Abstract

Gut bacteria might contribute in early stage of colorectal cancer through the development and advancement of colon adenoma, by which exploring either beneficial bacteria, which are decreased in formation or advancement of colon adenoma and harmful bacteria, which are increased in advancement of colon adenoma may result in implementation of dietary interventions or probiotic therapies to functional means for prevention. Korean fermented kimchi is one of representative probiotic food providing beneficiary microbiota and exerting significant inhibitory outcomes in both APC/Min+ polyposis model and colitis-associated cancer. Based on these backgrounds, we performed clinical trial to document the changes of fecal microbiota in 32 volunteers with normal colon, simple adenoma, and advanced colon adenoma with 10 weeks of fermented kimchi intake. Each amplicon is sequenced on MiSeq of Illumina and the sequence reads were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units using VSEARCH and the Chao Indices, an estimator of richness of taxa per individual, were estimated to measure the diversity of each sample. Though significant difference in α or β diversity was not seen between three groups, kimchi intake significantly led to significant diversity of fecal microbiome. After genus analysis, Acinobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Clostridium sensu, Turicibacter, Gastronaeophillales, H. pittma were proven to be increased in patients with advanced colon adenoma, whereas Enterococcua Roseburia, Coryobacteriaceau, Bifidobacterium spp., and Akkermansia were proven to be significantly decreased in feces from patients with advanced colon adenoma after kimchi intake. Conclusively, fermented kimchi plentiful of beneficiary microbiota can afford significant inhibition of either formation or advancement of colon adenoma.

Keywords: fermented kimchi, microbiota, colon adenoma, colorectal cancer, prevention

Introduction

Colon adenomas are classified as sessile, pedunculated or flat on the basis of endoscopic morphology and colon adenoma can be classified microscopically as either tubular villous or tubulovillous on the basis of their architectural growth pattern. Clinically, advanced colon adenomas are defined as lesions with at least one of the following features, 1 cm in size, villous architecture more than 25%, or high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal adenocarcinoma.(1) A meta-analysis study showed that patients with adenomas with high grade dysplasia were at increased risk for recurrent advanced adenomas compared to patients with adenomas with low-grade dysplasia.(2,3) Though the malignant potential of colon adenomas relates to the size, type, and degree of dysplasia, adenomas more than >2 cm in size have a 10–20% risk of carcinoma at the time of removal, whereas those measuring less than 1 cm have less than 1–2% risk.(4) However, exceptional cases that even smaller size progress to adenocarcinoma exist and no way of definite preventive strategy threatened general population who was diagnosed as simple colon adenoma and made them to perform frequent colonoscopy or led to intake of unnecessary medications/general health medicine.

Meanwhile, the multiple reports that higher numbers of Fusobacterium nucleatum, Enterococcus feacalis, Streptococcus bovis, Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, and Porphyromonas spp. were detected in patients with colon adenoma, from simple adenoma to advanced adenoma, in contrast to samples from the normal or hyperplastic polyp and the contrary results that lower number of Lactobacillus spp., Roseburia spp., and Bifidobacterium spp. were detected in colon adenoma compared to the normal signified the contribution of altered microbiota in formation and progression of colon adenoma rendered us to adopt fecal microbiota analysis as predictive functional analyses based on the candidate bacterial quantity of the adenoma and non-adenoma groups and tool to assess the function of fermented foods relevant to colon adenoma.(5–13) Therefore, the alteration of the microbiota may be a useful to preventing and altering the trajectory of colorectal cancer as well as advancement of colon adenoma,(14,15) usually through intake of fermented foods or probiotics.

Supported with facts that gut microbiota represents a natural defense against various kinds of gastrointestinal diseases and exerts anticarcinogenic effects, maintaining the gut homeostasis and the modulation of intestinal microbiota with probiotics foods, fermented kimchi in the current study, can be basis for either preventing recurrence of colon adenoma or blocking advancement of colon adenoma,(16,17) we have performed clinical trials to explore fecal microbiota changes relevant to probiotic foods and found significant contribution with probiotic kimchi was noted against colon adenoma.

Material and Methods

Bacteria DNA extraction from human stool samples

The human stool sample is filtered through a 40 µm-pore sized cell strainer after being diluted and incubated in 10 ml of PBS for 24 h. To separate the bacteria from human stool, bacteria in stool samples is isolated using centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the pellet is comprised of bacteria. To extract the DNA out of the bacteria, bacteria is boiled for 40 min under 100°C. DNA is extracted by using a DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany); The standard protocol is followed as the kit guide. The DNA from bacteria in each sample is quantified by using QIAxpert system (QIAGEN).

Bacterial metagenomic analysis using DNA from human stool samples

Bacterial genomic DNA was amplified with 16S_V3_F (5'-TCG TCG GCA GCG TCA GAT GTG TAT AAG AGA CAG CCT ACG GGN GGC WGC AG-3') and 16S_V4_R (5'-GTC TCG TGG GCT CGG AGA TGT GTA TAA GAG ACA GGA CTA CHV GGG TAT CTA ATC C-3') primers, which are specific for V3–V4 hypervariable regions of 16S rDNA gene. The libraries were prepared using PCR products according to MiSeq System guide (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and quantified using a QIAxpert (QIAGEN). Each amplicon is then quantified, set equimolar ratio, pooled, and sequenced on MiSeq (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Analysis of bacterial composition in the microbiota

Paired-end reads that matched the adapter sequences were trimmed by cutadapt ver. 1.1.6.(18) The resulting FASTQ files containing paired-end reads were merged with CASPER and then quality filtered with Phred (Q) score based criteria described by Bokulich.(19,20) Any reads were shorter than 350 bp and longer than 550 bp after merging, were also discarded. To identify the chimeric sequences, a reference-based chimera detection step was conducted with VSEARCH against the SILVA gold database.(21,22) Next, the sequence reads were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) using VSEARCH with de novo clustering algorithm under a threshold of 97% sequence similarity. The representative sequences of the OTUs were finally classified using SILVA 132 database with UCLUST (parallel_assign_taxonomy_uclust.py script on QIIME ver. 1.9.1) under default parameters.(23) The Chao Indices, an estimator of richness of taxa per individual, were estimated to measure the diversity of each sample.

