Abstract

The assimilation of inorganic sulfate and the synthesis of the sulfur-containing amino acids methionine and cysteine is mediated by a multibranched biosynthetic pathway. We have investigated this circuitry in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans, which is phylogenetically intermediate between the filamentous fungi and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In S. cerevisiae, this pathway is regulated by a collection of five transcription factors (Met4, Cbf1, Met28, and Met31/Met32), while in the filamentous fungi the pathway is controlled by a single Met4-like factor. We found that in C. albicans, the Met4 ortholog is also a core regulator of methionine biosynthesis, where it functions together with Cbf1. While C. albicans encodes this Met4 protein, a Met4 paralog designated Met28 (Orf19.7046), and a Met31 protein, deletion, and activation constructs suggest that of these proteins only Met4 is actually involved in the regulation of methionine biosynthesis. Both Met28 and Met31 are linked to other functions; Met28 appears essential, and Met32 appears implicated in the regulation of genes of central metabolism. Therefore, while S. cerevisiae and C. albicans share Cbf1 and Met4 as central elements of the methionine biosynthesis control, the other proteins that make up the circuit in S. cerevisiae are not members of the C. albicans control network, and so the S. cerevisiae circuit likely represents a recently evolved arrangement.

Keywords: genetics, transcription factor, methionine biosynthesis, rewiring, regulatory complexes

Author summary

Candida albicans regulates its methionine biosynthetic pathways using the transcription factors Met4 and Cbf1. This circuitry appears more complex than that of filamentous fungi, which use orthologs of the Met4 transcription factor, but lack versions of Cbf1, but is considerably less complex than that of S. cerevisiae, which requires two transcription complexes, involving Cbf1 and Met31/32 as DNA-binding modules, and Met4 and the Met4 ortholog Met28 as co-activators, to regulate Met biosynthesis. Although C. albicans contains Met31/32 and Met28 orthologs, they do not appear to be linked to regulation of the methionine circuit. Thus, the phylogenetic progression from filamentous fungi to S. cerevisiae is characterized by the increasing complexity of the regulators, although the structural elements of the pathways are fundamentally the same.

Introduction

Methionine occupies a central role in metabolism and growth control in fungi. It is synthesized by the methionine (Met) biosynthesis pathway, also known as the sulfur assimilation pathway (Hebert et al. 2011). This pathway is regulated by a number of signals, including sulfur-containing compounds and amino acids, cadmium, arsenite, zinc, and potentially the diauxic shift (Kuras et al. 2002; Barbey et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2010).

The transcriptional regulation of the genes encoding this methionine metabolic circuitry has been investigated in a number of fungi. The simplest circuits, found in the filamentous fungi, appear to be controlled by a single transcription factor. These regulators are members of the basic leucine zipper class of transcription factors, contain highly similar DNA-binding domains, and are orthologs of the Met4 protein of S. cerevisiae. These include the Cys3 protein of N. crassa and the MetR protein of A. nidulans. In A. nidulans and its close relatives (A. fumigatus, A. niger, A. terreus, A. oryzae, and P. rubens), a gene duplication event has given rise to two paralogs, MetR and MetZ, that are both part of sulfur assimilation control (Piłsyk et al. 2015). Between these two paralogs, MetR can be considered most likely the direct ortholog of Met4 based on synteny and the overall level of sequence identity. These two paralogs are predicted to form dimers of MetR-MetR, MetR-MetZ, and MetZ-MetZ and bind to the palindromic sequence 5′-ATGRYRYCAT-3′ (Piłsyk et al. 2015).

A highly sophisticated circuitry regulating the methionine biosynthesis has been identified in S. cerevisiae and its close relatives (Bram and Kornberg 1987; Baker et al. 1989; Baker and Masison 1990; Thomas and Surdin-Kerjan 1997; Blaiseau and Thomas 1998; Kaiser et al. 2006). In S. cerevisiae, the Met4 protein associates with at least four other transcription factors, the basic helix-loop-helix protein Cbf1, the basic leucine zipper protein Met28, and two paralogous zinc finger transcription factors, Met31 and Met32. Met4 generates the central transactivating activity in these complexes but depends on the DNA binding activity of either Cbf1 or Met31/32 for promoter recruitment, potentially due to an insertion event which disrupted the structure of the DNA-binding leucine zipper module of the Met4 protein.

In S. cerevisiae, the basic leucine zipper protein Met28 also does not appear to independently bind DNA but has been shown to enhance promoter binding of the Cbf1–Met4 complex (Kuras et al. 1997). Cbf1 recognizes the sequence TCACGTG whereas Met31 and Met32 recognize AAACTGTG. Interestingly, the co-activators Met4 and Met28 also show a binding affinity to the so-called recruitment motif “RYAAT” (Siggers et al. 2011), and thus the association of Cbf1 and Met32 to their respective binding sites appears to be facilitated by Met4 and Met28.

