Abstract

Purpose of Review

This study aims to assess the current state of cardio-oncology in reference to advocacy efforts, access to care, and perspective of stakeholders in their ability to provide patient care as well as development of “across the aisle” synergy among cardiologists and oncologists and academic and non-academic centers in various worldwide locations.

Recent Findings

During the last decade, there has been a significant and diverse growth in cardio-oncology. We reviewed the experience from cardiologists and oncologists across different healthcare systems, the global trends, the role of collaborative networks, and the importance of advocacy efforts.

Summary

Cardio-oncology will continue to grow, but there is an unmet need to increase awareness, improve education, and expand access to care to larger segments of the cancer population in order to have a more significant impact on their health. The growing collaboration through professional societies and collaborative networks provides an opportunity to advance the cardiovascular care of cancer patients to meet the projected needs in a growing and more diverse population.

Keywords: Cardio-oncology, Advocacy, Healthcare

Introduction

There are currently 17 million cancer survivors in the USA [1]. Cancer patients have a 2–6 times higher cardiovascular mortality risk than the general population, and cardiovascular mortality is evident throughout the continuum of cancer care [2••]. With effective cancer treatments and declining cancer-related mortality, cardiovascular disease management and access to it become even more important [2••, 3] Multiple factors result in decreased healthcare access and poor outcomes for these patients [4]. Cardio-oncology as a subspecialty initially developed with the leadership of oncology within several Canadian provinces through the Canadian Cardio-Oncology Network (CCON). However, in most of the world and within the USA, cardio-oncology has really grown in strength and numbers as a result of the leadership of cardiologists. Numerous cardio-oncology programs have emerged to meet these demand needs but remain confined to larger institutions, which are often academic referral centers [5]. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)’s National Cardio-Oncology Survey [6] identified specific barriers to the implementation of cardio-oncology programs, including lack of educational opportunities, limited interest, lack of infrastructure, and lack of funding. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardio-oncology barriers (American College of Cardiology Survey)

| Barriers | Examples | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| - Lack of national guidelines | - No formal ACC AHA guidelines |

- ASCO guidelines - SCAI documents - ASE EACVI consensus document multimodality imaging |

| - Absence of funding |

- Lack of institutional resources for programs - Lack of research funding |

- Increased institutional awareness based on patient data - Advocacy and engagement with NIH and funding agencies |

| - Limited interest | - Currently less of a problem, given rapid growth of cardio-oncology | - Has been reversed by dedicated committees by the ACC, ASCO, AHA, ESC, BCOS, and others |

| - Limited educational opportunities | - The number of educational activities increased dramatically in the last 5 years |

- ACC Cardio-Oncology Conference, MSKCC, GCOS Annual Conferences - Dedicated ACC, AHA, ASCO, and ESC sessions in scientific meetings - Multiple conferences and webinars - Journals: JACC Cardio-Oncology, and Cardio-Oncology Journal (ICOS) |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; SCAI,: Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention; ASE, American Society of Echocardiography; NIH, National Institutes of Health; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; BCOS, British Cardio-Oncology Society; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; GCOS, Global Cardio-Oncology Summit; JACC, Journal of the American College of Cardiology; ICOS, International Cardio-Oncology Society

An additional limitation to more widespread expansion of cardio-oncology practices is the fact that several cardiovascular testing indications may not covered by medical insurance providers as designated codes do not exist. Examples include postradiation noninvasive cardiac testing for surveillance, biomarkers during chemotherapy treatment, and cardiac magnetic resonance used for early detection of cardiac effects of cancer-related therapies.

Herein, we provide an overview of the current landscape of cardio-oncology programs across the globe and the needs to allow an even broader uptake by all who would like to start such as program.

