Abstract

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) probes using thin-film high temperature superconducting (HTS) resonators offer high sensitivity and are particularly suitable for small-sample applications. We are developing an improved 1.5 mm HTS NMR probe designed for operation at 14.1 T and optimized for 13C detection. The total sample volume is about 35 μL and the active sample volume is 20 μL. The probe employs HTS resonators for 13C and 1H transmission and detection and the 2H lock. We examine the interactions of multiple superconducting resonators and normal metal tuning loops on coil resonance frequency and probe sensitivity. We test a recently introduced 13C resonator design, engineered to significantly increase 13C detection sensitivity over previous all-HTS probes. At zero field, we observe a 13C quality factor of 6000 which is several times higher than previous resonators. In this work the coil design considerations and probe build-out procedure are discussed.

Keywords: Nuclear magnetic resonance, high-temperature superconductors, superconducting devices

I. Introduction

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a powerful molecular characterization technique useful for the study of solution samples in biology, biochemistry, and organic chemistry. 13C detection provides direct information concerning the carbon scaffolding that forms biological molecules and is ideal for natural products chemistry and metabolomics applications. However, 13C NMR suffers from low sensitivity because of its 1.1% natural abundance and low gyromagnetic ratio [1]. Enhancing the sensitivity on an NMR probe can be effectively accomplished by improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the NMR probe. The SNR of a probe for a given sample can be described by

| (1) |

where M0 is the sample magnetization, B1/I is the strength of the RF excitation pulse per unit current in the coil, Tcoil, Ta, and Ts are the coil, preamplifier and sample noise temperatures, respectively, and Rs and Rcoil are the effective resistance of the sample and coil, respectively [2]. Thin-film high temperature superconducting (HTS) resonators improve SNR by reducing coil resistance Rcoil beyond what can be achieved with a normal metal coil [3]–[6]. We report here the design, construction, and rf measurements of an improved 1.5 mm 13C-optimized all-HTS NMR probe. A 1.5 mm 13C-optimized all-HTS probe [1] of similar design (including a 15N channel) previously developed in our lab has shown to be a powerful tool for metabolomics applications [7]–[11]. Although the previous probe achieved the highest 13C mass sensitivity of any solution NMR probe when it was introduced, it did not realize the full potential of using HTS coils (mass sensitivity in NMR is defined as the SNR of a standard measurement divided by the volume of sample used for the measurement). Advances in probe construction technique and coil design are expected to produce significant improvements in 13C detection sensitivity over the previous probe. Also, by employing an effective model of inter-probe resonator interactions to inform resonance frequency adjustments, the efficiency of the probe build-out process was improved [12].

