Abstract

There are no reports regarding the efficacy of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor (DPP4i) administrations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of those drugs in such patients. NAFLD patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus were enrolled in this single center double-blind randomized prospective study, and allocated to receive either dapagliflozin (SGLT2i) or teneligliptin (DPP4i) for 12 weeks. Laboratory variables and body compositions were assessed at the baseline and end of treatment. The primary endpoint was alanine aminotransferase (ALT) reduction level at the end of treatment. Twenty-two eligible patients (dapagliflozin group, n = 12; teneligliptin group, n = 10) were analyzed. In both groups, the serum concentration of ALT was significantly decreased after treatment (p<0.05). Multiple regression analysis results showed that decreased body weight of patients with dapagliflozin administration was significantly related to changes in total body water and body fat mass. Administration of dapagliflozin or teneligliptin decreased the serum concentration of ALT in NAFLD patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus. With dapagliflozin, body weight decreased, which was related to changes in total body water and body fat mass (UMIN000027304).

Keywords: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, dapagliflozin, teneligliptin, alanine aminotransferase

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common type of chronic liver disease and affects up to 25% of the global population.(1,2) NAFLD encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions, including nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.(3,4) Liver fibrosis progression has been reported to contribute to mortality from cardiovascular and liver-related disease in these patients.(5,6) A previous investigation showed that a reduction in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of greater than 30% in patients with NASH can prevent liver histological progression including fibrosis,(7) and another found that body weight loss greater than 10% through changes in diet and lifestyle habits improved histology findings such as fibrosis in NASH patients.(8) Although a pharmacological approach is often necessary to treat NAFLD patients who fail to sufficiently reduce their body weight, there are no approved pharmacotherapies for these patients.(9)

Antidiabetic drugs are widely used for NAFLD patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).(10) Those include dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i), which have been approved for treatment of T2DM, and shown to block DPP4 and prolong the biological activity of incretin hormones, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), leading to improvement in glucose tolerance.(11) In small clinical trials of sitagliptin, a DPP4i used for treatment of NAFLD with T2DM, reduction in plasma ALT levels was found in some,(12,13) but not all.(14–17) In another study, the DPP4i vildagliptin was shown to reduce plasma ALT levels in NAFLD patients without a history of T2DM, though 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) findings were not used to distinguish those with T2DM.(18) It has also been reported that treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) can prevent reabsorption of glucose in the kidneys and increase urinary excretion of glucose,(19) and several members of this class of drug have been approved for treatment of T2DM patients. Furthermore, several recent reports have shown that SGLT2i drugs including dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, canagliflozin, ipragliflozin, and luseogliflozin have therapeutic efficacy for treatment of NAFLD with T2DM.(20–31) Nearly all of those studies found that SGLT2i use reduced plasma ALT level and body weight.

To date, no known studies have evaluated the effects of SGLT2i or DPP4i therapy for NAFLD patients without T2DM. Here, we evaluated the effects of dapagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, and teneligliptin, a DPP4 inhibitor, in patients with NAFLD and without T2DM. Each was administrated for 12 weeks and therapeutic effects were evaluated based on serum biochemistry parameters, body composition, blood pressure, and hand grip strength.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a single center double-blind randomized prospective study. Dapagliflozin (5 mg) or teneligliptin (20 mg) was administered once daily for 12 weeks, with no formal sample size calculation performed.

The Shimane University Hospital clinical trial pharmacy team randomized patients into either dapagliflozin or teneligliptin groups 1:1, stratified by gender, using computer-generated numbers. Blinding and allocation concealment were maintained by use of identical-looking bottles and capsules, in which dapagliflozin or teneligliptin were compounded by the hospital pharmacy. Physicians and all other study personnel were also blinded to drug allocation. Unblinding of treatment allocation was done only all study procedures were completed in all study patients.

This clinical study was performed after obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of Shimane University Faculty of Medicine (approval number: 2629) as well as written informed consent from all participating patients. The protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and applicable laws and requirements. The trial was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network under registration number UMIN000027304.

Patients and administration of drugs

Patients with NAFLD and without T2DM were determined based on the following criteria: (1) presence of hepatorenal contrast and increased hepatic echogenicity in abdominal ultrasonography findings obtained using a 3.5-MHz transducer (ARIETTA S70; Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan),(32) (2) daily alcohol consumption lower than 20 g/day; (3) negative for Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, and drug-induced liver injury, as well as the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen, and anti-HCV, antinuclear, and antimitochondrial antibodies; (4) 75-g OGTT findings, with plasma glucose (PG) concentrations measured at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. T2DM, impaired glucose tolerance/impaired fasting glucose (IGT/IFG), and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) were defined in accordance with the WHO criteria.(33) The main inclusion criteria were age ≥20 years, NAFLD without T2DM, and ALT ≥31 and <200 IU/L, while the main exclusion criteria were the presence of severe heart, liver, or kidney disease. Patients were also screened for metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Metabolic syndrome was defined as previously described,(34,35) with minor modifications. Specifically, subjects with at least 3 of the following 5 clinical measurement conditions were considered to have metabolic syndrome: (1) central obesity (waist circumference ≥85 cm in males, ≥90 cm in females), (2) elevated blood pressure (systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg) or taking an antihypertension medication, (3) elevated fasting blood glucose level (≥110 mg/dl) or taking a hypoglycemia medication, (4) decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level (<40 mg/dl), and (5) hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dl) or taking a lipid-lowering medication. After the baseline assessments, the patients were prescribed once-daily dapagliflozin at 5 mg or teneligliptin at 20 mg for 12 weeks. No drugs were changed during the period at least 6 months before this study until the end of the study period.

