Abstract

Background:

Chronic nausea in pediatrics is a debilitating condition with unclear etiology. We aimed to define hemodynamic and neurohumoral characteristics of chronic nausea associated with orthostatic intolerance in order to improve identification and elucidate mechanism.

Methods:

Children (10–18 years) meeting Rome III criteria for functional dyspepsia with nausea and symptoms of orthostatic intolerance (OI) completed a Nausea Profile Questionnaire followed by prolonged (45 minutes rather than the traditional 10 minutes) head-upright tilt (HUT)(70 degree tilt up) test. Circulating catecholamines, vasopressin, aldosterone, renin, and angiotensins were measured supine and after 15 minutes into HUT. Beat-to-beat heart rate and blood pressure were continuously recorded to calculate their variability and baroreflex sensitivity.

Key Results:

Within 10 and 45 minutes of HUT, 46% and 85% of subjects, respectively, had an abnormal tilt test (orthostatic hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia, or syncope). At 15 and 45 minutes of HUT, nausea was elicited in 42% and 65% of subjects, respectively. Higher Nausea Profile Questionnaire scores correlated with positive HUT testing at 10 minutes (p=0.004) and baroreflex sensitivity at 15 minutes (p≤0.01). Plasma vasopressin rose 33-fold in subjects with HUT-induced nausea compared to 2-fold in those who did not experience HUT-induced nausea (p<0.01).

Conclusions & Inferences:

In children with chronic nausea and OI, longer duration HUT elicited higher frequency of abnormal tilt testing and orthostatic-induced nausea. The Nausea Profile Questionnaire predicted the orthostatic response to tilt testing. Exaggerated vasopressin release differentiated patients with HUT-induced nausea (vs. those without nausea), suggesting a possible mechanism for chronic nausea in childhood.

Keywords: FGIDs, functional gastrointestinal disorders, OI, orthostatic intolerance, HUT, head upright tilt, POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, OH, orthostatic hypotension, BRS, baroreflex sensitivity, HRV, heart rate variability

Abbreviated abstract:

We aimed to define hemodynamic and neurohumoral characteristics of chronic nausea associated with orthostatic intolerance. In children with chronic nausea and OI, longer duration HUT elicited higher frequency of abnormal tilt testing and orthostatic-induced nausea with the Nausea Profile Questionnaire predicting the orthostatic response to tilt testing. Exaggerated vasopressin release differentiated patients with HUT-induced nausea (vs. those without nausea).

Nausea is a common and highly debilitating symptom with a prevalence of up to 10% in otherwise healthy pediatric patients in the community 1. Nausea is very heterogeneous in its presentation, and its causes are often multifactorial with varied and numerous precipitating triggers 2, making it difficult to determine etiology and optimal treatment strategies. Oftentimes, when routine diagnostic testing fails to identify a cause for the nausea, patients are treated with empiric, costly, and not patient-specific therapy in an attempt to alleviate their symptoms, resulting in highly variable outcomes 3,4. We previously demonstrated that several children with dyspepsia (in which nausea was the predominant symptom) experienced orthostatic intolerance (OI) with dizziness when standing 5. When studied with prolonged head upright tilt (HUT) table testing, 80% met criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), orthostatic hypotension, or syncope 5,6. When OI was treated with fludrocortisone not only did symptoms of dizziness improve, but nausea and abdominal pain also substantially decreased 7. In these children nausea was also associated with anxiety 8.

In consideration of these seemingly connected clinical findings and motivated by a paucity of pediatric studies in the literature, we sought to investigate the etiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) such as chronic nausea with OI 9. Here we evaluated children and adolescents presenting with chronic nausea and OI by exploring hemodynamic, autonomic, and neurohumoral parameters during prolonged HUT, with the aim to provide insight into underlying mechanisms that could guide diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects.

Children, ages 10–18 years were recruited from a pediatric GI clinic at a tertiary care children’s hospital if they met Rome III criteria for childhood functional dyspepsia with nausea as the predominant symptom2, had reported symptoms of OI (specifically, dizziness/lightheadedness or fainting upon standing), and no identified metabolic, mechanical, or mucosal inflammatory cause for their GI symptoms. Rome III functional dyspepsia includes the following 3 diagnostic criteria occurring at least once per week for at least 2 months prior to diagnosis: 1)Persistent upper abdominal discomfort/pain; 2)Symptoms not relieved by defecation or associated with change in stool frequency/form; and 3)No evidence of an inflammatory, anatomic, metabolic, or neoplastic process that explains symptoms. We focused on functional dyspepsia with nausea because the Rome III lacks defined criteria for pediatric functional nausea. Parents and children provided written consent/assent prior to study participation in this Institutional Review Board approved study.

