervene with patients and consumers to enhance uptake and adherence” and “distribute educational materials,” with the enablers identified above, effective implementations strategies for statin utilization can be designed.

The sustainability of interventions to promote the uptake of guidelines when intervening at the clinician level has been limited in a variety of settings [114–116]. Specifically, in cardiovascular disease, a systematic review of interventions to improve uptake of heart failure medications saw an increase in guideline uptake but not improvement in clinical outcomes [117]. Similar findings have been found in hypertension [118]. However, the success of these interventions have been limited.

Limitations and strengths

Our review is the first to comprehensively map the strategies used to increase utilization of statins among persons with hypercholesterolemia to the ERIC compilation. We chose to use ERIC due to a perceived better fit over alternatives (i.e. EPOC); however, we identified 7 studies (out of 208 identified) which could not be mapped to ERIC, exclusion of which could lead to missing important strategies. Other strengths include utilization of a medical librarian to conduct the search, searching of multiple databases which covered parts of the gray literature, and utilizing trained reviewers. Finally, we limited our search to studies in English with full-texts available. Thus, we may have missed studies not published in English or published in the gray literature (e.g., only conference abstract available in published literature) and be at risk for language bias [119] or publication bias [120]. While the Egger’s test suggested possible publication bias, we think that the risk of this is low due to our comprehensive search strategy. Further, while language bias is a possibility [119], few studies were excluded based on language so any potential impact is likely to be small.

Suggestions for future research

Consistent strategies for reporting LDL-C would significantly improve the ability to assess efficacy of an intervention. Some studies used arbitrary cut-offs for LDL-C, some used absolute values, and others used thresholds published in cholesterol guidelines [121]. This led to difficulty in aggregating data across studies. Future studies should report absolute values of LDL-C to facilitate meta-analyses directed at change of LDL-C with intervention. Generating a core outcome set for trials in hypercholesterolemia would facilitate meta-analyses and ensure all relevant outcomes are consistently measured [122]. Ideally, these studies should be registered and included in a meta-analysis in a prospective manner [123].

Clarity in the terminology, definition, and description of implementation strategies by researchers would help translation and replication of efforts. Completely reporting implementation strategies facilitates interpretation of results as well as facilitating reproducibility and scalability [11]. The field of implementation science offers guidance on how to name and report these strategies [11]. Even though this study was unable to identify a single or gold standard approach to improving statin therapy for hypercholesterolemia disorders, it provides examples of many different approaches that have some impact on outcomes relevant to care. In this way, this study provides a roadmap for future implementation to better define implementation strategies and to rigorously define and test the outcomes associated with those strategies. More guidance will be needed on the impact of strategies in different healthcare settings, because different strategies may work better in different healthcare settings so these idiosyncrasies need to be understood.

Conclusion

Implementation strategies to improve the uptake of statins among patients with hypercholesterolemia exist but they are poorly reported and generalizability is limited. While these strategies lowered LDL-C and improved adherence, significant heterogeneity made assessment of the comparative effectiveness of strategies difficult. Future studies for increasing the utilization of statins among patients with hypercholesterolemia should more clearly define strategies used, prospectively test comparative effectiveness of different strategies, and use standardized efficacy endpoints.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1. Statin uptake search strategy. Appendix 2. Excluded full text articles and rationale. Appendix 3. Detailed study demographics. Appendix 4. Count of implementation strategy organized by category and strategy. Appendix 5. Detailed Proctor’s framework description of each strategy. Appendix 6. Risk of bias