Determination of body composition, grip strength, and blood pressure

Body composition measurements were performed using an InBody720 analyzer (Biospace Inc., Tokyo, Japan), which has recently been developed for determining body composition in NAFLD patients.(27,36) The output values of the InBody720 include total body water, protein, mineral, and body fat mass, with the sum of these values used as body weight. Hand grip strength and blood pressure was measured at the baseline and week 12.

Blood biochemistry

Serum liver and metabolic variable testing included AST, ALT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), ferritin, type IV collagen 7s, fibrosis-4 index, FPG, fasting insulin (insulin), homeostasis model assessment parameter of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), HDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides, uric acid, adiponectin, and leptin. In addition, laboratory tests were performed for high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatine (Cr), estimated glomerular filtrated rate (estimated GFR), hematocrit (HT), red blood cell count (RBC), and hemoglobin (Hb). HOMA-IR was calculated using the following formula: insulin (µU/ml) × FPG (mg/dl)/405.(37) Fibrosis-4 index values were calculated as: [age (years) × AST (U/L)]/[platelet count (109/L) × ALT (U/L)1/2].(38)

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the two study groups were summarized using mean ± SD for continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using the BellCurve for Excel statistical analysis software package, ver. 2.14 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Comparisons between the groups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney’s U test for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare values obtained at baseline with those obtained at week 12 for patients who completed the study. Comparisons between the dapagliflozin and teneligliptin groups were made using unpaired t tests. The Spearman’s correlation test was used to evaluate correlations between change of body weight with total body water, protein, mineral, and body fat mass changes. The Multivariable regression analysis was performed to assess the association between change in body weight with total body water, protein, mineral, and body fat mass changes. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance as compared to the baseline value.

Results

General characteristics of patients

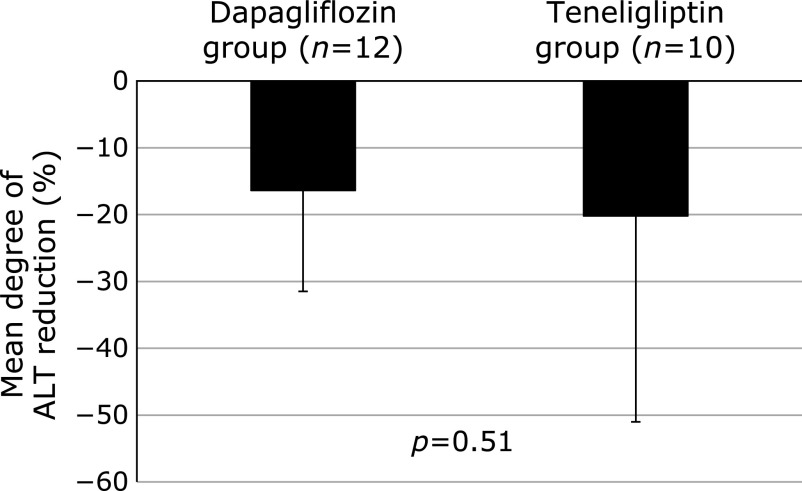

Between May 2017 and January 2018, we randomly assigned 26 NAFLD patients without T2DM to receive dapagliflozin (n = 13) or teneligliptin (n = 13) (Fig. 1). Of the 13 patients in the dapagliflozin group, 1 was excluded because of an ALT level <31 U/L, while 3 of 13 in the teneligliptin group were excluded for a PG level >200 mg/dl at 120 min in 75g-OGTT results. Thus, 12 patients (8 males, 4 females) were included in the dapagliflozin group and 10 (7 males, 3 females) in the teneligliptin group, and their results were analyzed. All patients included in the analyses successfully completed the study protocol.

Fig. 1.

Patients flow and reasons for withdrawal from the study. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; PG, plasma glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients. Among the various patient background factors and laboratory results investigated, only aspartate aminotransferase (AST) [42.3 ± 12.6 (median ± SD) vs 57.8 ± 11.4 mg/dl, p = 0.01], GGT (46.0 ± 30.0 vs 90.5 ± 44.6 mg/dl, p<0.01), and hsCRP (0.16 ± 0.12 vs 0.06 ± 0.04 mg/dl, p<0.01) were significantly different between the dapagliflozin and teneligliptin groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients

| Dapagliflozin group | Teneligliptin group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male:female) | 8:4 | 7:3 | 0.87 |

| Age (years) | 51.6 ± 12.6 | 41.8 ± 16.5 | 0.12 |

| Metabolic syndrome (%) | 4 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | 0.87 |

| Hypertension (%) | 9 (75) | 5 (50.0) | 0.22 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 4 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | 0.87 |

| NGT (%) | 3 (25) | 3 (30) | 0.79 |

| IGT/IFG (%) | 9 (75) | 7 (70) | 0.79 |

| Body weight (kg) | 76.5 ± 20.7 | 78.9 ± 15.7 | 0.55 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 4.3 | 28.7 ± 4.4 | 0.62 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 95.0 ± 10.7 | 94.9 ± 9.6 | 0.98 |

| Total body water (L) | 37.9 ± 11.0 | 37.4 ± 7.4 | 0.82 |

| Protein (kg) | 10.2 ± 3.1 | 10.1 ± 2.1 | 0.84 |

| Mineral (kg) | 3.48 ± 1.04 | 3.45 ± 0.70 | 0.72 |

| Body fat mass (kg) | 25.0 ± 8.2 | 28.0 ± 8.8 | 0.36 |

| Percent body fat (%) | 32.8 ± 7.2 | 35.2 ± 6.0 | 0.21 |

| Skeletal muscle mass (kg) | 28.7 ± 9.2 | 28.4 ± 6.3 | 0.84 |

| Percent skeletal muscle (%) | 37.3 ± 4.8 | 36.0 ± 3.8 | 0.29 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126.1 ± 10.7 | 121.8 ± 10.4 | 0.37 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.3 ± 7.9 | 73.6 ± 3.8 | 0.55 |