Nausea Assessment.

Nausea was evaluated in two ways. First, each patient completed the Nausea Profile Questionnaire (NPQ)10 within two weeks prior to HUT testing. The NP is a 17-item questionnaire to assess the subjective experience of nausea and provide a Total Score and 3 Subscale Scores (Somatic, Gastrointestinal Distress and Emotional Distress), with a range from 0–100 (higher scores are indicative of more intense nausea). The NPQ is validated for use in adults 10 and is a reliable measure in adolescents 8. Second, prior to HUT, subjects were instructed to self-report symptoms of nausea as they became evident during the course of the entire HUT.

Procedures.

Testing included HUT testing, continuous recording of beat-to-beat HR and BP, and bloodwork evaluation of neurohumoral factors.

HUT Test Protocol.

Medications that might impact HUT results were discontinued for a minimum of 48 hours prior to HUT testing. Following a 200 kcal breakfast of juice and toast, subjects fasted for two hours before beginning HUT baseline recording. Each subject wore comfortable clothing and was positioned supine on the tilt table for placement of surface electrodes in anticipation of heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) monitoring as described below. Baseline recording in the supine position for 15 minutes was followed by immediate upright tilt to 70 degrees, then the upright position was maintained for up to 45 minutes. After 45 minutes the tilt-table was returned to the horizontal position for an additional 15 minutes of post-HUT recording with the subject in the supine position. HUT testing was considered “positive” [HUT(+)] if HR and BP results met criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) (sustained HR increase by 40 beats/minute within 10 minutes of HUT), orthostatic hypotension (OH) (sustained reduction of systolic BP by 20 mmHg or diastolic BP by 10 mmHg within 3 minutes of HUT), or syncope 11. Categorization of patient diagnoses into normal versus HUT(+) was performed at multiple time points into the HUT as well (10, 15, 20, 30, and 45 minutes).

Continuous Recording of Heart Rate and Blood Pressure Variability.

HR and BP were recorded continuously from a non-invasive finger arterial pressure measurement probe during baseline, throughout the HUT, and during post-HUT testing. Mean values for HR and BP in the last 5 minutes of the baseline recording and throughout the HUT and post-HUT testing were calculated in 60 second increments, and mean values were compared to mean HR and BP values calculated in the 2 minutes preceding blood sample collection (after 15 minutes of HUT). Measurements and calculations for heart rate variability (HRV), blood pressure variability (BPV), and baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) were conducted as previously described 12,13.

Measurements of Neurohumoral Factors in Blood.

Blood was unobtrusively collected from a heparin lock (placed 30 minutes before study onset) after 15 minutes in the supine position during baseline recording then after 15 minutes of HUT (at 70 degree incline) to measure: epinephrine (Epi), norepinephrine, (NE), angiotensin II (Ang II), angiotensin 1–7 (Ang-[1–7]), aldosterone (Aldo), renin, and arginine vasopressin (AVP). Measures of Aldo, renin, and angiotensins were carried out in a CLIA-certified Biomarker Analytical Core Laboratory. Measures of catecholamines (Epi, NE, dopamine) and AVP were carried out in the hospital’s Pathology Lab as previously reported 14.

Statistical Analysis.

For continuous variables, means and standard error of the mean (SEM) were calculated. Two-way ANOVA tests were conducted to examine the effect of HUT duration on HUT(−) versus HUT(+) groups. When appropriate, t-tests and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine specific effects of HUT on hemodynamic and neurohumoral variables between and among groups. Unpaired t-tests were performed comparing subjects with and without self-reported nausea during HUT, followed by a Welch’s Correction for unequal variances. Paired t-tests were performed to compare supine measures to intra-HUT measures for neurohumoral results. Mann Whitney tests (unpaired t-tests) and Wilcoxon’s Signed Rank tests (paired t-tests) were used when data sets were not normally distributed. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA). The significance level was set at p = 0.01 to control for Type 1 error.

