Abstract

Gastrodin (GAS), the main phenolic glycoside derivative from Gastrodiaelata Blume, has several bio-activities. However, the molecular mechanisms of these protective actions currently remain unclear. This study aimed to investigate the mechanisms of GAS on lead (Pb)-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in the kidneys and primary kidney mesangial cells. Results indicated that GAS improved Pb-induced renal dysfunction and morphological changes in mice. GAS ameliorated Pb-induced inflammation in kidneys by reducing the TNF-α and IL-6 levels. GAS inhibited Pb-induced oxidative stress by regulating the glutathione, thioredoxin (Trx), and Nrf2 antioxidant systems. Furthermore, GAS supplementation increased the activation of SOD, GPx, HO-1, and NQO1 in the kidneys. GAS decreased the expression levels of HMGB1, TLR4, RAGE, MyD88, and NF-κB. These results were further confirmed in primary kidney mesangial cells. Collectively, this study demonstrated that GAS alleviated Pb-induced kidney oxidative stress and inflammation by regulating the antioxidant systems and the Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Highlights

Gastrodin ameliorated Pb-induced kidney injury in mice.

Gastrodin inhibited oxidative stress and inflammation in kidneys.

Gastrodin activated the GSH, Trx and Nrf2 antioxidant system in kidneys.

Gastrodin inhibited the activities of HMGB1. RAGE, TLR4, and MyD88

Keywords: gastrodin, lead, renal inflammation, oxidative stress, HMGB1, Nrf2

Introduction

Lead (Pb) is considered to be a major environmental pollutant and occupational health hazard worldwide, It can be obtained from Pb paint, as well as air, soil, drinking water, and food [1–3]. Pb is selectively accumulated in the kidneys, which is the main target of Pb toxicity. Pb causes proximal tubular dysfunction and kidney failure [4, 5]. HMGB1, a highly conserved nuclear protein, is passively secreted by necrotic cells or activated released from immunocompetent cells, which can trigger a lethal inflammatory process by binding with its receptors, including RAGE and TLR4 [6–7]. Pb exposure causes inflammation and apoptosis through the HMGB1 pathway [1, 8, 9]. Pb exposure in drinking water causes memory impairments and inflammation via the TLR4/MyD88 pathway [3, 10]. Pb exposure could inhibit the Nrf2 singling pathway, further decreasing the expression levels of various antioxidative genes, such as HO-1 and NQO1 [11, 12]. Pb exposure also causes oxidative stress by inhibiting the glutathione (GSH) and thioredoxin (Trx) antioxidant systems [4, 13].

Gastrodin (GAS) is the main phenolic glycoside extracted from the traditional Chinese herb “Tian ma” (Gastrodia elata Blume), which has multiple pharmacological effects, including anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidative properties [14–16]. Our previous study and others have indicated that 400 mg/kg GAS orally does not have side effects on animals [17, 18]. Moreover, GAS could alleviate oxidative stress, inflammation, and lipid metabolism in HL-7702 cells and animals [15]. GAS ameliorated striatal inflammation and oxidative stress in rats by inhibiting the HMGB1/NF-kB pathway [16]. GAS ameliorates myocardial damage by inhibiting inflammation [17]. GAS supplementation exerts a protective effect on liver inflammation by inhibiting the TLR4 pathway [19]. GAS treatment inhibits oxidative stress and inflammation in brain, lung, and liver by activating the Nrf2 pathway [20–22]. However, whether GAS can improve Pb-induced renal damage remains unknown.

In the current work, we aimed to determine the nephroprotective effect of GAS on Pb-induced oxidative and inflammation and to clarify the roles of the GSH, Trx, and Nrf2 antioxidant systems and the HMGB1 pathway in the protective action of GAS.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

GAS (≥98%) and lead acetate (≥99%) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 (≥99%) was obtained from Abmole Bioscience Inc. (Houston, USA). HMGB1, RAGE, TLR4, MyD88, Trx, TrxR, NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, and β-actin antibodies kindly provided by Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Animals and ethics

ICR mice (50 males; 20 ± 1 g) were supplied by Beijing HFK Bioscience Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). All experimental procedures were approved by Jiangsu Normal University Committees (No. IACUC-20.1.15) and complied with the Chinese directives and guidelines for the care of laboratory animals.