| Right hand grip strength (kg) | 35.0 ± 14.0 | 35.8 ± 16.7 | 0.90 |

| Left hand grip strength (kg) | 32.1 ± 13.9 | 32.9 ± 13.2 | 0.95 |

| AST (U/L) | 42.3 ± 12.6 | 57.8 ± 11.4 | 0.01 |

| ALT (U/L) | 75.8 ± 40.7 | 99.0 ± 34.1 | 0.06 |

| GGT (U/L) | 46.0 ± 30.0 | 90.5 ± 44.6 | <0.01 |

| Ferritin (ng/dl) | 138.3 ± 62.9 | 106.1 ± 49.8 | 0.24 |

| Type IV collagen 7s (ng/ml) | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 0.12 |

| Fibrosis-4 index | 1.10 ± 0.36 | 1.16 ± 0.30 | 0.82 |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 100.3 ± 6.8 | 95.3 ± 6.6 | 0.84 |

| Insulin (µU/ml) | 13.1 ± 6.0 | 18.6 ± 7.3 | 0.07 |

| HOMA-IR | 3.22 ± 1.40 | 4.44 ± 1.93 | 0.13 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 0.59 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 53.8 ± 9.5 | 47.8 ± 8.0 | 0.17 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 144.3 ± 24.4 | 128.7 ± 33.8 | 0.18 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 146.8 ± 44.3 | 135.1 ± 72.8 | 0.17 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 0.49 |

| Adiponectin (µg/ml) | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 3.2 | 0.11 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 32.0 ± 22.6 | 30.2 ± 17.3 | 0.95 |

| hsCRP (mg/dl) | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | <0.01 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 14.4 ± 2.4 | 13.2 ± 5.1 | 0.15 |

| Cr (mg/dl) | 0.72 ± 0.18 | 0.67 ± 0.16 | 0.60 |

| Estimated GFR† (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 86.7 ± 20.4 | 100.1 ± 20.9 | 0.22 |

| HT (%) | 45.1 ± 3.0 | 46.3 ± 4.9 | 0.43 |

| RBC (×104/µl) | 493 ± 26 | 516 ± 66 | 0.55 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 14.9 ± 1.1 | 15.5 ± 1.8 | 0.25 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 246 ± 48 | 222 ± 62 | 0.39 |

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD or number (%). BMI, body mass index; AST, asparete aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assement of insulin resistance; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatine; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HT, hematocrit; RBC, red blood cell count; Hb, hemoglobin. †Calculation of estimated GFR based on modification of diet in renal disease formula; estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) = 194 × serum creatinine (mg/dl)–1.094 × age (years)–0.287 × (0.739, if female).