Results

Forty-eight patients (36 females) with median age (± SEM) 15.2 ± 0.3 years, with nausea-predominant functional dyspepsia and OI symptoms underwent 45-minute HUT testing with continuous HR and BP recording, and completed the Nausea Profile Questionnaire and neurohumoral blood testing.

HUT Results and Nausea Assessment

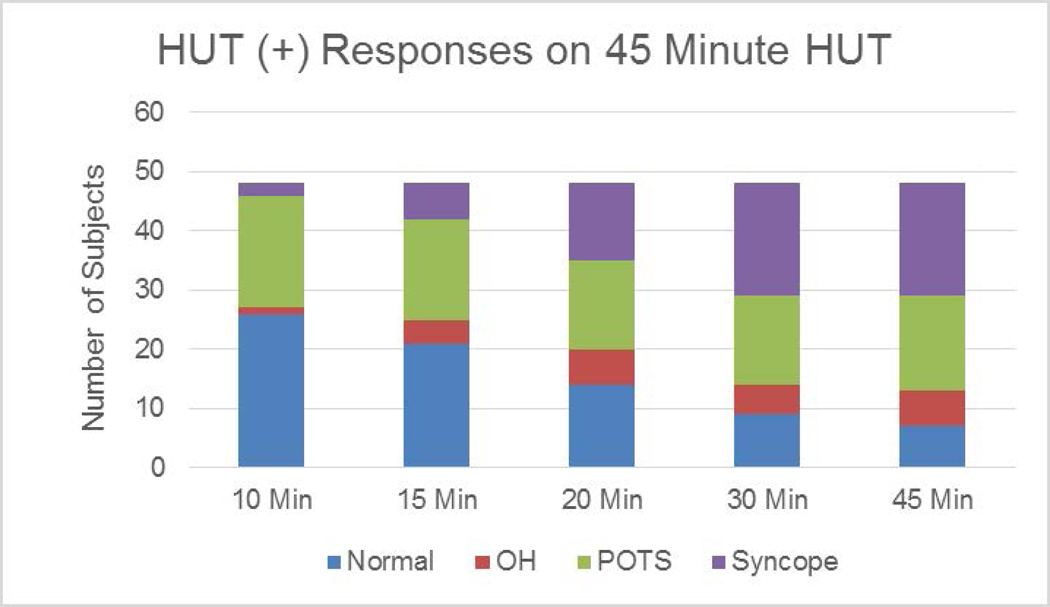

Thirty-one subjects (64.5%) reported nausea at any time during the entire 45-minute HUT test. To more accurately compare the relationship between nausea and neurohormonal levels, we stratified the cohort into those children who reported nausea during the first 15 minutes of the tilt-up position vs. those who did not. With this definition, 42% of subjects experienced HUT-associated nausea (n=20) and 58% did not (n=28). There were no significant differences in age, ratio of females:males, weight (57.7 ± 3.1 kg vs. 61.4 ± 3.1 kg), BMI (21.5 ± 1.1 vs. 23.3 ± 0.9), or duration of HUT between subjects with HUT-associated nausea on HUT and those without nausea on HUT. Of the 48 subjects, 22 (46%) were HUT(+) after the first 10 minute of HUT increasing to 85% by 45 minutes of HUT (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Incremental Diagnostic Categorization on Prolonged Duration of Orthostatic Challenge on Head up Tilt (from 10 to 45 minutes)

Nausea Profile Questionnaire and Continuous Recording of HR and BP

NPQ scores out of 100 for each category for all 48 subjects are as follows (mean ± SEM): Total Nausea: 43 ± 3; somatic distress: 45 ± 3; GI distress: 56 ± 3; emotional distress: 29 ± 3. Subjects who were HUT(+) at 10 minutes into tilt up had significantly higher total NPQ scores compared to HUT(−) subjects at 10 minutes. Subjects who were HUT(+) at 10 and 15 minutes also had significantly higher somatic and emotional distress scores, compared to HUT(−) subjects. There were no differences in GI distress sub scores between HUT(+) and HUT(−) subjects. No significant differences in NPQ scores between groups were found for time intervals beyond 15 minutes into HUT (Table 1).

Table 1A.