Volunteers recruitment and clinical trials

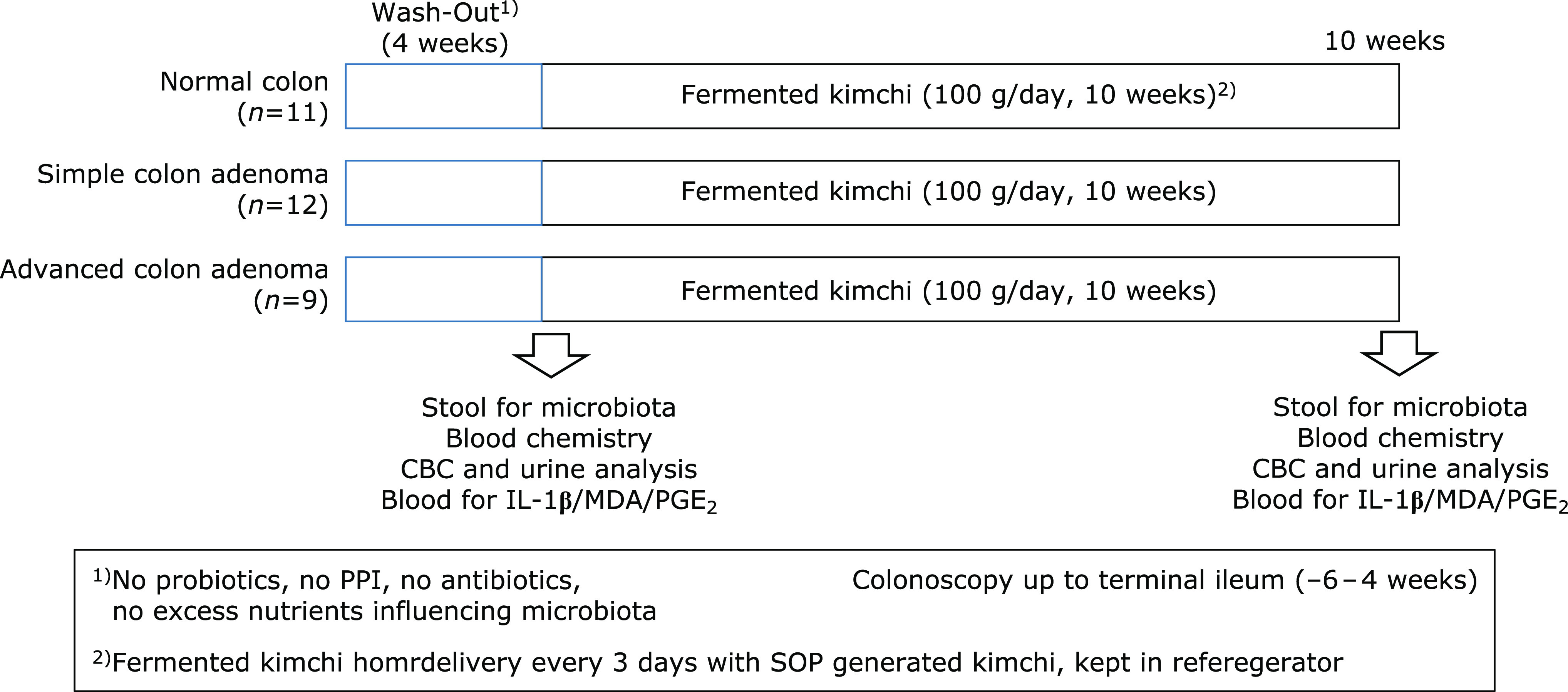

Normal control (healthy control) was defined as subject who underwent screening colonoscopy for health promotion purpose without any symptom and in whom the result of colonoscopy was normal up to terminal ileum. Volunteer subjects with simple colon adenoma and advanced colon adenoma were recruited at clinical trial center located at Digestive Endoscopy Center, Digestive Disease Center, CHA University Bundang Hospital (Seongnam, Korea). The informed consents were obtained from the Digestive Disease Center of Bundang Cha Medical Center (Seongnam, Korea) after explaining the aim and the object of the current study that fermented kimchi showed significant protection from either development or advancement of colon adenoma in mice model [APC/Min+ model developing multiple intestinal neoplasm (MIN) via truncated apc mutation and azoxymethane-initiated, dextran sulfate sodium-promoted colitis-associated cancer model]. As shown in Fig. 1, they were administered with fermented kimchi for 10 weeks after informed consent and stools were donated for microbiota analysis (MD Healthcare, Inc., Seoul, Korea) and blood samplings were saved for biochemical analysis including CBC, biochemistry, and levels of IL-1β, malondialdehyde for lipid peroxidation, and prostaglandin E2. Before starting the kimchi intake, the volunteers were advised not to take any medications like probiotics, proton pump inhibitor, antibiotics, and medications influencing gut microbiota as 4 weeks of wash-out period before taking feces for microbiota analysis. Compliance for taking kimchi was checked above intake more than 90% and kimchi was prepared every 5 days to keep optimal fermentation state. All of these studies were approved with IRB (IRB #18-0201) of CHA University Bundang Hospital. There was no significant difference in mean ages, gender difference, and history of smoking and alcohol among groups on demographic analysis of simple and advanced adenoma. simple colon adenoma in 12 patients [male:female = 4:8, mean ages, 51 ± 3, mean colon adenoma size = 0.8 cm, smoking:non-smoking = 4:8, alcohol:non-alcohol = 6:6, family history of colon cancer:non-family history of colon cancer = 1:11, rectum, descending colon, transverse colon; ascending colon of colon adenoma location = 5, 2, 0, 5, positive stool occult blood (OB) in 1 case], advanced colon adenoma in 9 patients (male:female = 4:5, mean ages, 54 ± 4, mean colon adenoma size = 1.3 cm, smoking:non-smoking = 3:6, alcohol:non-alcohol = 3:6, family history of colon cancer:non-family history of colon cancer = 2:7, rectum, descending colon, transverse colon, ascending colon of colon adenoma location = 4, 1, 1, 3, positive stool OB in 1 case). All volunteers were administered with fermented kimchi (CJ Food, Blossom Park, Suwon, Korea), 100 g/day for 10 weeks, delivered to the home refrigerator every 3 days after generating SOP-recipe kimchi in same condition. All the volunteers were included after informed consent and their compliance for kimchi intake were more than 95%.

