ABSTRACT

Onchocerciasis, caused by infection with Onchocerca volvulus, has been targeted for elimination by 2030. Currently, onchocerciasis elimination programs rely primarily on mass distribution of ivermectin. However, ivermectin alone may not be sufficient to achieve elimination in some circumstances, and additional tools may be needed. Vector control has been used as a tool to control onchocerciasis, but vector control using insecticides is expensive and ecologically detrimental. Community-directed removal of the trailing vegetation black fly larval attachment sites (slash and clear) has been shown to dramatically reduce vector biting densities. Here, we report studies to optimize the slash and clear process. Conducting slash and clear interventions at Simulium damnosum sensu stricto breeding sites located within 2 km of afflicted communities resulted in a 95% reduction in vector biting. Extending slash and clear further than 2 km resulted in no further decrease. A single intervention conducted at the first half of the rainy season resulted in a 97% reduction in biting rate, whereas an intervention conducted at the end of the rainy season resulted in a 94% reduction. Vector numbers in any of the intervention villages did not fully recover by the start of the following rainy season. These results suggest that slash and clear may offer an inexpensive and effective way to augment ivermectin distribution in the effort to eliminate onchocerciasis in Africa.

INTRODUCTION

The threat of infection with Onchocerca volvulus, the causative agent of river blindness, remains after decades of efforts to control and eliminate this parasite in foci and endemic zones in both hemispheres. Following a large-scale control program that targeted Simulium damnosum sensu lato, the black fly vectors in West Africa,1 national and regional efforts over the past three decades have been devoted to addressing this vector-borne disease mainly through mass drug administration (MDA) with ivermectin, or Mectizan® (Merck & Co, Inc. Kenilworth, NJ). The results, although encouraging in the Americas and some locations in Africa, indicate that complete success will likely require decades of effort to achieve control and eventual elimination of the parasite.2

Several epidemiological models predict that elimination of parasite transmission by 2030, a major goal of the WHO,3 is likely feasible in low- to moderate-endemic settings if long-term treatment coverage rates equal or exceed 75% of eligible persons.4 However, in some situations—areas/countries where initial endemicity of the parasite was quite high, MDA coverage rates have fallen below guidelines or have yet to begin—these models indicate that different approaches will be needed. These could include expanding the frequency of the ivermectin drug regimen to two and even four times a year, adding new drugs that are either longer lasting than ivermectin or immediately macrofilaricidal, or implementing vector control where possible.5,6

Onchocerca volvulus transmission in Uganda has historically been associated with two major taxa—Simulium neavei, the main vector in the country, and several members of the S. damnosum species complex. The latter include Simulium kilibanum, formerly a vector in several foci in western Uganda,7 and two savanna cytospecies, S. damnosum sensu stricto and Simulium sirbanum.8,9 Local control of vector black flies (S. neavei) has been used in conjunction with twice per year ivermectin MDA to rapidly achieve suppression and interruption of transmission in several foci in Uganda.10–16 This has been achieved using insecticides delivered through a regimented, vertical program. However, to be successful and sustainable the long term, control efforts will have to be affordable and less reliant on structured government programs. As a possible paradigm for the way forward, the success of community-directed ivermectin treatment, which employs local village volunteers to dispense the drug, suggests that this strategy could also work for vector control.

A recent study in Uganda showed that removal of aquatic vegetation, the attachment sites for blackfly larvae and pupae, by minimally trained villagers, reduced biting rates by local populations of S. damnosum s. str. by 89–99% for up to 120 days.17 This approach, termed “slash and clear,” was well received by local participants, suggesting a likely willingness by communities to implement and sustain this effort. To determine the best time for aquatic vegetation removal to deter peak vector activity as well as the distance from a community that breeding sites would need to be cleared of vegetation, we designed a series of studies aimed at determining these key factors over a 1-year period and a distance of up to 3 km.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of study sites.

This study was conducted in Amuru district located in Northern Uganda within the Madi-mid North focus of onchocerciasis (Figure 1). The district has a population of 178,000 people according to the national population and housing census of 2014 conducted by Uganda Bureau of Statistics.18 The climate of Amuru consists of dry and wet seasons, with 1,500 mm average total rainfall received per annum. Normally, the wet season extends from April to October with peaks in May and August, whereas the dry season begins in November and extends up to March. The vegetation of Amuru consists of intermediate savanna grassland.19 The common grasses include Imperata cylindrica, Haperrhenia rufa, and Digitaria scalarum, and some of these grass species are common in and along the rivers. The main river in Amuru district is the Unyama, which flows northward and joins the River Nile in Nimule, South Sudan. The Unyama was chosen for the “slash and clear” study because of its suitability in terms of its size and flow. The vector of O. volvulus in this region is the savannah dwelling species, S. damnosum s. str. (R. Post personal communication). The Unyama is one of the perennial rivers in the Albert Nile River Basin. It originates from Bar Olam village, Unyama subcounty in Gulu district and has an average width of 15 m and a total length of 107 km from the source to the point where it joins the Nile in South Sudan. The river bed is generally sandy and rocky with some portions characterized by large layers of rocks with fast flowing waters that provide conducive ecological habitat for S. damnosum s. str. breeding. Areas with suitable breeding habitat constitute a stretch of about 71 km between Otong village in Pabo subcounty and Elegu in Atiak subcounty. The mean river discharge during the dry season is 6.7 m3/second. In the rainy season, the mean flow is 28.7 m3/second with a yearly mean of 17.7 m3/second.20 The Unyama is smaller (with a catchment area of 1,574 km2) than the largest Nile tributary in the area, the Aswa river (with a catchment area of 2,666 km2) which is located approximately 23 km to the east.20

Figure 1.

