ABSTRACT

Thousands of Palestinian and Arab–Israeli pilgrims travel to Mecca each year to complete their pilgrimage. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have characterized the infectious and noninfectious morbidity among Arab–Israeli or Palestinian Hajj pilgrims. Thus, we designed and conducted an observational questionnaire-based study to prospectively investigate the occurrence of health problems among these Hajjis who traveled to complete their Pilgrimage during 2019 Hajj season. For the purpose of the study, questionnaires were distributed to Hajj pilgrims at three different time occasions—before travel, inquiring on demographics and medical comorbidities; and 1 and 4 weeks after returning recording any health problems encountered during or after travel. Initial recruitment included 111 Hajjis. The mean age of responders was 49.5 (±9.1) years, with a Male:Female ratio of 1.3:1. The mean travel duration was 18.7 (13–36) days. Altogether, 66.3% of the pilgrims reported at least one health problem during and after the trip, of which 38.6% sought medical attention. Five (4.8%) hajjis were hospitalized, including life-threatening conditions. Cough was the most common complaint (53.8%), and 11.5% also reported fever. Pretravel counseling was associated with reduced outpatient and emergency room visits. We therefore concluded that a high rate of morbidity was reported among this cohort of Hajj pilgrims with a morbidity spectrum similar to pilgrims from other countries. Pretravel consultation with the purpose of educating the pilgrims on the health risks of Hajj may help reduce the morbidity for future Hajj seasons.

INTRODUCTION

The WHO defines mass gatherings as “events attended by a sufficient number of people to strain the planning and response resources of a community, state, or nation.”1,2 A major public health concern in relation to mass gatherings is spread of infectious diseases between attendees, to the local population, and back to travelers’ countries of origin. Examples of such mass gathering events include the Olympic games and the Kumbha Mela religious festival in India.

As the largest annual mass gathering in the world, the hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca is of central importance to the Muslim nation being the fifth pillar of Islam and a duty for all able-bodied financially capable Muslims.3 Almost 10,000 Palestinian and Arab–Israeli pilgrims make their way to Mecca each year to complete their pilgrimage.4 For the purpose of obtaining a Hajj visa, all hajjis including Palestinian and Arab–Israelis are required to submit a proof of valid quadrivalent (ACYW) meningococcal vaccine within the last 3–5 years, administered not less than 10 days before the planned arrival in Saudi Arabia.5 Influenza vaccine is also recommended but not obligatory for traveling pilgrims.6 Palestinian pilgrims are usually vaccinated at primary healthcare clinics, whereas Arab–Israeli pilgrims are usually vaccinated at travel clinics or primary healthcare clinics.4 Participation of both Palestinian and Arab–Israeli pilgrims is limited by the Hajj quota, set at 7,000 for Palestinian pilgrims and 3,500 for Arab–Israelis. A decision to grant an exit permit for the round-trip journey to Mecca is given based on a priority list, with older applicants receiving higher priority. This has resulted in thousands of Hajjis being denied exit permits, with some of them having to wait several decades to fulfill their pilgrimage. These complex requirements coupled with the significant financial burden lead to an elderly population of travelers who may be vulnerable to communicable diseases, injuries, and exacerbation of known chronic illnesses.

In this article, we prospectively investigated the occurrence of common health problems among Arab–Israeli and Palestinian Hajjis who traveled to complete their Pilgrimage during the 2019 Hajj seasons using a questionnaire administered before and after Hajj travel.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and population.

We designed and conducted a prospective observational questionnaire-based study. The study population included pilgrims aged 18 years or older who agreed to participate and from whom informed consent was obtained. The pilgrims were both Arab–Israeli and Palestinians residing mainly in Jerusalem and in the Central District of Israel who intended to travel to complete their Pilgrimage during 2019 Hajj season. Recruitment of participants was performed on a voluntary basis by pilgrims who attended the pre-Hajj educational meetings and conferences. These meetings are held annually by religious committees of local Israeli and Palestinian towns.

