Abstract

In most species that reproduce sexually, successful gametogenesis requires recombination during meiosis. The number and placement of crossovers (COs) vary among individuals, with females and males often presenting the most striking contrasts. Despite the recognition that the sexes recombine at different rates (heterochiasmy), existing data fail to answer the question of whether patterns of genetic variation in recombination rate are similar in the two sexes. To fill this gap, we measured the genome-wide recombination rate in both sexes from a panel of wild-derived inbred strains from multiple subspecies of house mice (Mus musculus) and from a few additional species of Mus. To directly compare recombination rates in females and males from the same genetic backgrounds, we applied established methods based on immunolocalization of recombination proteins to inbred strains. Our results reveal discordant patterns of genetic variation in the two sexes. Whereas male genome-wide recombination rates vary substantially among strains, female recombination rates measured in the same strains are more static. The direction of heterochiasmy varies within two subspecies, Mus musculus molossinus and Mus musculus musculus. The direction of sex differences in the length of the synaptonemal complex and CO positions is consistent across strains and does not track sex differences in genome-wide recombination rate. In males, contrasts between strains with high recombination rate and strains with low recombination rate suggest more recombination is associated with stronger CO interference and more double-strand breaks. The sex-specific patterns of genetic variation we report underscore the importance of incorporating sex differences into recombination research.

Keywords: recombination, meiosis, sexual dimorphism, heterochiasmy

Introduction

Meiosis converts diploid germ cells into haploid gametes. During meiosis I, DNA crossovers (COs) aid the separation of homologous chromosomes by physically linking them and establishing tension between them on the spindle (Petronczki et al. 2003). When there are too few or too many COs, chromosome segregation can be disrupted, leading to infertility, miscarriage, and birth defects (Hassold and Hunt 2001). Recombination also shapes evolution by shuffling the combinations of genetic variants offspring inherit. Recombination affects the fates of beneficial and deleterious mutations (Fisher 1930; Hill and Robertson 1966; Felsenstein 1974) and modulates the effect of natural selection on linked neutral diversity (Maynard Smith and Haigh 1974; Begun and Aquadro 1992; Charlesworth et al. 1993; Cutter and Payseur 2013).

The role of recombination in facilitating meiotic chromosome assortment suggests that the total number of COs in a cell—the genome-wide recombination rate—is connected to organismal fitness. The dual pressures of ensuring at least one CO per chromosome and minimizing levels of DNA damage and ectopic exchange are thought to impose lower and upper thresholds on the genome-wide recombination rate (Inoue and Lupski 2002; Nagaoka et al. 2012). Yet, within these bounds, individuals from the same species can vary substantially in CO number (Kong et al. 2008; Gruhn et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2015; Johnston et al. 2016).

Sex is the most notable axis along which recombination rate varies among individuals. Broadly speaking, sexual dimorphism in the genome-wide recombination rate assumes two forms. In species such as Drosophila melanogaster, one sex completes meiosis without forming crossovers (“achiasmy”), while the other sex recombines (Haldane 1922; Huxley 1928; Burt et al. 1991). Alternatively, in most species with recombination, COs occur in both sexes but at different rates (“heterochiasmy”). In these species, females tend to recombine more than males (Bell 1982; Burt et al. 1991; Lenormand and Dutheil 2005; Lorch 2005; Brandvain and Coop 2012). In plants, heterochiasmy is correlated with the opportunity for haploid selection (Lenormand and Dutheil 2005).

Despite the recognition of differences between females and males, the extent to which sex shapes patterns of natural genetic variation in recombination rate has yet to be evaluated directly. Large-scale comparisons of variation in female recombination rate and variation in male recombination rate within species have come from populations of humans (Kong et al. 2004; Kong et al. 2008; Gruhn et al. 2013; Kong et al. 2014; Halldorsson et al. 2019), dogs (Campbell et al. 2016), cattle (Ma et al. 2015; Shen et al. 2018), and Soay sheep (Johnston et al. 2016). In these outbred populations, the role of sex and the contributions of genetic variation are difficult to separate. Evolutionary comparisons indicate that species can differ in the level and direction of heterochiasmy (Lenormand and Dutheil 2005; Brandvain and Coop 2012), but the correlation between female recombination rate and male recombination rate among closely related species remains poorly documented. Direct contrasts between the sexes across a common, diverse set of genetic backgrounds sampled within and between species would reveal the degree to which natural, heritable differences in recombination depend on sex.

Examining variation in the total number of COs in a sex-specific manner could also illuminate connections between CO number and CO positioning. Analyses of meiotic chromosome morphology in Arabidopsis thaliana, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Mus musculus suggest that the sex with more recombination usually has longer chromosome axes (Cahoon and Libuda 2019). A survey of 51 species found conserved sex differences in the recombination landscape, including telomere-biased placement of COs in males but not in females (Sardell and Kirkpatrick 2020). The degree to which a CO reduces the probability of another CO nearby (CO interference) also differs between females and males (Otto and Payseur 2019).

The house mouse, Mus musculus, is a compelling system for understanding how sex affects variation in recombination rate. Subspecies share a most recent common ancestor between 130 thousand and 420 thousand years ago (Phifer-Rixey et al. 2020), providing the opportunity to examine natural variation on recent evolutionary timescales. Wild Mus musculus belong to the same species as classical inbred strains of mice, where the molecular and cellular pathways that lead to COs have been studied extensively (Handel and Schimenti 2010; Bolcun-Filas and Schimenti 2012; Baudat et al. 2013). Immunolocalization makes it possible to characterize genome-wide recombination rates in individual males and females, as well as other meiotic traits expected to shape CO number (Koehler et al. 2002; Peters et al. 1997). The number of COs can be estimated by counting foci of the MLH1 CO-associated protein along the synaptonemal complex (Anderson et al. 1999). The length of the synaptonemal complex, the proteinaceous structure that maintains the tight alignment among homologous chromosomes (Storlazzi et al. 2010), can be estimated by visualizing the SYCP3 protein, a component of the complex’s lateral element. COs originate as double-strand breaks (DSBs) (De Massy 2013), and the number of breaks can be estimated by counting foci of strand-invasion proteins including DMC1 (Baier et al. 2014). A collection of wild-derived inbred strains of mice founded from a variety of geographic locations is available, enabling genetic variation in recombination to be profiled across the species range. Most importantly, by measuring recombination rate in individuals from the same set of wild-derived inbred strains, patterns of genetic variation in this phenotype can be directly compared in males and females.

In this paper, we report genome-wide recombination rates from both sexes in a diverse panel of wild-derived inbred strains of house mice and their relatives. We demonstrate that recombination rate shows distinct patterns of genetic variation in females and males.