Changes in liver tests

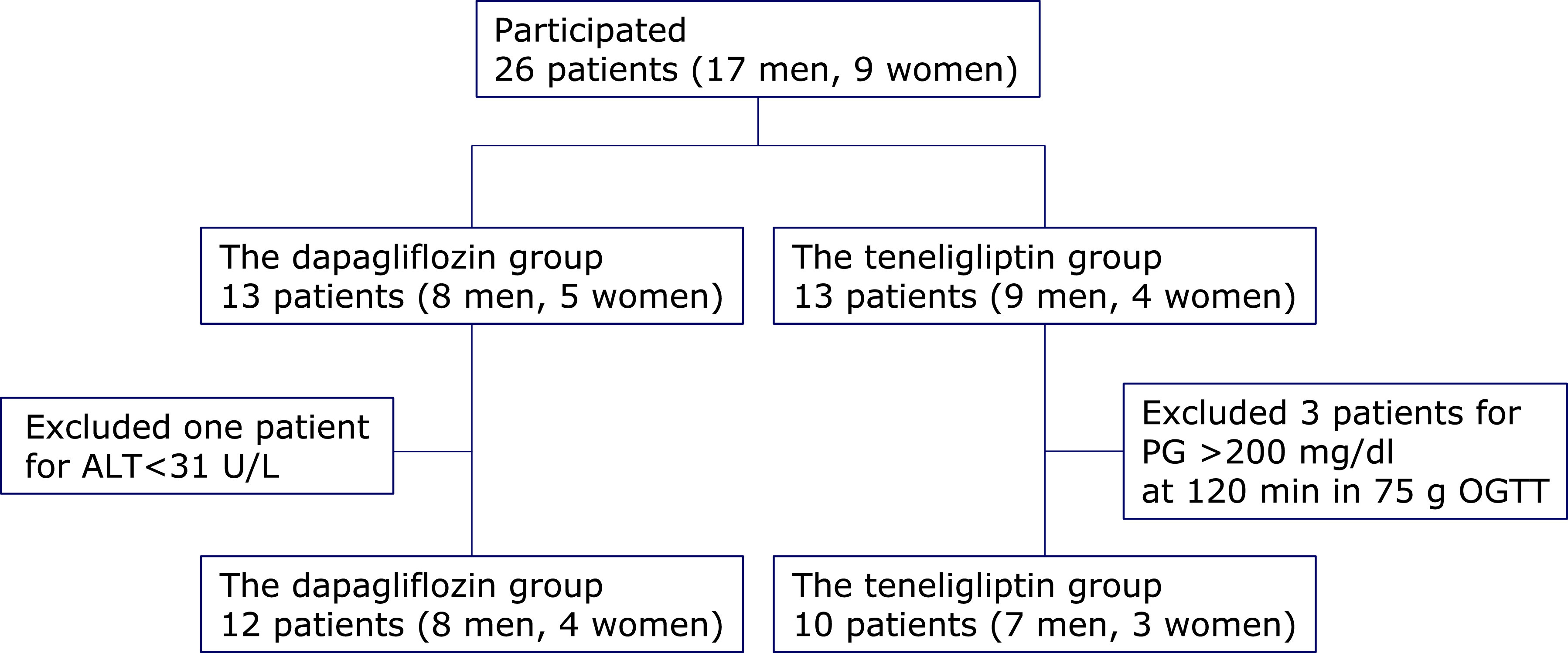

There was no significant difference for degree of ALT reduction at post-treatment between the dapagliflozin (–16.4 ± 15.1%) and teneligliptin (–20.2 ± 30.8%) groups (Fig. 2). In the dapagliflozin group, AST and ALT levels were decreased from the baseline values of 42.3 ± 1.6 U/L and 75.8 ± 40.7 U/L, respectively, to 37.3 ± 13.8 U/L (p<0.05) and 66.8 ± 49.1 U/L (p = 0.02), respectively, at post-treatment, while those in the teneligliptin group were decreased from the baseline values of 57.8 ± 11.4 U/L and 99.0 ± 34.1 U/L, respectively, to 45.4 ± 15.5 U/L (p = 0.04) and 75.3 ± 33.0 U/L (p<0.05), respectively after treatment (Table 2). Furthermore, serum ferritin concentrations in both groups were significantly decreased from the baseline values of 138.3 ± 62.9 ng/dl and 106.1 ± 49.8 ng/dl, respectively, to 102.3 ± 63.4 ng/dl (p = 0.02) and 80.1 ± 45.9 ng/dl (p<0.01), respectively, at post-treatment. There were no significant changes in serum concentrations of GGT, type IV collagen 7s, or fibrosis-4 index in either group. Additionally, evaluations of hepatic steatosis using abdominal ultrasound revealed no clear changes in any of the enrolled patients.

Fig. 2.

Mean degree of ALT reduction. No significant difference was observed for degree of ALT reduction after 12 weeks between the dapagliflozin (–16.4 ± 15.1%) and teneligliptin (–20.2 ± 30.8%) groups.

Table 2.

Changes in laboratory variables after 12 weeks of treatment with dapagliflozin vs teneligliptin

| Dapagliflozin group (n = 12) |

Teneligliptin group (n = 10) |

Difference (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-treatment | Baseline | Post-treatment | |||

| Liver tests | ||||||

| AST (U/L) | 42.3 (1.6) | 37.3 (13.8)* | 57.8 (11.4) | 45.4 (15.5)* | 7.4 (3.4, 18.2) | |

| ALT (U/L) | 75.8 (40.7) | 66.8 (49.1)* | 99.0 (34.1) | 75.3 (33.0)* | 14.7 (–7.1, 36.5) | |

| GGT (U/L) | 46.0 (30.0) | 42.6 (35.5) | 90.5 (44.6) | 85.9 (63.9) | 1.2 (–31.5, 33.8) | |

| Ferritin (ng/dl) | 138.3 (62.9) | 102.3 (63.4)** | 106.1 (49.8) | 80.1 (45.9)** | 10.0 (–10.8, 30.8) | |

| Type IV collagen 7s (ng/ml) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.6) | 4.6 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.2) | 0.1 (–0.6, 0.7) | |

| Fibrosis-4 index | 1.10 (0.36) | 1.04 (0.31) | 1.15 (0.30) | 1.37 (1.33) | 0.28 (–0.73, 1.28) | |

| Metabolic laboratory variables | ||||||

| FPG (mg/dl) | 100.3 (6.8) | 100.0 (7.5) | 95.3 (6.6) | 98.5 (7.5) | 3.4 (–2.0, 8.7) | |

| Insulin (µU/ml) | 13.1 (6.0) | 11.0 (5.7) | 18.6 (7.3) | 19.9 (15.1) | 3.4 (–4.4, 11.2) | |

| HOMA-IR | 3.22 (1.40) | 2.70 (1.43) | 4.44 (1.93) | 5.02 (4.19) | 1.09 (–1.10, 3.28) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.90 (0.36) | 5.76 (0.24)* | 5.82 (0.23) | 5.66 (0.18)* | 0.02 (–0.16, 0.19) | |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 53.8 (9.5) | 54.3 (11.3) | 47.8 (8.0) | 46.2 (7.1) | 3.1 (–0.6, 6.8) | |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 144.3 (24.4) | 137.1 (27.5) | 128.7 (33.8) | 126.7 (33.1) | 5.3 (–9.1, 19.6) | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 146.8 (44.3) | 151.6 (84.6) | 135.1 (72.8) | 113.9 (62.1) | 26.0 (–31.5, 83.5) | |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.55 (1.17) | 5.21 (0.79)** | 6.18 (1.17) | 5.87 (1.17)* | 1.03 (0.57, 1.49)**** | |

| Adiponectin (µg/ml) | 5.76 (2.07) | 6.18 (2.06)* | 5.51 (3.18) | 5.35 (3.00) | 0.59 (0.10, 1.07)*** | |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 31.98 (22.63) | 25.09 (14.18)* | 30.20 (17.30) | 31.46 (19.14) | 8.15 (1.56, 14.7)*** | |

| Other laboratory variables | ||||||

| hsCRP (mg/dl) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.28) | 0.16 (0.12) | 0.12 (0.09) | 0.14 (–0.04, 0.33) | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 14.4 (2.4) | 15.4 (3.8) | 13.2 (5.1) | 12.8 (2.8) | 1.34 (–1.83, 4.51) | |

| Cr (mg/dl) | 0.71 (0.18) | 0.69 (0.19) | 0.67 (0.16) | 0.67 (0.17) | 0.00 (–0.04, 0.05) | |

| Estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 86.7 (20.4) | 87.9 (20.5) | 100.1 (20.9) | 100.6 (20.4) | 0.9 (–6.1, 7.9) | |

| HT (%) | 45.1 (3.0) | 47.5 (2.8)** | 46.3 (4.8) | 44.8 (5.5) | 3.9 (2.4, 5.4)**** | |

| RBC (×104/µl) | 493 (26) | 518 (26)** | 516 (66) | 500 (72)* | 40 (25, 56)**** | |

| Hb (g/dl) | 14.9 (1.1) | 15.6 (1.1)** | 15.5 (1.8) | 14.8 (1.9)* | 1.4 (0.9, 1.8)**** | |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 246 (48) | 248 (50) | 222 (62) | 220 (76) | 8.85 (–21.02, 38.72) | |

