Abstract

The human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans relies on a complex signaling network for the adaptation and survival at the host temperature. Protein phosphatase calcineurin is central to proliferation at 37°C but its exact contributions remain ill-defined. To better define genetic contributions to the C. neoformans temperature tolerance, 4031 gene knockouts were screened for genes essential at 37°C and under conditions that keep calcineurin inactive. Identified 83 candidate strains, potentially sensitive to 37°C, were subsequently subject to technologically simple yet robust assay, in which cells are exposed to a temperature gradient. This has resulted in identification of 46 genes contributing to the maximum temperature at which C. neoformans can proliferate (Tmax). The 46 mutants, characterized by a range of Tmax on drug-free media, were further assessed for Tmax under conditions that inhibit calcineurin, which led to identification of several previously uncharacterized knockouts exhibiting synthetic interaction with the inhibition of calcineurin. A mutant that lacked septin Cdc11 was among those with the lowest Tmax and failed to proliferate in the absence of calcineurin activity. To further define connections with calcineurin and the role for septins in high temperature growth, the 46 mutants were tested for cell morphology at 37°C and growth in the presence of agents disrupting cell wall and cell membrane. Mutants sensitive to calcineurin inhibition were tested for synthetic lethal interaction with deletion of the septin-encoding CDC12 and the localization of the septin Cdc3-mCherry. The analysis described here pointed to previously uncharacterized genes that were missed in standard growth assays indicating that the temperature gradient assay is a valuable complementary tool for elucidating the genetic basis of temperature range at which microorganisms proliferate.

Keywords: temperature stress, fungal pathogenesis, septins, calcineurin, yeast

Introduction

Microbial cells are capable of proliferating within a specific temperature range, which is a characteristic of a given species or strain’s genetic background. For each species/strain, a minimum, a maximum, and an optimal temperature for growth can be defined (Rose and Evison 1965; Van Uden 1985). Our understanding of the genetic contribution to this specific temperature span remains incomplete. Microbial cells lack mechanisms to adjust and maintain their cytoplasmic temperature according to external conditions, in contrast to their adaptation to other environmental changes such as osmolarity or pH. Rather, cells need to adapt to new cytoplasmic temperature through mechanisms that are complex and not fully understood (Mitchell and Lampert 2000; Williams et al. 2011). Optimal temperature at which cells can proliferate is likely a polygenic trait, which makes it challenging to precisely define all contributing genes. An impact of a given gene may reflect its function in signaling, including sensing the temperature and transmitting the signal, or its role in a downstream process critical for adaptation to new temperature. Better understanding of the genetic basis for temperature adaptation is of paramount importance with various applications. For instance, it is critical for better preparation to ongoing climate change (Leducq et al. 2014; Cavicchioli et al. 2019), for improvements in biotechnology where cell-based production demands that the utilized cell culture be resistant to temperature change (Abdel-Banat et al. 2010; Matsushita et al. 2016), and in medicine where such knowledge can be leveraged to cure infections by limiting microbial growth at mammalian body temperature (Gao and Chen 2014).

Adaptation to temperature change is essential for opportunistic fungal pathogens to successfully colonize the host (Leach and Cowen 2013; de S Araújo et al. 2017). Human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans, which normally resides in the environment where it is exposed to temperatures rarely exceeding 35°C, is capable of growing at 37°C, which allows it to proliferate in immunocompromised individuals and cause deadly meningitis (Idnurm et al. 2005; Perfect 2006; Park et al. 2009). Elucidating a complex network of C. neoformans signaling pathways contributing to the adaptation to host temperature provides opportunity for development of more effective anticryptococcal drugs (Azevedo et al. 2016). Critical to growth at 37°C are pathways controlling endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-stress response and posttranscriptional reprogramming, cell wall, and membrane integrity pathways, including the Ras1-dependent pathway, Pkc1 and Mpk1-dependent MAPK signaling pathways, and the stress response pathway mediated by calcineurin (Odom et al. 1997; Brown et al. 2007; Nichols et al. 2007; Kozubowski et al. 2009; Maeng et al. 2010; Bahn and Jung 2013; Glazier and Panepinto 2014).

Cryptococcus neoformans calcineurin is a conserved serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatase that consists of a catalytic A subunit (Cna1) and a regulatory B subunit (Cnb1) (Clipstone and Crabtree 1992; Fox and Heitman 2002). Activity of calcineurin is inhibited by the immunosuppressive drugs cyclosporin A (CsA) and FK506 via binding to cyclophilins, cyclophilin A (encoded by two linked genes, CPA1 and CPA2) and FKBP12, respectively (Odom et al. 1997; Wang et al. 2001). The regulatory subunit Cnb1 is not only required for the activity of calcineurin but also mediates binding of both cyclophilin A-CsA and FKBP12-FK506 to calcineurin (Fox et al. 2001). Activation of Cna1 involves binding of Cnb1 and conformational changes in Cna1 triggered by calmodulin (Odom et al. 1997). Upon stress-activated calcium release, calcineurin dephosphorylates transcriptional activator Crz1, which promotes translocation of Crz1 into the nucleus and differential expression of numerous genes involved in stress adaptation (Lev et al. 2012; Chow et al. 2017). Interestingly calcineurin also plays Crz1-independent roles in stress response that likely involve regulation of mRNA storage and processing (Kozubowski et al. 2011; Park et al. 2016). How exactly calcineurin contributes to mRNA dynamics in C. neoformans remains unclear.

Cryptococcus neoformans mutants lacking septins Cdc3, Cdc11, or Cdc12 are viable at 25°C yet fail to proliferate at 37°C, suggesting critical role for septins in survival in the host environment (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). Septins are conserved filament-forming GTPases that contribute to cytokinesis, cell surface organization, and morphogenesis by mechanisms that remain obscure (Fung et al. 2014). The exact contribution of septins to growth of C. neoformans at 37°C is poorly defined.

Current in vitro methods to probe for the genetic contribution to growth of C. neoformans at host temperature include growth tests, either in liquid or on semisolid media, where cells lacking expression of tested genes are incubated at a specific temperature, typically 30°C, 37°C, or 39°C. Collections of single-gene deletion mutant strains constitute valuable resources that allow testing most of the nonessential protein-encoding genes (Liu et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2016, 2020). A limitation of current methods is that they do not provide an estimate of the maximum temperature the cells can tolerate in the absence of a given gene, thereafter referred to as Tmax. Identifying Tmax for each temperature-sensitive strain that carries a deletion of a specific nonessential gene may help to group identified genes according to values of Tmax and therefore may reveal previously unavailable information about gene function. Hypothetically, Tmax could be obtained by testing proliferation in a temperature gradient. Methods allowing for growth of microbial cells, including yeast cells, in a temperature gradient have been described (Landman et al. 1962; Elliott 1963; Walsh and Martin 1977; Fogel and Brunk 1998). Surprisingly though, to the best of our knowledge, such methods have not been utilized to compare temperature sensitivities among strains of a microorganism lacking specific genes, especially in the context of screening a collection of strains that lack single nonessential genes. Would a collection of mutant strains lacking specific genes involved in temperature adaptation reveal a range of temperature sensitivities, with each mutant being characterized by a specific Tmax? Or alternatively, would such a screen reveal just a few discrete values of Tmax, common to specific groups of genes? Given the polygenic character of the temperature tolerance, the first alternative is more likely. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have been published that addressed similar question with respect to any biological model.

In the present study, we designed and utilized a simple yet robust temperature gradient assay to define Tmax for a panel of 84 C. neoformans mutants lacking nonessential genes (strains that failed to grow at 37°C and/or were inhibited at 25°C in the absence of calcineurin activity in the initial screen of 4031 mutants). Forty-six knockouts exhibited a range of Tmax values that were significantly lower than the Tmax of the wild-type control. A strain lacking septin Cdc11 exhibited a relatively lowest Tmax and was synthetically lethal with the inhibition of calcineurin. To identify genetic connections with calcineurin and the septins, we examined cell morphology at 37°C or at 25°C in the absence of calcineurin activity, and growth in the presence of membrane-disrupting sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), cell wall damaging agent Congo Red, the antifungal drug fluconazole (FLC), or inhibitors of calcineurin. In addition, the temperature gradient assay was utilized under conditions that inhibit calcineurin. Selected mutants were also tested for localization of septins and synthetic interaction with deletion of septin-encoding gene CDC12. This approach allowed identification of mutants sensitive to calcineurin inhibition that escaped such identification using current growth assays and pointed to genes potentially involved in septin complex assembly. Collectively, our analysis has allowed identification of unique groups of genes that are likely functionally related, including genes that encode previously characterized proteins as well as proteins whose functions remain unknown that should help elucidating pathways essential for high temperature response in C. neoformans. We propose that the degree of temperature sensitivity, defined here as the maximum temperature a strain can grow at (Tmax), constitutes a valuable characteristic that may aid in identification of associations among genes involved in temperature adaptation.

Materials and methods

Strains, media, and chemicals

Wild-type C. neoformans, clinical strain H99, was used in this study (Perfect et al. 1980). The genetic screening was performed based on the C. neoformans nonessential gene knock out strain collections generated in the Madhani Laboratory (2015 and 2016 Madhani Plates), obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (www.fgsc.net) (Chun and Madhani 2010). Strains generated in this study are listed in Supplementary Data File. Cells were grown in liquid or semisolid (with 10% agar) yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) media (10% yeast extract, 20% peptone, 2% dextrose). To inhibit calcineurin, FK506 (PROGRAF, Astellas, Lot # 5A3284A), and cyclosporin A (CsA, LC Laboratories, Cat. No C-6000, kept as a 50 mg/ml DMSO stock) were used. FLC (Alfa Aesar, Cat. No J62015-03) was stored as 50 mg/ml DMSO stock. Congo Red was obtained from Sigma (Cat. No C6277) and SDS was obtained from J.T.Baker (Cat. No 4095-02).

