Abstract

Cisplatin is used for treating multiple types of cancers. Alongside its therapeutic effects, there are side effects, including cytotoxicity and genotoxicity for healthy cells, which are mainly related to radical oxygen species (ROS) production by the drug. These side effects could troublesome the treatment process. Previous studies have suggested that members of Pinaceae family are rich sources of antioxidant components. This article investigates the antioxidant activity (AA) of Pinus eldarica (Pinaceae) along with its cyto/genoprotective effects following cisplatin exposure on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) cell line. Pinus eldarica’s hydroalcoholic bark extract (PEHABE) and P. eldarica’s needle volatile oil (PENVO) were prepared using maceration and hydrodistillation methods, respectively. PENVO was analysed via gas chromatograph–mass spectrometry, and the total phenolic content of PEHBAE was measured by folin–ciocalteu reagent. AA of both PEHABE and PENVO were determined using DPPH assay. Moreover, MTT test was used to determine the cytoprotective effects of both agents. Comet and micronucleus (MN) tests were also performed to investigate the genoprotective effect of P. eldarica. Germacrene D (35.72%) was the main component of PENVO. PEHABE showed higher AA compared with PENVO, with the highest AA observed at 25 and 250 μg/ml, respectively. Both PENVO and PEHABE were cytoprotective, with the latter having mitogenic effects on cells at 75, 100, and 200 μg/ml concentrations (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001). Also, both PEHABE and PENVO showed genoprotective effects against cisplatin in comet assay (P < 0.001). As PEHABE’s concentrations were increased, a reduced number of MN formation was observed after cisplatin’s exposure (P < 0.001). In conclusion, PEHABE had higher AA compared with PENVO, and both agents had cyto/genoprotective effects on HUVECs.

Keywords: cisplatin, Pinus eldarica, DPPH, MTT, comet, micronucleus

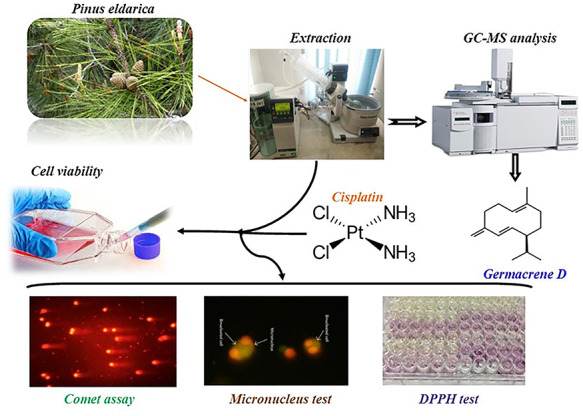

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

In 2018, there was an estimate of 18.1 million new cases and 9.6 million deaths of cancer worldwide [1]. Platinum-based anti-tumor medicines like cisplatin have shown potential for managing various types of cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, lung, ovarian, breast, and brain cancers. However, there have been reports of major side effects of cisplatin, including nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, GI toxicity, hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, hematological toxicity, and neurotoxicity. Production of radical oxygen species (ROS) by cisplatin has been the major suspect of these side effects [2]. It has also been stated that the cytotoxicity effects of cisplatin may be due to the DNA damage caused by this medicine [3, 4]. Cytotoxicity caused by cisplatin can be induced via interaction with DNA transcription and/or replication. Cisplatin can also damage malignant cells through cellular apoptosis, which is stimulated by various signal transduction pathways. Neither cytotoxicity nor apoptosis are tumor-specific; hence, normal and healthy cells may be affected equally. Moreover, side effects, such as neuro and/or renal toxicity or bone marrow suppression, may emerge during the treatment with cisplatin [5]. This drug reacts with several targets in cells, such as proteins and glutathione molecules. A small percentage of the platinum complex of cisplatin that would eventually reach DNA would cause genotoxicity [6].

Studies indicated that dietary phenolic compounds (e.g. flavonoids, phenolic acid, quinones, etc.) have shown promising antioxidant activity (AA) via in vitro experiments compared to vitamin C or vitamin E [7, 8]. Pinaceae family are the most spread conifers in the world. Pines in the Pinaceae family can withstand extreme environmental conditions, such as nutrient-poor and acidic soils, low water stress, moisture, and temperature [9]. Pinus eldarica, also known as the Elder pine, Tehran pine, Quetta pine, and eldarica pine, is a rare member of the Pinaceae family that is endemic to Iran. Tehran Pine is also cultivated in 17 other countries all over the world from south-east Australia to northern parts of Italy and the south-west part of the USA [10, 11]. Previous investigations of the Pinaceae family have suggested promising antioxidant capacity of this family [12, 13], with P. eldarica’s bark being a rich source of polyphenolic compounds [14]. Moreover, there have been reports of P. eldarica’s antibacterial, antihyperlipidemic, and antioxidant effects [15–17]. A study indicates that the bark extracts of Pinus maritime, another member of Pinaceae, have similar polyphenolic profile compared to P. eldarica [14]. Pinus maritime’s bark extract, known as Pycnogenol®, has shown genoprotective effects in human lymphocytes against H2O2 via reduced chromosome breakage [18]. Also, it has been suggested that Pycnogenol® is able to decrease H2O2-induced DNA damage on HeLa cell line, with a dose-dependent manner [19]. Our goal in this study was to elaborate whether P. eldarica is able to protect a normal cell line from cisplatin’s side effects, including cytotoxicity and genotoxicity, rather than a cancerous cell line. Since cisplatin may induce its cytotoxic and genotoxic effects through production of ROS, the genoprotective effects of P. eldarica and its antioxidant capacity following cisplatin exposure on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were investigated.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

Needle leaves and barks of P. eldarica were collected from Isfahan, Iran, in July 2019 under the authority of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Plant was then acknowledged by the Department of Pharmacognosy’s experts at the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, and a reference specimen from the samples (No. 3318) was stored.

Preparation of volatile oil

Leaves were cut into small pieces, and 100 g of them were distributed in 1 l of distilled water. To obtain P. eldarica’s needle volatile oil (PENVO), needle leaves were distilled in a Clevenger-type apparatus for 4 h. Volatile oil was then separated from the watery phase and it was stored in a sealed vial. To ensure no degradation would occur, PENVO was kept inside a refrigerator at 4°C for further experiments [20].

Preparation of hydroalcoholic bark extract

Powdered barks (20 g) were macerated with methanol–water (70:30) and shaken for 30 min. The mixture was then kept for 24 h in a dark room. On the next day, the obtained mix was shaken for another 30 min. Mixture was then filtered and freeze-dried to obtain a concentrated dry extract. Pinus eldarica’s hydroalcoholic bark extract (PEHABE) was kept in a refrigerator at 4°C for further experiments [21].

