ABSTRACT

High prevalence of teenage pregnancy in low-income countries impacts health, social, economic, and educational situations of teenage girls. To acquire better understanding of factors leading to high prevalence of teenage pregnancy in rural Lindi region, Tanzania, we explored perspectives of girls and key informants by conducting a facility-based explorative qualitative study according to the grounded theory approach. Participants were recruited from Mnero Diocesan Hospital using snowball sampling, between June and September 2018. Eleven pregnant teenagers, two girls without a teenage pregnancy, and eight other key informants were included. In-depth interviews (including photovoice) and field observations were conducted. Analysis of participant perspectives revealed five main themes: 1) lack of individual agency (peer pressure, limited decision-making power, and sexual coercion); 2) desire to earn money and get out of poverty; 3) dropping out of school contributing to becoming pregnant; 4) absence of financial, material, psychological, or emotional support from the environment; and 5) limited access to contraception. A majority of girls reported the pregnancy to be unplanned, whereas some girls purposely planned it. Our findings and the resulting conceptual framework contribute to a new social theory and may inform national and international policies to consider the needs and perspectives of teenagers in delaying pregnancy and promoting sexual and reproductive health in Tanzania and beyond.

Summary Box: What is already known on this subject? Worldwide, an estimated 23 million girls under the age of 20 years are pregnant annually, indicating that teenage pregnancy comprises a substantial global health problem.1 The particularly high burden of teenage pregnancy in low-income countries, such as Tanzania, causes serious health and social problems.1–4,6–9 The WHO developed guidelines on preventing teenage pregnancy, but national statistics in Tanzania reveal high—and even increasing—numbers.3 Therefore, exploration of factors contributing to teenage pregnancy is needed.

What this study adds?

Our findings based on local perceptions enabled the construction of a theoretical framework incorporating factors contributing to the high and increasing numbers of teenage pregnancies in rural Tanzania. This framework and the greater insight into perceptions and challenges of Tanzanian teenagers to delay pregnancy may inform national and international policies to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights of teenagers.

INTRODUCTION

Teenage pregnancy, defined as pregnancy below the age of 20 years, has a high prevalence in low-income countries, such as Tanzania, where more than half of girls give birth before they turn 19 years.1–4 This is particularly a problem in rural areas, where 32% of teenagers became pregnant in 2015–2016 compared with 19% in urban areas.3,5 In Mnero Diocesan Hospital, situated in a rural area of Lindi region in the south of Tanzania, 34.9% of all women who gave birth were teenagers.

Teenage pregnancy is associated with a high risk of obstetric complications such as eclampsia, puerperal endometritis, obstetric fistula, obstructed labor, preterm birth, low birth weight, severe neonatal conditions, and neonatal mortality.1,6–8 Moreover, teenagers often face domestic violence, school dropout, and reduced employment opportunities. They are at increased risk of unsafe abortion.1,4,9

Between 2009 and 2011, the WHO produced guidelines on preventing teenage pregnancy and its complications in low-income countries.10,11 These guidelines provide recommendations on how to reduce teenage pregnancies by preventing marriage before the age of 18 years, reducing unsafe abortions, increasing knowledge related to pregnancy prevention, increasing use of maternity services and contraception, and preventing coerced sexual intercourse.10 Despite these guidelines, national statistics reveal high—and even increasing–rates of teenage pregnancy in rural areas of Tanzania.3 To gain insights into factors contributing to teenage pregnancy in Lindi region, we conducted a qualitative study of local perceptions.

METHODS

Research setting, research sample, and recruitment.

This qualitative study using a grounded theory approach was carried out between June and September 2018 in Mnero Diocesan Hospital located in Lindi region in the southern part of Tanzania. Participants were recruited by snowball sampling. Initially, 11 in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with girls admitted to the obstetric ward or attending the antenatal clinic. Background characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background characteristics

| Teenage girl (n = 11, 12 pregnancies)* | Planned (n = 5) | Unplanned (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset of pregnancy (years) | ||

| 15 | 0 | 2 |

| 16 | 1 | 2 |

| 17 | 4 | 1 |

| 18 | 0 | 2 |

| Highest education | ||

| Primary | 3 | 4 |

| Secondary incomplete | 2 | 2 |

| Secondary complete | 0 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 2 | 0 |

| Unmarried | 3 | 7 |

One participant responded to an unplanned pregnancy at the age of 15 years and a planned pregnancy at the age of 17 years.

