Abstract

Aim

Less empirical attention has been paid to the positive relationship between voice behaviour and voice speaker development, such as self‐leadership. The present study explores the relationship among nurses’ voice, perceived insider status and self‐leadership.

Method

This study was based on time‐lagged survey data collected from 608 frontline nurses. jamovi and PROCESS macro were used for analysis.

Results

Promotive voice and prohibitive voice were positively associated with self‐leadership. Perceived inside status mediated the relationship between promotive voice/prohibitive voice and self‐leadership. Prohibitive voice was more strongly related to self‐leadership than promotive voice.

Conclusions

When nurses dare to voice, nurses’ self‐leadership can be enhanced through perceived insider status improving, especially for nurses who dare to prohibitive voice.

Implications for nursing management

Nurse managers should protect the privacy of voice, continually provide feedback on voice and set up special encouragement for prohibitive voice.

Keywords: perceived inner status, prohibitive voice, promotive voice, self‐leadership

1. INTRODUCTION

The value of nurses to the hospital is not only reflected in the labour force they have, but also in their ability and courage to generate and speak up innovative ideas (Morrison, 2011). Employee voice behaviour refers to “the expression of constructive opinions, concerns, or ideas about work‐related issues” (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001, p. 327). Liang et al. (2012) divided voice behaviour into promotive voice and prohibitive voice. Promotive voice refers to putting forward new ideas and methods to improve the efficiency of enterprises. Prohibitive voice refers to expressing the inhibitive viewpoint and the harmful problem that hinders the efficiency of the organization. Studies have largely found employee voice behaviour was positively related to organizational outcomes (Morrison, 2011). For example, voice behaviour can establish and stabilize employment relationships, improve employees' work–life quality and job satisfaction and promote organizational learning and innovation (Morrison, 2011). However, despite supervisors encouraging employees' voice, subordinates may still decide to keep silent when they have new ideas (Morrison, 2014).

In China context, the voice speaker is good at the visualization of success and increasing their control over the organization through self‐talk, encouragement and punishment, which are all related to improving self‐leadership (Gong & Li, 2019). Besides, someone who proposes to improve the collective outcomes, even though they face risks, may be perceived by coworkers as altruistic and public‐oriented and gain the natural rewards of the organization such as the sense of competence and control. A means by which nurses help their hospitals to innovate and successfully adapt to dynamic environments is through “voice”—the expression of constructive opinions, concerns or ideas about work‐related issues. Indeed, nurses’ voice about improvements to or existing failures in the work process has been associated with positive organizational outcomes such as crisis prevention, improved work processes and innovation and team learning (Detert & Edmondson, 2011).

When choosing to keep silent or voice, the individual will engage in voice calculus, where they weight the expected benefits against risks (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). These risks are important to consider because research has found a negative relationship between voice behaviour and personal outcomes. Supervisors do not always respond positively to subordinates who voice their opinions (Howell et al., 2015). Employees who speak up may also consider the social results of voice. Because the changes brought by voice could make other coworkers feel embarrassed and bring more work, coworkers may blame the speaker (Dyne et al., 2003). The speaker faces real risks (Morrison, 2014), such as damage to their public image (perceived as complainers or troublemakers), lower performance evaluation and job assignment adverseness (Chamberlin et al., 2017).

Previous studies emphasized the value of voice behaviour to organizations and the risks to the voice speaker, but less empirical attention has been paid to the value to the individual who speaks up to the organization (Chamberlin et al., 2017). The omission of the research may result in voice vacuum in the literature, even if organizations encourage employees to voice. Addressing this omission is important. There are theoretical reasons to expect leaders and coworkers could evaluate the speaker positively in ways that could benefit the voice speaker. First, voice behaviour benefits the organization (McClean et al., 2018). Although changes in the status quo may threaten some leaders (Burris, 2012), it is less likely to threaten coworkers, because the original intention of voice behaviour is to make the organization better. Secondly, voice is regarded as key to leadership (McClean et al., 2018). Therefore, the harder the subject of voice behaviour tries to address organizational development, the more this may improve their self‐regulation, self‐management and self‐leadership. Finally, studies from multiple fields have shown that people who actively participate in teams can achieve higher social status (McClean et al., 2018). People who are speaking up can be perceived as having higher insider status in the team because team members identify the speaker's ability and social skills (Kennedy et al., 2013).