Experimental design

Animals were maintained on a constant 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum for 1 week and then divided into five groups (10 mice/group) as follows:(1) Normal control group, (2) Pb group, (3) Pb + GAS (50 mg/kg b.w.) group, (4) Pb + GAS (100 mg/kg b.w.) group, and (5) GAS (100 mg/kg b.w.). In group (1), mice were provided with distilled water as the only drinking water. In groups (2), (3), and (4), the procedure of Pb inducing renal injury was performed as described previously [3, 5], with Pb acetate (250 mg Pb/L) add to in the drinking water of mice. In groups (3) and (4), mice were also supplied with GAS (50 or 100 mg/kg b.w.) intragastrically once daily. In group (5), mice were provided with distilled water as the only drinking water and supplied with GAS 100 mg/kg b.w., intragastrically once daily. Based on previous studies, the dose of GAS, selected herein was sufficient to exert a nephroprotective effect [16–18].

Three months later, mice were sacrificed by decapitation. Blood and kidneys were collected immediately and stored for future experiments.

Biochemical analysis

The concentrations of creatinine, urea, and uric acid in serum, as well as the activities of SOD, GSH, and GPx in kidneys, were measured with commercial kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China) [3].

Histological evaluations

Pathological changes of kidneys were observed with commercial kits reagents [3, 22]. In a typical procedure, kidney tissue were fixed using 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for preparation, and 5 μm-thick sections were cut. Sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin according to standard protocols (Nanjing Jiancheng, China). A total of 100 intersections were examined for each sample. Kidney damage was divided into six levels.

Cell culture and treatment

Primary kidney mesangial cells were isolated and cultured by the methods described previously [5]. The cells were incubated with Pb (50 μM), Pb(50 μM) + GAS (100 μg/mL), Pb(50 μM) + GAS (100 μg/mL) for 24 h at 37°C, with 0 μM Pb samples serving as the control group [5, 8]. The Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 (2 μM) was administrated for 1 h in advance, Then, The cells were harvested for subsequent experiments [23].

Western blot analysis

The expression levels of HMGB1, RAGE, TLR4, MyD88, Trx, TrxR, NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, and β-actin in kidneys were analyzed by western blot according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio/Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.42 software (NIH Bethesda, MD, USA) [10, 24].

Statistical analysis

The samples satisfied normality assumption, and statistical significant differences between means were evaluated by Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

Results

GAS rescued Pb-induced renal dysfunction

We found that Pb exposure increased the serum concentration of creatinine, urea, and uric acid compared with those in the controls by 146.6%, 78.4%, and 124.1%, respectively. However, GAS supplementation significantly improved renal function, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

GAS rescued Pb-induced renal dysfunction of mice

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | Urea (mg/dl) | Uric acid (mg/dl) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.03 ± 0.13 | 34.85 ± 1.24 | 1.12 ± 0.15 |

| Pb | 2.54 ± 0.16## | 62.18 ± 2.18## | 2.51 ± 0.24## |

| Pb + GAS (50 mg/kg) | 2.12 ± 0.23** | 48.24 ± 1.41** | 2.12 ± 0.15** |

| Pb + GAS (100 mg/kg) | 1.43 ± 0.17** | 42.18 ± 1.35** | 1.56 ± 0.12** |

| GAS (100 mg/kg) | 1.02 ± 0.16** | 33.24 ± 1.17** | 1.11 ± 0.13** |

One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons of multiple group means followed by post hoc testing. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 7). ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group.

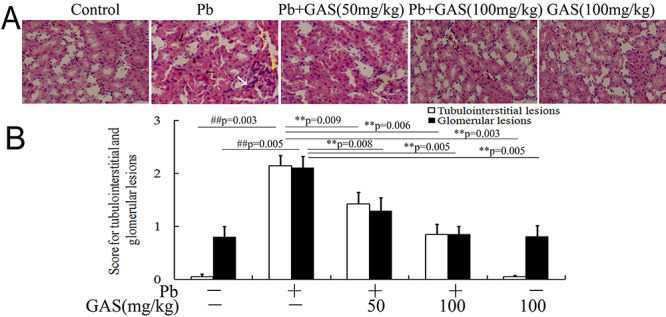

GAS improved histological alterations in kidneys

Histopathological studies on kidney tissues were performed. As shown in Figure 1, Pb exposure caused obvious histological alterations such as renal tubular epithelial-cell denaturation, cell swelling, vacuolar degeneration, necrosis, Bowman capsule distortions, and chronic focal inflammation. The score for glomerular and tubulointerstitial lesions remarkably increased after Pb exposure. However, GAS supplementation remarkably reduced these histological damages in kidneys.