Questionnaires were distributed to Hajj pilgrims on three different time occasions—within 1 month before Hajj travel and then 1 and 4 weeks after returning. The pretravel questionnaire evaluated different aspects such as demographic characteristics (age, gender, country of birth, location of residence, profession, and level of education), pretravel morbidity (chronic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and malignancies), means of transportation to Mecca, duration of stay, and living condition during their stay. In the post-return questionnaire, all morbidities (infectious and noninfectious) were recorded, including outpatient visits and hospitalization during their stay and during the 4-week period after their return to Israel. The study was approved by the Sheba Medical Center local Ethics Committee (approval code 5982-19-SMC).

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were computed as mean ± SD, whereas categorical variables were recorded as percentages where appropriate. Such variables were compared between two groups. Alpha was set at the P-value critical cutoff of 0.05, and comparison between categorical groups was carried out with the use of the Pearson chi-square test, and comparison of means between groups was analyzed by independent t‐test. The Mann–Whitney test was used for nonparametric analysis.

RESULTS

One hundred eleven pilgrims were recruited in the initial questionnaire, whereas 104 hajjis completed the post-travel questionnaire, thus yielding a completion rate of 93.6%. The demographic characteristics of enrolled hajjis and the characteristics of their Hajj journey are presented in Table 1 in the following text. Altogether, respondents had a mean age of 49.5 (±9.1) years, with a gender ratio M/F of 1.3. The mean duration of travel was 18.7 days (13–36 days).

Table 1.

Demographic and travel characteristics of traveling Hajj pilgrims

| Demographic characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 49 (29–69) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Males | 64 (57.7) |

| Nationality, no. (%) | |

| Arab–Israeli | 31 (27.9) |

| Palestinians | 80 (72.1) |

| Travel characteristics | |

| Mean travel duration (days) (range) | 18.7 (13–36) |

| Method of travel, no. (%) | |

| Airplane | 79 (71.2) |

| Bus | 26 (23.4) |

| Special travel vehicles | 6 (5.4) |

| Receipt of pretravel counseling, no. (%) | |

| Yes | 69 (62.2) |

| No | 42 (37.8) |

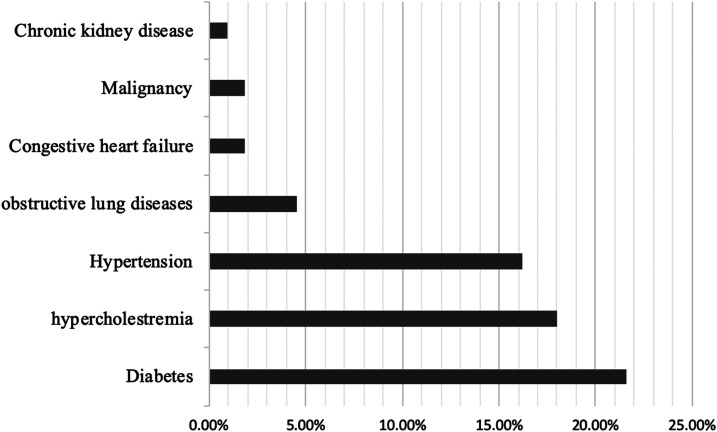

Figure 1 illustrates the baseline chronic illnesses that were reported among the hajjis. Forty-three (38.7%) enrolled participants reported having a chronic illness before their travel. The most common chronic illness reported among the traveling pilgrims was diabetes (21.6%). Twenty-three of the participants (20.6%) were smokers. Thirty (28.0%) pilgrims received the seasonal influenza vaccine.

Figure 1.

Baseline chronic diseases among traveling pilgrims.

Among the 104 hajjis (93%) who completed the post-travel questionnaire, 50 (45.0%) were on regular medications, and the majority of them (74.5%) did adhere to taking their medications regularly. Ninety-seven pilgrims (93.3%) avoided drinking tap water, and 100 pilgrims (96.2%) reported eating hotel-prepared meals only. The vast majority of male hajjis (83%) used disposable single-use razor blades for the ritual shaving.