Screen for temperature-sensitive mutants (growth spot assay)

A total of 42 96-well microplates containing 4031 single-gene deletion mutants (2015 and 2016 Madhani Plates, stored at −80°C) served as stock cultures utilized in the assays. Each strain was inoculated into freshly prepared 96-well microplates by transferring ∼5 µl of the stock culture into a well containing 100 µl of liquid YPD medium. Plates were then incubated overnight at 25°C with shaking. Cultures were then refreshed by transferring ∼2 µl of the overnight culture into wells of 96 well plates containing 100 µl of YPD liquid and subsequent incubation at ∼25°C with shaking for 2–3 h. Subsequently, 2 µl of cell culture of each deletion strain was spotted on semisolid YPD media (or YPD media supplemented with FK506 at 1 µg/ml) prepared in one-well microplates (OmniTray, Thermo Scientific, Cat. 242811) using a multichannel pipette. One-well microplates containing YPD were incubated at 25°C and 37°C and those containing YPD supplemented with FK506 were incubated at 25°C. After 2 days of incubation, the plates were imaged and growth of individual strains was assessed under light microscope (4× or 20× magnification). Inhibition of growth was judged based on visual inspection of images (performed by three independent evaluators) and supported by microscopic observations of strains whose growth seemed inhibited based on images of the plates. Strains that exhibited inhibition of growth in either test condition, but not the control conditions (YPD, 25°C) were recorded. The assay for growth at 37°C was performed two times for each strain, whereas the assay for growth in YPD supplemented with FK506 was performed one time.

Temperature gradient assay

Cells were preincubated in 1 ml of YPD media at 25°C overnight. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:10 with fresh YPD, grown for 2 h at 25°C, and diluted to ∼2.5 × 105 cells/ml. A total of 20 µl of cell suspension (distributed into eight pipette tips of a multichannel pipette; 2.5 µl in each tip) were distributed as a streak, perpendicular to the longer side of the one-well microplate (OmniTray) prepared with the YPD-based semisolid media. The plate always included one lane of wild-type control strain (H99) and up to seven tested strains. Even though the position on the plate had minimal impact on the results (Figure 2D), whenever possible, the positions where the three replicates of each knockout were spread on the plate were randomized. The lid of the microplate was sealed with parafilm to reduce excessive drying of the medium due to high temperature. The microplate was then placed on the top of heating block of the digital dry bath (VWR digital 2 block heater, Cat. No 131008010) with medium facing down. One-third of the plate (30 out of the total width of 86 mm) was settled on heating area with the top and sides covered with aluminum foil (to avoid heat loss), while the rest of the plate was uncovered and not in direct contact with the heating block. The dry bath temperature was set to 50°C, which established a gradient of temperature parallel to the streaked cell suspensions. Plates were imaged after 48 h. Images were processed with FIJI or ImageJ. To reduce variability in interpreting the position on the medium corresponding to the temperature where growth no longer occurred, the images were changed to binary images (as illustrated by the example in Figure 2C). A straight line, perpendicular to the long edge of the plate, was drawn extended from the edge of the plate corresponding to low temperature to the point where last visible colony was observed in the binary image. The length of the line was measured. The relative maximum temperature of growth (TmaxR) was calculated for each strain that was the percentage of the corresponding distance measured for the control wild-type strain (Figure 2C). Each strain was tested in three independent experiments and statistical analysis (One sample, one-tailed T-test, or one sample, two-tailed T-test in case of YPD media supplemented with CsA) was utilized to establish the significance of the difference between Tmax of the tested mutant strain and the Tmax of wild-type control strain that was set as 100 (TmaxR, P-value < 0.05). In addition, a Mann–Whitney U test was performed to analyze the data assuming that they are not normally distributed. Importantly, all results confirmed by the T-test as statistically significant were also significant according to the Mann–Whitney U test. On the other hand, a few results were not statistically significant according to the T-test but were classified as significant based on the Mann–Whitney U test (Supplementary Data File). We decided to focus on genes for which T-test indicated statistical significance.

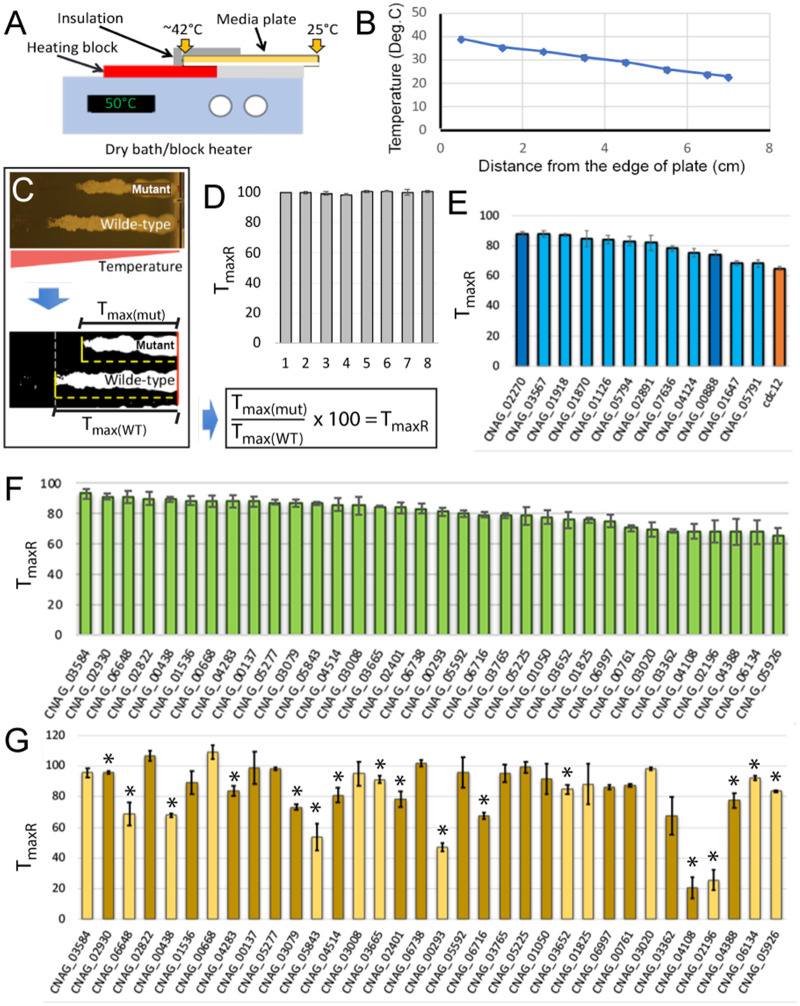

Figure 2.

Temperature gradient assay. (A) A schematic representing the gradient temperature setup. A one-well microplate was settled with one-third of the plate positioned on the top of the heating block (digital dry bath) and covered by aluminum foil for insulation. (B) Temperature of the surface of the medium was measured with an IR thermometer in eight spots along the temperature gradient and was graphed based on three replicate measurements. (C) After 48 h of incubation, the plate was imaged (an example including a wild-type control and one of the mutants is shown on top) and the image was converted to binary version to allow more consistent determination of the point corresponding to the maximum temperature of growth (Tmax). A distance corresponding to values of Tmax of the wild type and the mutant was measured and the value of relative Tmax (TmaxR) was calculated as shown. (D) Wild-type strain (H99) was streaked in eight spots on the YPD media along the temperature gradient and incubated for 48 h. TmaxR was calculated as described in C with sample #1 serving as a reference. The experiment was performed three times and the resulting TmaxR values were plotted. (E) Deletion mutant strains (sensitive to both 37°C and calcineurin inhibitor, CsA, at 25°C) for which TmaxR was significantly lower than 100 (P-value < 0.05). All strains were also sensitive to FK506, except two knockouts indicated by dark blue bars. The orange bar corresponds to cdc12Δ, which served as an additional control. (F) Deletion mutant strains (sensitive to 37°C but not sensitive to CsA at 25°C) for which TmaxR was significantly lower than 100 (P-value < 0.05). (G) Deletion mutant strains (shown in F) were subject to temperature gradient assay on media supplemented with 50 µg/ml CsA. TmaxR that were significantly different from 100 are indicated with a star (P-value < 0.05). Dark yellow/brown bars represent strains that were not sensitive to FK506 at 25°C.

Microscopy

Cells were incubated in 1 ml of YPD medium overnight at 25°C. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:10 with fresh YPD and incubated for an additional 3 h. To study the effects of 37°C and inhibition of calcineurin at 25°C, refreshed cultures were then incubated for 24 h either in YPD at 25°C (control) or at 37°C or at 25°C in YPD media supplemented with 50 µg/ml CsA (to inhibit calcineurin activity). To analyze the localization of fluorescently tagged septin proteins, cells were washed in PBS, placed on a 2% agarose patch prepared on the surface of the microscope slide, covered with cover glass, and imaged. Cells were observed under the Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) with a 100× objective or by Leica DMi8 inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a 100× objective. Images were analyzed using Zeiss ZEN lite software version 4.8.2, Leica Application Suite X3.7.2.22383, or ImageJ.

Spot growth assay

Cells were incubated in 1 ml of YPD medium overnight at 25°C. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:10 in 2 ml of YPD and cultured for 2 h at 25°C. Next, cells were washed twice in PBS and adjusted to ∼3.3 × 106 cells/ml. Three 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared in 96-well microplates. Cell suspensions (3 µl) were spotted onto plates containing YPD media (control), or YPD media supplemented with FLC (8 µg/ml), SDS (0.01%), or Congo Red (5 mg/ml). The highest number of cells that were spotted was ∼104. Cells were incubated at 25°C for 3 days prior to imaging.