Figure 1 .

GAS improved histological alterations in the kidneys of the Pb group. (A) Representative histological images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in kidney sections (×200). (B) The score for tubulointerstitial and glomerular lesions. The white arrow indicates infiltrating leukocytes. The black arrow indicates renal tubular epithelial cell denaturation, cell swelling, vacuolar degeneration, and necrosis. The yellow arrow indicates Bowman capsule distortions. All values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group.

GAS inhibited Pb-induced oxidative stress in kidneys

As shown in Table 2, the group treated with Pb showed a significant increase of 44.3% in MDA level compared with the control whereas the MDA content decreased following GAS supplementation. Compared with the control, Pb exposure induced a significant decrease in the levels of GSH, SOD, and GPx by 47.9%, 35.5%, and 23.1%, respectively, which were partly reversed by GAS supplementation.

Table 2.

GAS inhibited Pb-induced oxidative stress in the kidneys of mice

| MDA (nM/mg prot) | SOD (U/mg prot) | GSH (U/mg prot) | GPx (U/mg prot) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 314.26 ± 12.71 | 232.64 ± 21.62 | 131.43 ± 23.18 | 112.82 ± 14.23 |

| Pb | 453.52 ± 21.07## | 150.18 ± 28.32## | 68.53 ± 12.32## | 86.73 ± 14.16## |

| Pb + GAS (50 mg/kg) | 426.18 ± 15.34** | 198.38 ± 15.26** | 88.42 ± 12.23** | 96.24 ± 21.04** |

| Pb + GAS (100 mg/kg) | 370.82 ± 21.03** | 225.17 ± 23.12** | 121.85 ± 13.86** | 108.72 ± 13.21** |

| GAS (100 mg/kg) | 312.37 ± 11.62** | 234.67 ± 20.43** | 132.63 ± 14.64** | 113.06 ± 12.59** |

One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons of multiple group means followed by post hoc testing. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 7). ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group.

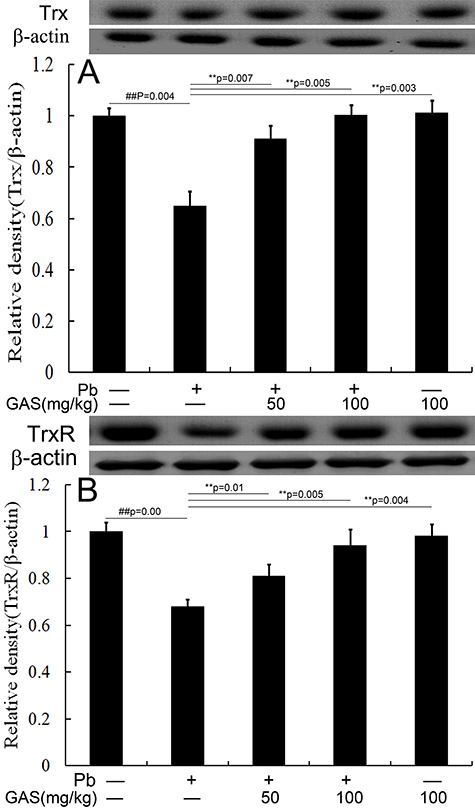

GAS activated the Trx pathway in kidneys

The Trx antioxidant pathway was strongly correlated to kidney oxidative stress and inflammation after Pb exposure. We further detected the expression levels of TrxR and Trx. Results demonstrated that the expression levels of TrxR and Trx were significantly reduced in kidneys of the Pb group compared with those of the normal control (Fig. 2). Interestingly, GAS reversed this effect (P < 0.05).

Figure 2 .

GAS activated the Trx pathway in the kidneys of mice. (A) Relative density analysis of the Trx protein bands. (B) Relative density analysis of the TrxR protein bands. β-actin was probed as an internal control in relative density analysis. The vehicle control is set as 1.0. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and representative of at least three independent experiments (individual animals). All values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group.