Location of study communities. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

As a first step in identifying study villages, potential S. damnosum s. str. breeding sites were identified by remote sensing as previously described.17,21 Villages were selected for potential inclusion in the study if they were located within 1 km of a predicted breeding site and were separated by at least 15 km from any other village selected for potential inclusion.

The communities selected for potential inclusion in the study were each visited by the field team. Team members questioned the residents of the village in the local language (Acholi) about their knowledge of biting black flies, helping to determine if the flies represented a significant nuisance. Predicted breeding sites were then validated by ground prospection to confirm the presence of S. damnosum s. str. larvae. Communities where the residents reported a significant nuisance from the biting flies and where the predicted breeding sites were validated by ground prospection were enrolled in the study. The communities chosen for the study and the distances to the Unyama and Aswa (the major rivers in the area) are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distance of study villages to Unyama and Aswa rivers

| Village | Distance from River Unyama (km) | Distance from River Aswa (km) |

|---|---|---|

| Abongorwot | 0.72 | 17.6 |

| Bajere | 0.73 | 12.30 |

| Elegu A | 0.66 | 13.20 |

| Gulo Kano | 0.91 | 21.90 |

| Gunya | 0.98 | 10.4 |

| Elegu B | 0.89 | 12.30 |

| Kalawal | 0.57 | 13.02 |

| Makenge | 0.90 | 18.9 |

| Okidi Central | 0.94 | 12.40 |

| Otong | 0.93 | 27.1 |

| Palapil | 0.73 | 13.70 |

| Patilei | 0.91 | 14.6 |

| Pwomunu | 0.72 | 17.5 |

Catching sites close to the river were established either along the bank of the river close to the community or in an open and not densely shaded site near the river. Sites within the communities were chosen by identifying places that were commonly frequented by community members where residents reported flies were a nuisance. All catch sites were separated from crowded river crossings and laundry sites by at least 50 m.

Implementation of the slash and clear technique and subsequent monitoring.

Baseline fly collections were carried out for 1 week before any interventions, using standard human landing collection (HLC) techniques. Following the baseline collections, young men (16–22 years of age) were recruited to carry out slash and clear in the river near the intervention villages. The recruits were brought to the breeding sites located upstream and downstream of the village and were instructed in the process of cutting the trailing vegetation from the water and throwing it on the river bank to dry, thereby killing the adherent fly larvae and pupae. Fly collections were carried out twice per week after the interventions for the duration of each study.

Distance optimization trials.

Two trials were conducted to assess the maximal distance that slash and clear needed to be carried out to reduce vector biting densities. In the first trial, a total of six villages with high biting rates were identified. The villages were randomly assigned into control and intervention arms, and fly collections were carried out daily from August 3, 2018 through August 10, 2018 at the designated catch sites to determine the baseline biting rate. Slash and clear activities were then carried out at the intervention sites from August 12, 2018 through August 15, 2018, removing the trailing vegetation from all breeding sites located 0–1 km upstream and downstream from the point on the river closest to the community. Fly collections were then carried out until September 10, 2018, at which point breeding sites 1–2 km upstream and downstream from intervention villages were cleared. The second slash and clear interventions were carried out from September 11 through September 14, 2018. Collections were carried out for approximately another month, at which point the breeding sites located 2–3 km upstream and downstream from the intervention villages were cleared on October 11, 2018 through October 20, 2018. Flies were collected until February 18, 2019, or until 200 days had elapsed since the start of the trial. Collections were carried out twice per week at all sites throughout the trial period, but no interventions were conducted at the control villages.

The design of the second study was similar to the first, except that two HLC teams were used at all villages (one at the standard catch site near the river and one in the community) to monitor biting densities both along the rivers and within the communities. In addition, by the time we instituted the second trial, news of the effectiveness of the slash and clear intervention had spread throughout the study area, and residents of villages who had not been included in the earlier trials were approaching the research team and asking to have the slash and clear program initiated in their communities as well. As a result, we felt it to be unethical to withhold the intervention from any more communities than was absolutely necessary. For this reason, instead of a matched number of intervention and control villages, a single village (Pwomunu) was designated as the control, and all other villages were designated for interventions. The second trial began on June 3, 2019 with daily baseline collections conducted in all communities at both the river and community catch sites. Slash and clear activities were then carried out at breeding sites located 0–1 km upstream and downstream from the point of the river closest to the community in the intervention villages beginning on June 14, 2019. Slash activities were suspended from June 15, 2019 through June 20, 2019 because of heavy rains that made it too dangerous to enter the rivers. Slash activities resumed on June 21, 2019 and were completed on June 23, 2019. The second slash (at breeding sites 1–2 km upstream and downstream from the intervention villages) was carried out on July 28–30, 2019, and the third slash (at breeding sites 2–3 km upstream and downstream from the intervention villages) was performed on September 4–6, 2019. Fly collections continued at twice per week intervals at all sites through the end of the study on December 7, 2019.

