ABSTRACT

A delay in diagnosis and initiation of treatment in patients with tuberculosis (TB) can affect the period of communicability and cost of treatment. We aimed to describe the diagnostic pathways and delays in initiation of treatment among drug-sensitive newly diagnosed TB patients in Ballabgarh, India. In May 2019, we interviewed 110 TB patients who were put on treatment in the past 2 months. It was a cross-sectional study where data collection was conducted by a physician. We used a structured questionnaire to collect the information on care-seeking practices, delays, and patient’s cost. Descriptive analysis was carried out for the pathways, delays, and patient cost. The mean number of health facility contacted before the diagnosis of TB was 2.8 (SD: 1.3); 76% of patients first sought care at a private health facility. The median total delay was 34.5 (IQR: 21–60) days; median patient delay seven (IQR: 2–21) days, median health system delay 16 (IQR: 8–45) days, median diagnostic delay 32.5 (IQR: 18–57) days, and median treatment delay two (IQR: 1–3) days. Health system delay was 2.2 times longer than patient delay; the health system delay was primarily due to delay in diagnosis. Patients contacting private health facility first had 1.7 times total delay, 2.4 times longer health system delay, and 3.4 times of direct cost compared with patients contacting a public health facility first. Accelerated efforts are needed to achieve India’s target to eliminate TB by 2025.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a curable disease, and yet it is one among the top 10 causes of death in the world. According to the Global TB Report (2020), India had a high burden of TB, contributing to 26% of all new TB cases in the world.1 India has set a target to eliminate TB by 2025.2 One of the major challenges faced is the timely diagnosis as it primarily depends on patients reporting to the health facility. As a patient navigates through various health facilities, it leads to delay in diagnosis and treatment. Health system and patient factors, both contribute to the delay in the diagnosis and treatment of TB.3 Delay in the treatment of TB increases the period of infectivity of the patient as well as the morbidity and mortality due to the disease.4–6 Therefore, one of the key focuses of the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP) in India is early diagnosis and prompt treatment.2 Information on the diagnostic pathways is vital to plan an intervention to reduce the delay incurred in diagnosis or treatment. The literature for the diagnostic pathways in India is sparse and mostly limited to South India.7–9 To generate evidence from the northern region of the country, we conducted this study.

Studies in India have found that most of the TB patients seek care at the private health facilities first, which is also associated with increased patients’ costs and delay in the diagnosis and treatment.7,10,11 One study done in Tamil Nadu found that patients who visited private health facility first had higher odds of high pre-diagnosis direct cost and health system delay than the patients who presented first to the public health facility.7 Patients seeking care at the private health facility cannot avail the free diagnostic and treatment services provided under the national program, resulting in incurring of direct and indirect costs.12 We conducted this study to identify the diagnostic pathways, quantify delays in initiation of treatment among drug-sensitive newly diagnosed TB patients, and assess the determinants and consequences of the delay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting.

This was part of a longitudinal study to assess the costs for TB care conducted in the Ballabgarh block of Faridabad district in Haryana, India. We enrolled patients from the two of the nine TB units in the block, one each from the rural and urban areas based on feasibility and convenience.

Study population and sampling.

Sample size was estimated assuming 45% of patients to have a total delay of more than 30 days,13 with 10% of absolute precision, and considering 15% as nonresponse rate. The total sample size was calculated as 109. We included all consecutive newly diagnosed drug-sensitive adult TB patients who were initiated on daily observed treatment short course (DOTS) between March 1, 2019 and May 15, 2019. Information on TB patients was obtained from the TB register at the tuberculosis units (TUs). Patients whom we were unable to contact after two attempts were excluded.

Data collection.

Data were collected from May 1–15, 2019. Data were collected at the DOTS center or by visiting patients’ residence. We collected data using a semi-structured questionnaire for a sociodemographic profile; the first symptom patient presented with, the first health facility patient visited, date of diagnosis, date of treatment initiation, visits to health facilities, and the patients’ costs. The patients’ costs were captured using WHO’s tool to estimate patient’s costs.14 We also collected data on alcohol and tobacco use. Hazardous drinking for alcohol use was based on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-C score, score ≥ 4 for women and ≥ 5 for men was considered as hazardous drinking for alcohol.15 A current smoker was defined as a person who has smoked more than 100 cigarettes/bidi/hookah in his or her lifetime and has smoked in the last 30 days. All data were collected using Epicollect5 application16 in the tablet, except the data regarding the cost which was collected on paper and later entered into MS Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). The data regarding the date of diagnosis and treatment initiation and the patient cost were verified with the available bills and documents.