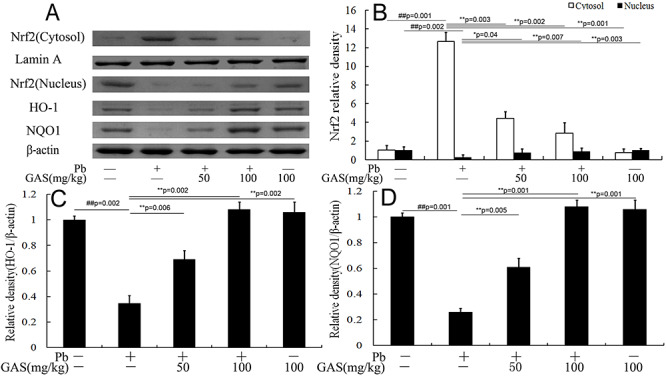

GAS activated the Nrf2 pathway in kidneys

The Nrf2 antioxidant pathway is involved in defending against oxidative stress and inflammation. As presented in Figure 3, the levels of HO-1, NQO1, and nucleus Nrf2 in kidneys considerably decreased in mice exposed to Pb compared with those in the normal control. Interestingly, GAS supplementation reversed this effect (P < 0.05).

Figure 3 .

GAS activated the Nrf2-ARE pathway in the kidneys of mice. (A) Western blot analysis of the NF-κB p65, TNF-α and IL-6 proteins in the kidneys. (B) Relative density analysis of the Nrf2 protein bands. (C) Relative density analysis of the HO-1 protein bands. (D) Relative density analysis of the NQO1 protein bands. β-actin was probed as an internal control in relative density analysis. The vehicle control is set as 1.0. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and representative of at least three independent experiments (individual animals). All values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group.

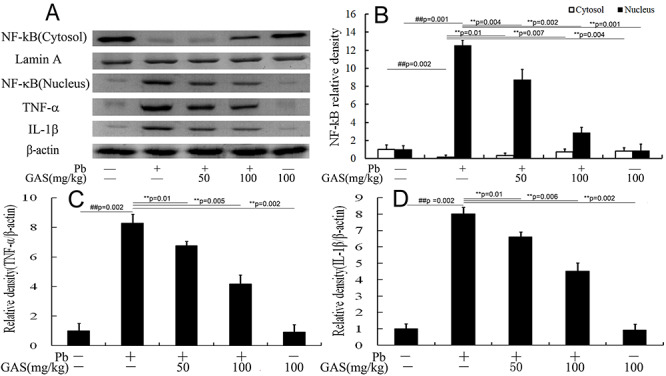

GAS suppressed Pb-induced inflammation in kidneys

To further determine whether GAS could inhibit inflammatory response in kidneys, we evaluated the levels of NF-κB, TNF-α, and IL-1β. Data showed that Pb exposure increased the activities of TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-κB in kidneys compared with those of the normal control group. However, the levels of the inflammatory cytokines tremendously decreased after GAS supplementation (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 .

GAS inhibited Pb-induced inflammation in the kidneys of mice. (A) Western blot analysis of the NF-κB p65, TNF-α and IL-6 proteins in the kidneys. (B) Relative density analysis of the NF-κB p65 bands. (C) Relative density analysis of the TNF-α protein bands. (D) Relative density analysis of the IL-6 protein bands. β-actin and Lamin A were probed as the internal control in relative density analysis. The vehicle control is set as 1.0. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and representative of at least three independent experiments (individual animals). All values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group.

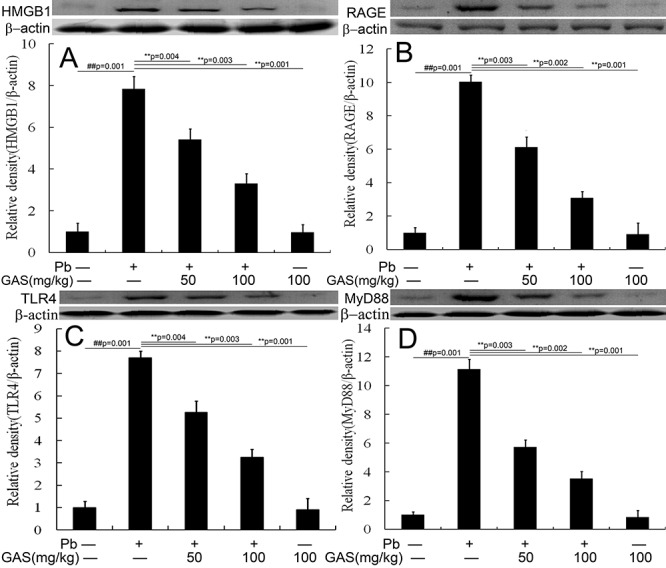

GAS inhibited the HMGB1 signaling pathway in kidneys

The HMGB1 pathway was correlated with renal inflammation [18]. As illustrated in Figure 4, Pb treatment upregulated the levels of HMGB1, RAGE, TLR4, and MyD88 in kidneys compared with those of the normal control. However, GAS supplementation reduced the levels of these proteins (P < 0.05).