Volatile oil analysis

PENVO was analysed using Agilent technologies 7890A gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (GC–MS) device coupled with 5975C mass detector via following settings: 0.1 μl of PENVO was injected to the device. Helium carrier gas flow rate was set at 1.9 ml/min with 17.7 lbf/in2 pressure. Injection site’s temperature was set at 280°C and the column’s temperature was set to rise at 4°C per minute, with its initial temperature being 60°C till the column reaches 280°C. HP-5 MS was used as capillary column (30 × 0.25 mm; film thickness 0.25 μM). Mass spectra’s ionized potential was set at 70 eV. Also, ionizing source temperature was set at 230°C and ionization current was 750 μA [20]. MSD ChemStation was used as the operating software.

The retention time of n-alkanes (C9-C20) was obtained under the same conditions to calculate the Kovats index of each component. Constituents of PENVO were identified by comparing their Kovats index to those reported by Adams [22]. Also, computer matched components with its database (NIST and Wiley 275 l). Mass spectra’s fragmentation patterns were also compared to other sources [23].

Phenolic content measurement

Folin-Ciocalteu (F-C) reagent (Merck, Germany) was used to determine the total phenolic profile (TPC) of PEBHAE [24]. Gallic acid (GA) was used as a standard to draw the calibration curve. In order to prepare 0.5% (w/v) stock solution of GA, 0.5 g of GA powder was dissolved in ethanol–water (10:90), and different concentrations (50, 100, 150, 250, and 500 mg/l) were prepared from the stock solution. Twenty microliters of different samples, i.e. GA as standard, PEBHAE, and water as blank were mixed with 1.58 ml distilled water separately, and 100 μl F-C reagent was added. After 8 min, 300 μl of sodium bicarbonate was added to the mixture. Absorbance of the mentioned concentrations of standard, sample, and blank solutions were therefore determined at 765 nm wavelength via UV-visible spectrophotometer (Bio Tek, PowerWave XS, USA). Using the calibration curve drawn by different concentrations of GA, TPC of PEBHAE was determined. Results were expressed as mg of GA equivalents to each gram of PEBHAE’s dried weight (mg GAE/g).

Antioxidant capacity

A 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DDPH, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) assay conducted by Brand-Williams et al. was used [25] with some modifications to measure the antioxidant capacity of PENVO and PEBHAE. Briefly, 100 μl of samples were mixed with equal volume of DPPH (dissolved in methanol) in a 96-microwell plate and the mixture was left alone for 30 min in a dark place. Using ELISA Reader (Bio Tek Instruments, Inc, 140213C, USA), absorbance of the plate was determined at 517 nm. GA and a mixture of methanol and water were used as the positive control and the blank solution, respectively [26]. Using the provided formula, AA of each sample was calculated.

|

Cell culture

HUVECs cell line was obtained from the Iranian Biological Resource Center, Iran. Cells were cultured in a medium of high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Bio-Idea, Iran) along with 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Bio-Idea), 100 IU/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. Also, cells were kept in 25-cm2 and 75-cm2 flasks and were incubated at 37°C with <5% carbon dioxide and 95% humidified atmosphere [16, 27]. To harvest the cells, flask containing them was first washed with sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS, Bio-Idea). Then, trypsin was added. After 3 min, cell culture medium was added to neutralize trypsin. Next, cells were centrifuged at a velocity of 1800 rpm for 5 min to gain pellets of cells in order to carry out further investigations [27–29]. These procedures were followed for storing cells and for also investigating both cytotoxicity and genotoxicity tests performed in this study.

Measurement of cells’ viability

3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) assay introduced by Mosmann [30] was performed with minor modifications to determine the cytotoxicity of PENVO, PEBHAE, and cisplatin in HUVECs. Different concentrations of PEBHAE (10–200 μg/ml), PENVO (0.01–0.2 μg/ml), and cisplatin (0.5–160 μM) were provided. First, a total of cells ( cells/ml) were incubated for 24 h in a 96-well plate. Next, cells were treated with different concentrations of PEBHAE, PENVO, and cisplatin separately and were then incubated for 48 h. After this period, the medium was emptied and the cells were incubated with the MTT reagent for 4 h. Next, DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well to dissolve formazan crystals. Finally, using an ELISA reader, each well’s absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Cell’s medium was used as blank, and untreated cells were marked as negative control (NC) [31]. To determine the cytoprotective effect of PEBHAE and PENVO over cisplatin, cells were first exposed to cisplatin 15 μM. After 1 h, the medium was washed away and desired concentrations of PEBHAE and PENVO were added.

cells/ml) were incubated for 24 h in a 96-well plate. Next, cells were treated with different concentrations of PEBHAE, PENVO, and cisplatin separately and were then incubated for 48 h. After this period, the medium was emptied and the cells were incubated with the MTT reagent for 4 h. Next, DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well to dissolve formazan crystals. Finally, using an ELISA reader, each well’s absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Cell’s medium was used as blank, and untreated cells were marked as negative control (NC) [31]. To determine the cytoprotective effect of PEBHAE and PENVO over cisplatin, cells were first exposed to cisplatin 15 μM. After 1 h, the medium was washed away and desired concentrations of PEBHAE and PENVO were added.

Comet assay

To perform this test, an established method was used with some modifications [32]. Slides were coated with normal melting agarose (NMA, Cinnagen, Iran) 1% and were left to dry for 24 h at room temperature. A total of  cells/ml were provided in a 6-well cell culture plate. Cells were first seeded inside the plate for 24 h. Then, concentrations of interest were added for a 24-h period. Next, cells were trypsinized and 300 μl of cell suspension was well mixed with 400 μl of low melting point agarose (LMA, Sigma-Aldrich), 1%. Next, 200 μl of the mixture was poured on the slides covered by coverslips and the slides were then kept at 4°C for 10 min. After that, coverslips were removed and lysis buffer (NaCl: 146.1 g, EDTA: 37.2 g, Tris: 1.2 g, NaOH: 8 g, and Triton: 10.7 g) was poured on the slides for 40 min at 4°C. Then, the slides were washed with deionized water and they were placed inside the electrophoresis tank filled with tank buffer (NaOH: 10 M, EDTA: 200 mM, pH ~ 13). Tank’s outer environment was covered with ice to keep a low temperature inside the tank. Horizontal electrophoresis was performed afterward for 40 min with voltage and amperage set at 25 V and 100 mA, respectively. Next, the slides were removed and submerged into neutralizing buffer (Tris: 48.5 g, pH ~ 7.5) for 10 min. Slides were stained using ethidium bromide for 5 min and then washed with deionized water. Stained slides were observed with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), with excitation and barrier filters set at 515 and 590 nm, respectively. DNA damage was determined using free analysis software (CometScore v2.0.0.38) [33]. Tail length, percent of DNA in tail, and tail moment were used to determine the genotoxicity [34]. To investigate the genoprotection effects of PEBHAE and PENVO, same steps as discussed were taken. First, genoprotective agent was incubated with cells for 24 h. Next, medium was washed with PBS and then genotoxic agent (cisplatin) was added to the cells medium for another 24 h.

