Abstract

Objective:

Psychosocial interventions are historically underutilized by cancer caregivers, but support programs delivered flexibly over the Internet address multiple barriers to care. We adapted Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for cancer caregivers, an in-person psychotherapeutic intervention intended to augment caregivers’ sense of meaning and purpose and ameliorate burden, for delivery in a self-administered web-based program, the Care for the Cancer Caregiver (CCC) Workshop. The present study evaluated the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of this program.

Methods:

Eighty-four caregivers were randomized to the CCC Workshop or waitlist control arm. Quantitative assessments of meaning, burden, anxiety, depression, benefit finding, and spiritual well-being were conducted preintervention (T1), within 2-weeks postintervention (T2), and 2- to 3-month follow-up (T3). In-depth semistructured interviews were conducted with a subset of participants.

Results:

Forty-two caregivers were randomized to the CCC Workshop. Attrition was moderate at T2 and T3, with caregiver burden and bereavement as key causes of drop-out. At T2 and T3, some observed mean change scores and effect sizes were consistent with hypothesized trends (eg, meaning in caregiving, benefit finding, and depressive symptomatology), though no pre-post significant differences emerged between groups. However, a longitudinal mixed-effects model found significant differential increases in benefit finding in favor of the CCC arm.

Conclusions:

The CCC Workshop was feasible and acceptable. Based on effect sizes reported here, a larger study will likely establish the efficacy of the CCC Workshop, which has the potential to address unmet needs of caregivers who underutilize in-person supportive care services.

Keywords: cancer caregivers, Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy, psychosocial oncology, supportive care

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Comprehensive care for patients with cancer involves attending to the psychosocial needs of their informal caregivers (ICs),1 among whom burden is well documented.2 A critical, potential driving, element of burden is existential distress, which includes feelings of hopelessness, demoralization, loss of personal meaning and dignity, burden towards others, and the desire for death or the decreased will to live.3 Existential distress is common among ICs and may lead to increased feelings of guilt and powerlessness. The competing demands of caregiving, other caregiving responsibilities (ie, childcare), paid employment, and personal life goals have the potential to lead to psychological, spiritual, and existential distress.4,5 Despite this, the caregiving experience is also an opportunity for meaning-making and growth,6 and finding meaning in caregiving has the potential to buffer against burden. Indeed, a growing number of studies have documented the experience of posttraumatic growth7 as a result of stressful experiences, and finding meaning has been proposed as one mechanism through which positive outcomes can be achieved.8

A limited number of psychotherapeutic interventions address existential distress or meaning-making among ICs,9 despite recognition that attention to existential distress is a critical component of palliative care. Our group developed Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP),10,11 a therapeutic model intended to ameliorate existential and spiritual distress. Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy has demonstrated efficacy in improving spiritual well-being and a sense of meaning, and decreasing symptoms of anxiety in patients with advanced cancer, and has been adapted for ICs (Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for cancer caregivers [MCP-C]12). The goal of MCP-C is to help ICs connect to sources of meaning to promote resilience during and after caregiving and buffer against burden and poor bereavement outcomes. In its original format, MCP-C is delivered in in-person group (8, 1.5-h-long sessions) and individual (7, 1-h-long sessions) sessions. Similar to delivery of MCP to patients with advanced cancer,13 attrition from MCP-C groups has been approximately 30% by session 4 of 8. Indeed, ICs report many barriers to psychosocial service use, including limited time to travel to and from treatment centers, financial constraints, and guilt. As such, in-person supportive services are generally underutilized by ICs,14 and telehealth is increasingly relied upon for the delivery of support.15,16

We adapted MCP-C for delivery over the Internet to attend to the documented barriers to engaging ICs in in-person support.17 The resultant intervention—the Care for the Cancer Caregiver Workshop (CCC Workshop)—consisted of a series of 5 self-administered webcasts, each of which included didactic components, video clips of therapeutic interactions of MCP-C therapists and (trained actors portraying) ICs demonstrating the MCP-C principles, and a message board where participants posted responses to the experiential exercise questions that form the backbone of MCP-C. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy (via measures of meaning making, caregiver burden, depression and anxiety, spiritual well-being, and benefit finding) of the CCC Workshop among ICs across the United States through a pilot randomized controlled trial.

2 |. METHOD

2.1 |. Participants

Adults who via self-report identified as ICs (age ≥ 18) of patients with any site or stage of cancer were recruited from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and across the United States through the American Cancer Society. Research staff utilized a variety of recruitment strategies. Advertisements for the study were posted on various online social networks including Facebook, Twitter, The American Cancer Society Website, and LinkedIn. Additionally, paper copies of the advertisements were distributed in MSK clinics and Hope Lodges across the United States. These recruitment strategies proved most effective, providing 84% of the participant sample. The remaining 16% of participants were referred by family or friends (4%) or were unable to provide a referral source (12%). The advertisements prompted interested ICs to call a phone number specifically used for recruitment for this study. Research staff explained the study and completed the screening process. Informed consent was obtained either in person (written) or over the phone (verbal). Verbal consents were imperative to the success of this study as it enabled ICs across the country to quickly enroll. Overall, of the 84 participants randomized, 29 were recruited from a variety of websites (eg, Facebook and Twitter), 31 directly from the American Cancer Society, and 17 from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The referral source for 7 participants was not recorded. Informal caregivers with significant psychiatric or cognitive disturbance sufficient to preclude providing informed consent and those unable to access or use a computer with Internet were excluded.