Determining the optimal timing and frequency of slash and clear treatments.

To investigate the optimal timing and frequency of the slash intervention, a long-term study (1 year study) was designed. This study involved a total of six intervention villages and a single control village (Pwomunu, the same control village used in the study described earlier). The blackfly landing rate in all communities was initially monitored daily for 7 days (June 3–9, 2019). In four of the intervention villages, a single slash intervention was carried out from June 13 to 23, 2019, removing the trailing vegetation at all breeding sites within 3 km upstream and downstream of the point on the river closest to each community. Landing rates were then monitored twice per week. In November, at the end of the rainy season, a second slash intervention was carried out in four villages, extending from November 14 to 18, 2019. Two of these villages had not received a slash intervention in June, whereas two had been included in the June intervention. Thus, at the end of the November 2019 slash intervention, the intervention villages were divided into three categories: two communities that received a slash intervention in June 2019, two that received the intervention in November 2019, and two that received interventions in both June 2019 and in November 2019. No interventions were carried out at the control village. Landing rates were monitored twice per week in all villages until the end of May 2020, resulting in a full year of observations.

Data analysis.

Monthly biting rates (MBRs) were calculated as the geometric mean of the number of flies collected during the month times the number of days in the month, as previously described.22 The significance of the differences in the fly collections among the different groups was evaluated using a t-test.

Ethical clearance.

The experiments described here were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the Uganda Vector Control Division (approval REF/VCDREC/071) and the University of South Florida (approval CR3_Pro00015108). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All individuals participating in the study received ivermectin twice per year as part of the routine mass drug distribution program active in this area administered by the Ugandan Ministry of Health.

RESULTS

Slash distance optimization trials.