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. *p<0.05 vs baseline; **p<0.01 vs baseline; ***p<0.05 vs teneligliptin; ****p<0.01 vs teneligliptin.

Changes in metabolic laboratory variables

In both the dapagliflozin and teneligliptin groups, HbA1c was significantly decreased from the baseline values of 5.90 ± 0.36% and 5.82 ± 0.23%, respectively, to 5.76 ± 0.24% (p = 0.02) and 5.66 ± 0.18% (p = 0.03), respectively, at post-treatment. In contrast, there were no significant changes in FPG, insulin, or HOMA-IR, nor in concentrations of HDL-C, LDL-C, or triglycerides at post-treatment as compared with the baseline values in either group. Serum uric acid concentrations in the two groups were significantly decreased from 6.55 ± 1.17 mg/dl and 6.18 ± 1.17 mg/dl, respectively, to 5.21 ± 0.79% (p<0.01) and 5.87 ± 1.17% (p = 0.02), respectively, after treatment. In the dapagliflozin group alone, serum adiponectin concentration was significantly increased from 5.76 ± 2.07 µg/ml to 6.18 ± 2.06 µg/ml (p = 0.02), while serum leptin concentration in those patients was significantly decreased from 31.98 ± 22.63 ng/dl to 25.09 ± 14.18 ng/dl (p = 0.04) at post-treatment (Table 2).

Changes in other laboratory variables

There were no significant changes in hsCRP, BUN, Cr, or estimated GFR in either of the groups. In the dapagliflozin group, HT, RBC, and Hb were significantly increased from the baseline values of 45.1 ± 3.0%, 493 ± 26 × 104/µl, and 14.9 ± 1.1 g/dl, respectively, to 47.5 ± 2.8% (p<0.01), 518 ± 26 × 104/µl (p<0.01), and 15.6 ± 1.1 g/dl (p<0.01), respectively, at post-treatment. In the teneligliptin group, RBC and Hb showed significant decreases from 516 ± 66 × 104/µl and 15.5 ± 1.8 g/dl, respectively, to 500 ± 72 × 104/µl (p = 0.04), and 14.8 ± 1.9 g/dl (p = 0.01), respectively (Table 2).

Changes in body compositions

In the dapagliflozin group, body weight and BMI were significantly decreased after treatment [body weight: 76.5 ± 20.7 kg at baseline to 75.2 ± 20.9 kg at post-treatment, p = 0.02], while there were no significant changes in waist circumference, body fat mass, percent body fat, or percent skeletal muscle (Table 3). In the dapagliflozin group, significant decreases were seen at post-treatment for total body water (37.9 ± 11.0 to 37.2 ± 11.1 L, p = 0.02), protein (10.2 ± 3.1 to 10.0 ± 3.1 kg, p = 0.02), and mineral (3.48 ± 1.04 to 3.42 ± 1.03 kg, p = 0.01) levels, while there was no significant change in body fat mass. There were no significant changes in body composition factors seen in the teneligliptin group.

Table 3.

Changes in body compositions, blood pressure and hand grip strength after 12 weeks of treatment with dapagliflozin vs teneligliptin

| Dapagliptin group (n = 12) |

Teneligliptin group (n = 10) |

Difference (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-treatment | Baseline | Post-treatment | |||

| Body compositions | ||||||

| Body weight (kg) | 76.5 (20.7) | 75.2 (20.9)* | 78.4 (15.1) | 78.4 (15.0) | 1.4 (–0.0, 2.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 (4.3) | 27.4 (4.3)* | 28.7 (4.4) | 28.7 (4.5) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.1)*** | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 95.0 (10.7) | 94.3 (10.7) | 94.9 (9.6) | 95.2 (10.6) | 1.0 (–0.4, 2.4) | |

| Total body water (L) | 37.9 (11.0) | 37.2 (11.1)* | 37.4 (7.5) | 37.5 (7.6) | 0.74 (0.03, 1.45)*** | |

| Protein (kg) | 10.2 (3.1) | 10.0 (3.1)* | 9.8 (2.2) | 9.8 (2.2) | 0.19 (–0.01, 0.39) | |

| Mineral (kg) | 3.48 (1.04) | 3.42 (1.03)** | 3.45 (0.70) | 3.44 (0.71) | 0.05 (–0.01, 0.10) | |

| Body fat mass (kg) | 24.9 (8.1) | 24.5 (8.2) | 28.0 (8.8) | 28.2 (8.9) | 0.6 (–0.4, 1.6) | |

| Percent body fat (%) | 32.8 (7.2) | 32.8 (7.4) | 35.2 (6.0) | 35.3 (6.2) | 0.1 (–0.7, 1.0) | |

| Skeletal muscle mass (kg) | 28.7 (9.2) | 28.3 (9.2)* | 28.4 (6.3) | 28.4 (6.3) | 0.4 (–0.1, 1.0) | |

| Percent skeletal muscle (%) | 37.3 (4.8) | 37.3 (4.9) | 36.0 (3.8) | 36.0 (3.9) | 0.1 (–0.3, 0.6) | |

| Blood pressure | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126.1 (10.7) | 121.8 (8.6) | 121.8 (10.4) | 118.7 (8.6) | 1.2 (–5.2, 7.7) | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76.2 (7.1) | 74.7 (9.2) | 73.6 (3.8) | 71.8 (4.3) | 1.1 (–3.3, 5.6) | |

| Hand grip strength | ||||||

| Right hand grip strength (kg) | 35.8 (14.1) | 37.5 (13.2)* | 36.8 (9.6) | 38.1 (15.8) | 0.4 (–2.7, 3.4) | |

| Left hand grip strength (kg) | 32.9 (14.0) | 33.8 (12.5) | 33.9 (13.0) | 35.0 (13.7) | 0.3 (–2.0, 2.5) | |