cells/ml were provided in a 6-well cell culture plate. Cells were first seeded inside the plate for 24 h. Then, concentrations of interest were added for a 24-h period. Next, cells were trypsinized and 300 μl of cell suspension was well mixed with 400 μl of low melting point agarose (LMA, Sigma-Aldrich), 1%. Next, 200 μl of the mixture was poured on the slides covered by coverslips and the slides were then kept at 4°C for 10 min. After that, coverslips were removed and lysis buffer (NaCl: 146.1 g, EDTA: 37.2 g, Tris: 1.2 g, NaOH: 8 g, and Triton: 10.7 g) was poured on the slides for 40 min at 4°C. Then, the slides were washed with deionized water and they were placed inside the electrophoresis tank filled with tank buffer (NaOH: 10 M, EDTA: 200 mM, pH ~ 13). Tank’s outer environment was covered with ice to keep a low temperature inside the tank. Horizontal electrophoresis was performed afterward for 40 min with voltage and amperage set at 25 V and 100 mA, respectively. Next, the slides were removed and submerged into neutralizing buffer (Tris: 48.5 g, pH ~ 7.5) for 10 min. Slides were stained using ethidium bromide for 5 min and then washed with deionized water. Stained slides were observed with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), with excitation and barrier filters set at 515 and 590 nm, respectively. DNA damage was determined using free analysis software (CometScore v2.0.0.38) [33]. Tail length, percent of DNA in tail, and tail moment were used to determine the genotoxicity [34]. To investigate the genoprotection effects of PEBHAE and PENVO, same steps as discussed were taken. First, genoprotective agent was incubated with cells for 24 h. Next, medium was washed with PBS and then genotoxic agent (cisplatin) was added to the cells medium for another 24 h.

Micronucleus assay

This test was done using the guideline provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (No. 487, published 2016) [35]. A suspension of cells ( ) was prepared and was transferred to a 12-well cell culture plate. After cells were attached to wells for 24 h, the plate was rinsed with sterile PBS. Next, positive control group received 10 μM of cisplatin, and NC received cell culture medium, and therapeutic groups received different concentrations of PEBHAE (10–200 μg/ml) along with cisplatin. Cells were then incubated for 24 h with added agents. For the case of the therapeutic groups, cells were first incubated with the protective agent (PEBHAE) for 24 h, and after a rinsing step with PBS, genotoxic agent (cisplatin with a concentration of 10 μM) was added to the plate for a 24-h period of incubation. After concentrations of interest were incubated with different groups, 4 μg/ml of cytochalasin B (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cells and the plate was incubated for 28 h. Next, each well was rinsed with PBS, and trypsinized cells were immersed in hypotonic potassium chloride (0.075 M) for 45 min at 37°C. Then, cold methanol–acetic acid (3:1) solution was added to the cells as the fixator. Next, the cells were stained using sodium fluorescein and ethidium bromide, respectively. Finally, the slides were observed under a fluorescence microscope at 495 nm.

) was prepared and was transferred to a 12-well cell culture plate. After cells were attached to wells for 24 h, the plate was rinsed with sterile PBS. Next, positive control group received 10 μM of cisplatin, and NC received cell culture medium, and therapeutic groups received different concentrations of PEBHAE (10–200 μg/ml) along with cisplatin. Cells were then incubated for 24 h with added agents. For the case of the therapeutic groups, cells were first incubated with the protective agent (PEBHAE) for 24 h, and after a rinsing step with PBS, genotoxic agent (cisplatin with a concentration of 10 μM) was added to the plate for a 24-h period of incubation. After concentrations of interest were incubated with different groups, 4 μg/ml of cytochalasin B (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cells and the plate was incubated for 28 h. Next, each well was rinsed with PBS, and trypsinized cells were immersed in hypotonic potassium chloride (0.075 M) for 45 min at 37°C. Then, cold methanol–acetic acid (3:1) solution was added to the cells as the fixator. Next, the cells were stained using sodium fluorescein and ethidium bromide, respectively. Finally, the slides were observed under a fluorescence microscope at 495 nm.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the data was obtained using a one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA) along with Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test via Graph Pad Prism 8 (Graph Pad Software, Inc, CA, USA). Values of P ≤ 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

Volatile oil and extract yields

A total of 3765 g fresh leaves of P. eldarica were collected, which yielded 1.5 ml of volatile oil accounting for a total of 0.04% (v/w) as the concentration for PENVO. By measuring the volatile oil’s weight and by dividing it by its volume, the density of volatile oil was determined to be 0.87 mg/ml. The bark of P. eldarica yielded 22% of hydroalcoholic extract.

Volatile oil’s constituent analysis by GC–MS

PENVO was obtained through hydrodistillation with a yield of 0.1%. More than 20 compounds were identified, amounting for 92.84% of the total volatile oil. Table 1 shows each constituent with its percentage in the sample analysed by GC–MS. As the results indicate, 31% of PENVO consists of monoterpenoids and the rest of the sample includes sesquiterpenoids. Germacrene D (35.72%) has the highest percentage among other components. Other major constituents of PENVO are β-caryophyllene (18.45%) and δ-cadinene (5.53%), respectively.

Table 1.

Pinus eldarica’s leaf volatile oil composition

| No | Component | Type | KIa base | KI | TICb% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-Pinene | Monoterpene | 939 | 939 | 3.21 |

| 2 | β-Pinene | Monoterpene | 980 | 979 | 1.21 |

| 3 | 3-Carene | Monoterpene | 1011 | 1012 | 1.02 |

| 4 | Limonene | Monoterpene | 1031 | 1032 | 1.8 |

| 5 | trans-β-Ocimene | Monoterpene | 1050 | 1051 | 0.78 |

| 6 | Bornyl acetate | Monoterpene | 1285 | 1285 | 0.32 |

| 7 | α-Terpinyl acetate | Monoterpene | 1350 | 1352 | 3 |

| 8 | α-Ylangene | Sesquiterpene | 1375 | 1374 | 0.47 |

| 9 | α-Copaene | Sesquiterpene | 1376 | 1369 | 0.3 |

| 10 | β-Bourbonene | Sesquiterpene | 1384 | 1383 | 2.54 |

| 11 | β-Cubebene | Sesquiterpene | 1390 | 1387 | 1.1 |

| 12 | β-Elemene | Sesquiterpene | 1391 | 1390 | 0.45 |

| 13 | Longifolene | Sesquiterpene | 1402 | 1400 | 0.56 |

| 14 | β-Caryophyllene | Sesquiterpene | 1418 | 1422 | 18.45 |

| 15 | α-Humulene | Sesquiterpene | 1453 | 1452 | 3.78 |

| 16 | Germacrene D | Sesquiterpene | 1484 | 1484 | 35.72 |

| 17 | β-Selinene | Sesquiterpene | 1488 | 1486 | 0.38 |

| 18 | α-Muurolene | Sesquiterpene | 1499 | 1495 | 1.13 |

| 19 | γ-Cadinene | Sesquiterpene | 1513 | 1510 | 2.38 |

| 20 | δ-Cadinene | Sesquiterpene | 1523 | 1522 | 5.53 |

| 21 | α-Cadinene | Sesquiterpene | 1538 | 1534 | 0.38 |

| 22 | α-Calacorene | Sesquiterpene | 1546 | 1540 | 0.38 |

| 23 | Caryophyllene oxide | Sesquiterpene | 1581 | 1582 | 2.95 |

| 24 | Isolongifolanone | Sesquiterpene | 1613 | 1613 | 1.49 |

| 25 | α-Cadinol | Sesquiterpene | 1654 | 1658 | 3.15 |

aKovats index.

bTotal ion chromatogram.