Operational definitions.

Heath facilities were classified into two categories, that is, public health facility and private health facility. A public health facility included tertiary or secondary government hospital, primary health center, and subcenter. Daily observed treatment short centers are public health facilities, where TB patients are given medications under the direct supervision and followed up. A private health facility included private hospitals or clinics, private practitioners, and traditional healers.7 We adopted the framework of time delay followed by the WHO.17 The total delay was defined as the time interval from the onset of symptoms till the date of antituberculosis treatment initiation. The total delay was further classified as the patient delay, health system delay, diagnostic delay, and treatment delay. The patient delay was the interval from the onset of symptoms till the first health facility contact. Health system delay was the interval from the first health facility contact till the date of initiation of TB treatment. Diagnostic delay was the interval from the onset of symptoms till the date of TB diagnosis. Treatment delay was the interval from the date of diagnosis to the date of initiation of its treatment. The diagnosis was made as per the NTEP guidelines. The direct cost included the cost of consultation, investigation, medication, hospitalization, paperwork, accommodation, travel, food during travel, and nutritional supplements.18 Indirect cost was calculated for patients and caregivers using the human capital approach with correction for equity, as it takes into account for the time lost by unemployed individuals.19

Data analysis.

Statistical data analysis was performed in STATA 13.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX). Descriptive analysis was carried out for pathways, delays, and patient cost. The cost is presented in USD for the year 2019 ($1 = INR 71) as mean (SD) and median (IQR). To assess the relationship between the cost (dependent variable) and delay (predictor variable), the cost was log-transformed before linear regression was calculated.20 For interpretation, the beta coefficient was exponentiated, one was subtracted, and followed by multiplication by 100 to get the percentage increase/decrease in the response for a one-unit change in the predictor variable.21 We used bivariable and multivariable logistic regression to assess the determinants of total delay > 30 days. Health system delay and the diagnostic delay were dichotomized by the median cutoff value to identify the determinants of health system delay and diagnostic delay. We did not determine the factors associated with patient delay and treatment delay as these delays were comparatively shorter than the other delays. All the factors which were potentially significant (P-value < 0.2) in the bivariable analysis were considered for the multivariable logistic regression model. Cost and delay were compared across the type of the first health facility contact using a test of significance (Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test), and P-value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Ethics.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institute Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi (IECPG- 520/November 14, 2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

RESULTS

Profile of patients.

A total of 165 patients were eligible in which 55 patients could not be contacted. Among the excluded patients (n = 55), the median age was 35 (IQR: 27–52) years; most of them were male (72.7%), resided in an urban area (89.1%), and had pulmonary TB (80%). A total of 110 TB patients were enrolled in this study. The median age of 110 patients in the study was 30 (IQR: 24–44) years; 38 (43.5%) were in the age-group of 18–25 years, 46 patients (41.8%) were in the age group of 26–45 years, and 26 patients (23.7%) were of the age-group of 46 years and above. The majority of them were male (54.5%), and most of the patients (73.6%) resided in an urban area. Pulmonary TB was diagnosed among 74 patients (67.3%). The most common reported the first symptom was cough (52.8%) (Supplemental Table 1).

Diagnostic pathways.

The mean number of health facilities contacted before reaching the DOTS center was 2.8 (SD: 1.3). Most of the patients (75.5%) sought care in a private health facility first. A total of 29 diagnostic pathways were found in which the most common (23.6%) pathway was the first visit to a private health facility followed by a visit to a public health facility before reaching the DOTS center (Supplemental File). A total of 44 patients (40%) were referred from the first contacted private health facility to a public health facility. Only five patients were directly referred to the DOTS center from a private health facility. Two patients visited the emergency department of a public health facility for their symptoms. The median number of investigations carried out was three (IQR: 2–4). The median number of the radiological and microbiological tests was one (IQR: 0–2) and one (0–1), respectively. In total, 56% of X-rays and 77.9% of sputum microscopic examinations were performed at public health facilities, and 52.6% of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and 88.2% of CT scan were carried out at private health facilities (detail in the Supplemental File).

Delays and its determinants.