II. Probe Design

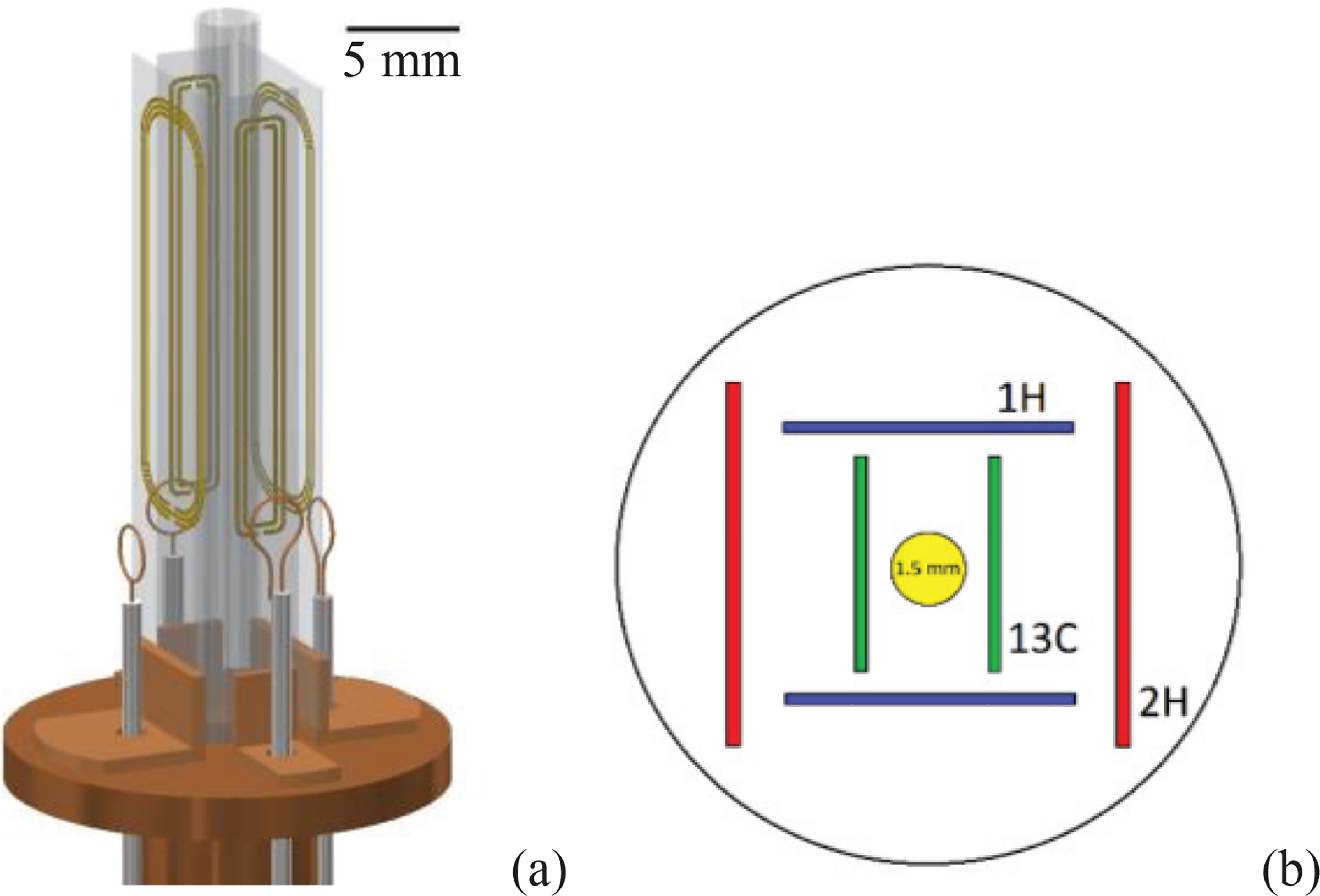

The 13C optimized 1.5 mm all-HTS probe in development was designed for a nominally 600 MHz NMR spectrometer. The total sample fill volume is about 35 μl and active sample volume is 20 μl. The probe features 13C and 1H detection channels and a 2H lock system which ensures the spectrometer operates at a constant net magnetic field [13]. At the magnet’s field of 14.1 T, isotopes 13C, 1H, and 2H have Larmor frequencies of 150.8 MHz, 599.7 MHz, and 92.1 MHz, respectively. The cryogenic probe body features three pairs of HTS coils mounted in a Helmholtz-like configuration with coupled resonances at the Larmor frequencies of 13C, 1H and 2H (Fig. 1). Each of the six individual coils was patterned by Star Cryoelectronics (Santa Fe, NM, USA) from ~300 nm-thick films of Y1Ba2Cu3O7-δ (YBCO) coated epitaxially onto 430 μm-thick sapphire substrates by Ceraco, GmBH (Ismaning, Germany). The probe-head was maintained at vacuum and cooled using a Varian cryogenic system to 35 K, well under the superconducting transition temperature of YBCO (93 K). To inductively couple energy into the coil pairs, three movable coaxial cables terminated into normal-metal loops were adjusted to minimize the reflection coefficient S11 at the relevant modes. A vector network analyzer (VNA) was used to measure the reflected response in continuous wave (CW) mode at 0 dBm incident power, which is below the non-linearity threshold of the HTS coils [14]. Three shorted inductive normal-metal tuning loops were employed to give users the ability to finely tune probe resonances to the exact Larmor frequencies of the nuclei intended for detection during routine probe use [1, 3, 15, 16].