2.2 |. Measures

2.2.1 |. Demographic form

Demographic information including gender, age, race, ethnicity, education, employment, religious affiliation, and marital status was collected at baseline. Information regarding whether the patient and IC cohabitate, patient-IC relationship type (ie, spouse and parent), length of caregiving (ie, years caregiving and hours per week spent providing care), and caregiver reported patient-related information (ie, site and stage of disease) was also collected.

2.2.2 |. Meaning in caregiving

The Finding Meaning through Caregiving Scale18 is a 43-item self-report measure that assesses ways ICs find meaning through caregiving and yields an overall and 3 subscale (loss/powerlessness, provisional meaning, and ultimate meaning) scores, with higher scores indicating greater meaning in caregiving. The measure has been validated with both African American and Caucasian ICs of persons with dementia.18

2.2.3 |. Meaning and purpose in life

Sense of meaning and purpose in life was assessed by using the well-validated Life Attitude Profile-Revised (LAP-R19), a 48-item self-report measure of discovered meaning and purpose in life, as well as the motivation to find meaning and purpose in life, based on Frankl’s work. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale of agreement evaluating 6 dimensions (purpose, coherence, life control, death acceptance, existential vacuum, and goal seeking) used to calculate 2 composite subscales: the Personal Meaning Index (having life goals and a sense of direction) and Existential Transcendence (degree to which meaning and purpose has been discovered), with higher scores indicating higher levels of meaning and purpose. The LAP-R has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.77–0.91).

2.2.4 |. Caregiver burden

The Caregiver Reaction Assessment is a 24-item self-report measure that assesses multiple dimensions of burden, including esteem, impact on family support, finances, schedule, and health. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher burden. The Caregiver Reaction Assessment has been used widely in studies with cancer ICs20 and has demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity.20

2.2.5 |. Depression and anxiety

Depression and anxiety were assessed by using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,21 a 14-item questionnaire with separate (7-item) depression and anxiety subscales with higher scores indicating worsening depression and anxiety. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale has been well tested as a measure of overall psychological distress in cancer populations and has demonstrated strong test-retest reliability and validity.22

2.2.6 |. Spiritual well-being scale

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Spiritual Well-Being Scale23 is a brief self-report measure designed to assess the nature and extent of individuals’ spiritual well-being.24 The FACIT generates 2 subscales (faith, or the importance of faith/spirituality, and meaning /peace) and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.25 Higher scores indicate higher levels of spiritual well-being.

2.2.7 |. The Benefit-Finding Scale

The Benefit Finding Scale is a 17-item measure of perceived benefits adapted from Behr’s Positive Contributions Scale26 for a breast cancer population.27 It has been modified to assess potential benefits from caregiving, including personal priorities, acceptance, daily activities, family, world views, relationships, and purpose. The Benefit Finding Scale has demonstrated reliability and validity, and internal consistency is consistently high across studies, ranging from 0.91 to 0.95.27 Higher scores indicate greater benefit finding.

2.2.8 |. Workshop completion questionnaire

This semistructured interview evaluated participants’ impressions regarding (1) access (ie, experience using the workshop website, webcasts, and discussion boards), (2) appearance of the workshop website and webcasts, (3) presentation and delivery of the webcasts, and (4) the extent to which participants were impacted by the webcasts. The measure combined a series of 64 items rated on Likert scales and open-ended questions that allowed participants to provide detailed feedback regarding their experience and explanations of answers to the Likert-type questions.

2.2.9 |. Postworkshop interview

A semistructured interview guide was developed to more thoroughly evaluate participants’ reactions to the CCC Workshop, including overall impressions of each webcast, the extent to which they had an understanding of MCP principles after viewing each webcast, and feedback regarding their use of the message board and overall usability of the workshop.

2.3 |. Intervention

2.3.1 |. CCC Workshop

The CCC Workshop included 5 webcasts. The Introductory Webcast was based upon Sessions 1 and 2 of MCP-C and provided an overview of MCP modules (ie, legacy, choice, creativity, and connectedness) and a discussion about identity in the context of caregiving. Each of the 4 subsequent webcasts was devoted to one of the 4 sources of meaning that are the focus of MCP-C and included (1) education about the source of meaning and (2) experiential exercises that asked participants to write responses to food-for-thought questions based on the MCP-C manual. After viewing each webcast, participants were prompted to join the discussion board linked to that particular webcast, where they could post responses to the experiential exercise questions and interact with other participants. Both the webcasts and the discussion board were password-protected and available to participants and the study team. Importantly, the CCC Workshop was completely self-administered; once participants were enrolled and received access, study staff was not involved in the delivery of the webcasts. As such, the CCC Workshop afforded participants great flexibility in time and pacing of engagement.

2.3.2 |. Waitlist control arm

Participants were offered what is considered “usual care” at the American Cancer Society: the provision of the American Cancer Society’s Telephone helpline number (1-800-227-2345) and direction to the American Cancer Society website (www.cancer.org) where participants could find local and national resources. Upon completion of all assessments, waitlist-control arm participants were offered the opportunity to complete the CCC Workshop without any additional assessments.

