Background

In the first month of the US COVID-19 epidemic, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was higher than that in 2017–2018 1. No studies have elucidated trends in the prevalence of depression and anxiety later in the pandemic.

Objective

To describe trends in the proportion of the US population for whom screening questionnaires indicate a high likelihood of depression or anxiety symptoms during the spring and summer of 2020.

Methods

We analyzed the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, a nationally representative survey of adults conducted between April 23 and July 21, 2020. The survey was administered to twelve samples covering about 13 weeks; households were interviewed for up to three consecutive weeks. Respondents completed a version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) questionnaires, both modified to assess the frequency of symptoms over one week rather than two. For both, a score of 3 indicates a high probability of the disorder when used in an outpatient setting 2. Weighted response rates ranged from 1.3 to 3.8% by week.

We conducted repeated cross-sectional analyses without linkage of individuals across sample weeks, and tabulated the proportion of respondents with PHQ-2 or GAD-2 score ≥3 in each survey week (hereinafter those with “positive screenings” for depression or anxiety).

We analyzed changes in prevalence from the first to the final week in our sample using linear probability regressions, and assessed differences between subgroups using regressions adjusted for a week indicator, a subgroup indicator, and a week*subgroup interaction term (Linear probability regression was chosen to facilitate interpretation of interaction terms). Subgroups included respondent race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, other), sex (male, female), family income (<$25,000; $25,000-$50,000, $50,000-$100,000, $100,000+), education (less than high school, high school, some college, or more), age in categories, and quintile of state-level COVID-19 incidence (measured by the 7-day moving average of new cases/100,000 on July 21 2020 3). For all analyses, we used Stata 16.1, sample weights from the Census Bureau to generate nationally representative estimates, and replicate weights to calculate standard errors.

Results

Of the 1,088,314 non-unique respondents to the survey, 988,349 (90.8%) completed the anxiety and depression screenings and were included in the study. Included participants had a mean age of 48.4 years and 51.5% were female.

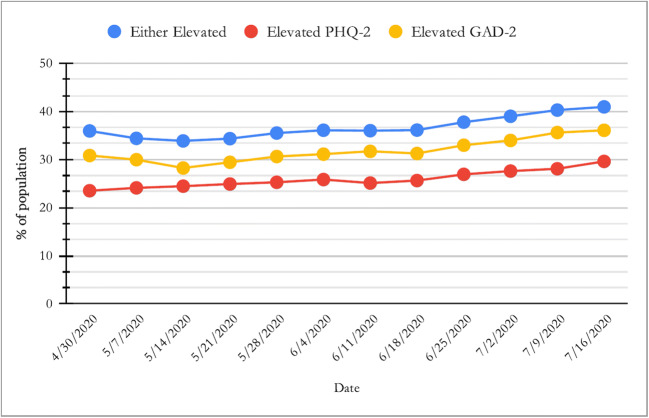

Figure 1 shows week-to-week trends in positive screenings for depression, anxiety, or either, which rose from 35.9 to 40.9% over the study period (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

“PHQ-2”=modified 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire. “GAD-2”=modified 2-item General Anxiety Disorder questionnaire. N=988,349. Depression/Anxiety Symptoms Rose During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Table 1 provides week 1–2 and week 13 estimates by subgroup. At both time points, women, younger individuals, racial/ethnic minorities, those with less education, and persons with lower incomes experienced higher rates of a positive screen for depression/anxiety. Table 1 provides adjusted difference-in-difference estimates. Men had a larger increase in depression/anxiety than women (2.1 percentage points, 95% CI 2.0, 2.2), as did individuals with family incomes $25,000–$50,000 relative to those with incomes ≥$100,000 (4.2 percentage points, 95% CI 1.8, 6.6). Individuals living in states with higher recent COVID incidence experienced larger increases in depression/anxiety relative to those in the lowest incidence quintile (p<0.001 for each comparison).

Table 1.

Positive Screening for Anxiety Was Defined as a Score of 3 or Higher on a Modified General Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) Questionnaire. DiD Difference in Difference. Positive Screening for Depression Was Defined as a Score of 3 or Higher on a Modified Patient Health Questionaire-2 (PHQ-2). *n=939,936. †COVID Per-Capita Infection Rate Was Calculated for Each State by Taking the Center for Disease Control’s 7-day Average of New COVID Cases as of July 21st (the Last Day of the Study Period) Divided by the State’s 2019 Population. Survey Respondents Were Then Divided into Quintiles Based on These Infection Rates

| Prevalence of positive screening for anxiety or depression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted results | Adjusted results | |||||

| April 23–May 5, 2020 | July 16–July 21, 2020 | Absolute change (95% CI) | p value | DiD estimate (95% CI) | p | |

| All respondents n=988,349 | ||||||

| 35.9 | 40.9 | 5.0 (4.6, 5.4) | <0.001 | NA | NA | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 31.0 | 37.0 | 6.1 (5.7,6.5) | <0.001 | Reference | – |