Polyphenolic contents

An equation was obtained from the F-C test results using a scatter graph based on the GA standard curve. Curve’s equation was determined to be  , with R2 equaled to 0.9932. Polyphenolic content of each gram of PEBHAE was equal to 364 ± 5 mg of GA.

, with R2 equaled to 0.9932. Polyphenolic content of each gram of PEBHAE was equal to 364 ± 5 mg of GA.

Radical scavenging activity

PEBHAE showed stronger AA compared with PENVO. IC50 of GA, PEBHAE, and PENVO were 0.95, 4.37, and 0.98 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 1). PENVO showed the highest AA at 1 μg/ml, and its antioxidant capacity was not increased at higher concentrations. PEBHAE showed higher AA compared with PENVO, with the former having a maximum AA of 92% and the latter showing 51% AA.

Figure 1 .

Antioxidant activity (AA) of different concentrations of (A) Pinus eldarica needle volatile oil (PENVO), (B) Pinus eldarica bark hydroalcoholic extract (PEBHAE), and (C) gallic acid (GA).

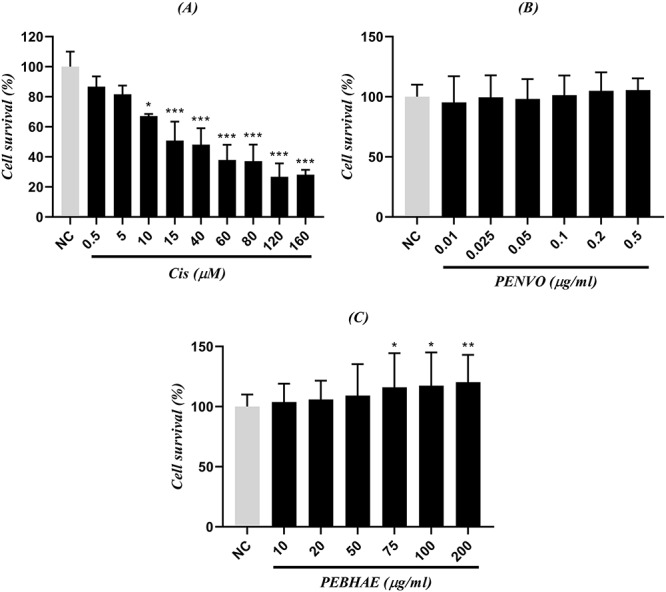

MTT assay

Cisplatin significantly inhibited the growth of HUVECs to less than 40% on high concentrations and its IC50 was determined to be 15 μM. This concentration was used to investigate the protective effects of both PENVO and PEBHAE on HUVECs. Moreover, neither PENVO nor PEBHAE reduced the cell's viability, which explains their safety in HUVECs. However, high concentrations of PEBHAE (75, 100, and 200 μg/ml) had mitogenic effects on the cells (i.e. cells were divided more compared to the NC) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 .

comparison between NC and different concentrations of (A) cisplatin (Cis), (B) PENVO, and (C) PEBHAE; NCs are cells that received nothing but cell medium and no other reagent was added to them; each group is being represented as mean ± SD (n = 3); signs (**) and (*) show statistical significance difference (P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively) compared to NC.

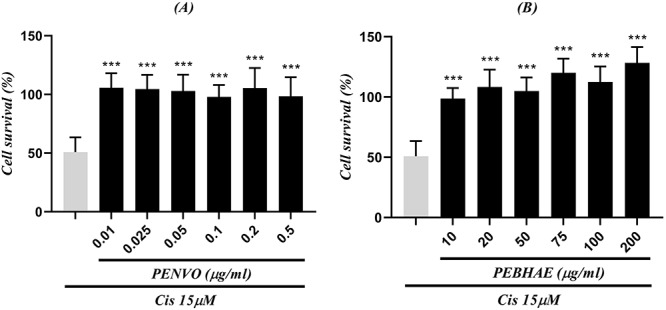

Effect of P. eldarica on HUVECs treated with cisplatin

To investigate the cytoprotective effects of PEBHAE and PENVO, cells were first incubated with cisplatin. After 1 h, the medium was changed and cells were treated with either PENVO or PEBHAE as the protective agent. Both PENVO and PEBHAE showed cytoprotective effects in all concentrations. PEBHAE showed stronger cell protective effects compared with PENVO (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 .

comparison between positive control (first column which shows cells that received only cisplatin with a concentration of 15 μM) and cells that were incubated with different concentrations of (A) PENVO and (B) PEBHAE and cisplatin (Cis); each group is being represented as mean ± SD (n = 3); and (***) show statistical significance difference (P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively) compared to positive control

Comet assay results

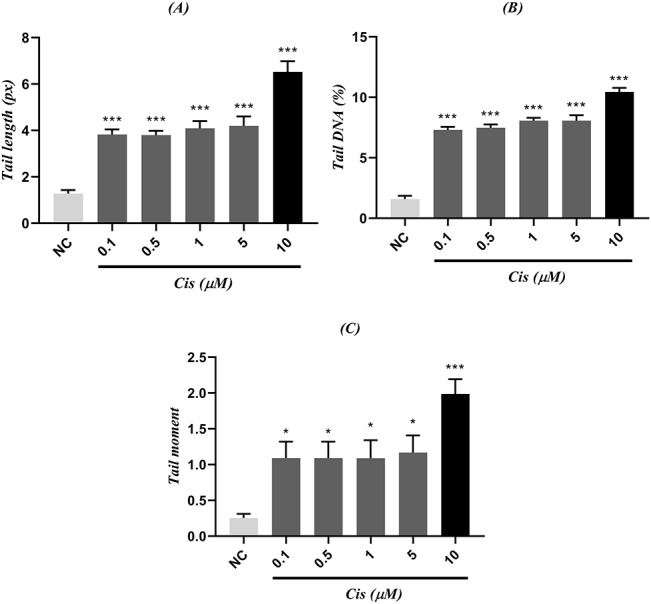

Effect of cisplatin on HUVECs

To determine the optimum genotoxic concentration of cisplatin, HUVECs were incubated with various concentrations of cisplatin (0.1~500 μM) for 24 h (Fig. 4). Concentrations below 5 μM did not represent ideal genotoxicity, and concentrations above 150 μM resulted in cell death. Cisplatin with a concentration of 10 μM showed optimum genotoxicity compared with other concentrations, thereby this concentration was used for further investigations.