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD; *p<0.05 vs baseline; **p<0.01 vs baseline; ***p<0.05 vs teneligliptin.

Correlations between changes in body weight and body composition factors in dapagliflozin group

In the present study, a significant decrease in body weight was found only in the dapagliflozin group. In this regard, we investigated which body composition factors were associated with decreased body weight in those patients. Since the output values of the InBody720 include total body water, protein, mineral, and body fat mass, with the sum of these values used as body weight, those 4 factors were subjected to the Spearman’s correlation test (Table 4). Change in body weight was found to be positively correlated with changes in total body water (r = 0.82, p<0.01), protein (r = 0.67, p = 0.02), mineral (r = 0.63, p = 0.03), and body fat mass (r = 0.78, p<0.01) levels. Furthermore, the multiple regression analysis showed that changes in total body water (PRC = 1.11, p<0.01) and body fat mass (PRC = 1.04, p<0.01) were significantly related to change in body weight in the dapagliflozin group.

Table 4.

Association of change in body weight with changes in body composition factors in dapagliflozin group

| Variables | r | PRC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Total body water (L) | 0.82* | 1.11* (0.86, 1.37) |

| Protein (kg) | 0.67** | 0.87 (–0.11, 1.84) |

| Mineral (kg) | 0.63** | –0.46 (–1.67, 0.75) |

| Body fat mass (kg) | 0.78* | 1.04* (0.97, 1.10) |

r, Speaman’s rank correlation coefficient; PRC, partial regression coefficient. *p<0.01, **p<0.05.

Changes in blood pressure and hand grip strength

There were no significant changes in blood pressure in either group. Right hand grip strength was significantly increased in the dapagliflozin group from 35.8 ± 14.1 kg to 37.5 ± 13.2 kg (p = 0.02) at post-treatment. In the teneligliptin group, there was no significant change in hand grip strength seen at post-treatment (Table 3).

Discussion

This single center double-blind randomized prospective study was performed to investigate the efficacy of SGLT2i and DPP4i in NAFLD patients without T2DM. Both dapagliflozin and teneligliptin administrations led to a significantly decreased serum ALT level when separately administered to NAFLD patients without T2DM for 12 weeks. Multiple regression analysis results showed that the decrease in body weight in patients with dapagliflozin administration was significantly related to changes in total body water and body fat mass.

The present results indicate that ALT reduction was accompanied by a reduction in HbA1c level in both groups. Glucose monitoring was performed using the FreeStyle Libre Flash continuous glucose monitoring system (FSL-CGM, Abbot Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA) for a total of 14 days, 7 days before and after starting administration of the drug. The FSL-CGM system automatically measures glucose every minute for up to 14 days, with clinical accuracy of the numerical readings reported to be 11.4% as compared to measurements obtained with a glucometer.(39) For the present cohort, glucose monitoring with the FSL-CGM system was successful in 10 patients in the dapagliflozin group and 8 in the teneligliptin group. The percentage of time when glucose concentration was less than 70 mg/dl before (dapagliflozin group 1.7 ± 2.6%, teneligliptin group 7.1 ± 7.4%) and after (1.6 ± 2.2%, 3.8 ± 3.9%, respectively) administration of the respective drug did not show a significant change, though the percentage of time when glucose concentration exceeded 140 mg/dl showed a decrease from 12.2 ± 8.1% to 6.7 ± 3.6% in the dapagliflozin group (p = 0.02) and from 7.3 ± 6.3% to 3.9 ± 5.4% in the teneligliptin group (p = 0.04). These results suggest that both dapagliflozin and teneligliptin improve glucose metabolism and HbA1c levels without causing hypoglycemia when given to NAFLD patients without T2DM.

In the present cohort, administration of dapagliflozin or teneligliptin decreased the ferritin concentration in serum along with a reduction in ALT level. Some previous studies,(40,41) but not all have found that the serum ferritin concentration in NAFLD patients is positively correlated with increasing hepatic fibrosis.(42–44) In another, results obtained with an experimental rat model of chronic steatohepatitis demonstrated that iron increases hepatocyte apoptosis and contributes to development of fibrosis both directly and indirectly via induction of TGF-β1 production by hepatocytes and macrophage.(45) Although the mechanism underlying elevation of serum ferritin in NAFLD is unknown, administration of alogliptin, a DPP4i, has been reported to reduce serum ferritin level and may prevent NAFLD progression in patients with T2DM.(46)

But another study found that serum ALT levels were not reduced even when the ferritin level in NAFLD patients was decreased by a phlebotomy.(47) Therefore, it will be necessary to perform an additional investigation in the future to determine whether a decreased level of ferritin is actually related to a decrease in serum ALT level and improvement of hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD patients.