2.4 |. Procedures

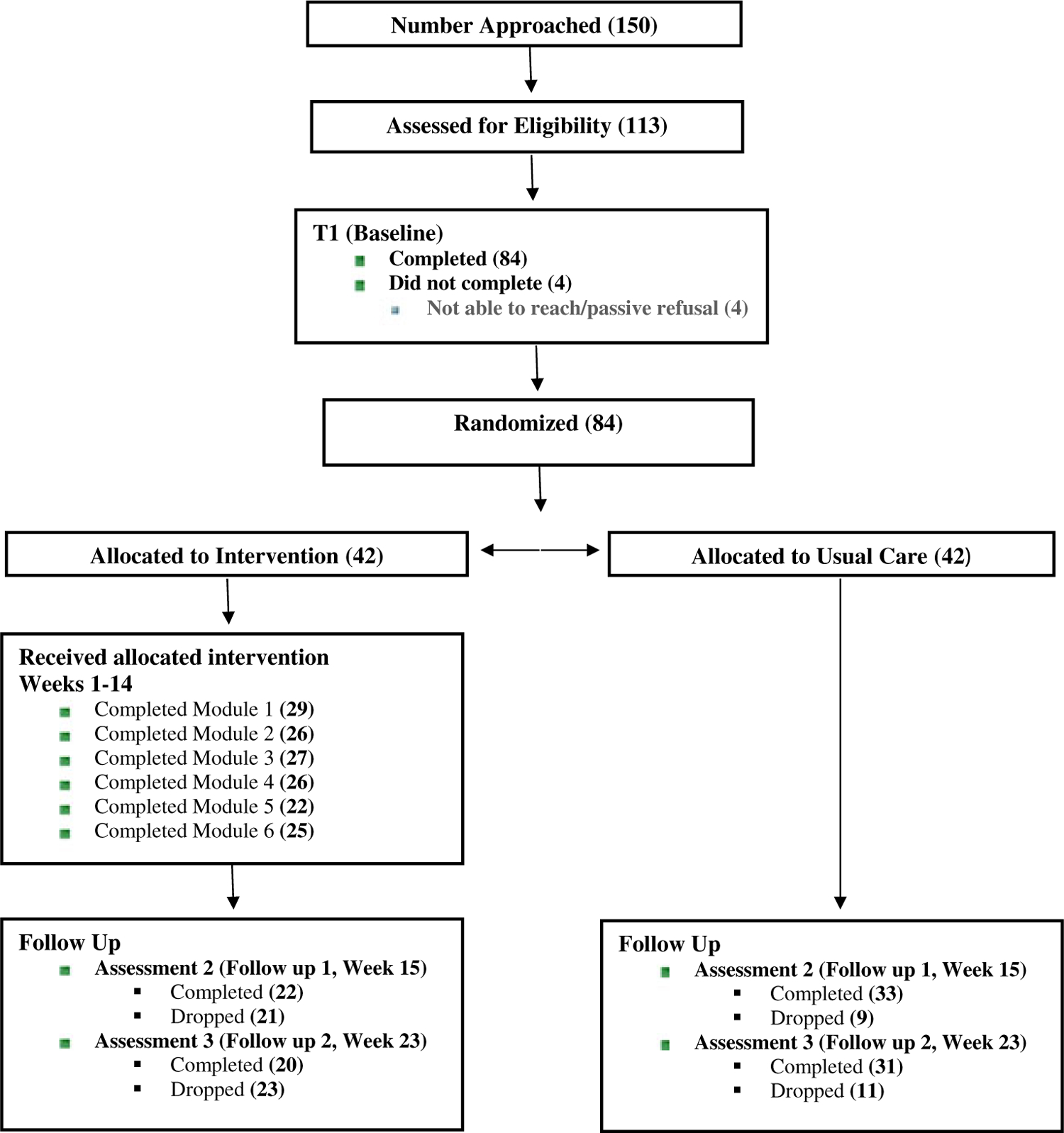

Following informed consent, all participants completed a battery of measures online (T1) assessing meaning and purpose, caregiver burden, depression and anxiety, social support, benefit finding, and spiritual well-being. Upon completion of T1, participants were randomized to the CCC Workshop or the waitlist control arm. All CCC Workshop participants received access to a secure webpage maintained by CancerConnect, which is overseen by OMNI Health Media, a leading specialty website developer and publisher of consumer health information. Care for the Cancer Caregiver Workshop participants were asked to complete the workshop within 14 weeks of T1. An assessment matching the one administered at baseline (excluding demographic information) was administered at the completion of participants’ last webcast (T2) and 2 to 3 months after completion of the workshop (T3). These follow-up assessments were completed online. Participants randomized to the waitlist control arm were assessed after consent (T1), 2 months (± 4 weeks) after the initial assessment (T2), and 2 to 3 months after the second assessment (T3). Upon completion of T3, both the CCC Workshop participants and the waitlist control group received an American Cancer Society book for cancer caregivers, “Cancer Caregiving A to Z.” Participants assigned to the CCC Workshop were also invited to complete an optional in-depth, semistructured interview over the telephone about their experience, including topics they found most beneficial and ways the workshop could be improved to better meet their needs. See Figure 1 for study consort diagram.

FIGURE 1.

Consort diagram

As a means of addressing potential attrition, study staff called or emailed (depending on participant preference) active participants once every 2 weeks to remind them to complete webcasts or follow-up assessments and to manage any concerns raised by participants. Research staff offered to complete assessments or navigate the webcasts in real time with participants if they were encountering any technological issues.