Figure 4 .

comparison between (A) tail length, (B) tail DNA, (C) tail moment of different concentrations from cisplatin (Cis) and NC; NCs are cells that received nothing but cell medium; each group is being represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); signs (*) and (***) show statistical significance difference (P < 0.05, and P < 0.001, respectively) compared to NC.

Effect of P. eldarica on HUVECs

Cells were incubated with desired concentrations of either PEBHAE or PENVO for 24 h. As results are represented in Table 2, different concentrations of PEBHAE and PENVO were compared to the negative group (cells that received only cell medium without any other agents). Results indicate that none of the concentrations of both PENHAE and PENVO were statistically significant in tail length, tail DNA, and tail moment parameters. Hence, desired concentrations of extract and volatile oil were not genotoxic on HUVECs.

Table 2.

comparison between three parameters (tail length, tail %DNA, and tail moment) of different concentrations of PEBHAE, PENVO, and NC; cells that received nothing but cell medium were used as NC group

| Compound | Concentration | Tail length | Tail %DNA | Tail moment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEBHAE | 0.5 | 1.77 | 2.40 | 0.33 |

| 1 | 1.79 | 2.42 | 0.34 | |

| 5 | 1.82 | 2.44 | 0.34 | |

| 10 | 1.75 | 2.43 | 0.33 | |

| 20 | 1.80 | 2.34 | 0.33 | |

| 40 | 1.76 | 2.40 | 0.32 | |

| PENVO | 0.005 | 1.49 | 0.83 | 0.41 |

| 0.01 | 1.48 | 0.78 | 0.40 | |

| 0.025 | 1.34 | 0.66 | 0.30 | |

| 0.05 | 1.51 | 0.75 | 0.36 | |

| 0.1 | 1.57 | 0.92 | 0.45 | |

| 0.2 | 1.62 | 0.99 | 0.47 | |

| NC | 1.32 | 1.54 | 0.25 |

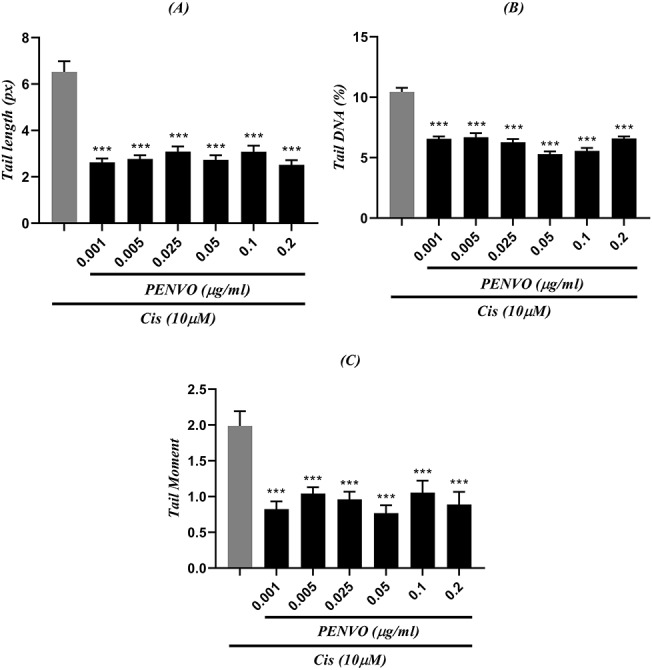

Effect of P. eldarica on cisplatin-induced DNA damage

HUVECs were incubated with either concentrations of PEBHAE or PENVO for 24 h. Then, medium was washed using PBS and the cells were incubated with cisplatin for another 24 h. The results of comet assay were analysed after a 48-h incubation period. All concentrations of both PEBHAE- (Fig. 5) and PENVO-treated groups (Fig. 6) were statistically significant in tail length, DNA tail, and tail moment parameters compared with cisplatin 10 μM, which indicates their genoprotective effects against cisplatin. Also, photos taken from samples are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 5 .

comparison between (A) tail length, (B) tail %DNA, and (C) tail moment of cisplatin (Cis) with different concentrations of PEBHAE and positive control (first column which represents cells that received only cisplatin with a concentration of 15 μM); each group is being represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); sign (***) shows statistical significance difference (P < 0.001) compared to positive control.

Figure 6 .

comparison between (A) tail length, (B) tail DNA, and (C) tail moment of cisplatin (Cis) with different concentrations of PENVO and positive control (first column which represents cells that only received cisplatin with a concentration of 15 μM); each group is being represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); sign (***) shows statistical significance difference (P < 0.001) compared to positive control.

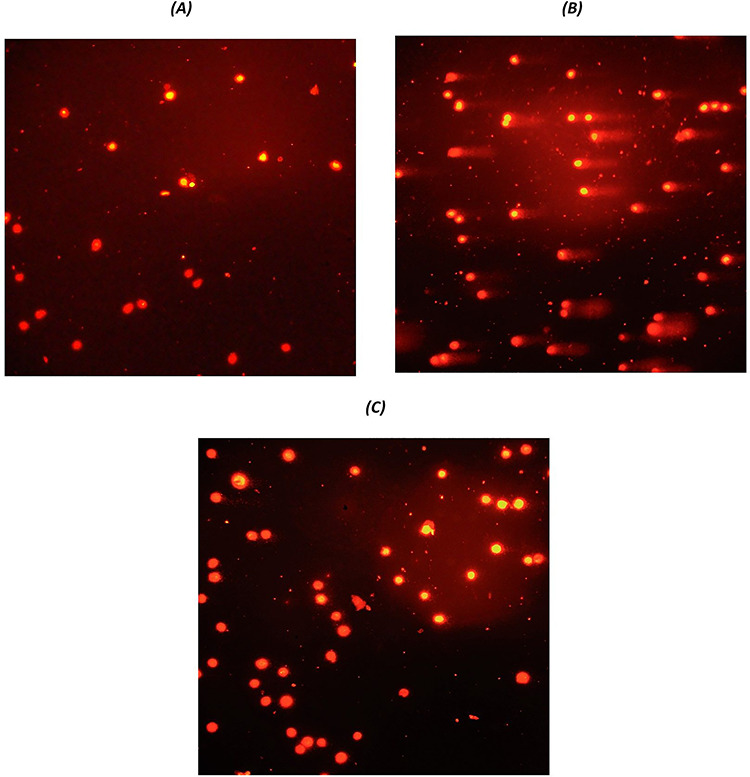

Figure 7 .

pictures taken from comet assay; (A) cells that received nothing but cell medium (NC), (B) cells treated with cisplatin 10 μM (positive control), and (C) protective agent along with cisplatin 10 μM.