Fig. 1.

Design of the 1.5-mm all-HTS NMR probe. Some details and dimensions are simplified or distorted for illustrative purposes and are not exact reproductions of the design. (a) Diagram of the NMR probe-head illustrating the arrangement of two pairs of HTS coils and the corresponding normal metal power-matching and tuning loops. (b) Cross-sectional schematic of the coil arrangement. Three Helmholtz-like pairs are maintained under vacuum at 35 K and surround the 1.5-mm sample tube.

A. Coil Designs

To maximize sensitivity, the 13C detection coils were placed closest to the sample. Counter-wound spiral resonator designs were employed for the 13C resonators (Fig. 2a). This design is useful for the innermost coils because the large stray electric field usually associated with low frequency spiral coils is trapped within the sapphire between two spirals [1, 17]. The first iteration of the probe employed two single-sided spiral resonators glued back-to-back [17]. Such a configuration reduced the filling factor of the probe due to the doubled substrate thickness. The current 13C coil design utilizes double-side coated wafers to improve filling factor [18]. Two 4-turn spiral YBCO structures with opposite handedness were coated onto either side of the sapphire substrate.

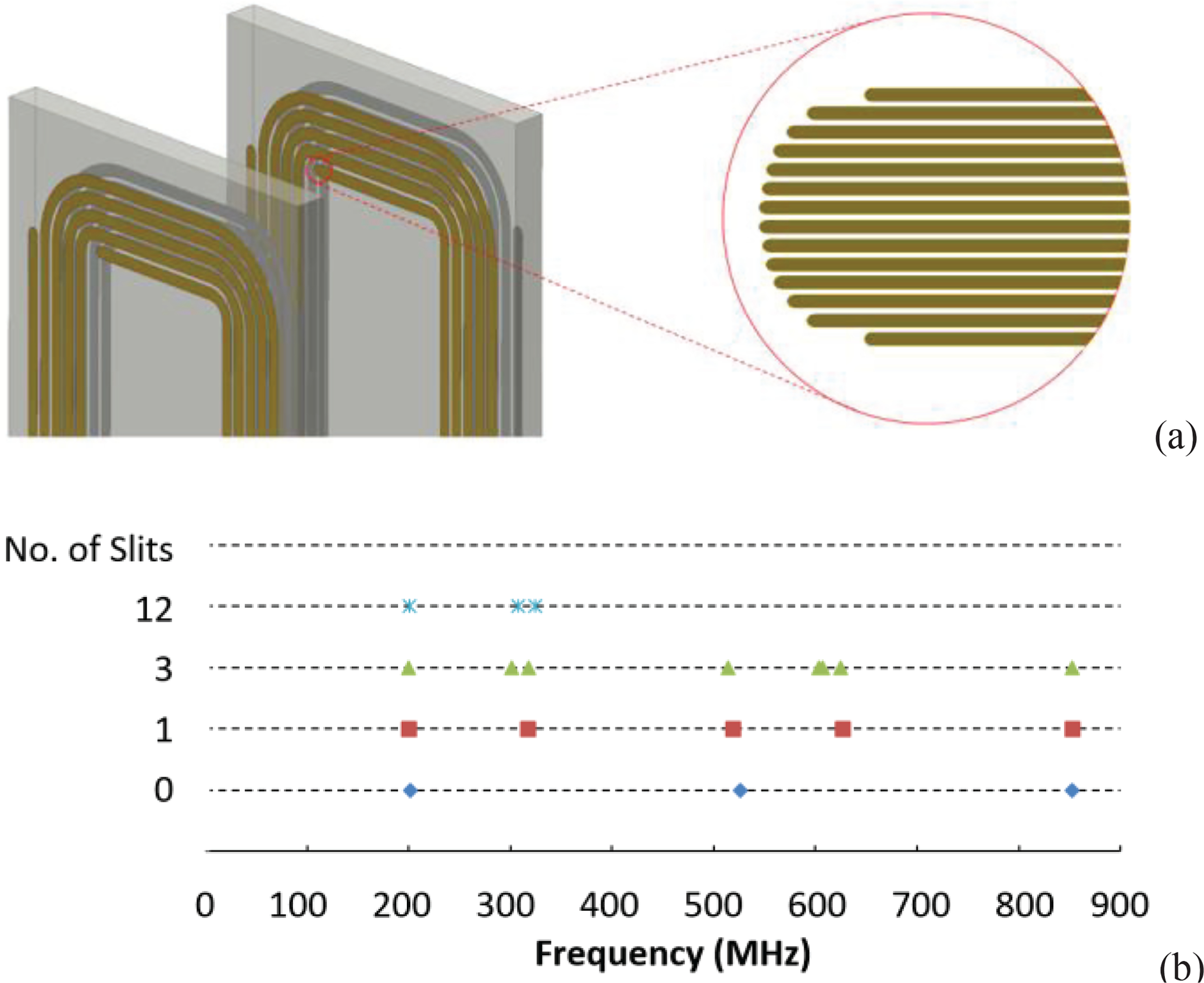

Fig. 2.

Design of the 13C detection coils. (a) Pair of counter-wound spiral resonators. Each resonator employs two 4-turn YBCO spiral structures with opposite handedness coated onto either side of a sapphire substrate. To reduce magnetization, the HTS resonators are slit into 14 fine parallel fingerlets. The slits cause each mode to split into a family of modelets. (b) The modelets of one single-sided spiral coil as simulated using IE3D.