Fig. 1.

Clinical trial with fermented kimchi (A) Schematic protocol for fecal microbiota measurement All volunteers were administered with fermented kimchi (CJ Food, Seoul, Korea), 100 g/day for 10 weeks prepared according to SOP recipe, delivered every 3 days to all volunteer home exactly. All the volunteers were included after informed consent and their compliance for kimchi intake were more than 95%.

Kimchi preparation and extracts for in vitro experiment

Kimchi preparation was based on the standardized kimchi recipe of the Kimchi (sKimchi) in CJ Food Research Center, Suwon, Korea. First of all, sKimchi is made of birned baechu cabbage (a kind of Chinese cabbage), red pepper powders, garlic, ginger, anchovy juice, sliced redish, green onion, some sugar, then fermented for some periods yielding lactobacillus like L. plantarum. In addition to these ingredients necessary for sKimchi production, additional supplements such as mustard leaf, Chinese pepper, pear, mushroom, and sea tangle juice instead of anchovy juice were included in cancer preventive kimchi (cpkimchi). Kimchi was prepared every 5 days to keep fermentation and was delivered to house of volunteers on exact day of delivery and keep at refrigerator. 100 g of kimchi was packed and supplied.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of relative abundances (RA) of OTUs and α diversity between groups was performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was considered if the p value was <0.05. The α diversity of microbial composition was measured using the Observed, Chao1, Shannon, Simpson index and rarefied to compare species richness. Statistical analyses were performed with R software (ver. 3.6.0).

Results

α and β Diversity analysis according to colon status, normal colon, simple colon adenoma, and advanced colon adenoma