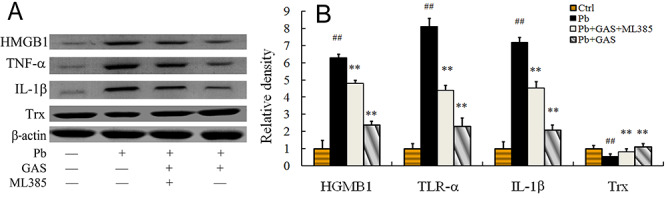

GAS suppressed Pb-induced inflammation in primary kidney mesangial cells

To confirm the roles of Nrf2 pathway on Pb-induced inflammation in primary kidney mesangial cells, the inhibitor of Nrf2 was used in this study. As depicted in Figure 5, Pb exposure upregulated the levels of HMGB1, TNF-α, and IL-1β and downregulated the level of Trx in primary kidney mesangial cells compared with those of the normal control. However, NEO application decreased the expression levels of HMGB1, TNF-α, and IL-1β in Pb-induced primary kidney mesangial cells and this repressive effect was abolished by treatment with the Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 (Fig. 6).

Figure 5 .

GAS inhibited the HMGB1 pathway in the kidneys of mice. (A) Relative density analysis of the HMGB1 protein bands. (B) Relative density analysis of the RAGE protein bands. (C) Relative density analysis of the TLR4 protein bands. (D) Relative density analysis of the MyD88 protein bands. β-actin was probed as an internal control in relative density analysis. The vehicle control is set as 1.0. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and representative of at least three independent experiments (individual animals). All values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group.

Figure 6 .

The expression levels of the TNF-α, IL-1β, Trx and HGMB1 in kidney mesangial cells. (A) Western blot analysis of the TNF-α, IL-1β, Trx, and HGMB1 proteins. (B) Relative density analysis of the TNF-α, IL-1β, Trx, and HGMB1 protein bands. β-actin was probed as an internal control in relative density analysis. The vehicle control is set as 1.0. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and representative of at least three independent experiments. All values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. ##P < 0.05, compared with the control group; **P < 0.05, vs. Pb-treated group. GAS: Gastrodin; Pb: lead; ML385: The Nrf2 inhibitor ML385.

Discussion

Pb is one of the most ubiquitous and unavoidable environmental toxicants that can induce kidney injury [5, 25]. Meanwhile, GAS supplementation adjusts the GSH, Trx, and Nrf2 antioxidant system and the HMGB1 pathway in kidneys. Pb exposure induces multiple renal injuries [5, 12, 26]. In the present study, Pb resulted in renal dysfunction (Table 1) and histological injury (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the oral administration of GAS improved the Pb-induced kidney injury in mice, suggesting that GAS had a renoprotective property.

Oxidative stress plays a key role in renal inflammation [11, 12, 26]. The GSH and Trx antioxidant systems are two major thiol-dependent antioxidant systems. The GSH antioxidant system is involved in the defense against oxidative stress through the efficient removal of various ROS by GPx. Disulfide reductase activity can participate in the defense against oxidative stress through the Trx antioxidant system [27]. Pb exposure could cause kidney inflammation by stimulating oxidative stress [11, 12, 26]. Our data demonstrated that Pb exposure decreased the activities of GSH, GPx, and SOD in kidneys, suggesting that Pb caused oxidative stress by inhibiting the GSH antioxidant system [11, 12]. Pb exposure has caused oxidative stress-mediated cardiac injury in rats by increasing the activities of the antioxidant enzymes TrxR and SOD [28]. Pb exposure also reportedly stimulates oxidative stress in rat kidneys by decreasing the activities of TrxR, SOD, and GPx [12]. Pb exposure further provokes oxidative stress in nerve cells by inhibiting the GSH and Trx antioxidant systems [29]. GAS supplementation could attenuate 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells by increasing the levels of GSH and Trx [30]. Similarly, we found that GAS treatment led to decreased MDA content along with increased activities of GPx, SOD, GSH, Trx, and TrxR in kidneys of the Pb group (Table 2). This finding suggested that GAS supplementation inhibited Pb-induced kidney damage by activating the GSH and Trx antioxidant systems (Fig. 2).