To minimize the effect of the diamagnetism of the superconductor on the static magnetic field and improve lineshape, the 144.5 μm spiral traces of the 13C spiral resonators were slit into 14 fine parallel “fingerlets”, each 8 μm wide and separated by 2.5 μm (Fig. 2a). This minorly affected the rf performance of the coil but is expected to reduce magnetization effects by a factor of approximately 14 [19]. This also allowed the current in adjacent fingerlets to flow in opposite directions, causing each spiral mode to split into a family of modelets. Many of these spurious modes were too close to the 1H Larmor frequency (600 MHz in our case) and would interfere with 1H detection. In the previous design, a gold overlayer was employed to suppress the modelets [20]. While this normal-metal overlayer was successful in suppressing the modelets, it also significantly increased the loss of the resonator. Thus, the sensitivity of the 13C channel was reduced. Removing this gold layer was our main design goal for the new 13C detection coils.

The EM simulation program IE3D (Mentor Graphics) was used to assist in the design of the 13C resonator. By simulating the resonance spectra of candidate spiral coil designs in IE3D, we determined that the splitting of modelets follows a consistent pattern (Fig. 2b). When the coil is slit into 2 fingerlets, each mode of the spiral splits into 2 modelets. It can be noted that the lower modelet has currents flowing in the same direction in the two fingerlets, whereas in the upper modelet, the currents in the two fingerlets are flowing in opposite directions. Further slitting of the spiral produces more modelets just below the upper modelet of the 1-slit coil. Thus, a relatively simple simulation of the 1-slit counter-wound spiral can be used to know the approximate range of frequencies for the modelets.