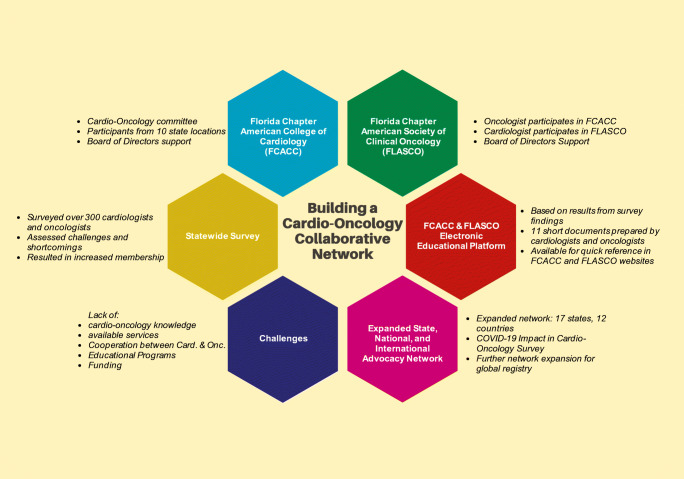

Building Local Cardio-Oncology Programs and Networks to Improve Access to Care

There is a need to improve access to care at the local, state, and national level. For instance, in the state of Florida, we recently reported a practical model to start and maintain a successful cardio-oncology program without additional financial resources that can be reproduced in a variety of different practice settings to improve access to this specialized level of care [7•]. Programs in the community can only succeed with active participation and engagement with professional societies. In September 2018, the state of Florida hosted the International Cardio-Oncology Society (ICOS) Global Cardio-Oncology Summit (GCOS) in Tampa. Case presentations shared during that meeting highlighted the widespread lack of awareness and education in cardio-oncology in the larger medical community. Members of the Florida Chapter of the American College of Cardiology (FCACC) assembled a cardio-oncology committee and “reached across the aisle” to medical oncologists who joined the FCACC to serve in the committee. The committee engaged on a collaboration between the FCACC and the Florida Chapter of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (FLASCO) and developed a collaborative program to assess the educational needs of both cardiologists and oncologists (Fig. 1). A statewide survey utilizing the electronic platforms of the FCACC and the FLASCO revealed that even among the more engaged group of physicians that responded to the survey, there was a remarkable lack of knowledge, awareness, cooperation between cardiologists and oncologists, and even lack of knowledge on cardiotoxicity of commonly used chemotherapy regimens in cancer patients [8••]. It also emphasized the need for more cardio-oncology programs. Based on the survey results, educational materials were developed to help bridging the identified knowledge gaps. Those materials are a source for rapid consultation for practitioners and are available at the websites of the FCACC and the FLASCO [9].

Fig. 1.

This figure describes the collaborative partnership between cardiologists and oncologists initiated in the state of Florida and expanded to form a national and international advocacy network

Based on the Florida experience, the next step was to evaluate the same questions and concerns in a variety of geographic locations utilizing a large, multistate network that includes members from 19 ACC state chapters, 6 ASCO chapters, and 9 countries with chapters that are affiliated with the International Cardio-Oncology Society with participants from both academic and private practice settings. This network is a platform for multiple collaborations. The plans for growth of our collaborative network were altered by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Therefore, the first project was to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the practices of cardiologists and oncologists and its effects on the reallocation of resources for elective procedures, testing, scheduling, access to telemedicine services, the early utilization of new COVID-19 therapies, and providers’ opinions on healthcare national healthcare policies [10•].

The results exposed some of the shortcomings of the existing healthcare system and its impact on healthcare providers and their ability to provide optimal care to their patients in the context of a healthcare crisis. There was an almost unanimous support by cardiologists and oncologists, academic and non-academic doctors, and doctors in a variety of geographic settings, for the need for national healthcare policies for containment of the epidemic as well as the strong support for further involvement and participation of professional medical societies on decision-making to drive data-based healthcare policies to be implemented by governments for preparedness and response for current and future healthcare crisis.

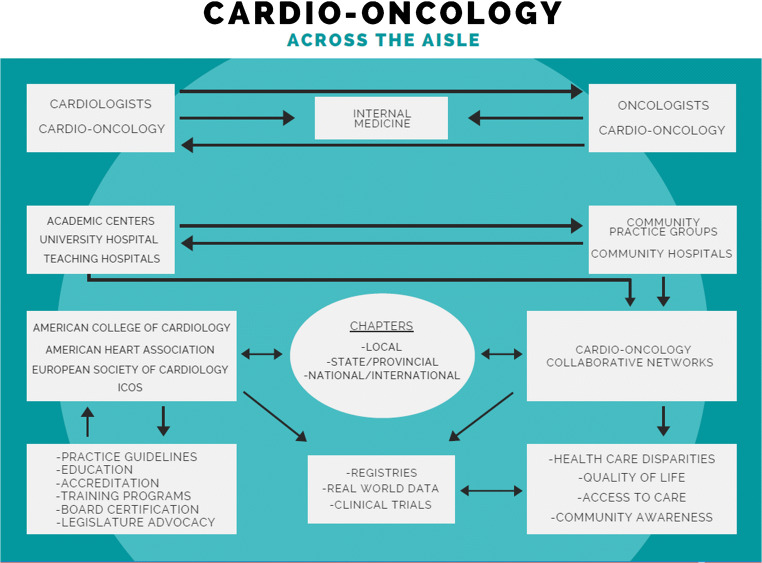

These initial projects by our cardio-oncology multistate and international collaborative network highlights the role of collaborative networks in being active players in expanding advocacy and education in cardio-oncology (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This figure illustrates the interaction between stakeholders in cardio-oncology and the collaborations needed to occur among physicians, professional medical associations, academic and community centers/practices, and collaborative networks to expand education, awareness, and access to care in cardio-oncology. ICOS, International Cardio-Oncology Society