Nrf2 is a key regulator of antioxidant proteins, which control the driven genes of antioxidant response element (ARE) [20, 21, 31]. Oxidative stress can cause the nucleus translocation of Nrf2. Then, Nrf2 binds to ARE and upregulates the expression of antioxidant genes and the transcription of genes, such as Trx and TrxR [31, 32]. Activated Nrf2 can attenuate oxidative stress mediated damage through the Trx signaling pathway [31–33]. Pb exposure could lead to kidney oxidative stress and inflammation by suppressing the Nrf2 pathway [11, 12]. GAS supplementation reportedly exerts anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects on alcohol-induced liver injury of mice through the Nrf2 pathway [19]. GAS treatment further ameliorates oxidative stress and inflammation in SH-SY5Y cells by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway [30, 34]. GAS supplementation inhibits LPS-induced lung injury through the suppression of inflammatory cytokines and the activation of Nrf2 [21]. Our data showed that GAS supplementation attenuated Pb-induced oxidative stress and increased the levels of HO-1, NQO1, and Nrf2 nuclear translocation, highlighting that GAS was a potent agonist of Nrf2 (Fig. 3). All these findings indicated that GAS inhibited Pb-induced kidney damage via the Nrf2 antioxidant system.

Pb exposure could cause renal dysfunction by stimulating inflammatory response in vivo and in vitro [11, 22, 25]. Previous research has suggested that GAS plays a protective role against the inflammatory injury of brain tissue in animals by regulating NF-κB pathway [16, 35]. GAS ameliorates bile duct ligation-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in rats [36]. Our experimental data also revealed the inhibitory effect of GAS on the expression levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in kidney tissues of Pb-treated mice (Fig. 4). Thus, GAS may inhibit the inflammatory response of liver tissue by inhibiting the release of inflammatory factors to alleviate kidney injury in Pb-treated mice.

HMGB1 could regulate renal inflammation through interactions with multiple cell-surface receptors, such as RAGE and TLRs [7, 18, 37]. Trx overexpression could inhibit the activation of HMGB and inflammasomes in bronchial epithelial cells and rat lung [38]. Previous research has indicated that Pb exposure increases the HMGB1 level in rat hippocampus and PC12 cells [8]. Pb could increase the RAGE level in the cerebrospinal fluid and hippocampus of rats [9]. Our previous study has revealed that Pb induces cognitive impairments and inflammatory response through the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway [3]. Pretreatment with GAS prevents human retinal endothelial-cell apoptosis triggered by high glucose via the TLR4 pathway [39]. GAS supplementation exerts a distinct anti-inflammatory activity in livers by inhibiting the TLR4 pathway [19]. The results of this study indicated that the expression levels of HGMB1, RAGE, TLR4, and MyD88 significantly increased, and that GAS could inhibit these proteins’ expression in kidneys (Fig. 5). Thus, GAS may exert a protective effect on Pb-induced injury by suppressing the HGMB1 pathway.

To verify whether the Nrf2 pathway is associated with the anti-inflammatory effect of GAS on kidney exposed to Pb, we also detected the expression levels of HMGB1, TNF-α, IL-1β, and Trx in primary kidney mesangial cells (Fig. 6). We found that the key protein of Trx pathway were upregulated after GAS application in Pb-exposed kidney mesangial cells and this promotive effect was reversed by treatment with the Nrf2 inhibitor ML385. Moreover, the key proteins of inflammatory pathway including HMGB1, TNF-α, and IL-1β were significantly downregulated after GAS treatment in Pb-induced kidney mesangial cells and this repressive effect was abolished by treatment with the Nrf2 inhibitor ML385. These results in vitro further confirmed that GAS improved Pb-induced inflammation through the Nrf2 signaling pathways.

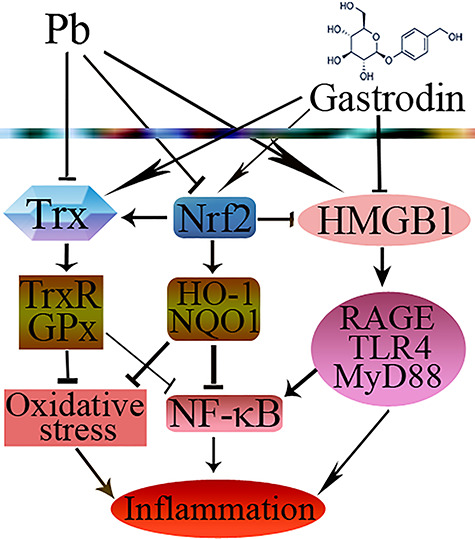

In conclusion, GAS supplementation can significantly alleviate Pb-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in kidney via the GSH, Trx, and Nrf2 antioxidant systems and the HMGB1 pathway (Fig. 7). The renoprotective action of GAS warrants further research.