The entire sulfur assimilation circuitry has not been as extensively studied in the Candida (CTG) clade. Here, we have investigated transcriptional regulation of sulfur metabolism in Candida albicans to establish the structure of the regulatory circuitry. This circuit represents a transition between the simple Met4 superfamily member core regulator found in the filamentous fungi, and the highly sophisticated complex of Cbf1, Met4, Met28, and Met32/31 found in S. cerevisiae.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

Sequences of genes MET4, MET28, MET32, and CBF1 were obtained from the Candida Genome Database (CGD- http://www.candidagenome.org/) and the Saccharomyces Genome Database (https://www.yeastgenome.org/). Gene orthogroup assignments for all predicted protein-coding genes across 23 Ascomycete fungal genomes were obtained from the Fungal Orthogroups Repository (Wapinski et al. 2007) maintained by the Broad Institute (broadinstitute.org/regev/orthogroups).

DNA sequence motifs were identified using the Web-based motif-detection algorithm MEME (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/intro.html; Bailey et al. 2015). For more stringent motif identification, we used MAST hits with an E value of <50. An E value of 500 corresponds roughly to a P-value of 0.08 in our analysis, and an E value of 50 roughly corresponds to a P-value of 0.008. We also used AME (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme), which identifies known motifs throughout the Candida upstream sequences.

Protein domains and linear motifs were detected from each individual TF protein sequence using INTERPROSCAN, PFAM, and ELM motif definitions.

Strains and culture conditions

For general growth and maintenance of the strains, the cells were cultured in fresh YPD medium (1% w/v yeast extract, 2% w/v Bacto peptone, 2% w/v dextrose, and 80 mg/L uridine with the addition of 2% w/v agar for solid medium) at 30°C. For methionine auxotrophy, we used synthetic dextrose (SD) medium (0.67% w/v yeast nitrogen base, 0.15% w/v amino acid mix without methionine, 0.1% w/v uridine, 2% w/v dextrose, and 2% w/v agar for solid media).

Gene knockout using CRISPR

All C. albicans mutants were constructed in the wild type strain CaI4. The protocol used for the CRISPR-mediated knockout of MET4, MET28, and MET32 was adapted from (Vyas et al. 2015); we used URA3 replacements in our study. CRIPSR-mediated knockouts used the lithium acetate method of transformation with the modification of growing transformants overnight in liquid YPD at room temperature after removing the lithium acetate-PEG. C. albicans transformants were selected for on SD URA-plates.

Activation of Met4, Met28, and Met32

For the activation module, the ACT1 promoter and VP64 were amplified by PCR and homology was created by primer extension such that there is a restriction site of restriction enzyme MluI in between ACT1 and VP64. After this, the C-terminus of the VP64 cassette was cloned into the multiple cloning site where we can add the DNA binding domains of respective transcription factors. The pCIPACT and the ligated Act1-VP64-MCS were digested with Hind III and were ligated using T4 DNA ligase. This ligated CIPACT-VP64 plasmid was transformed into E. coli using the calcium chloride method.

Plasmids extracted from colonies that were determined to have the guide sequence successfully cloned in were then used to transform C. albicans using a lithium acetate transformation protocol. pCIPACT1 was linearized by StuI-HF digest, and 1–2 μg of the linearized plasmid was used in the transformation. C. albicans transformants were selected on SD URA-plates.

RNA seq analysis

The CaMet4, CaMet28, CaMet32, and SC5143 strain cultures were grown in YPD overnight at 30°C, diluted to OD600 of 0.1 in YPD at 30°C, and then grown to an OD600 of 0.8–1.2 on a 220-rpm shaker. Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy minikit protocol, and RNA quality and quantity were determined using an Agilent bioanalyzer. Paired-end sequencing (150 bp) of extracted RNA samples was carried out at the Quebec Genome Innovation Center located at McGill University using an Illumina miSEQ sequencing platform. Raw reads were pre-processed with the sequence-grooming tool cutadapt version 0.4.1 (Martin 2011) with the following quality trimming and filtering parameters (“–phred33 –length 36 -q 5 –stringency 1−e 0.1”). Each set of paired-end reads was mapped against the C. albicans SC5314 haplotype A, version A22 downloaded from the Candida Genome Database (CGD) (http://www.candidagenome.org/) using HISAT2 version 2.0.4. SAM tools were then used to sort and convert SAM files. The read alignments and C. albicans SC5314 genome annotation were provided as input into StringTie v1.3.3 (Pertea et al. 2015), which returned gene abundances for each sample. Raw and processed data have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al. 2002).

Data availability

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. Strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Plasmids and primers used with their respective sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Supplementary Figure S1 which consist of the promoters of methionine genes across the fungal phylogeny of the candidate Met4 motif 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ and the new potential Met4 recognition motif of the CUG clade 5ʹ CAACTCCAAR 3ʹ. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data are accessible through GEO Series accession number: GSE162171. Supplemental material available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13326395.