Total Nausea Profile Questionnaire Scores

| Time into Tilt Up Position when HUT was categorized as HUT+ | HUT(−) | HUT(+) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 35 ± 3 (n=26) | 52 ± 4 (n=22) | 0.004 |

| 15 min | 35 ± 4 (n=21) | 49 ± 3 (n=27) | NS |

| 20 min | 37 ± 5 (n=14) | 45 ± 3 (n=34) | NS |

| 30 min | 34 ± 7 (n=9) | 45 ± 3 (n=39) | NS |

| 45 min | 34 ± 9 (n=7) | 44 ± 3 (n=41) | NS |

Heart rate and blood pressure variability measures (HRV, BRS, and BPV) evaluated as a percent of baseline (supine) did not distinguish between HUT(+) and HUT(−) subjects in either the supine or tilted position. However, with HUT-induced perturbation, we identified significant associations between NPQ scores and BRS during HUT. Total NPQ and somatic NPQ scores negatively correlated with HUT measures of BRS (r = −0.33, p ≤ 0.01) and (r = −0.375, p = 0.008), respectively.

Measurements of Neurohumoral Factors in the Blood

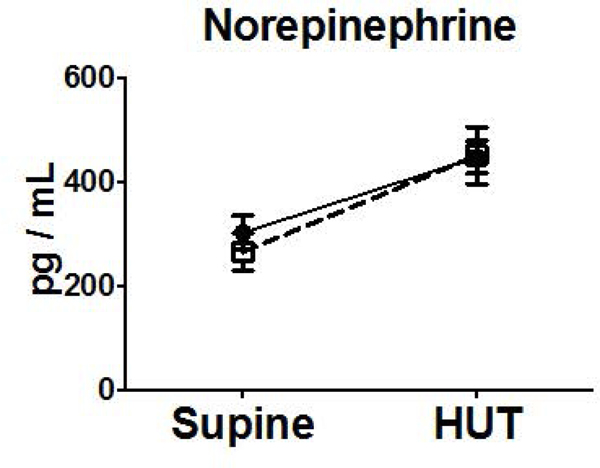

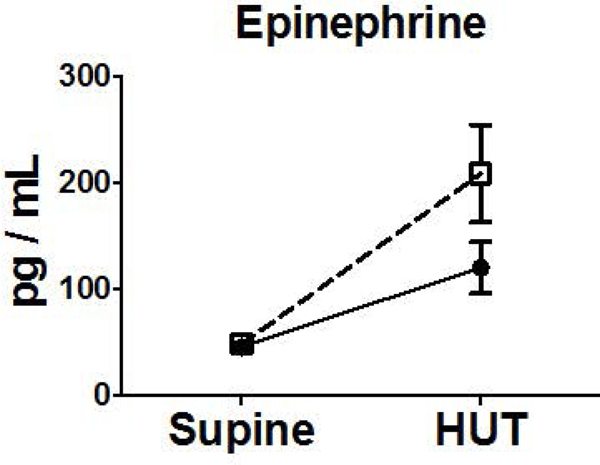

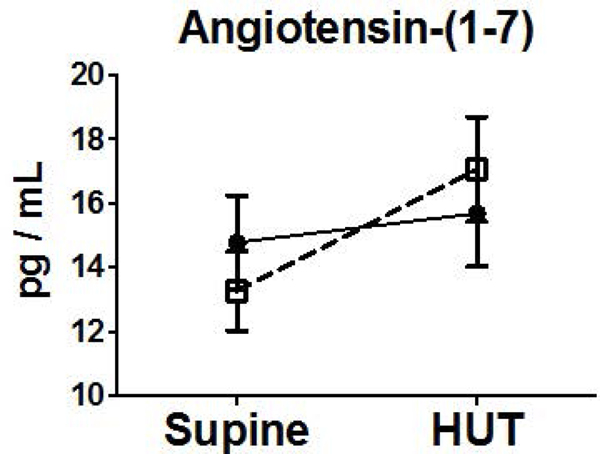

Neurohumoral measurements did not differ at baseline in subjects with nausea during HUT or those without nausea during HUT. Subjects in both groups exhibited increases in NE, Epi, Renin, Ang II, AVP from supine to HUT. There was a 33-fold increase in AVP compared to a 2-fold increase observed in those without nausea on HUT (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Orthostatic Changes in Neurohumoral Factors (NE (A), Epi (B), and AVP (C), Renin (D), Aldo (E), Ang II (F), Ang-(1–7) (G)) Comparing Blood Measures Supine to 15 Minutes into HUT for Subjects Experiencing HUT-Induced Nausea (◻) versus subjects without nausea during HUT (●). (**p<0.01) (pg, picogram; mL, milliliter)