Following the above idea, we infer that voice was positively and indirectly associated with self‐leadership via perceived inside status. Reviewing previous studies, scholars have analysed the influence mechanism of voice behaviour from different perspectives, both theoretically and empirically (Liang et al., 2012). However, after reviewing the literature, there are issues in need of further clarification.

First, the existing research on voice has focused mainly on the antecedents of voice and the relationship between voice and collective outcome (Liang et al., 2012), but empirical studies on the personal results of voice behaviour are sparse (Chamberlin et al., 2017). An employee who expresses new and useful ideas is viewed as being a conscientiousness and autonomous employee, and if the ideas that are expressed by speaker are put to use, this could result in the speaker have more self‐control and responsibility for the unit (Gilal et al., 2020). Self‐leadership is a process of self‐influence carried out by people for self‐guidance and self‐motivation (Manz, 2011). Research has found a positive correlation between internal locus of control and self‐leadership (Manz, 2011). Thus, characteristic levels of voice may develop in units through a reinforcing cycle of attraction–selection–attrition that influence self‐leadership outcomes.

Second, there is still a debate about the potency and strength of promotive voice behaviour or prohibitive voice behaviour. Although studies have consistently found that both voice behaviours could promote task performance, each had a special relationship with organizational citizenship behaviour, innovation performance, safety performance and counterproductive work behaviour (Morrison, 2014). Previous research emphasized the positive association between promotive voice and the unit‐level outcomes, but prohibitive voice may have stronger positive relationship with the individual‐level outcome (Chamberlin et al., 2017). We believe that promotive voice and prohibitive voice behaviours have different relationship strength with the speaker's perceived insider status and self‐leadership.

Thirdly, previous studies on the influence mechanism of voice behaviour have mainly focused on the improvement of job satisfaction, the reduction in psychological pressure and procedural fairness (Ng & Feldman, 2012). However, prior research and theory do not always translate into practice. When the external organizational situation and leaders have solved the above issues, why are some subordinates still reticent to engage in voice? Further, even if some employees’ self‐esteem is not high, they still dare to engage in voice, even though they know that voice behaviour is risky, but they engage in voice due to having developed a strong sense of belonging and obligation for the organization. Previous research has not addressed these situations. Perceived insider status can address this gap. Perceived insider status is the degree to which an employee can perceive his or her insider identity and acceptance (Stamper & Masterson, 2002). Individuals with collectivist tendencies focus on the goals of their group (Hofstede & Bond, 1988). In this cultural context, whether employees' voice behaviour can promote their perception of the identity of "internal group members" will directly affect their self‐leadership.

The aim of this study was to analyse the association among nurses’ voice behaviour, perceived insider status and self‐leadership. In addition, we argue the positive relationship between promotive voice and self‐leadership is weaker than the positive relationship between prohibitive voice and self‐leadership. From a historical point of view, whether a historical figure like Wei Zheng (politician, thinker and historian in Tang Dynasty China, who was later called “a famous prime minister” in ancient China because he engaged in voice to speak truthfully and directly to assist Tang Taizong to jointly create the “Governance of Zhenguan Conception”) or another dares to speak truth to power, their voice can increase identity with the emperor, to increase its auxiliary dynasty with high sense of belonging, which in turn can improve the effectiveness of self‐management. So, can a similar process happen in the hospital? Do promotive voice and prohibitive voice improve the internal identity perception of nurses and then promote the improvement of self‐leadership? This is the core question this study seeks to answer.