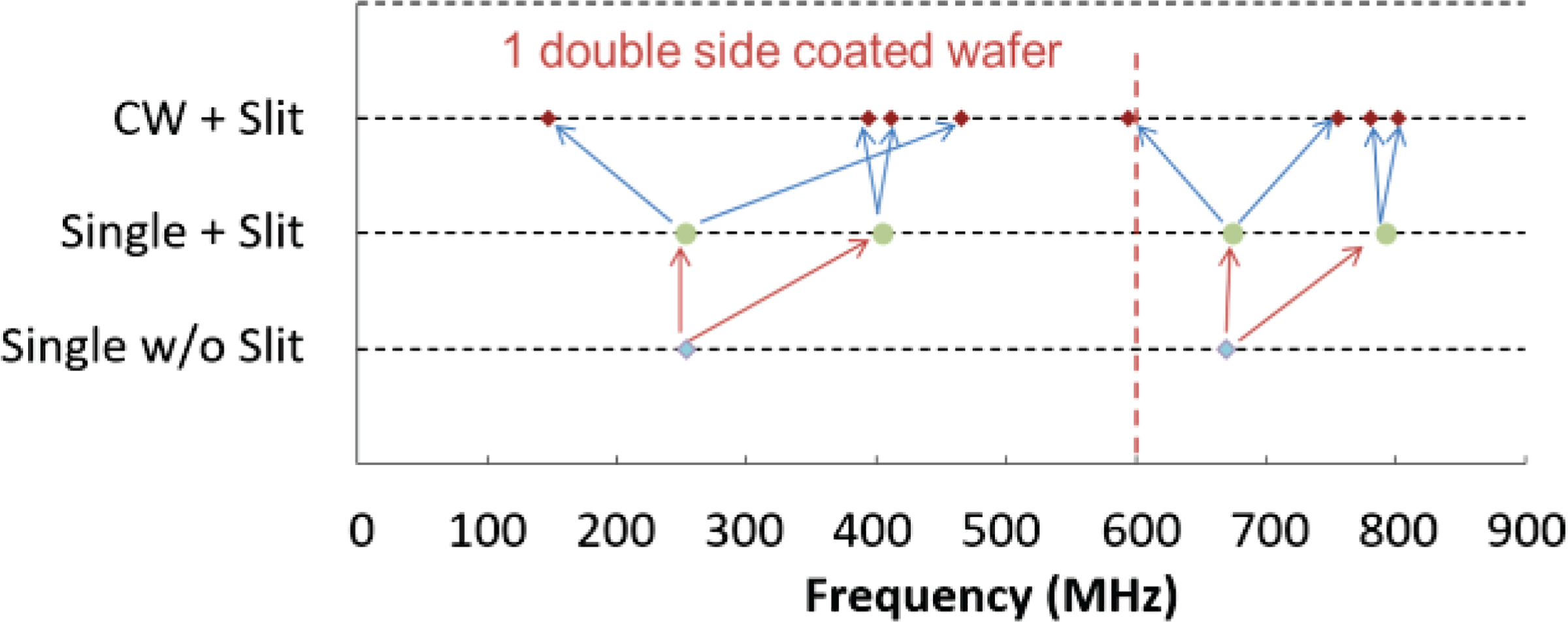

Fig. 3 shows the predicted modes of our current counter-wound spiral coil. All the modelets of a single spiral show a further splitting when they are used in a counter-wound configuration. As can be seen, we expect to have a family of modelets originating from the fundamental mode of the spiral to resonate well below the 1H Larmor frequency. Our simulation shows only a single mode near the 1H resonance. The higher modes of the spiral have very little dipole moment and do not shift appreciably when two counter-wound spiral coils are deployed in a Helmholtz configuration. We expect that this resonance can be easily shifted away during the laser trimming process to adjust the coil frequency. Thus, it was safe to omit the gold overlayer. By contrast, the older version of the coil, if the gold overlayer was omitted would have produced a family of modelets around the 1H Larmor frequency which cannot be easily shifted away with laser trimming.

Fig. 3.

Simulated modes of our current counter-wound (CW) spiral 13C detection coils. The modelets of the slit single spiral coil show further splitting when they are used in a CW spiral arrangement. Our simulation shows only a single mode near the 1H resonance of 600 MHz.

The 1H and 2H coils employed the same design as in the previous probe of similar design described in [1]. In short, a single-sided interdigital-capacitor based design, known as a racetrack design, with 24 fingers and four gaps was used for the 1H detection coils [21]. The 2H detection coils employed a single-sided spiral resonant structure with 10 turns.