Cryptococcus neoformans mating

Strains containing deletions of genes selected from the screen combined with the deletion of CDC12 or with a gene encoding Cdc3-mCherry were obtained by mating. Genetic crosses were performed between select strains originated from the Madhani Plates and either strain LK174 (cdc12Δ) or LK141 (expressing Cdc3-mCherry) (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). To induce mating, cultures of two different mating type strains (MATa and MATα), grown overnight in YPD liquid at 25°C, were mixed in 1:1 ratio in PBS and spotted onto MS mating media and incubated at 25°C in the dark for 10–15 days, as described (Xue et al. 2007). For each strain at least 40 spores, originating from at least 5 basidia, were transferred onto the YPD semisolid media with the use of SporePlay Tetrad Dissection Microscope (Singer Instruments).

In silico analysis

Genes of C. neoformans, identified in this study, were analyzed with the BLASTP (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to find homologous genes in Cryptococcus deneoformans (strain JEC21), Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Ustilago maydis, and Homo sapiens. To create a functional protein association network, the C. deneoformans homologs of genes, essential for high temperature stress identified in this study, were analyzed based on the STRING database (version 11.0). To highlight the contribution of septins in high temperature stress response, sequences of three genes encoding septins (CDC3, CDC10, and CDC12) were included in the analysis. The network was created with default settings, with a medium confidence value of 0.4, max number of interactors not higher than 5 and k-means clustering. The gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed with the PANTHER Classification System (http://pantherdb.org/). Genes were analyzed and grouped based on protein class or molecular function.

Data availability

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. Supplementary Figure S1 and data summary from this study including additional tables (a single Excel file: Stempinski_Zielinski_Supplementary_Data_file_Revised_111220) have been deposited at the GSA FigShare (https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13232663).

Supplemental material available at figshare DOI: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13232663.

Results

The goal of this study was to define genes essential for growth of C. neoformans at the temperature of the host and to reveal presently unknown functional associations between identified candidate genes. In order to facilitate identification of genes essential for growth at 37°C, we utilized a collection of single-gene deletion mutants (Madhani Plates, 4031 strains) to search for candidate genes. The collection represented a significant proportion of the 6962 C. neoformans predicted protein-coding genes (Janbon et al. 2014). We spotted the 4031 deletion mutant strains on YPD semisolid media prepared in rectangle one-well microplates. The plates were incubated at either room temperature (∼25°C) or at 37°C. In addition, we tested growth of the 4031 strains at 25°C in the presence of calcineurin inhibitor, FK506 (Odom et al. 1997). We reasoned that testing synthetic interaction with the inhibition of calcineurin will help to define the process a gene essential for growth at 37°C contributes to. For instance, if synthetic interaction with the inhibition of calcineurin was not observed, a gene that turns out essential for growth at 37°C may operate in the calcineurin pathway.

We found the growth spot assay screen suboptimal to accurately evaluate proliferation at 37°C, as two repetitions of the screen for the 4031 mutants led to variable results with respect to some deletion strains (Supplementary Data File). Nonetheless, based on this initial screen, we could narrow down our results to a pool of strains that were subject to subsequent investigations. We selected 84 mutant strains that were potentially sensitive to 37°C and/or sensitive to FK506 at 25°C, based on retarded growth observed in at least one of the two repetitions (Supplementary Data File). The 84 strains were then subject to an additional test of temperature sensitivity, the temperature gradient assay, and further phenotypic characterizations under various growth conditions, as described below and summarized in Figure 1.

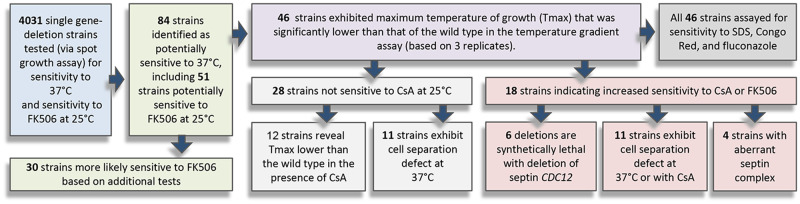

Figure 1.

A flow chart summarizing the experiments performed in this study. In the initial screen of 4031 deletion strains, 84 mutants were identified as potentially sensitive to 37°C, including 51 strains that were also potentially sensitive to inhibition of calcineurin at 25°C (on media supplemented with 1 µg/ml calcineurin inhibitor, FK506). The 84 strains were then subject to temperature gradient assay, and subsequent phenotypic characterizations as indicated.

Temperature gradient assay on drug-free YPD media

We developed a simple method to establish stable temperature gradient across semisolid medium prepared in a rectangular single-well microplate (Figure 2). The principle of obtaining the temperature gradient was as follows: the plate was positioned, with the medium facing downwards, on a standard digital dry bath/block heater (Figure 2A). Importantly, only one-third of the plate was in a direct contact with the heated block while the remaining part extended outside resting on a nonheating surface and therefore was not subject to direct heating. When the temperature in the heating block was set to 50°C, a linear temperature gradient developed across the semisolid medium ranging from the ambient temperature to ∼42°C, as established by measurements with the infrared (IR) thermometer (Figure 2B). When cells were spread on the media, along the temperature gradient, and incubated for over 2 days, colony growth was observed along the temperature gradient spanning from the edge of the plate corresponding to the lowest temperature to the point corresponding to the maximum temperature the strain can proliferate at (Tmax) (Figure 2C). For the purpose of strain comparison, we defined a relative Tmax (TmaxR) as the distance between the edge of the medium corresponding to the lowest temperature and the point where growth was no longer observed by naked eye, represented as percentage of such distance measured for the wild-type reference strain (Figure 2C). While this method did not provide specific temperature values, it did indicate Tmax of each strain relative to the wild-type strain and allowed calculations and then comparison of TmaxR values among all tested strains. A critical requirement for the assay was that each sample spread on the medium was exposed to an identical temperature gradient. To test if our assay meets this requirement, we spread the wild-type strain (H99) across the temperature gradient in eight positions. Reassuringly, after 2 days of incubation, the eight lanes revealed nearly identical pattern of growth with clearly demarcated area corresponding to Tmax. Furthermore, the calculated values of TmaxR for the seven samples relative to sample #1 (which served as a reference) were not statistically different from one another, based on three replicates (Figure 2D). We utilized the IR thermometer and estimated that the maximum temperature the wild-type (H99) strain is capable of growing at in this assay is 40.3°C ± 0.41°C (based on eight measurements).

We subjected all 84 candidate strains to the temperature gradient assay such that on each microplate, a wild-type reference strain and up to seven tested strains were spread. We considered three possible outcomes of the temperature gradient assay. (1) All or most tested strains would reveal TmaxR values within a relatively close range that is significantly lower than 100% (for instance TmaxR ∼ 80%). (2) Strains would form a few distinct groups characterized by discrete TmaxR values. (3) The TmaxR values would form a range without easily recognized discrete groups. The analysis revealed 46 strains with TmaxR that was significantly lower than that of the wild-type reference strain (Figure 2, E and F). The 46 TmaxR values formed a range from ∼66% to 93% rather than discrete groups (Figure 2, E and F, Supplementary Data File). Based on direct measurements of the temperature of the medium with the IR thermometer, we estimated that the lowest TmaxR value corresponded to Tmax of ∼32°C.

Genetic contributions to the role of calcineurin in growth at 37°C

Of the 46 strains confirmed as sensitive to 37°C by the temperature gradient assay, 20 were recorded as potentially sensitive to the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 in the initial spot growth assay screen that involved 4031 strains grown at 25°C (Supplementary Data File). For the remaining 26 strains, 19 strains were recorded as not sensitive to FK506 and the results for seven strains were not reliable (Supplementary Data File).

To further test sensitivity to the inhibition of calcineurin, all 46 mutants were subject to the temperature gradient assay while spread on media supplemented with the alternative calcineurin inhibitor, CsA (Supplementary Data File). In addition, some of the 46 strains were retested for sensitivity to FK506 or CsA either in the spot growth dilution assay, liquid growth assay, both at 25°C, or were subject to the temperature gradient assay on media containing FK506 (Supplementary Data File). We reasoned that the temperature gradient assay performed on media supplemented with CsA or FK506 could reveal phenotypic differences between strains otherwise not visible in standard growth assays.

Of the 46 temperature-sensitive strains, 12 did not grow in the presence of CsA at 25°C, including 10 strains that were confirmed for sensitivity to FK506 at 25°C (Figure 2E, Supplementary Data File). The remaining two strains, not sensitive to FK506 (lacking genes CNAG_02270 and CNAG_00888, indicated as dark blue bars in Figure 2E), are most likely not sensitive to calcineurin inhibition. Consistently, CNAG_00888 encodes calcineurin regulatory subunit Cnb1, which has been implicated in growth at 37°C (Fox et al. 2001).

The 34 temperature-sensitive strains that grew at 25°C in media supplemented with CsA, when subject to the temperature gradient assay on CsA media, exhibited various TmaxR values that did not correlate with the TmaxR values obtained when the cells were grown on regular YPD drug-free media (in the presence of calcineurin activity) (Figure 2G in comparison to Figure 2F). These TmaxR values suggested either no effect of CsA, increased, or decreased sensitivity to CsA. Specifically, two strains (both carrying deletions of genes encoding hypothetical proteins, CNAG_02822, CNAG_00668) grew at the temperature that was higher than the Tmax of the wild-type strain suggesting decreased sensitivity to CsA, although statistical significance of this difference was not robust (Figure 2G, Supplementary Data File). Average TmaxR obtained for 17 strains was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than that of the wild type (Figure 2G, Supplementary Data File). Five strains revealed TmaxR lower than wild type and clearly exhibited sensitivity to FK506, suggesting sensitivity to the inhibition of calcineurin (CNAGs: 00293, 00438, 02196, 05843, 06648) (Figure 2G, Supplementary Data File). CNAG_02196 encodes septin Cdc11, and CNAG_00293 encodes a homolog of Ras1 GTPase, previously implicated in the organization of the septin complex, consistent with our findings (Ballou et al. 2013). Four strains had TmaxR lower than 80 but exhibited no sensitivity to FK506 (CNAGs: 02401, 03079, 04108, 04388). CNAG_04388 encodes superoxide dismutase Sod2 and has been previously implicated in high temperature growth in C. neoformans (Giles et al. 2005).