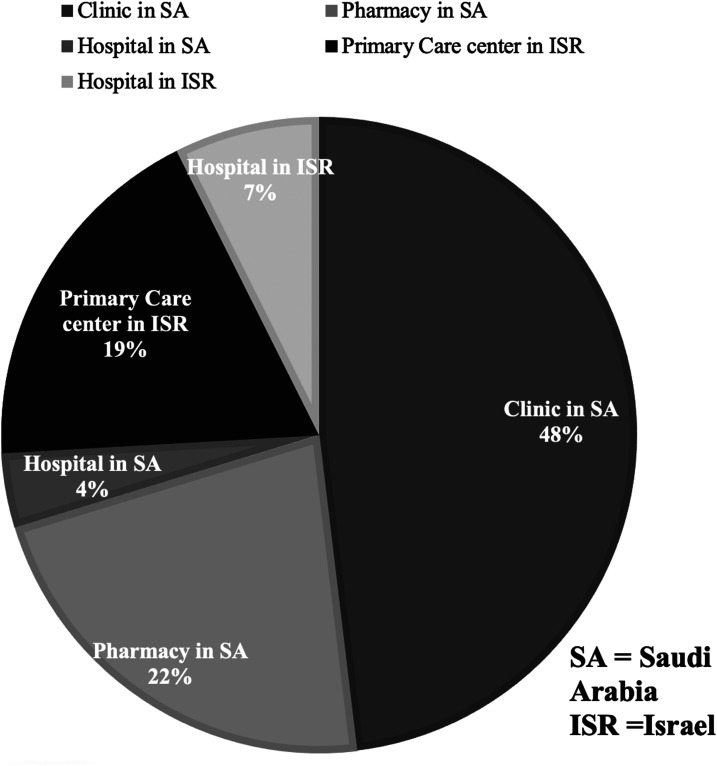

A total of 69 (66.3%) pilgrims reported at least one health problem, of which 27 (38.6%) sought medical attention in Saudi Arabia (74.0%) and Israel (26.0%) (Figure 2). Of those who sought medical attention, 11% reported cough and fever.

Figure 2.

Location of treatment of sick Hajj pilgrims, expressed in percentages.