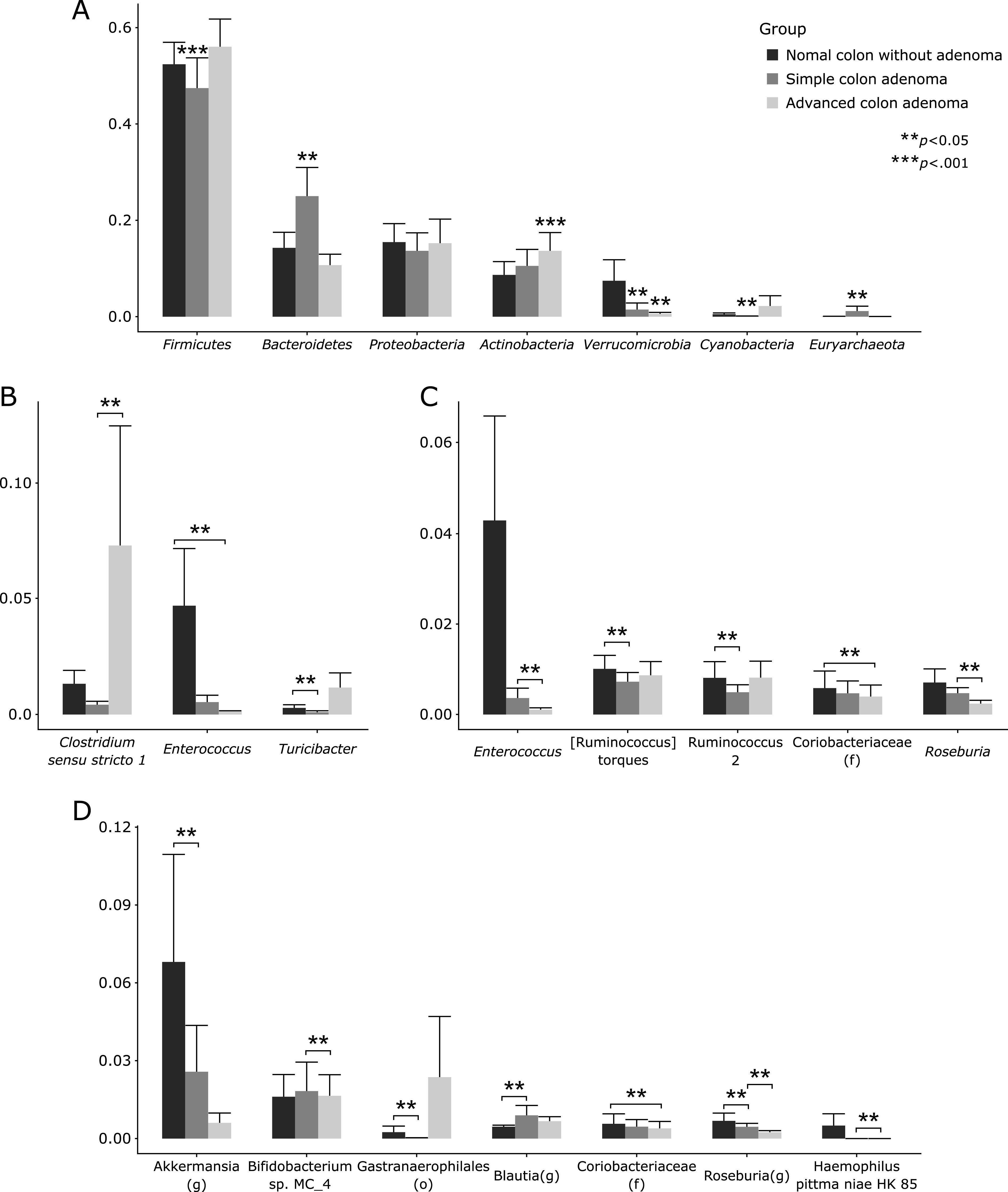

α Diversity is the analysis of species diversity in samples, for which Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indexes were explored in order to describe the diversity features of colorectal community according to colon status, normal healthy colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma, respectively, all were calculated based on OTU species and abundance, respectively in Fig. 2A. In detail, Shannon, diversity indexes used to describe the diversity features of our colorectal community, Chao indexes used to reflect the species richness in the sample, that is, the number of OTU, and Simpson indexes used to reflect community diversity including species richness and species evenness were calculated in Fig. 2 according to patient group.(24,25) Usually, the larger the Shannon index and the smaller the Simpson index, the higher the species diversity in the sample were noted. Regarding α diversity according to colon pathology as shown in Fig. 2A, there was no significant difference in these indexes between normal control, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma. In order to further display differences in species diversity among samples, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used to display differences among samples. If the two samples are close together, the species composition of the two samples is similar. No significant separation in bacterial community composition between normal colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma were seen (Supplemental Fig. 1A*, phylum level and Supplemental Fig. 1B*, genus level). Relative abundance of colon adenoma associated microbiota including microbial composition of normal colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma at the phylum level was shown in Fig. 2B. The most abundant phylum in total samples was Firmicutes (88.9%), followed by followed by Bacteroidetes (62.3%), Proteobacteria (45.7%), and Actinobacteria (23.4%) (Fig. 2B). Conclusively, relative abundance of the phylum level in feces by pyrosequencing showed that there was no significant difference in relative abundance of most abundant phyla among the three groups (p>0.05). In addition, relative abundance of colon adenoma associated microbiota including microbial composition of normal colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma at the genus level was shown in Fig. 2C and Fig. 3. Relative abundance of microbiota among the three groups, normal colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma, in the genus level was shown in Fig. 4 depicting Streptococcus, Citrobacter, and Pseudomonas were significantly increased in advanced adenoma, whereas Fecalibacterium and Akkermansia were significantly decreased in advanced colon adenoma. Individual microbium was compared according to group, which was presented in Fig. 4 that Acinobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Clostridium sensu stricto, Turicibacter, Gastronaeophillales, H. pittma HK B5 were proven to be increased of patients with advanced colon adenoma, wherewas Enterococcua Roseburia, Coryobacteriaceau, Bifidobacterium spp., and Akkermansia were proven to significantly decreased in feces from patients with advanced colon adenoma (Fig. 4). Individual separate Heatmap results compared between group before kimchi and group after kimchi at genus level were shown on Supplemental Fig. 4*.

Fig. 2.

Relative abundance of the phylum level (% similarity) in collected feces samples by pyrosequencing. (A) α Diversity in normal colon, simple colon adenoma, and advanced colon adenoma. (B) Microbiota at phylum levels, heatmap and bar display. (C) Microbiota at genus levels.

Fig. 3.

Relative abundance of the genus level (% similarity) in collected feces samples by pyrosequencing. Significant changes in microbiota among normal colon, simple adenoma, and advanced adenoma after analysis.