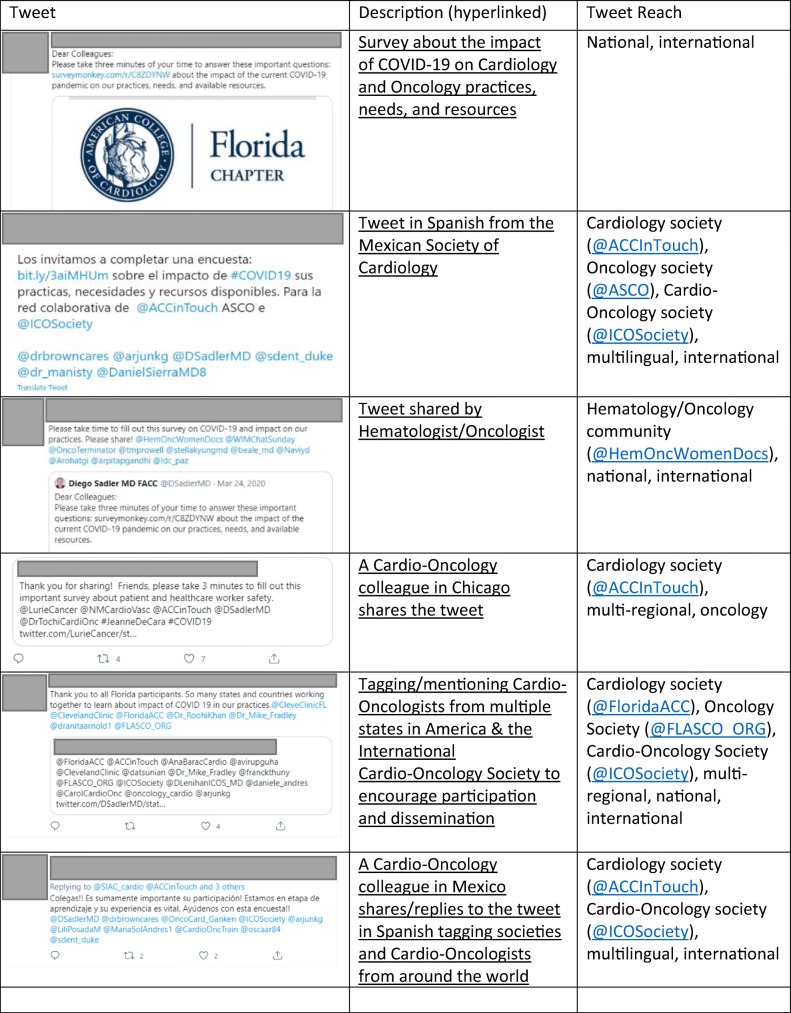

The Role of Social Media in Advocacy

For the outlined project on the impact of COVID-19 on cardiology and oncology practices, social media was critical to disseminate the survey, particularly on Twitter (Table 2). Twitter is a social network and microblogging website and mobile app (www.twitter.com). Users can post and respond to messages known as “tweets,” which are limited to 280 characters. Users can follow other users or organizations. Tweets can be categorized by hashtags, which can also be searched and followed, for example, #CardioOnc. A sample of 5 tweets about the survey originated in the USA yielded almost 8000 impressions (number of times tweet was seen by other individuals on Twitter) combined, with engagement of cardiologists and oncologists in cardio-oncology reaching across the USA and around the world. Tweets were crafted in multiple languages to reflect the international nature of the survey. The sentiments expressed in the tweets were literally inviting and also shared thoughts of gratitude, collaboration, and community. Both the International Cardio-Oncology Society (@ICOSociety) and the American College of Cardiology (@ACCInTouch), long-time partners in cardio-oncology, were tagged or mentioned in the tweets, as were the national cardiology societies for various countries appropriately matched to the language of the tweet. For example, the Argentinian Cardiology Society (@SAC_54), the Argentinian Cardio-Oncology Council (@CardioOncoSAC), and the Mexican Cardiology Society (@SMexCardiologia) were tagged or mentioned in the tweets crafted in Spanish. Similarly, for the tweets in English, regional groups were mentioned or tagged. The Florida chapters of the American College of Cardiology (@FloridaACC) and the American Society for Clinical Oncology (@FLASCO_ORG) were tagged in the tweets encouraging and thanking Florida participants while at the same time verbally referring to the national and global community of states and countries banding together to overcome the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tweets from other countries disseminating the survey also reached across boundaries. A tweet from a cardio-oncology leader in Mexico was crafted in Spanish, informing readers of the tweet that their participation was vital to sharing their voices in the survey results. Participants in the USA, Mexico, the UK, Canada, Argentina, and Japan were tagged or mentioned in the tweet, as were the Interamerican Society of Cardiology (@SIAC_cardio) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (@ICOSociety). Such international unity may have helped with survey participation. One may therefore conclude that community, collaboration, and networking on social media may also help to disseminate knowledge in cardio-oncology in general.

Table 2.

Tweets disseminating the survey in English and Spanish nationally and internationally

The Oncology Perspective

There are about 12 million cancer patients and over 15 million cancer survivors, and 1 of 3 adults have cardiovascular disease (nearly 82 million patients). Approximately 30% patients receiving cancer therapy will have cardiovascular (CV) complications. Some of these CV complications may not become apparent until more than 10 years after completion of multidisciplinary treatments (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy). There are numerous additional concerns for oncologists managing cancer treatment in patients with CV disease: these patients may not be able to tolerate the appropriate therapy, and this may adversely affect their survival. On the other hand, many of the patients that are treated with potentially cardiotoxic therapy are at risk for the development of CV disease. These examples illustrate why the need for cardio-oncology collaboration is of utmost importance and has made a huge impact in improving the care of our patients. The goal of a multidisciplinary cardio-oncology team (both in the academic and the community setting) is threefold. First, it is important to identify short-term and delayed cardiotoxic effects of cancer treatments. Second, it is important to develop strategies for screening and monitoring of cancer patients for CV toxicity before, during, and after cancer treatment. Lastly, it is imperative to outline a multidisciplinary approach to managing cardio-oncology patients using current recommendations to optimize survivorship outcomes. The goal of the cardio-oncology network is to educate the cardiologists and oncologists in our communities and improve the care of patients who have both cancer and heart disease.

Cardio-oncology, even though initially developed with the leadership of oncology, has really grown in strength and numbers as a result of the leadership of cardiologists. Engaging the oncology community has been and continues to be a priority through advocacy, collaborative research, and education, as well as through cancer survivorship research and clinics. From an advocacy perspective, national leadership groups including the American Heart Association (AHA), the ACC, and the International Cardio-Oncology Society have included both cardiologists and oncologists on their executive committees, in an effort to bridge collaborations between oncology and cardiology. The journals Cardio-Oncology and JACC Cardio-Oncology have both cardiologists and oncologists on their editorial boards. National oncology guidelines now also include cardio-oncology guidelines. Both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn.org) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have cardio-oncology guidelines outlining monitoring and prevention across the spectrum of cancer care [11]. Large oncology meetings such as the ASCO and the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) have also had education sessions specifically dedicated to cardio-oncology. In order to continue oncology patients on curative therapies or life-extending therapies while minimizing the burden of toxicity, close collaboration between oncology and cardiology needs to continue across the spectrum of prevention, treatment, and survivorship.