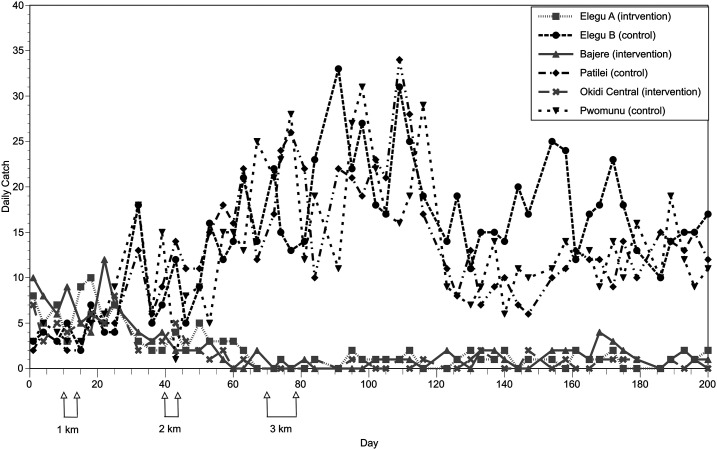

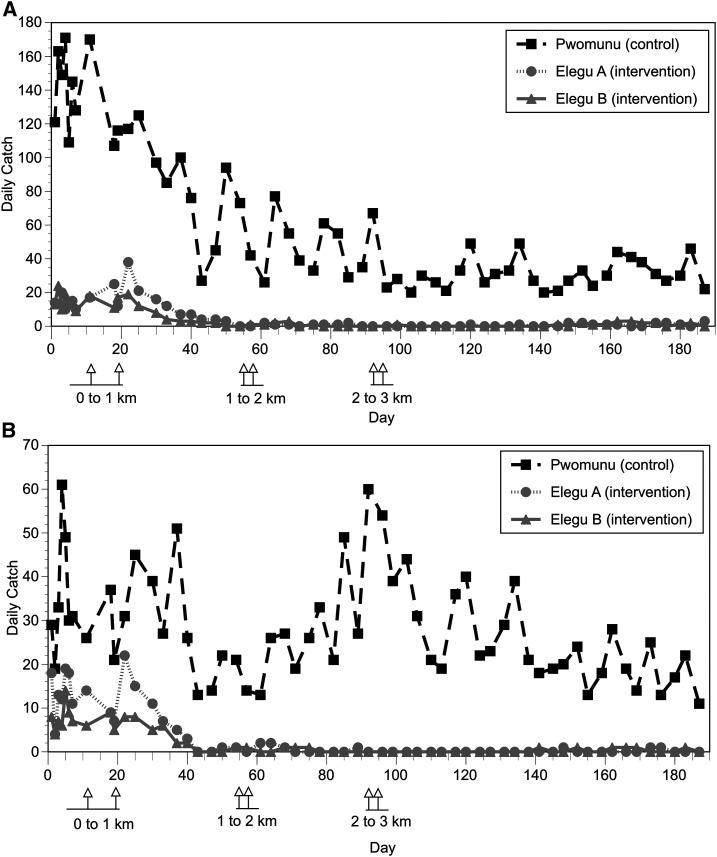

Previous studies indicated that a single intervention of slash and clear where the trailing vegetation was removed from S. damnosum s. str. breeding sites resulted in a dramatic reduction in the biting rate (ca. 90%), with the maximum effect reached approximately 20 days following the vegetation clearance.17 To investigate the minimal distance that was necessary to clear the vegetation to obtain the maximum reduction in the biting rate, two trials were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. In the first trial, involving three control and three intervention villages, the number of flies caught at the intervention villages was observed to decline to roughly half of those seen before the intervention in the test villages 3 weeks after the first slash (cutting the vegetation at breeding sites located 0–1 km from the village), whereas the number of flies caught in the control villages increased (Figure 2). A second decline in the numbers of flies caught (almost to zero) was observed to occur approximately 3 weeks following the second slash (clearing vegetation from the breeding sites 1–2 km from the villages), whereas little additional effect was seen following the final slash (clearing vegetation from the breeding sites 2–3 km from the villages; Figure 2). To quantify the effect of each slash treatment, the average daily biting rate for a period spanning approximately 3–6 weeks following each slash treatment was calculated for each intervention village. This 3- to 6-week post-intervention period was chosen because in this study and in previous studies17 it took roughly 3 weeks for the maximum effect of a slash treatment to be seen in the number of adult flies. This is because removing the trailing vegetation at the breeding sites targets the aquatic stages of the fly’s life cycle and not the adults. These averages were then normalized to the means of the average biting rates from the control villages from the same periods. This was carried out because the baseline biting density varied among communities because of differences in the size, number, and productivity of the breeding sites located near each village, and because fly densities also varied over time, due to weather conditions in the study area. When normalized in this fashion, the first treatment (slashing 0–1 km from a village) resulted in an average 82% reduction in the biting rate 21–42 days after treatment (P < 0.001; t-test; Figure 3). The second treatment (slashing 1–2 km from the villages) resulted in an overall 99% reduction in the biting rate, which was a significant improvement over the effect of the first treatment (P < 0.001; t-test; Figure 3). In all intervention communities, slashing the breeding sites located 0–2 km of the communities reduced the mean daily biting rate to less than 1 bite/day (Figure 3). Extending the slash treatment to 2–3 km from the communities did not further reduce the biting rate (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Daily landing catches observed in the first slash and clear distance optimization trial. Intervention communities are shown in gray and control communities in black. Flies were collected twice per week in each village.

Figure 3.

Normalized average daily biting rates (DBRs) before and after each intervention in the first slash and clear distance optimization trial. Average DBRs were calculated from the data presented in Figure 2 for the period 3–6 weeks after each intervention, and then normalized to the average DBR from the same period in the control villages, as described in the text.