Materials and methods

Mice

We used a panel of wild-derived inbred strains of house mice (Mus musculus) and related murid species to profile natural genetic variation in recombination (Table 1). Our survey included 6 strains from Mus musculus musculus, 4 strains from Mus musculus domesticus, 2 strains from Mus musculus molossinus, 2 strains from Mus musculus castaneus, and 1 strain each from Mus spicilegus, Mus spretus, and Mus caroli. We subsequently denote strains by their abbreviated subspecies and name (e.g. domesticusWSB).

Table 1.

Wild-derived inbred mouse strains surveyed for this study

| Species | Strain name | Abbreviation | Geographic origin | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. m. domesticus | G | Gough Island | Payseur Laboratory | |

| LEWES/EiJ | LEW | Lewes, Delaware | Jackson Laboratory | |

| PERC/EiJ | PERC | Peru | Jackson Laboratory | |

| WSB/EiJ | WSB | Eastern Shore, Maryland | Jackson Laboratory | |

| M. m. musculus | AST/TUA | AST | Astrakhan, Russia | BRC RIKEN |

| CZECHII/EiJ | CZECH | Slovakia | Jackson Laboratory | |

| KAZ/TUA | KAZ | Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan | BRC RIKEN | |

| PWD/PhJ | PWD | Prague, Czech Republic | Jackson Laboratory | |

| SKIVE/EiJ | SKIVE | Skive, Denmark | Jackson Laboratory | |

| TOM/TUA | TOM | Tomsk, Russia | BRC RIKEN | |

| M. m. molossinus | MOLF/EiJ | MOLF | Kyushu, Japan | Jackson Laboratory |

| MSM/MsJ | MSM | Mishima, Japan | Jackson Laboratory | |

| M. m. castaneus | CAST/EiJ | CAST | Thailand | Jackson Laboratory |

| HMI/Ms | HMI | Hemei, Taiwan | BRC RIKEN | |

| Mus spretus | SPRET/EiJ | SPRET | Cadiz, Spain | Jackson Laboratory |

| Mus spicilegus | SPI/TUA | SPI | Mt. Caocasus, Bulgaria | BRC RIKEN |

| Mus caroli | CAR | CAROLI | Thailand | BRC RIKEN |

Mice were housed at dedicated, temperature-controlled facilities in the UW-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, with the exception of mice from Gough Island, which were housed in a temperature-controlled facility in the UW-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine. Mice were sampled from a partially inbred strain of Gough Island mice, after approximately six generations of brother–sister mating. All mice were provided with ad libitum food and water. Procedures followed protocols approved by IACUC.

Tissue collection and immunohistochemistry

The same dry-down spread technique was applied to both spermatocytes and oocytes, following Peters et al. (1997) with adjustment for volumes. Spermatocyte spreads were collected and prepared as described in Peterson et al. (2019). Most mice used for MLH1 focus counts were aged between 5 and 12 weeks. Juvenile males between 12 and 15 days of age were used for DMC1 focus counts. In females, both ovaries were collected from embryos (16–21 embryonic days) or neonates (0–48 h after birth). Decapsulated ovaries were incubated in 300 µl of hypotonic solution for 45 min. In males, whole testes were incubated in 3 ml of hypotonic solution for 45 min. Fifteen microliters of cell slurry (masticated gonads) were transferred to 80 µl of 2% PFA solution. Cells were fixed in this solution and dried overnight in a humid chamber at room temperature. The following morning, slides were treated with a Photoflow wash (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA; diluted 1:200). Slides were stored at −20°C if not stained immediately. To visualize the structure of meiotic chromosomes, we used antibody markers for the centromere (CREST) and lateral element of the synaptonemal complex (SC) (SYCP3). COs were visualized as MLH1 foci. DSBs were visualized as DMC1 foci. The staining protocol followed Anderson et al. (1999) and Koehler et al. (2002). Antibody staining and slide blocking were performed in 1X antibody dilution buffer (ADB) [normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA), 1X PBS, bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)]. Following a 30-min blocking wash in ADB, each slide was incubated with 60 µl of a primary antibody master mix for 48 h at 37°C. The master mix recipe contained polyclonal anti-rabbit anti-MLH1 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA; diluted 1:50) or anti-rabbit anti-DMC1 (mix of DMC1), anti-goat polyclonal anti-SYCP3 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; diluted 1:50), and anti-human polyclonal antibody to CREST (Antibodies, Inc, Davies, CA, USA; diluted 1:200) suspended in ADB. Slides were washed twice in 50-ml ADB before the first round of secondary antibody incubation for 12 h at 37°C. Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; diluted to 1:100) and Coumarin AMCA donkey anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA; diluted to 1:200) were suspended in ADB. The last incubation of Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-goat (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; diluted 1:100) was incubated at 1:100 for 2 h at 37°C. Slides were fixed with Prolong Gold Antifade (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 24 h after a final wash in 1X PBS. Three slides of cell spreads were prepared for each mouse to serve as technical replicates for the staining protocol. Comparisons of multiple, stained slides from the same mouse showed no difference in mean MLH1 cell counts and mean cell quality. Sampled numbers of mice and cells per mouse were maximized to the extent possible given constraints on breeding and time.

Image processing

Images were captured using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with AxioLab camera and AxioVision software (Zeiss, Cambridge, UK). The number of cells imaged per mouse followed previous studies (Murdoch et al. 2010; Dumont and Payseur 2011; Wang and Payseur 2017). Preprocessing, including cropping, noise reduction, and histogram adjustments, was performed using Adobe Photoshop (v13.0). Image file names were anonymized before manual scoring of MLH1 foci or DMC1 foci using Photoshop.

Analyses

To estimate the number of COs across the genome, we counted MLH1 foci within bivalents (synapsed homologous chromosomes). MLH1 foci were counted in pachytene cells with intact and complete karyotypes (19 acrocentric bivalents and XY for spermatocytes; 20 acrocentric bivalents for oocytes) and distinct MLH1 foci. A quality score ranging from 1 (best) to 5 (worst) was assigned to each cell based on visual appearance of staining and spread of bivalents. Cells with a score of 5 were excluded from the final analysis. Distributions of MLH1 focus count were visually inspected for normality (Supplementary Figure S1). When outliers for MLH1 focus count were found during preliminary analysis, counts were confirmed on the original images. MLH1 foci located on the XY in spermatocytes were excluded from counts.

In addition to MLH1 focus counts, we measured several traits to further characterize the recombination landscape. To estimate the number of DSBs, a minority of which lead to COs, the number of DMC1 foci was counted in cells from a single male from each of a subset of strains (molossinusMSM, musculusPWD, musculusKAZ, domesticusWSB, domesticusG). SC morphology and CREST focus number were used to stage spermatocytes as early zygotene or late zygotene.