Key informants had been residents in Lindi region for at least 1 year. In-depth interviews were conducted with three healthcare workers: the doctor in charge, who was the only doctor meeting the criterion of living in Lindi region for at least 1 year, and two midwives, who were conveniently selected because they were available at the time of the interview. Other respondents of interest emerged through theoretic sampling. We conducted one IDI with two unyago teachers (known as kungwis) at the same time, both members of the Mwera tribe. In addition, we conducted IDI’s with a primary school teacher, a secondary school teacher, and a traditional healer. To contrast emerging theories, two IDI’s were conducted with girls without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years. Altogether, the total number of participants was 21. The sample size was determined by theoretical saturation.

Data collection.

Data were collected through semi-structured IDI’s translated by a native speaker into English. Main topics covered in the interview guide included general demographics, examples of teenage pregnancy in the environment, personal situation (pregnant teenagers and teenagers who had avoided pregnancy), personal views regarding teenage pregnancy, contributing factors to teenage pregnancy, prevention and reproductive health education, culture and community, religion, and support. To ensure privacy and safety, all interviews were conducted in either a private office or a participant’s home. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. For triangulation purposes using photovoice, a documentary in Kiswahili discussing teenage pregnancy in Tanzania was shown and discussed after the interview.12 This documentary included four life stories of pregnant teenagers. A variety of subjects were discussed in the documentary: arranged marriage, poverty, sexual coercion, rape, sexual violence, lack of individual agency, school dropout, material and emotional support, and lack of reproductive health education. Participants were asked to explain their views on the documentary and provide possible examples of the documentary’s subjects from within their personal environment.

Later on, field observations were performed to visualize emerged themes. Visual data were extracted by visiting a traditional unyago ceremony, a local bar, the hospital, or primary or secondary schools and traveling by local transport. In addition, records and field notes of observations were collected in memos. Data were prepared for analysis by allocating quotations and codes in Atlas.ti 8 data management software (2018, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). A reflective journal and memos were kept to track research progress and theory development.

Data analysis.

A grounded theory inductive approach was applied.13,14 Alternating cycles of empirical data collection, data analysis, and peer review allowed for adjustment of data collection methods within each successive cycle. Data analysis was conducted by cycles of open, axial, and selective coding.15 Through codes and categories, main themes were uncovered and analyzed for relation, variation, and similarities. Constant comparative analysis between and within cases was performed. Networks and word clouds were created. The use of a query tool allowed for the selection of quotations to support findings. The set of categories comprised total volume of data. Final existent themes have produced a coherent grounded theory including sensitizing concepts, allowing for answering the research question.

Research ethics.

All participants agreed to participate by providing oral and written informed consent. All participants were provided with information regarding content of the research and an explanation of procedures and their rights allied to this study, including the right to withdraw any time. Given the sensitive character of the research subject matter, all interview questions were analyzed and revisited to ascertain appropriateness by the board of Mnero Diocesan Hospital, before initiating data collection. The VUMC ethical committee in Amsterdam declared not to object to publication of data collected outside the Netherlands. We have obtained institutional approval in Tanzania for our research protocols and for data collection, considered by the board of the Mnero Diocesan Hospital. The board of Mnero Diocesan Hospital ruled that further ethical approval was not necessary. Because the subject of this research addresses teenage pregnancy, the WHO guidelines for conducting safe and ethical research among teenage women were followed.16,17

RESULTS

Contributing factors.