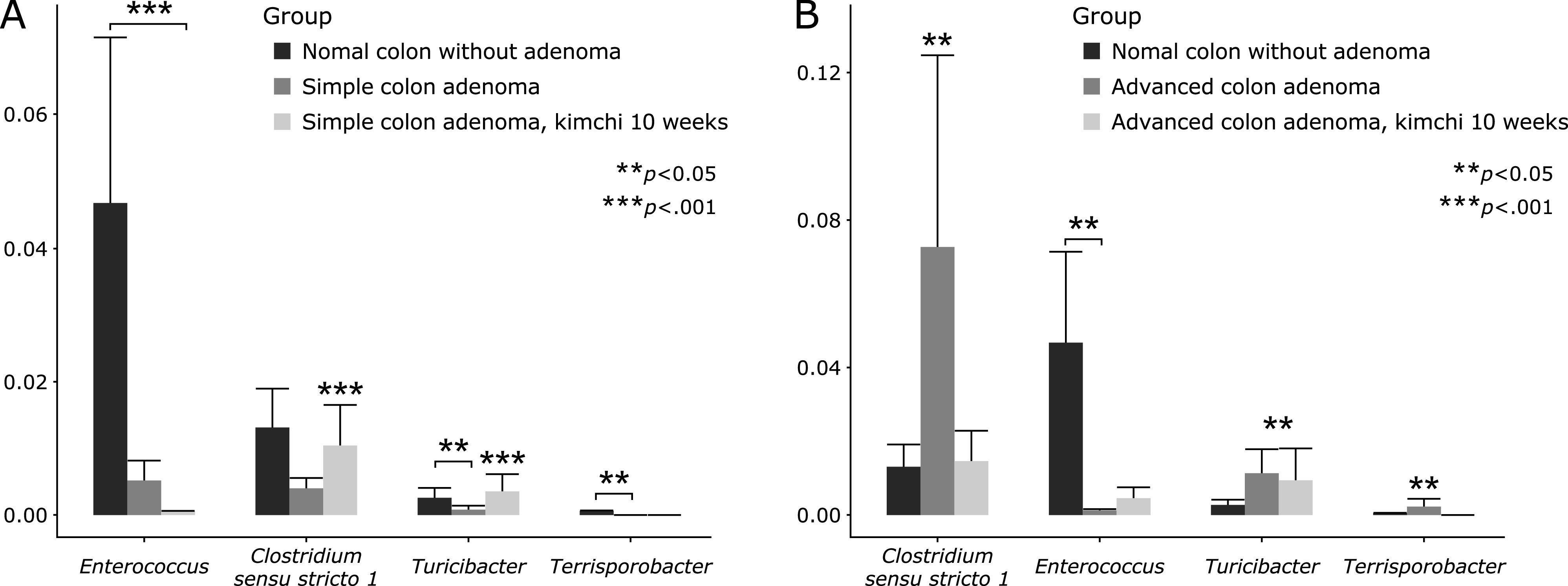

Fig. 4.

Significant microbiota changes at genus level. (A) Between simple adenoma cases before and after kimchi intake. (B) Between advanced adenoma cases before and after kimchi intake.

Evaluation of α and β diversity in the 3 groups of normal control, simple colon adenoma, and advanced colon adenoma after 10 weeks of kimchi intake

The Chao1 Richness index of the fecal microbiota was significant different between normal control and normal control with kimchi intake (p<0.052), while other index of observed, Shannon, and Simpson was changed, but not significance. Similar results were observed between simple colon adenoma control and simple colon adenoma with kimchi intake (p<0.014 observed index and 0.00037 Chao1 Richness index, Fig. 5B), and between advanced colon adenoma control and advanced colon adenoma with kimchi intake (p<0.05 Chao1 Richness index, Fig. 5C). Overall differences in these diversity analyses were shown in Fig. 5D, significant difference in Shanon index with kimchi intake. In order to further display differences in species diversity among samples, PCoA based on the unweighted UniFrac distance metrics is used to display differences among samples. (Supplemental Fig. 2*).

Fig. 5.

α Diversity, phylum and genus level analysis after 10 weeks kimchi intake. (A) α Diversity in normal colon. (B) α Diversity in simple colon adenoma with 10 weeks kimchi intake. (C) α Diversity in advanced colon adenoma with 10 weeks kimchi intake (D) Total comparison of α diversity in all volunteers after 10 weeks of fermented kimchi intake. Universal, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson index illustrated.

Relative abundance of colon adenoma associated microbiota; microbial composition of normal colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma after 10 weeks of kimchi intake at the phylum level

The most abundant phylum in total samples was Firmicutes (90.1%), followed by followed by Bacteroidetes (71.4%), Proteobacteria (43.7%), Actinobacteria (35.7%), Verrucomicrobia (16.6%) (Fig. 6A). Figure 6B showed relative abundance of the phylum level in feces by pyrosequencing and there was no significant difference in relative abundance of most abundant phyla among the three groups (p>0.05). Individual separate Heatmap results compared between group before kimchi and group after kimchi at phylum levels were shown on Supplemental Fig. 3*.

Fig. 6.

Significant changes in microbiota among normal colon, simple adenoma, and advanced adenoma with 10 weeks kimchi intake. (A) Phylum level analysis Heatmap analysis and bar display. (B) Genus levels analysis and bar display.

Relative abundance of colon adenoma associated microbiota; microbial composition of normal colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma at the genus level

Relative abundance of microbiota among the three groups, normal colon, colon with simple adenoma, and colon with advanced adenoma, in the genus level was shown in Fig. 6C depicting Streptococcus, Citrobacter, and Pseudomonas were significantly increased in advanced adenoma, whereas Fecalibacterium and Akkermansia were significantly decreased in advanced adenoma. Individual microbium was compared according to group, which was presented in Fig. 6 that Acinobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Clostridium sensu stricto, Turicibacter, Gastronaeophillales, H. pittma HK B5 were proven to be increased of patients with advanced colon adenoma, wherewas Enterococcua Roseburia, Coryobacteriaceau, Bifidobacterium spp., and Akkermansia were proven to significantly decreased in feces from patients with advanced colon adenoma (Fig. 6). Individual separate Heatmap results compared between group before kimchi and group after kimchi at genus level were shown on Supplemental Fig. 4*.

Changes of IL-1β after kimchi intake

Kimchi intake significantly decreased sera levels of IL-1β We have compared CBC and blood chemistry including cholesterol level, triglyceride level before and after 10 weeks of kimchi intake in all participants and there were no significance differences. Also, we have measured three kinds of parameters, IL-1β, MDA, and PGE2 blood levels and there were significant decreases in IL-1β in patients with advanced colon adenoma after kimchi intake (p<0.05, Supplemental Fig. 5A*), while there were no significant changes in MDA and PGE2 between levels before kimchi intake and after kimchi intake.

