Abstract

It is estimated that around 140 million people are drinking highly contaminated water with arsenic (As) as a natural earth’s crust component. On the other hand, the prevalence of neurodegenerative disorders, especially Alzheimer’s disease, is constantly increasing. The aim of the present study was to investigate the correlation between oral arsenic trioxide exposure and its impact on tau protein phosphorylation at Ser262. Fifty-four male mice were randomly divided into three groups and were freely accessed to food and contaminated water of 1 and 10 ppm arsenic trioxide for 3 months, except for control subjects. At the end of each month, As concentration and tau phosphorylation were checked with graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometer and western blot analysis, respectively. Surprisingly, it was observed that the amount of measured brain arsenic in 10 ppm-exposed subjects was significantly increased after 3 months (P-value ˂ 0.0001). The significant changes in tau phosphorylation were not seen in the 1 ppm-exposed subjects, and it was observed that Ser262 phosphorylation significantly increased after 2 and 3 months in the 10 ppm group (P-value < 0.05). Our results demonstrated that arsenic accumulated in the brain time-dependently and increased Ser262 tau phosphorylation, which is very important in several tauopathies. In conclusion, it could be inferred that environmental arsenic exposure even at very low concentrations could be considered as a reason for increasing the risk of developing neurodegenerative disease.

Keywords: arsenic, tau, phosphorylation, neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer, water contamination

Introduction

The industrial revolution is one of the most critical events which cause environmental pollution with serious impacts on human’s health [1]. One of the most environmental pollutants is heavy metals, especially arsenic, with a various source of exposure including air, drinking water, food and smoking. Arsenic is a widely distributed metalloid as a natural earth’s crust component, which is highly present in the groundwater of Argentina, China, India, Bangladesh, Chile and the USA [2, 3].

It is one of 10 chemicals that World Health Organization (WHO) ranked as major public health concerns, and it has been estimated that around 140 million people in 50 countries are drinking arsenic-contaminated water at levels higher than the allowed value of 10 μg/l. Contaminated water poses the greatest threat to public health because it can be used for drinking, food preparation and irrigation of crops [4].

This metalloid is highly toxic in its inorganic form than the organic species. Short-term exposure to arsenic can cause acute poisoning symptoms like gastrointestinal disturbance, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and muscle weakness. Chronic exposure to high levels of inorganic arsenic has also been associated with more serious problems, such as liver, kidney, bladder and cardiovascular damages. Besides, induction of various cancers, diabetes or cognitive development impairment is a much bigger problem of chronic arsenic exposure in comparison to acute exposure [5, 6].

Tau is a family of neuronal proteins that act as a major microtubule-associated protein (MAP), and it can promote the assembly and stability of microtubules. They are mainly expressed in neural cells and posse’s regulatory effects in the organization of the cytoskeleton network and can regulate by its phosphorylation state. It was observed that tau hyperphosphorylation decreased its biological activity [7–9].

Also, it has been shown that tau phosphorylation at specific positions results in intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles deposits in almost 80 diseases, especially neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Argyrophilic grain disease, etc. Early studies indicated that arsenic can increase the phosphorylation of tau in rats and contribute to the destabilization and disruption of the cytoskeletal frameworks [10–13].

In the light of these observations, the aim of the present study was to investigate the correlation between arsenic trioxide exposure as an inorganic arsenic form and its impact on the tau protein Ser262 phosphorylation after 3 months of exposure via drinking water in male mice.

Material and Methods

Arsenic trioxide (99%, lot no. 02556EN) used in this experiment was obtained from the Sigma Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc (Allentown, PA, USA). All reactants consumed were chosen from analytical grades and were acquired from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), except those that are mentioned later. After complete immersion of all plastic instruments and glassware for 24 h in 2 M nitric acid, they were rinsed with deionized water. A Milli-Q Ultrapure deionized water was used. Β-actin antibody (sc47778), anti-tau (ab75714) and phospho S262 antibody (ab131354), protein size marker and Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) western blotting membrane were purchased from Santacruz, Abcam, Thermo and Roche, respectively.

Experimental design

All animal studies were carried out according to the approved guidelines of the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee at the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Fifty-four male mice (20 ± 5 g) in housed polypropylene cages were put into a room temperature of 23 ± 5°C with an approved light/dark cycle (proper humidity), with free access to food and water. After 5 days of acclimatization period, subjects divided randomly into three groups. As shown in Fig. 1, Groups I and II were given arsenic trioxide dissolved in drinking water (1 and 10 ppm, respectively) ad libitum and the remaining animals that were considered as a control group were given normal drinking water for 3 months.