Of the 38 strains whose Tmax on YPD drug-free media was not significantly different from that of the wild type, one strain (lacking CNAG_02458) did not proliferate on CsA-containing media and grew poorly on media supplemented with FK506 at 25°C, suggesting it was hypersensitive to the inhibition of calcineurin (Supplementary Data File). For 29 strains, no evidence of increased sensitivity to CsA was found, based on the temperature gradient assay (Supplementary Data File). Of the remaining eight strains with increased sensitivity to CsA, seven strains (CNAGs: 00404, 00472, 00519, 02992, 03174, 07334) were also sensitive to FK506, and two strains (CNAGs 03370, 05558) were not sensitive to FK506 (Supplementary Data File).

In summary, performing the temperature gradient assay with media containing calcineurin inhibitors has allowed identification of several strains with increased sensitivity to calcineurin inhibition that were previously missed in standard experimental approaches. An outcome of this assay combined with additional growth spot and liquid growth assays has led to identification of 14 genes that potentially operate in the calcineurin pathway as strains lacking these genes were not sensitive to at least one of the calcineurin inhibitors, FK506 or CsA (Supplementary Data File). Importantly, this group included CNAG_00888, which is a gene encoding previously characterized calcineurin regulatory subunit Cnb1 (Fox et al. 2001).

Genetic contributions to the role of septins in growth at 37°C

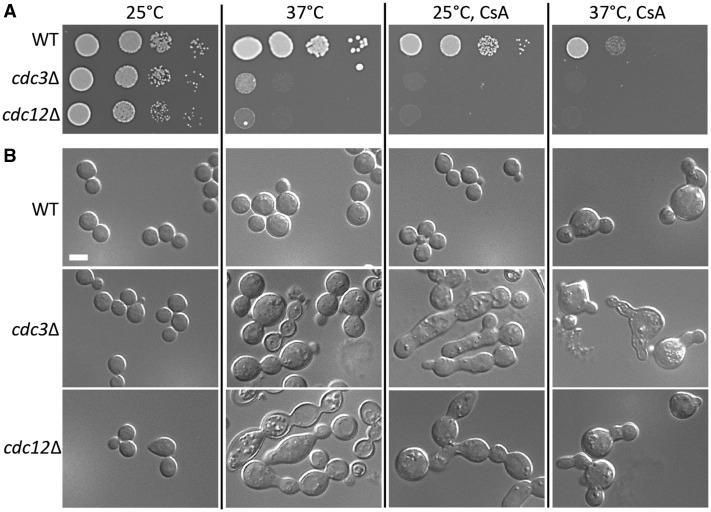

In the temperature gradient assay, a mutant lacking septin Cdc11 (CNAG_02196) was among strains with relatively lowest TmaxR values and was synthetic lethal with the inhibition of calcineurin (sensitive to both CsA and KF506) (Figure 2, F and G, Supplementary Data File). Cdc11 has been previously implicated in high temperature growth but synthetic phenotype with the inhibition of calcineurin has not been thoroughly investigated (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). A previously described mutant lacking another septin, Cdc12, when included in our assay as an additional control, revealed TmaxR that was even lower than that of cdc11Δ mutant (Figure 2E, Supplementary Data File). The exact contribution of septins to growth of C. neoformans at 37°C remains unclear, although a putative role for septins in cytokinesis may be important, given the cell separation defect observed in septin mutants at 37°C (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). We further confirmed that mutants lacking septins Cdc3 or Cdc12 are inviable at 25°C in the absence of calcineurin activity (in the presence of calcineurin inhibitor CsA) (Figure 3, Supplementary Data File). The cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ mutants proliferated in YPD medium at 25°C at a rate similar to that of the wild type and the majority of cells were morphologically similar to the wild type, consistent with previous reports (Figure 3) (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). At 37°C in drug-free media and at 25°C in the presence of the CsA, the mutant strains exhibited an aberrant morphology indicative of pleiotropic defects including inability to complete cytokinesis (Figure 3B). Interestingly, wild-type cells in the presence of CsA at 37°C were not elongated, although clearly failed to complete cytokinesis, as frequently more than one daughter was attached to the mother cell (Figure 3B). When mutant cells lacking septins were shifted to 37°C in the presence of CsA, cell elongation appeared less pronounced as compared to conditions at 25°C with CsA or 37°C in the absence of CsA (Figure 3B). These findings suggest that septins and calcineurin play nonoverlapping roles in high temperature growth.

Figure 3.

Cells lacking septins Cdc3 or Cdc12 are synthetically lethal with the inhibition of calcineurin. (A) Spot growth assays were performed with the WT (H99), the cdc3Δ (LK65), and the cdc12Δ (LK162) mutants (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). Cells were spotted on YPD medium or YPD supplemented with an inhibitor of calcineurin, CsA at 50 µg/ml. Cells were incubated for 3 days at 25°C or 37°C. (B) Strains shown in (A) were grown for 24 h in liquid YPD or YPD supplemented with 50 µg/ml CsA at 25°C or 37°C, as indicated and cellular morphology was examined. Scale bar represents 5 µm.

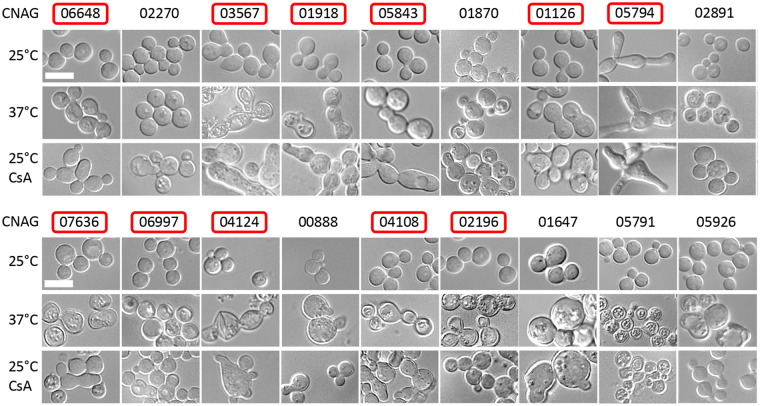

To identify other genes potentially acting with septins in high temperature growth, we selected 18 temperature-sensitive mutants, the majority of which also exhibited significantly low TmaxR on CsA-containing media, and we further characterized those strains for phenotypic similarity with the cdc11Δ mutant. Cellular morphology of the 18 strains was tested after 24 h of incubation at 37°C in YPD media or at 25°C in YPD media supplemented with CsA. Of the 18 tested strains, 11 strains (including the cdc11Δ mutant) revealed a phenotype at 37°C and/or in the presence of CsA that was indicative of cell separation defects (Figure 4). One mutant under both conditions (lacking CNAG_01647) and two mutants specifically when grown at 37°C (lacking CNAG_00888 and CNAG_05926) exhibited enlarged round morphology suggesting defects in polarity establishment (Figure 4). We also evaluated the effect of 37°C on morphology of the 28 strains that were sensitive to 37°C but not sensitive to CsA at 25°C (Figure 5). Of those 28 strains, 11 exhibited defects in cell separation (Figure 5). One mutant, a strain that lacked gene encoding Ras1 homolog (CNAG_00293), exhibited enlarged unbudded morphology characteristic of cell polarity defect, in agreement with previous findings (Figure 5) (Waugh et al. 2002).

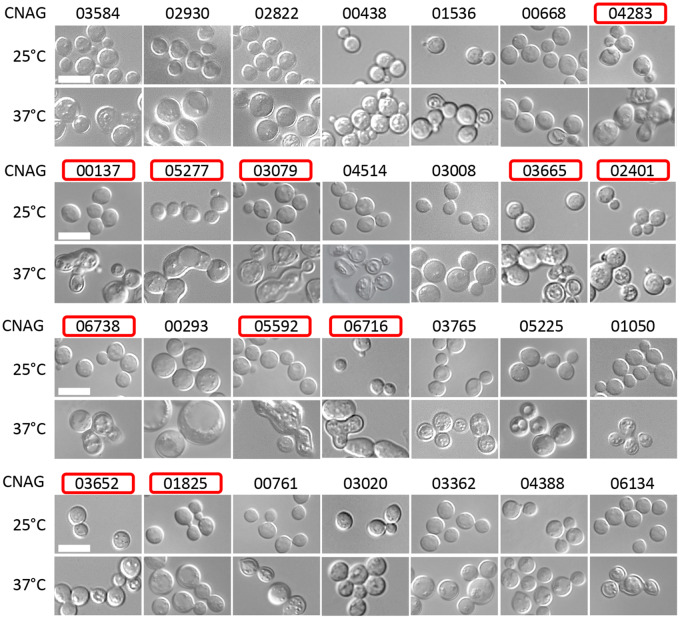

Figure 4.

Assessment of the cell morphology of the 18 mutants identified as sensitive to calcineurin inhibition at 25°C and with significant sensitivity to 37°C. Cells were examined after 24 h of growth in YPD at 25°C or 37°C or at 25°C in YPD supplemented with calcineurin inhibitor, CsA at 50 µg/ml. Strains are presented in the order from the least to the most sensitive to high temperature. Each strain is depicted by the CNAG number of the deleted gene. Red frames indicate the strains exhibiting cell separation defect under at least one of the tested conditions. Scale bar represents 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Assessment of the cell morphology of the 28 mutants identified as sensitive to 37°C but not sensitive to calcineurin inhibition at 25°C. Cells were examined after 24 h of growth in YPD at 25°C or 37°C. Strains are presented in the order from the least to the most sensitive to high temperature. Each strain is depicted by the CNAG number of the deleted gene. Red frames indicate the strains exhibiting cell separation defect at 37°C. Scale bar represents 10 µm.