Results

Orthologs of methionine biosynthesis regulators in C. albicans

In the ascomycetes, key methionine regulating TFs have different names, such as Met4 in S. cerevisiae, MetR in A. nidulans and Cys3 in N. crassa, but they are structurally and functionally orthologous. A binding target for this class of transcription factors, 5′-ATGRYRYCAT-3′, has been identified that is conserved among the filamentous fungi (Li and Marzluf 1996). In S. pombe, the equivalent TF, Zip1, appears rewired and is involved in a cadmium-responsive checkpoint pathway (Harrison et al. 2005) rather than in methionine biosynthesis. We found two proteins in C. albicans that showed strong structural similarities to this Met4 class of TFs; Orf19.5312 (designated CaMet4) and Orf19.7046 (designated Met28). Thus it appears, similar to the situation in A. nidulans, that the CUG clade has had a duplication of the basal MET4 gene leading to two paralogs, MET4 and MET28.

The Met4 protein of C. albicans is 385 amino acids long, with a leucine bZIP domain (aa303–aa354) that includes a specific DNA binding region (aa308—aa322) (Figure 1). Among the orthologs, CaMet4 is intermediate in size between the A. nidulans MetR of 294 amino acids, and the S. cerevisiae Met4 of 672 amino acids. The well-studied ScMet4 contains multiple domains in addition to the DNA binding region; these include an activation domain (AD), a ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM), an inhibitory region required for repression of Met4 activity by methionine (IR), an auxiliary domain required to fully relieve IR mediated repression (AUX), and a protein–protein interaction domain that binds Met31 and Met32 (INT). We searched for these domains in AnMetR, ScMet28, CaMet28, CaMet4, and NcCys3. CaMet4 shows considerable similarity to ScMet4, and even though the overall protein is almost half the size we were able to identify a candidate activation domain, a UIM region, and the B-zip region (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree. (A) The tree is constructed based on the sequence similarities of Met4 and Met28 across the fungal kingdom. A block diagram showing all the domains of the transcription factors. (B) The sequence alignment of subdomain that are highlighted by star with respective color shows that the disrupted B-zip domain, AUX and INT domain are present only in S. cerevisiae and K. lactis clade whereas in the rest of fungi complete B-Zip domain is conserved.

CaMet28 shows limited similarity with ScMet28 or ScMet4; although it is essentially the same length as ScMet28 and has the characteristic BZip domain, overall CaMet28 shows the most similarity with MetR of A. nidulans. In particular, the DNA-binding domains of CaMet28 and MetR were highly conserved (Figure 1), suggesting the possibility that CaMet28 could recognize a 5′-ATGRYRYCAT-3′ motif in promoter regions of Candida genes. Using Meme-suit online tool, we screened for this motif in the 1000 bp upstream regions of all the open reading frames of the C. albicans genome, and found only 12 genes that have this exact sequence in their promoters; these genes are not involved in any obvious common cellular function, and none are implicated in methionine biosynthesis. This result suggests that Met28 may not be involved in the control of the Met regulon of C. albicans.

Deletion of the MET4 and MET28 genes in C. albicans suggests Met4 is regulating methionine biosynthesis

The two alleles of MET4 were deleted from the prototrophic strain SC5314 using the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Vyas et al. 2015). The MET4 deleted strain was somewhat slow-growing compared to the wild type in rich YPD medium. When grown on media lacking methionine, the MET4 deleted strain was unable to grow (Figure 2A), suggesting that MET4 deletion inhibits methionine biosynthesis in C. albicans and makes cells dependent on supplemented methionine. We were unable to construct a MET28 homozygous deleted strain using the same approach, although heterozygotes were easy to obtain. Previously, it was reported that MET28 disruptants were not obtained by the UAU1 method (Segal et al. 2018), which suggests that MET28 might be an essential gene in C. albicans.

Figure 2.

Activation and deletion of Met4 and Met32 in C. albicans. (A) Methionine starvation of strain SC5314, Met4-deleted strain and Met32 deleted strain. The Met4 deleted strain shows no growth during methionine starvation. (B) Transcriptomic profile of top 50 upregulated genes in the Met4 activated strain show upregulation of methionine biosynthesis-related genes along with some important SCFMet30-related genes. There is no obvious functional enrichment within the Met4 upregulated genes that are not linked to methionine regulation.