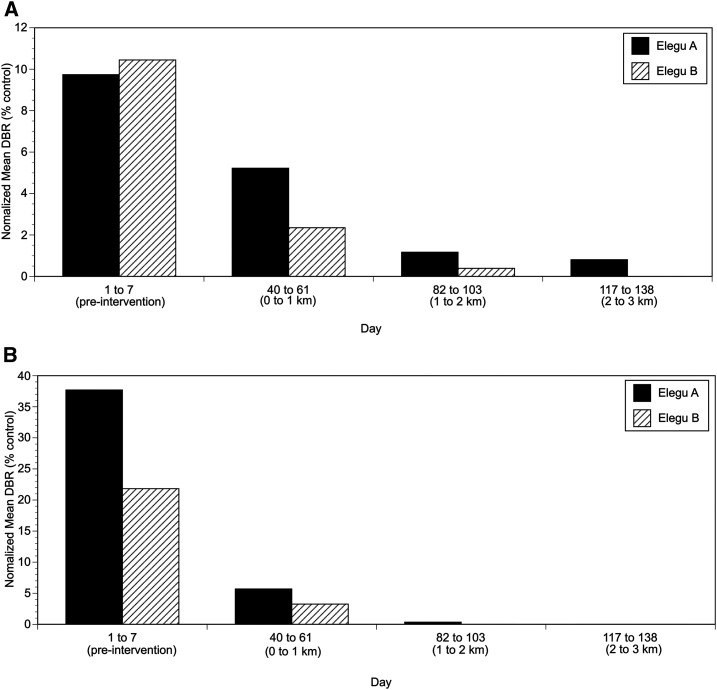

In the initial experiment evaluating the minimal distance necessary to reduce the biting rate, flies were collected at previously established collection sites located near the river. It was therefore possible that this would not reflect the actual reductions in the community, which were located farther from the river, and therefore might also be invaded by flies that had traveled from more distant breeding sites. To determine if this was the case, the slash by distance experiment was repeated as described in Materials and Methods, this time stationing collectors both along the river as before and also in the community. The results of the second slash by distance trial are shown in Figure 4, whereas the 3- to 6-week post-intervention mean daily biting rates (normalized to the mean biting rates in the control village) are shown in Figure 5. In this trial, the first slash treatment (slashing breeding sites 0–1 km upstream and downstream from the intervention villages) reduced the biting rate at the river catch sites by an average of 62% (Figures 4 and 5, panels A; P < 0.001; t-test) whereas the biting rate in the communities was reduced by an average of 85% (Figures 4 and 5, panels B; P < 0.001; t-test). Following the second treatment (slashing breeding sites 1–2 km upstream and downstream from the intervention villages), the average biting rate was further reduced by an average of 92% at the river catch sites and an average of 99% in the communities. The difference between the number of flies caught after the first and second slash treatments in the villages was not statistically significant. However, this may be due to the fact that very few flies were collected in either intervention village following the first treatment (average daily biting rate in Elegu A after the first treatment = 1.0; average biting rate in Elegu B after the first treatment = 0.57). As was seen in the first trial, extending the treatments to 2–3 km upstream and downstream from the village did not result in a significant reduction in the biting rate over what was seen after the second (1–2 km) treatment (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Daily landing catches observed in the second slash and clear distance optimization trial. (A) Daily catches at the collection sites adjacent to the river. (B) Daily catches at the collection sites in the community. In each panel, intervention communities are shown in gray and the control community is in black. Flies were collected twice per week in each village.

Figure 5.

Normalized average daily biting rates (DBRs) before and after each intervention in the second slash and clear distance optimization trial. Average DBRs were calculated from the data presented in Figure 4 for the period 3–6 weeks after each intervention and then normalized to the average DBR from the same period in the control village, as described in the text. (A) Normalized DBRs at the collection sites adjacent to the river. (B) Normalized DBRs at the collection sites in the community.

Optimal timing and frequency of slash and clear treatments.

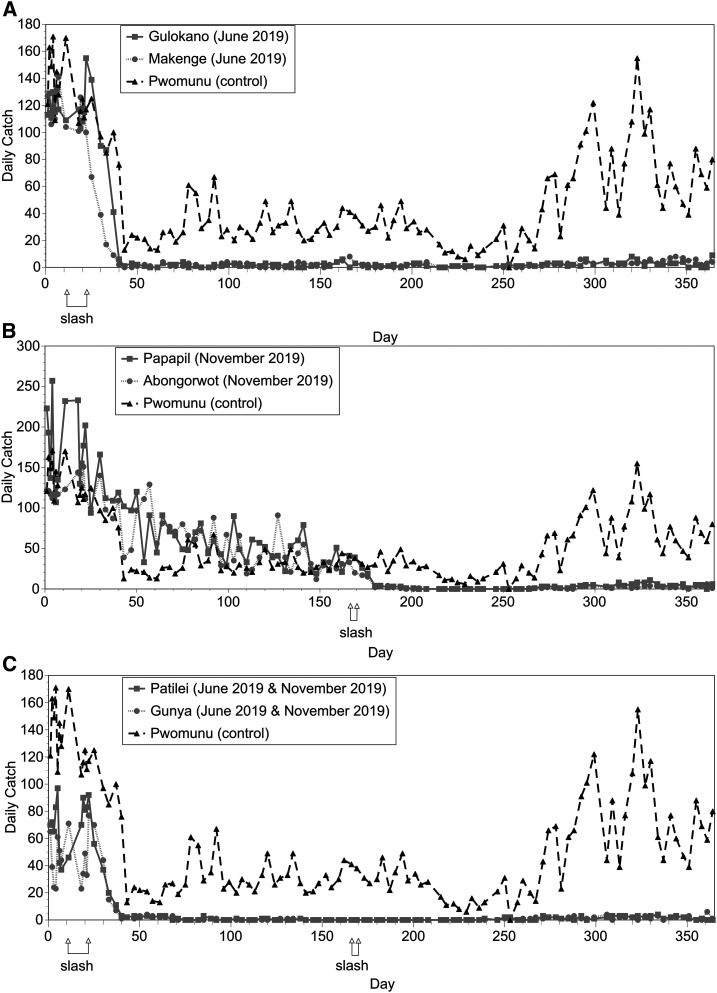

To investigate the optimal timing and frequency of slash and clear interventions, a long-term study was designed as described in Materials and Methods. Consistent with our previous studies, an initial slash intervention in June 2019 resulted in a dramatic reduction in landing rates (Figure 6). On average, the landing rates in the villages receiving the June 2019 slash interventions were reduced by 97% on day 50 (28 days following the intervention) compared with pre-intervention levels (Figure 6A and C). In the two intervention villages that did not receive a slash treatment in June 2019, the landing rate declined gradually from June 2019 to November 2019 in parallel with what was observed in the control village (Figure 6B). This pattern was expected, as fly densities in this area vary throughout the year, peaking in the rainy season and reaching a nadir during the dry season in December through February.17 Following the slash intervention in these villages in November 2019, the landing rate was reduced by 94% 24 days after the intervention when compared with the mean landing rate for the 2 weeks before the November 2019 intervention (Figure 6B). No additional reduction in the biting rate was seen as a result of the November 2019 intervention in the two villages that had already received a slash intervention in June 2019 (Figure 6C). However, very few flies were present at these sites before the November 2019 intervention, as the landing rate had been already dramatically reduced by the June 2019 treatment. In the two villages receiving slash interventions in both June 2019 and November 2019, the MBRs averaged less than 2 bites/month in October 2019 (before the second intervention), suggesting that there were very few flies left to eliminate with the second intervention at these sites (Table 2). At the end of the study in May 2020, MBRs remained low in all intervention villages, representing an average 98.6% reduction in the pre-intervention rates measured in June 2019 (Table 2; P < 0.0001; t-test). The landing rates in May 2020 were not significantly different between the villages that received single slash interventions in June 2019 or November 2019 (P = 0.5; t-test). However, the landing rates in May 2020 in the two villages that received slash interventions in both June 2019 and November 2019 were significantly lower than those in the villages that had gotten a single slash treatment (P < 0.01; t test).