| Female | 40.7 | 44.6 | 4.0 (3.4,4.5) | <0.001 | −2.1 (−2.2, −2.0) | <0.001 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–44 | 41.9 | 49.3 | 7.5 (7.4,7.5) | <0.001 | 3.6 (3.6,3.7) | <0.001 |

| 45–65 | 35.7 | 39.5 | 3.8 (3.8,3.9) | 0.001 | Reference | – |

| 65+ | 23.6 | 25.4 | 1.8 (−0.30,3.9) | 0.09 | −2.0 (−4.0,.1) | 0.06 |

| Education | ||||||

| <HS | 45.4 | 47.3 | 2.0 (−0.40,4.3) | 0.10 | −2.9 (−5.4, −.38) | 0.02 |

| HS | 36.7 | 42.2 | 5.5 (4.0,7.1) | <.001 | .6 (−.68 , 2.0) | 0.34 |

| Some college | 34.5 | 39.4 | 4.9 (4.7,5.1) | <.001 | Reference | – |

| Race | ||||||

|

Non-Hispanic White |

33.6 | 38.8 | 5.3 (4.5,6.1) | <0.001 | Reference | – |

|

Non-Hispanic Black |

38.9 | 42.6 | 3.8 (3.2,4.4) | <0.001 | −1.5 (−2.9, −.10) | 0.04 |

|

Non-Hispanic Asian |

31.9 | 40.3 | 8.4 (2.5,14.3) | 0.006 | 3.1 (−2.0,8.2) | 0.23 |

|

Non-Hispanic Other |

43.9 | 48.8 | 4.9 (3.5,6.3) | <0.001 | −.4 (−.98,.17) | 0.16 |

| Hispanic | 42.7 | 46.3 | 3.6 (1.4,5.8) | 0.002 | −1.7 (−4.7,1.4) | 0.28 |

| 2019 family income * | ||||||

| <$25K | 51.0 | 54.1 | 3.1 (0.70,5.4) | 0.01 | −1.0 (−3.9, 1.9) | 0.52 |

| $25K–50K | 38.9 | 47.1 | 8.2 (6.4,10.1) | <0.001 | 4.2 (1.8,6.6) | 0.001 |

| $50K–100K | 34.3 | 37.7 | 3.4 (2.8,4.0) | <0.001 | −0.62 (−0.65, −0.59) | <0.001 |

| $100K + | 26.8 | 30.8 | 4.0 (3.5,4.6) | <0.001 | Reference | – |

| COVID infection rate in state† | ||||||

| Lowest quintile | 38.4 | 37.7 | −0.7 (−1.4, −0.02) | 0.04 | Reference | – |

| Quintile 2 | 35.3 | 41.1 | 5.8 (5.2,6.4) | <.001 | 6.5 (6.4,6.6) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 3 | 35.1 | 41.0 | 5.9 (4.2,7.6) | <.001 | 6.6 (4.2,9.0) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 4 | 34.8 | 44.2 | 9.4 (9.4,9.5) | <.001 | 10.1 (9.4,10.9) | <0.001 |

| Highest quintile | 35.8 | 42.2 | 6.4 (5.2,7.6) | <.001 | 7.1 (5.2, 9.0) | <0.001 |

Discussion

A substantial and rising share of the US population had positive screening tests for anxiety and depression symptoms during the spring and summer of 2020, amounting to 11.6 million more adults with mood symptoms over our study period. Although differential rates of increase between subgroups were modest, these results suggest a prevalence of depression/anxiety symptoms over three times that of 2019 baseline data 4.

Our study has limitations. Since the modified questionnaires in our study assessed for symptoms over one week rather than two, the sensitivities are likely higher and the specificities lower than the traditional PHQ-2 and GAD-2. Compositional changes in the survey sample or confounding events (such as reactions to the murder of George Floyd or the federal election) could contribute to observed trends. Our finding on the effect of COVID-19 rates rests on incidence over a single week. Finally, seasonal variation in mood is a potential concern; however, previous analyses show that mood symptoms do not typically worsen from spring to summer 4.

Our findings indicate that rates of mental distress were high, and worsened, during spring and summer 2020, and should serve as a reminder for practitioners to evaluate patients’ need for mental health care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. David Bor, Dr. Sam Dickman, Dr. Jessica Himmelstein, Dr. Danny McCormick, and Dr. Jenny Wen for their feedback on previous versions of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: None

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of Depression Symptoms in US Adults Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staples LG, Dear BF, Gandy M, et al. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of brief measures of depression, anxiety, and general distress: The PHQ-2, GAD-2, and K-6. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;56:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by State CDC COVID Data Tracker. Available at https://www.cdc. gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html#cases. Accessed September 10, 2020.

- 4.Early Release of Selected Mental Health Estimates Based on Data from the January–June 2019 National Health Interview Survey. e National Center for Health Statistics; 2020 Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/ERmentalhealth-508.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2021