Activation of Met4 and Met28 suggests that only Met4 is involved in methionine biosynthesis

Since we were unable to create null mutants of MET28, we could not test its involvement in methionine biosynthesis through loss of function, so we investigated both Met4 and Met28 function in methionine biosynthesis by adding the strong VP64 activation domain to each transcription factor (Ndisdang et al. 1998). The transcriptomic profile of cells containing Met4-VP64 showed up-regulation of SCFMet30, several methionine biosynthesis genes and some important Met30 related genes (Figure 2B). When we divide methionine biosynthesis into three different modules: module 1—the sulfur assimilation pathway; module 2—methionine biosynthesis (homoserine to methionine and cysteine), and module 3—the S-adenosylmethionine cycle; then the upregulated genes are in modules 1 and 3, with CYS3, CYS4, and MET2 of the methionine and cysteine biosynthesis and glutathione producing circuit not up-regulated. By contrast, Met28 activation shows a different set of upregulated genes, with none of them related to methionine biosynthesis. Among these genes 23/50 were annotated as biological function unknown, 7/50 are candidate secreted or cell wall-associated proteins, while 11/50 do not have convincing orthologs in other fungi. Furthermore, 10 out of 50 genes have the candidate 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ MetR DNA binding site in their promoter regions. Among these 10 genes, 2 are essential, and out of the top 40 up-regulated genes 9 genes are essential, which could explain the Met28 essentiality, but the upregulated genes do not allow a clear prediction of Met28 function (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Genes upregulated by Met28 activation. (A) Top 50 upregulated genes generated by activation of the CaMet28 transcription factor. There are 9 essential genes (in red color), 10 genes that have the AnMet28 DNA binding motif 5ʹTGRYRYCA 3ʹ, 23 genes that are annotated as biological function unknown, and 7 genes that encode candidate secreted or cell wall associated proteins (in blue color). (B) AnMet28 DNA binding motif 5ʹTGRYRYCA 3ʹ. (C) The location of the AnMet28 DNA binding motif in the upstream regions of specific upregulated genes.

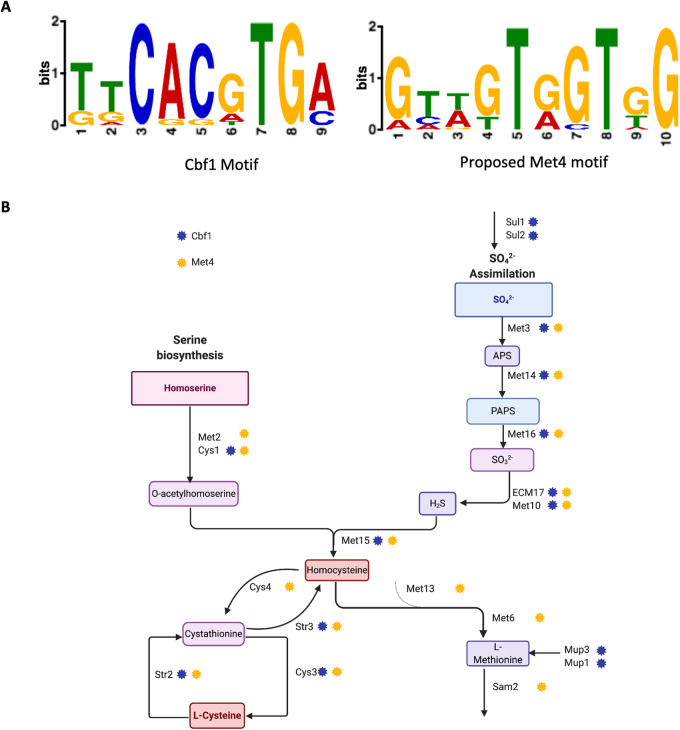

Potential Met4 binding sites in C. albicans

Alignment of the BZip domains shows the DNA binding region of CaMet4 is somewhat different from that of the CaMet28 and AnMetR/MetZ proteins, suggesting that it may bind a motif distinct from 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ (Figure 1). We used the MEME-suit software and checked the presence of potential motifs in the upstream region of the methionine genes in Candida. The two sequences identified with best E values were 5ʹ GTWGTRGTGG 3ʹ and the Cbf1 binding site TCACGTG. (Figure 4A). Because ChIP-chip analysis supports Cbf1’s involvement in methionine biosynthesis in C. albicans (Lavoie et al. 2010), it is possible that 5ʹ GTWGTRGTGG 3ʹ represents the binding target of CaMet4. Interestingly, across the different phylogenies studied, while the 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ motif is strongly associated with the Met regulon genes in the filamentous fungi, it becomes much less prevalent in the promoters of the Met regulon genes of L. elongosporus, and in species closely related to C. albicans or S. cerevisiae. In these species where the 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ motif is not strongly associated with the MET regulon, many of the MET regulon promoters have the 5ʹ GTWGTRGTGG 3ʹ motif identified in C. albicans as a candidate binding motif for Met4. This pattern is consistent with a transfer of the 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ/Met28 module away from the Met regulon, and the persistence of the Met4 connection with the Met regulon in C. albicans working through the 5ʹ GTWGTRGTGG 3ʹ motif (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 4.

Search for the Met4 Motif. (A) We used the Meme-suit online tool to look for potential regulatory binding sites. This approach identifies the Cbf1 motif in the upstream region of the upregulated methionine genes. The second-best motif we found is 5ʹCAACTCCAAR 3ʹ that may represent a Met4-binding motif. (B) A diagram highlighting the potential binding motifs of Cbf1 and Met4 throughout the methionine biosynthesis circuit.