Cancer survivors, even when cured from their cancer, do not have the same life expectancy as individuals not diagnosed with cancer. Increased mortality occurs as a result of disease recurrence, but the occurrence of cardiovascular disease and second malignancies continues to have an enormous impact on cancer survivors [3, 12•, 13]. As a result, cardio-oncology and cardiovascular disease risk assessment need to be addressed not only during treatment but also throughout the survivorship period through multidisciplinary approaches not only with cardiology but also physical medicine and rehabilitation and physical therapy [14]. Additionally, as many patients are living for years with their cancer, understanding the impact of cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy is vital not only for oncologists but also primary care providers. As a result, educational tools continue to be developed (Cancer.net through ASCO, Cardiosmart through ACC) to educate patients and providers. Incorporating cardio-oncology into medical education across nursing, graduate school, and medical school will also enhance the workforce in better understanding the complex issues related to cardiovascular disease in cancer survivors.

The Academic Perspective: The Case for Academic Advocacy

Academic centers have played a critical role in the advocacy for the discipline of cardio-oncology. They are uniquely placed to do so for numerous reasons.

The multidisciplinary concept and nature of academic centers generate both the need and opportunity for exchange on multiple levels. Being typically composed of highly specialized providers with expert knowledge in their respective areas, these centers see the need for collaboration, consultation, and referral. Oncologists and hematologists, for instance, may rather refer patients to cardiologists than trying to treat them on their own. This is driven by the volume of their practice as well as the vast increase in knowledge and constant inflow of new data and information that does not allow to be an expert in every field any longer. Even within each subspecialty, these dynamics call for further specialization to maintain fluency and up-to-date expertise. This move towards sub-specialization is nurtured at academic centers, and new developments are naturally embraced and supported as it was in the beginning of the field of cardio-oncology.

The academic mindset also lends itself to the recognition of trends and discoveries as the ones made in the intersection of cardiology and oncology/hematology. Academic centers often have the opportunity for cross-talk between clinicians, clinician scientists, and basic scientists for a broad portfolio of research activities that engage more than one group. The common involvement in pharmaceutical studies at various phases of drug development furthermore allows for exposure to (new) side effects and their assessment and adjudication, such as cardiovascular toxicities in oncology and hematology trials, including phase 1 trials where cardiac safety is a major endpoint. These engagements enable interaction and advocacy on the level of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as well as funding agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In addition, research activities lend themselves to publications and presentations at professional society meetings to the point of the introduction of subsections, even dedicated journals for cardio-oncology sessions at major cardiology, oncology, and hematology meetings. Activities in this area have led to the formation of specific cardio-oncology chapters or councils at leading professional societies like the ACC, the AHA, and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), as well as the formation of international and national cardio-oncology societies, which provide additional opportunities for interaction, collaboration, and advancement for the field of cardio-oncology.

With a large enough volume of patients undergoing cross-disciplinary studies and care and the necessary infrastructure and institutional support, academic centers were also the first to conceptualize and operationalize cardio-oncology clinics. This has linked to advocacy on the level of clinical practice well beyond internal confines to include government and nongovernment payors, policy advisors, and patient groups. The clinical practice organization and experience moreover have provided a connection with practitioners at non-academic institutions. Academic centers often serve as tertiary referral centers and point of contact and resource.

The connection with non-academic practices has been enhanced by the ability of academic centers to organize educational courses in cardio-oncology. Academic centers are also in a unique position to allow for exposure and training in the area of cardio-oncology including advocacy for cardio-oncology education in resident and fellow educational curricula. This very aspect naturally lends itself to educational interactions across institutions and efforts of standardization. These efforts extend to patient practice in general and the pursuit of practice guidelines.

Thus, in summary, academic centers by their mandate and resources for research, education, and the advancement of clinical practice have been critical in outlining, developing, and advancing the field of cardio-oncology and play a critical role in advocacy by full engagement in all these described activities.

Across the Ocean: Europe—The UK in Cardio-Oncology

Cardio-oncology in the UK is a rapidly developing field. With a growing appreciation of the multitude of cardiotoxicities, especially with newer cancer treatments, the UK’s first cardio-oncology clinic was set up at the Royal Brompton Hospital by Dr Alexander Lyon and Dr Stuart Rosen [15]. This was soon followed by a collaborative effort from oncologists and cardiologists across the country to form the UK Cardio-Oncology Consortium in 2012 which demonstrated the early buy-in achieved among many oncologists. This body expanded and founded the British Cardio-Oncology Society (BOCS) in 2014 to promote research and clinical excellence in this new field and to advocate for cancer patients with cardiac issues [16]. Further growth in the field led to the appointment of the UK’s first consultant cardiologist specifically in cardio-oncology, Dr Arjun K Ghosh [17•]. His joint appointment at Europe’s largest cardiac center (Barts Heart Centre) [18] and Europe’s projected largest cancer center (University College London Hospital) [19] emphasized the collaborative and cross-disciplinary nature of cardio-oncology in the UK.

The BCOS partnered with the International Cardio-Oncology Society to host the Global Cardio-Oncology Summit (GCOS) at the Royal College of Physicians in London in 2017 to educate participants from 31 countries on all aspects of cardio-oncology. Additionally, the University College London Cancer Academy Cardio-Oncology Course is a national cardio-oncology course now in its third year [20]. The nature of this course is very multidisciplinary with significant participation from hematologist-oncologists, oncologists, trainees, specialist nurses, cardiac physiologists, pharmacists, and primary care doctors.