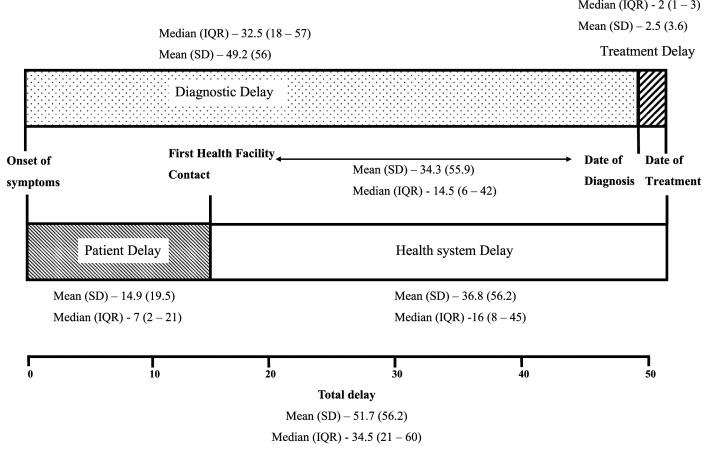

The median total delay was 34.5 (IQR: 21–60) days; median patient delay seven (IQR: 2–21) days, median health system delay 16 (IQR: 8–45) days, median diagnostic delay 32.5 (IQR: 18–57) days, and median treatment delay two (IQR: 1–3) days (Figure 1). The health system delay was longer than the patient delay. Primarily, the health system delay was related to the diagnosis as the median duration from the first health facility contact to the diagnosis was 14.5 (IQR: 6–42) days and mean duration was 34.3 (SD: 34.3) days. The proportion of patients with a patient delay of more than 2 weeks was 34.5% (n = 38). The majority of the patients provided reasons for a patient delay of more than 2 weeks as they thought it as mild symptoms (n = 22); 14 patients used over-the-counter drugs for the symptoms, and two patients were busy with work. The proportion of patients with a total delay of more than 30 days was 66 (60%). In the multivariable analysis, patients visiting a private health facility first had 2.8 times (95% CI: 1.1–7.1, P-value −0.028) higher odds of having total delay of more than 30 days than the patients who first visited a public health facility (Table 1). Patients visiting a private health facility first had 7.2 times (95% CI: 2.2–23.2, P-value −0.001) higher odds of having health system delay (above median 16 days) than the patients who first visited a public health facility (Supplemental File). Patients who first visited a private health facility had 1.7 times longer total delay (40 days versus 23 days) and 2.4 times longer health system delay (24 days versus 10 days) than patients who first visited a public health facility (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Delays (in days) in initiation of treatment among adult patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis at Ballabgarh, India.

Table 1.

Factors associated with a total delay of > 30 days among adult patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis at Ballabgarh, India

| Variable | Patients with total delay > 30 days (n = 66) | Bivariable analysis cOR (95% CI) | Multivariable analysis aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 18–30 (n = 59) | 36 (61%) | 1 | Not included |

| ≥ 31 (n = 51) | 30 (58.8%) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | ||

| Gender | Female (n = 50) | 35 (94.3%) | 1 | 1 |

| Male (n = 60) | 31 (51.7%) | 0.45 (0.2–1) | 0.7 (0.2–2) | |

| Years of education | 0–5 (n = 43) | 25 (58.1%) | 1 | Not included |

| ≥ 6 (n = 67) | 41 (61.2%) | 1.1 (0.5–2.5) | ||

| Wealth index (quintiles) | Lowest (0–20%) | 11 (50%) | 1 | Not included |

| Second (20–40%) | 15 (68.2%) | 2.1 (0.6–7.3) | ||

| Middle (40–60%) | 13 (59.1%) | 1.4 (0.4–4.7) | ||

| Fourth (60–80%) | 14 (63.6%) | 1.7 (0.5–5.8) | ||

| Highest (80–100%) | 13 (59.1%) | 1.4 (0.4–4.7) | ||

| Total annual family income (US $) | < 2,500 (n = 56) | 34 (60.7%) | 1 | Not included |

| > 2,500 (n = 54) | 32 (59.3%) | 0.9 (0.4–2) | ||

| Occupation | Employed (n = 58) | 32 (55.2%) | 1 | Not included |

| Not employed (n = 52) | 34 (65.4%) | 1.5 (0.7–3.3) | ||

| Residence | Urban (n = 81) | 51 (63%) | 1 | Not included |

| Rural (n = 29) | 15 (51.7%) | 0.63 (0.2–1.4) | ||

| First health facility contact | Private (n = 83) | 55 (66.3%) | 2.8 (1.1–6.9) | 2.8 (1.1–7.1) |