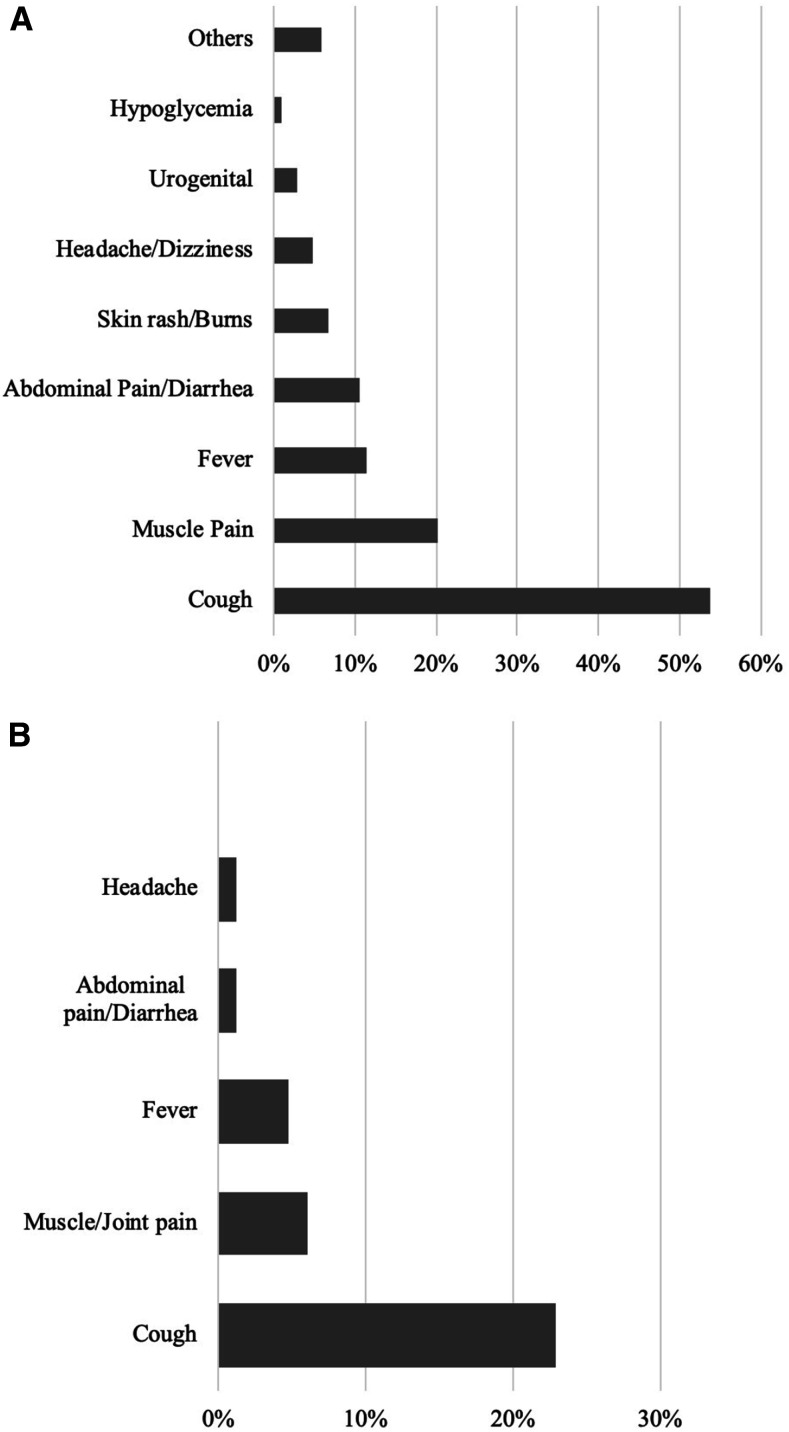

As shown in Figure 3A, the most commonly reported health problem among the traveling hajjis was cough, reported by 56 hajjis (53.8%). Of those, 12 pilgrims (11.5%) reported having both fever and cough. A total of five hajjis (4.8%) were hospitalized (one in Saudi Arabia and four in Israel on returning), of which three (2.9%) reported having life-threatening conditions: central venous–associated infection in a dialysis patient, acute appendicitis, and febrile neutropenia. All the admitted pilgrims were eventually discharged, and no deaths were reported among the cohort.

Figure 3.

Reported health problems at 1 and 4 weeks post-travel.

Figure 3B shows the health problems recorded at the subsequent questionnaire at week 4, which resembles the trend that was observed in the week 1 questionnaire, with a significant resolution of most of the complaints apart from cough that persisted in almost 23% of pilgrims 4 weeks after returning from the pilgrimage (Figure 2B).

With regard to symptoms reported among the traveling pilgrims, no statistically significant differences were observed between different age or gender groups (Table 2). In addition, the baseline health status, smoking status, vaccination status, and the means of travel had no statistically significant influence on the symptoms reported by traveling hajjis.

Table 2.

Health problems and seeking medical care with regard to different variables

| Seek medical care, n (%) | P-value | Any health problems, n (%) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 11 (33.3) | 22 (66.7) | 0.70* | 34 (60.7) | 22 (39.3) | 0.59* |

| Female | 11 (37.9) | 18 (62.1) | 29 (65.9) | 15 (34.1) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 50 | 13 (32.5) | 27 (67.5) | 0.50* | 41 (68.3) | 19 (31.7) | 0.17* |

| ≥ 50 | 9 (40.9) | 13 (59.1) | 22 (55) | 18 (45) | ||

| Health status | ||||||

| Previously healthy | 15 (38.5) | 24 (61.5) | 0.52* | 39 (61.9) | 24 (38.1) | 0.76* |