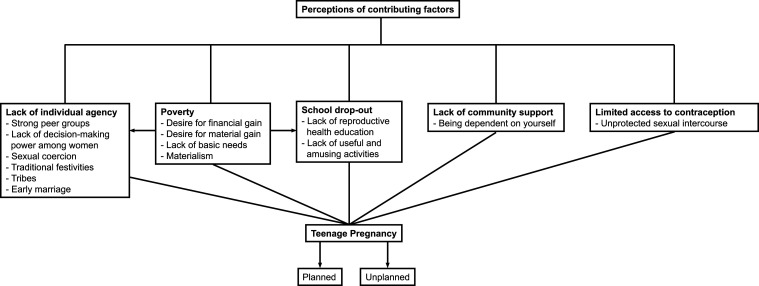

Data analysis revealed five themes concerning factors leading to teenage pregnancy, which were adopted into a conceptual framework (Figure 1). Lack of individual agency, poverty, school dropout, lack of community support, and limited access to contraception were perceived to contribute to teenage pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Perceptions of contribution factors.

Theme 1: Lack of individual agency.

A first theme that emerged focused on individual agency, or the ability of individuals to act independently and make their own choices. A majority of participants emphasized that peer groups limited individual agency. These groups included friends, relatives, and sexual partners.

“Peer groups promote attending sexual activities”…“because she is my friend, she can convince me to do that activity.”…“Girls should avoid to be in peer groups.” (Pregnant teenager) D21

According to several key informants, some community members considered their teenage children to be grown up and able to take care of themselves from the moment they finish primary education. These ideas influence local norms regarding early pregnancy.

“When children finish standard seven, it is time to get pregnant…now you have grown up. They finish at 13, 14, 15 years.” (Healthcare worker) D24

Another important cultural factor which limits individual agency is lack of decision-making power among women. Men seem to control sexual decision-making.

“I love you, I need you here, I need something... Saying no is not an option. Men are always like this in Africa.” (Pregnant teenager) D95

“Sometimes a man can make a girl pregnant because he is forcing her to have a baby. ‘I need a baby, I want you to carry the pregnancy.’” Pregnant teenager) D15

The desire to have sexual intercourse is not always shared by the girl. Sexual coercion has been defined as being psychologically, financially, or otherwise forced, pressured, threatened, or tricked into engaging in sexual activity.18

“Bribes like a soda, juice, or clothes are given by a man as a present. When it is given frequently, she is called into the house of the man. And then he starts to explain to her “okay, you know why I gave you the presents? It is because I love you, I want to be with you.” It is a kind of seduction.” (Pregnant teenager) D21

Participants emphasized the importance of communal justice within tribes. Members of these tribes tend to protect each other. As a result, they can easily engage in illegal practices such as child marriage, prostitution, sexual coercion, and rape. This system might affect the ability of teenagers to act independently and make their own choices.

“Because nowadays when you are known for raping, they just make their own judgement…Sometimes they can collect a lot of people and then when you are caught they say what did you do, you raped my young girl, and then sometimes they can even kill you. Although sometimes, the family can, if it only is a nearby boy who has done it, they can come and talk together and finish it.” (Healthcare worker) D20

Girls from the Mwera or Makonde tribe usually have unyago training, a traditional adulthood initiation rite that occurs between the age of 5 and 10 years.19–23 They will be isolated for 2–4 weeks and trained by kungwi, adult women chosen by their parents. Participants consider certain contents of unyago to contribute to teenage pregnancy because they can influence ideas and norms of children and may lead to early sexual intercourse. Mentioned contents are, for instance, how to perform suggestive dancing, how to please a husband, and how to practice sexual activities.

“So we are taught how to dance and how to satisfy a man. They always tell don’t start early, just wait until you become old enough. Then you can start using sex. But others mis-use that.” (Pregnant teenager) D95

A girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years underwent an alternative, more contemporary variant of unyago, without teachings about sexual practices. In her opinion, this protected her from teenage pregnancy.

“Conservative unyago contributes to early pregnancy due to the teachings…, marriage and pleasing men, they are taught how to do that. So at the end of the day they practice it, and they get pregnant at early age.” (girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20) D104

Eventually, unyago ends in a 24-hour traditional celebration. During field observations, authors attended such celebrations and found hundreds of people gathering outside the village. Girls were encouraged to have intercourse by women shouting repeatedly “Kantombe uyo uyo,” which means “Go and have sex.” This kind of peer pressure limits the individual agency of teenage girls.