| Public (n = 27) | 11 (40.7%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Smoking | Never smoker (n = 70) | 46 (65.7%) | 1 | 1 |

| Ever smoker (n = 40) | 20 (50%) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.9) | |

| Smokeless tobacco use | Never user (n = 102) | 61 (59.8%) | 1 | Not included |

| Ever user (n = 8) | 5 (62.5%) | 1.1 (0.3–4.9) | ||

| Hazardous drinking | Absent (n = 99) | 60 (60.6%) | 1 | Not included |

| Present (n = 11) | 6 (54.5%) | 0.8 (0.2–2.7) | ||

| Type of TB | Pulmonary (n = 74) | 44 (59.5%) | 1 | Not included |

| Extrapulmonary (n = 36) | 22 (61.1%) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | ||

cOR = crude odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio.

Table 2.

Health system delay and the patients' costs by the type of first health facility contacted among adult patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis at Ballabgarh, India

| Variable | First health facility contact | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private (n = 83) | Public (n = 27) | ||

| Median total delay,* days (IQR) | 40 (25–63) | 23 (15–42) | 0.007 |

| Median health system delay,† days (IQR) | 24 (10–48) | 10 (7–14) | 0.000 |

| Median direct pre-diagnosis cost, $ (IQR) | 38.5 (19.5–84.2) | 11.3 (4.5–28.6) | 0.000 |

| Median indirect pre-diagnosis cost, $ (IQR) | 38.5 (16.8–140.3) | 70.1 (16.6–192.4) | 0.295 |

| Median total pre-diagnosis cost, $ (IQR) | 115.9 (46.3–204.3) | 92.0 (48.6–194.8) | 0.864 |

Bold values indicate significant P-value < 0.05.

Total delay is the time interval from the onset of symptoms till the date of antitubercular treatment initiation.

Health system delay is the time interval from the health facility contact till the date of initiation of TB treatment.

Association between delay and costs.

The median total pre-diagnosis cost was $92.6 (46.8–194.8). The median direct and indirect costs were $31.7 (IQR: 12.9–63.8) and $43.6 (IQR: 16.8–150.8), respectively. Patients who first visited a private health facility had 3.4 times higher direct cost ($38.5 versus $11.3) than patients who first visited a public health facility. One day increase in health system delay increased the direct cost by 0.7% (95% CI: 0.2–1.1, P-value 0.005) and 1 day increase in the total delay increased the direct cost by 0.5% (95% CI: 0.1–1, P-value 0.041). Total delay and health system delay increased cost in the form of the direct mical cost.

DISCUSSION

We found that most of the TB patients (75.5%) sought care initially in a private health facility, and they had longer total delay (1.7 times), health system delay (2.4 times), and direct cost (3.4 times) than the patients who initially visited public health facility. An increase in delay increased the patients’ direct costs. The mean total delay, patient delay, and treatment delay were similar to the findings of a systematic review conducted among pulmonary TB patients in India.22 The median patient delay in our study was less than the results of studies conducted in Himachal Pradesh11 and Puducherry23 in India. This difference could be due to the specific factors which affect the patient delay, for example, accessibility to health facilities, residence setting, income, gender, knowledge of TB, and risky alcohol use among the patients.11,23–26 The health system delay was primarily due to delay in the diagnosis as patients had to visit a higher health facility for the diagnostic facilities, which was similar to the findings of Purohit et al.9 The median number of health facilities visited before the diagnosis was similar to findings of Sreeramareddy et al.22 We found a higher proportion of patients who first visited a private health facility, which was similar to the studies conducted in other parts of India (Tamil Nadu,7 Delhi,25 and Karnataka10). This could be because of easy access or the convenience of visiting a private health facility. The decision of selecting the first healthcare facility depends on the trust in the provider, easy access or convenience, cost, and perceived cause of the disease.10,25,27

We found that the patients who first visited a private health facility had longer health system delay, higher patients’ costs, and 2.8 times higher odds of total delay of more than 30 days compared with the patients who first visited a public health facility. These findings were similar to other studies conducted in India.7,11 Such findings could be due to inadequate diagnosis, suboptimal quality of care, and irrational treatment protocol at the private health facilities.28–31 We found that with the increase in total delay and health system delay, there was an increase in the direct cost as well. This finding was quite similar to a study conducted in Yemen which reported high patients’ costs among the TB patients with delay in diagnosis (delayed group).32 One study in Tamil Nadu found that the patients who first visited a private facility were 17 times more likely to have high direct pre-diagnosis cost (more than the median $7.7) and 1.8 times more likely to have health system delay (more than the median 21 days) than the patients who first visited a public health facility.7