Discussion

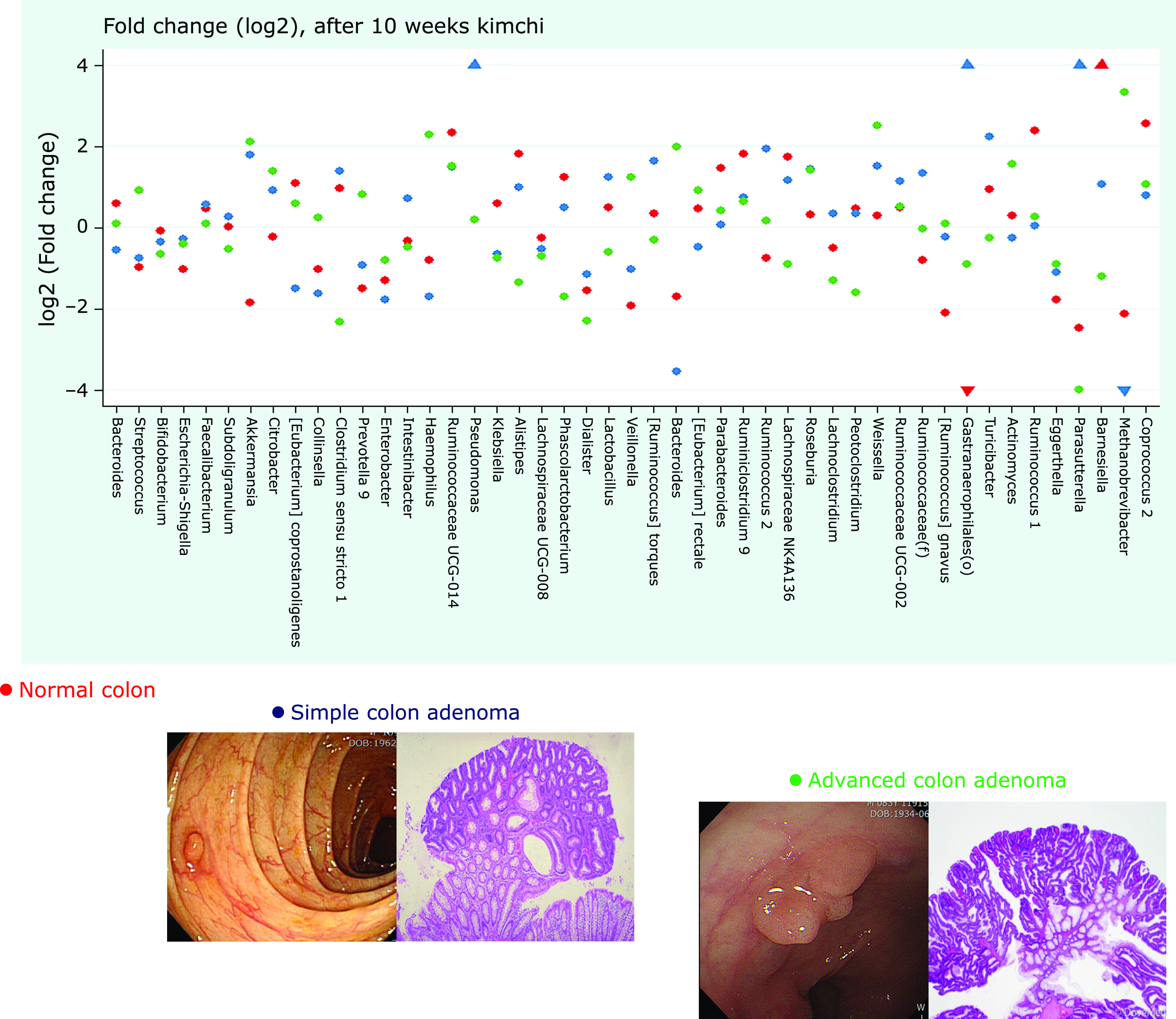

Well-fermented kimchi showed significant inhibitory actions against intestinal adenoma formation as well as colitic cancer development,(26) during which we could identify significant changes in fecal microbiota from the current study after clinical trial of fermented kimchi in patients with colon adenoma. Kimchi effectively changed fecal microbiota implicated in colon either adenoma formation or adenoma advancement. Detailed microbiota changes were displayed in Fig. 7, explaining the contributive role of fermented kimchi intake in either preventing colon adenoma or inhibiting the progression of simple colon adenoma. The most abundant phylum in total samples was Proteobacteria (55.6%), followed by Firmicutes (27.4%) and Bacteroidetes (11.6%). Though there was no significant difference in relative abundance of the phylum level among the four groups, Fusobacterium nucleatum, known to be frequently detected during colorectal carcinogenesis, was found in patient with advanced adenoma. The diversity of mucosal communities of patients with adenoma was higher in patients with adenoma than that of healthy control and its diversity varies significantly with kimchi intake. Though we should wait for long-term effect of kimchi intake on inhibitory action of colon adenoma, together with previous publication that fermented kimchi intake significantly inhibited colon adenoma as well as colitic cancer and current investigation to explore microbiota changes with kimchi intake in patients with colon adenoma,(26) we could conclude fermented kimchi can be of potential nutritional intervention to inhibit colon adenoma.

Fig. 7.

Schematic conclusive results explaining the significant contribution of fermented kimchi in either inhibition of colon adenoma formation or advancement of colon adenoma with 10 weeks of kimchi intake. Red dot denoted normal colon, blue dot simple adenoma, and green dot advanced adenoma after 10 weeks of fermented kimchi, included within log2 significance.

Here in this investigation, we could include one patient, 17 years old female diagnosed as attenuated type of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) presenting with multiple polyps in stomach and colon, who participated in 10 weeks of kimchi intake and fortunately have very positive results showing changes of microbiota. As reported in Science journal, Dejea et al.(27) identified patchy bacterial biofilms composed predominately of Escherichia coli and B. fragilis in patients with FAP and genes for colibactin and B. fragilis toxin were highly enriched in FAP patients. Under the hypothesis that the removal of colon adenoma and carcinoma can change fecal microbiota, 67 individuals (22 patients with adenoma, 19 patients with advanced adenoma, and 26 patients with colon cancer) were subjected to pyrosequencing and there were small changes to the bacterial community associated with adenoma or advanced adenoma and large changes associated with carcinoma. Although the adenoma and carcinoma models could reliably differentiate between the pre- and post-treatment samples (p<0.001), the advanced-adenoma model could not.(28)