To measure bivalent SC length, two image analysis algorithms were used. The first algorithm estimates the total (summed) SC length across bivalents for individual cells (Wang et al. 2019). The second algorithm estimates the SC length of individual bivalents (Peterson et al. 2019). Both algorithms apply a “skeletonizing” transformation to synapsed chromosomes that produces a single, pixel-wide “trace” of the bivalent shape. Total SC length per cell and individual bivalent SC length were both quantified from pachytene cell images (Peterson et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019).

To reduce algorithmic errors in SC isolation, outliers were visually identified at the mouse level and removed from the dataset. Mouse averages were calculated from cell-wide total SC lengths in 3,195 out of 3,871 cells with MLH1 focus counts. The DNA CO algorithm (Peterson et al. 2019) isolates single, straightened bivalent shapes, returning SC length, location of MLH1 foci, and location of CREST (centromere) foci. The algorithm substantially speeds the accurate measurement of bivalents, but it sometimes interprets overlapping bivalents as single bivalents. In our dataset, average proportions of bivalents per cell isolated by the algorithm ranged from 0.48 (molossinusMSM male) to 0.72 (musculusKAZ female). From the total set of pachytene cell images, 10,213 bivalent objects were isolated by the algorithm. Following manual curation, 9,569 single-bivalent observations remained. The accuracy of the algorithm is high compared to hand measures after this curation step (Peterson et al. 2019). The curated single-bivalent data supplemented our cell-wide MLH1 count data with MLH1 foci counts for single bivalents. Proportions of bivalents with the same number of MLH1 foci were compared across strains using a chi-square test.

To account for confounding effects of sex chromosomes from pooled samples of bivalents, we also considered a reduced dataset including only bivalents with SC lengths falling within the 1st quartile in cells with at least 17 of 20 single-bivalent measures. This “short bivalent” dataset included the four or five shortest bivalents within a cell, thus excluding the X bivalent in oocytes. A total of 699 short bivalents were isolated from 102 oocytes and 42 spermatocytes. Although this smaller dataset had decreased power, it offered a more comparable set of single bivalents to compare between the sexes. A “long bivalent” dataset was formed from those bivalents falling within the 4th quartile in SC lengths per cell. A total of 703 long bivalents were isolated from 102 oocytes and 42 spermatocytes.

As a surrogate for CO interference, the distance (in SC units) between MLH1 foci (inter-focal distance; IFDraw) was measured for those single bivalents containing two MLH1 foci. A normalized measure of interference (IFDnorm) was computed by dividing IFDraw by SC length on a per-bivalent basis.

We used a series of statistical models to interpret patterns of variation in the recombination traits we measured (Table 2). We used mouse average value (across cells) as the dependent variable in all analyses. We first constructed a linear mixed model (M1) using lmer() from the lmer4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R (v3.5.2) (R Core Team 2015 ). In this model, strain was coded as a random effect, with significance evaluated using a likelihood ratio test implemented with exactRLRT() in RLRsim (Scheipl et al. 2008). Subspecies, sex, and their interaction were coded as fixed effects, with significance evaluated using a chi-square test comparing the full and reduced models [drop1() and anova()] (Bates et al. 2015). The hierarchical nature of the data meant that nesting of levels across observations was implicit (i.e. mouse within strain, strain within subspecies) and not explicitly coded. We used the subspecies effect to quantify divergence between subspecies and the (random) strain effect to quantify variation within subspecies in a sex-specific manner. In separate analyses using model M1, we considered mouse averages as dependent variables for each of the following traits: MLH1 focus count, total SC length, single-bivalent SC length, IFDraw, IFDnorm, and average MLH1 focus position (for single-focus bivalents). Four additional linear models containing only fixed effects (M2–M5) (Table 2) were used to further investigate results obtained from model M1.

Table 2.

Summary of linear models used for statistical analyses

| Model | Dataset(s) | Dependent variable(s) | Fixed effects | Random effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Females and males from 8 strains | Mouse average |

Subspecies Sex Subspecies*Sex |

Strain |

| M2 | Females and males from 8 strains | Mouse average |

Subspecies Sex Strain Subspecies*Sex Subspecies*Strain Sex*Strain |

|

| M3 | Females and males from 8 strains | Mouse average |

Sex Strain Sex*Strain |

|

| M4 | Females from 8 strains | Female mouse average |

Subspecies Strain Subspecies*Strain |

|

| M4 |

Males from 12 strains |

Male mouse average |

Subspecies Strain Subspecies*Strain |

|

| M5 | Females from 8 strains | Female mouse average |

Strain |

|

| M5 | Males from 12 strains | Male mouse average | Strain |

Data availability

Data files, analysis scripts, and other Supplementary materials are available in FigShare and in a public github repository (https://github.com/petersoapes/MeioticRecombSexualDimorphism). Because of their large sizes, image files are hosted on the NSF CyVerse (https://de.cyverse.org/de/) and can be shared upon request.

Supplementary material is available at figshare DOI: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13281512.

Results

Genome-wide recombination rate shows distinct patterns of genetic variation in females and males

We used counts of MLH1 foci per cell to estimate genome-wide recombination rates in 17 wild-derived inbred strains sampled from four subspecies of house mice (M. musculus domesticus, M. m. musculus, M. m. molossinus, and M. m. castaneus) and three other species of Mus (M. spretus, M. spicilegus, and M. caroli). Mean MLH1 focus counts for 170 mice (across a total of 1,832 spermatocytes and 1,535 oocytes) were quantified (Table 3). Due to poor breeding and low cell numbers, mice from the two M. m. castaneus strains and the M. caroli strain were excluded from further analyses.

Table 3.

Summary statistics for MLH1 focus count, SC length, MLH1 focus position, and MLH1 inter-focal distance

| Species | Strain | Sex | MLH1 focus count |

SC length (total) |

SC length (short bivalents) |

SC length (long bivalents) |

Normalized MLH1 focus position (1CO) |

Interfocal distance (2CO) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Cells | Mean | SE | Cells | Mean | SE | No. | Mean | SE | No. | Mean | SE | No. | Mean | SE | No. | Mean (norm.) | SE (norm.) | Mean (raw) | SE (raw) | |||

| M. m. domesticus | WSB | Female | 14 | 201 | 24.72 | 1.03 | 235 | 1,722.57 | 73.25 | 50 | 73.89 | 9.87 | 49 | 128.53 | 13.61 | 539 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 186 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 53.71 | 3.83 |

| Male | 10 | 192 | 23.52 | 0.64 | 169 | 1,338.08 | 35.54 | 15 | 48.55 | 6.46 | 15 | 86.4 | 10.25 | 470 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 107 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 47.94 | 4.51 | ||