Figure 6.

Effect and duration of slash and clear interventions conducted early and late in the rainy season. (A) Effect of a single intervention conducted in June 2019. (B) Effect of a single intervention conducted in November 2019. (C) Effect of two interventions conducted in June 2019 and November 2019. In each panel, intervention communities are shown in gray, and the control community is in black. Flies were collected twice per week in each village.

Table 2.

Monthly biting rates before slash interventions and at the end of the study

| Village | Intervention date | Pre-slash June 2019 | October 2019 | May 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gul Okano | June 2019 | 637.4 | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| Makenge | June 2019 | 645.5 | 4.5 | 15.6 |

| Palapil | November 2019 | 840.3 | 146.3 | 12.2 |

| Abongorwot | November 2019 | 624.8 | 139.8 | 6.2 |

| Patilei | June and November 2019 | 335.2 | 0.4 | 4.6 |

| Gunya | June and November 2019 | 216.6 | 1.6 | 3.5 |

| Pwomunu | None | 736.2 | 109.4 | 181.6 |

DISCUSSION

The results presented here reinforce those in our previous publication17 that demonstrated that reduction of larval attachment sites by removal of trailing vegetation (slash and clear) can dramatically reduce the biting rate of S. damnosum s. str., one of the most important vectors of O. volvulus in Africa. This method is simple and inexpensive to perform, requiring equipment commonly found in the communities of rural Africa (e.g., machetes and rubber boots). Local residents can be recruited to carry out the vegetation removal in the rivers and streams, minimizing labor costs.

In our initial trials of slash and clear, breeding sites up to 3 km from the communities were targeted for clearing. As the banks of many rivers and streams in Africa are covered with thick vegetation, movement along the streams can be difficult, and minimizing the distance needed to achieve an optimal reduction in the biting rate is very desirable. The results reported here demonstrate that although a substantial reduction in biting rate is achieved by clearing the breeding sites within 1 km of a village, the maximum effect is achieved when breeding sites within 2 km of the villages are cleared. Clearing the breeding sites 2–3 km from the village resulted in no further reductions in the biting rate. Thus, restricting the slash and clear activities to breeding sites within 2 km of a community appeared to be sufficient.

In our previous study, and in the initial studies reported here, we conducted our fly collections at traditionally productive sites near the breeding habitat. It was possible that the flies biting residents in the communities themselves might be also coming from more distant breeding sites, and therefore the reductions in the village might be less dramatic than what was observed at the traditional catch sites. To determine if this was the case, we placed collection teams both at the traditional catch sites and sites within the community. We observed reductions in the biting rate in the community that were very similar to those seen at the traditional catch sites. The differential dispersal behavior by adult blackflies, particularly savanna sibling species in the S. damnosum complex such as S. damnosum s. str., is well known.23,24 Nulliparous flies tend to move away from their riverine breeding sites in search of blood meals, whereas parous flies remain close to or move along the rivers after oviposition. This is particularly true for older parous flies which have a higher O. volvulus transmission potential. Thus, the area most pronounced for transmission is usually less than a kilometer from rivers and streams.25 Although we did not evaluate flies for parity as part of this study, it is apparent that slash and clear had a profound effect on host-seeking flies both in the area where O. volvulus transmission was most likely to occur and in the villages themselves.

The duration of the slash and clear effect was quite long-lasting. Villages subjected to a single intervention in June 2019 had biting rates that were less than 5% of those seen before the intervention as late as May 2020. Similar reductions were observed in May 2020 in villages where a single intervention was carried out in November 2019. This is perhaps not surprising, as once the vegetation is cleared from a site, we have observed that its regrowth is quite slow. During periodic visits to the intervention communities, we have observed that the grasses that trail into the river took at least 6 months to recover from a slash treatment, whereas the heavier trailing growth (e.g., tree branches) had not recovered 1 year following the slash treatment.