B. Coil Resonance Adjustments

In constructing this probe, we also looked to develop methods to increase the general efficiency of the build-out process of HTS probes. HTS probe construction can be a tedious and time-consuming process, which is part of the reason that HTS coils have yet to be widely implemented in commercial NMR probes. The sensitivity of HTS coils to their local environment is a significant contributor to this difficulty. In multi-channel HTS probes, the coils are packed tightly around the sample and each coil’s resonance frequency is appreciably shifted by the presence of the other HTS resonators. The resulting resonances are the coupled resonances of all the resonators, not just the Helmholtz pairs. Additionally, variability in substrate thickness and coil patterning lead to differences in resonance frequency between coils of the same design. Therefore, coil resonance frequencies must be adjusted after fabrication. However, without a model describing coil interactions and resonance shifts the necessary adjustments to each coil are unknown. A build-out procedure generally requires four or more iterative adjustments to each coil to get within the tuning range of the tuning loops, about 1 to 2 percent of the coil resonance frequency.

The magnetic coupling model described in detail in [12] was used to predict the individual coil resonances required for the ensemble of HTS coils to obtain the desired set of coupled modes. We hoped that by modeling only the magnetic coupling we could describe coil interactions with sufficient accuracy to reduce coil adjustment procedures to one to two steps. To adjust the resonance of a coil a 532-nm laser mounted on a microscope probe station was used to eliminate portions of YBCO and increase the resonance of each coil to the desired frequency [22]. To predict what the resonance frequency of a single coil would be after a laser trim, we conducted trimming simulations using the EM simulation tool Sonnet™ (Sonnet Software, Inc., Syracuse, NY).

An additional problem for laser trimming the new double-sided resonators is the difficulty of trimming one side of the resonator without damaging the opposite side. To address this problem, each side of the 13C resonator was designed with a non-overlapping half turn. We determined that with a sufficiently small laser beam size one side of the coil could be trimmed without affecting the opposite side.

III. Results and Discussion

Much of the influence of a resonator on probe sensitivity can be quantified by the measurement of its quality factor (Q factor or Q), where . With the final coil adjustments made and the coupling and tuning loops relatively optimized, the new probe Q factors can now be compared with zero field data from the previous 1.5 mm 13C-optimized all-HTS probe of similar design. The matched Q factors measured from the −3 dB points of the reflection coefficients of the fully loaded and tuned probe in no external magnetic field are listed in the table below:

| Nucleus | FLarmor (MHz) | QLarmor |

|---|---|---|

| 13C | 150.81 | 6000 |

| 1H | 599.69 | 3900 |

| 2H | 92.06 | 2100 |

These Q factors compare very favorably to the zero field Q factors of 1900, 2000, and 1500 for 13C, 1H, and 2H channels, respectively, observed in the previous probe. Notably, the new 13C coil design exhibits 3.2 times the Q factor. In recent in-field tests, 13C channel Q is largely preserved since the coil substrate-planes are mounted approximately parallel to the applied magnetic field [23]. We measure a 13C channel Q factor of 5500 at 14.1 T, compared a Q factor of 1700 in the previous probe. The effects of the normal metal tuning loops on the nearby HTS resonators can be significant and small adjustments in loop position can cause large changes in probe sensitivity. Still more sensitivity can be gained by moving the tuning loop slightly away from the 13C coils to decrease eddy currents. In zero field tests we have observed a Q of 14000 at the low end of the tuning range where the normal-metal tuning loop minimally couples to the 13C resonators. However, there are questions as to whether we have the sufficient stability to support such a high Q in this probe body, and more generally if such a high Q is even useful given the ~200 ppm chemical shift dispersion range of 13C. We may choose to make these sensitivity improvements iteratively rather than all at once.

Since the gold overlayer used in previous 13C detection coil designs was omitted in our design, we expected to observe a single mode near the 1H resonance of 600 MHz. Experimental results agreed with the IE3D simulations shown in figure 3. In single coil tests a single mode was observed at 576 MHz with no nearby modelets. Thus, the new 13C coils facilitate a large increase in 13C detection sensitivity and do not interfere with hydrogen detection.