Other transcription factors potentially involved in C. albicans methionine biosynthesis

While the regulation of methionine metabolism in Ascomycetes seems primarily controlled by the Met4 class of transcription factors, the regulation of the process in S. cerevisiae was found to be more complex. In particular, two transcription factor complexes have been identified to play a role, one centered on the DNA binding protein Cbf1, the other on the DNA binding paralogs Met31 and Met32. Each of these DNA binding elements associates with a pair of key cofactors, the bZIP proteins Met4 and Met28. In S. cerevisiae, the binding of Met4 and Met28 with Cbf1 involves the interaction of HLH domain of Cbf1 with the bZIP domains of Met28 and Met4 (Kuras et al. 1997).

Previous work had already linked the Cbf1 ortholog in C. albicans to methionine regulation (Lavoie et al. 2010) so we investigated whether orthologs of the Met31 and Met32 paralogs of S. cerevisiae are present in the genome of C. albicans. A single Met32 ortholog is conserved between S. cerevisiae and C. albicans but versions are not found in the filamentous fungi. Since the DNA-binding domain is completely conserved between the two fungi, it could be anticipated that CaMet32 would have same DNA-binding motif (5ʹ YYACTGTG 3ʹ) as seen for ScMet32. We used the MEME software to search for this 5ʹ YYACTGTG 3ʹ motif within the promoter sequences of the Candida genome. Approximately 400 genes had this motif upstream of their translation start sites; none of these, with the exception of Met4, were methionine biosynthesis genes. This observation suggests that the Met32 transcription factor may be rewired between C. albicans and S. cerevisiae. The two alleles of MET32 were deleted from the prototrophic strain SC5314. This MET32 deletion and did not cause any methionine auxotrophy (Figure 2A), but the deletion strain shows a moderately enhanced growth rate compared to the wild type in enriched media. This might be due to the fact that Met32 binding site was found in many genes of central metabolism like Ade2, Arg1, Dal2, Lys5, and Faa2.

Discussion

The metabolic pathways for the assimilation of sulfur and the biosynthesis of methionine are extensive, and play a key roles in the central metabolism of most cells (Thomas et al. 1995; Marzluf 1997; Thomas and Surdin-Kerjan 1997; Mendoza-Cozatl et al. 2005; Hebert et al. 2011; Petti et al. 2012). Within the ascomycete fungi, the regulation of the circuitry ranges from relatively simple in filamentous fungi, to quite complex in the baker’s yeast. In filamentous fungi, it involves a single (or sometimes duplicated) bZIP transcription factor (Marzluf and Metzenberg 1968). However, in the model yeast S. cerevisiae, regulation involves two protein complexes made up of distinct DNA binding components and a set of associating factors (Bram and Kornberg 1987; Baker et al. 1989; Baker and Masison 1990; Rouillon et al. 2000; Kaiser et al. 2006). Here we have investigated the regulatory circuitry in the opportunistic fungal pathogen C. albicans. Consistent with its phylogenetic position between the filamentous fungi and the bakers’ yeast, regulation of methionine biosynthesis in C. albicans appears intermediate; more complex than that in the filamentous fungi, but not as complex as that in S. cerevisiae.

C. albicans contains two key transcription factors controlling methionine biogenesis, the bHLH factor Cbf1 and the bZIP factor Met4. We had shown that methionine genes including Met4 have a Cbf1 DNA-binding motif in their promoters, and confirmed binding to these and other promoters by ChIP-CHIP analysis (Lavoie et al. 2010). Some key genes like MET2, SAH1, CYS4 MET13, MET6, and SAM2 lack Cbf1-binding sites, while the transporter proteins for sulfate (Sul1/2) and methionine (Mup1/3) are under the sole control of Cbf1. Mup1 has an essential role in methionine-induced morphogenesis, biofilm formation and survival inside the macrophages and virulence (Schrevens et al. 2018). We established that deletion of Met4 causes methionine auxotrophy, which suggests that, as found with other fungi, C. albicans methionine biosynthesis is dependent on a Met4 ortholog. In addition to their general requirement in normal metabolism, methionine genes are upregulated in biofilms (García-Sánchez et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2013; Uppuluri et al. 2018), as well as in planktonic cells derived from biofilms (Uppuluri et al. 2018). Neither Cbf1 nor Met4 are transcriptionally upregulated during biofilm formation, although the majority of the biofilm up-regulated methionine pathway genes are regulated by either Met4 alone or both Met4 and Cbf1.