| Chronic illness† | 7 (30.4) | 16 (69.6) | 24 (64.9) | 13 (35.1) | ||

| Prior counselling‡ | ||||||

| Yes | 11 (25.6) | 32 (74.4) | 0.014* | 44 (69.8) | 19 (30.2) | 0.06* |

| No | 11 (57.9) | 8 (64.5) | 19 (51.4) | 18 (48.6) | ||

| Prior vaccination | ||||||

| Yes | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 0.60* | 15 (55.6) | 12 (44.4) | 0.45* |

| No | 14 (32.6) | 29 (67.4) | 44 (63.8) | 25 (36.2) | ||

Bold indicates pilgrims who had prior counseling sought medical attention less than their counterparts who had no prior counseling (25.6% vs. 74.4, P = 0.014).

Chi-square test.

Chronic illness = chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and malignancies.

Prior counseling—prior medical debriefing about the potential health hazards that may complicate the health pilgrimage.

Finally, pilgrims who received a medical counseling before their travel sought medical attention less (25.6%) than those who did not (57.9%), and this was statistically significant (P = 0.014). No differences were observed with regard to seeking medical attention based on gender, age-groups, or health status.

DISCUSSION

A high rate of morbidity was reported among Arab–Israeli and Palestinian Hajj pilgrims, with 66.3% reporting at least one health problem. Our population was characterized by a high prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension—a feature that was observed in numerous previous studies. Similarly, the spectrum of morbidity observed among our cohort bears a strong resemblance to the morbidity seen in other hajj cohorts traveling from other countries.3,7 This is an important finding with several important health implications. First, this may help generalize the recommendations adapted worldwide to all traveling pilgrims, regardless of the countries they are traveling from. Second, it emphasizes the importance of environmental factors such as overcrowding, continuous close contact, and humid weather conditions as the key contributors to morbidity during the hajj season.

Cough was the most common health problem reported in our cohort (53.8% of the traveling hajjis). Interestingly, Gautret et al.7,8 reported a cough attack rate of 51.0% among French pilgrims in 2007, which was consistent with the results of their antecedent survey from 2006. Cough was even more common among Malaysian pilgrims, reported in 91.5% of them in a study conducted during the same Hajj season, with the variation in incidence attributed mainly to the severe climatic change for Malaysian Hajj pilgrims.9 Such variation in the incidence of cough among different cohorts may reflect differences in study design, study population, rates of vaccination, and the seasonal variation of upper respiratory tract infections, but “Hajj cough” remains one of the most common complaints reported by traveling pilgrims, regardless of their country of origin.

A significant proportion of the traveling pilgrims reported cough again at 4 weeks post-travel. The persistence of “Hajj cough” is a particularly interesting phenomenon that may be due to several possible etiologies. As upper respiratory tract infections tend to resolve in a relatively short time frame, possibilities to consider may include nonviral agents such as pertussis that has been established as a cause of prolonged cough among hajjis, with high acquisition rates of pertussis reported among pilgrims with no immunity to pertussis before travel or those with prolonged stay at Mecca.10 Other possible etiologies are atypical pulmonary infections such as mycoplasma and even tuberculosis, which has previously been reported in an Arab–Israeli pilgrim returning from Hajj.11 Because of the different causative agents that are thought to be involved and because vaccination alone is not sufficient to prevent respiratory illness in traveling pilgrims, behavioral measures such as hand hygiene, wearing a face mask, and cough etiquette represent the most realistic measures to prevent acute respiratory illnesses during the pilgrimage.

We did not observe any cases of major trauma in our cohort, despite being one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality during the Hajj.3 One plausible explanation to muscle pain being a common symptom among the traveling hajjis is the long distance traveled by pilgrims during the Hajj rituals such as Tawaf (the circumambulation seven times around the Kaa’ba), Sa’ay (walking seven times between the hills of Safa and Marwa), and the stoning of the pillars.