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- ERIC

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change

- LDL-C

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ORs

Odds ratios

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- SMDs

Standardized mean differences

- RCTs

Randomized clinical trails

Authors’ contributions

LKJ designed the systematic review, reviewed abstracts and full-text, extracted and analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript file. ST and CG reviewed abstracts and full-text for inclusion and extracted data and reviewed manuscript file. LHY completed search and reviewed final manuscript file. YH performed statistical analyses and risk of bias and reviewed final manuscript. ACS, AKR, AG, RCB, and SSG reviewed data and reviewed final manuscript. TLS and TJW reviewed implementation strategies categorization and final manuscript. MSW and MRG designed systematic review, reviewed data, and prepared and reviewed final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K12HL137942.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Registered in PROSPERO.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;139(25):e1082–e1143. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhabue E, Rittner SS, Carroll JE, et al. Implications of American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) cholesterol guidelines on statin underutilization for prevention of cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus among several US networks of community health centers. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(7):e005627. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Garrido E, Wei HG, Freeman A, Spettell C, Garcia-Alonso F, Lizano I, Arnold RJG, Rajda J, Steinberg G, Fuster V. Assessing the impact of medication adherence on long-term cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(8):789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin-Ruiz E, Olry-de-Labry-Lima A, Ocaña-Riola R, Epstein D. Systematic review of the effect of adherence to statin treatment on critical cardiovascular events and mortality in primary prevention. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(3):200–215. doi: 10.1177/1074248417745357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vera MA, Bhole V, Burns LC, Lacaille D. Impact of statin adherence on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(4):684–698. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez F, Maron DJ, Knowles JW, Virani SS, Lin S, Heidenreich PA. Association of statin adherence with mortality in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):206–213. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones LK, Sturm AC, Seaton TL, Gregor C, Gidding SS, Williams MS, Rahm AK. Barriers, facilitators, and solutions to familial hypercholesterolemia treatment. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner RM, Safford MM, Monda KL, Taylor B, O’Beirne R, Morris M, Colantonio LD, Dent R, Muntner P, Rosenson RS. Primary care physician perspectives on barriers to statin treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31(3):303–309. doi: 10.1007/s10557-017-6738-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ju A, Hanson CS, Banks E, Korda R, Craig JC, Usherwood T, MacDonald P, Tong A. Patient beliefs and attitudes to taking statins: systematic review of qualitative studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(671):e408–e419. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X696365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lansberg P, Lee A, Lee Z-V, Subramaniam K, Setia S. Nonadherence to statins: individualized intervention strategies outside the pill box. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2018;14:91–102. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S158641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zamora A, Fernández De Bobadilla F, Carrion C, et al. Pilot study to validate a computer-based clinical decision support system for dyslipidemia treatment (HTE-DLP) Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(2):401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asch DA, Troxel AB, Stewart WF, Sequist TD, Jones JB, Hirsch AMG, Hoffer K, Zhu J, Wang W, Hodlofski A, Frasch AB, Weiner MG, Finnerty DD, Rosenthal MB, Gangemi K, Volpp KG. Effect of financial incentives to physicians, patients, or both on lipid levels: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1926–1935. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JAE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, Proctor EK, Kirchner JAE. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). 2015; epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