Even after providing free diagnosis and treatment services in the public health facilities by the NTEP in India,2 most of the patients seek care at a private health facility, which is associated with a longer health system delay and total delay. The government of India took initiatives such as the involvement of private health facilities and mandatory notification of TB; despite this, there is a substantial total delay. As the delay is primarily related to the diagnosis of the disease and not due to delay in presentation to health facility or notification, reorientation of doctors and emphasis on implementation of TB guidelines for diagnosis and treatment can reduce the delays, especially in private health facilities. Increasing the accessibility and convenience to the public health facilities, and provision of diagnostics for extrapulmonary TB under the NTEP needs to be focused. Delay in the diagnosis of TB remains a significant challenge to achieve India’s target to eliminate TB by 2025. Accelerated efforts need to be made for early diagnosis and prompt treatment of TB. The strategy of active case finding for TB has demonstrated promising results to reduce the delays and patients’ cost in India.33–35 Active screening of TB in the emergency department among patients seeking care for respiratory symptoms can also be considered to achieve the target for TB elimination.36 We used a standardized tool to capture the patients’ costs and delay. Patients started on treatment in March were enrolled in May; this gap of 2 months could have resulted in recall bias. This study was not powered to assess factors associated with various delays. The results of this study cannot be generalized to suspected cases of TB as this study was limited to confirmed cases of TB. We excluded the patients (n = 55) who could not be contacted after two attempts. It is unlikely to cause any selection bias as in the subgroup analysis; we did not find any difference in the total delay across the age, gender, type of TB, and residence.

CONCLUSION

Most of the TB patients initially sought care in a private health facility. The most common diagnostic pathways before reaching the DOTS center was visiting a private health facility, followed by a visit to a public health facility. Health system delay was 2.2 times longer than patient delay, and it was primarily because of the delay in diagnosis. An increase in the health system delay and total delay increased the patient’s pre-diagnosis costs. Patients who initially visited a private health facility were found to have longer health system delay, high direct cost, and more likely to have a total delay of more than 30 days as compared with patients who initially visited public health facility.