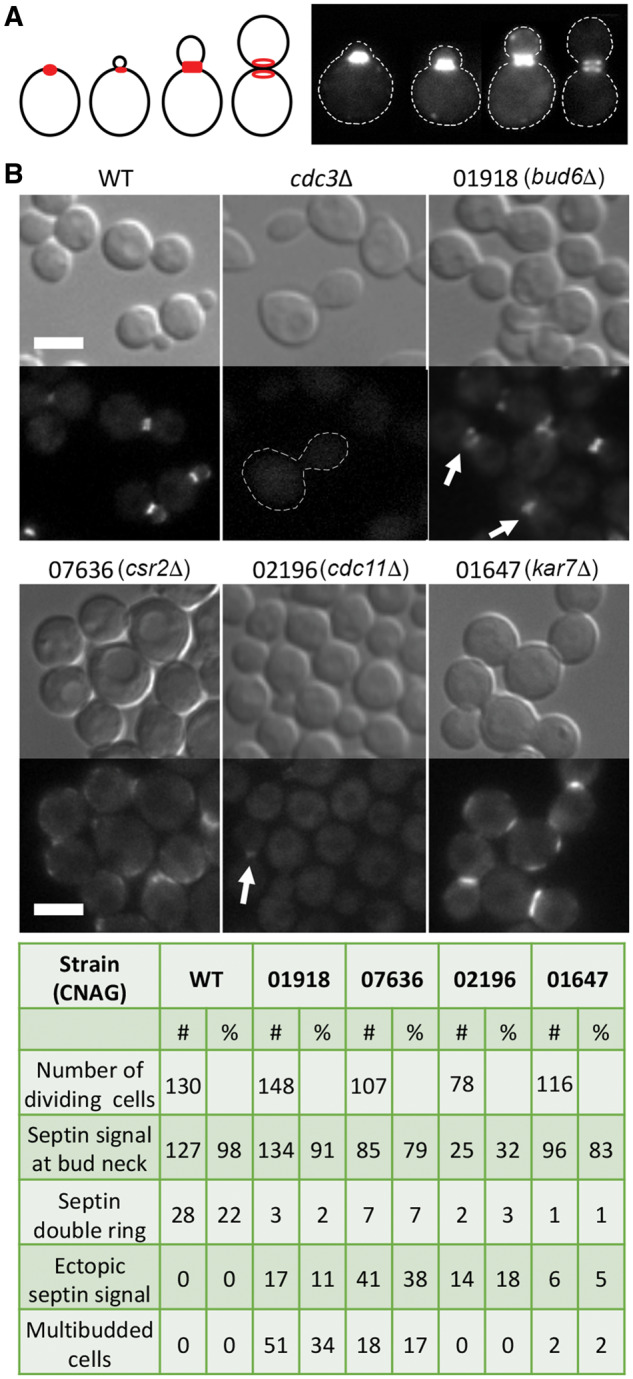

To further explore connections with the role of septins, the 18 strains that have been tested for morphology at 37°C and in the presence of CsA at 25°C (Figure 4) were utilized to introduce fluorescently tagged septin Cdc3. Expressing Cdc3-mCherry in the strain lacking CNAG_05794, which encodes RAM pathway protein Mob2 (Walton et al. 2006), was not successful. The remaining 17 genes were tested for the effect of their deletions on the localization of the septin Cdc3-mCherry. Septins in C. neoformans, similar to S. cerevisiae, localize to the incipient bud site as a patch, which arranges into a collar at the mother-bud neck. Prior to cytokinesis septin-based collar rearranges into a double ring with one ring positioned on the mother and the other ring on the daughter side of the mother-bud neck (Figure 6A) (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). Out of the 17 mutants, 4 strains revealed various defects in septin localization (Figure 6B, Supplementary Figure S1). A strain lacking chitin synthase regulator Csr2 (CNAG_07636), previously described as important for growth at 37°C, revealed an overall weaker fluorescent signal corresponding to septin complex at the mother-bud neck (Figure 6B, Supplementary Figure S1) (Banks et al. 2005). Interestingly, in csr2Δ mutant, septin Cdc3-mCherry localized to punctate structures along the perimeter of the plasma membrane, a localization rarely observed in the wild-type cells (Figure 6B, Supplementary Figure S1). The strain lacking septin Cdc11 (CNAG_02196) exhibited relatively weaker and diffused Cdc3-mCherry signal at the mother-bud neck, as compared to the wild-type control (Figure 6B, Supplementary Figure S1, arrow). Cells lacking a homolog of Bud6 (CNAG_01918) frequently contained septin signal at the mother-bud neck that appeared incomplete and often positioned on one side of the neck (Figure 6B, Supplementary Figure S1, arrows). Cells lacking Kar7 homolog (CNAG_01647), a protein implicated in nuclear fusion (Lee and Heitman 2012) and the remaining three mutants revealed reduced number of large budded cells with the characteristic double septin ring, suggesting that these genes play a role in the rearrangement of the septin complex during cytokinesis (Figure 6B, Supplementary Figure S1). Putative plasma membrane localization of Cdc3-mCherry, prominent in crs2Δ, was not observed in the remaining three mutants (Figure 6B, Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 6.

Mutants identified with the defect in the organization of the septin complex. (A) A schematic depicting organization of the septin complex (red) during the cell division cycle and representative images of the wild-type strain expressing septin Cdc3-mCherry (LK141). (B) Wild type (LK141), the cdc3Δ Cdc10-mCherry strain (LK158), and 17 deletion strains expressing Cdc3-mCherry were analyzed with fluorescence microscopy to examine septin complex organization. Cells were incubated overnight in liquid YPD medium at 25°C and subsequently refreshed in YPD for 3 h prior to imaging. In the absence of Cdc3, Cdc10-mCherry does not localize to the mother-bud neck, as shown previously (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). Four deletion strains (CNAG numbers of the deleted genes and the names of the corresponding homologs are shown) revealed defects in localization of the Cdc3-mCherry. Cdc3-mCherry often formed an aberrant discontinued signal only at one side of the mother-bud neck in cells lacking Bud6 homolog (arrow). Fluorescent signal of Cdc3-mCherry at the bud neck in cells lacking Cdc11 was relatively weak (arrow). The corresponding table summarizes quantification of cells exhibiting specific defects. See text for more details. Scale bar represents 5 microns.

To further account for possible involvement in the septin-based pathways, we tested synthetic lethal interaction with the CDC12 deletion by performing crosses between the 18 selected strains and the opposite mating type cdc12Δ mutant strain. A strain lacking CNAG_05794, which encodes Mob2 (Walton et al. 2006) could not be successfully crossed with the cdc12Δ mutant. Of the remaining 17 strains, 6 deletion mutants revealed synthetic lethal phenotype with cdc12Δ (CNAGs: 03567, 01126, 07636, 00888, 05791, 01647). Importantly, two strains that exhibited aberrant septin localization, a strain lacking septin Cdc11 and a strain lacking Bud6 homolog (CNAG_01918), were not synthetically lethal with deletion of CDC12, suggesting involvement in septin-based pathway.

Identification of additional functional connections among the candidate genes

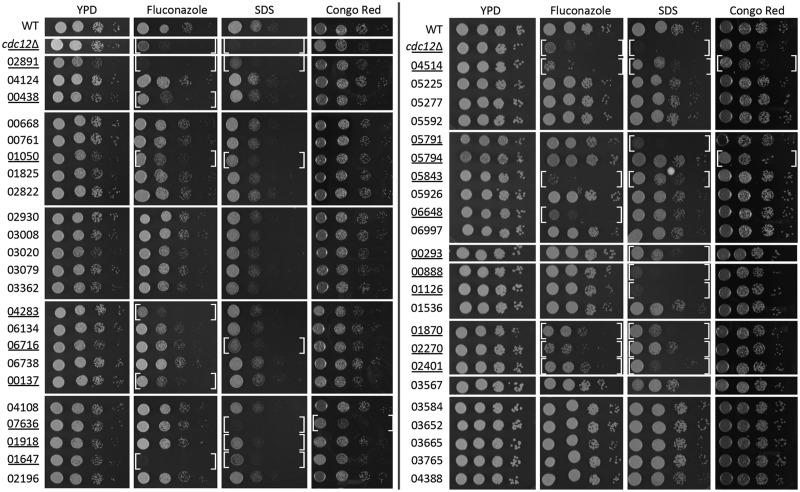

To further probe for potential functional connections between 46 genes (identified as important for high temperature growth, as shown in Figure 2), the 46 mutant strains were incubated on media supplemented with SDS, or subinhibitory concentration of FLC, conditions to which strains lacking septin Cdc12 or calcineurin are particularly sensitive (Figure 7) (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010; Chen et al. 2013). In addition, growth in the presence of cell wall disrupting agent, Congo Red, was tested, as temperature sensitivity may result from compromised cell wall integrity (Bahn and Jung 2013). Consistent with previous findings, proliferation of cells lacking Cdc12 was severely affected on media supplemented with FLC or SDS (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010; Altamirano et al. 2017). However, growth of the cdc12Δ mutant was not significantly affected by Congo Red, suggesting that septins have a minor impact on cell wall integrity. Strains lacking the CNAG_02891, which encodes ER rhodanese-like protein (Rdl2), and a strain lacking CNAG_01647, which encodes Sec66/Kar7, both exhibited significant sensitivity to SDS and FLC, and were not affected by Congo Red, similar to the cdc12Δ mutant (Figure 7). Other knockouts, which exhibited a similar pattern, although with less affected growth on SDS and/or FLC-containing media, were strains lacking CNAGs 01050, 05843, 01870, 02270, and 02401. A strain lacking CNAG_7636, which encodes chitin regulator Csr2, predicted to impact cell wall integrity (Banks et al. 2005) was hypersensitive to SDS and Congo Red but not FLC (Figure 7). Four strains were sensitive to FLC but not SDS or Congo Red (lacking CNAGs 00438, 04283, 00137, 06648). Six strains were sensitive to SDS but not FLC or Congo Red (lacking CNAGs 06716, 01918, 05791, 00293, 00888, 01126).