CaMet4 shows convincing molecular evidence as a regulator of methionine circuitry, as activation of the protein through the creation of a Met4-VP64 fusion upregulated many methionine biosynthesis genes, although cysteine biosynthesis (CYS3 and CYS4), and glutathione-associated genes were not affected. We also observed enhanced expression of serine and glycine-related genes that directly or indirectly are involved in methionine and glutathione production (Wen et al. 2004). We looked for potential DNA-binding motifs in the promoters of the methionine regulon and found 5ʹ GTWGTRGTGG 3ʹ and 5′-TCACGTG-3′. Because 5ʹ CACGTG 3ʹ represents the Cbf1-binding target (Lavoie et al. 2010), it is possible that this 5ʹ GTWGTRGTGG 3ʹ motif represents the Met4 target. This motif is quite different from the 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ motif that represents the binding motif of the Met4 orthologs in the filamentous fungi; it appears that the 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ motif is disconnected from the C. albicans MET regulon, while Met4 remains associated with the C. albicans MET regulon but uses the 5ʹ GTWGTRGTGG 3ʹ motif as a binding site.

A paralog of CaMet4, Orf19.7046, has been annotated in C. albicans as Met28; this protein shows highest sequence similarity to AnMetR and NcZip1 (Figure 1), while its similarity to Met28 of S. cerevisiae is limited to its bZIP domain and its very similar size. The MET28 gene appears essential in Candida, and transcription profiling of cells with the activating Met28-VP64 fusion suggests that this TF is not involved in methionine biosynthesis (Figure 3). Among the upregulated genes were several essential genes, and searching the promoters of the upregulated set identified a candidate binding sequence similar to the motif 5ʹ AGRYRYCAT 3ʹ recognized by AnMetR. Because the AnMet4 and CaMet28 proteins potentially share this DNA-binding motif, the genes upregulated by the Met28-VP64 fusion and containing this promoter motif may represent a Met28 controlled regulon. This suggests that the 5ʹ AGRYRYCAT 3ʹ motif remains connected to a Met4-type protein, in this case, the paralog Met28, but the motif has been disconnected from the MET regulon. No clear cellular process is evident among these upregulated genes, but because a large fraction of them have currently undefined functions in C. albicans, it is possible further work may uncover some functional relationships. While the activation of the Met28 does not create any obvious morphological or growth phenotype, it is interesting to note that expression of MET28 is highly upregulated during host infection (Xu et al. 2015). A repositioning of the Met4 ortholog of S. pombe, SpZip1, away from control of the methionine regulon has also been observed (Harrison et al. 2005), showing that Met4 orthologs are not uniquely associated with methionine pathway regulation.

We were interested in the potential trajectory of the evolution of the methionine regulatory circuitry from the simple pattern in the filamentous fungi to the more complex arrangement in S. cerevisiae. One key step that occurred during this transition is the recruitment of the Cbf1 factor into methionine regulation. The orthologs of Cbf1 in the filamentous fungi like Eurotials, Onygenales, and Taphrinomycotina clades do not appear involved in methionine biosynthesis, as connection of the Cbf1 binding motif is found in the promoters of the methionine regulon only in the Candida, Protoploid (K. lactis), and Saccharomyces clades (Figure 4). In the Candida clade, there are therefore two transcription factors (Cbf1 and Met4) co-ordinating the expression of the methionine regulon, but there is no evidence for a direct physical interaction between these two factors. However, they may frequently be found in close proximity on the DNA molecule, as the potential binding sites for the Cbf1 and Met4 proteins in the promoters are often closely adjacent.

The transition from the C. albicans framework to that seen in S. cerevisiae involves other steps. One is the recruitment of the Met31/32 protein to methionine regulation. In S. cerevisiae, Met31 and its paralog Met32 are both involved in methionine biosynthesis, although not uniquely, as 455 genes are primarily dependent on Met32 (Petti et al. 2012). In Candida, deletion of Met32 does not confer methionine auxotrophy, and although we found almost 400 genes (at a 5% false discovery rate) with the candidate Met32 binding sequence (5ʹ YYACTGTG 3ʹ) in their promoter, only MET4 of the sulfur or methionine related genes had this motif. A. nidulans also has this sequence in the promoters of many genes, but not methionine genes, suggesting that throughout the ascomycetes Met32 functions as a general TF. In K. lactis, a few methionine genes like MET2 and MET6 have the Met32 motif in their promoters, while after the whole genome duplication the 5ʹ YYACTGTG 3ʹ sequence becomes extensively linked to methionine biosynthesis.

An additional step in the formation of the S. cerevisiae regulatory circuitry is the transition of Met4 from a DNA-binding transcription factor to an activation-domain-containing cofactor that uses Cbf1 and Met31/32 as targeting components. This transition may have been precipitated by the appearance of new sequence in the protein that both disrupted the bZIP DNA binding region of ScMet4 (Hebert et al. 2011) (Figure 1), and established protein–protein interactions with Cbf1 and Met31/32. Such a transition could be facilitated by the proximity of Cbf1 and Met4 binding sites on DNA; a weakening of Met4 DNA binding could be compensated by a protein-protein association, thus keeping the functional relationship intact (Met4 and Cbf1 associating with the methionine regulon promoters) but modifying the details of the association (independent DNA binding switching to protein association and use of only one element for DNA binding). bZIP factors are known for their extensive and drastic changes in rewiring and interactions. Previous research suggested that protein–protein interactions (dimer formation) are often associated with DNA binding activity, so modifications in one process frequently affects the other (Reinke et al. 2013). ScMet4 lost dimer-formation interactions resulting in partial DNA–protein interactions. The combination of BHLH and BZip factors is very common in higher eukaryotes; for example, in mammals the transactivation factors Myc (BHLH) and Max (bZIP) show interactions just like the Met4–CBF complex (Vancraenenbroeck and Hofmann 2018).