“For us it is normal to talk like this. But you cannot always say this, “kamtombe uyo uyo,”...It is very offensive language.…In this period the behaviour is very bad, in unyago. In this period you can sleep with everyone, even though you are married.” (girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20) D48

Marriage under the age of 18 years is still common. This might be supported by local justice, which undermines the national laws against child marriage.24 Participants consider early marriage to be related with teenage pregnancy because cultural norms demand young couples to become pregnant, although they are mentally and physically not ready, which limits individual agency.

“We, muslim, teach the girls that when you reach puberty, then you are free, you are grown up, you are ready to get married. So that is why most of girls get married.” (Teacher) D98

“From our tradition, when you are getting married that means that you are going to get a child soon.”(healthcare worker) D20

Theme 2: Poverty and a resulting desire for financial gains.

Poverty may lead to a desire to improve the socioeconomic status. Nearly all participants displayed the desire for financial and material gains. The lack of primary needs might generate exploitation.25

“Poor life in general causes girls to find boys.., sleep with them and then they get money. Because of this poor life accidentally they become pregnant.” (Pregnant teenager) D16

“Girls can come to you and say: ‘We have a problem in our home, we don’t have food, we don’t have soap, I don’t have school uniform, I don’t even have exercise book, even today I don’t know what we are going to eat,…please can you help me? I can give you anything.. I just need food’…That is a seduction…At the end of the day you end up into sexual intercourse.” (Teacher) D98

Material good increase the social status of teenagers, also materialism was thought to contribute to having sex.

“When you see your fellows having nice clothes, nice materials, you have this desire to have the same as your fellow. As a result you enter into sexual activities and then you get pregnant” (Healthcare worker) D94

The lack of primary needs and materialism were also stated to result in prostitution or in early marriage because marriage includes the payment of dowry and men being responsible for livelihood.

Theme 3: School dropout.

Many participants revealed that school dropout contributes to the occurrence of teenage pregnancy. Girls will be deprived of reproductive health education. Pregnant teenagers seem to be aware of their lack of education.

“It was just a mistake. I lacked education…I didn’t know that condom prevents pregnancy…I only got primary school up to standard 5…I was sick…The teachers said you cannot continue the school because you are missing a long time. Then it ended there.” (Pregnant teenager) D96

Also, most participants explained that girls have lack of useful or amusing activities. As a result, they engage in sexual activities.

“After finishing school, most of them are just in the village. No permanent things to do. So it is very easy for them to engage in other things like sex.” (Healthcare worker) D20

Participants illustrated dropout as a result of poverty because of the lack of basic needs, poor health conditions, poor study environment at home, and ignorance of the importance of secondary education by either the parent or child.

“The government can provide free education, but it does not provide other facilities. For example school uniforms, exercise books,…Some of the parents are so ignorant, they are not educated and don’t know the importance of education. Some girls just don’t want to study.” (Teacher) D99

One girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years considered school attendance to be preventative in her own situation, by being focused on education instead of boyfriends.

“Education is the first thing for you to escape from getting pregnant below the age of 20 because most of the time you will be in school. Different from the one who is in primary school just standard seven, then she stays at home, what next? Pregnancy, marriage, et cetera.” (Girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years) D104

Theme 4: Lack of community support.

Generally, teenage mothers live in uncontrolled, unsupportive environments. Therefore, they depend themselves and are prone to teenage pregnancy. Parents frequently ignore their responsibility to carry out reproductive health education. This was found to contribute to a lack of knowledge concerning pregnancy prevention.

“Her mother and father separated. The father doesn’t know how to take good care of her, so she left school. After leaving from school she got pregnant.” (Pregnant teenager) D13

According to a girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years, parental attitudes protected her from teenage pregnancy.