| G | Female | 12 | 319 | 28.02 | 0.78 | 347 | 2,081 | 60.35 | 96 | 81.85 | 6.58 | 97 | 130.94 | 9.62 | 457 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 242 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 60.25 | 3.35 | |

| Male | 11 | 232 | 23.68 | 0.56 | 204 | 1,466.35 | 35.78 | 18 | 53.85 | 5.94 | 17 | 92.7 | 7.5 | 566 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 122 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 52.41 | 4.24 | ||

| LEW | Female | 9 | 147 | 26.41 | 1.16 | 163 | 1,927.13 | 71.36 | 52 | 83.05 | 10.38 | 52 | 138.47 | 13.52 | 413 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 236 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 57.25 | 6.05 | |

| Male | 7 | 163 | 24.05 | 0.59 | 172 | 1,417.21 | 29.59 | 5 | 56 | 7 | 5 | 99 | 8.57 | 330 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 77 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 52.15 | 4.81 | ||

| PERC | Male | 1 | 26 | 21.81 | 0.42 | 28 | 1,448.36 | 23.22 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| M. m. musculus | PWD | Female | 15 | 223 | 25.82 | 0.93 | 206 | 1,925.6 | 91.36 | 142 | 75.72 | 8.56 | 146 | 123.49 | 9.82 | 667 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 277 | 0.5 | 0.04 | 58.22 | 5.76 |

| Male | 8 | 161 | 28.31 | 0.67 | 118 | 1,578.35 | 46.71 | 28 | 60.07 | 5.57 | 26 | 100.95 | 6.71 | 337 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 274 | 0.6 | 0.02 | 59.72 | 2.39 | ||

| SKIVE | Female | 1 | 32 | 25.94 | 0.55 | 37 | 1,883.86 | 64.66 | 9 | 73 | 8.71 | 9 | 124.11 | 11.89 | 122 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 42 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 65.88 | 3.20 | |

| Male | 5 | 189 | 26.24 | 0.43 | 145 | 1,413.92 | 27.57 | 12 | 60.31 | 10.2 | 12 | 102.06 | 2.81 | 398 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 215 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 59.69 | 3.00 | ||

| KAZ | Female | 9 | 184 | 25.57 | 0.84 | 187 | 1,912.95 | 78.17 | 81 | 80.78 | 6.85 | 84 | 140.21 | 14.83 | 351 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 128 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 62.45 | 7.40 | |

| Male | 11 | 202 | 23.61 | 0.61 | 219 | 1,483.61 | 34.45 | 44 | 57.41 | 5.78 | 45 | 98.4 | 5.53 | 502 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 84 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 48.03 | 4.31 | ||

| TOM | Male | 1 | 5 | 25.6 | 1.54 | 14 | 1,630.5 | 35.98 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| AST | Male | 1 | 29 | 24.9 | 0.48 | 29 | 1,730.55 | 23.78 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| CZECH | Male | 3 | 62 | 22.19 | 0.51 | 91 | 1,548.61 | 30.32 | 13 | 61.54 | 6.22 | 13 | 104.24 | 6.44 | 179 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 50 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 51.5 | 6.15 | |

| M. m. molossinus | MSM | Female | 14 | 299 | 27.71 | 0.84 | 321 | 1,845.35 | 63.99 | 39 | 75.69 | 8.43 | 39 | 132.12 | 13.88 | 361 | 0.57 | 0.02 | 159 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 60.39 | 4.10 |

| Male | 4 | 124 | 30.15 | 0.61 | 106 | 1,746.92 | 37.05 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 0.44 | NA | 44 | NA | ||

| MOLF | Female | 1 | 21 | 27.62 | 0.92 | 34 | 1,699.21 | 58.91 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Male | 6 | 119 | 23.24 | 0.62 | 148 | 1,537.02 | 29.65 | 16 | 62.31 | 6.48 | 14 | 97.86 | 6.11 | 325 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 96 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 48.04 | 4.09 | ||

| M. m. castaneus | CAST | Female | 1 | 1 | 26 | NA | 1 | 1,928 | NA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Male | 1 | 16 | 21.88 | 0.55 | 19 | 1,332.42 | 31.65 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| HMI | Male | 4 | 44 | 24.00 | 0.41 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| M. spretus | SPRET | Female | 3 | 7 | 26.27 | 3.18 | 7 | 2,486.44 | 343.18 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Male | 4 | 75 | 24.58 | 0.64 | 79 | 1,543.15 | 28.68 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| M. spicilegus | SPI | Female | 7 | 101 | 27.36 | 1.03 | 106 | 2,349.31 | 115.66 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Male | 5 | 136 | 24.88 | 0.58 | 140 | 1,543.03 | 22.96 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| M. caroli | CAROLI | Male | 2 | 57 | 27.00 | 0.40 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

For inter-focal distance, “norm.” = distance between MLH1 foci divided by SC length.

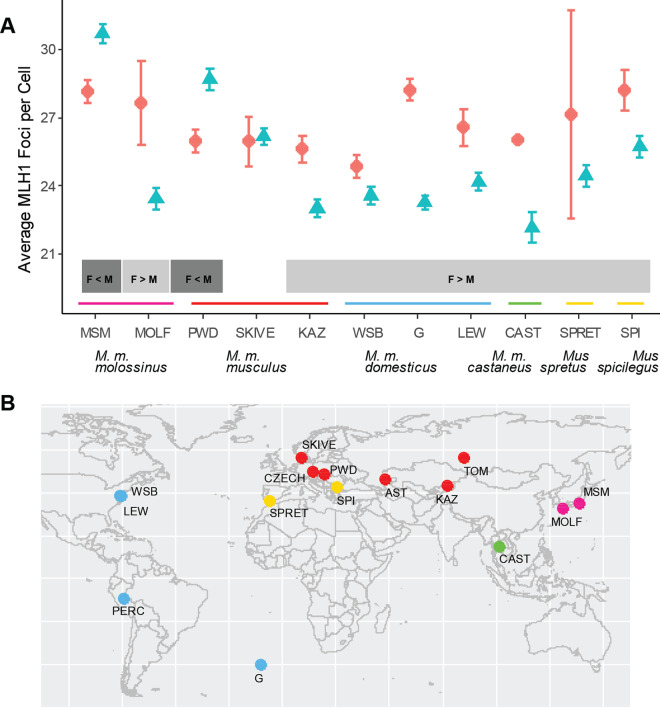

Graphical comparisons reveal sex-specific patterns in the distribution of genome-wide recombination rate (Figure 1). First, MLH1 focus counts differ between females and males in most strains. Second, the difference in MLH1 focus counts between the sexes varies among strains. Although most strains show more MLH1 foci in females, two strains (musculusPWD and molossinusMSM) exhibit higher counts in males, demonstrating that the direction of heterochiasmy varies within subspecies. The range of MLH1 focus counts among strains is higher in males than in females. Strain mean MLH1 focus counts from females and males are uncorrelated (Spearman’s = 0.08; P = 0.84) across the set of strains.