Study procedures were reviewed by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Institutional Review Board (approval number 14–208), and all participants provided informed consent before enrollment.

2.5 |. Analytic approach

Descriptive statistics of all measures were calculated, and baseline comparisons of the 2 intervention arms were assessed using chi-square for categorical demographic characteristics and independent sample t-test for numeric demographics and all psychosocial measures. Two change scores were calculated for each measure, for each individual, as the increase or decrease in the measure from baseline to postintervention and from baseline toT3. Within group, Cohen’s d standardized effect sizes were calculated for each time point. To test for differential changes in measures between the 2 arms, an independent sample t-test was then conducted on the change scores for each measure, and each follow-up. To control for confounding effects of baseline characteristics, and to aggregate findings for both follow-up time points, a mixed-effects model was then fitted for each measure, where the measure was regressed on a random, per-person intercept, and fixed effects for arm, indicator that the measure was posttreatment, an interaction between arm and posttreatment, and any important covariates as identified above. Each participant contributed up to 3 records for each model, and baseline effects were accounted for via the random intercept. A significant finding on the interaction term would indicate that the CCC arm displayed differential increase in the measure from preassessment to postassessment. Statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.2.1 software package.

Audio recordings of the semistructured interviews were transcribed and analyzed by using thematic text analysis.28–30 First, an analysis team of study investigators read each transcript, highlighted important content, and recorded reflections (ie, margin coding).30 Second, team members completed a written analysis template with exemplary quotations for each transcript. This process was repeated for all interviews, and the team met throughout the process to reach consensus regarding key observations. Third, the team met to identify thematic similarities and differences noted between individual interviews, and generated higher-order interpretive themes that best captured the major findings across all interviews.

3 |. RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, of the 84 participants randomized, most were middle-aged, female, and relatively well educated and affluent. Most ICs lived with care recipients, who had primarily advanced disease. The CCC arm had significantly more female (P = .01) and White (P = .03) participants than the waitlist arm. Importantly, a greater proportion of patients of ICs randomized to the CCC arm (69%) were identified as having Stage IV cancer than in the control arm, (45%; χ2 [1, N = 84] = 4.94, P < .05). Attrition was high but comparable to other studies enrolling ICs: 28 participants dropped before T2, and an additional 5 before T3. Attrition at T2 was higher in the CCC arm (P < .01) and among male participants (P < .01). Additionally, participants lost to follow-up were on average providing care for 1.2 years less than those who completed the study, though this difference was nonsignificant (P = .34). Although the outcome measures are all validated, we assessed internal validity of each measure within our sample and found good or excellent consistency (α≥ 0.8) on all measures except caregiver burden, which had only acceptable consistency at α = 0.77. No baseline scores varied significantly by intervention arm, nor did those who dropped out vary significantly on baseline measures or demographic characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Group | CCC | Waitlist | All | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Currently providing care | Constantly since diagnosis | 36 | 86 | 32 | 76 | 68 | 81 | .28 |

| On and off since diagnosis | 6 | 14 | 8 | 19 | 14 | 17 | ||

| Stopped, began again | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Type of Cancer | Breast | 1 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 7 | 8 | .22 |

| Colon/rectum/prostate/ test | 6 | 14 | 9 | 21 | 15 | 18 | ||

| Blood | 5 | 12 | 7 | 17 | 12 | 14 | ||

| Panc/Stom/kidney/Bladd | 7 | 17 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 12 | ||

| Lung or bronchus | 6 | 14 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 12 | ||

| Other | 17 | 40 | 13 | 31 | 30 | 36 | ||

| Educational attainment | High school diploma/GED | 3 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 6 | .36 |

| Voc. school or some college | 12 | 29 | 6 | 14 | 18 | 21 | ||

| College degree | 14 | 33 | 14 | 33 | 28 | 33 | ||

| Graduate school | 13 | 31 | 19 | 45 | 32 | 38 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Employment | Full-time employment | 20 | 48 | 17 | 40 | 37 | 44 | .18 |

| Part-time employment | 8 | 19 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 13 | ||

| Self-employed | 2 | 5 | 6 | 14 | 8 | 10 | ||

| Retired | 2 | 5 | 6 | 14 | 8 | 10 | ||

| Unemployed | 10 | 24 | 9 | 21 | 19 | 23 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 2 | 5 | 10 | 24 | 12 | 14 | .01 |

| Female | 40 | 95 | 32 | 76 | 72 | 86 | ||

| Annual household income | Less than $20 000 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 7 | .05 | ||

| $20 000 to $39 999 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 17 | 10 | 12 | ||

| $40 000 to $74 999 | 9 | 21 | 7 | 17 | 16 | 19 | ||

| $75 000 or more | 20 | 48 | 24 | 57 | 44 | 52 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 4 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Marital status | Single, never married | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 7 | .94 |

| Married or cohabitating | 34 | 81 | 35 | 83 | 69 | 82 | ||

| Divorced or separated | 5 | 12 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 11 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | African American/Black | 1 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 6 | .03 |

| Caucasian/White | 39 | 93 | 33 | 79 | 72 | 86 | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Other | 5 | 12 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Relationship to cancer patient | Parent | 7 | 17 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 13 | .78 |

| Spouse/partner | 25 | 60 | 26 | 62 | 51 | 61 | ||

| Child | 6 | 14 | 7 | 17 | 13 | 15 | ||

| Sibling | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Other | 2 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Religion | Catholic | 8 | 19 | 16 | 38 | 24 | 29 | .30 |