Figure 7.

Assessment of the sensitivity to agents that disrupt cell membrane or cell wall. A wild type (H99), a strain lacking septin Cdc12 (LK162), and 46 deletion mutant strains, identified in the temperature gradient assay as significantly more sensitive to high temperature as compared to the wild type, were incubated in liquid YPD medium at 25°C overnight, and next day refreshed in YPD at 25°C, for 3 h. Cells were serially diluted and spotted onto following semisolid media plates: YPD, YPD supplemented with 8 μg/ml FLC, 0.01% SDS, or 1 mg/ml Congo Red. Plates were photographed after 3 days of incubation at 25°C. Strains that exhibited retarded growth on any of the tested media are underlined and the white brackets indicate conditions at which growth was affected.

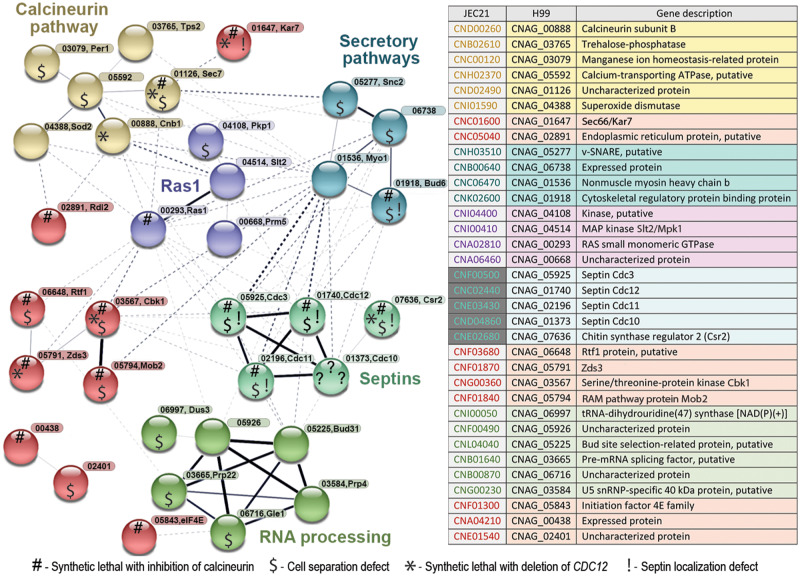

Finally, we analyzed the connections among the 46 genes, identified as important for growth at 37°C, based on the STRING database (https://string-db.org). We enriched the analysis by adding three genes encoding septins Cdc3, Cdc10, and Cdc12, to expand possible functional connections (Figure 8). Genes involved in mRNA processing formed a major cluster. Genes encoding septins were connected to the gene encoding actomyosin ring component Myo1 and genes involved in vesicle fusion. The remaining clusters contained genes involved in Ras1 signaling, calcineurin pathway, and RAM pathway. Importantly, this analysis included uncharacterized genes whose functional connections can be further investigated.

Figure 8.

A STRING analysis reveals several pathways that involve genes essential for growth at 37°C. Forty-six genes involved in high temperature growth, identified based on the temperature gradient assay, were analyzed with the STRING database with a low confidence of minimum required interaction score. Three septin genes (CDC3, CDC10, and CDC12) were added to STRING analysis to facilitate detection of interactions with the septin complex. Network edges are based on confidence of interaction and the line thickness indicates the strength of data support. Common pathways or biological processes are depicted. Symbols within the nodes represent the following features of the mutants: (1) lethality in the absence of calcineurin activity (#); (2) cell separation defect at 37°C or at 25°C when calcineurin is inhibited ($); (3) lethality with deletion of CDC12 (*); (4) septin localization defect (!). While the network was created based on the homologous genes from C. deneoformans (strain JEC21), gene names corresponding to C. neoformans (CNAG numbers) are indicated along with names of corresponding protein homologs in C. neoformans or S. cerevisiae, in cases where genes have not yet been annotated. An accompanying table indicates CNAG equivalents of the C. deneoformans genes.

Discussion

Current understanding of how individual genes influence the temperature range at which microorganisms are capable of proliferating remains incomplete. We identified 46 C. neoformans mutant strains, each lacking a nonessential protein-encoding gene, which exhibited maximum temperatures at which each of the strain can proliferate (Tmax) significantly lower than that of the wild type. The 46 relative Tmax values (TmaxR) recorded in our study ranged from 66% to 93%. This TmaxR range could stem from two possible sources: (1) Complexity of the genetic contribution to the maximum temperature a strain can grow at. With each candidate gene potentially contributing to a different aspect of temperature adaptation, the temperature range may reflect the relative contributions of the genes to high temperature growth. (2) A high variation of the phenotypic outcome resulting from the deletion of any gene that is contributing to growth at high temperature. Hypothetically, during the event a gene is deleted, cells could adapt to the deletion leading to several possible outcomes reflected by variable TmaxR values. If the latter were the case, deleting the same gene independently could result in strains with significantly different TmaxR values. To test this possibility, we selected a gene (CNAG_04283) and analyzed the consequences of deleting this gene based on independently derived deletion strains. The resulting TmaxR values for two independent deletion strains were not statistically different and yet they were significantly different as compared with the wild-type reference (data not shown). These results suggest that at least for some of the strains identified in our study, the TmaxR is a characteristic that is specific to the gene that has been deleted and does not stem from random compensatory events that would occur after the gene has been deleted. However, we cannot exclude a possibility that for some gene deletions, stochastic ploidy and/or epigenetic changes may have influenced the resulting TmaxR. Furthermore, it is possible that in some cases, deleting the same gene independently may always lead to selection of viable cells in which consistently the same specific compensatory changes allow survival under conditions the gene is deleted. Differentiating between these possibilities will require further investigations.

An important question is whether our results are consistent with other studies. While no large screen has been performed based on the temperature gradient assay, C. neoformans gene knockout collections have been utilized to identify genes essential for growth at 37°C and the effects of calcineurin inhibition (Liu et al. 2008; Brown et al. 2014). Only 5 genes from the group of 46 genes identified in our study are present in the 1200 single nonessential gene deletion collection that has been tested by Liu et al., with 3 genes identified by Liu et al. as contributing to growth at 37°C (CNAGs 02196, 04514, and 06648) and two having a minimal impact on growth at 37°C according to Liu et al., in contrast to our study (CNAGs 02930 and 05791). Another study investigated the effects of a large set of chemical compounds, including calcineurin inhibitors, on proliferation of 1448 C. neoformans knockouts (Brown et al. 2014). Of all the deletions identified in our study as causing hypersensitivity to FK506 or CsA, only nine were present in the strain collection evaluated by Brown et al. (CNAGs: 06648, 03567, 02196, 05791, 04283, 04514, 03652, 00761, 2992). Strikingly, none of these strains were classified as hypersensitive to FK506 or CsA by Brown et al. (2014). Conversely, the study by Brown et al. has revealed 24 mutants as hypersensitive to FK506. Of those 24 mutants, 13 were also evaluated in our study including 4 being classified as potentially sensitive to FK506 at 25°C (CNAGs 01149, 01172, 01612, 02073). Those four strains were not sensitive to 37°C and were not further investigated here. Our study utilized FK506 at a concentration that was ∼3 times higher than the highest concentration utilized by Brown et al., and the concentration of CsA that we applied was slightly lower (50 µg/ml vs 75 µg/ml). Furthermore, our study tested growth on rich YPD media whereas Liu et al. and Brown et al. have incubated cells on defined YNB media. These differences may have contributed to the above discrepancies in the results.

There are several limitations of our study. First, this study has been designed to reveal genes whose deletion leads to a decrease of Tmax, and could not reveal mutants resulting in increase of Tmax. For instance, a protein kinase, Sch9, suppresses C. neoformans thermotolerance and the sch9Δ mutant survives at temperatures above 41°C in contrast to the wild-type strain (Wang et al. 2004). It would be of interest to utilize temperature gradient assay to identify other genes whose deletions lead to elevated Tmax. Second, in the preliminary screen of the 4031 strains, we likely missed some genes essential for growth at 37°C due to suboptimal temperature stability in the incubator or inadequate spotting efficiency. We may have also missed genes dispensable for proliferation at 37°C yet necessary for growth at 39°C and therefore important for survival in the host. Third, the 4031 genes do not include all nonessential genes out of the predicted 6962 genes in C. neoformans (Janbon et al. 2014). Moreover, the definition of a nonessential gene is relative to the temperature at which the deletion strain has been generated. The collection of mutants we have utilized here was generated under 30°C (Chun and Madhani 2010). Therefore, genes whose deletion allows growth at temperatures lower than but not at and above 30°C were potentially missed in our study. This may explain why the lowest Tmax recorded in our study was not below 30°C. Another restriction of our study is that it did not provide the actual Tmax values. Utilization of an apparatus, capable of generating temperature gradient across semisolid media and which can precisely record temperature at each position would be critical to overcome this limitation. On the other hand, due to the fact that each strain was tested along with the wild-type control, relative values of TmaxR are a robust measure of differences between tested mutants with respect to Tmax. Another limitation is that some strains in the gene deletion collection utilized in our study may be incorrect or may exhibit suppressor phenotype. For example, our assay revealed the strain lacking CNAG_04108 as temperature sensitive, contradicting another study by Lee et al. (2016). Conversely, the study by Lee et al. (2016) found growth of strains lacking kinases Ire1 (CNAG_03670) and Utr1 (CNAG_04316) significantly affected at 37°C, whereas in our assays, mutant strains indicated as having those genes deleted, proliferated at 37°C. Therefore, following findings presented here will require further confirmation including independent gene deletion, PCR confirmation, and ideally also gene complementation. Another factor that needs to be considered and which has not been investigated here is a potential influence of media type on the Tmax.