- 18.Nau DP. Proportion of days covered (PDC) as a preferred method of measuring medication adherence. Pharmacy Quality Alliance; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weng S, Kai J, Tranter J, Leonardi-Bee J, Qureshi N. Improving identification and management of familial hypercholesterolaemia in primary care: Pre- and post-intervention study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;274:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster R, Li SC, Sullivan DR, Jayne K, Su SY, Neal B. Effects of internet-based tailored advice on the use of cholesterol-lowering interventions: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(3):e42. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vrijens B, Belmans A, Matthys K, de Klerk E, Lesaffre E. Effect of intervention through a pharmaceutical care program on patient adherence with prescribed once-daily atorvastatin. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(2):115–121. doi: 10.1002/pds.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viola RA, Abbott KC, Welch PG, McMillan RJ, Sheikh AM, Yuan CM. A multidisciplinary program for achieving lipid goals in chronic hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2002;3:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinker S, Bitterman H, Comaneshter D, Cohen AD. Physicians’ behavior following changes in LDL cholesterol target goals. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2015;4(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13584-015-0016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Truppo C, Keller VA, Reusch MT, Pandya B, Bendich D. The effect of a comprehensive, mail-based motivational program for patients receiving lipid-lowering therapy. Manag Care Interface. 2003;16(3):35–40+62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straka RJ, Taheri R, Cooper SL, Smith JC. Achieving cholesterol target in a managed care organization (ACTION) trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(3):360–371. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.3.360.61601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stockl KM, Tjioe D, Gong S, Stroup J, Harada ASM, Lew HC. Effect of an intervention to increase statin use in medicare members who qualified for a medication therapy management program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(6):532–540. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.6.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephenson SH, Larrinaga-Shum S, Hopkins PN. Benefits of the MEDPED treatment support program for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2009;3(2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stacy JN, Schwartz SM, Ershoff D, Shreve MS. Incorporating tailored interactive patient solutions using interactive voice response technology to improve statin adherence: results of a randomized clinical trial in a managed care setting. Popul Health Manage. 2009;12(5):241–254. doi: 10.1089/pop.2008.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibley MCH, Pugh CB. Implementation of pharmaceutical care services for patients with hyperlipidemias by independent community pharmacy practitioners. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31(6):713–719. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwed A, Fallab CL, Burnier M, Waeber B, Kappenberger L, Burnand B, Darioli R. Electronic monitoring of compliance to lipid-lowering therapy in clinical practice. J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39(4):402–409. doi: 10.1177/00912709922007976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schectman G, Wolff N, Byrd JC, Hiatt JG, Hartz A. Physician extenders for cost-effective management of hypercholesterolemia. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(5):277–286. doi: 10.1007/BF02598268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riesen WF, Noll G, Dariolu R. Impact of enhanced compliance initiatives on the efficacy of rosuvastatin in reducing low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138(29-30):420–426. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rachmani R, Slavacheski I, Berla M, Frommer-Shapira R, Ravid M. Treatment of high-risk patients with diabetes: motivation and teaching intervention: a randomized, prospective 8-year follow-up study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(3 SUPPL. 1):S22–S26. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004110965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nordmann A, Blattmann L, Gallino A, Khetari R, Martina B, Müller P, Plebani G, Schmid H, Battegay E. Systematic, immediate in-hospital initiation of lipid-lowering drugs during acute coronary events improves lipid control. Eur J Internal Med. 2000;11(6):309–316. doi: 10.1016/S0953-6205(00)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen G, Cruickshank J, Mouillard A, Dumuis ML, Picard C, Cailleteau X, Pantou X, Dupuis R, Portal JJ, Maigret P. Comparison of achievement of treatment targets as perceived by physicians and as calculated after implementation of clinical guidelines for the management of hypercholesterolemia in a randomized, clinical trial. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2000;61(9):597–608. doi: 10.1016/S0011-393X(00)88012-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindholm LH, Ekbom T, Dash C. Changes in cardiovascular risk factors by combined pharmacological and nonpharmacological strategies: the main results of the CELL study. J Intern Med. 1996;240(1):13–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.492831000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lima EMO, Gualandro DM, Yu PC, Giuliano ICB, Marques AC, Calderaro D, Caramelli B. Cardiovascular prevention in HIV patients: results from a successful intervention program. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(1):229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lester WT, Grant RW, Barnett GO, Chueh HC. Randomized controlled trial of an informatics-based intervention to increase statin prescription for secondary prevention of coronary disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kooy MJ, Van Wijk BLG, Heerdink ER, De Boer A, Bouvy ML. Does the use of an electronic reminder device with or without counseling improve adherence to lipid-lowering treatment? The results of a randomized controlled trial. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:69. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kardas P. An education-behavioural intervention improves adherence to statins. Cent Eur J Med. 2013;8(5):580–585. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakobsson S, Huber D, Björklund F, Mooe T. Implementation of a new guideline in cardiovascular secondary preventive care: subanalysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hilleman DE, Faulkner MA, Monaghan MS. Cost of a pharmacist-directed intervention to increase treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(8):1077–1083. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.11.1077.36145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrison TN, Green KR, Liu ILA, Vansomphone SS, Handler J, Scott RD, Cheetham TC, Reynolds K. Automated outreach for cardiovascular-related medication refill reminders. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18(7):641–646. doi: 10.1111/jch.12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harats D, Leibovitz E, Maislos M, Wolfovitz E, Chajek-Shaul T, Leitersdorf E, Gavish D, Gerber Y, Goldbourt U, HOLEM Study Group Cardiovascular risk assessment and treatment to target low density lipoprotein levels in hospitalized ischemic heart disease patients: results of the HOLEM study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7(6):355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldberg KC, Melnyk SD, Simel DL. Overcoming inertia: improvement in achieving target low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(9):530–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gitt AK, Jünger C, Jannowitz C, Karmann B, Senges J, Bestehorn K. Adherence of hospital-based cardiologists to lipid guidelines in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events (2L registry) Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(4):277–287. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geber J, Parra D, Beckey NP, Korman L. Optimizing drug therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease: the impact of pharmacist-managed pharmacotherapy clinics in a primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(6 I):738–747. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.9.738.34061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gavish D, Leibovitz E, Elly I, Shargorodsky M, Zimlichman R. Follow-up in a lipid clinic improves the management of risk factors in cardiovascular disease patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4(9):694–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ford DR, Walker J, Game FL, Bartlett WA, Jones AF. Effect of computerized coronary heart disease risk assessment on the use of lipid-lowering therapy in general practice patients. Coron Health Care. 2001;5(1):4–8. doi: 10.1054/chec.2000.0103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Etxeberria A, Alcorta I, Pérez I, Emparanza JI, Ruiz de Velasco E, Iglesias MT, Rotaeche R. Results from the CLUES study: a cluster randomized trial for the evaluation of cardiovascular guideline implementation in primary care in Spain. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2863-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mols RE, Jensen JM, Sand NP, et al. Visualization of coronary artery calcification: influence on risk modification. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):1023.e1023–1023.e1031. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dresser GK, Nelson SAE, Mahon JL, Zou G, Vandervoort MK, Wong CJ, Feagan BG, Feldman RD. Simplified therapeutic intervention to control hypertension and hypercholesterolemia: a cluster randomized controlled trial (STITCH2) J Hypertens. 2013;31(8):1702–1713. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283619d6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Velasco JA, Cosín J, de Oya M, de Teresa E. Intervention program to improve secondary prevention of Myocardial infarction. Results of the PRESENTE (Early Secondary Prevention) study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2004;57(2):146–154. doi: 10.1016/S0300-8932(04)77077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Lusignan S, Belsey J, Hague N, Dhoul N, Van Vlymen J. Audit-based education to reduce suboptimal management of cholesterol in primary care: a before and after study. J Public Health. 2006;28(4):361–369. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chung JST, Lee KKC, Tomlinson B, Lee VWY. Clinical and economic impact of clinical pharmacy service on hyperlipidemic management in Hong Kong. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16(1):43–52. doi: 10.1177/1074248410380207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Casebeer L, Huber C, Bennett N, et al. Improving the physician-patient cardiovascular risk dialogue to improve statin adherence. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:48. 10.1186/1471-2296-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Brath H, Morak J, Kästenbauer T, Modre-Osprian R, Strohner-Kästenbauer H, Schwarz M, Kort W, Schreier G. Mobile health (mHealth) based medication adherence measurement—a pilot trial using electronic blisters in diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(S1):47–55. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bosworth HB, Brown JN, Danus S, Sanders LL, McCant F, Zullig LL, Olsen MK. Evaluation of a packaging approach to improve cholesterol medication adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(9):e280–e286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhattacharyya O, Harris S, Zwarenstein M, Barnsley J. Controlled trial of an intervention to improve cholesterol management in diabetes patients in remote Aboriginal communities. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010;69(4):333–343. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v69i4.17629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bassa A, Del Val M, Cobos A, et al. Impact of a clinical decision support system on the management of patients with hypercholesterolemia in the primary healthcare setting. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2005;13(1):65–72. doi: 10.2165/00115677-200513010-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andrews SB, Marcy TR, Osborn B, Planas LG. The impact of an appointment-based medication synchronization programme on chronic medication adherence in an adult community pharmacy population. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(4):461–466. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bogden PE, Koontz LM, Williamson P, Abbott RD. The physician and pharmacist team: An effective approach to cholesterol reduction. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(3):158–164. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-5023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rehring TF, Stolcpart RS, Sandhoff BG, Merenich JA, Hollis HW., Jr Effect of a clinical pharmacy service on lipid control in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(6):1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hatfield J, Gulati S, Abdul Rahman MNA, Coughlin PA, Chetter IC. Nurse-led risk assessment/management clinics reduce predicted cardiac morbidity and mortality in claudicants. J Vasc Nurs. 2008;26(4):118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aziz EF, Javed F, Pulimi S, Pratap B, de Benedetti Zunino ME, Tormey D, Hong MK, Herzog E. Implementing a pathway for the management of acute coronary syndrome leads to improved compliance with guidelines and a decrease in angina symptoms. J Healthc Qual. 2012;34(4):5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lappé JM, Muhlestein JB, Lappé DL, et al. Improvements in 1-year cardiovascular clinical outcomes associated with a hospital-based discharge medication program. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(6):446–453+I-443. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hilleman D, Monaghan M, Ashby C, Mashni J, Wooley K, Amato C. Simple physician-prompting intervention drastically improves outcomes in CHD. Formulary. 2002;37:209–210. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Faulkner MA, Wadibia EC, Lucas BD, Hilleman DE. Impact of pharmacy counseling on compliance and effectiveness of combination lipid-lowering therapy in patients undergoing coronary artery revascularization: a randomized, controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(4):410–416. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.5.410.35048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goswami NJ, DeKoven M, Kuznik A, et al. Impact of an integrated intervention program on atorvastatin adherence: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:647–655. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S47518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clark B, DuChane J, Hou J, Rubinstein E, McMurray J, Duncan I. Evaluation of increased adherence and cost savings of an employer value-based benefits program targeting generic antihyperlipidemic and antidiabetic medications. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(2):141–150. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Farley JF, Wansink D, Lindquist JH, Parker JC, Maciejewski ML. Medication adherence changes following value-based insurance design. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(5):265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen C, Chen K, Hsu CY, Chiu WT, Li YC. A guideline-based decision support for pharmacological treatment can improve the quality of hyperlipidemia management. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2010;97(3):280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Choudhry NK, Isaac T, Lauffenburger JC, et al. Effect of a remotely delivered tailored multicomponent approach to enhance medication taking for patients with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes the STIC2IT cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1190–1198. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khanal S, Obeidat O, Hudson MP, et al. Active lipid management in coronary artery disease (ALMICAD) study. Am J Med. 2007;120(8):734.e711–734.e717. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296(21):2563–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Damush TM, Myers L, Anderson JA, Yu Z, Ofner S, Nicholas G, Kimmel B, Schmid AA, Kent T, Williams LS. The effect of a locally adapted, secondary stroke risk factor self-management program on medication adherence among veterans with stroke/TIA.[Erratum appears in Transl Behav Med. 2016 Sep;6(3):469; PMID: 27528534] Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(3):457–468. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0348-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mehrpooya M, Larki-Harchegani A, Ahmadimoghaddam D, et al. Evaluation of the effect of education provided by pharmacists on hyperlipidemic patient’s adherence to medications and blood level of lipids. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2018;8(1):029–033. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Párraga-Martínez I, Escobar-Rabadán F, Rabanales-Sotos J, Lago-Deibe F, Téllez-Lapeira JM, Villena-Ferrer A, Blasco-Valle M, Ferreras-Amez JM, Morena-Rayo S, del Campo-del Campo JM, Ayuso-Raya MC, Pérez-Pascual JJ. Efficacy of a combined strategy to improve low-density lipoprotein cholesterol control among patients with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized clinical trial. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patel A, Cass A, Peiris D, Usherwood T, Brown A, Jan S, Neal B, Hillis GS, Rafter N, Tonkin A, Webster R, Billot L, Bompoint S, Burch C, Burke H, Hayman N, Molanus B, Reid CM, Shiel L, Togni S, Rodgers A, for the Kanyini Guidelines Adherence with the Polypill (Kanyini GAP) Collaboration A pragmatic randomized trial of a polypill-based strategy to improve use of indicated preventive treatments in people at high cardiovascular disease risk. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(7):920–930. doi: 10.1177/2047487314530382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Padwal RS, et al. Case management for blood pressure and lipid level control after minor stroke: PREVENTION randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186(8):577–584. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shoulders BR, Franks AS, Barlow PB, Williams JD, Farland MZ. Impact of pharmacists’ interventions and simvastatin dose restrictions. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(1):54–61. doi: 10.1177/1060028013511323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Derose SF, Green K, Marrett E, Tunceli K, Cheetham TC, Chiu VY, Harrison TN, Reynolds K, Vansomphone SS, Scott RD. Automated outreach to increase primary adherence to cholesterol-lowering medications. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(1):38–43. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nieuwkerk PT, Nierman MC, Vissers MN, Locadia M, Greggers-Peusch P, Knape LPM, Kastelein JJP, Sprangers MAG, de Haes HC, Stroes ESG. Intervention to improve adherence to lipid-lowering medication and lipid-levels in patients with an increased cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(5):666–672. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schmittdiel JA, Karter AJ, Dyer W, Parker M, Uratsu C, Chan J, Duru OK. The comparative effectiveness of mail order pharmacy use vs. local pharmacy use on LDL-C control in new statin users. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1396–1402. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1805-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coodley GO, Jorgensen M, Kirschenbaum J, Sparks C, Zeigler L, Albertson BD. Lowering LDL Cholesterol in adults: a prospective, community-based practice initiative. Am J Med. 2008;121(7):604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Willich SN, Englert H, Sonntag F, Völler H, Meyer-Sabellek W, Wegscheider K, Windier E, Katus H, Müller-Nordhorn J. Impact of a compliance program on cholesterol control: Results of the randomized ORBITAL study in 8108 patients treated with rosuvastatin. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2009;16(2):180–187. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283262ac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hung CS, Lin JW, Hwang JJ, Tsai RY, Li AT. Using paper chart based clinical reminders to improve guideline adherence to lipid management. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(5):861–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brady AJB, Pittard JB, Grace JF, Robinson PJ. Clinical assessment alone will not benefit patients with coronary heart disease: failure to achieve cholesterol targets in 12,045 patients - The Healthwise II study. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(3):342–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Robinson JG, Conroy C, Wickemeyer WJ. A novel telephone-based system for management of secondary prevention to a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol < or = 100 mg/dl. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(3):305–308. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Birtcher KK, Bowden C, Ballantyne CM, Huyen M. Strategies for implementing lipid-lowering therapy: pharmacy-based approach. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(3 SUPPL. 1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00936-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shaffer J, Wexler LF. Reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in an ambulatory care system: results of a multidisciplinary collaborative practice lipid clinic compared with traditional physician-based care. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(21):2330–2335. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1995.00430210080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Choe HM, Stevenson JG, Streetman DS, Heisler M, Sandiford CJ, Piette JD. Impact of patient financial incentives on participation and outcomes in a statin pill-splitting program. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(6 Part 1):298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McLeod AL, Brooks L, Taylor V, Wylie A, Currie PF, Dewhurst NG. Non-attendance at secondary prevention clinics: the effect on lipid management. Scott Med J. 2005;50(2):54–56. doi: 10.1177/003693300505000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rabinowitz I, Tamir A. The SaM (Screening and Monitoring) approach to cardiovascular risk-reduction in primary care—cyclic monitoring and individual treatment of patients at cardiovascular risk using the electronic medical record. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12(1):56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ryan MJ, Gibson J, Simmons P, Stanek E. Effectiveness of aggressive management of dyslipidemia in a collaborative-care practice model. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(12):1427–1431. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sebregts EH, Falger PR, Bär FW, Kester AD, Appels A. Cholesterol changes in coronary patients after a short behavior modification program. Int J Behav Med. 2003;10(4):315–330. doi: 10.1207/S15327558IJBM1004_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lowrie R, Lloyd SM, McConnachie A, Morrison J. A cluster randomised controlled trial of a pharmacist-led collaborative intervention to improve statin prescribing and attainment of cholesterol targets in primary care. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.McAlister FA, Fradette M, Majumdar SR, et al. The enhancing secondary prevention in coronary artery disease trial. CMAJ. 2009;181(12):897–904. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Persell SD, Shah S, Brown T, et al. Individualized risk communication and lay outreach for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in community health centers: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2015;130:A14008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Villeneuve J, Genest J, Blais L, Vanier MC, Lamarre D, Fredette M, Lussier MT, Perreault S, Hudon E, Berbiche D, Lalonde L. A cluster randomized controlled trial to evaluate an ambulatory primary care management program for patients with dyslipidemia: the TEAM study. CMAJ. 2010;182(5):447–455. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Osborn D, Burton A, Hunter R, Marston L, Atkins L, Barnes T, Blackburn R, Craig T, Gilbert H, Heinkel S, Holt R, King M, Michie S, Morris R, Morris S, Nazareth I, Omar R, Petersen I, Peveler R, Pinfold V, Walters K. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of an intervention for reducing cholesterol and cardiovascular risk for people with severe mental illness in English primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Paulós CP, Akesson Nygren CE, Celedón C, Cárcamo CA. Impact of a pharmaceutical care program in a community pharmacy on patients with dyslipidemia. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(5):939–943. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Briss PA, Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Zaza S. Developing and using the guide to community preventive services: lessons learned about evidence-based public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25(1):281–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, et al. Enhancing the Impact of Implementation Strategies in Healthcare: A Research Agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7:3. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123–157. doi: 10.1177/1077558711430690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Graham AK, Lattie EG, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Smith JD, Schueller SM, Stadnick NA, Brown CH, Mohr DC. Implementation strategies for digital mental health interventions in health care settings. Am Psychol. 2020;75(8):1080–1092. doi: 10.1037/amp0000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Trogrlić Z, van der Jagt M, Bakker J, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yi Mohammadi JJ, Franks K, Hines S. Effectiveness of professional oral health care intervention on the oral health of residents with dementia in residential aged care facilities: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(10):110–122. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mills KT, Obst KM, Shen W, Molina S, Zhang HJ, He H, Cooper LA, He J. Comparative effectiveness of implementation strategies for blood pressure control in hypertensive patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(2):110–120. doi: 10.7326/M17-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kinnear FJ, Wainwright E, Perry R, Lithander FE, Bayly G, Huntley A, Cox J, Shield JPH, Searle A. Enablers and barriers to treatment adherence in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e030290. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ament SM, de Groot JJ, Maessen JM, Dirksen CD, van der Weijden T, Kleijnen J. Sustainability of professionals' adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008073. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jordan P, Mpasa F, Ten Ham-Baloyi W, Bowers C. Implementation strategies for guidelines at ICUs: a systematic review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017;30(4):358–372. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-08-2016-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Unverzagt S, Oemler M, Braun K, Klement A. Strategies for guideline implementation in primary care focusing on patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(3):247–266. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shanbhag D, Graham ID, Harlos K, Haynes RB, Gabizon I, Connolly SJ, van Spall HGC. Effectiveness of implementation interventions in improving physician adherence to guideline recommendations in heart failure: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e017765. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Milchak JL, Carter BL, James PA, Ardery G. Measuring adherence to practice guidelines for the management of hypertension: an evaluation of the literature. Hypertension. 2004;44(5):602–608. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000144100.29945.5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, Moulton K, Clark M, Fiander M, Mierzwinski-Urban M, Clifford T, Hutton B, Rabb D. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(2):138–144. doi: 10.1017/S0266462312000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schmucker CM, Blumle A, Schell LK, et al. Systematic review finds that study data not published in full text articles have unclear impact on meta-analyses results in medical research. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0176210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bays HE, Jones PH, Brown WV, Jacobson TA, National LA. National lipid association annual summary of clinical lipidology 2015. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8(6 Suppl):S1–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(3):280. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Seidler AL, Hunter KE, Cheyne S, Ghersi D, Berlin JA, Askie L. A guide to prospective meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367:l5342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Appendix 1. Statin uptake search strategy. Appendix 2. Excluded full text articles and rationale. Appendix 3. Detailed study demographics. Appendix 4. Count of implementation strategy organized by category and strategy. Appendix 5. Detailed Proctor’s framework description of each strategy. Appendix 6. Risk of bias

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.