There thus appears to be a gradual transition from single protein regulation to a complex circuit in methionine biosynthesis in the ascomycete fungi (Figure 5). In filamentous ascomycetes, there are no clear orthologs of Cbf1, Met32-like proteins are functioning as general transcription factors, and the methionine circuitry is uniquely controlled by Met4 orthologs. In the Candida clade, Met32 is still acting as a general factor, while Met4 and Cbf1 orthologs have been recruited to methionine regulation. In K. lactis, more Met-related genes have been incorporated into the Met32 control circuit, and this connection is made stronger after the WGD. Finally, in the S. cerevisiae lineage, Met4 and another B-zip factor Met28 apparently transition from autonomously acting factors to become transactivating cofactors through a reduction in DNA binding, and an enhancement in protein–protein associations with the DNA-binding elements Cbf1 and Met31/32. It is interesting that throughout these changes the control modules tend to be dual (MetR/MetZ in A. nidulans; Met4/Cbf1 in C. albicans; Met31/32 and Cbf1 complexes in S. cerevisiae), suggesting the complexity of methionine regulation may be best served by more than a simple single transcription regulator.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of methionine regulatory transcriptional factors across the ascomycetes. In the phylogenetic tree, a Met4 ortholog is involved with the methionine biosynthesis in most of the fungi. Cbf1 was rewired and connects to methionine regulation in the CTG clade, whereas Met32 and Met28 are connected to the pathway later in the protoploids. The designation “I” for involved in methionine biosynthesis, “NI” for not involved, and “-” for not present in the genome, represent the situation for all species in the group identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of M.W lab for valuable comments during this study. We want to acknowledge support from the NSERC, NSFC, and Concordia University. We also thank Dr. David Walsh for his advice and guidance throughout the project.

Funding

We acknowledge funding support from the NSERC Discovery RGPIN/4799 (M.W.), NSFC grant No. 82072261(J.F.) and NSERC Canada Research Chair 950-228957 (M.W.).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Literature cited

- Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. 2015. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:W39–W49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RE, Fitzgerald-Hayes M, O'Brien TC. 1989. Purification of the yeast centromere binding protein CP1 and a mutational analysis of its binding site. J Biol Chem. 264:10843–10850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RE, Masison DC. 1990. Isolation of the gene encoding the Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromere-binding protein CP1. Mol Cell Biol. 10:2458–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey R, Baudouin-Cornu P, Lee TA, Rouillon A, Zarzov P, et al. 2005. Inducible dissociation of SCF(Met30) ubiquitin ligase mediates a rapid transcriptional response to cadmium. EMBO J. 24:521–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaiseau PL, Thomas D. 1998. Multiple transcriptional activation complexes tether the yeast activator Met4 to DNA. EMBO J. 17:6327–6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bram RJ, Kornberg RD. 1987. Isolation of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromere DNA-binding protein, its human homolog, and its possible role as a transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 7:403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. 2002. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez S, Aubert S, Iraqui IL, Janbon G, Ghigo J-M, et al. 2004. Candida albicans biofilms: a developmental state associated with specific and stable gene expression patterns. Eukaryotic Cell. 3:536–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison C, Katayama S, Dhut S, Chen D, Jones N, et al. 2005. SCF(Pof1)-ubiquitin and its target Zip1 transcription factor mediate cadmium response in fission yeast. EMBO J. 24:599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert A, Casaregola S, Beckerich JM. 2011. Biodiversity in sulfur metabolism in hemiascomycetous yeasts. FEMS Yeast Res. 11:366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P, Su NY, Yen JL, Ouni I, Flick K. 2006. The yeast ubiquitin ligase SCFMet30: connecting environmental and intracellular conditions to cell division. Cell Div. 1:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L, Barbey R, Thomas D. 1997. Assembly of a bZIP-bHLH transcription activation complex: formation of the yeast Cbf1-Met4-Met28 complex is regulated through Met28 stimulation of Cbf1 DNA binding. EMBO J. 16:2441–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L, Rouillon A, Lee T, Barbey R, Tyers M, et al. 2002. Dual regulation of the met4 transcription factor by ubiquitin-dependent degradation and inhibition of promoter recruitment. Mol Cell. 10:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie H, Hogues H, Mallick J, Sellam A, Nantel A, et al. 2010. Evolutionary tinkering with conserved components of a transcriptional regulatory network. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TA, Jorgensen P, Bognar AL, Peyraud C, Thomas D, et al. 2010. Dissection of combinatorial control by the Met4 transcriptional complex. Mol Biol Cell. 21:456–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Marzluf GA. 1996. Determination of the Neurospora crassa CYS 3 sulfur regulatory protein consensus DNA-binding site: amino-acid substitutions in the CYS3 bZIP domain that alter DNA-binding specificity. Curr Genet. 30:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Marzluf GA. 1997. Molecular genetics of sulfur assimilation in filamentous fungi and yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 51:73–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzluf GA, Metzenberg RL. 1968. Positive control by the cys-3 locus in regulation of sulfur metabolism in Neurospora. J Mol Biol. 33:423–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cozatl D, Loza-Tavera H, Hernandez-Navarro A, Moreno-Sanchez R. 2005. Sulfur assimilation and glutathione metabolism under cadmium stress in yeast, protists and plants. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 29:653–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndisdang D, Morris PJ, Chapman C, Ho L, Singer A, et al. 1998. The HPV-activating cellular transcription factor Brn-3a is overexpressed in CIN3 cervical lesions. J Clin Invest. 101:1687–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, et al. 2015. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 33:290–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti AA, McIsaac RS, Ho-Shing O, Bussemaker HJ, Botstein D. 2012. Combinatorial control of diverse metabolic and physiological functions by transcriptional regulators of the yeast sulfur assimilation pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 23:3008–3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piłsyk S, Natorff R, Sieńko M, Skoneczny M, Paszewski A, et al. 2015. The Aspergillus nidulans metZ gene encodes a transcription factor involved in regulation of sulfur metabolism in this fungus and other Eurotiales. Curr Genet. 61:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke AW, Baek J, Ashenberg O, Keating AE. 2013. Networks of bZIP protein-protein interactions diversified over a billion years of evolution. Science. 340:730–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillon A, Barbey R, Patton EE, Tyers M, Thomas D. 2000. Feedback-regulated degradation of the transcriptional activator Met4 is triggered by the SCF(Met30) complex. EMBO J. 19:282–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrevens S, Van Zeebroeck G, Riedelberger M, Tournu H, Kuchler K, et al. 2018. Methionine is required for cAMP-PKA mediated morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans (vol 108, pg 258, 2018). Mol Microbiol. 109:415–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ES, Gritsenko V, Levitan A, Yadav B, Dror N, et al. 2018. Gene essentiality analyzed by in vivo transposon mutagenesis and machine learning in a stable haploid isolate of Candida albicans. mBio. 9: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggers T, Duyzend MH, Reddy J, Khan S, Bulyk ML. 2011. Non-DNA-binding cofactors enhance DNA-binding specificity of a transcriptional regulatory complex. Mol Syst Biol. 7:555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Kuras L, Barbey R, Cherest H, Blaiseau PL, et al. 1995. Met30p, a yeast transcriptional inhibitor that responds to S-adenosylmethionine, is an essential protein with WD40 repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 15:6526–6534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Surdin-Kerjan Y. 1997. Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 61:503–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppuluri P, Zaldivar MA, Anderson MZ, Dunn MJ, Berman J, et al. 2018. Candida albicans dispersed cells are developmentally distinct from biofilm and planktonic cells. Mbio. 9:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancraenenbroeck R, Hofmann H. 2018. Occupancies in the DNA-binding pathways of intrinsically disordered helix-loop-helix leucine-zipper proteins. J Phys Chem B. 122:11460–11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas VK, Barrasa MI, Fink GR. 2015. A Candida albicans CRISPR system permits genetic engineering of essential genes and gene families. Sci Adv. 1:e1500248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wapinski I, Pfeffer A, Friedman N, Regev A. 2007. Automatic genome-wide reconstruction of phylogenetic gene trees. Bioinformatics. 23:i549–i558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen S, Zhang T, Tan T. 2004. Utilization of amino acids to enhance glutathione production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb Technol. 35:501–507. [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Solis NV, Ehrlich RL, Woolford CA, Filler SG, et al. 2015. Activation and alliance of regulatory pathways in C. albicans during mammalian infection. PLoS Biol. 13:e1002076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu ZY, Wang H, Shang QH, Jiang YY, Cao YY, et al. 2013. Time course analysis of Candida albicans metabolites during biofilm development. J Proteome Res. 12:2375–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. Strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Plasmids and primers used with their respective sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Supplementary Figure S1 which consist of the promoters of methionine genes across the fungal phylogeny of the candidate Met4 motif 5ʹ ATGRYRYCAT 3ʹ and the new potential Met4 recognition motif of the CUG clade 5ʹ CAACTCCAAR 3ʹ. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data are accessible through GEO Series accession number: GSE162171. Supplemental material available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13326395.