| Jewish | 7 | 17 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 12 | ||

| Protestant | 9 | 21 | 9 | 21 | 18 | 21 | ||

| None | 4 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Other | 14 | 33 | 10 | 24 | 24 | 29 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Live with the cancer patient | Yes-all the time | 28 | 67 | 29 | 69 | 57 | 68 | .76 |

| Yes-since initial diagnosis | 5 | 12 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 11 | ||

| No | 9 | 21 | 8 | 19 | 17 | 20 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Cancer staging | Stage I | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 7 | .18 |

| Stage II | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Stage III | 3 | 7 | 8 | 19 | 11 | 13 | ||

| Stage IV | 29 | 69 | 19 | 45 | 48 | 57 | ||

| Other | 6 | 14 | 9 | 21 | 15 | 18 | ||

| Age | Mean (SD) | 48.3 (11.4) | 51.9 (11.2) | 50.1 (11.3) | .15 | |||

| Daily hours providing care | Mean (SD) | 9.8 (8.4) | 8.4 (7.7) | 9.1 (8.1) | .39 | |||

| Baseline Measures | ||||||||

| FMTCS: Meaning in caregiving | 137.2 (19.8) | 140.6 (22.1) | 138.9 (20.9) | .40 | ||||

| LAP-R: Personal meaning | 48.4 (15.0) | 49.8 (15.3) | 49.1 (15.1) | .45 | ||||

| LAP-R: Existential transcend | 45.7 (29.8) | 46.6 (33.4) | 46.1 (31.5) | .68 | ||||

| BFS: Benefit finding | 40.5 (14.8) | 42.4 (14.6) | 41.5 (14.7) | .89 | ||||

| CRA: Caregiver burden | 82.2 (11.2) | 80.2 (10.8) | 81.2 (11.0) | .56 | ||||

| HADS: Depression | 7.4 (3.1) | 7.0 (3.4) | 7.2 (3.2) | .52 | ||||

| HADS: Anxiety | 12.5 (2.2) | 11.8 (2.2) | 12.1 (2.2) | .21 | ||||

| SWB: Meaning/peace | 18.9 (5.1) | 20.0 (6.1) | 19.4 (5.6) | .36 | ||||

| SWB: Faith | 9.1 (4.7) | 8.6 (4.6) | 8.9 (4.6) | .62 | ||||

Note: P-values for difference between arms are based on chi-squared distribution for nominal categories, except in the cases of income, staging, age, hours providing care, and baseline measures; P-values for income and staging are based on Mantel-Haenszel chi-square, and P-values for age, hours of care, and baseline measures are independent sample t-tests. “Other” cancers include brain, oral, skin, uterine, and other.

In changes in outcome variables for each of the 2 time points, some observed mean change scores and effect sizes were consistent with hypothesized trends, though no significant differences emerged between groups. Meaning in caregiving increased for the CCC arm by a mean of 3.41 between baseline and T2, compared to a mean increase of 1.12 in the waitlist arm. This change was even more dramatic over the baseline to T3 time period, where the CCC arm increased by a mean of 10.9, compared to a mean increase of 2.58 in the waitlist arm. The effect sizes for those change scores were 0.21 and 0.61 for the CCC arm at T2 and T3, respectively, versus only 0.04 and 0.09 for the waitlist arm. For the Existential Transcendence subscale of the LAP-R, the CCC group had nearly no change at T2 (mean decrease = 0.06), compared to the waitlist group who averaged a decrease of 2.45. For benefit finding, the CCC group had a mean increase of 2.77 at T2, while the waitlist arm had a decrease of 1.55, corresponding to effect sizes of 0.20 for CCC and −0.16 for the waitlist group. This effect was magnified at T3, where the CCC group exhibited a mean increase of 5.25 and the waitlist group a mean decrease of 0.32, corresponding to effect sizes of 0.41 and −0.10, respectively. Depression decreased at T1 by a mean of 0.55 for the CCC group, compared to no change (mean = 0.00) in the waitlist group. At T2, the standardized effect size for the change in the CCC arm was −0.38, compared to −0.17 for the waitlist arm. Change scores by follow-up time point, for each measure and arm, are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of change scores by arm

| Measure | Baseline toT2 | Baseline toT3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | P-value | N | Mean (SD) | P-value | |

| FMTCS: Meaning in caregiving | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | 3.41 (14.1) | 0.56 | 20 | 10.9 (16.8) | 0.08 |

| Waitlist | 33 | 1.12 (14.4) | 31 | 2.58 (16.2) | ||

| All | 55 | 2.04 (14.2) | 51 | −0.05 (10.5) | ||

| LAP-R: Personal meaning | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | 0.97 (7.7) | 0.86 | 21 | 0.27 (9.2) | 0.86 |

| Waitlist | 34 | 1.42 (10.3) | 32 | −0.27 (11.4) | ||

| All | 56 | 1.24 (9.3) | 53 | −0.84 (2.7) | ||

| LAP-R: Existential transcend | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | −0.06 (16.9) | 0.68 | 21 | −2.35 (22.4) | 0.81 |

| Waitlist | 34 | −2.45 (23.3) | 32 | −4.07 (26.7) | ||

| All | 56 | −1.51 (20.8) | 53 | −1.22 (3.0) | ||

| BFS: Benefit finding | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | 2.77 (9.1) | 0.15 | 20 | 5.25 (10.1) | 0.06 |