Figure 1.

MLH1 focus counts in house mice and their relatives. (A) Strain mean MLH1 focus counts (± 2 standard errors). Females = red circles; males = blue triangles. Gray boxes below points indicate the direction of heterochiasmy (which sex recombines more; F = female, M = male) for each strain. (B) Map of approximate locations where progenitors for the surveyed strains of Mus musculus, M. spretus, and M. spicilegus were sampled. Colors match subspecies/species designations in (A). Strains shown in (B) but not in (A) did not have sufficient data from females to characterize sex differences.

To further partition variation in recombination rate, we fit a series of linear models to mean MLH1 focus counts from 137 house mice from M. m. domesticus, M. m. musculus, and M. m. molossinus (Table 2; detailed results available in Supplementary Table S1). Strain, sex, subspecies, and sex*subspecies each affect MLH1 focus count in a linear mixed model (M1; strain (random effect): P < ; sex: P = 3.64 × ; subspecies: P = 9.69 × ; subspecies*sex: P = 1.8 × ).

The effect of subspecies is no longer significant in a model treating all factors as fixed effects (M2; musculus P = 0.24, molossinus P = 0.1), highlighting strain and sex as salient variables. Two strains exhibit strong effects on MLH1 focus count (M3; domesticusG P = 1.78 × ; domesticusLEW P = 0.02), with sex–strain interactions involving three strains (M3; domesticusG P < ; molossinusMSM P < ; musculusPWD P = 3.87 × ).

In separate analyses of males (M4; n = 71), three strains disproportionately shape MLH1 focus count (as observed in Figure 1): musculusPWD (P = 3.6 × ; effect = 6.11 foci), molossinusMSM (P = 6.3 × ; effect = 6.91), and musculusSKIVE (P = 8.22 × ; effect = 4.04). These three strains point to substantial changes in the genome-wide recombination rate in spermatocytes. In females (M4; n = 76), three strains significantly affect MLH1 focus count: domesticusG (P = 8.7 × ; effect = 3.3), molossinusMSM (P = 2.43 × ; effect = 2.99), and domesticusLEW (P = 0.03; effect = 1.69). Strain effect sizes in females are modest in magnitude compared to those in males, consistent with greater between-strain variation among males.

Together, these results demonstrate that the genome-wide recombination rate varies in a highly sex-specific manner across this collection of wild-derived strains.

Females and males differ consistently in SC length, CO position, and CO interference

We asked whether sex differences in SC length, CO position, and CO interference track sex differences in genome-wide recombination rate across strains.

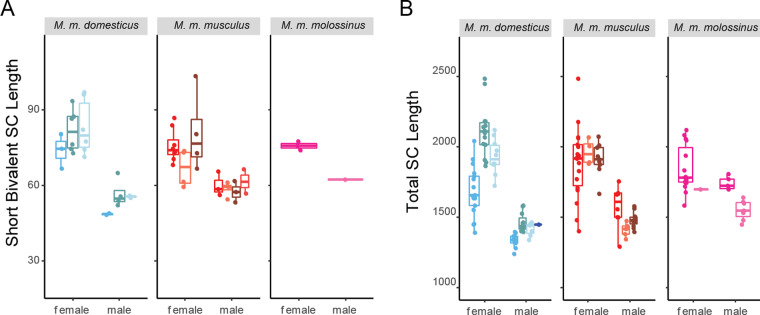

In all strains except one, females have longer SCs than males, whether SC length was estimated as the total length across bivalents or as the length of short bivalents (Figure 2, Table 3; t-tests; all P < 0.05, except short bivalents in musculusSKIVE, P = 0.11). Among short bivalents (to which the female X bivalent does not contribute), female to male ratios of mouse mean SC length range from 1.26 (musculusPWD) to 1.52 (domesticusWSB) across strains. That females have longer SCs is further supported by models that include covariates, which identify sex as the most consistently significant effect for total SC length (M1: P = 2.56 × ; M2: P = 2.56 × ; M3: P = 2.56 × ) (Supplementary Table S1) and short bivalent SC length (M1: P = 1.12 × ; M2: P < ; M3: P < 1.33 × ) (Supplementary Table S1). The existence of subspecies and strain effects on total SC length and short bivalent SC length indicates that SC length varies among strains and among subspecies.

Figure 2.

Sex differences in SC length in three subspecies of house mice. (A) Mouse average SC length of short bivalents. Whiskers indicate interquartile range. (B) Mouse average total (summed) SC length.

We used normalized positions of MLH1 foci along bivalents with a single focus to compare CO location while controlling for differences in SC length. In all strains, MLH1 foci tend to be closer to the telomere in males (Table 3) (mean normalized position in males: 0.68; mean normalized position in females: 0.56; paired t-test; P = 8.49 × ). Sex is also the strongest determinant of MLH1 focus position in models we tested (M1: P = 2.82 × ; M2: P = 3.96 × ; M3: P = 3.96 × ) (Supplementary Table S1).

We used inter-focal distances to compare CO interference on bivalents with two MLH1 foci. Males have longer normalized mean inter-focal distances (IFDnorm) than females in seven out of eight strains (Table 3, Supplementary Figure S2; t-tests; P < 0.05), with only musculusKAZ showing no difference (P = 0.33). Models treating IFDnorm as the dependent variable also show stronger interference in males, with sex being the most significant variable (M1: P = 9.08 × ; M2: P = 0.01; M3: P = 0.01) (Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, raw mean inter-focal distances (IFDraw) are generally longer in females (Table 3); there is statistical support for a sex effect in this direction when strain is treated as a random effect (M1, P = 0.026) but not when strain is treated as a fixed effect (M2, P = 0.26; M3, P = 0.26) (Supplementary Table S1). Visualization of normalized MLH1 foci positions on bivalents with two COs (Supplementary Figure S2) further suggests that interference distances vary more in females than in males, and that males display a stronger telomeric bias in the placement of the distal CO.

In summary, males have shorter SCs, greater telomere-bias in CO placement, and stronger CO interference than females. These characteristics do not closely track sex differences in genome-wide recombination rate across strains.

Variation in genome-wide recombination rate among males is dispersed across bivalents, connected to CO interference, and associated with DSB number

To conduct a preliminary search for features of the recombination landscape associated with transitions in genome-wide recombination rate, we assigned strains to two groups based on recombination rate in males. MolossinusMSM, musculusPWD, and musculusSKIVE were assigned to the “high-recombination” group; domesticusWSB, domesticusLEW, domesticusG, musculusKAZ, and molossinusMOLF were assigned to the “low-recombination” group. The features we considered were proportions of bivalents with different numbers of COs, SC length, and DSB number.