1.1. Voice and self‐leadership

Self‐leadership strategies can be divided into three strategies, behavioural focus strategy, natural reward strategy and constructive thinking strategies (Houghton & Neck, 2002). Prior literature has shown that voice is associated with some dimensions of self‐leadership. Voice behaviour is a change‐oriented behaviour, and voice represents public orientation and a willingness to take others' risks (Houghton & Neck, 2002). Prior literature has shown that voice is associated with some dimensions of self‐leadership. Voice behaviour is a change‐oriented behaviour and voice represents public orientation and a willingness to take others' risks. Individuals need to master enough information about the organization and the work process, and then, they can voice suggestions for changing it. Thus, someone engaging in voice has a clear understanding of goal setting (Morrison, 2014). Previous studies have confirmed that people who dare to voice their opinions were considered more competent and confident (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). Cody and McGarry (2012) used student samples to find that individual autonomous voice can enhance self‐confidence. One possible explanation is that when there are many opportunities to express opinions, subordinates would gain a sense of fairness, value and control over their work. Thus, proactive/prohibitive voice behaviour may positively related to self‐leadership.

Second, from the perspective of the feedback loop, voice behaviour is an active behaviour, which can bring positive feedback to the subject (Morrison, 2014). Studies have shown that individuals can improve self‐leadership through a variety of proactive change behaviours, including doing things that demonstrate competence, acting selflessly on behalf of the team and improving individual value to the team in other ways (Houghton & Neck, 2002). The constructive nature of voice and the underlying intention to benefit the organization suggest that using voice may enhance the perceived value of an employee to the organization. As an instance of the promotive voice, the ideas that are conveyed by a speaker can result in innovations attributable to the unit. As an instance of the prohibitive voice, the behaviour may bring to light counterproductive behaviour among individuals in the speaker's unit (Chamberlin et al., 2017). Voice is a means through which individuals determine and shape their work environment. In return, supervisors and coworkers in the organization will provide material and information support to help voice speakers improve self‐leadership (Avery & Quiñones, 2002). We consider that proactive voice can address behaviour issues in ways that are dynamic (McClean et al., 2018). The sum of research highlights the importance of autonomy, personal control or influence in producing positive affective reactions in individuals. Voice behaviour about aspects of one's work role should lead to a better match between the demands of the job and one's talents, needs and values. Such matching is a key element of self‐leadership (Ng & Feldman, 2012).

Thirdly, promotive voice behaviour and prohibitive voice behaviour work through different mechanisms and differ in their effectiveness. Promotive voice calls for novel ideas to accomplish goals and perform work tasks and long‐term improvements and innovation (Qin et al., 2014). Central to the notion of promotive voice is the idea of enhancing organizational performance by doing new things with a future‐oriented outlook (Liang et al., 2012). Thus, promotive messages are often drawn up as expressions of “what could be” and are embedded with good intentions that are often readily interpreted as being positive. In contrast, prohibitive voice focuses on harmful or wrongful work practices or events that currently exist (Liang et al., 2012). Employees use prohibitive voice as a way of benefiting the organization by preventing negative consequences. Therefore, prohibitive messages are often framed as expressions of “what could not be” and generating attention to the status quo, actively highlighting problematic practices that misalign with the organization's values. Prohibitive voice is more effective than promotive voice because the process of generating creative ideas needs time and effort. In contrast, prohibitive voice focuses on stopping harm, especially in special work context where safety and counterproductive activities are consequential (Morrison, 2011). Employees engaging in prohibitive voice tend to be perceived as stricter in their self‐monitoring, self‐control and self‐voice than employees who engage in promotive voice (Morrison, 2014). Promotive voice thus has a weaker association with self‐leadership. These observations lead us to propose the following set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: There will be a positive relationship between proactive voice behaviour and self‐leadership.

Hypothesis 2: There will be a positive relationship between prohibitive voice behaviour and self‐leadership.