| Waitlist | 33 | −1.55 (11.8) | 31 | −0.32 (10) | ||

| All | 55 | 0.18 (10.9) | 51 | −3.39 (24.9) | ||

| CRA: Caregiver burden | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | 0.77 (5.7) | 0.66 | 20 | −3.80 (7.0) | 0.15 |

| Waitlist | 34 | −0.03 (7.2) | 31 | −0.81 (7.2) | ||

| All | 56 | 0.29 (6.6) | 51 | 1.86 (10.3) | ||

| HADS: Depression | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | −0.64 (2.1) | 0.64 | 20 | −1.75 (3.7) | 0.51 |

| Waitlist | 33 | −0.30 (2.8) | 31 | −1.03 (3.8) | ||

| All | 55 | −0.44 (2.5) | 51 | −1.31 (3.8) | ||

| HADS: Anxiety | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | −0.77 (2.3) | 0.93 | 20 | −1.80 (2.9) | 0.66 |

| Waitlist | 33 | −0.70 (3.3) | 31 | −1.32 (4.2) | ||

| All | 55 | −0.73 (2.9) | 51 | −1.51 (3.7) | ||

| SWB: Meaning/peace | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | −0.14 (5.1) | 0.86 | 20 | 2.05 (5.8) | 0.23 |

| Waitlist | 33 | 0.09 (4.4) | 31 | 0.29 (4.5) | ||

| All | 55 | 0.00 (4.7) | 51 | 0.24 (3.4) | ||

| SWB: Faith | ||||||

| CCC | 22 | −0.09 (3.6) | 0.83 | 20 | 0.55 (3.9) | 0.61 |

| Waitlist | 33 | 0.12 (3.4) | 31 | 0.03 (3.1) | ||

| All | 55 | 0.04 (3.5) | 51 | 0.98 (5.1) | ||

Note. P-values are based on independent sample t-test of the change scores.

A mixed-effects model, incorporating random per-person intercept, was fitted to regress each measure on treatment arm, indicator of posttreatment, interaction of arm and posttreatment, and adjusting for gender and indicators for higher annual household income ($75 000 or higher) and White/Caucasian race. The model for benefit finding found significantly differential increase in score by the CCC (b for interaction = 5.01, P = .03). No other outcome measures had significant differential posttreatment effects by treatment arm.

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 12 CCC participants within 1 month of T3. Participants were asked to provide feedback on the content and accessibility of the webcasts and discussion boards.

Key themes and illustrative examples that emerged are presented in Table 3. Participants were enthusiastic about receiving support online that focused on their unique needs. They found the length of each webcast appropriate, though indicated interest in additional video clips of therapeutic interactions. Furthermore, participants appreciated that the Introductory Webcast included a definition of the word Meaning as it applies to caregiving, and a synopsis of what to expect in the upcoming webcasts. Participants indicated an increased understanding of key MCP terms, specifically Choice and Legacy, and found that the discussion of Creativity highlighted the importance of continuing to take responsibility for their lives and engaging in self-care despite their care responsibilities. Importantly, participants were readily able to access the discussion boards despite varying degrees of self-reported technological ability.

TABLE 3.

Key themes from semistructured interviews

| Themes | Illustrative Caregiver Responses |

|---|---|

| Legacy | “This webcast made me think about how where people come from influences the choices they make.” “Legacy to me is looking at what I’ve done, and what I’ve gotten most from this caregiving role. I hope others will see that and understand that even though it’s a hard time, there are a lot of positives you can take from it.” |

| Choice | “This webcast reminded me that I can decide how I want to react to being a caregiver. I think a lot of people forget that they can control how they feel about something. It helped to remind me that I have the power to choose.” “Helped me to stop and think about how I react to things.” “This webcast made me think about why we react the way we do. I realized based on what I’ve watched other people do that I had this unrealistic expectation of myself. This webcast helped to put things in perspective about what you can and cannot control.” |

| Creativity | “I liked the idea that we have the ability to create something out of what we think is nothing, that’s pretty cool.” “This webcast reminded me to take responsibility for my own life. If I don’t take care of myself, how can I take care of my son?” “I appreciated the concept that I can’t allow guilt to take away from my joy.” |

| Connectedness | “Showed me how we connect with the world around us in more ways than just relationships with other people. Sometimes it means connecting with nature or other creative expressions that you enjoy. This keeps us grounded and healthy.” “This was an interesting concept of being able to achieve transcendence without any effort. It showed me how to use my senses to achieve this.” “I enjoyed the nature aspect of this concept. I have always felt at ease and connected outside, and this concept helped describe this feeling I’ve always had.” |

| Perceived strengths of the workshop | “This intervention is helpful because it will let others know they are not alone.” “I’ve changed my lifestyle and have started thinking more about me and my health, and how that helps me help my loved one.” “It brought up things I was holding back or holding down. Participation helped bring things to the surface and it was better for me to deal with them.” “Program was a great source for information, and a place to find meaning in my caregiving role.” “The biggest lesson I learned from these webcasts is the importance of reaching out for help when you need it.” |

| Perceived weaknesses of the workshop | “I would have liked a discussion surrounding loss of interpersonal relationships and support systems.” “Every day is a rollercoaster; I am just too overwhelmed to participate.” “Not all caregivers were actively participating in the discussion boards at the same time; this made it difficult to interact.” “It is hard for caregivers to be away from the patient for a fixed period of time.” “I would have liked discussion boards to be broken down by diagnosis or relationship to patient.” |

| Accessibility of workshop | “The technology was easy for me to use considering I have no computer skills.” “Reminder emails from staff with the actual webcast links would have helped me navigate a little quicker.” “The language used on the website was clear and easy to comprehend.” “When I first logged on I was a bit confused. But once I spoke with the research assistant I was able to navigate the website easily.” “I wish the website was more accessible on my smartphone.” |