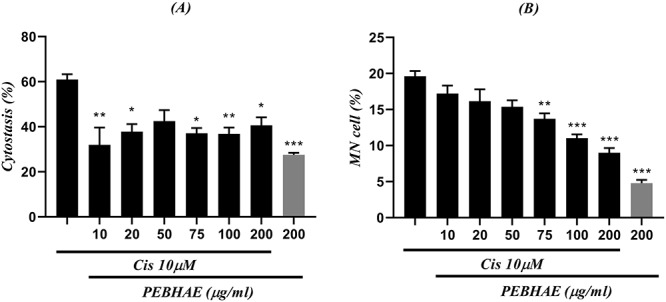

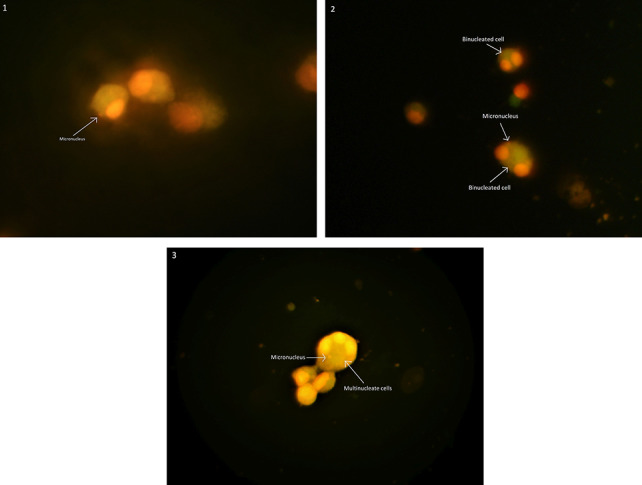

Micronucleus assay

The highest concentration of PEBHAE was used to ensure no micronucleus (MN) will be formed and therefore safety of PEBHAE will be assured. Cells that were treated with PEBHAE alone showed less MN formation compared with the positive control (cisplatin with a concentration of 10 μM). All concentrations of PEBHAE lowered MN formation induced by cisplatin on HUVECs (Table 3,Fig. 8), which indicates the reduction of genotoxicity caused by cisplatin. Photos taken of samples are shown in Fig. 9.

Table 3.

comparison of different concentrations of PEBHAE in MN assay

| Cyto B (4 μg/ml) for 28 h | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono N | Bi N | Multi N | MN | CBPI | RI | Cytostasis (%) | |

| NC | 400 | 160 | 8 | 12 | 1/31 | ||

| Positive control (cisplatin, 10 μM) | 612 | 72 | 7 | 135 | 1/12 | 46/93 | 60/99 |

| PEBHAE only (200 μg/ml) | 436 | 116 | 5 | 29 | 1/23 | 76/74 | 27/48 (***) |

| Cisplatin 10 μM + | |||||||

| PEBHAE, 10 μg/ml | 460 | 96 | 12 | 97 | 1/22 | 63/39 | 31/97 (**) |

| PEBHAE, 20 μg/ml | 474 | 96 | 8 | 93 | 1/20 | 63/16 | 37/87 (*) |

| PEBHAE, 50 μg/ml | 481 | 86 | 9 | 88 | 1/18 | 56/80 | 42/50 |

| PEBHAE, 75 μg/ml | 492 | 98 | 8 | 82 | 1/20 | 64/70 | 37/12 (*) |

| PEBHAE, 100 μg/ml | 486 | 99 | 10 | 65 | 1/20 | 65/13 | 36/81 (**) |

| PEBHAE, 200 μg/ml | 489 | 93 | 8 | 53 | 1/19 | 61/62 | 40/62 (*) |

Data are expressed as mean (n = 3). Signs (*), (**), and (***) represent statistically significant difference (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively) compared with positive control (i.e. cells that received only cisplatin with a concentration of 10 μM). Cyto B, cytochalasin B; Mono N, mono nucleated cell; Bi N, binucleated cell; Multi N, multi-nucleated cell; CBPI, cytokinesis-block proliferation index; RI, replicative index.

Figure 8 .

results obtained from (A) cytostasis (%) and (B) MN/total cell ratio are presented in this figure; each chart compares cells treated with both cisplatin (Cis) and different concentrations of PEBHAE and positive control (first column of both charts which shows cells that were treated with just 10 μM of cisplatin); data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); signs (*), (**), and (***) represent statistically significant difference (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively) compared to cisplatin

Figure 9 .

pictures taken from cells after MN assay; (A) mononucleosis cells, (B) binucleated cells with MN, and (B) multinucleate cells with MN

Discussion

Extracts of different Pinus species (i.e. Pinus nigra, Pinus brutia, Pinus pinea, Pinus sylvestris, and P. maritime) have been suggested as rich sources of phenolic content resulting in their high AA. Among different phenolic compounds, taxifolin is stated as the main component in P. brutia [36]. Moreover, phytochemical analysis of P. eldarica’s bark extract states taxifolin and catechin as its main components [14]. Our results from the F-C test suggest that PEBHAE proved to have high amounts of phenolic compounds, which explains its high antioxidant capacity.

Terpenes are also potential antioxidants, which act by ROS scavenging activities or by elevating the antioxidant levels in the body. This feature of terpenes could be used in order to protect against different complications caused by ROS in various diseases, including cancer [37]. One study states germacrene D (26.6%), β-caryophyllene (17.1%), and α-pinene (11.8%) as the most abundant components in the volatile oil obtained from P. eldarica’s leaves collected on July [38]. Another report mentions β-caryophyllene (14.8%), germacrene D (12.95%), and α-terpinenyl acetate (8.15%) as the major constituents of the leaf’s oil derived from the same plant, with samples being collected in November [39]. Several factors could affect the plant’s yield of volatile oil. Seasons when samples were collected, and environmental conditions such as temperature, water, and moisture, could result in changes between profiles of different volatile oils that were obtained from the samples collected at different times [40]. Our GC–MS result suggests that PENVO is rich in terpenes (both monoterpenes and sesquiterpene) and our analysis showed that, under studied conditions, PENVO’s main components were germacrene D (35.72%), β-caryophyllene (18.45%), and δ-cadinene (5.53%). Moreover, previous studies have also confirmed the antioxidant properties of germacrene D [41, 42].

Several studies have indicated the antioxidant properties of different pine trees and their potential as protective agents [26, 43–45]. Our results indicate that PENVO showed no linear association between concentration and AA at concentrations above 1 μg/ml. Highest AA (57.9%) among volatile oil concentrations was observed at 250 μg/ml concentration. Also, as concentrations were increased from 0.005 to 1 μg/ml, the AA improved, but more antioxidant potential was not observed at concentrations above 1 μg/ml. Poor solubility of PENVO in DPPH’s medium could affect its AA [41]. PEBHAE showed a strong AA with a linear association between concentration and antioxidant capacity. PEBHAE showed maximum AA (91%) at 25 μg/ml, and no increase in antioxidant capacity was observed on higher concentrations. These results state that both PENVO and PEBHAE have a limit to their antioxidant capacity and there is not necessarily more AA as concentrations are increased. This could be due to their limited constituents responsible for scavenging free radicals. Moreover, PEBHAE showed higher efficacy compared to PENVO. Also, PEBHAE proves to have better ROS scavenging activity compared to extracts obtained from P. maritime.