Discussion

The objective of this study was to better characterize the clinical phenotype of pediatric chronic nausea and OI towards the goal of identifying potential mechanisms involved in producing these debilitating symptoms. To address this, we examined the relationship among the hemodynamic, nausea, and neurohumoral responses to HUT using standard protocols 11 with the exception of extending the duration of HUT to 45 minutes. Our results show that in children with functional dyspepsia and chronic nausea: 1) 46% of subjects had a positive HUT within 10 minutes of tilt increasing to 85% after 45 minutes; 2) HUT evoked symptoms of nausea in 65% of subjects independent of meeting OI criteria; 3) HUT(+) subjects had higher total NPQ scores as well as higher scores in both somatic and emotional distress subdomains, but not in the GI subdomain. Total and somatic NPQ scores correlated with impaired BRS; 4) Subjects experiencing nausea during HUT demonstrated a marked increase in AVP compared to those who did not experience nausea.

The HUT test is currently an accepted standard as an orthostatic stress test; however, the optimal duration for HUT for OI remains unclear 11,15,16. In our first attempt to study a patient population in whom nausea was the predominant symptom in addition to OI, we favored a longer length of tilt test. While our approach was different from the traditional 10 minute HUT test, we were able to identify a larger percentage of subjects with HUT-associated nausea using the prolonged HUT method. GI symptoms have been previously reported to occur later in the HUT 5,17,18, where the longer duration of HUT may unmask the GI-predominant symptoms as opposed to the ability of the shorter duration HUT test to detect OI (primarily POTS) 7,19. Future studies are needed to determine the most suitable HUT duration for patients with co-existing GI and orthostatic symptoms.

While these findings suggest an association between OI and nausea, they do not prove causality. Before attempting to explore potential mechanisms involved in the observed HUT responses, we aimed to better characterize the nausea symptoms experienced by patients towards defining their presenting phenotype. To do this, we utilized the NPQ. The questionnaire was designed to allow evaluation of characteristics of nausea categorized into 3 “dimensions” – GI, somatic, and emotional distress 10. While the NPQ instrument measures some of the typical symptoms associated with nausea (feeling sick, ill, queasy – GI subscale), it also measures symptoms often observed with OI (fatigue, feeling weak, hot, sweaty, lightheaded, and shaky – somatic subscale). It further addresses components of psychological stress (feeling nervous, scared/afraid, worried, upset, panicked, hopeless – emotional subscale). All subjects studied endorsed symptoms on the somatic subscale with all but one endorsing symptoms on the GI subscale (98%). Six subjects did not endorse items on the emotional distress subscale 12.5%, but the finding that a substantial majority of these subjects endorsed items on each of these scales supports the discriminating value of this multidimensional approach to the assessment of nausea. When HUT(+) and HUT(−) subjects were compared, HUT(+) subjects not only had higher NP total scores, but also had significantly higher somatic and emotional distress scores than those who were HUT(−). There was no difference in GI distress scores between the groups. Interestingly, the total NPQ and somatic NPQ scores were negatively correlated with measures of autonomic function taken during the HUT, specifically BRS. This is consistent with previous studies highlighting autonomic dysfunction in patients with functional dyspepsia, nausea, and abdominal distress 20–25. These findings further support the use of questionnaires that integrate both autonomic and psychological assessment in addition to GI symptoms26.