4 |. CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated the preliminary feasibility, acceptability, and effects of the CCC Workshop, the adaptation of MCP-C for delivery over the Internet. While there were no significant differences between groups in outcome variables examined, important trends emerged that are consistent with the goals of MCP-C. Moderate effect sizes emerged for meaning in caregiving and depressive symptomatology across time points, and in mixed-effects modeling, significant improvement in benefit finding emerged, all in favor of the CCC Workshop. Participants who engaged in the CCC Workshop showed increased benefit finding, the process by which individuals reassign positive value to challenging or traumatic events based on benefits identified.27 Benefit finding as a result of caregiving is well documented,31 and finding meaning is one mechanism through which such positive outcomes are achieved.8,32 The caregiving role may concurrently be a source of suffering and an experience that leads to adaptive coping, increased meaning, and growth. As such, we hypothesized that participation in the CCC Workshop would lead to enhanced benefit finding. Similarly, our results indicated greater increases in meaning derived from caregiving and decreased depressive symptomatology (compared to no change) among CCC participants. We anticipated that participants who completed the CCC Workshop would experience an enhanced sense of meaning and lower distress, including depressive symptomatology. While these reported differences were nonsignifi-cant, the effect sizes that emerged in this small sample are promising and will likely reach significance in larger trials. Importantly, as this is the first trial of any MCP intervention that is self-administered over the Internet, the emergence of these trends underscores the potency of MCP principles and techniques, and the potential impact of MCP interventions to improve the quality of life of ICs independent of modality.

Interviews completed by CCC Workshop participants support the abovementioned trends. ICs reported an increased ability to recognize their capacity for choice and enhanced control in caregiving. Highlighting ICs’ ability to choose how they respond to limitations and their capacity for pride in attitude taking is central to MCP-C. As such, decreases in depressive symptomatology among CCC participants are likely a result, in part, of this shifting perspective and participants’ recognition of efficacy and their ability to choose their attitude in the face of suffering. Similarly, increased benefit finding among CCC participants was reflected in responses such as “I liked the idea that we have the ability to create something out of what we think is nothing, that’s pretty cool.”

4.1 |. Clinical implications

Limitations to this study exist and restrict the generalizability of findings. The sample was primarily non-Hispanic White and of higher socioeconomic status, and we relied on participant report of patient medical characteristics instead of medical chart review. Our results were impacted by moderate attrition, though comparable to previous studies enrolling ICs.16,33–35 Attrition was higher in the CCC Workshop arm, which is expected as burden among ICs often prevents their engagement in support, independent of modality, and time requirements. Additionally, a greater proportion of CCC participants were caring for patients with Stage IV cancer than in the control arm. As the burden of care increases as disease progresses and patients transition from curative to palliative care, it is often more difficult for ICs to engage in self-care, which is likely reflected in our rate of attrition. Moreover, attrition was higher among male participants, which is consistent with previous studies of psychosocial interventions delivered in person13,36,37 and over the Internet.38–40 Importantly, the delivery of the CCC Workshop online in a self-administered fashion and/or challenges with using technology was not identified as a reason for attrition.

4.2 |. Conclusions and future directions

Psychosocial interventions are underutilized by cancer ICs, and the delivery of supportive services online can address common barriers to care. Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for cancer ICs delivered via the Internet in a self-administered, flexible format has the potential to improve a sense of meaning and purpose among ICs challenged with existential issues of suffering, responsibility, identity and guilt, and protect against burden.

The CCC Workshop was developed largely in response to the growing recognition of the many barriers ICs face in engaging in in-person psychosocial care. Each module was self-administered, which allowed for flexibility of timing, and research staff monitored engagement and encouraged continued use of the webcasts. Despite these facts, attrition remained comparable to studies of interventions delivered in-person to ICs. As such, it is important to consider how this workshop—and other targeted interventions for ICs—can be delivered in manner that is sensitive to the needs of this vulnerable population. For example, while the absence of any direct interaction with a mental health professional allowed for flexibility in administration, this may have been less appealing to ICs desiring direct contact with a professional. As such, the addition of at least one direct contact with a mental health professional may improve participant engagement in future studies. Moreover, attrition from the present study may also be a reflection of the workshop’s unique focus. While certainly the topics of self-care and facing challenges are applicable to all caregivers, the specific focus on meaning may not have resonated across ICs sampled. A targeted screening and enrollment process for ICs specifically challenged by existential distress and loss of meaning due to caregiving would likely address this potential contributor to attrition.

Nonetheless, there are opportunities for web-based MCP-C dissemination in supportive care environments where licensed professionals are not available for in-person support. An ideal example of this is the American Cancer Society’s Hope Lodge, which provides free lodging to patients and their ICs who to travel to receive treatment. As patients stay at Hope Lodge during active treatment, a time when ICs’ physical and psychosocial needs are great,18 having access to a self-paced intervention to alleviate distress could be an ideal mechanism to provide support and complement the various in-person support services offered at these facilities. Such an environment would also likely promote workshop engagement and address attrition seen here.