Figure 1.

A brief review of study experimental design. Fifty four male mice were randomly divided to three groups in which group 2 and 3 were espoused to arsenic trioxide contaminated water (1 and 10ppm, respectively) for 3 month. After each month 6 mice were randomly checked for serum and brain arsenic concentration and tau protein Ser262 phosphorylation.

Arsenic preparation and sampling

We provided arsenic-containing drinking water twice a week and diluted it to reach a desirable concentration. It is worth mentioning that NaOH (1 M) was used in order to make the arsenic trioxide soluble and was then neutralized with HCl to an appropriate pH. Diluted samples, diet pellets and tap water were regularly checked for the total arsenic concentration. In addition, animals were also checked for body weight at a certain time during morning hours weekly. At the end of the 4th, 8th and 12th weeks of exposure, we terminated six animals of each group by cervical decapitation and collected the whole blood via vacutainer, allowed the samples to clot for 1 h and then centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 g to isolate the serum samples. The brains were then taken out instantly, rinsed and sectioned coronally, then the hippocampus region of each hemisphere was stored at −80°C for further evaluations.

Arsenic measurement

An atomic absorption spectrometer (Varian model 220-Z) infected with a graphite furnace atomizer (GTA-110) with a Zeeman background correction was used to evaluate the total concentration of arsenic (atomizing temperature was 2100 with a holding time of 5 s). We used argon as a sheet gas in all stages of determination except for during the atomization stage that the purge gas flow was banned. Absorbance values of both peak height and peak area were measured in triplicate for all standard and samples throughout the procedure [14].

For sample preparation and acid digestion, we used concentrated HNO3: 65%, H2O2: 30% and HCL: 37%. During the measurement stage, we applied a 1 g.l−1-concentrated arsenic stock solution (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) to prepare a 100 mg.l−1 standard solution. In order to validate the proposed method, we applied commercially purchased quality control solutions (certified reference materials) known as CRM (QA level 200, NIES, Japan) in the experiment. Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were estimated to be 1 and 10 μg.l−1, respectively. Recovery of the method was in a range of 80–110% at the concentrations of LOQ (10 μg.l−1) and 10 × LOQ (100 μg.l−1). Repeatability relative standard deviation (RSDr) and reproducibility relative standard deviation (RSDR) were calculated at the different concentrations of inorganic arsenic. The RSDr was in a range of 5–8.3% and the RSDR was in a range of 12.1–30%.

Sample preparation and western blot analysis

The amount of phosphorylated tau and total tau proteins in homogenous brains were evaluated using western blot analysis. Brain tissues from treated and untreated mice were homogenized in 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Santa Cruz, USA) supplemented within protease and phosphatase inhibitor using a Micro Smash MS-100. A gel loading buffer (0.25 M Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 5% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 3% SDS and 0.2 mg/ml bromophenol blue) were added to the homogenates and were heated to 95°C for 5 min. After sample preparation, protein samples (20 μg/well) were separated by SDS-PAGE (80 v for 5% stacking gel and 150 v for 12% running gel). Then, proteins were electrophoretically transferred (100 v, h) from gels to PVDF membranes (Rouch, USA) using the Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (USA). The membranes were incubated in a blocking buffer containing 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and Tween 20 (TBST) for 60 min at room temperature. Then, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies [anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz, USA), anti-tau (Abcam, USA) and anti-phosphorylated tau (Abcam, USA) antibodies] in skim milk at 4°C for overnight. Removal of the unbounded primary antibody was carried out by three times washing of the membranes in TBST for 10 min. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody [peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Abcam, USA)] for 1 h at room temperature and then washed with TBST three times. Finally, the membranes were incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) solutions [Luminescence substrate solution A (Luminol), Starting solution B (H2O2)], and the visualized bonds were photographed by PhotoDoc Imaging system (Germany). To quantify the amount of phosphorylated tau and total tau proteins, the signal intensities of bands were determined using ImageJ software and normalized using the intensity of the β-actin band at the corresponding doses and times [15].