Diarrheal illnesses were encountered in about 11% of our cohort, much higher than the incidence encountered in the large Iranian studies (2.7% in 2004 and 2.8% in 2005) and by Gautret et al.7 in French pilgrims (4.5%).12 The majority of our hajjis (93.3%) avoided drinking tap water, and 96.2% reported eating hotel-prepared meals only. Almost all cases of gastroenteritis were self-limited and none were hospitalized, and no cases of dysentery were reported in our cohort. Despite being a significant threat in the past, notably due to cholera outbreaks, recent data indicate a shift toward lower prevalence that may be largely attributed to the improved sanitary conditions in Saudi Arabia, the better health education among the traveling pilgrims with a heightened sense of hygiene.13 During the hajj, handwashing is regularly carried out by pilgrims under at ritual purification, often called ablution (Wudu) that is performed in most cases before the five daily obligatory prayers. Consequently, hand hygiene compliance is high among pilgrims during Hajj.14 A recent study conducted on French pilgrims in 2016 found a lower prevalence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pilgrims who declared washing their hands more frequently at the Hajj than usually as than others.15

Twenty-two percent of our study cohort had diabetes mellitus. A single episode of hypoglycemia was reported, and no cases of diabetic ketoacidosis or non-ketotic hyperosmolar state were identified. This is similar to the results found by Gautret et al.7 where 2.6% of the individuals suffering from diabetes had cases of unstable diabetes (defined as extremes of blood sugar levels). Muslims with diabetes planning to make Hajj should make a pre-Hajj travel clinic visit to carefully construct a diabetes management plan tailored to the unique health challenges of the Hajj.

Acute cardiovascular system disorders were not observed among our cohort, despite a high proportion of pretravel cardiovascular morbidity in our cohort, and despite being reported as the most common cause of death during Hajj by the Saudi Ministry of Health.16

We evidenced a particularly high referral to outpatient clinics and emergency room visits in those who did not receive a pretravel medical counseling. This highlights the importance of educating the pilgrims on the potential health risks of Hajj pilgrimage before traveling, and providing them with simple yet effective strategies to tackle the most common health issues encountered during the pilgrimage. One way to ensure this comes to fruition is to assign all the traveling pilgrims to specialized Hajj pretravel clinics through direct cooperation with the authorized travel agencies. This may help ensure the complete vaccination of all traveling pilgrims and their education on health issues commonly encountered during hajj.

Eleven percent of our pilgrims had febrile respiratory illnesses after traveling to Saudi Arabia, which is consistent with the CDC definition of a probable case of Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-COV).17 Although most of the cases diagnosed were reported from Saudi Arabia, no laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV were found among the returning hajis who suffered acute respiratory illnesses on returning to their countries, despite vigorous surveillance.18–20

The lack of testing among our returning pilgrims with febrile respiratory illnesses is particularly worrisome not only in the context of probable MERS-CoV missed cases but also in light of the recent emergence and spread of the new novel coronary virus, officially known as COVID-19, to the Middle East region. Officially declared by the WHO as a pandemic on the March 11, 2020, the potential spread of the new novel coronary viruses during mass gathering events such as Hajj may lead to a massive spread of this infection with devastating consequences. Indeed, in the face of the escalating threat of COVID-19, Saudi Arabia had no choice but to impose several restrictions on 2020 Hajj attendees, limiting their number to about 10,000 Hajjis who reside within the country, as opposed to two million usually.