The telehealth movement has transformed the parameters of care delivery by making supportive services more accessible for ICs. With more than 68% of the population having access to a smartphone and 45% to a tablet [42], it is imperative that in the development of supportive programs, optimization for mobile platforms be considered paramount. Findings from this trial will inform future dissemination of the CCC Workshop, which has the potential to meet the unmet needs of ICs across the country.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Jaclyn Musum, BS, for her assistance in preparation of this manuscript. Funding for this study was provided by the American Cancer Society, grant no.: 12968, PI: Applebaum; NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support, grant no.: P30 CA008748, PI: Craig Thompson; and NIH/NCI, grant no.: T32 CA 009461, PI: Jamie Ostroff.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breitbart WS, Alici Y. Psycho-oncology. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009; 17(6):361–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Northouse L The impact of cancer on the family: an overview. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1985;14(3):215–242. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henoch I, Danielson E. Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: an integrative literature review. Psychooncology. 2009;18(3):225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applebaum AJ, Kryza-Lacombe M, Buthorn J, DeRosa A, Corner G, Diamond EL. Existential distress among caregivers of patients with brain tumors: a review of the literature. Neuro-Oncology Practice. 2015;3(4):232–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL, Wellisch DK. Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psychooncology. 2006;15(9):795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folkman S, Chesney MA, Christopher-Richards A. Stress and coping in caregiving partners of men with AIDS. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1994;17(1):35–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudson PL, Hayman-White K, Aranda S, Kristjanson LJ. Predicting family caregiver psychosocial functioning in palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2006;22(3):133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhoades DR, McFarland KF. Caregiver meaning: A study of caregivers of individuals with mental illness. Health Soc Work. 1999;24(4):291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Applebaum AJ, Breitbart W. Care for the cancer caregiver: a systematic review. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2013;11(03):231–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breitbart W, Poppito S, Rosenfeld B, Vickers AJ, Li Y, Abbey J. Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1304–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Applebaum A, Kuikowski J, Lichtenthal WG. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy: an effective intervention for improving psychological well-being in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(7):749–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Applebaum AJ, Kulikowski JR, Breitbart W. Meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C): rationale and overview. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2015;13(06):1631–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Applebaum AJ, Lichtenthal WG, Pessin HA, et al. Factors associated with attrition from a randomized controlled trial of meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(11):1195–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lichtenthal WG, Nilsson M, Kissane DW, et al. Underutilization of mental health services among bereaved caregivers with prolonged grief disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(10):1225–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dionne-Odom JN, Lyons KD, Akyar I, Bakitas MA. Coaching family caregivers to become better problem solvers when caring for persons with advanced cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2016;12(1–2):63–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuBenske LL, Gustafson DH, Kang N, et al. CHESS improves cancer caregivers’ burden and mood: results of an eHealth RCT. Health Psychol. 2014;33(10):1261–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Applebaum A, Farberov M, Teitelbaum ND, et al. Adaptation of meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C) for web-based delivery, in 13th Annual Conference of the American Psychosocial Oncology Society. 2016: San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farran CJ, Miller BH, Kaufman JE, Donner E, Fogg L. Finding meaning through caregiving: development of an instrument for family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55(9):1107–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reker G Manual of the Life Attitude Profile-Revised (LAP-R). Peterborough, ON: Student Psychologists Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15(4):271–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snaith R, Zigmond A. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6516):344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PPA, Kempen GIJM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(02):363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterman A, Fitchett G, and Cella D. Modeling the relationship between quality of life dimensions and an overall sense of well-being. in 3rd World Congress of Psycho-Oncology. 1996.

- 25.Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Galietta M. Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behr S, Murphy D, Summers J. User’s manual: Kansas Inventory of Parental Perceptions (KIPP). Lawrence, KS: Beach Center on Families and Disability; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20(1):20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London, England: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, et al. Positive changes among patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their family caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Health. 2016;1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farran CJ, Keane-Hagerty E, Salloway S, Kupferer S, Wilken CS. Finding meaning: An alternative paradigm for Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers. Gerontologist. 1991;31(4):483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2006;106(1):214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given B. A randomized, controlled trial of a patient/caregiver symptom control intervention: effects on depressive symptomatology of caregivers of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(2):112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boele FW, Hoeben W, Hilverda K, et al. Enhancing quality of life and mastery of informal caregivers of high-grade glioma patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurooncol. 2013;111(3):303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Hays JC, et al. Identifying, recruiting, and retaining seriously-ill patients and their caregivers in longitudinal research. Palliat Med. 2006;20(8):745–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudson P, Aranda S, McMurray N. Randomized controlled trials in palliative care: overcoming the obstacles. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001;7(9):427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Applebaum AJ, DuHamel KN, Winkel G, et al. Therapeutic alliance in telephone-administered cognitive–behavioral therapy for hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):811–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee EW, Denison FC, Hor K, Reynolds RM. Web-based interventions for prevention and treatment of perinatal mood disorders: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antypas K, Wangberg SC. An Internet-and mobile-based tailored intervention to enhance maintenance of physical activity after cardiac rehabilitation: short-term results of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]