Hypothesis 3: The positive relationship between promotive voice and self‐leadership is weaker than the positive relationship between prohibitive voice and self‐leadership.

1.2. Voice and perceived insider status

Voice behaviour is an interpersonal communication behaviour, and communication among team members has been demonstrated to have an important impact on team performance (Burris, 2012; Van Swol et al., 2018). By presenting ideas and suggestions repeatedly, members share knowledge and expertise within the team (Chamberlin et al., 2017). Voice behaviour affects the insider's identity perception in many ways. Generating ideas formed by professional thinking underlies voice behaviour. Specialized and heterogeneous knowledge of individual members is exchanged within the team frequently. This information exchange can promote labelling members as having expertise in a specialized field. Thus, the member is perceived to provide diversified knowledge for the promotion of the team, and this improves the member's insider identity from their voice behaviour. Voice behaviour is built on the team psychological safety (Chamberlin et al., 2017). The speaker puts forward suggestions based on trust and positive expectations of voice behaviour results. Active voice helps in the formation of an open and trusting atmosphere (Howell et al., 2015). This atmosphere will further stimulate voice behaviour, thus forming a cycle of mutual promotion between voice behaviour, team identification and a sense of integration and psychological safety.

People define themselves by their group memberships and desire people they respect to join the team because individuals tend to choose members who can positively affect self‐identity (Chamberlin et al., 2017). Group members benefit by choosing capable people as collaborators because through the voice of these members, the group can gain sufficient resources and the trust of stakeholders and ensure the development of the team by thinking about the opportunities and challenges of organizational development (Morrison, 2011). As a result, team members will benefit from their collaborators and feel fully integrated. The speaker actively points out the problems and solutions in the team, which can help other members to understand the intention of the speaker and choose appropriate response methods accordingly. Therefore, voice behaviour helps members to achieve proper cooperation.

The longer the employees work for the organization, the deeper their understanding will become, which will generate a sense of integration into the organization and thus increase their identity as insiders (McClean et al., 2018). In addition, the more employees want to make suggestions for the organization, the more familiar they are with the procedures and codes of conduct within the organization and the more likely they have access to important people or information within the company (Liang et al., 2012). Therefore, they are most likely to acquire knowledge and experience belonging to "insiders," thus generating the perception of "insiders." Employees who get more rewards will think that they should work hard and contribute to the organization (McClean et al., 2018). Because of this cycle, the organization treats employees differently, so that employees have different perceptions of "insiders" and "outsiders." Thus, proactive/prohibitive voice behaviour may be positively related to perceived insider status. These observations lead us to propose the following set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4: There will be a positive relationship between proactive voice behaviour and perceived insider status.

Hypothesis 5: There will be a positive relationship between prohibitive voice behaviour and perceived insider status.

1.3. The mediating role of perceived insider status between voice and self‐leadership

When employees classify themselves as "insiders" of the organization, they will take the initiative to understand the role they play in the organization, adopt attitudes and behaviours that fit the insider role and fulfil the organization's norms. Previous studies have shown that employees with a higher awareness of their own insider identity would show more cooperative attitudes and behaviours with the organization (Li et al., 2014). Confidence and group participation are related to self‐leadership growth (Stamper & Masterson, 2002). When employees see themselves as an insider, they can communicate more easily with members due to their perceived responsibility and sense of duty. Employees can focus their actions directed by self‐reward and punishment (Li et al., 2014). Perceived insider status signals trust and recognition to someone engaging voice behaviour, and it is an important signal for the team to invest in someone engaging in voice. Once the employee receives these signals, the employee often goes above and beyond his or her responsibility, in the hope that the reciprocal responsibility will be realized in the exchange. Perceived insider status can help to meet employees' needs for social and emotional connection and forms a self‐cognition of citizenship (Stamper & Masterson, 2002). To avoid cognitive dissonance, people tend to behave in ways that are consistent with their perceptions. Therefore, the self‐cognition of citizenship generated by high‐level insider identity perception will affect employees' behaviours. It inclines employees to act in a manner consistent with their sense of citizenship, regarding it as their responsibility to maintain the effective functioning of the organization as a whole:

Hypothesis 6: There will be a positive relationship between perceived insider status and self‐leadership.