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times to ensure reproducibility of the results. Data are expressed as means ± SD. GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for data processing and statistical evaluation. Differences between the groups were evaluated with analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey post hoc test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Body weight

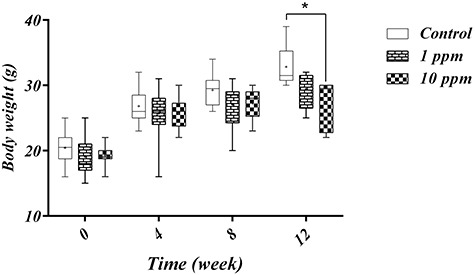

As shown in Fig. 2, the mean body weight of the subjects at the beginning of the study was not statistically significant between groups (P-value > 0.05). Also, a positive correlation regarding the time of exposure and weight change was observed in all groups based on the Spearman correlation test (r: 0.989). However, after 2 months of exposure, it was observed that 10 ppm-exposed subjects had a zero net growth rate with statistically significant differences as compared to the control group (P-value < 0.05). It should be noted that obvious physical changes or toxicity were not observed at this level of arsenic trioxide exposure after 3 months.

Figure 2.

Arsenic trioxide was given in drinking water as 1 ppm and 10 ppm for 12 weeks. Control group subjects were given tap water ad lib. The body weights were taken each week. A positive correlation between time and weight gain was observed in all groups however, at the end of study 10ppm arsenic treated subjects had significantly lower body weight as compared to the control group. Data are presented as min to max during every month of study. + Means and * p-value < 0.05.

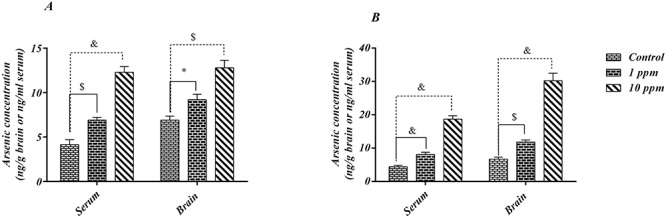

Arsenic concentration

Arsenic concentrations in the serum and brain samples after the first and third month of the study are presented in Fig. 3A and B. A significant and positive relationship between the arsenic concentration and time of exposure were observed in all groups. In general, the amount of measured arsenic in the brain was higher than the serum level in all groups of study regardless of the time of measurement; the only exception was the control group at the end of the study (P > 0.05). Surprisingly, it was observed that the amount of measured brain arsenic in 10 ppm-exposed subjects was significantly increased after 3 months (P-value ˂ 0.0001). Meanwhile, in 1 ppm-exposed subjects, arsenic was not significantly changed.

Figure 3.

Arsenic concentration in brain (ng.g-1) and serum (ng.ml-1) of each group subjects after 4 and 12 weeks exposure to arsenic trioxide in drinking water (1 and 10 ppm). Part A represented the values after 4 weeks of exposure and B represented the arsenic contents at the end of study after 12 weeks. Data were presented as Mean ± SD. Statistically significant differences were examined by Two-way F test followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05; $p < 0.001; &p < 0.0001.

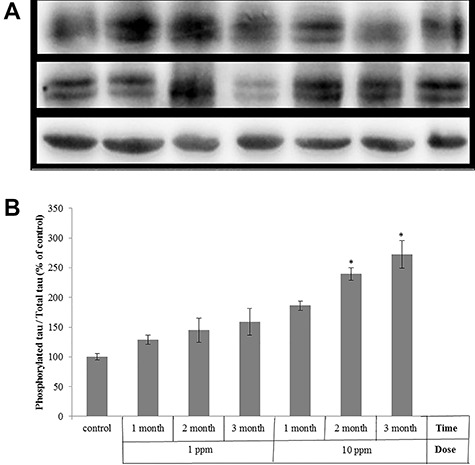

Tau phosphorylation

Homogenous brains of mice were analyzed by western blot using anti Tau and anti phospho-Tau (S262) antibodies. As shown in Fig. 4A, brain samples from both groups which were treated with 1 or 10 ppm of arsenic trioxide were found to have relatively higher levels of tau (Ser262) phosphorylation compared with the untreated group (control). However, chronic arsenic exposure did not significantly change the total tau protein level (data not shown). The amount of phosphorylated tau and total tau proteins was quantified using signal intensities of bonds and was normalized using the intensity of β-actin, which were analyzed by densitometry. Then, the relative changes in the ratio of phosphorylated tau to total tau compared with control were calculated. It was found that the increase in phosphorylated tau levels was more significant (P < 0.05) in the 10 ppm-exposed subjects (Fig. 4B). Time-course experiments with 10 ppm treatment exhibited significant (P < 0.05) increase in the phosphorylation of tau in 2 and 3 months compared to the control. No significant change in phosphorylation of tau was observed in mice treated with 1 ppm for 1, 2 and 3 months, compared to the control.