To explore potential underlying mechanisms in these subjects, we measured serum neurohormones, which have been associated with both autonomic dysregulation and GI symptoms – specifically, Epi, NE, AVP, Aldo, renin, and angiotensins 27–29. While hormonal changes associated with the autonomic nervous system have been studied in patients with chronic nausea 21–23,30, a comprehensive panel evaluating the impact of orthostatic challenge during HUT has not been employed in a pediatric population. Our methodology was unique in that the neurohumoral profile was measured in the supine position and during HUT in pediatric patients to more accurately relate real-time changes between the onset of nausea and cardiovascular symptoms and hormone levels. This differs from previous work in adults using HUT in which sample collection was taken in the supine position alone or after completion of a 30-minute test 31,32. We have previously shown that subjects with an abnormal HUT have an exaggerated neurohumoral response compared to those with a normal HUT 14. In our current study, comparing HUT-associated nausea versus absence of nausea on HUT, the one distinct and markedly significant difference occurred with AVP. Release of AVP can be stimulated through many complex physiological mechanisms 33,34. The positive relationship between AVP and nausea has been reported in adults 35,36. Higher levels of plasma AVP also have been associated with anxiety and depression symptoms 37,38. Thus, the mechanisms leading to AVP release in our subjects may be multifactorial. Our patient population exhibited a diverse spectrum of symptoms, including GI, orthostatic, and psychological (notably anxiety) 8 as evidenced by the NPQ. It was beyond the scope of the current study to examine the multiple triggers for increased AVP release including serum osmolality, changes in blood volume and BP, the stress hormone cortisol and markers of inflammation 33,39–43. However, our findings support further study of AVP with chronic nausea and OI towards determining the specific roles of GI tract, autonomic nervous system, and underlying psychological stress.

Despite the compelling results described here, our study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small and by design did not include a healthy control comparison cohort. Second, recorded physiologic measures were limited to HR and BP but inclusion of cerebral regional blood flow, splanchnic blood flow, and end tidal carbon dioxide might have provided further insight into mechanism. Third, the optimal timing of blood collection of neurohumoral measures was limited to two time points but might be more informative if measured at the same timepoints as HUT duration analysis and subject report of nausea were performed. And finally, assessing additional markers of stress or anxiety in real-time during HUT may delineate the potential role of physiological and psychological stress in these children.

In conclusion, in children and adolescents presenting with chronic nausea and OI, prolongation of upright tilt identified a greater number of subjects with a positive HUT as well as HUT-induced nausea that would have otherwise been missed. This underscores the need to better determine optimal HUT duration for patients with co-existing GI and orthostatic symptoms. Higher NPQ scores in HUT (+) patients suggests that the NPQ may serve as a discriminating tool to predict the orthostatic response to tilt testing. Higher somatic and emotional subdomain, but not GI subdomain scores, emphasizes the multi-factorial nature for these symptoms and the need to identify symptoms beyond the GI tract in children with FGIDs such as dyspepsia and chronic nausea. Finally, a marked increase in arginine vasopressin uniquely differentiated subjects with HUT-induced nausea. Taken together, these results begin to delineate the inter-relationship of orthostatic stressor duration and related physiologic measures, mechanism of neurohumoral effect (primary vs. secondary), and patient perception of symptoms as we struggle to decrease disease-burden by identifying patient-specific interventions for these vulnerable patients with chronic nausea.

Table 1B.

Nausea Profile Somatic Distress Sub Scores

| Time into Tilt Up Position when HUT was categorized as HUT+ | HUT(−) | HUT(+) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 38 ± 4 (n=26) | 54 ± 4 (n=22) | 0.01 |

| 15 min | 36 ± 4 (n=21) | 52 ± 3 (n=27) | 0.01 |

| 20 min | 38 ± 6 (n=14) | 48 ± 3 (n=34) | NS |

| 30 min | 34 ± 8 (n=9) | 48 ± 3 (n=39) | NS |

| 45 min | 33 ± 9 (n=7) | 47 ± 3 (n=41) | NS |

Table 1C.

Nausea Profile GI Distress Sub Scores

| Time into Tilt Up Position when HUT was categorized as HUT+ | HUT(−) | HUT(+) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 50 ± 4 (n=26) | 63 ± 5 (n=22) | NS |

| 15 min | 53 ± 5 (n=21) | 58 ± 5 (n=27) | NS |

| 20 min | 55 ± 6 (n=14) | 56 ± 4 (n=34) | NS |

| 30 min | 51 ± 8 (n=9) | 57 ± 4 (n=39) | NS |

| 45 min | 52 ± 10 (n=7) | 56 ± 3 (n=41) | NS |

Table 1D.