Given the importance of voice, employees who exhibit voice tend to get more recognition and high‐performance evaluations (Chamberlin et al., 2017). This perception will stimulate the utilitarian motivation of employees to use voice to actively obtain resources. In other words, employees will take action to accumulate resources. Employees with a high sense of insider identity will try their best to cultivate the resources value‐added and are more willing to put it into self‐leadership that is conducive to the operation of the organization (McClean et al., 2018). Research has shown that employees who were more willing to voice their opinions to the organization were more likely to bond with their team members. The closer the relationship between employees and the organization, the easier it is for them to regard themselves as "insiders" in the organization (Chamberlin et al., 2017). Thus, people construct self‐concepts through their interactions with others. Promotion not only brings the satisfaction of resources like power and status, but also makes employees feel recognized by the organization, and enhances the responsibility and obligation to the organization and the opportunity to improve themselves:

Hypothesis 7: Perceived insider status mediates the relationship between voice and self‐leadership.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This study was a time‐lagged survey design using a sample of 608 registered nurses of China. We sent surveys to participants at three time points and there were 3 months between the periods.

2.2. Data collection

With the agreement of the director of nursing of the hospital, all the questionnaires were completed during the nurses’ work hours. We obtained written informed consent before the survey. Participants completed the survey voluntarily and anonymously without any negative consequences. After signing and returning the consent form, each nurse was presented with the survey instrument by researchers. To match the 3‐wave questionnaire and ensure anonymity, each participant was required to write out the last six digits of the ID card. Using convenience sampling, the questionnaires were sent to nurses at 18 community hospital branch units and 15 general hospital units. The nurses were measured by layer cluster sampling. Depending on the principle of convenience sampling, 683 questionnaires were distributed, and 608 valid questionnaires were returned to researchers directly (an effective response rate of 89.02%).

2.3. Participants

According to the power analysis criteria (α = 0.05, β = 0.20, H1 p 2 = 0.1, H0 p 2 = 0), we needed a sample of more than 136. A total of 608 nurses completed the survey. Of the 608 nurses completing a valid survey, 75% (N = 456) were female and 25% (N = 152) were male. As for their age, because nurses are mostly young women in China, 34.2% (N = 208) were under the age of 25 years, 39.5% (N = 240) were 26–35 years of age and 26.3% (N = 160) were more than 36 years old. With regard to their organizational tenure, 26.97% (N = 164) had worked for less than 5 years, 36.02% (N = 219) for 6–15 years and 37.01% (N = 225) for more than 16 years. Concerning education, 84.05% (N = 511) held a bachelor's degree and below (junior college, technical secondary school, such as graduate from 2–3 years of college and technical secondary school). The demographic information is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variables | Attributes | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 152 | 25 |

| Female | 456 | 75 | |

| Age | Under 25 | 208 | 34.2 |

| 25 ~ 35 | 240 | 39.5 | |

| Above 36 | 160 | 26.3 | |

| Tenure | Under 5 | 164 | 26.97 |

| In | 6~15 | 219 | 36.02 |

| Hospital | Above 15 | 225 | 37.01 |

| Education | Below Bachelor | 511 | 84.05 |

| Above Bachelor | 97 | 15.95 | |

| Total | 608 | 100.0 | |

2.4. Variables

All items use a 7‐point Likert‐type scale from 1 (none at all)–7 (a great deal) for measurement. Promotive voice. We measured the promotive voice using Liang et al.’s (2012) scale (Time 1). We asked each sample to rate the frequency with which they voice promotively by using three items (e.g. “I proactively suggest new projects which are beneficial to the work unit.”). The criteria of internal consistency of Cronbach's α coefficient are above 0.70. The fit indices of this scale were χ 2/df = 1.12, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, CR = 0.96 and AVE = 0.82. Hence, this is an appropriate survey to measure promotive voice.