Figure 4.

Time- and dose-dependent phosphorylation of tau by chronic arsenic exposure in mice brain. Mice were treated with arsenic trioxide dissolved in drinking water ad lib (1ppm and 10 ppm) for 1, 2 and 3 months, or non-treated (control), and homogenous brains of mice were analyzed by Western blot using anti-tau and anti-tau (phospho S262) antibodies. a) Representative Western blot, b) The amount of phosphorylated tau and total tau proteins were quantified using signal intensities of bonds. Results are presented as the Mean ± SEM of phosphorylated tau / total tau compared with the control. (n = 4, *p < 0.05 vs. control).

Discussion

We observed that arsenic accumulated in the brain after 3 months of exposure and it was significantly correlated to an increased tau phosphorylation at Ser262. This observation is very important because many of the studies done before suggested that arsenic is correlated with the neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s disease; meanwhile, around 140 million people in 50 countries worldwide are exposed to arsenic-contaminated water, which is higher than the WHO-allowed range [16, 17].

Arsenic is a widely distributed metalloid in the earth’s crust, which is acutely toxic in its inorganic form, specially trioxide. Water is the most prominent source for arsenic exposure. The two major inorganic forms that act as water contaminants are arsenite and arsenate [18, 19]. In our study, it was observed that arsenic trioxide exposure in drinking water even with 10 ppm concentration for 12 weeks did not cause any serious clinical or physical signs, including paralysis, obvious depression, locomotor activity changes or excessive weight loss. Several authors have reported that oral arsenic trioxide with different time of exposures had a dual effect on the neurobehavioral signs, which is mainly dependent on the dose of exposure. For instance, 3 mg/kg body weight for 2 weeks increased the mice locomotor activity, while 10 mg/kg acts vice versa [20, 21].

About weight change, it should be noted that all of the study subjects had a positive correlation with respect to the weight change during the time of the study. However, at the end of the study, subjects treated with 10 ppm arsenic had shown a lower weight gain as compared to the normal control. This observation confirmed the previous study which reported that rats lose their body weight after 3 months of oral arsenic exposure [22]. One of the suggested mechanisms for weight reduction could be the disruption in essential nutrient absorption and cellular energy impairment due to arsenic toxicity [23].

Analyses of the normal food pellets and drinking water reported that the arsenic concentration was lower than 10 % of the administrated values. It was observed that, in all groups, arsenic concentration in the brain samples was higher than the serum level, especially in 10 ppm-treated subjects after 3 months of exposure. At first, it should be mentioned that transporters such as aquaporins (AQP7 and AQP9), glucose transporter (GLUT1 and GLUT4) and phosphate transporters (NaPi) play a critical role in arsenic absorption from the gastrointestinal tract and blood-brain barrier. Previous studies reported that trivalent arsenic act as specific organic molecules such as glycerol and flux to the brain via specific aquaglyceroporins [24]. However, recently, it was reported that chronic arsenic exposure leads to BBB leakage with an excessive release of S100B protein to the serum. So, the elevated arsenic content in the brain after 3 months of exposure could be explained due to suspected BBB integrity disturbance [25].

Surprisingly, we observed that in accordance with the elevation of brain arsenic content during the time of exposure, tau phosphorylation at Ser262 was increased. Tau is a substrate for many protein kinases which its abnormal phosphorylation results are tau dysfunction and pathological conditions including Alzheimer and neurodegenerative disorders [8]. Glycogen synthase kinase 3B (GSK3B), which is highly expressed in the brain, MARK, PKA, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5), is highly related to the in vivo phosphorylation of tau residue. It was reported that arsenic inhibits p21 expression via GSK-3β phosphorylation in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Also, rat neural cell primary culture showed that cdk5 was highly expressed after treatment with 5 and 10 μM/l of As2O3. When Cdk5 hyperactivates, it can cause the hyperphosphorylation of tau and amyloid precursor proteins, resulting in neurofibrillary tangles formation, mitochondrial imbalance and neurodegeneration [26–31].