Despite these limitations, our study has provided, for the first time, a comparison of Tmax values for a series of temperature-sensitive strains lacking nonessential genes in a microorganism. Importantly, our method is based on a relatively inexpensive and commonly available technology, which should allow meaningful comparisons to be performed in virtually any laboratory equipped with dry bath and basic molecular biology tools. Our initial screen based on traditional growth spot assay led to variable results between the two replicates. Factors contributing to variability of the results could have included not sufficiently linear temperature in the incubator, or inconsistency in spotting equal number of cells when using a multipipette. In contrast, the results obtained from the temperature gradient assay are more consistent between each of the three replicates, making this assay more reliable. Importantly, the temperature gradient assay presented here allows quantitative analysis of temperature sensitivity including statistical evaluation which contributes to reliability and reproducibility of this assay. While the three replicates included here are not sufficient for a robust statistical analysis, studies of individual genes based on the gradient assay can involve sufficient number of replicates to allow robust statistics.

What is the biological significance of our findings and the implications for further studies? Genes revealed in this study as important for high temperature growth were grouped into functional categories according to STRING database analysis, which included previously uncharacterized ORFs. We believe the temperature gradient assay constitutes a valuable complementary method that may provide important additional information about gene function. For example, differences in the TmaxR registered for deletion mutants subject to temperature gradient assay in the absence of calcineurin activity allowed for recovering information not visible otherwise at 25°C. It is important to note that the two inhibitors utilized in this study, FK506 and CsA, bind to distinct immunophilins and may have additional effects on cells that are independent of calcineurin (Wang et al. 2001; Fox and Heitman 2002; Singh-Babak et al. 2012). Thus, strains sensitive to both FK506 and CsA are more likely sensitive to inhibition of calcineurin activity, whereas those sensitive to only one of the drugs may be sensitive to inhibition of calcineurin-independent processes. A proof of principle in this case is our finding that deletion of RAS1 leads to significantly lower TmaxR as compared to the wild type under conditions of calcineurin inhibition (on media supplemented with CsA). Deletion of RAS1 is predicted to cause sensitivity to calcineurin inhibition, as Ras1 has been reported to be essential for proper septin complex assembly (Ballou et al. 2013). Inconsistent with this assumption was our initial finding that ras1Δ mutant grows robustly on media supplemented with calcineurin inhibitor CsA at 25°C. Thus, temperature gradient assay helped to resolve this inconsistency. Importantly, the temperature gradient assay revealed some uncharacterized genes exhibiting relatively low TmaxR on media supplemented with CsA and it will be of interest to investigate those uncharacterized genes for their potential connection to Ras1-dependent pathway. Conversely, the assay also revealed deletion mutants not significantly different from the wild type with respect to sensitivity to calcineurin inhibition even in the gradient assay, placing these deleted genes as potentially operating in the calcineurin pathway. In principle, the temperature gradient assay may be utilized to assess sensitivities of a series of mutants to drugs whose targets are well defined. For instance, it may be a useful tool to further resolve the apparent tolerance of C. neoformans to caspofungin, in which both calcineurin and septins were recently implicated (Pianalto et al. 2019).

Mutants lacking septin proteins were among those that revealed lowest TmaxR in the temperature gradient assay. Interestingly, deletion of CDC11, which leads to a partial defect in septin complex organization led to relatively higher Tmax values on YPD media and on media supplemented with CsA, as compared to the cdc12Δ mutant in which septin complex cannot be detected at the mother-bud neck (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). This suggests that TmaxR resulting from deletion of a gene encoding a specific septin reflects the degree to which septin complex is compromised. Assuming that Cdc11 and Cdc12 are both playing a common role in the cell as part of the septin complex with no nonoverlapping functions, this proof of principle example illustrates how robustness of a protein complex may influence the Tmax. On the other hand, mutations in nonseptin genes involved in septin complex assembly may lead to more severe effects if the gene in question is involved in other processes beyond septin assembly.

Our study revealed four genes whose absence led to misorganization of the septin complex at the mother-bud neck. The cdc11Δ mutant revealed a partial septin defect. A mutant lacking Sec66/Kar7 (CNAG_01647) exhibited a defect in septin complex reorganization during cytokinesis, which is intriguing as no other studies link Sec66/Kar7 homolog to septin organization in other fungal models. In S. cerevisiae, Sec66/Kar7 is a nonessential subunit of the Cec63 complex that forms a channel that mediates protein targeting and import into the ER (Feldheim et al. 1993). Sec66/Kar7 has been implicated in nuclear fusion in S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans, presumably by mediating translocation of relevant proteins involved in nuclear fusion into the ER and to the cytosol (Ng and Walter 1996; Lee and Heitman 2012). It is possible that among proteins transported out of the ER in Sec66-dependent manner are proteins necessary for proper septin organization. Interestingly, C. neoformans sec66Δ mutant exhibits a defect in bilateral mating where the basidiospore chain formation does not occur (Lee and Heitman 2012). This phenotype is strikingly reminiscent of the mating defect of the C. neoformans septin mutants, which fail to produce spore chains and reveal aberrant nuclear distribution within the hyphae (Kozubowski and Heitman 2010). It is possible that sporulation defect described by Lee and Heitman (2012) in the sec66Δ mutant results from inability to organize septin complex during hyphal growth. Both septin and sec66Δ mutants were sensitive to CsA and FK506 further supporting overlapping functions. On the other hand, the sec66Δ cdc12Δ double mutant could not be recovered suggesting synthetic lethality and additional nonoverlapping roles for Sec66 and septins in cell physiology. Strain lacking the Sec66/Kar7 homolog and the strain lacking Cdc12 exhibited the lowest Tmax. This is consistent with the predicted pleiotropic phenotype associated with the absence of Sec66 given the role of Sec66/Kar7 in translocation of proteins across the ER and in membrane fusion (Kurihara et al. 1994; Lee and Heitman 2012).

The third strain with a septin organization defect was a mutant lacking the homolog of Bud6 (CNAG_01918). The bud6Δ mutant exhibited incomplete septin rings at the mother-bud neck. In S. cerevisiae, Bud6 acts as a nucleation-promoting factor stimulating formin Bni1 in assembly of actin cables (Graziano et al. 2011). Another study has demonstrated that Bud6 is essential to maintain diffusion barrier for proteins associated with the ER that spans the mother-bud neck (Luedeke et al. 2005). While Bud6 depends on septins for its localization to the mother-bud neck in S. cerevisiae, it seems dispensable for septin complex organization in these species (Luedeke et al. 2005). Therefore, it is possible that the effect of BUD6 deletion on septin organization in C. neoformans is indirect, perhaps resulting from a defect in organization of actomyosin ring during cytokinesis. Interestingly, we were able to recover a bud6Δ cdc12Δ double mutant, which suggests that Bud6 and septins operate in the same pathway related to cytokinesis and/or growth at host temperature. This finding would be striking if Bud6 was needed for proper actomyosin ring organization, as S. cerevisiae cytokinesis cannot be completed in the absence of proper septin complex assembly and actomyosin ring (Ko et al. 2007). Future studies should further test the role of Bud6 in septin dynamics and reveal whether Bud6 is essential for proper assembly and dynamics of the actomyosin ring in C. neoformans.

The fourth mutant with an aberrant septin organization was a strain lacking a predicted chitin synthase regulator Csr2 (CNAG_07636) (Banks et al. 2005). Like its homolog in S. cerevisiae, Chs4, the Csr2 is predicted to stimulate chitin synthase Chs3 and link Chs3 to the septin complex at the mother-bud neck (DeMarini et al. 1997; Banks et al. 2005). Localization of septins in S. cerevisiae cells lacking Chs4 is essentially normal (DeMarini et al. 1997). The csr2Δ cells revealed localization of septin Cdc3-mCherry at the plasma membrane. One explanation for this unusual localization could be that under conditions of compromised cell wall, expected in csr2Δ cells, septins are recruited to the plasma membrane to mitigate the defect by either supporting cell wall remodeling or plasma membrane integrity. Recent studies suggest septins impact biophysical properties of membranes and it would be of interest to explore this potential novel function of septins in C. neoformans (Yamada et al. 2016; Beber et al. 2019).

In summary, our study for the first time assessed maximum temperature of growth for a series of mutants sensitive to 37°C. The results of the temperature gradient assay were combined with phenotype analysis under various conditions relevant to high temperature growth including inhibition of calcineurin. The range of Tmax values obtained for the 46 temperature-sensitive mutants confirmed a polygenic character of genetic contribution to Tmax. On the other hand, based on STRING analysis and phenotypic characterization, gene clusters contributing to high temperature growth were identified. Our analysis indicated that the temperature gradient assay provides complementary information, which when combined with comprehensive phenotypic evaluation can aid in elucidation of the genetic basis for temperature range at which microorganisms can proliferate. It remains unknown whether the relative Tmax values recorded for specific gene deletions in C. neoformans are conserved among other yeast species, including distantly related ascomycetous yeasts and future studies could address this intriguing question.

Acknowledgements

The Madhani Plates utilized in this study were generated in Madhani Laboratory at UCSF in a project supported by NIH funding (R01AI100272). We thank the laboratory of Dr. Joseph Heitman for sharing an aliquot of the FK506 reagent.