Prohibitive voice. We measured the prohibitive voice using Liang et al.’s (2012) scale (Time 1). We asked each sample to rate the frequency with which they voice prohibitively using three items each (e.g. “I speak up honestly with problems that might cause serious loss to the work unit, even when/though dissenting opinions exist.”). Cronbach's α for the prohibitive voice was 0.89. The fit indices of this scale were χ 2/df = 2.49, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.88, CR = 0.92 and AVE = 0.70.

Perceived insider status. To measure perceived insider status, a 6‐item scale by Stamper and Masterson (2002) was used (Time 2) (e.g. “I feel very much a part of my work organization.”). Cronbach's α for perceived insider status was 0.78. The fit indices of this scale were χ 2/df = 2.2, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, CR = 0.95 and AVE = 0.76.

Self‐leadership. To measure status, we adapted items from Houghton and Neck (2002) (Time 3). This scale consists of 35 items (e.g. “when I do an assignment especially well, I like to treat myself to something or activity I especially enjoy.”). Cronbach's α for perceived insider status was 0.94. The fit indices of this scale were χ 2/df = 3.8, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, CR = 0.90 and AVE = 0.83.

2.5. Data analysis and availability

jamovi 1.2.2 and PROCESS macro 3.3 were used for statistical procedures. Jamovi was used for demographic distribution analysis, descriptive analysis, validity and reliability of the measurement analysis, correlation analysis and regression analysis. PROCESS macro 3.3 was used to confirm the relationships between variables and significance by bootstrapping (Hayes, 2013). We used the procedure to test the difference between 2 beta coefficients (Cumming & Finch, 2005). There is a possibility of CMB (common method bias) when measuring all constructs in the same survey. This study adopted a single factor test to clear the CMB issue. When conducted principal component analysis (non‐rotation) with all factor fixed as 1 component, the factor with the most massive explanatory power was not greater than half of the total variance (39.87%), confirming that there was no problem. The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

2.6. Ethical considerations

This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of Liaocheng University (17_7_14).

3. RESULTS

Table 2 presents the standard deviations, means and correlations. Promotive voice (r = .55, p < .01) and prohibitive voice (r = .43, p < .01) were significantly correlated with self‐leadership. Promotive voice (r = .23, p < .01) and prohibitive voice (r = .25, p < .01) were positively correlated with perceived insider status. Furthermore, perceived insider status was positively correlated with self‐leadership (r = .36, p < .01).

TABLE 2.

Means, standard deviations and correlations of all measures

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Promotive voice | 3.61 | 0.97 | — | |||

| 2. Prohibitive voice | 3.44 | 0.87 | 0.47** | — | ||

| 3. Perceived insider status | 3.02 | 0.58 | 0.23** | 0.25** | — | |

| 4. Self‐leadership | 3.44 | 0.71 | 0.55** | 0.43** | 0.36** | — |

| 5. Gender | 1.75 | 0.43 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.13* |

| 6. Age | 3.70 | 1.15 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.04 |

| 7. Job tenure | 4.74 | 1.67 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 8. Education | 1.43 | 0.49 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.16* | 0.05 |

N = 608; *p < .05, **p < .01.

To examine whether promotive voice and prohibitive voice was associated with nurses’ self‐leadership via perceived insider status, we adopted the PROCESS analysis that was conducted to verify the effect size on direct and indirect relationships simultaneously. By default, 5,000 re‐sampling of the percentile bootstrapping method is used to estimate the parameters. The absence of 0 in the 95% confidence interval identifies the statistical significance (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical regression results about mediation effect

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived insider status as dependent variable | Self‐leadership as dependent variable | |||||

| Constant | 2.24 | 2.31 | 1.28 | 0.60 | 1.26 | 0.62 |

| Promotive voice | 0.15** | 0.42** | 0.37** | |||

| Prohibitive voice | 0.16** | 0.53** | 0.48** | |||

| Perceived insider status | 0.30** | 0.28** | ||||

| Gender | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.28** | 0.31** | 0.23* | 0.26* |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.14* | −0.16* |

| Job tenure | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10* | 0.11* |

| Education | 0.25* | 0.22* | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 |

| R2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.7 |

| △R2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| F | 3.18 | 3.14 | 15.61** | 16.38** | 22.96** | 22.98** |

N = 608; *p < .05, **p < .01.