Ninety-six percent of single bivalents in our pooled dataset (n = 9,569) have either one or two MLH foci (Supplementary Figure S3). The proportions of single-focus (1CO) bivalents vs. double-focus (2CO) bivalents distinguish high-recombination strains from low-recombination strains (Supplementary Figure S3). High-recombination strains are enriched for 2CO bivalents at the expense of 1CO bivalents: proportions of 2CO bivalents are 0.33 in musculusSKIVE, 0.44 in musculusPWD, and 0.51 in molossinusMSM. Following patterns in the genome-wide recombination rate, male musculusPWD and male molossinusMSM have 2CO proportions that are more similar to each other than to strains from their own subspecies (chi-square tests; musculusPWD vs. molossinusMSM: P = 0.37; musculusPWD vs. musculusKAZ: P = 1.23 × ; molossinusMSM vs. molossinusMOLF: P = 2.34 × ). These results suggest that variation among strains in the genome-wide recombination rate reflects changes in CO number across multiple bivalents.

SC length does not consistently differentiate high-recombination strains from low-recombination strains. Whereas high-recombination strains as a group have significantly greater total SC length than low-recombination strains (t-test; P = 0.01), this difference disappears when SC lengths for the reduced short bivalent dataset (P = 0.84) or long bivalent dataset (P = 0.19) are considered. In a model with total SC length as the dependent variable (M4), the two subspecies effects are significant (M. m. musculus: P = 3.95 × ; M. m. molossinus: P = 3.33 × ), but there are also strain-specific effects (Supplementary Table S1). In models with SC lengths of short and long bivalents as dependent variables, several subspecies and strain effects reach significance (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S1), but they are not consistent across models. These results suggest that variation among strains in genome-wide recombination rate is not strongly associated with changes in SC length.

High-recombination strains have greater inter-focal distances than low-recombination strains (t-test; IFDnorm: P = 3.3 × ; IFDraw: P = 2.1 × ). The main distinction in IFDnorm distributions is an enrichment of IFDnorm values under 0.3 in low-recombination strains (Supplementary Figure S2). Percentages of IFDnorm values that fall below 0.3 range from 8.2% (domesticusG) to 16% (musculusKAZ) in low-recombination strains, whereas high-recombination strains show percentages below 4% (0%, 3.1%, and 1.5% for musculusSKIVE, molossinusMSM, and musculusPWD, respectively). There is no difference between high-recombination and low-recombination strains in the average position of MLH1 foci on bivalents with a single focus (t-test; P = 0.7). These results suggest that variation among strains in genome-wide recombination rate is connected to changes in CO interference.

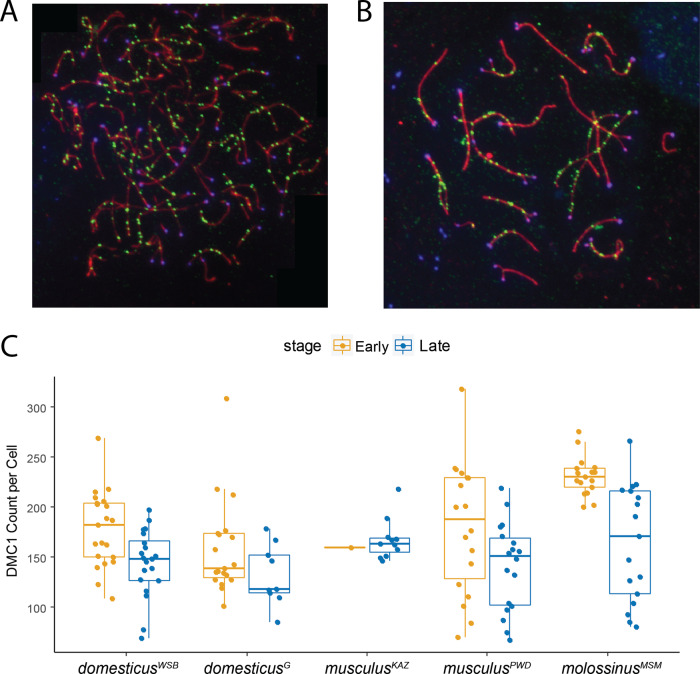

To measure the number of DSBs, we counted foci of the DMC1 strand-invasion protein in prophase spermatocytes. DMC1 foci were counted in a total of 76 early zygotene and 75 late zygotene spermatocytes from two high-recombination strains (musculusPWD and molossinusMSM) and three low-recombination strains (musculusKAZ, domesticusWSB, and domesticusG) (Table 4). High-recombination strains have significantly more DMC1 foci than low-recombination strains in early zygotene cells (Figure 3; t-test; P < ). In contrast, the two strain groups do not differ in DMC1 foci in late zygotene cells (t-test; P = 0.66). Since DSBs are repaired as either COs or non-crossovers (NCOs), the ratio of MLH1 foci to DMC1 foci can be used to estimate the proportion of DSBs designated as COs. High-recombination strains and low-recombination strains do not differ in the MLH1/DMC1 ratio, whether DMC1 foci were counted in early zygotene cells or late zygotene cells (t-test; P > 0.05). These results are consistent with variation in genome-wide recombination rate being primarily determined by processes that precede the CO/NCO decision in mice (Baier et al. 2014).

Table 4.

DMC1 focus counts in males from five strains of house mice

| Recombination group | Strain | Early zygotene |

Late zygotene |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | DMC1 mean | MLH1:DMC1 ratio | Cells | DMC1 mean | MLH1:DMC1 ratio | ||

| Low | domesticus WSB | 21 | 177.76 | 0.14 | 20 | 144.25 | 0.17 |

| domesticus G | 19 | 158.16 | 0.15 | 9 | 131.78 | 0.18 | |

| musculus KAZ | 1 | 159.00 | 0.15 | 11 | 167.36 | 0.14 | |

| High | musculus PWD | 18 | 180.22 | 0.16 | 18 | 140.78 | 0.21 |

| molossinus MSM | 17 | 231.00 | 0.14 | 17 | 164.41 | 0.19 | |

Figure 3.

DMC1 focus counts in males from three subspecies of house mice. (A) Example early zygotene spermatocyte spread. SYCP3 stained in red, CREST (centromeres) stained in blue, and DMC1 stained in green. (B) Example late zygotene spermatocyte spread. (C) Boxplots of DMC1 focus counts for five strains of house mice. Whiskers indicate interquartile range.

In summary, variation among strains in genome-wide recombination rate in males is dispersed among bivalents, associated with CO interference, and connected to DSB number.