”My parents were very strict and I was busy with school. So, I didn’t start sexual activities at early age.” (Girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years) D104

Some parents feel pressurized to bribe their daughters into marriage to receive dowry, which may contribute to early pregnancy.

“There was one girl in standard seven, she was bribed, the adults had chosen a man for her. They told that girl that she shouldn’t do good at exams. She followed the parents wish and then she failed and she got married. They earned money.” (Pregnant teenager after seeing videos of child marriages) D23

Theme 5: Limited access to health promotion and contraception.

Lack of health promotion such as posters in public areas or reproductive health education might increase teenage pregnancy. Also, failure to obtain free contraceptives and lack of privacy while asking for it might cause girls not to use contraceptives. Furthermore, girls use unreliable methods such as the calendar method, coitus interruptus, or traditional contraception. Last, contraception is criticized by religion and believed to cause infertility.

When a child which is quite young goes to the clinic to get an injection, they are afraid that they can get questions like: You already want an injection? Are you not a little bit young for this? And then the people start talking that she went to the clinic to get an injection,…It’s like a boundary for them to go there.” (Healthcare worker) D24

“Contraception causes infertility…especially injections. They will make you infertile because they are going to cause troubles to the follicles, the eggs. And especially those children, when they use injectables, noooo..., they are not allowed.” (Kungwi) D97

Undergoing an abortion is generally not accepted, which contributes to unwanted teenage pregnancies being continued.

“My mother is very close to me and was comforting me that you I have to deal with it, that I have to give birth to this child. Don’t do abortion.” (Pregnant teenager) D14

“I discourage abortion…If you get pregnant at young age, you should continue up until delivery. Because you might abort now, and then you might end up in infertility forever.” (Pregnant teenager) D96

Some participants deliberately planned to become pregnant as a normal consequence of marriage (see Table 1). Unmarried girls felt they were grown up and ready for childbearing. A majority reported their pregnancy to be unplanned. Finally, both girls without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years, as well as other key informants and pregnant teenagers, mentioned factors related to personality and individual behavior as crucial in leading to teenage pregnancy.

“My younger sister, she was 17 years. She got accidentally pregnant after primary school. She didn’t continue to secondary school. Our parents were very strict to us every day, but she didn’t want to understand, she had relationships. She was punished every day by our parents because of the behaviour. So people are different.” (Girl without a pregnancy before the age of 20 years) D104

DISCUSSION

Our study highlights important factors leading to the high teenage pregnancy rate in Tanzania, some of which were not described before. Perception of teenage girls and local community members revealed that teenage pregnancy is influenced by cultural factors, poverty, school dropout, poor parental support, and insufficient access to contraception.

Cultural factors interacting with the individual agency of teenagers, defined as the ability of individuals to act independently and make their own choices, were already found to contribute to teenage pregnancy in rural Tanzania. One of these factors includes peer pressure,26 previously described in neighboring Mtwara region.27 Especially in mid-adolescence, when teenage girls start developing their ideals, identity, and norms, peers are known to be important influencers.28 Particularly in sub-Saharan African countries, men are recognized as dominant and initiating sexual interactions.29,30 Gender role attitudes in sexual relationships among Tanzanian men often involve dominant behavior, in contrast to the submissive and obedient gender roles of young women.31 Furthermore, women are known to be vulnerable to sexual coercion.32,33 Sexual coercion was previously found to be associated with teenage pregnancies in African settings.30 In 2011, the WHO developed guidelines on preventing teenage pregnancies by addressing coerced sex.10 Evaluation of these guidelines and related interventions is required to develop effective programs, which should include programs targeting men, to accurately alter current norms and behaviors.30,34,35 The Constitutional Court of Tanzania recently declared that marriage under the age of 18 years is prohibited.24 A publication by the United Nations Population Fund and WHO preventative guidelines toward teenage pregnancies addressed the importance of preventing child marriage to reduce teenage pregnancy rates.8,10 Nevertheless, participants and recent literature indicate that child marriage still exists and is maintained by local justice systems.25 Current policies, programs, and guidelines should be reviewed to truly eliminate child marriage. Next, there is need for interventions regarding unyago. A study in the neighboring Mtwara region recognized the relation between the practice of unyago and teenage pregnancies, in terms of educating sexual practices, gender roles, and the encouragement to have sex with peers of their age after the adulthood initiation rite,36 as have other studies.21,23,37,38