Probe sensitivity was improved across all channels even though only 13C detection coils received a design upgrade. In part, this may be due to the extensive optimizations we made to the size, shape, and position of the inductive tuning loops. We used particularly large 2H tuning loops located far away from the 2H resonators to decrease eddy current losses and increased the 2H channel Q. However, this may not account for the entire 95% and 40% increases in Q observed on the 1H and 2H channels when compared to the previous probe. Additional improvements may be attributed to the lack of a 15N channel in new probe. We established by measuring coupling constants between resonator pairs that pairs that are orthogonal and close in proximity can couple as strongly as Helmholtz pairs [12]. The HTS 15N detection coils in the old probe were nested exterior to the other three coil pairs and parallel to the 1H coils [1]. Since the old probe had the same dimensions as the current probe, the 15N resonators were close in proximity to the 1H and 2H resonators. While the 15N coils were HTS, we can still expect some Q loss. Of more significance was the position of the 1H normal metal-tuning loop, which needed to be placed in the small gap between the 15N and 1H resonators. It was not imperative to place the normal-metal loop so near to the 1H coils in the new probe. Finally, we may also be observing improvements in HTS film quality on all coils.

The magnetic coupling model was successful in accurately predicting the coupled modes of the probe. Using the measured single coil resonances, the magnetic coupling model allowed us to predict the coupled resonances with a RMSPE of 0.82 [12]. The coupling constants did not change after coil trims. Additionally, implementing accurate trimming simulations using the EM simulation tool Sonnet™ enabled the prediction of single coil resonance adjustments via laser trimming with an average error of 0.27%. We calculate that a trimming method which only considered Helmholtz pair resonances would have at best made predictions of the 13C coupled resonance with ~2.5% error without considering the effects of other coils. This error is larger than the fine-tuning range of the inductive tuning loops. Furthermore, a “coil spreader” was fitted atop the coil assembly during fully loaded probe measurements. This forced the six coils into a consistent yet unique set of positions when measuring the coupled modes of the full probe. These unique positions were not replicable during experiments where only two coils were measured. Therefore, a coupling model describing the interactions of all six coils is essential in completing trimming within one or two steps.

IV. Conclusion

The new 1.5 mm 13C-optimized all-HTS NMR probe described here exhibits a significantly better 13C Q factor which should provide a significant increase in 13C detection sensitivity. Probe sensitivity was also improved on the 1H detection channel and the 2H lock channel. We also demonstrated the substantial effect of normal metal inductive tuning loops on coil Q factors and the importance of accuracy when predicting coupled probe resonances. The application of a magnetic coupling model in conjunction with trimming simulations improved the efficacy of the coil trimming process. The probe has been recently installed in the 600 MHz spectrometer at the University of Florida (UF) and preliminary tests are underway. The remaining in-field tests will be performed at the UF to demonstrate the utility of this probe for 13C-based metabolomics.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Steve Ranner and Jason Kitchen for valuable technical support and Dr. Jerris Hooker for assistance with coil simulations.

This work was supported by NIH/NIGMS grant P41 GM122698. A portion of the work was done at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory which is supported by the NSF through Cooperative Agreement DMR-1644779 and by the State of Florida.

Contributor Information

Jeremy N. Thomas, National High Magnetic Laboratory and the Department of Physics, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32310 USA.

Vijaykumar Ramaswamy, Bruker Biospin AG, Faellanden 8117, Switzerland.

Ilya M. Litvak, National High Magnetic Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32310 USA

Taylor L. Johnston, National High Magnetic Laboratory and the Department of Chemistry, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32310 USA

Arthur S. Edison, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 USA

William W. Brey, National High Magnetic Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32310 USA