Binding and stabilizing of microtubules is a specific hallmark of tau proteins activity, in which, site-specific phosphorylation could regulate its interaction to microtubules. Many studies have suggested that tau phosphorylation at Ser 262 is significantly sufficient to decrease the interaction of the microtubule of tau protein, which leads to increase its cytosolic unbound form. Tau phosphorylated at Threonine 231 or Ser 262 to form a rectangle in Alzheimer’s disease, which can be cleaved subsequently or further phosphorylated at Ser 422, 396 and 404 for additional oligomerization and aggregation in other tauopathies [26, 32].

It was shown that gestational arsenic exposure via drinking water leads to significant spatial memory loss in offsprings. Also, in several European countries, including Switzerland, Spain, France, Belgium and Norway, with a higher arsenic exposure (18 ppm), prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease was higher than in countries with a lower arsenic exposure (<9 ppm), such as Luxemburg, Denmark, Finland and Netherlands [33]. It was reported that in vivo tau phosphorylation at Ser262 is very important for amyloid beta-induced toxicity [34]. Recently, it was observed that tau phosphorylation at Ser 262 is crucial for amyloid beta 42-induced taopathies [34, 35]. Also, in the EAE model of multiple sclerosis, it was reported that tau phosphorylation is associated with the progression and axonal loss in the relapsing phase of the disease [6, 25, 36].

To date, the prevalence of dementia has been estimated around 24 million worldwide, in which, Alzheimer’s disease with the neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques form in the brain is the main cause of dementia [37]. The exact etiology of Alzheimer’s disease was unknown; however, it is almost correlated to the interaction between the genetic background and environmental factors. As it was mentioned before arsenic expected as a major environmental pollutant [38, 14, 39, 40].

Conclusion

To put on the hole, our results demonstrated that arsenic accumulated in the brain time-dependently, which could be the result of BBB integrity disruption which is based on the previously published data about elevation in serum S100B concentration. Also, it was found that tau phosphorylation at Ser262 was increased significantly after 3 months of exposure to 10 ppm arsenic trioxide via drinking water. In conclusion, it could be inferred that environmental arsenic exposure even at very low concentrations could be considered as a reason for increasing the risk of developing neurodegenerative disease.

Funding

This work was supported by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Pharmaceutical Research Center (grant number 396772).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Ethics approval

All procedures were approved by the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research and were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Contributor Information

Davoud Pakzad, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Isfahan 81746-73461, Iran.

Vajihe Akbari, Department of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Pharmacy, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Isfahan 81746-73461, Iran.

Mohammad Reza Sepand, Department of Toxicology and Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Tehran 81746-73461, Iran.

Mehdi Aliomrani, Department of Toxicology and Pharmacology, Isfahan Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Isfahan 81746-73461, Iran.

References

- 1. Candelone J, Hong S, Pellone C. et al. Post-industrial revolution changes in large-scale atmospheric pollution of the northern hemisphere by heavy metals as documented in central Greenland snow and ice. J Geophys Res Atmos 1995;100:16605–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hopenhayn C. Arsenic in drinking water: impact on human health. Elements 2006;2:103–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wei S, Zhang H, Tao S. A review of arsenic exposure and lung cancer. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2019;8:319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mochizuki H, Phyu KP, Aung MN. et al. Peripheral neuropathy induced by drinking water contaminated with low-dose arsenic in Myanmar. Environ Health Prev Med 2019;24:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuo C-C, Moon KA, Wang S-L. et al. The association of arsenic metabolism with cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Environ Health Perspect 2017;125:87001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aliomrani M, Sahraian MA, Shirkhanloo H. et al. Correlation between heavy metal exposure and GSTM1 polymorphism in Iranian multiple sclerosis patients. Neurol Sci 2017;38:1271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maeda S, Mucke L. Tau phosphorylation—much more than a biomarker. Neuron 2016;92:265–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanger DP, Anderton BH, Noble W. Tau phosphorylation: the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends Mol Med 2009;15:112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen D, Drombosky KW, Hou Z. et al. Tau local structure shields an amyloid-forming motif and controls aggregation propensity. Nat Commun 2019;10:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Augustinack JC, Schneider A, Mandelkow E-M. et al. Specific tau phosphorylation sites correlate with severity of neuronal cytopathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 2002;103:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ikeda C, Yokota O, Nagao S. et al. The relationship between development of neuronal and astrocytic tau pathologies in subcortical nuclei and progression of argyrophilic grain disease. Brain Pathol 2016;26:488–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vagnozzi AN, Li J-G, Chiu J. et al. VPS35 regulates tau phosphorylation and neuropathology in tauopathy. Mol Psychiatry 2019;25:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13. Hashimoto S, Matsuba Y, Kamano N. et al. Tau binding protein CAPON induces tau aggregation and neurodegeneration. Nat Commun 2019;10:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Azami K, Aliomrani M, Mobarake MD. Cadmium separation in human biological samples based on captopril-ionic liquid paste on graphite rod before determination by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal Methods Environ Chem J 2019;2:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bramblett GT, Goedert M, Jakes R. et al. Abnormal tau phosphorylation at Ser396 in Alzheimer’s disease recapitulates development and contributes to reduced microtubule binding. Neuron 1993;10:1089–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Costa JJ, Maniruzzaman M. Detection of arsenic contamination in drinking water using color sensor. In: 2018 International Conference on Advancement in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ICAEEE). Piscataway, New Jersey: IEEE, 2018, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sen R, Sarkar S. Arsenic contamination of groundwater in West Bengal: a report. In: Waste Management and Resource Efficiency. Singapore: Springer, 2019, 249–59. [Google Scholar]