At the end of the study to investigate the optimal timing of the slash and clear interventions, the MBRs in the communities that were treated in both June 2019 and November 2019 were significantly less than those in the communities that were treated only once, in either June 2019 or November 2019. However, it is not clear that this difference is of any practical importance. In all the intervention villages regardless of the timing of the slash intervention, the biting rates at the end of the study were reduced by more than 90% compared with either the pre-intervention levels or with the level observed in the control village at the end of this study. It is likely that this level of reduction in biting would have resulted in a corresponding reduction in the nuisance experienced by the community and in parasite transmission. It is therefore likely that from a practical point of view, a single annual intervention at a time chosen as most convenient by the communities will be sufficient to realize the goal of dramatically reducing the biting rate over the long term.

Our experience during these experiments has also made us optimistic that, once communities are instructed how to carry out slash and clear and they see the effect it has on the population of biting blackflies, they should be able to sustain this on their own. During the course of our initial experiments, we were approached by members of our control communities and nearby communities requesting that we institute a slash and clear program in their communities as well. Apparently, word of the success of the program had spread, and these communities wanted to become involved. For this reason, we felt ethically bound to limit the number of control communities to one in the 2019 trials. Given that slash and clear is simple to perform and uses materials generally available to the residents of the afflicted communities, we feel that, once instructed how to do so, the communities themselves will be motivated to carry out further interventions on their own as the fly populations become a nuisance once again.

Reducing the annual biting rate by slash and clear over a significant time period should greatly impact local O. volvulus populations. For example, Duerr and Eichner26 estimated that a threshold biting rate ≤ 730 bites per person per year would eventually lead to the elimination of savannah onchocerciasis. The results presented here show that threshold may be easily achievable using slash and clear. More recently, a model using data from a single slash and clear effort combined with ivermectin MDA predicted that the two approaches when combined would contribute to a rapidly falling parasite population, ultimately saving up to 20 years of effort toward elimination if slash and clear were also to be implemented on a monthly basis.6 Our results reported here indicate that one to two interventions essentially eliminated the local vector population for a year, thus obviating the need for monthly interventions.

The use of ivermectin as a long-term monotherapy has raised concerns regarding the possibility of the development of resistance.27–29 One of the recommendations to expedite control and reach target elimination dates by 2030 is to increase the frequency of treatment from once a year to two and even four treatments per year.4 Studies in Ghana and elsewhere have reported the occurrence of suboptimal responders, in which microfilariae appeared in the skin more rapidly than expected following a single ivermectin treatment.30 Although this occurred in a small segment of the population, this finding suggested that over time, selection of local populations by drug pressure might favor the emergence of O. volvulus strains resistant to ivermectin.30 Because of the immediate and relatively long-term effect of slash and clear on the biting rate, this method would likely have an ameliorating effect on parasite gene flow, thereby avoiding selection pressure and creating long time gaps between the appearance of adult worms.