Supplemental file and tables

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

Note: Supplemental file and tables appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization , 2020. Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed August 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Central Tuberculosis Division, India , 2020. National strategic plan for tuberculosis elimination 2017–2025. Available at: https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/NSP%20Draft%2020.02.2017%201.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paramasivam S, Thomas B, Chandran P, Thayyil J, George B, Sivakumar CP, 2017. Diagnostic delay and associated factors among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Kerala. J Family Med Prim Care 6: 643–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toman K, 2004. Toman’s Tuberculosis: Case Detection, Treatment, and Monitoring: Questions and Answers, 1st edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Styblo K, Enarson DA, 1991. Epidemiology of tuberculosis, Vol. 24. The Hague, Netherlands: The Hague Royal Netherlands Tuberculosis Association. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yb28ub4h. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldhubhani AH, Izham MM, Pazilah I, Anaam MS, 2013. Effect of delay in diagnosis on the rate of tuberculosis among close contacts of tuberculosis patients. East Mediterr Health J 19: 837–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veesa KS, et al. 2018. Diagnostic pathways and direct medical costs incurred by new adult pulmonary tuberculosis patients prior to anti-tuberculosis treatment–Tamil Nadu, India. PLoS One.13: e0191591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yellappa V, Lefèvre P, Battaglioli T, Devadasan N, Van der Stuyft P, 2017. Patients pathways to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in a fragmented health system: a qualitative study from a south Indian district. BMC Public Health 17: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purohit MR, Purohit R, Mustafa T, 2019. Patient health seeking and diagnostic delay in extrapulmonary tuberculosis: A hospital based study from central India. Tuber Res Treat 2019: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumana M, Sreelatha CY, Renuka M, Ishwaraprasad GD, 2016. Patient and health system delays in diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis patients in an urban tuberculosis unit of south India. Int J Commun Med Public Health 3: 796–804. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakur R, Murhekar M, 2013. Delay in diagnosis and treatment among TB patients registered under RNTCP Mandi, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2010. Indian J Tuberc 60: 37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarin R, Vohra V, Singla N, Thomas B, Krishnan R, Muniyandi M, 2019. Identifying costs contributing to catastrophic expenditure among TB patients registered under RNTCP in Delhi metro city in India. Indian J Tuberc 66: 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronner Murrison L, Ananthakrishnan R, Swaminathan A, Auguesteen S, Krishnan N, Pai M, Dowdy DW, 2016. How do patients access the private sector in Chennai, India? An evaluation of delays in tuberculosis diagnosis. Int J Tuber Lung Dis 20: 544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.KNCV Tuberculosis Foundation, World Health Organization JA-TA , 2008. Tool to Estimate Patients’ Costs. Available at: http://www.stoptb.org/wg/dots_expansion/tbandpoverty/assets/documents/Tool%20to%20estimate%20Patients'%20Costs.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khadjesari Z, White IR, McCambridge J, Marston L, Wallace P, Godfrey C, Murray E, 2017. Validation of the AUDIT-C in adults seeking help with their drinking online. Addict Sci Clin Pract 12: 2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imperial College London , 2018. Epicollect 5. Available at: https://five.epicollect.net/. Accessed August 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization , 2006. Diagnostic and Treatment Delay in Tuberculosis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: http://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa710.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization , 2017. Tuberculosis Patient Cost Surveys: A Handbook. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedrazzoli D, Borghi J, Viney K, Houben R, Lönnroth K, 2019. Measuring the economic burden for TB patients in the end TB strategy and universal health coverage frameworks. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 23: 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Wong W, Lamoureux EL, Wong TY, 2012. Are linear regression techniques appropriate for analysis when the dependent (outcome) variable is not normally distributed? Invest Ophthal Visual Sci 53: 3082–3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford C, 2018. Interpreting Log Transformations in a Linear Model. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Library. Available at: https://data.library.virginia.edu/interpreting-log-transformations-in-a-linear-model/. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sreeramareddy CT, Qin ZZ, Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Pai M, 2014. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 18: 255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Ness SE, et al. 2017. Predictors of delayed care seeking for tuberculosis in southern India: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis 17: 567–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bawankule S, Quazi SZ, Gaidhane A, Khatib N, 2010. Delay in DOTS for new pulmonary tuberculosis patient from rural area of Wardha District, India. Online J Health Allied Sci 9: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhaked S, Sharma N, Chopra KK, Khanna A, Kumar R, 2018. Treatment seeking pathways in pediatric tuberculosis patients attending DOTS centers in urban areas of Delhi. Indian J Tuberc 65: 308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai J, Wang X, Ma A, Wang Q, Han X, Li Y, 2015. Factors associated with patient and provider delays for tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10: e0120088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maske AP, Sawant PA, Joseph S, Mahajan US, Kudale AM, 2015. Socio-cultural features and help-seeking preferences for leprosy and tuberculosis: a cultural epidemiological study in a tribal district of Maharashtra, India. Infect Dis Poverty 4: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satyanarayana S, et al. 2015. Quality of tuberculosis care in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 19: 751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarosławski S, Pai M, 2012. Why are inaccurate tuberculosis serological tests widely used in the Indian private healthcare sector? A root-cause analysis. J Epidemiol Global Health 2: 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelkar-Khambete A, Kielmann K, Pawar S, Porter J, Inamdar V, Datye A, Rangan S, 2008. India’s revised national tuberculosis control programme: looking beyond detection and cure. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 12: 87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Udwadia ZF, Pinto LM, Uplekar MW, 2010. Tuberculosis management by private practitioners in Mumbai, India: has anything changed in two decades? PLoS One 5: e12023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aldhubhani AHN, Ibrahim MIM, Ibrahim P, Anaam MS, Alshakka M, 2017. Effect of delay in tuberculosis diagnosis on pre-diagnosis cost. J Pharm Pract Commun Med 3: 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shewade HD, et al. 2018. Active case finding among marginalised and vulnerable populations reduces catastrophic costs due to tuberculosis diagnosis. Glob Health Action 11: 1494897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muniyandi M, et al. 2020. Catastrophic costs due to tuberculosis in south India: comparison between active and passive case finding. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 114: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mani M, Riyaz M, Shaheena M, Vaithiyalingam S, Anand V, Selvaraj K, Purty AJ, 2019. Is it feasible to carry out active case finding for tuberculosis in community-based settings? Lung India 36: 28–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva DR, Müller AM, da Silva Tomasini K, Dalcin PTR, Golub JE, Conde MB, 2014. Active case finding of tuberculosis (TB) in an emergency room in a region with high prevalence of TB in Brazil. PLoS One 9: e107576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.