Relationships of high serum uric acid with the risk of NAFLD,(48,49) cardiovascular disease,(50) and chronic kidney disease development have been reported.(51) SGLT2i administration lowers the serum uric acid concentration by increasing renal uric acid elimination.(52) Sitagliptin, a DPP4i, was reported to protect hepatic triglyceride accumulation by suppression of uric acid production via an adenosine deaminase/xanthine oxidase/uric acid-dependent pathway in an animal model.(53) In the present study, administration of dapagliflozin or teneligliptin lowered the serum uric acid level in NAFLD patients without T2DM, and we speculated that this effect will contribute to not only improve NAFLD, but also prevent cardiovascular and chronic kidney diseases.

Results of multiple regression analysis for the dapagliflozin group showed that changes in total body water and body fat mass were significantly related with changes in body weight. We also noted that the adiponectin concentration in serum was increased and that of leptin was decreased by administration of dapagliflozin. A previous meta-analysis showed that NAFLD patients had lower levels of adiponectin in serum as compared with control subjects and the results also indicated that hypoadiponectinemia may play an important pathophysiological role in progression from NAFL to NASH.(54) In a previous study, obese NAFLD patients were reported to have lower adiponectin and higher leptin concentrations as compared with lean controls,(55) while another showed that serum leptin and leptin resistance were positively correlated with hepatic steatosis in T2DM patients.(56) Furthermore, results of another meta-analysis investigation indicated that SGLT2i treatment in T2DM patients might contribute to beneficial effects toward metabolic homeostasis by decreasing leptin and increasing adiponectin levels.(57) Findings obtained in the present study suggest that administration of dapagliflozin to NAFLD patients without T2DM had the same effects noted in that meta-analysis report.

In the dapagliflozin group, skeletal muscle mass was significantly decreased after 12 weeks as compared to the baseline, whereas percent skeletal muscle did not change and hand grip strength was significantly increased, which might indicate improved skeletal muscle quality. Although the mechanism of hand grip strength increase by SGLT2i treatment is unclear, a previous study suggested that this effect is associated with not only improved chronic inflammation and adipokine balance, but also reduced interstitial edema and improved mitochondrial function, microcirculation, and peripheral nerve function.(58) SGLT2i has also been reported to suppress muscle atrophy in type 2 diabetic db/db mice.(59)

We also evaluated the safety profiles of dapagliflozin and teneligliptin in terms of general laboratory variables including hypoglycemia, but found no clinically significant changes in any of those variables in the present cohort. We speculated that the slight increase in hematocrit in the dapagliflozin group was not only a result of decreased total body water, but also reflected an increase in red blood cells, because no changes in BUN, Cr, or estimated GFR were observed. As for the teneligliptin group, while RBC and Hb were decreased, hematocrit did not change. These findings suggest that neither dapagliflozin nor teneligliptin had any negative effects on clinically relevant laboratory variables, though the patient groups were relatively small.

Limitations of this study include its single center design, short treatment period, and low number of patients. Our results showing ALT reduction less than 30% and body weight reduction less than 10% suggest that 12-week dapagliflozin or teneligliptin therapy given to an NAFLD patient without T2DM may not be adequate to improve hepatic histology including fibrosis.(7,8) Thus, we consider that lifestyle intervention in addition to pharmacotherapy is necessary to improve the histologic features of NAFLD patients without T2DM. Additional large-scale multi-center studies are needed to validate the efficacy of dapagliflozin and teneligliptin for treatment of NAFLD patients without T2DM.

In conclusion, this single center double-blind randomized prospective study showed that dapagliflozin and teneligliptin administered separately for 12 weeks to NAFLD patients without T2DM significantly decreased serum ALT levels. Nevertheless, a longer-term larger study is needed to verify these results, and confirm the efficacy of dapagliflozin or teneligliptin for treating this patient population.

Author Contributions

HT conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. SI contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. NI, KN, and SS contributed to the study concept and design. TY, MK, SK, and AO contributed to the acquisition of data. TM, NO, and KK contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no sources of funding, grant support and financial disclosure of this study.