Another prominent contributing factor was poverty. Living in poverty makes teenage girls more prone to pregnancy, and teenage mothers are more likely to live in poverty.39 In absence of basic needs, poverty is known to induce exploitation by exchanging sexual intercourse for money or food.25 A study in Mtwara found that the practice of transactional sexual intercourse is sometimes used as a livelihood strategy.40 In addition, findings from Newala district emphasized the role of prostitution in relation to teenage pregnancy.41 Prostitution may be a cause and a result of teenage pregnancies.

Within our study population, nine of 11 teenage girls resigned from school even before their pregnancy commenced. Early school dropout was perceived to be contributing to teenage pregnancy. This conflicts with findings from other studies, which indicate that school dropout is rather a consequence of teenage pregnancies, instead of a contributing factor.1,4,41–43 Previous studies have also shown that lack of reproductive health knowledge is associated with teenage pregnancies.30,37 Therefore, teenage girls might benefit from interventions preventing school dropout. Furthermore, prolongation of education could enable more employment opportunities to interrupt the vicious cycle of poverty.

Lack of community support was mentioned to contribute to teenage pregnancy. In Tanzania, it was previously found that when basic needs are not provided at home, girls are more likely to marry to relieve the economic burden.41 Some parents are forced to bribe their daughters into marriage to receive dowry and escape economic deprivation. This practice has been acknowledged to be related to teenage pregnancies.8,37 Furthermore, cultural norms often preclude open discussion of sexual matters.26 In addition, reproductive health education is often believed to trigger early engagement in sexual activities.25,44 Teenagers whose parents are barely educated are more likely to become pregnant than teenagers whose parents are well educated.37 Lack of education and academic motivation by parents may contribute to early school dropout.45

Findings suggest limited access to contraception. Education has been specified as the cornerstone of pregnancy prevention by the WHO and by many other studies.1,10,11,23,25,30,37 Peer groups are greatly influential in contraceptive use. Research has shown that if teens believe their friends support condom use or actually use condoms, chances are greater that they will actually use condoms.25 This study suggests that educational programs and consistent improvement of current reproductive health education within schools might improve awareness and utilization of contraceptives and knowledge about health and social implications of early pregnancy, leading to a reduction in unintended and intended pregnancies.

LIMITATIONS

Although abortion was mostly not considered to be an option by respondents, traditional medicine and unsafe abortions are known to be widely practiced in Tanzania, especially in rural areas.46,47 It was not within the scope of this study to extensively clarify the extent to which abortion is practiced in this context, but this would be a relevant topic for future research.

The cross-cultural setting with European and Tanzanian researchers of different tribes, socioeconomic classes, and different regions might influence outcomes. The social and politically sensitive nature of topics discussed might have led to socially desirable answers during interviews. This might lead to underestimation of the magnitude of certain contributing factors. Using a compatriot translator contributes to adequacy of translation and to smoothness of conversation including trust building, but subsequently, translation might also end up in establishment of summaries and loss of direct contents of quotations. Last, this study does not provide male perceptions of contributing factors to teenage pregnancies. There remains a lack of empirical evidence concerning the role of men in this matter. Because unequal sexual coercion and dominant male attitude contribute to the incidence of teenage pregnancies, it is critical to involve men in further studies to create a full understanding of the local situation.

CONCLUSION

Through perceptions of teenage girls and local community members, this exploratory study uncovered multiple factors including poverty, school dropout, poor parental support, and insufficient access to contraception contributing to teenage pregnancies. Contributing factors might be dependent on pregnancy being either planned or unplanned. Furthermore, our study has clarified the importance of personality and individual behavior. Despite the limitations and suggested objectives for future research, findings provide new insights into the complex situation of teenage pregnancy in rural southern Tanzania. These insights contribute to a new social theory and therefore enable development of programs by local and national organizations to reduce teenage pregnancies and improve health, social, and educational situations of teenage girls.