Since the gut microbiome may be an important factor in the development of colon adenoma as well as CRC, exploring microbial community can be tool as a potential screen for early-stage disease that specific analysis of multiple aspects of the microbiome composition provides reliable detection of both precancerous and cancerous lesions.(8,29,30) However, the need for more cross-sectional studies with diverse populations, linkage to other stool markers, dietary data, large scale of Cohort, and personal health information is mandatory.(10,31) As real world data regarding microbiota in adenoma or CRC, adenoma mucosal and adjacent normal colonic mucosal biopsies were profiled using the Illumina sequencing platform, after which taxonomic analysis revealed that abundance of eight phyla including Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Candidate-division TM7, and Tenericutes was noted, similar finding with ours results that significantly different and Lactococcus and Pseudomonas were enriched in adenoma tissue (Fig. 3 and 4), whereas Enterococcus, Bacillus, and Solibacillus were reduced, while other study showed similar result that Fusobacterium nucleatum, E. faecalis, S. bovis, Enterotoxigenic B. fragilis (ETBF), and Porphyromonas spp. as well as depletion of some microbes, consisting Roseburia spp., Eubacterium spp., Lactobacillus spp., and Bifidobacterium spp.,(6,32–34) signifying changes in bacterial community composition might affect colon neoplasia.(5,35) In another study using biofilm in the colon, PCoA revealed that biofilm communities between normal mucosa and distant from the tumor cluster was different, suggesting colon mucosal biofilm detection may predict risk for CRC.(36) As another sources for investigation, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) colorectal tissue samples from patients with CRC and paired normal tissues were tested for the presence and bacterial load of S. gallolyticus, F. nucleatum, and B. fragilis by real time-PCR, but association was documented between Prevotella and Acinetobacter after pyrosequencing, telling the limitation of specimen kinds.(37)

Since better understanding of the role of gut microbiota in either colon adenoma progression or CRC carcinogenesis could provide promising new directions to either prevention or treatment, the discovery of novel biomarkers of the gut microbiome might be of outmost importance.(38–40) Microorganisms affected the onset and progression of CRC via acceleration of chronic mutagenic inflammation, the biosynthesis of genotoxins that interfere with cell cycle regulation, the production of toxic metabolites, activation of carcinogenic diet compounds, and robust oxidative genotoxic stress, by which altered gut microbiota may allow the outgrowth of bacterial populations that induce genomic mutations or exacerbate tumor-promoting inflammation, concluding large metagenomic studies in CRC-associated microbiome signature significantly tells fundamental role of intestinal microbiota in adenoma-carcinoma sequence.(41) As like in the current investigation denoted in advanced colon adenoma, S. bovis, Helicobacter pylori, B. fragilis, E. faecalis, C. septicum, Fusobacterium spp., and Escherichia coli were reported to be pathogen responsible for colon tumorigenesis including adenocarcinoma.(14,16) As results, modulation of intestinal microbiota can alter colitis-associated cancer susceptibility as evidenced that the severity of chronic colitis directly correlates to colitic cancer, during which bacterial-induced inflammation drives progression from adenoma to invasive carcinoma.(42,43)

In this study, after informed consent, 5 ml bloods were obtained in all volunteers before and after kimchi intake, by which we had additional measurements of serum levels of IL-1β, MDA, and PGE2 in all cases and significant differences in IL-1β were noted (Supplemental Fig. 5*). We have conducted RNAseq analysis in animal model of colitis-associated cancer with pellet diet containing fermented kimchi and found significant changes in COX-2, 15-PGDH, oxidative stress related genes, and inflammasomes including IL-1β. Based on these in vivo finding, we decided to measure the changes of serum IL-1β, MDA, and PGE2 and found the significant decreases in IL-1β after kimchi intake. Since IL-1β promotes cell growth, stemness and invasiveness of colon cancer cells as well as colitic cancer,(44,45) serum levels as well as genetic polymorphisms, IL-1RN +2018T>C, can influence colon carcinogenesis.(46,47)

Though we have omitted results regarding the results from cross intake (10 weeks of fermented kimchi followed with non-fermented kimchi or reverse) of fermented kimchi, we could realize fermented kimchi yielded positive changes in patients with colon adenoma, signifying the importance of fermentation in preventing colon adenoma. Small in size, short-follow up interval, and analysis in phylum and genus level, but combined with our in vitro and in vivo model study, we dare to conclude long-term intake of well-fermented kimchi can be anticipating strategy either to prevent adenoma formation or to block advancement of colon adenoma. Though fermented kimchi intake was dealt in this study, food we consume is essential for energy, but also provides a diverse community of microbiota within our GI tract.(44) Therefore, more understanding of the nutrient–microbiota interplay and large-scale studies to evaluate the efficacy of dietary modification and gut microbiota modulation in reversing dysbiosis and restoring health could offer novel preventative and/or therapeutic strategies. However, considering different ethnicity, different dietary style, and different cultural habits, our study should be extended more to reach to conclusion.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: JMP and KBH; acquisition of data: JMP, WHL, HS, DYL, SHC; analysis and statistical analysis: JMP, WHL, and KBH; interpretation of data: HS, JYO and KBH; drafting of manuscript: KBH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (IPET) through High Value-added Food Technology Development Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (116015-03-1-CG000).