Several hospitals in the UK now have established cardio-oncology fellowship programs for the UK and international trainees, and as such, the future of cardio-oncology in the UK looks bright. Table 3 summarizes the leading cardio-oncology programs and scientific societies in the UK.

Table 3.

Leading programs and professional societies in cardio-oncology in the UK

| Organization | Activity | Website/contact info |

|---|---|---|

| University College London Hospital (UCLH) Cancer Academy | Organized the first national cardio-oncology symposium in the UK led by Dr Arjun K Ghosh and Dr Andrew Wilson |

https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/our-services/find-service/cancer-services/cancer-academy |

| British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) | Ensured that cardio-oncology was included in the new UK cardiology training curriculum | https://www.britishcardiovascularsociety.org/ |

| Has become a co-organizer of the UCLH Cancer Academy Cardio-Oncology symposium along with the British Cardio-Oncology Society. | https://www.bcs.com/education/BCOS-Cardio-Oncology.asp | |

| British Cardio-Oncology Society (BCOS) |

Along with the British Society of Echocardiography has produced the UK’s first cardio-oncology guidelines (in press) BCOS members have published widely in the field including international cardio-oncology guidelines The BCOS website hosts details of UK Cardio-Oncology Clinical and Research Fellowship opportunities |

http://bc-os.org/ |

| BCOS members are in a number of leadership positions in the European Society of Cardiology Cardio-Oncology Council | https://www.escardio.org/Councils/council-of-cardio-oncology | |

| BCOS is the UK representative of the International Cardio-Oncology Society | https://members.ic-os.org/ |

UCLH, University College London Hospital; UK, United Kingdom; BCOS, British Cardio-Oncology Society

Across the Ocean: Europe—Poland for Central/Eastern Europe in Cardio-Oncology

The bases for nationwide cooperation between cardiologists and oncologists in Poland began in 2009, when the national consultant in cardiology (Prof. Grzegorz Opolski) and the national consultant in clinical oncology (Prof. Maciej Krzakowski) established a working group to develop standards of cardio-oncology care in breast cancer [21•]. Dr. Sebastian Szmit was appointed executive editor. The Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education (CMKP) is a unique medical academic institution in Poland, working under auspices of the Ministry of Health, and is responsible for postgraduate education for all physicians. The cardio-oncology didactic curriculum includes “Oncology in Cardiology,” obligatory course within specialty program in cardiology, and “Basics of Cardio-Oncology,” obligatory lectures during specialty program in internal medicine and clinical oncology.

Poland has a characteristic organization of oncology care based on an oncology hospital’s network. The first oncology center in Poland was established on May 29, 1932, based on an initiative by Maria Skłodowska–Curie, the double Nobel Prize laureate, who donated a gram of radium, used as the basis for starting the Radium Institute, currently the main oncology center in Poland: the Maria Skłodowska–Curie National Research Institute of Oncology in Warsaw. Subsequently every major Polish city built an independent oncology center. The Polish National Oncology Network designed a common algorithm of multidisciplinary management, including cardio-oncology, for all Polish hospitals treating cancer patients, now approved by the National Council of Oncology at the Polish Ministry of Health. Therefore, cardio-oncology services are now staffed with more than 50 cardiologists employed in oncology centers, cooperating closely with university-based cardiology departments. An expert group for cardio-oncology was established: the group organized three Polish cardio-oncology congresses and cardio-oncology sessions during each annual congress of the Polish Cardiac Society and published their research findings, some of them in cooperation with the Polish Lymphoma Research Group [22–29]. In 2012, Dr. Adam Torbicki and Dr. Sebastian Szmit started the ICOS-East European Branch, and in 2019, the ICOS-Poland Chapter was established. Polish cardiologists participated in the 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity, This document was published in the European Heart Journal and the Polish Heart Journal [30]. Table 4 summarizes the current cardio-oncology structure in Poland.

Table 4.

Cardio-oncology in Poland

| Subject | Main characteristic | Activities for cardio-oncology |

|---|---|---|

| Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education | The central medical academic institution responsible for the preparation of programs and conducting and coordinating postgraduate medical education in Poland. |

“Oncology in Cardiology”—obligatory courses within the specialty program in cardiology Basics of Cardio-Oncology”—obligatory lectures during introductory courses in internal medicine and clinical oncology |

| Polish Cardiac Society (Polskie Towarzystwo Kardiologiczne, PTK) |

Part of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Polish members automatically become members of the ESC ESC guidelines are implemented in everyday clinical practice in Poland |

The 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity translated into Polish on the Polish Heart Journal after publication in the European Heart Journal Polish cardiologists are part of the ESC Council of Cardio-Oncology |

| Polish Lymphoma Research Group (PLRG) |

Thematic sections dedicated to specific clinical problems in lymphomas Each section meets semi-annually to discuss the achievements and define new purposes The cardio-oncology section meets regularly since 2011 |

Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity Early use of echocardiography in high risk DLBCL during R-CHOP / R-COMP chemotherapy Cardiovascular safety of pixantrone Cardiotoxicity of first and second generation BTK inhibitors |

| Polish National Oncology Network |

19 hospitals with oncology service Support of Polish Lung Cancer Group (PLCG) |

Since 2016 three annual nationwide Polish cardio-oncology congresses and 2 sessions during congresses of Polish Cardiac Society have been organized Ongoing program: Cardiology baseline assessment and evaluation during anticancer treatment in five selected types of cancer disease (1) breast cancer, (2) lung cancer, (3) ovarian cancer, (4) colorectal cancer, (5) prostate cancer |