Our study has several limitations, with the main ones being the small number of participants and not having a “during Hajj” phase of the survey. Some degree of recall bias or self-reporting bias may have been present among the participants during the completion of post-travel questionnaires, but we tried to nullify that by interviewing our respondents at two different time frames after returning. In addition, we did not investigate the specific pathogens causing respiratory tract or gastrointestinal infections, but this was largely due to the lack of funding as meticulous microbiological testing has significant costs. The relatively young mean age of our population with significant baseline morbidity may have impacted the ability to detect any statistically significant differences among different age-groups, yet we think this is an accurately representative sample of people traveling from our region. Finally, the study was based on a limited number of subjects clustered mainly in east Jerusalem as pilgrims traveling from the west bank were difficult to reach having received their pretravel vaccinations at different primary health clinics scattered in different Palestinian cities. Therefore, our results cannot be extrapolated to the whole population of pilgrims participating in the Hajj. Nevertheless, this is the first study to prospectively characterize the infectious and noninfectious morbidity in Palestinian and Arab–Israeli pilgrims traveling from our region, and provides valuable information for future seasons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Hasan Ali for his active contribution in recruitment of pilgrims.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA, 2012. Mass gatherings and infectious diseases: prevention, detection, and control. Infect Dis Clin North Am 26: 725–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memish ZA, Al-Rabeeah AA, 2013. Public health management of mass gatherings: the Saudi Arabian experience with MERS-CoV. Bull World Health Organ 91: 899–899A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed QA, Arabi YM, Memish ZA, 2006. Health risks at the Hajj. Lancet 367: 1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilgrims HVftP , Available at: http://palestinecabinet.gov.ps/GovService/ViewService?ID=441.

- 5.Saudi Ministry of Health , 2019. Health Requirements and Recommendationsfor Travelers to Saudi Arabia for Hajj and Umrah 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA, 2019. The Hajj 2019 vaccine requirements and possible new challenges. J Epidemiol Glob Health 9: 147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautret P, Soula G, Delmont J, Parola P, Brouqui P, 2009. Common health hazards in French pilgrims during the Hajj of 2007: a prospective cohort study. J Trav Med 16: 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gautret P, Yong W, Soula G, Gaudart J, Delmont J, Dia A, Parola P, Brouqui P, 2009. Incidence of Hajj-associated febrile cough episodes among French pilgrims: a prospective cohort study on the influence of statin use and risk factors. Clin Microbiol Infect 15: 335–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deris ZZ, Hasan H, Sulaiman SA, Wahab MSA, Naing NN, Othman NH, 2010. The prevalence of acute respiratory symptoms and role of protective measures among Malaysian hajj pilgrims. J Travel Med 17: 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilder-Smith A, Earnest A, Ravindran S, Paton NI, 2003. High incidence of pertussis among Hajj pilgrims. Clin Infect Dis 37: 1270–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avnon LS, Jotkowitz A, Smoliakov A, Flusser D, Heimer D, 2006. Can the routine use of fluoroquinolones for community-acquired pneumonia delay the diagnosis of tuberculosis? A salutary case of diagnostic delay in a pilgrim returning from Mecca. Eur J Intern Med 17: 444–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meysamie A, Ardakani HZ, Razavi SM, Doroodi T, 2006. Comparison of mortality and morbidity rates among Iranian pilgrims in Hajj 2004 and 2005. Saudi Med J 27: 1049–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Sridhar S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA, 2015. Diarrhea at the Hajj and Umrah. Trav Med Infect Dis 13: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benkouiten S, Brouqui P, Gautret P, 2014. Non-pharmaceutical interventions for the prevention of respiratory tract infections during Hajj pilgrimage. Trav Med Infect Dis 12: 429–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sow D, et al. 2018. Acquisition of enteric pathogens by pilgrims during the 2016 Hajj pilgrimage: a prospective cohort study. Trav Med Infect Dis 25: 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saudi Ministry of Health , 2005. Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prevention CFDCA , 2015. Middle East respiratory syndrome: interim guidance for healthcare professionals. Centers Dis Control Prev. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma X, et al. 2017. No MERS-CoV but positive influenza viruses in returning Hajj pilgrims, China, 2013–2015. BMC Infect Dis 17: 715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amin M, Bakhtiar A, Subarjo M, Aksono EB, Widiyanti P, Shimizu K, Mori Y, 2018. Screening for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus among febrile Indonesian Hajj pilgrims: a study on 28,197 returning pilgrims. J Infect Prev 19: 236–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koul PA, Mir H, Saha S, Chadha MS, Potdar V, Widdowson MA, Lal RB, Krishnan A, 2018. Respiratory viruses in returning Hajj and Umrah pilgrims with acute respiratory illness in 2014–2015. Indian J Med Res 148: 329–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]