Abbreviations

- CAC

colitis-associated cancer

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- FAP

familial adenomatous polyposis

- FFPE

formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MIN

multiple intestinal neoplasia

- PCoA

principal coordinate analysis

- OUTs

operational taxonomic units

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- STRING

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins

- RA

relative abundancy

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Naini BV, Odze RD. Advanced precancerous lesions (APL) in the colonic mucosa. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013; 27: 235–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelman HD. Con: high-grade dysplasia and villous features should not be part of the routine diagnosis of colorectal adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 1329–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG. The advanced adenoma as the primary target of screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2002; 12: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinya H, Wolff WI. Morphology, anatomic distribution and cancer potential of colonic polyps. Ann Surg 1979; 190: 679–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rezasoltani S, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Dabiri H, Akhavan Sepahi A, Modarressi MH, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E. The association between fecal microbiota and different types of colorectal polyp as precursors of colorectal cancer. Microb Pathog 2018; 124: 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dulal S, Keku TO. Gut microbiome and colorectal adenomas. Cancer J 2014; 20: 225–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weir TL, Manter DK, Sheflin AM, Barnett BA, Heuberger AL, Ryan EP. Stool microbiome and metabolome differences between colorectal cancer patients and healthy adults. PLoS One 2013; 8: e70803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters BA, Dominianni C, Shapiro JA, et al. The gut microbiota in conventional and serrated precursors of colorectal cancer. Microbiome 2016; 4: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goedert JJ, Gong Y, Hua X, et al. Fecal microbiota characteristics of patients with colorectal adenoma detected by screening: a population-based study. EBioMedicine 2015; 2: 597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zackular JP, Rogers MA, Ruffin MT 4th, Schloss PD. The human gut microbiome as a screening tool for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014; 7: 1112–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Q, Liang S, Jia H, et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCoy AN, Araújo-Pérez F, Azcárate-Peril A, Yeh JJ, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Fusobacterium is associated with colorectal adenomas. PLoS One 2013; 8: e53653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale VL, Chen J, Johnson S, et al. Shifts in the fecal microbiota associated with adenomatous polyps. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017; 26: 85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandal P. Molecular mechanistic pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis associated with intestinal microbiota. Anaerobe 2018; 49: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013; 14: 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagnière J, Raisch J, Veziant J, et al. Gut microbiota imbalance and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22: 501–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zackular JP, Baxter NT, Chen GY, Schloss PD. Manipulation of the gut microbiota reveals role in colon tumorigenesis. mSphere 2015; 1: e00001-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kechin A, Boyarskikh U, Kel A, Filipenko M. cutPrimers: a new tool for accurate cutting of primers from reads of targeted next generation sequencing. J Comput Biol 2017; 24: 1138–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon S, Lee B, Yoon S. CASPER: context-aware scheme for paired-end reads from high-throughput amplicon sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics 2014; 15 Suppl 9: S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods 2013; 10: 57–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016; 4: e2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41: D590–D596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 2010; 7: 335–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu W, Zhang R, Shu R, et al. Study of the relationship between microbiome and colorectal cancer susceptibility using 16SrRNA sequencing. Biomed Res Int 2020; 2020: 7828392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu J, Feng Q, Wong SH, et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut 2017; 66: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han YM, Kang EA, Park JM, et al. Dietary intake of fermented kimchi prevented colitis-associated cancer. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2020; 67: 263–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dejea CM, Fathi P, Craig JM, et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science 2018; 359: 592–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sze MA, Schloss PD. Erratum for Sze and Schloss, “Looking for a signal in the noise: revisiting obesity and the microbiome”. mBio 2017; 8: e01995-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mangifesta M, Mancabelli L, Milani C, et al. Mucosal microbiota of intestinal polyps reveals putative biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 13974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon H, Kim N, Park JH, et al. Comparisons of gut microbiota among healthy control, patients with conventional adenoma, sessile serrated adenoma, and colorectal cancer. J Cancer Prev 2017; 22: 108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narayanan V, Peppelenbosch MP, Konstantinov SR. Human fecal microbiome-based biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014; 7: 1108–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol 2014; 10: 766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonnenburg JL, Fischbach MA. Community health care: therapeutic opportunities in the human microbiome. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 78ps12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu K, Jiang B. Analysis of mucosa-associated microbiota in colorectal cancer. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23: 4422–4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu Y, Chen J, Zheng J, et al. Mucosal adherent bacterial dysbiosis in patients with colorectal adenomas. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 26337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dejea CM, Wick EC, Hechenbleikner EM, et al. Microbiota organization is a distinct feature of proximal colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111: 18321–18326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bundgaard-Nielsen C, Baandrup UT, Nielsen LP, Sørensen S. The presence of bacteria varies between colorectal adenocarcinomas, precursor lesions and non-malignant tissue. BMC Cancer 2019; 19: 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manzat-Saplacan RM, Mircea PA, Balacescu L, Chira RI, Berindan-Neagoe I, Balacescu O. Can we change our microbiome to prevent colorectal cancer development? Acta Oncol 2015; 54: 1085–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mo Z, Huang P, Yang C, et al. Meta-analysis of 16S rRNA microbial data identified distinctive and predictive microbiota dysbiosis in colorectal carcinoma adjacent tissue. mSystems 2020; 5: e00138-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mori G, Rampelli S, Orena BS, et al. Shifts of faecal microbiota during sporadic colorectal carcinogenesis. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 10329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, Moschen AR. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 2018; 33: 954–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uronis JM, Muhlbauer M, Herfarth HH, Rubinas TC, Jones GS, Jobin C. Modulation of the intestinal microbiota alters colitis-associated colorectal cancer susceptibility. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Mühlbauer M, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 2012; 338: 120–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vipperla K, O'Keefe SJ. Diet, microbiota, and dysbiosis: a ‘recipe’ for colorectal cancer. Food Funct 2016; 7: 1731–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hai Ping P, Feng Bo , Li L, Nan Hui Y, Hong Z. IL-1β/NF-κB signaling promotes colorectal cancer cell growth through miR-181a/PTEN axis. Arch Biochem Biophys 2016; 604: 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian N, Chen X, Han S, et al. Circulating IL-1beta levels, polymorphisms of IL-1β, and risk of cervical cancer in Chinese women. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2010; 136: 709–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burada F, Dumitrescu T, Nicoli R, et al. IL-1RN +2018T>C polymorphism is correlated with colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep 2013; 40: 2851–2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.