ESC, European Society of Cardiology; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R-CHOP, rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, Oncovin (vincristine), prednisone; R-COMP, rituximab-cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, Myocet, prednisone; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase

Cardio-Oncology in Latin America

Cardio-oncology is rapidly growing in Latin America. However, there are some national differences mainly related to resources availability and disparities between different countries. Overall, there are few cardio-oncologists across LA, mainly confined to academic centers, while community doctors are typically not involved in cardio-oncology care. Patients’ access to cardio-oncology care is dependent upon the referral by the oncologists, and in some countries, the lack of interest by the cancer teams and oncology services results in the absence of and limited development of cardio-oncology practice and services. While some countries like Cuba and Guatemala are just getting started with their first steps on cardio-oncology, others like Brazil and Argentina started its implementation a decade ago and now have reached a large expansion and dissemination of the field. As a result, Brazil and Argentina can count on a better distribution of cardio-oncology units across their territories and have the support of strong national societies in cardiology and oncology with cardio-oncology committees and strong presence in the international community, having recently hosted international scientific sessions. Many Brazilian and Argentinean cardio-oncologists have an active role in international cardio-oncology professional organizations like ICOS and have had very productive scientific output with publications in major cardiovascular, oncology, and cardio-oncology journals and participation in their editorial boards. The implementation of cardio-oncology chapters in Latin American countries and the creation of dedicated multidisciplinary associations, like the Asociacion de Cardio-Oncologia de la Republica Argentina (ACORA) and the Cardio-Oncology Institute of University of Sao Paulo (Brazil), have greatly contributed to the interest in this field, yet some countries still lack this cardio-oncology structure and professional organizations. Other countries in Latin America like Mexico and Costa Rica have also developed cardio-oncology programs and currently have ICOS Chapters.

Overall, Latin America has an urgent need for awareness, promotion, education, and access to care in cardio-oncology (both by cardiologists and oncologists) to meet current guidelines and recommendations. Therefore, further involvement of medical professional societies to provide support and facilitate education and expansion of cardio-oncology services in Latin American countries is essential in order to achieve this goal (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cardio-oncology in Latin America

| Local dedicated CO society/association |

CO section on local cardiology/oncology societies | ICOS national chapter | Local fellowship/ trainning program | Host international CO meting | Participation in editorial board of major CO jorunal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Yes (website under construction) |

Yes https://www.portal.cardiol.br/estaduais-depart-e-grupo-estudo |

Yes |

Yes https://www.fm.usp.br/ccex/complementacao-especializada/cardio-oncologia |

Yes |

Yes |

| Argentina |

Yes |

Yes (No link provided) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Cuba | No information available | |||||

| Chile | No | No | No | No |

Yes (No link provided) |

No |

| Guatemala | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Colombia | No information available | |||||

| Mexico | No information available | Yes | No | No | ||

| Costa Rica | No |

Yes |

Yes |

No | No | No |

CO, cardio-oncology; ICOS, International Cardio-Oncology Society

Advocacy, Policy, and Economics in Cardio-Oncology

Rising demands and costs to healthcare delivery remain universal issues among nations, and the percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) devoted to healthcare continues to rise [31]. The recent pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has added tremendously to that concern [32], further straining healthcare budgets and putting great stress on the economics of both developed and emerging nations [33].

Patients with cardiovascular disease and cancer are among the groups at high risk or poor outcomes of COVID-19 and are at the highest risk of severe illness and mortality. Advocacy in this area has been addressed in an ICOS consensus statement on cardio-oncology care in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic recently published [34•].

As cancer and heart disease are responsible for the majority of deaths in the world, collaborative advocacy efforts in this area should expand. This involves a number of vital stakeholders (Table 6) [35] with the goal of raising awareness and support so that cardio-oncology care can become more widely available and that both patients and physicians have the resources they need for successful outcomes.

Table 6.

Advocacy issues/concerns and potential proposed solutions/strategies

| Stakeholder | Issues/concerns | Proposed solutions/strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Legislators | Healthcare policy and legislation come from specific committees in the US House and Senate. Advocates provide insight into the specialty and advocate for specific bills or policy issues such as limiting preauthorization and onerous documentation | Building relationships and articulating patient needs are critical and take an ongoing effort. Meeting legislators in DC as well as in district is critical to building these relationships. Local, state, and federal representatives should be engaged to educate them on the challenges of practitioners and patients alike |

| Researchers | Oncologic drug development needs specific measurements of cardiovascular toxicity included in adverse events protocols | FDA has accepted this need and has held meetings with cardio-oncology stakeholders to address the scope of cardiotoxicity |

| Physicians in training | Increased graduate medical education positions and help with education costs for the looming shortage of cardio-oncologists |

While universal across all specialty programs, cardio-oncology is a new field that needs to be championed. In the USA, delineation of these fellowship programs is ongoing |

| Practitioners | Relieving administrative burden, preauthorization requirements, appropriate reimbursement, and prescription drug costs have been a concern with cancer and heart disease consuming a great deal of the healthcare resources | Partnering with other specialty groups is important to speak with a unified voice. Constant changes in federal and state regulations, patient privacy rights, and practitioner burnout all impact delivery of care |

| Survivorship groups | Ongoing efforts to address unique patient issues with need for awareness on late presentation/long-term cardiovascular effects of certain cancer treatments | Cancer and cardiovascular professional associations have developed programs for patients to learn the delayed effects of cancer treatment, particularly in survivors of cancer experienced during childhood |

| Payors | New technologies require specific codes and values for reimbursement. Work with the American Medical Association RUC Committee and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services (CMS) aims to ensure cardio-oncology representation with education for payors about what cardio-oncology is and how it impacts patients care | Taxonomy codes specific for cardio-oncology and reimbursement for consultative services and procedures such as MRI or strain echocardiography have been successful. The cost of prescription drugs and drug shortages are advocacy issues that need constant reminders for payors to be properly addressed |