The results of the MTT assay indicated that both PENVO and PEBHAE are not cytotoxic. Interestingly, PEBHAE increased cell proliferative rate on higher concentrations, which could be due to its mitogenic effects. A study had previously stated that P. maritime’s bark extract has anti-aging and mitogenic effects [46]. Since P. eldarica and P. maritime have a similar polyphenolic profile, the observed mitogenic effects could be related to the phenolic compounds found in PEBHAE. Cisplatin’s IC50 was determined to be 15 μM; therefore, this concentration was used for further investigating the cytoprotective effects of both PEBHAE and PENVO. All of the concentrations of both PEBHAE and PENVO showed cytoprotective effects against cisplatin. Previously, there was a report suggesting P. eldarica’s bark extract may protect HUVECs against H2O2, which is a known agent responsible for producing free radicals [16]. Since both PENVO and PEBHAE showed AA in DPPH assay, their cytoprotective effects may be related to their ability to scavenge free radicals produced by cisplatin.

Neither PENVO nor PEBHAE showed any DNA damage individually under a 24-h period of incubation on HUVECs. Optimum genotoxicity of cisplatin was observed at the concentration of 10 μM; hence, this concentration was used to investigate the genoprotective effects of both PENVO and PEBHAE. Unlike what was expected, as cisplatin’s concentration was increased, comet parameters (i.e. tail length, DNA percent in the tail, and tail moment) were not increased. A study suggested that since one of cisplatin’s mechanisms of action is to form crosslinks inter-/intra-DNA strands, the DNA migration in the electrophoresis phase is interrupted and comets would not be formed [47]. Previous studies have also stated the protective effects of Pycnogenol® (extract obtained from P. maritime’s bark) against DNA damage, using comet assay in different cell lines [18, 19, 48]. Our findings suggest that both PENVO and PEBHAE were genoprotective against the genotoxicity induced by cisplatin. Reports indicate that phenolic compounds like proanthocyanidin and procyanidin are responsible for the protective effects of other pine trees against DNA damage due to their high AA [49, 50]. The protective effects of PEBHAE could be due to its rich phenolic profile. Also, germacrene D as the main component of PENVO proves to have an antioxidant capacity as indicated by previous studies [41, 42]. PENVO may represent its genoprotective effects thorough its antioxidant capacity by eliminating the ROS generated by cisplatin.

As suggested by OECD guideline (No. 487), to obtain the maximum number of binucleated cells, cytochalasin B should be incubated with cells for at least 1.5-2 cell cycle divisions [35]. Our results showed that binucleated cells are formed with a concentration of 4 μg/ml from cytochalasin B, when this agent is incubated for 28 h with cells. To obtain swelled cells, both sodium citrate and potassium chloride can be used, but our findings suggest that potassium chloride showed optimum cell swelling after 45 min. Thereby, hypotonic potassium chloride was used instead of sodium citrate. Percent of cytostasis was calculated to ensure samples had no cytotoxic effect on cells. Also, the MN/total cell ratio was measured in different groups to determine their genotoxic/protective effects. To ensure that PEBHAE has no toxicity for cells, the highest concentration of PEBHAE was incubated with cells individually without the addition of cisplatin. Results from MN assay under studied conditions indicate that PEBHAE alone is not toxic for cells and it also does not induce genotoxicity. Cells treated with both cisplatin and different concentrations of PEBHAE (with a 24-h incubation period in-between) had less MN formation compared with the positive control (cells that were incubated with 10 μM of cisplatin alone). Also, these groups showed decreased cytostasis percent compared with the positive control, which signifies that they have neutralized the cytotoxicity of cisplatin. Several studies have also stated the protective effects of different agents with antioxidant properties against cisplatin-induced genotoxicity via MN assay [51–53]. Since PEBHAE is a rich source of antioxidant components, less MN formation could be due to its ability to scavenge free radicals generated by cisplatin.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that both PENVO and PEBHAE are a major source of antioxidant components, with the latter being stronger. Also, not only both agents (i.e. PENVO and PEBHAE) had no cytotoxic effects on normal cells but also they could protect cells from the cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity. Both PENVO and PEBHAE could be used to stop the devastating progression of free radicals generated by cisplatin and thereby have genoprotective effects. However, further in vivo studies are recommended to ensure the safety and protective profile of P. eldarica.

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and their staff for supporting this research.

Contributor Information

Amin Sharifan, Department of Pharmacology, Isfahan Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Mahmoud Etebari, Department of Pharmacology, Isfahan Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Behzad Zolfaghari, Department of Pharmacognosy, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Mehdi Aliomrani, Department of Pharmacology, Isfahan Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Funding