References

- [1].Ramaswamy V, Hooker JW, Withers RS, Nast RE, Brey WW, and Edison AS, “Development of a C-13-optimized 1.5-mm high temperature superconducting NMR probe,” J. Magn. Reson, vol. 235, pp. 58–65, October. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kovacs H, Moskau D, and Spraul M, “Cryogenically cooled probes--a leap in NMR technology,” Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc, vol. 46, no. 2–3, pp. 131–155, May 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2005.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yamada T et al. , “Electromagnetic Evaluation of HTS RF Coils for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 1–4, June. 2015, doi: 10.1109/TASC.2014.2368778.32863691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Anderson WA et al. , “High-sensitivity NMR spectroscopy probe using superconductive coils,” Bull. Magn. Reson, vol. 17, no. 1–4, pp. 98–102, July. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Oikawa S et al. , “Evaluation of superconducting pickup coils with high Q for 700 MHz NMR,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser, vol. 507, no. 4, p. 042028, May 2014, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/507/4/042028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hill HDW, “Improved sensitivity of NMR spectroscopy probes by use of high-temperature superconductive detection coils,” Ieee Trans. Appl. Supercond, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 3750–3755, June. 1997, doi: 10.1109/77.622233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Clendinen CS et al. , “13C NMR Metabolomics: Applications at Natural Abundance,” Anal. Chem, vol. 86, no. 18, pp. 9242–9250, September. 2014, doi: 10.1021/ac502346h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Clendinen CS, Stupp GS, Ajredini R, Lee-McMullen B, Beecher C, and Edison AS, “An overview of methods using 13C for improved compound identification in metabolomics and natural products,” Front. Plant Sci, vol. 6, 2015, doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Clendinen CS, Pasquel C, Ajredini R, and Edison AS, “13C NMR Metabolomics: INADEQUATE Network Analysis,” Anal. Chem, vol. 87, no. 11, pp. 5698–5706, June. 2015, doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Patterson RE et al. , “Lipotoxicity in steatohepatitis occurs despite an increase in tricarboxylic acid cycle activity,” Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab, vol. 310, no. 7, pp. E484–494, April. 2016, doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00492.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Frelin O et al. , “A directed-overflow and damage-control N-glycosidase in riboflavin biosynthesis,” Biochem. J, vol. 466, no. 1, pp. 137–145, February. 2015, doi: 10.1042/BJ20141237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Thomas JN et al. , “Modeling the Resonance Shifts Due to Coupling Between HTS Coils in NMR Probes,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser, vol. 1559, p. 012022, June. 2020, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1559/1/012022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hoult DI, Richards RE, and Styles P, “A Novel Field-Frequency Lock for a Superconducting Spectrometer,” J. Magn. Reson. 1969, vol. 30, no. 2, Art. no. 2, May 1978, doi: 10.1016/0022-2364(78)90106-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Amouzandeh G, Ramaswamy V, Freytag N, Edison AS, Hornak LA, and Brey WW, “Time and Frequency Domain Response of HTS Resonators for Use as NMR Transmit Coils,” IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond, vol. 29, no. 5, Art. no. 5, August. 2019, doi: 10.1109/TASC.2019.2902522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brey WW, Edison AS, Nast RE, Rocca JR, Saha S, and Withers RS, “Design, construction, and validation of a 1-mm triple-resonance high-temperature-superconducting probe for NMR,” J. Magn. Reson, vol. 179, no. 2, Art. no. 2, April. 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Withers RS, “Inductively coupled superconducting coil assembly,” US5585723A, December. 17, 1996.

- [17].Withers RS, Nast RE, and Anderson WA, “NMR spiral RF probe coil pair with low external electric field,” US7701217B2, April. 20, 2010.

- [18].Ramaswamy V, “Electromagnetic Resonances of Spiral Resonators,” presented at the ASC, Denver, Colorado, Sep. 06, 2016, Accessed: Dec. 17, 2019. [Online]. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brey WW, Johansson ME, and Withers RS, “Method of making nuclear magnetic resonance probe coil,” US5619140A, April. 08, 1997.

- [20].Withers RS, “Nuclear magnetic resonance probe comprising slit superconducting coil with normal-metal overlayer,” US8564294, June. 28, 2011.

- [21].Brey WW, Anderson WA, Wong WH, Fuks LF, Kotsubo VY, and Withers RS, “Nuclear magnetic resonance probe coil,” US5565778A, October. 15, 1996.

- [22].Ramaswamy V, Edison AS, and Brey WW, “Inductively-Coupled Frequency Tuning and Impedance Matching in HTS-Based NMR Probes,” IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 1–5, June. 2017, doi: 10.1109/TASC.2017.2672718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sato K et al. , “Dependences of microwave surface resistance of HTS thin films on applied dc magnetic fields parallel and normal to the substrate,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser, vol. 507, no. 1, p. 012045, May 2014, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/507/1/012045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]