US, United States; DC, District of Columbia; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; RUC, Relative Value Scale Update Committee; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Cardio-oncology advocacy has also been directed towards informing and educating those stakeholders who control healthcare budgets and may impact resources available for patient care. (Table 6).

Conclusions

Cardio-Oncology has grown significantly in the last decade. The growth of cardio-oncology has differed in many countries and geographic areas. Even though there are outstanding large academic centers and cardio-oncologists leading the this growth, the awareness and knowledge of cardio-oncology among the practicing medical community caring for a large segment of the population are still limited, and this may limit the positive impact of cardio-oncology on the overall population healthcare outcomes. The development of collaborative educational, advocacy, and research networks may be instrumental to improve this situation.

To achieve this goal there is need for:

(1.) Oncologists “buy-in”: More cooperation between cardiologists and oncologists at the local, state, and national level by engaging via existing professional societies and by personal engagement at each institution with organization of combined clinical and educational activities.

(2.) Education: Increase active involvement of newcomers to the field in the large number of existing educational opportunities including conferences, webinars, and publications currently available through professional organizations like the ACC, ASCO, AHA, ESC, ICOS, and others to help guide and sustain the growth.

(3.) Increase the number of cardio-oncology programs in the community: By having physicians involved in the first two steps equipped with the knowledge and thrive to lead a program, becoming a “champion” to engage leadership in both cardiology and oncology in their institutions to financially support and provide structure and resources for these programs.

(4.) Research: The research databases at each institution provide an opportunity for newly established programs to collaborate with others, participate in the larger cardio-oncology community, and provide data that improves patient care and also provides information for administrators to support and sustain these programs.

(5.) Advocacy: The participation in professional organization committees providing opportunity for the interaction with other stakeholders like insurance payors, governmental agencies, healthcare regulators, and others will allow to improve cardio-oncology care and decrease gaps in access to care.

Declarations

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

Diego Sadler, Anita Arnold, Joerg Herrmann, Andres Daniele, Carolina Maria Pinto Domingues Carvalho Silva, Arjun K. Ghosh, Roohi Ismail-Khan, Luis Raez, Anne Blaes, and Sherry-Ann Brown declare no conflict of interest. Sebastian Szmit has received clinical trial funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer for the CARAVAGGIO trial and the API-CAT study; has received compensation from Clinigen Group for participation on a multinational European Union advisory board; and has received compensation for service as a consultant from Amgen, Angelini, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Roche, and TEVA.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardio-oncology

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrmann J. From trends to transformation: where cardio-oncology is to make a difference. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3898–3900. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturgeon KN, Deng L, Bluethman SL, et al. A population based study of cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US cancer patients. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3889–3897. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25:1029–1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fradley MG, Brown AC, Shields B, et al. Developing a comprehensive cardio-oncology program at a cancer institute: the Moffitt experience. Oncol Rev. 2017;11:340. doi: 10.4081/oncol.2017.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barac A, Murtagh G, Douglas P, et al. Health of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. JACC. 2015;65:2739. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.• Sadler D, Chaugalian C, Cubeddu R, Stone E, Samuel T, et al. Practical and cost effective model to build and sustain a cardio-oncology program. Cardio Oncol J. 10.1186/s40959-020-00063-xThis study describes how to set up and sustain a program utilizing existing institutional resources without additional investment. Describes the key 4 components for a program.

- 8.Sadler D, Fradley M, Ismail Khan R, Raez L, Bhandare D, Elson L, Perloff D, et al. Florida Inter-Specialty Collaborative Project to improve cardio oncology awareness and identify existing gaps. JACC Cardio Onc. 2020;2(3):535–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadler D, Arnold A, Ismail-Khan R, Fradley M, Guerrero P et al. FCACC and FLASCO Cardio Oncology Online Educational platform. 2020 https://accfl.org/Cardio-Oncology

- 10.• Sadler D, De Cara J, Herrmann J, Arnold A, Ghosh A, Abdel-Quadir H, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on cardio oncology: results from the COVID-19 International Collaborative Network Survey. Cardio Oncol. 2020. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-88776/v1This is the first collaborative project completed by the Cardio-Oncology Collaborative Network and a result of an international cooperation between cardiologists and oncologists. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Armenian S, Lacchetti C, Barac A, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):893–891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.• Blaes A, Konety S. Cardiovascular disease in breast cancer survivors: an important topic in breast cancer survivorship. JNCI. 2020. 10.1093/jnci/djaa097This editorial highlights the increased cardiovascular mortality among breast cancer survivors compared to cancer-free women, particularly in elderly patients and in those with estrogen receptor-positive status and reviews other cohorts and risk factors in this population.