Figure 7 .

Schematic diagram showed the possible protective effects of GAS in Pb-induced kidney injury. The → indicates activation or induction, and  indicates inhibition or blockade.

indicates inhibition or blockade.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31972942), the Graduate Student Scientific Research Innovation Projects of Jiangsu Education Department (SJKY19-2064), and the Graduate Student Scientific Research Innovation Projects of Jiangsu Normal University (2020XKT481).

Contributor Information

Zhi-Kai Tian, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, No. 101, Shanghai Road, Tongshan New Area, Xuzhou, Jiangsu 221116, P. R. China.

Yu-Jia Zhang, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, No. 101, Shanghai Road, Tongshan New Area, Xuzhou, Jiangsu 221116, P. R. China.

Zhao-Jun Feng, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, No. 101, Shanghai Road, Tongshan New Area, Xuzhou, Jiangsu 221116, P. R. China.

Hong Jiang, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, No. 101, Shanghai Road, Tongshan New Area, Xuzhou, Jiangsu 221116, P. R. China.

Chao Cheng, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, No. 101, Shanghai Road, Tongshan New Area, Xuzhou, Jiangsu 221116, P. R. China.

Jian-Mei Sun, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, No. 101, Shanghai Road, Tongshan New Area, Xuzhou, Jiangsu 221116, P. R. China.