References

- 1.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016; 64: 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eguchi Y, Hyogo H, Ono M, et al.; JSG-NAFLD. Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2009 to 2010 in Japan: a multicenter large retrospective study. J Gastroenterol 2012; 47: 586–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 1413–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafiq N, Bai C, Fang Y, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekstedt M, Hagström H, Nasr P, et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology 2015; 61: 1547–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seko Y, Sumida Y, Tanaka S, et al. Serum alanine aminotransferase predicts the histological course of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in Japanese patients. Hepatol Res 2014; 45: E53–E61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 367–378.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sberna AL, Bouillet B, Rouland A, et al. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) clinical practice recommendations for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: evaluation of their application in people with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2018; 35: 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumida Y, Yoneda M. Current and future pharmacological therapies for NAFLD/NASH. J Gastroenterol 2018; 53: 362–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drucker DJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition and the treatment of type 2 diabetes: preclinical biology and mechanisms of action. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1335–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwasaki T, Yoneda M, Inamori M, et al. Sitagliptin as a novel treatment agent for non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hepatogastroenterology 2011; 58: 2103–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yilmaz Y, Yonal O, Deyneli O, Celikel CA, Kalayci C, Duman DG. Effects of sitagliptin in diabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2012; 75: 240–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arase Y, Kawamura Y, Seko Y, et al. Efficacy and safety in sitagliptin therapy for diabetes complicated by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Res 2013; 43: 1163–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuhara T, Hyogo H, Ochi H, et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hepatogastroenterology 2014; 61: 323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui J, Philo L, Nguyen P, et al. Sitagliptin vs. placebo for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol 2016; 65: 369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joy TR, McKenzie CA, Tirona RG, et al. Sitagliptin in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain M, Majeed Babar MZ, Hussain MS, Akhtar L. Vildagliptin ameliorates biochemical, metabolic and fatty changes associated with non alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pak J Med Sci 2016; 32: 1396–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalra S. Sodium glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: a review of their basic and clinical pharmacology. Diabetes Ther 2014; 5: 355–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson JW, Lundkvist P, Jansson PA, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin and n-3 carboxylic acids on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in people with type 2 diabetes: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia 2018; 61: 1923–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuchay MS, Krishan S, Mishra SK, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on liver fat in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial (E-LIFT trial). Diabetes Care 2018; 41: 1801–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobita H, Sato S, Miyake T, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Effects of dapagliflozin on body composition and liver tests in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective, open-label, uncontrolled study. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2017; 87: 13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue M, Hayashi A, Taguchi T, et al. Effects of canagliflozin on body composition and hepatic fat content in type 2 diabetes patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Diabetes Investig 2019; 10: 1004–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itani T, Ishihara T. Efficacy of canagliflozin against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective cohort study. Obes Sci Pract 2018; 4: 477–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito D, Shimizu S, Inoue K, et al. Comparison of ipragliflozin and pioglitazone effects on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, 24-week, open-label, active-controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2017; 40: 1364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibuya T, Fushimi N, Kawai M, et al. Luseogliflozin improves liver fat deposition compared to metformin in type 2 diabetes patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective randomized controlled pilot study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018; 20: 438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyake T, Yoshida S, Furukawa S, et al. Ipragliflozin ameliorates liver damage in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Open Med (Wars) 2018; 13: 402–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabuchi H, Maegawa H, Tobe K, Nakamura I, Uno S. Effect of ipragliflozin on liver function in Japanese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a subgroup analysis of the STELLA-LONG TERM study (3-month interim results). Endocr J 2019; 66: 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohki T, Isogawa A, Toda N, Tagawa K. Effectiveness of Ipragliflozin, a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, as a second-line treatment for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who do not respond to incretin-based therapies including glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Clin Drug Investig 2016; 36: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sumida Y, Murotani K, Saito M, et al. Effect of luseogliflozin on hepatic fat content in type 2 diabetes patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective, single-arm trial (LEAD trial). Hepatol Res 2019; 49: 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kusunoki M, Natsume Y, Sato D, et al. Luseogliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, alleviates hepatic impairment in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2016; 66: 603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Itoh Y, et al. The severity of ultrasonographic findings in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease reflects the metabolic syndrome and visceral fat accumulation. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2708–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998; 15: 539–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al.; International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; Hational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009; 120: 1640–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honda T, Chen S, Yonemoto K, et al. Sedentary bout durations and metabolic syndrome among working adults: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizuno N, Seko Y, Kataoka S, et al. Increase in the skeletal muscle mass to body fat mass ratio predicts the decline in transaminase in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol 2019; 54: 160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1487–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2010; 59: 1265–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bailey T, Bode BW, Christiansen MP, Klaff LJ, Alva S. The performance and usability of a factory-calibrated flash glucose monitoring system. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015; 17: 787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manousou P, Kalambokis G, Grillo F, et al. Serum ferritin is a discriminant marker for both fibrosis and inflammation in histologically proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Liver Int 2011; 31: 730–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kowdley KV, Belt P, Wilson LAet al.; NASH Clinical Research Network. Serum ferritin is an independent predictor of histologic severity and advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2012; 55: 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angulo P, George J, Day CP, et al. Serum ferritin levels lack diagnostic accuracy for liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 1163–1169.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoneda M, Thomas E, Sumida Y, et al. Clinical usage of serum ferritin to assess liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: proceed with caution. Hepatol Res 2014; 44: E499–E502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buzzetti E, Petta S, Manuguerra R, et al. Evaluating the association of serum ferritin and hepatic iron with disease severity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 2019; 39: 1325–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.George J, Pera N, Phung N, Leclercq I, Yun Hou J, Farrell G. Lipid peroxidation, stellate cell activation and hepatic fibrogenesis in a rat model of chronic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 2003; 39: 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mashitani T, Noguchi R, Okura Y, et al. Efficacy of alogliptin in preventing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes. Biomed Rep 2016; 4: 183–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams LA, Crawford DH, Stuart K, et al. The impact of phlebotomy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology 2015; 61: 1555–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Y, Wei F, Fan Y. High serum uric acid and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biochem 2016; 49: 636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Darmawan G, Hamijoyo L, Hasan I. Association between serum uric acid and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Acta Med Indones 2017; 49: 136–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu AH, Gladden JD, Ahmed M, Ahmed A, Filippatos G. Relation of serum uric acid to cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol 2016; 213: 4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, Yu Y, Li X, et al. Serum uric acid levels and decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2018; 34: e3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chino Y, Samukawa Y, Sakai S, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor lowers serum uric acid through alteration of uric acid transport activity in renal tubule by increased glycosuria. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2014; 35: 391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Omolekulo TE, Michael OS, Olatunji LA. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition protects the liver of insulin-resistant female rats against triglyceride accumulation by suppressing uric acid. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 110: 869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polyzos SA, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Zavos C, Kountouras J. Serum total adiponectin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2011; 60: 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stefan N, Bunt JC, Salbe AD, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Tataranni PA. Plasma adiponectin concentrations in children: relationships with obesity and insulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 4652–4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cernea S, Roiban AL, Both E, Huţanu A. Serum leptin and leptin resistance correlations with NAFLD in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2018; 34: e3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu P, Wen W, Li J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effect of SGLT2 inhibitor on blood leptin and adiponectin level in patients with type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 2019; 51: 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sano M, Meguro S, Kawai T, Suzuki Y. Increased grip strength with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2. J Diabetes 2016; 8: 736–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Osaka T, Fukuda T, Hamaguchi M, Fukui M. The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor luseogliflozin can suppress muscle atrophy in Db/Db mice by suppressing the expression of foxo1. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2019; 65: 23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]