DECLARATIONS

Availability of data and materials.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization , 2014. Adolescent Pregnancy Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs364/en/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- 2.Chandra-Mouli V, Camacho AV, Michaud P, 2013. WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. J Adolesc Health 52: 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Republic Of Tanzania - National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) , 2016. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS 2015–2016). Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: National Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neal SE, Chandra-Mouli V, Chou D, 2015. Adolescent first births in East Africa: disaggregating characteristics, trends and determinants . Reprod Health 12: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Republic of Tanzania - National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) , 2017. 2016 Tanzania in Figures. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: National Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Wen SW, Fleming N, Demissie K, Rhoads GG, Walker M, 2007. Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort study . Int J Epidemiol 36: 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganchimeg T, et al. WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal Newborn Health Research Network , 2014. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG 121: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNFPA , 2013. Motherhood in Childhood: Facing the Challenge of Adolescent Pregnancy: The State of World Population 2013. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund, pp. 132, 163–196. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atuyambe L, Mirembe F, Johansson A, Kirumira E, Faxelid E, 2005. Experience of pregnant adolescents—voices from Wakiso district, Uganda . Afr Health Sci 5: 304–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization , 2011. Preventing Early Pregnancy and Poor Reproductive Outcomes among Adolescents in Developing Countries. Available at: http://www.who.int/immunization/hpv/target/preventing_early_pregnancy_and_poor_reproductive_outcomes_who_2006.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization , 2004. Adolescent Pregnancy – Issues in Adolescent Health and Development. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42903/9241591455_eng.pdf;jsessionid=A241CE8C3CDEC96AF1FCFF95DCC385B0?sequence=1. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- 12.Thomson Reuters Foundation , 2013. Documentary: Pregnant at 13, Tanzania’s Child Mothers. Available at: http://news.trust.org//item/20131010165911.wqf1a/. Accessed July 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser BG, Strauss AL, 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, Illinois:Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boeije H, 2016. Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek – Denken en doen (2e druk). Amsterdam, The Nederlands: Boom Uitgevers Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss AL, Corbin J, 2007. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, Agurto S, Winkvist A, 2001. Researching domestic violence agains women: methodological and ethical considerations . Stud Fam Plann 32: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization , 2007. WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Researching, Documenting and Monitoring Sexual Violence in Emergencies . Available at: http://www.who.int/gender/documents/OMS_Ethics&Safety10Aug07.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sathyanarayana Rao T, Nagpal M, Andrade C, 2013. Sexual coercion: time to rise to the challenge . Indian J Psychiatry 55: 211–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshua Project , 2018. Mwera. Available at: https://www.ethnologue.com/language/mwe. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshua Project , 2018. Makonde. Available at: https://www.ethnologue.com/language/kde. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieminen A, 2017. Traditional Unyago Training in Tanzania - A Step to Adolescence or a Leap to Motherhood. Vantaa, Finland: Laurea University of Applied Sciences. Available at: http://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/134948. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jambulosi M, Engdahl H, 2009. Towards a Theology of Inculturation and Transformation: Theological Reflections on the Practice of Initiation Rites in Masasi District in Tanzania. Cape Town, South Africa: University of the Western Cape. Available at: http://etd.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11394/3223. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mbonile L, Kayombo EJ, 2008. Assessing acceptability of parents/guardians of adolescents towards introduction of sex and reproductive health education in schools at Kinondoni municipal in Dar es Salaam city. East Afr J Public Health 5: 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girls Not Brides , 2017. Child Marriage Around the World: Tanzania. Available at: https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/child-marriage/tanzania/#stats-references. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunor H, 2015. School Based Reproductive Health Education Programmes and Teenage Pregnancy in Mtwara Region, Tanzania. Morogoro, Tanzania: Dissertation for the Degree of Master of Arts in Rural Development of Sokoine University of Agriculture. Available at: http://www.suaire.suanet.ac.tz:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/793/HAWA%20DUNOR.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith K, Coleman S, 2012. Evaluation of Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Approaches: Design of the Impact Study. Mathematica Policy Research. Available at: https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/evaluation-of-adolescent-pregnancy-prevention-approaches-design-of-the-impact-study. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makundi PE, 2010. Factors Contributing to High Rate of Teen Pregnancy. A Study of Mtwara MA. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Dissertation for Award of Muhimbili University of Health and Applied Sciences, 51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.UNFPA , 2009. Adolescents Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings: A Companion to the Inter Agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund, 92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss E, Whelan D, Gupta GR, 2000. Gender, sexuality and HIV: making a difference in the lives of young women in developing countries . Sex Relationship Ther 153: 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maly C, et al. 2017. Perceptions of adolescent pregnancy among teenage girls in Rakai, Uganda . Glob Qual Nurs Res 4: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cubbins L, Jordan L, Nsimba S, 2014. Tanzanian men’s gender attitudes, HIV knowledge, and risk behaviours . Etude Popul Afr 28: 1171–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muhanguzi FK, 2011. Gender and sexual vulnerability of young women in Africa: experiences of young girls in secondary schools in Uganda. Cult Health Sex 13: 713–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagman J, Baumgartner JN, Geary CW, Nakyanjo N, Ddaaki WG, Serwadda D, Wawer MJ, 2009. Experiences of sexual coercion among adolescent women: qualitative findings from Rakai District, Uganda . J Interpersonal Violence 24: 2073–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services , 2016. Engaging Adolescent Males in Prevention. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/adolescent-development/reproductive-healthand-teen-pregnancy/teen-pregnancy-and-childbearing/engaging-adolescent-males-in-prevention/index.html. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jewkes R, Morrell R, Christofides N, 2009. Empowering teenagers to prevent pregnancy: lessons from South Africa. Cult Health Sex 11: 675–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erhardt S, Leichweiß S, Temu A, 2011. Critical Gender Issues in Mtwara Region Tanzania. German, Tanzania: Tanzanian German Programme to Support Health, 50. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunor H, Urassa J, 2017. Access to reproductive health services and factors contributing to teenage pregnancy in Mtwara region, Tanzania. Develop Country Stud 7: 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munir K, 2012. Temptations, Desire and Adolescence: a Need Assessment of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Life Skills of Youth in Mtwara Region, Tanzania. Bordeux, France: Thesis for Award of Master Degree at University of Segalen, 90. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siettou M, Sarid M, 2011. Risk factors of teenage pregnancy. J Vina TouAsklipiou 10: 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bangser M, 2010. Falling through the Cracks’ Adolescent Girls in Tanzania: Insights from Mtwara. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development, 21. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCleary-Sills J, Doughlas Z, Rwehumbiza A, Hamisi A, Mabala R, 2013. Gendered norms, sexual exploitation and adolescent pregnancy in rural Tanzania. J Reprod Health Matters 20: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Bank , 2017. Economic Impacts of Child Marriage: Global Synthesis Report. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530891498511398503/pdf/116829-WP-P151842-PUBLIC-EICM-Global-Conference-Edition-June-27.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lugonzo HM, Chege F, Wawire V, 2017. Factors contributing to the high drop out of girls in the secondary schools around lake Victoria: a case study of Nyangoma Division in Siaya County, Kenya. Greener J Educ Res 7: 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markham CM, Tortolero SRS, Escobar- Chaves L, Parcel GS, Harrist R, Robert CA, 2003. Family connectedness and Sexual risk-taking among urban youth attending alternative high schools. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 35: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenberg M, et al. 2015. Relationship between school dropout and teen pregnancy among rural South African young women. Int J Epidemiol 44: 928–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liwa A, et al. 2017. Herbal and alternative medicine use in Tanzanian adults admitted with hypertension related diseases. A mixed methods study. Int J Hypertens 2017: 5692572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penfold S, et al. 2010. A large cross-sectional community-based Study of newborn care practices in Southern Tanzania. PLoS One 5: e15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.