Discussion

By comparing recombination rate in females and males from the same diverse set of genetic backgrounds within and between subspecies of house mice, we identified sex as a primary factor governing variation in this fundamental meiotic trait. Recombination rate differences are more pronounced in males than females. Because inter-strain divergence times are identical for the two sexes, this observation raises the possibility that the genome-wide recombination rate evolves faster in males. More generally, changes in recombination rate are decoupled in females and males. These disparities are remarkable given that recombination rates for the two sexes were measured in identical genetic backgrounds (other than the number and identity of sex chromosomes).

At the genetic level, the sex-specific patterns we documented suggest that some mutations responsible for natural variation in recombination rate have dissimilar phenotypic effects in the two sexes. A subset of the genetic variants associated with genome-wide recombination rate within populations of humans (Kong et al. 2004, 2008, 2014; Halldorsson et al. 2019), Soay sheep (Johnston et al. 2016), and cattle (Ma et al. 2015; Shen et al. 2018) appear to show sex-specific properties, including opposite effects in females and males. Furthermore, inter-sexual correlations for recombination rate are weak in humans (Fledel-Alon et al. 2011) and Soay sheep (Johnston et al. 2016). Crosses between the strains we surveyed could be used to identify and characterize the genetic variants responsible for recombination rate differences in house mice (Dumont and Payseur 2011; Wang and Payseur 2017; Wang et al. 2019). These variants could differentially affect females and males at any step in the recombination pathway.

Another implication of our results is that the connection between recombination rate and fitness differs between males and females. Little is known about whether and how natural selection shapes recombination rate in nature (Dapper and Payseur 2017; Ritz et al. 2017). Samuk et al. (2020) recently used a quantitative genetic test to conclude that an 8% difference in genome-wide recombination rate between females from two populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura was caused by natural selection. Applying similar strategies to species in which both sexes recombine, including house mice, would be a logical next step toward understanding how selection affects recombination rate differently in females and males.

Population genetic models have been built to explain the common observation of sexual dimorphism in the number and placement of COs (Brandvain and Coop 2012; Sardell and Kirkpatrick 2020). Modifier models predicted that lower recombination rates in males will result from haploid selection (Lenormand 2003) or sexually antagonistic selection on coding and cis-regulatory regions of genes (Sardell and Kirkpatrick 2020). Another modifier model showed that meiotic drive could stimulate female-specific evolution of the recombination rate (Brandvain and Coop 2012). These models do not readily explain the sex-specific patterns of variation in genome-wide recombination rate we observed.

Our measurement of additional meiotic characteristics known to influence recombination did not identify strong correlates of sex differences in genome-wide recombination rate across strains. We found that male mice have shorter SCs, greater telomeric bias in CO location, and stronger CO interference than females, even in strains with higher recombination in males. The within-subspecies variation in the direction of heterochiasmy we discovered indicates recombination differences between females and males can evolve rapidly and positions house mice as a good system for understanding the determinants of heterochiasmy.

Our comparisons between males from high-recombination strains and males from low-recombination strains suggest that CO interference and the number of DSBs could contribute to natural variation in genome-wide recombination rate. The notion that stronger interference associates with higher genome-wide recombination rate is supported by differences between breeds of cattle (Ma et al. 2015). In contrast, mammalian species with stronger interference tend to exhibit lower genome-wide recombination rates (Segura et al. 2013; Otto and Payseur 2019). Our observation that males from high-recombination strains have proportionally more DSBs than males from low-recombination strains matches previous findings from other strains of house mice (Baier et al. 2014). Determining how CO interference and DSB number modulate natural variation in genome-wide recombination rate will require mechanistic studies.

Our conclusions are accompanied by several caveats. First, MLH1 foci only identify interfering COs (Holloway et al. 2008). Although most COs belong to this class (Holloway et al. 2008), our approach likely underestimated genome-wide recombination rates. A second limitation is that our investigation of CO locations was confined to the relatively low resolution possible with immunolocalization. Positioning COs with higher resolution could reveal additional patterns. Finally, the panel of inbred lines we surveyed may not be representative of recombination rate variation within and between subspecies of house mice. We considered most available wild-derived inbred lines, but house mice have a broad geographic distribution. Nevertheless, we expect our primary conclusion that recombination rate varies in a sex-specific manner to be robust to geographic sampling because differences between females and males exist for the same set of inbred strains.

While the evolutionary, cellular, and molecular causes of sex differences in recombination remain mysterious (Lenormand et al. 2016; Cahoon and Libuda 2019), our conclusions have implications for a wide range of recombination research. For biologists uncovering the cellular and molecular determinants of recombination, our results suggest that mechanistic differences between the sexes could vary by genetic background. For researchers examining natural variation in recombination, our findings indicate that sex-specific comparisons are crucial. For theoreticians building evolutionary models of recombination, different fitness regimes and genetic architectures in females and males should be considered. Elevating sex as a primary determinant of recombination would be a promising step toward integrating knowledge of genetic mechanisms with evolutionary patterns to understand recombination rate variation in nature.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Francisco Pelegri for generous assistance with microscopy. We thank Karl Broman and Cécile Ané for advice on analyses. We thank Beth Dumont, Michael Kartje, and Alexandre Blanckaert for comments on the manuscript. A.L.P. thanks the Meiosis in Quarantine organizers and presenters for stimulating talks.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH grants R01GM120051 and R01GM100426 to B.A.P. A.L.P. was partly supported by NIH T32GM007133.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Literature cited

- Anderson LK, Reeves A, Webb LM, Ashley T.. 1999. Distribution of crossing over on mouse synaptonemal complexes using immunofluorescent localization of mlh1 protein. Genetics. 151:1569–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier B, Hunt P, Broman KW, Hassold T.. 2014. Variation in genome-wide levels of meiotic recombination is established at the onset of prophase in mammalian males. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S.. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Soft. 67:48. [Google Scholar]