Nausea Profile Emotional Distress Sub Scores

| Time into Tilt Up Position when HUT was categorized as HUT+ | HUT(−) | HUT(+) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 20 ± 3 (n=26) | 40 ± 5 (n=22) | 0.004 |

| 15 min | 18 ± 4 (n=21) | 37 ± 4 (n=27) | 0.004 |

| 20 min | 22 ± 5 (n=14) | 32 ± 4 (n=34) | NS |

| 30 min | 21 ± 7 (n=9) | 31 ± 3 (n=39) | NS |

| 45 min | 20 ± 8 (n=7) | 31 ± 3 (n=41) | NS |

Key Points.

Chronic nausea is prevalent and heterogeneous in pediatrics. We investigated chronic nausea with orthostatic intolerance.

Prolonged tilt test evoked nausea in most subjects. Nausea Profile Questionnaire scores correlated with positive tilt tests. Subjects with tilt-induced nausea demonstrated increases in vasopressin compared to those without nausea.

Longer duration tilt test may identify children with orthostatic-induced nausea. The Nausea Profile Questionnaire may predict orthostatic response to tilt testing. Exaggerated vasopressin release will differentiate patients with orthostatic-induced nausea versus those without orthostatic-induced nausea.

Acknowledgments, Funding, and Disclosures

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the American Heart Association National Center Clinical Research Program Grant (AHA12CRP94200029, PI - John Fortunato). Additional support from the Farley Hudson Foundation (Jacksonville, NC) and the Hypertension and Vascular Research Center of Wake Forest School of Medicine is gratefully acknowledged. ALW was supported by the Studies in Translational Regenerative Medicine training program (T32EB014836) at Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the WFU Graduate School.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: No competing interests declared.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01617616