Altough the slash and clear interventions were very successful in the S. damnosum s. str. infested streams of Northern Uganda, it is possible that this method may not be generally applicable in all areas of Africa. For example, in the forests of Central and West Africa, the forest-dwelling sibling species of S. damnosum s. l. breed in small, very abundant, streams. In this habitat, it may be difficult or impossible to identify and clear all the breeding sites within 2 km of a given community. Similarly, in some parts of Africa, S. damnosum s. l. larvae may attach to rocks in the streambed as well as to the trailing vegetation along the bank.31 In this situation, clearing the vegetation may have little effect on the immature population. Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of slash and clear in these regions. If it is found that slash and clear is not capable of significantly reducing the vector rate in these areas, alternative means of community based control, such as the Esperanza window trap,32 might be an effective alternative.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the residents of the study villages in Amuru district for welcoming us into their communities and assisting us with this project and the subcounty supervisors, site supervisors, and vector collectors for their efforts during this study. We also thank Rory Post for sharing the results of his cytotaxonomic identification of the flies of the River Unyama before publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boatin B, 2008. The onchocerciasis control programme in west Africa (OCP). Ann Trop Med Parasitol 102 (Suppl 1): 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stolk WA, Walker M, Coffeng LE, Basanez MG, de Vlas SJ, 2015. Required duration of mass ivermectin treatment for onchocerciasis elimination in Africa: a comparative modelling analysis. Parasit Vect 8: 552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization , 2020. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo. Accessed July 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization , 2019. The World Health Organization 2030 goals for onchocerciasis: insights and perspectives from mathematical modeling: NTD Modelling Consortium Onchocerciasis Group. Gates Open Res 3: 1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verver S, et al. 2018. How can onchocerciasis elimination in Africa be accelerated? Modeling the impact of increased ivermectin treatment frequency and complementary vector control. Clin Infect Dis 66: S267–S274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith ME, et al. 2019. Accelerating river blindness elimination by supplementing MDA with a vegetation “slash and clear” vector control strategy: a data-driven modeling analysis. Sci Rep 9: 15274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruger A, Nurmi V, Yocha J, Kipp W, Rubaale T, Garms R, 1999. The Simulium damnosum complex in western Uganda and its role as a vector of Onchocerca volvulus. Trop Med Int Health 4: 819–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunbar RW, 1966. Four sibling species included in Simulium damnosum Theobald (Diptera: Simuliidae) from Uganda. Nature 209: 597–599. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosskey RW, Howard TM, 1996. A New Taxonomic and Geographic Inventory of World Blackflies (Diptera: Simuliidae). London, United Kingdom: Natural History Museum. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katabarwa M, et al. 2012. Transmission of onchocerciasis in Wadelai focus of northwestern Uganda has been interrupted and the disease eliminated. J Parasitol Res 2012: 748540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katabarwa M, et al. 2014. Transmission of Onchocerca volvulus by Simulium neavei in Mount Elgon focus of eastern Uganda has been interrupted. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90: 1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakwo TL, et al. 2015. Successful interruption of the transmission of Onchocerca volvulus in Mpamba-Nkusi focus, Kibaale district, mid-western Uganda. East Afr Med J 92: 401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakwo T, et al. 2017. Interruption of the transmission of Onchocerca volvulus in the Kashoya-Kitomi focus, western Uganda by long-term ivermectin treatment and elimination of the vector Simulium neavei by larviciding. Acta Trop 167: 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luroni LT, et al. 2017. The interruption of Onchocerca volvulus and Wuchereria bancrofti transmission by integrated chemotherapy in the Obongi focus, north western Uganda. PLoS One 12: e0189306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katabarwa M, et al. 2020. Elimination of Simulium neavei transmitted onchocerciasis in Wambabya-Rwamarongo focus of western Uganda Am J Trop Med Hyg 103: 1135–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katabarwa M, et al. 2020. The Galabat-Metema cross-border onchocerciasis focus: the first coordinated interruption of onchocerciasis transmission in Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14: e0007830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacob BG, Loum D, Lakwo TL, Katholi CR, Habomugisha P, Byamukama E, Tukahebwa E, Cupp EW, Unnasch TR, 2018. Community-directed vector control to supplement mass drug distribution for onchocerciasis elimination in the Madi mid-north focus of northern Uganda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uganda National Bureau of Statistics , 2020. National Population and Housing Census- Uganda National Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), 2014. Available at: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/.../sources/census/../Uganda/UGA-2016-05-23.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langlands BW, Jackson RT, Mbakyenga SK, 1974. Soil Productivity and Land Availability Studies for Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Department of Geography, Makerere University, 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Water and The Environment , 2020. Upper Nile Water Management Zone (UNWMZ): Water Resources Development and Management Strategy and Action Plan. Available at: https://www.mwe.go.ug/sites/default/files/library/UNWMZ%20Strategy%20%26%20Action%20Plan.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacob BG, Novak RJ, Toe L, Sanfo M, Griffith DA, Lakwo TL, Habomugisha P, Katabarwa MN, Unnasch TR, 2013. Validation of a remote sensing model to identify Simulium damnosum s.l. breeding sites in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez-Perez MA, Lutzow-Steiner MA, Segura-Cabrera A, Lizarazo-Ortega C, Dominguez-Vazquez A, Sauerbrey M, Richards F, Jr., Unnasch TR, Hassan HK, Hernandez-Hernandez R, 2008. Rapid suppression of Onchocerca volvulus transmission in two communities of the southern Chiapas focus, Mexico, achieved by quarterly treatments with Mectizan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 79: 239–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Berre R, 1966. Contribution a l’etude biologique et ecologique de Simulium damnosum Theobald, 1903 Simuliid. Mem ORSTOM 17: 204. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duke BO, 1975. The differential dispersal of nulliparous and parous Simulium damnosum. Tropenmed Parasitol 26: 88–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renz A, Wenk P, 1987. Studies on the dynamics of transmission of onchocerciasis in a Sudan-savanna area of north Cameroon I. Prevailing Simulium vectors, their biting rates and age-composition at different distances from their breeding sites. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 81: 215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duerr HP, Eichner M, 2010. Epidemiology and control of onchocerciasis: the threshold biting rate of savannah onchocerciasis in Africa. Int J Parasitol 40: 641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Awadzi K, et al. 2004. An investigation of persistent microfilaridermias despite multiple treatments with ivermectin, in two onchocerciasis-endemic foci in Ghana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 98: 231–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Churcher TS, Pion SD, Osei-Atweneboana MY, Prichard RK, Awadzi K, Boussinesq M, Collins RC, Whitworth JA, Basanez MG, 2009. Identifying sub-optimal responses to ivermectin in the treatment of river blindness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 16716–16721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osei-Atweneboana MY, Awadzi K, Attah SK, Boakye DA, Gyapong JO, Prichard RK, 2011. Phenotypic evidence of emerging ivermectin resistance in Onchocerca volvulus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyle SR, et al. 2017. Genome-wide analysis of ivermectin response by Onchocerca volvulus reveals that genetic drift and soft selective sweeps contribute to loss of drug sensitivity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0005816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crosskey RW, 1981. A review of S. damnosum s. l. and human onchocerciasis in Nigeria, with special reference to geographical distribution and the development of a Nigerian national control campaign. Tropenmed Parasitol 32: 2–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loum D, Cozart D, Lakwo T, Habomugisha P, Jacob B, Cupp EW, Unnasch TR, 2019. Optimization and evaluation of the Esperanza Window trap to reduce biting rates of Simulium damnosum sensu lato in northern Uganda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13: e0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]