- Baudat F, Imai Y, De Massy B.. 2013. Meiotic recombination in mammals: localization and regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 14:794–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun DJ, Aquadro CF.. 1992. Levels of naturally occurring DNA polymorphism correlate with recombination rates in D. melanogaster. Nature. 356:519–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G. 1982. The Masterpiece of Nature: The Evolution and Genetics of Sexuality. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolcun-Filas E, Schimenti J.. 2012. Genetics of meiosis and recombination in mice. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 298:179–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandvain Y, Coop G.. 2012. Scrambling eggs: meiotic drive and the evolution of female recombination rates. Genetics. 190:709–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt A, Bell G, Harvey PH.. 1991. Sex differences in recombination. J Evol Biol. 4:259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon CK, Libuda DE.. 2019. Leagues of their own: sexually dimorphic features of meiotic prophase 1. Chromosoma. 128:199–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CL, Bhérer C, Morrow BE, Boyko AR, Auton A.. 2016. A pedigree-based map of recombination in the domestic genome. G3 (Bethesda). 6:3517–3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Morgan M, Charlesworth D.. 1993. The effect of deleterious mutations on neutral molecular variation. Genetics. 134:1289–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutter AD, Payseur BA.. 2013. Genomic signatures of selection at linked sites: unifying the disparity among species. Nat Rev Genet. 14:262–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapper AL, Payseur BA.. 2017. Connecting theory and data to understand recombination rate evolution. Phil Trans R Soc B. 372:20160469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Massy B. 2013. Initiation of meiotic recombination: how and where? Conservation and specificities among eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 47:563–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont BL, Payseur BA.. 2011. Evolution of the genomic recombination rate in murid rodents. Genetics. 187:643–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. 1974. The evolutionary advantage of recombination. Genetics. 78:737–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA. 1930. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fledel-Alon A, Leffler EM, Guan Y, Stephens M, Coop G, et al. 2011. Variation in human recombination rates and its genetic determinants. PLoS One. 6:e20321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruhn JR, Rubio C, Broman KW, Hunt PA, Hassold T.. 2013. Cytological studies of human meiosis: sex-specific differences in recombination originate at, or prior to, establishment of double-strand breaks. PLoS One. 8:e85075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane J. 1922. Sex ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. J Gen. 12:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Halldorsson BV, Palsson G, Stefansson OA, Jonsson H, Hardarson MT, et al. 2019. Characterizing mutagenic effects of recombination through a sequence-level genetic map. Science. 363:eaau1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handel MA, Schimenti JC.. 2010. Genetics of mammalian meiosis: regulation, dynamics and impact on fertility. Nat Rev Genet. 11:124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T, Hunt P.. 2001. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat Rev Genet. 2:280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WG, Robertson A.. 1966. The effect of linkage on limits to artificial selection. Genet Res. 8:269–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway JK, Booth J, Edelmann W, McGowan CH, Cohen PE.. 2008. MUS81 generates a subset of mlh1-mlh3–independent crossovers in mammalian meiosis. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley J. 1928. Sexual difference of linkage in Gammarus chevreuxi. J Gen. 20:145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Lupski JR.. 2002. Molecular mechanisms for genomic disorders. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 3:199–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston SE, Bérénos C, Slate J, Pemberton JM.. 2016. Conserved genetic architecture underlying individual recombination rate variation in a wild population of Soay sheep (Ovis aries). Genetics. 203:583–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler KE, Cherry JP, Lynn A, Hunt PA, Hassold TJ.. 2002. Genetic control of mammalian meiotic recombination. I. Variation in exchange frequencies among males from inbred mouse strains. Genetics. 162:297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Barnard J, Gudbjartsson DF, Thorleifsson G, Jonsdottir G, et al. 2004. Recombination rate and reproductive success in humans. Nat Genet. 36:1203–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Thorleifsson G, Frigge ML, Masson G, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. 2014. Common and low-frequency variants associated with genome-wide recombination rate. Nat Genet. 46:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, Masson G, Helgason A, et al. 2008. Sequence variants in the rnf212 gene associate with genome-wide recombination rate. Science. 319:1398–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand T. 2003. The evolution of sex dimorphism in recombination. Genetics. 163:811–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand T, Dutheil J.. 2005. Recombination difference between sexes: a role for haploid selection. PLoS Biol. 3:e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand T, Engelstädter J, Johnston SE, Wijnker E, Haag CR.. 2016. Evolutionary mysteries in meiosis. Phil Trans R Soc B. 371:20160001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch P. 2005. Sex differences in recombination and mapping adaptations. Genetica. 123:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, O'Connell JR, VanRaden PM, Shen B, Padhi A, et al. 2015. Cattle sex-specific recombination and genetic control from a large pedigree analysis. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith J, Haigh J.. 1974. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet Res. 23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch B, Owen N, Shirley S, Crumb S, Broman KW, et al. 2010. Multiple loci contribute to genome-wide recombination levels in male mice. Mamm Genome. 21:550–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka SI, Hassold TJ, Hunt PA.. 2012. Human aneuploidy: mechanisms and new insights into an age-old problem. Nat Rev Genet. 13:493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP, Payseur BA.. 2019. Crossover interference: shedding light on the evolution of recombination. Annu Rev Genet. 53:19–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters AH, Plug AW, van Vugt MJ, Boer PD.. 1997. Short communications: a drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res. 5:66–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AL, Miller ND, Payseur BA.. 2019. Conservation of the genome-wide recombination rate in white-footed mice. Heredity. 123:442–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronczki M, Siomos MF, Nasmyth K.. 2003. Un menage a quatre: the molecular biology of chromosome segregation in meiosis. Cell. 112:423–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phifer-Rixey M, Harr B, Hey J.. 2020. Further resolution of the house mouse (Mus musculus) phylogeny by integration over isolation-with-migration histories. BMC Evol Biol. 20:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

- Ritz KR, Noor MA, Singh ND.. 2017. Variation in recombination rate: adaptive or not? Trends Genet. 33:364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuk K, Manzano-Winkler B, Ritz KR, Noor MA.. 2020. Natural selection shapes variation in genome-wide recombination rate in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Curr Biol. 30:1517–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardell JM, Kirkpatrick M.. 2020. Sex differences in the recombination landscape. Am Nat. 195:361–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheipl F, Greven S, Kuechenhoff H.. 2008. Size and power of tests for a zero random effect variance or polynomial regression in additive and linear mixed models. Comput Stat Data Anal. 52:3283–3299. [Google Scholar]

- Segura J, Ferretti L, Ramos-Onsins S, Capilla L, Farré M, et al. 2013. Evolution of recombination in eutherian mammals: insights into mechanisms that affect recombination rates and crossover interference. Proc R Soc B. 280:20131945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Jiang J, Seroussi E, Liu GE, Ma L.. 2018. Characterization of recombination features and the genetic basis in multiple cattle breeds. BMC Genomics. 19:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi A, Gargano S, Ruprich-Robert G, Falque M, David M, et al. 2010. Recombination proteins mediate meiotic spatial chromosome organization and pairing. Cell. 141:94–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RJ, Dumont BL, Jing P, Payseur BA.. 2019. A first genetic portrait of synaptonemal complex variation. PLoS Genet. 15:e1008337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RJ, Payseur BA.. 2017. Genetics of genome-wide recombination rate evolution in mice from an isolated island. Genetics. 206:1841–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data files, analysis scripts, and other Supplementary materials are available in FigShare and in a public github repository (https://github.com/petersoapes/MeioticRecombSexualDimorphism). Because of their large sizes, image files are hosted on the NSF CyVerse (https://de.cyverse.org/de/) and can be shared upon request.

Supplementary material is available at figshare DOI: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13281512.