References

- 1.Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, Rzepski B, Andrulonis PA. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. The Journal of pediatrics. 1996;129(2):220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman D, Corazziari E, Delvaux M. Rome III: Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovacic K, Miranda A, Chelimsky G, Williams S, Simpson P, Li B. Chronic idiopathic nausea of childhood. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014;164(5):1104–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhroove G, Chogle A, Saps M. A million-dollar work-up for abdominal pain: is it worth it? Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2010;51(5):579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortunato J, Shaltout H, Larkin M, Rowe P, Diz D, Koch K. Fludrocortisone improves nausea in children with orthostatic intolerance (OI). Clinical autonomic research : official journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society. 2011;21(6):419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaltout H, Wagoner A, Diz D, Fortunato J. Impaired hemodynamic response to head up tilt in adolescents presenting chronic nausea and orthostatic intolerance. Hypertension. 2014;64:A513. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortunato J, Wagoner A, Harbinson R, D’Agostino R Jr., Shaltout H, Diz D. Effect of fludrocortisone acetate on chronic unexplained nausea and abdominal pain in children with orthostatic intolerance. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2014;59(1):39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarbell S, Shaltout H, Wagoner A, Diz D, Fortunato J. Relationship among nausea, anxiety, and orthostatic symptoms in pediatric patients with chronic unexplained nausea. Experimental brain research. 2014;232(8):2645–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacic K, Williams S, Li BUK, Chelimsky G, Miranda A. A high prevalence of nausea in children with pain-associated functional gastrointestinal disorders. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2013;57(3):311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muth E, Stern R, Thayer J, Koch K. Assessment of the multiple domains of nausea: The Nausea Profile (NP). Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1996;40(5):511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod F, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. . Clinical autonomic research : official journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society. 2011;21:69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemper K, Shaltout H. Non-verbal communication of compassion: measuring psychophysiologic effects. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaltout H, Tooze J, Rosenberger E, Kemper K. Time, touch, and compassion: Effects on autonomic nervous system and well-being. Explor J Sci Heal. 2012;8:177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagoner AL, Shaltout HA, Fortunato JE, Diz DI. Distinct neurohumoral biomarker profiles in children with hemodynamically defined orthostatic intolerance may predict treatment options. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2016;310(3):H416–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plash WB, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, et al. Diagnosing postural tachycardia syndrome: comparison of tilt testing compared with standing haemodynamics. Clinical science. 2013;124(2):109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart JM, Boris JR, Chelimsky G, et al. Pediatric Disorders of Orthostatic Intolerance. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeiro A, Saad C, Zanella T, Mulinari R, Kohlman O. Vasopressin maintains blood pressure in diabetic orthostatic hypotension. Hypertension. 1988;11(suppl I):I–217 - I-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagoner A, Shaltout H, D’Agostino E, Diz D, Fortunato J. Relationship of arginine vasopressin and blood pressure in patients with orthostatic intolerance. Hypertension. 2013;62:A261. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chelimsky G, Chelimsky TC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of pediatric autonomic disorders. Seminars in pediatric neurology. 2013;20(1):27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farmer A, Al Omran Y, Aziz Q, Andrews P. The role of the parasympathetic nervous system in visually induced motion sickness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. . Experimental brain research. 2014;232:2665–2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farmer A, Ban V, Coen S, et al. Visually induced nausea causes characteristic changes in cerebral, autonomic and endocrine function in humans Journal of Physiology. 2015;593:1183–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motion Muth E. and space sickness: Intestinal and autonomic correlates. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2006;129:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muth E, Koch K, Stern R. Significance of autonomic nervous system activity in functional dyspepsia. Digest Dis Sci. 2000;45:854–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ojha A, Chelimsky T, Chelimsky G. Comorbidities in pediatric patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011;158(1):20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan S, Hanauer J, Rowe P, Barron D, Darbari A, Oliva-Hemker M. Gastrointestinal symptoms associated with orthostatic intolerance. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2005;40(4):425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sletten D, Suarez G, Low P, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS-31: A refined and abbreviated composite autonomic symptom score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1196–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim M, Chey W, Owyang C, Hasler W. Role of plasma vasopressin as a mediator of nausea and gastric slow wave dysrhythmias in motion sickness American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272(4 Pt 1):G853–G862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch K. A noxious trio: nausea, gastric dysrhythmias and vasopressin. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1997;9(3):141–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern R, Koch K, Andrew P. Nausea: Mechanisms and Management. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Napadow V, Sheehan J, Kim J, et al. The brain circuitry underlying the temporal evolution of nausea in humans. Cerebral Cortex. 2013;23:806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garland E, Raj S, Black B, Harris P, Robertson D. The hemodynamic and neurohumoral phenotype of postural tachycardia syndrome. Neurology. 2007;69:790–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart J, Glover J, Medow M. Increased plasma angiotensin II in postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is related to reduced blood flow and blood volume Clin Sci 2006;110:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koshimizu T, Nakamura K, Egashira N, Hiroyama M, Nonoguchi H, Tanoue A. Vasopressin V1a and V1b Receptors: From Molecules to Physiological Systems. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1813–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mavani G, DeVita M, Michelis M. A Review of the nonpressor and nonantidiuretic actions of the hormone vasopressin Front Med. 2015;2:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch K. Gastric dysrhythmias: a potential objective measure of nausea. Experimental brain research. 2014;232(8):2553–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu L, Koch K, Summy-Long J, al. e. Hypothalamic and gastric myoelectrical responses during vection-induced nausea in healthy Chinese subjects. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 1993;265(4 Pt 1):E578–E584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goekoop JG, de Winter RP, de Rijk R, Zwinderman KH, Frankhuijzen-Sierevogel A, Wiegant VM. Depression with above-normal plasma vasopressin: validation by relations with family history of depression and mixed anxiety and retardation. Psychiatry research. 2006;141(2):201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caldwell HK, Lee HJ, Macbeth AH, Young WS 3rd. Vasopressin: behavioral roles of an “original” neuropeptide. Progress in neurobiology. 2008;84(1):1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker C, Richards L, Dayan C, Jessop D. Corticotropin-releasing hormone immunoreactivity in human T and B cells and macrophages: colocalization with arginine vasopressin. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15(11):1070–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chikanza I, Grossman A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-mediated immunomodulation: arginine vasopressin is a neuroendocrine immune mediator. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(2):131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Möhring J, Glänzer K, Maciel JJ, et al. Greatly enhanced pressor response to antidiuretic hormone in patients with impaired cardiovascular reflexes due to idiopathic orthostatic hypotension J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1980;2(4):367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cowley A, Monos E, Guyton A. Interaction of vasopressin and the baroreceptor reflex system in the regulation of arterial blood pressure in the dog. Circ Res 1974;34(4):505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liard J. Vasopressin in cardiovascular control: role of circulating vasopressin. Clin Sci 1984;67(5):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]