Funding

P.R.S. and L.K. were supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIHGMS) grant P20GM109094.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Literature cited

- Abdel-Banat BMA, Hoshida H, Ano A, Nonklang S, Akada R. 2010. High-temperature fermentation: how can processes for ethanol production at high temperatures become superior to the traditional process using mesophilic yeast? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 85:861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamirano S, Fang D, Simmons C, Sridhar S, Wu P, et al. 2017. Fluconazole-induced ploidy change in Cryptococcus neoformans results from the uncoupling of cell growth and nuclear division. mSphere. 2, doi:10.1128/ mSphere.00205-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo R, Rizzo J, Rodrigues ML. 2016. Virulence factors as targets for anticryptococcal therapy. J Fungi (Basel). 2: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahn YS, Jung KW. 2013. Stress signaling pathways for the pathogenicity of Cryptococcus. Eukaryot Cell. 12:1564–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou ER, Kozubowski L, Nichols CB, Alspaugh JA. 2013. Ras1 acts through duplicated Cdc42 and Rac proteins to regulate morphogenesis and pathogenesis in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003687.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks IR, Specht CA, Donlin MJ, Gerik KJ, Levitz SM, et al. 2005. A chitin synthase and its regulator protein are critical for chitosan production and growth of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 4:1902–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beber A, Taveneau C, Nania M, Tsai FC, Cicco AD, et al. 2019. Membrane reshaping by micrometric curvature sensitive septin filaments. Nat Commun. 10, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JCS, Nelson J, VanderSluis B, Deshpande R, Butts A, et al. 2014. Unraveling the biology of a fungal meningitis pathogen using chemical genetics. Cell. 159:1168–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Campbell LT, Lodge JK. 2007. Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus under stress. Curr Opin Microbiol. 10:320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli R, Ripple WJ, Timmis KN, Azam F, Bakken LR, et al. 2019. Scientists’ warning to humanity: microorganisms and climate change. Nat Rev Microbiol. 17:569–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YL, Lehman VN, Lewit Y, Averette AF, Heitman J. 2013. Calcineurin governs thermotolerance and virulence of Cryptococcus gattii. G3 (Bethesda). 3:527–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow EW, Clancey SA, Billmyre RB, Averette AF, Granek JA, et al. 2017. Elucidation of the calcineurin-Crz1 stress response transcriptional network in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun CD, Madhani HD. 2010. Applying genetics and molecular biology to the study of the human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Methods Enzymol. 470:797–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clipstone NA, Crabtree GR. 1992. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation. Nature. 357:695–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de S Araújo GR, Souza W, Frases S. 2017. The hidden pathogenic potential of environmental fungi. Future Microbiol. 12:1533–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarini DJ, Adams AE, Fares H, De Virgilio C, Valle G, et al. 1997. A septin-based hierarchy of proteins required for localized deposition of chitin in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J Cell Biol. 139:75–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RP. 1963. Temperature-gradient incubator for determining the temperature range of growth of microorganisms. J Bacteriol. 85:889–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim D, Yoshimura K, Admon A, Schekman R. 1993. Structural and functional characterization of Sec66p, a new subunit of the polypeptide translocation apparatus in the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell. 4:931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel GB, Brunk CF. 1998. Temperature gradient chamber for relative growth rate analysis of yeast. Anal Biochem. 260:80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DS, Cruz MC, Sia RA, Ke H, Cox GM, et al. 2001. Calcineurin regulatory subunit is essential for virulence and mediates interactions with FKBP12-FK506 in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 39:835–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DS, Heitman J. 2002. Good fungi gone bad: the corruption of calcineurin. Bioessays. 24:894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung KY, Dai L, Trimble WS. 2014. Cell and molecular biology of septins. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 310:289–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Chen H. 2014. Hyperthermia on skin immune system and its application in the treatment of human papillomavirus-infected skin diseases. Front Med. 8:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles SS, Batinic-Haberle I, Perfect JR, Cox GM. 2005. Cryptococcus neoformans mitochondrial superoxide dismutase: an essential link between antioxidant function and high-temperature growth. Eukaryot Cell. 4:46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazier VE, Panepinto JC. 2014. The ER stress response and host temperature adaptation in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Virulence. 5:351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano BR, DuPage AG, Michelot A, Breitsprecher D, Moseley JB, et al. 2011. Mechanism and cellular function of Bud6 as an actin nucleation-promoting factor. Mol Biol Cell. 22:4016–4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idnurm A, Bahn YS, Nielsen K, Lin X, Fraser JA, et al. 2005. Deciphering the model pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 3:753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janbon G, Ormerod KL, Paulet D, Byrnes EJ 3rd, Yadav V, et al. 2014. Analysis of the genome and transcriptome of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii reveals complex RNA expression and microevolution leading to virulence attenuation. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko N, Nishihama R, Tully GH, Ostapenko D, Solomon MJ, et al. 2007. Identification of yeast IQGAP (Iqg1p) as an anaphase-promoting-complex substrate and its role in actomyosin-ring-independent cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 18:5139–5153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozubowski L, Aboobakar EF, Cardenas ME, Heitman J. 2011. Calcineurin co-localizes with P-bodies and stress granules during thermal stress in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 10:1396–1402. doi:10.1128/EC.05087-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozubowski L, Heitman J. 2010. Septins enforce morphogenetic events during sexual reproduction and contribute to virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 75:658–675. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozubowski L, Lee SC, Heitman J. 2009. Signalling pathways in the pathogenesis of Cryptococcus. Cell Microbiol. 11:370–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara LJ, Beh CT, Latterich M, Schekman R, Rose MD. 1994. Nuclear congression and membrane fusion: two distinct events in the yeast karyogamy pathway. J Cell Biol. 126:911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landman OE, Bausum HT, Matney TS. 1962. Temperature gradient plates for growth of microorganisms. J Bacteriol. 83:463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach MD, Cowen LE. 2013. Surviving the heat of the moment: a fungal pathogens perspective. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003163.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leducq J-B, Charron G, Samani P, Dubé AK, Sylvester K, et al. 2014. Local climatic adaptation in a widespread microorganism. Proc Biol Soc. 281:20132472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KT, Hong J, Lee DG, Lee M, Cha S, et al. 2020. Fungal kinases and transcription factors regulating brain infection in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat Commun. 11:1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KT, So YS, Yang DH, Jung KW, Choi J, et al. 2016. Systematic functional analysis of kinases in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat Commun. 7:12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Heitman J. 2012. Function of Cryptococcus neoformans KAR7 (SEC66) in karyogamy during unisexual and opposite-sex mating. Eukaryot Cell. 11:783–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev S, Desmarini D, Chayakulkeeree M, Sorrell TC, Djordjevic JT. 2012. The Crz1/Sp1 transcription factor of Cryptococcus neoformans is activated by calcineurin and regulates cell wall integrity. PLoS One. 7:e51403.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu OW, Chun CD, Chow ED, Chen C, Madhani HD, et al. 2008. Systematic genetic analysis of virulence in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell. 135:174–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedeke C, Frei SB, Sbalzarini I, Schwarz H, Spang A, et al. 2005. Septin-dependent compartmentalization of the endoplasmic reticulum during yeast polarized growth. J Cell Biol. 169:897–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng S, Ko YJ, Kim GB, Jung KW, Floyd A, et al. 2010. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals novel roles of the Ras and cyclic AMP signaling pathways in environmental stress response and antifungal drug sensitivity in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 9:360–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K, Azuma Y, Kosaka T, Yakushi T, Hoshida H, et al. 2016. Genomic analyses of thermotolerant microorganisms used for high-temperature fermentations. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 80:655–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SE, Lampert W. 2000. Temperature adaptation in a geographically widespread zooplankter, Daphnia magna. J Evol Biol. 13:371–382. [Google Scholar]

- Ng DT, Walter P. 1996. ER membrane protein complex required for nuclear fusion. J Cell Biol. 132:499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CB, Perfect ZH, Alspaugh JA. 2007. A Ras1-Cdc24 signal transduction pathway mediates thermotolerance in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 63:1118–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom A, Muir S, Lim E, Toffaletti DL, Perfect J, et al. 1997. Calcineurin is required for virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 16:2576–2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, et al. 2009. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 23:525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Chow EW, Fu C, Soderblom EJ, Moseley MA, et al. 2016. Calcineurin targets involved in stress survival and fungal virulence. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect JR. 2006. Cryptococcus neoformans: the yeast that likes it hot. FEMS Yeast Res. 6:463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect JR, Lang SD, Durack DT. 1980. Chronic cryptococcal meningitis: a new experimental model in rabbits. Am J Pathol. 101:177–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianalto KM, Billmyre RB, Telzrow CL, Alspaugh JA. 2019. Roles for stress response and cell wall biosynthesis pathways in caspofungin tolerance in Cryptococcus neoformans. Genetics. 213:213–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AH, Evison LM. 1965. Studies on the biochemical basis of the minimum temperatures for growth of certain psychrophilic and mesophilic micro-organisms. J Gen Microbiol. 38:131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Babak SD, Shekhar T, Smith AM, Giaever G, Nislow C, et al. 2012. A novel calcineurin-independent activity of cyclosporin A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biosyst. 8:2575–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Uden N. 1985. Temperature profiles of yeasts. In: Rose AH, Tempest DW editors. Advances in Microbial Physiology. London: Academic Press. p. 195–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RM, Martin PA. 1977. Growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces uvarum in a temperature gradient incubator. J Inst Brew. 83:169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Walton FJ, Heitman J, Idnurm A. 2006. Conserved elements of the RAM signaling pathway establish cell polarity in the basidiomycete Cryptococcus neoformans in a divergent fashion from other fungi. Mol Biol Cell. 17:3768–3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Cardenas ME, Cox GM, Perfect JR, Heitman J. 2001. Two cyclophilin A homologs with shared and distinct functions important for growth and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO Rep. 2:511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Cox GM, Heitman J. 2004. A Sch9 protein kinase homologue controlling virulence independently of the cAMP pathway in Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr Genet. 46:247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh MS, Nichols CB, DeCesare CM, Cox GM, Heitman J, et al. 2002. Ras1 and Ras2 contribute shared and unique roles in physiology and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology. 148:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]