- 18. He T, Ohgami N, Li X. et al. Hearing loss in humans drinking tube well water with high levels of iron in arsenic–polluted area. Sci Rep 2019;9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saha JC, Dikshit AK, Bandyopadhyay M. et al. A review of arsenic poisoning and its effects on human health. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 1999;29:281–313. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodríguez VM, Limón-Pacheco JH, Carrizales L. et al. Chronic exposure to low levels of inorganic arsenic causes alterations in locomotor activity and in the expression of dopaminergic and antioxidant systems in the albino rat. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2010;32:640–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tadanobu I, Zhang YF, Shigeo M. et al. The effect of arsenic trioxide on brain monoamine metabolism and locomotor activity of mice. Toxicol Lett 1990;54:345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nandi D, Patra RC, Swarup D. Oxidative stress indices and plasma biochemical parameters during oral exposure to arsenic in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2006;44:1579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holson JF, Stump DG, Clevidence KJ. et al. Evaluation of the prenatal developmental toxicity of orally administered arsenic trioxide in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2000;38:459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hughes MF, Kenyon EM, Edwards BC. et al. Accumulation and metabolism of arsenic in mice after repeated oral administration of arsenate. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2003;191:202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Golmohammadi J, Jahanian-Najafabadi A, Aliomrani M. Chronic oral arsenic exposure and its correlation with serum S100B concentration. Biol Trace Elem Res 2019;189:172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong C-X. Tau and neurodegenerative disease: the story so far. Nat Rev Neurol 2016;12:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martin L, Latypova X, Wilson CM. et al. Tau protein kinases: involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12:289–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferrer I, Barrachina M, Puig B. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is associated with neuronal and glial hyperphosphorylated tau deposits in Alzheimer’s disease, Pick’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 2002;104:583–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ulrich G, Salvadè A, Boersema P. et al. Phosphorylation of nuclear tau is modulated by distinct cellular pathways. Sci Rep 2018;8:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paknejad B, Shirkhanloo H, Aliomrani M. Is there any relevance between serum heavy metal concentration and BBB leakage in multiple sclerosis patients? Biol Trace Elem Res 2019;190:289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu C-W, Lin P-J, Tsai J-S. et al. Arsenite-induced apoptosis can be attenuated via depletion of mTOR activity to restore autophagy. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2019;8:101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kolarova M, García-Sierra F, Bartos A. et al. Structure and pathology of tau protein in Alzheimer disease. Int J Alzheimer’s Dis 2012;2012:117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dani SU. Arsenic for the fool: an exponential connection. Sci Total Environ 2010;408:1842–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iijima K, Gatt A, Iijima-Ando K. Tau Ser262 phosphorylation is critical for Aβ42-induced tau toxicity in a transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:2947–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alonso AD, Di Clerico J, Li B. et al. Phosphorylation of tau at Thr212, Thr231, and Ser262 combined causes neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem 2010;285:30851–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schneider A, Araújo GW, Trajkovic K. et al. Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Biol Chem 2004;279:55833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2011;7:137–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L. et al. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sepand M-R, Aliomrani M, Hasani-Nourian Y. et al. Mechanisms and pathogenesis underlying environmental chemical-induced necroptosis. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020;27:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aliomrani M, Sahraian MA, Shirkhanloo H. et al. Blood concentrations of cadmium and lead in multiple sclerosis patients from Iran. Iran J Pharm Res IJPR 2016;15:825. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]