Chan-Min Liu, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, No. 101, Shanghai Road, Tongshan New Area, Xuzhou, Jiangsu 221116, P. R. China.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1. Banijamali M, Rabbani-Chadegani A, Shahhoseini M. Lithium attenuates lead induced toxicity on mouse non-adherent bone marrow cells. Trace Elem Med Biol 2016;36:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mabrouk A, Bel Hadj Salah I, Chaieb W, Ben Cheikh H. Protective effect of thymoquinone against lead-induced hepatic toxicity in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2016;23:12206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu CM, Yang W, Ma JQet al. Dihydromyricetin inhibits lead-induced cognitive impairments and inflammation by the adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase pathway in mice. J Agric Food Chem 2018;66:7975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conterato GMM, Quatrin A, Somacal Set al. Acute exposure to low lead levels and its implications on the activity and expression of cytosolic thioredoxin reductase in the kidney. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2014;114:476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu CM, Yang HX, Ma JQet al. Role of AMPK pathway in lead-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in kidney and in paeonol-induced protection in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2018;122:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. González-Guerrero C, Cannata-Ortiz P, Guerri Cet al. TLR4-mediated inflammation is a key pathogenic event leading to kidney damage and fibrosis in cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Arch Toxicol 2017;91:1925–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paudel YN, Angelopoulou E, Piperi Cet al. Enlightening the role of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in inflammation: updates on receptor signaling. Eur J Pharmacol 2019;858:172487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang M, Li Y, Wang Yet al. The effects of lead exposure on the expression of HMGB1 and HO-1 in rats and PC12 cells. Toxicol Lett 2018;288:111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen X, Xia L, Liu Let al. Altered clearance of beta-amyloid from the cerebrospinal fluid following subchronic lead exposure in rats: roles of RAGE and LRP1 in the choroid. Trace Elem Med Biol 2020;61:126520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang W, Tian ZK, Yang HXet al. Fisetin improves lead-induced neuroinflammation, apoptosis and synaptic dysfunction in mice associated with the AMPK/SIRT1 and autophagy pathway. Food Chem Toxicol 2019;134:110824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Albarakati AJA, Baty RS, Aljoudi AMet al. Luteolin protects against lead acetate-induced nephrotoxicity through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways. Mol Biol Rep 2020;47:2591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. AL-Megrin WA, Soliman D, Kassab RBet al. Coenzyme Q10 activates the antioxidant machinery and inhibits the inflammatory and apoptotic cascades against lead acetate-induced renal injury in rats. Front Physiol 2020;11:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conterato GMM, Augusti PR, Somacal Set al. Effect of lead acetate on cytosolic thioredoxin reductase activity and oxidative stress parameters in rat kidneys. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2007;101:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matias M, Silvestre S, Falcã A, Alves G. Gastrodiaelata and epilepsy: rationale and therapeutic potential. Phytomedicine 2016;23:1511–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qu LL, Yu B, Li Zet al. Gastrodin ameliorates oxidative stress and proinflammatory response in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway. Phytother Res 2016;30:402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Long H, Ruan J, Zhang Met al. Gastrodin alleviates Tourette syndrome via Nrf-2/HO-1/HMGB1/NF-kB pathway. Biochem Mol Toxicol 2019;33:e22389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li F, Wang X, Lou C. Gastrodin pretreatment impact on sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport ATPase (SERCA) and calcium phosphate (PLB) expression in rats with myocardial ischemia reperfusion. Med Sci Monit 2016;22:3309–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma JQ, Sun YZ, Ming QLet al. Effects of gastrodin against carbon tetrachloride induced kidney inflammation and fibrosis in mice associated with the AMPK/Nrf2/HMGB1 pathway. Food Funct 2020;11:4615–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li XX, Jiang ZH, Zhou Bet al. Hepatoprotective effect of gastrodin against alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Physiol Biochem 2019;75:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peng Z, Wang S, Chen Get al. Gastrodin alleviates cerebral ischemic damage in mice by improving anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation activities and inhibiting apoptosis pathway. Neurochem Res 2015;40:661–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang Z, Zhou J, Song Det al. Gastrodin protects against LPS-induced acute lung injury by activating Nrf2 signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2017;8:32147–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma JQ, Liu CM, Yang W. Protective effect of rutin against carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in mouse kidney associated with the ceramide, MAPKs, p 53 and calpain activities. Chem Biol Interact 2018;286:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lu C, Fan G, Wang D. Akebia saponin D ameliorated kidney injury and exerted anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects in diabetic nephropathy by activation of NRF2/HO-1 and inhibition of NF-KB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2020;80:106467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ma JQ, Sun YZ, Ming QLet al. Paeonol attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced mouse liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell activation associated with the SIRT1/TGF-β1/Smad3 and autophagy pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2019;77:105984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang T, Chen S, Chen Let al. Chlorogenic acid ameliorates lead-induced renal damage in mice. Biol Trace Elem Res 2019;189:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ranaa MN, Tangponga J, Rahman MA. Xanthones protects lead-induced chronic kidney disease (CKD) via activating Nrf-2 and modulating NF-κB, MAPK pathway. Biochem Biophys Rep 2020;21:100718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu J, Holmgren A. The trioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med 2014;66:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davuljigari CB, Gottipolu RR. Late-life cardiac injury in rats following early life exposure to lead: reversal effect of nutrient metal mixture. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2020;20:249–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu C, Pan S, Dong M, Niu Y. Astragaloside IV attenuates lead acetate-induced inhibition of neurite outgrowth through activation of Akt-dependent Nrf2 pathway in vitro. BBA-Mol Basis Dis 1863;2017:1195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Q, Niu C, Zhang X, Dong M. Gastrodin and isorhynchophylline synergistically inhibit MPP+-induced oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells by targeting ERK1/2 and GSK-3β pathways: involvement of Nrf2 nuclear translocation. ACS Chem Nerosci 2018;9:482–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhu Z, Wang Y, Liang Det al. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate suppresses pulmonary fibroblast proliferation and activation induced by silica: role of the Nrf2/Trx pathway. Toxicol Res 2016;5:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim YC, Yamaguchi Y, Kondo Net al. Thioredoxin-dependent redox regulation of the antioxidant responsive element (ARE) in electrophile response. Oncogene 2003;22:1860–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma Q, He X. Molecular basis of electrophilic and oxidative defense: promises and perils of Nrf2. Pharmacol Rev 2012;64:1055–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oliveira MR, Brasil FB, Fürstenau CR. Nrf2 mediates the anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects induced by gastrodin in hydrogen peroxide-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Mol Neurosci 2019;69:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ye T, Meng X, Zhai Yet al. Gastrodin ameliorates cognitive dysfunction in diabetes rat model via the suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front Pharmacol 2016;9:1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao S, Li N, Zhen Yet al. Protective effect of gastrodin on bile duct ligation-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2015;86:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen Q, Guan X, Zuo Xet al. The role of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in the pathogenesis of kidney diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B 2016;6:183–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peeters PM, Eurlings IMJ, Perkins TNet al. Silica-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in vitro and in rat lungs. Part Fibre Toxicol 2014;11:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang TH, Huang CM, Gao Xet al. Gastrodin inhibits high glucose-induced human retinal endothelial cell apoptosis by regulating the SIRT1/TLR4/NF-κBp65 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep 2018;17:7774–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]