This work was funded by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences under the grant number 398609.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram Iet al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oun R, Moussa YE, Wheate NJ. The side effects of platinum-based chemotherapy drugs: a review for chemists. Dalton Trans 2018;47:6645–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Unger FT, Klasen HA, Tchartchian Get al. DNA damage induced by cis-and carboplatin as indicator for in vitro sensitivity of ovarian carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer 2009;9:359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aref N, Mina M, Mahmoud A, Mehdi A. 4-Hydroxyhalcone effects on cisplatin-induced genotoxicity model. Toxicol Res 2021, tfaa091. 10.1093/toxres/tfaa091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Florea A-M, Büsselberg D. Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: cellular mechanisms of activity, drug resistance and induced side effects. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:1351–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen SM, Lippard SJ. Cisplatin: from DNA damage to cancer chemotherapy. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 2001;67:93–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rice-Evans C, Miller N, Paganga G. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci 1997;2:152–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai Y, Luo Q, Sun Met al. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sci 2004;74:2157–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martínez-Vilalta J, Sala A, Piñol J. The hydraulic architecture of Pinaceae–a review. Plant Ecol 2004;171:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Phillips GC, Gladfelter HJ. Eldarica Pine, Afghan Pine (Pinus eldarica Medw.). In: Trees III. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1991, 269–87. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sadeghi H, Khavarinezhad RA, Falahian FAet al. The effects of NaCl salinity on the growth and mineral uptake of Tehran pine (Pinus eldarica M.). Iran J Hortic Sci Technol 2007;8:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma C, Wang Q, Liu M. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of pine polyphenols from three Pinaceae species in vitro. Southwest China J Agric Sci 2016;29:1063–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nikolova M, Peev D. Preliminary investigation of antioxidant potential and flavonoid content of Pinaceae species needles. In: Proceedings of the Fifth Conference on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Southeast European Countries, (5th CMAPSEEC), Brno, Czech Republic, 2-5 September, 2008. Brno, Czech Republic: Mendel University of Agriculture and Forestry in Brno, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iravani S, Zolfaghari B. Phytochemical analysis of Pinus eldarica bark. Res Pharm Sci 2014;9:243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huseini HF, Anvari MS, Khoob YTet al. Anti-hyperlipidemic and anti-atherosclerotic effects of Pinus eldarica Medw. nut in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. DARU J Pharm Sci 2015;23:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Babaee F, Safaeian L, Zolfaghari Bet al. Cytoprotective effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Pinus eldarica bark against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in human endothelial cells. Iran Biomed J 2016;20:161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sadeghi M, Zolfaghari B, Jahanian-Najafabadi Aet al. Anti-pseudomonas activity of essential oil, total extract, and proanthocyanidins of Pinus eldarica Medw. Bark. Res Pharm Sci 2016;11:58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taner G, Aydın S, Aytaç Zet al. Assessment of the cytotoxic, genotoxic, and antigenotoxic potential of Pycnogenol® in in vitro mammalian cells. Food Chem Toxicol 2013;61:203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Becit M, Aydin S. An in vitro study on the interactions of Pycnogenol® with Cisplatin in human cervical cancer cells. Turkish J Pharm Sci 2020;17:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuo AL, Figueiredo CR, Arruda DCet al. α-Pinene isolated from Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae) induces apoptosis and confers antimetastatic protection in a melanoma model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011;411:449–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Minaiyan M, Ghannadi A, Etemad Met al. A study of the effects of Cydonia oblonga Miller (quince) on TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Res Pharm Sci 2012;7:103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adams RP. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, Vol. 456. Carol Stream, IL: Allured publishing corporation, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swigar AA, Silverstein RM. Monoterpenes: Infrared, Mass, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR Spectra, and Kováts Indices. Milwaukee: Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blainski A, Lopes G, Mello J. Application and analysis of the folin ciocalteu method for the determination of the total phenolic content from Limonium brasiliense L. Molecules 2013;18:6852–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier M-E, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci Technol 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Apetrei CL, Tuchilus C, Aprotosoaie ACet al. Chemical, antioxidant and antimicrobial investigations of Pinus cembra L. bark and needles. Molecules 2011;16:7773–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Etebari M, Ghannadi A, Jafarian-Dehkordi Aet al. Genotoxicity evaluation of aqueous extracts of Cotoneaster discolor and Alhagi pseudalhagi by comet assay. J Res Med Sci 2012;17:S237–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aliomrani M, Jafarian A, Zolfaghari B. Phytochemical screening and cytotoxic evaluation of Euphorbia turcomanica on Hela and HT-29 tumor cell lines. Adv Biomed Res 2017;6:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aliomrani M, Jafarian A, Zolfaghari B. Cytotoxicity of Euphorbia bungei on HeLa and HT29 tumor cells. Res Pharm Sci 2012;7:130. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983;65:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Plumb JA. Cell sensitivity assays: the MTT assay. Cancer Cell Cult 2004;88:165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RRet al. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res 1988;175:184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sadeghi F, Etebari M, Roudkenar MHet al. Lipocalin2 protects human embryonic kidney cells against cisplatin–induced genotoxicity. Iran J Pharm Res IJPR 2018;17:147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Belpaeme K, Cooreman K, Kirsch-Volders M. Development and validation of the in vivo alkaline comet assay for detecting genomic damage in marine flatfish. Mutat Res Toxicol Environ Mutagen 1998;415:167–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Économiques O. de coopération et de développement. Test No. 487: In vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yesil-Celiktas O, Ganzera M, Akgun Iet al. Determination of polyphenolic constituents and biological activities of bark extracts from different Pinus species. J Sci Food Agric 2009;89:1339–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gonzalez-Burgos E, Gómez-Serranillos MP. Terpene compounds in nature: a review of their potential antioxidant activity. Curr Med Chem 2012;19:5319–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Afsharypuor S, San’aty F. Essential oil constituents of leaves and fruits of Pinus eldarica Medw. J Essent oil Res 2005;17:327–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sarvmeili N, Jafarian-Dehkordi A, Zolfaghari B. Cytotoxic effects of Pinus eldarica essential oil and extracts on HeLa and MCF-7 cell lines. Res Pharm Sci 2016;11:476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharma S, Adams JP, Sakul Ret al. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) essential oil yields affected by environmental and physiological changes. J Sustain For 2016;35:417–30. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Casiglia S, Bruno M, Bramucci Met al. Kundmannia sicula (L.) DC: a rich source of germacrene D. J Essent oil Res 2017;29:437–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Noriega P, Guerrini A, Sacchetti Get al. Chemical composition and biological activity of five essential oils from the ecuadorian Amazon rain forest. Molecules 2019;24:1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jiang Y, Han W, Shen Tet al. Antioxidant activity and protection from DNA damage by water extract from pine (Pinus densiflora) bark. Prev Nutr food Sci 2012;17:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dhibi M, Issaoui M, Brahmi Fet al. Nutritional quality of fresh and heated Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis mill.) seed oil: trans-fatty acid isomers profiles and antioxidant properties. J Food Sci Technol 2014;51:1442–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wardani G, Ernawati K, Eraiko K, Sudjarwo SA. ``The role of antioxidant activity of chitosan-pinus merkusii extract nanoparticle in against lead acetate-induced toxicity in rat pancreas. Vet Med Int 2019;2019:6. Article ID 9874601. 10.1155/2019/9874601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu FJ, Zhang YX, Lau BHS. Pycnogenol enhances immune and haemopoietic functions in senescence-accelerated mice. Cell Mol Life Sci C 1998;54:1168–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Meneghin Mendonça L, Cristina Dos Santos G, Alves Dos Santos Ret al. Evaluation of curcumin and cisplatin-induced DNA damage in PC12 cells by the alkaline comet assay. Hum Exp Toxicol 2010;29:635–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Taner G, Aydın S, Bacanlı Met al. Modulating effects of pycnogenol® on oxidative stress and DNA damage induced by sepsis in rats. Phyther Res 2014;28:1692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nelson AB, Lau BHS, Ide Net al. Pycnogenol inhibits macrophage oxidative burst, lipoprotein oxidation, and hydroxyl radical-induced DNA damage. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 1998;24:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Senthilmohan ST, Zhang J, Stanley RA. Effects of flavonoid extract Enzogenol® with vitamin C on protein oxidation and DNA damage in older human subjects. Nutr Res 2003;23:1199–210. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Giri A, Khynriam D, Prasad SB. Vitamin C mediated protection on cisplatin induced mutagenicity in mice. Mutat Res Mol Mech Mutagen 1998;421:139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Santos GC, Mendonça LM, Antonucci GAet al. Protective effect of bixin on cisplatin-induced genotoxicity in PC12 cells. Food Chem Toxicol 2012;50:335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chandrasekar MJN, Bommu P, Nanjan Met al. Chemoprotective effect of Phyllanthus maderaspatensis. In modulating cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and genotoxicity. Pharm Biol 2006;44:100–6. [Google Scholar]