- 13.Bradshaw PT, Stevens J, Khankari N, Teitelbaum SL, Neugut AI, Gammon MD. Cardiovascular disease mortality among breast cancer survivors. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):6–13. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilchrist S, Barac A, Ades P, et al. On behalf of the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention Committee. Circulation. 2019;139:e997–e1012. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pareek N, Cevallos J, Moliner P, Shah M, Tan LL, Chambers V, Baksi AJ, Khattar RS, Sharma R, Rosen SD, Lyon AR. Activity and outcomes of a cardio-oncology service in the United Kingdom—a five-year experience. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(12):1721–1731. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1292.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardio-Oncology in the United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/council-of-cardio-oncology/cardio-oncology-in-the-united-kingdom. Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 17.Ghosh AK, Manisty C, Woldman S, Crake T, Westwood M, Walker JM. Setting up cardio-oncology services. Br J Cardiol. 2017;24(1):1. doi: 10.5837/bjc.2017.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor J. Barts Heart Centre is on track to become the largest cardiovascular centre in Europe. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2968–2969. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A new clinical facility - proton beam therapy, blood disorders and surgery. Available at: https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/aboutus/NewDev/NCF/Pages/Home.aspx. Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 20.British Cardiovascular Society. Available at: https://www.bcs.com/education/BCOS-Cardio-Oncology.asp. Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 21.Opolski G, Krzakowski M, Szmit S, Banach J, Chudzik M, Cygankiewicz I, Drożdż J, Filipiak KJ, Grabowski M, Kaczmarek K, Kochman J, Lewek J, Maciejewski M, Miśkiewicz Z, Niwińska A, Pieńkowski T, Piestrzeniewicz K, Sinkiewicz W, Wranicz JK, Zawilska K, Task Force of National Consultants in Cardiology and Clinical Oncology Recommendations of National Team of Cardiologic and Oncologic Supervision on cardiologic safety of patients with breast cancer. The prevention and treatment of cardiovascular complications in breast cancer. The Task Force of National Consultants in Cardiology and Clinical Oncology for the elaboration of recommendations of cardiologic proceeding with patients with breast cancer. Kardiol Pol. 2011;69(5):520–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaborowska-Szmit M, Krzakowski M, Kowalski DM, Szmit S. Cardiovascular complications of systemic therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1268. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szmit S, Grela-Wojewoda A, Talerczyk M, Kufel-Grabowska J, Streb J, Smok-Kalwat J, Iżycki D, Chmielowska E, Wilk M, Sosnowska-Pasiarska B. Predictors of new-onset heart failure and overall survival in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with liposomal doxorubicin. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75614-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Styczkiewicz K, Styczkiewicz M, Mędrek S, Jankowski P, Szmit S, Stec S. Telecardio-onco AID: a new concept for a coordinated care program in breast cancer (BREAST-AID): rationale and study protocol. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2019;129(4):295–229. doi: 10.20452/pamw.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jurczak W, Szmit S, Sobociński M, Machaczka M, Drozd-Sokołowska J, Joks M, Dzietczenia J, Wróbel T, Kumiega B, Zaucha JM, Knopińska-Posłuszny W, Spychałowicz W, Prochwicz A, Drohomirecka A, Skotnicki AB. Premature cardiovascular mortality in lymphoma patients treated with (R)-CHOP regimen - a national multicenter study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(6):5212–5217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szmit S, Jurczak W, Zaucha JM, Drozd-Sokołowska J, Spychałowicz W, Joks M, Długosz-Danecka M, Torbicki A. Pre-existing arterial hypertension as a risk factor for early left ventricular systolic dysfunction following (R)-CHOP chemotherapy in patients with lymphoma. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(11):791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szmit S, Jurczak W, Zaucha JM, Długosz-Danecka M, Sosnowska-Pasiarska B, Chmielowska E, Joks M, Drozd-Sokołowska J, Knopińska-Posłuszny W, Spychałowicz W, Kumiega B, Charliński G, Morawska M, Słomian G. Acute decompensated heart failure as a reason of premature chemotherapy discontinuation may be independent of a lifetime doxorubicin dose in lymphoma patients with cardiovascular disorders. Int J Cardiol. 2017;235:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Długosz-Danecka M, Gruszka AM, Szmit S, Olszanecka A, Ogórka T, Sobociński M, Jaroszyński A, Krawczyk K, Skotnicki AB, Jurczak W. Primary cardioprotection reduces mrtality in lymphoma patients with increased risk of anthracycline cardiotoxicity, treated by R-CHOP regimen. Chemotherapy. 2018;63(4):238–245. doi: 10.1159/000492942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jurczak W, Długosz-Danecka M, Szmit S. Cardio-oncology for better lymphoma therapy outcomes. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(4):e273–e275. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Muñoz DR, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, Habib G, Lenihan DJ, Lip GY, Lyon AR, Fernandez TL, Mohty D, Piepoli MF, Tamargo J, Torbicki A, Suter TM. 2016 ESC Position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. Kardiol Pol. 2016;74(11):1193–1233. doi: 10.5603/KP.2016.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Accessed 10/25/2020: https://www.statista.com/statistics/268826/health-expenditure-as-gdp-percentage-in-oecd-countries

- 32.Business of Medicine | Taking Care of Patients’ Hearts During Cancer Treatment: Collaborative Oncology and Cardiovascular Care https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/10/01/01/42/taking-care-of-patients-hearts-during-cancer-treatment-collaborative-oncology-and-cv-care Accessed 10/25/2020

- 33.Accessed 10/25/2020:https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world

- 34.Lenihan D, Carver J, Herrmann J, et al. Cardio-oncology care in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. An International Cardio-Oncology Society statement. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(6):480–504. doi: 10.3322/caac.21635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sklar DP. Why effective healthcare advocacy is so important today. Acad Med. 2016;91:1325–1328. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]