As shown in Table 3, with gender, age, job tenure and education used as control variables, promotive voice (β = 0.42; p < .01; Model 3) and prohibitive voice (β = 0.53; p < .01; Model 5) were significantly associated with self‐leadership, in support of Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. With gender, age, job tenure and education used as control variables, promotive voice (β = 0.15; p < .01; Model 1) and prohibitive voice (β = 0.16; p < .01; Model 2) were significantly associated with perceived insider status.

When perceived insider status was present, the relationship between promotive voice and self‐leadership became less‐significant (β = 0.37; p < .01; Model 4), but perceived insider status (β = 0.30; p < .01; Model 4) was significantly associated with self‐leadership. The effect size of an indirect relationship between promotive voice and self‐leadership via perceived insider status was confirmed (indirect effect = 0.05; p < .01), with a bootstrap 95% confidence interval of 0.01 to 0.09 that did not contain 0.

When perceived insider status was present, the relationship between prohibitive voice and self‐leadership became less‐significant (β = 0.48; p < .01; Model 6), but perceived insider status (β = 0.28; p < .01; Model 6) was significantly associated with self‐leadership. The effect size of an indirect relationship between prohibitive voice and self‐leadership via perceived insider status was confirmed (indirect effect = 0.06; p < .01), with a bootstrap 95% confidence interval of 0.01 to 0.11 that did not contain 0.

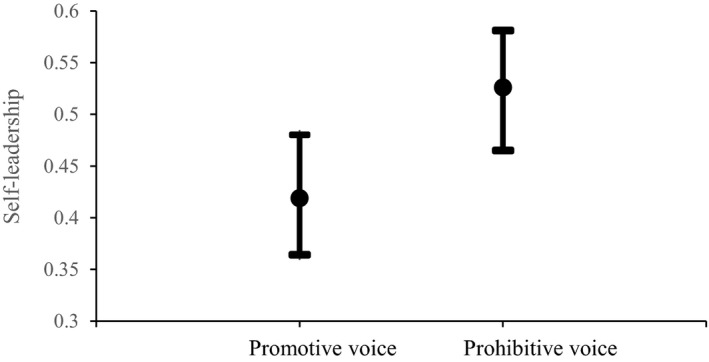

As can be observed in Figure 1, there appeared to be approximately 50% overlap in the confidence intervals. To assess the hypothesis more precisely, we used 3 decimal places here. Half of the average of the overlapping confidence intervals was calculated (0.031) and added to the prohibitive voice beta weight lower bound estimate (0.465) which yielded 0.496. As the promotive voice, upper bound estimate of 0.481 did not exceed the value of 0.496. The positive relationship between prohibitive voice and self‐leadership standardized beta weight was considered significantly weaker than the promotive voice beta weight.

FIGURE 1.

Means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for a two‐independent example

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Interpreting the findings

In this study, we examined how different types of voice were associated with individual nurses’ perceived insider status and self‐leadership. The study showed that, compared with promotive voice behaviour, prohibitive voice behaviour was more likely to improve self‐leadership and voice behaviour indirectly affected self‐leadership through perceived insider status. These findings have theoretical contributions to the literature on voice and self‐leadership which we discuss next.

The main contribution of this study is that it expands the theoretical understanding of voice behaviour by exploring voice from the perspective of the speaker. This change of perspective highlights how voice is a potential way for the group insiders to improve self‐leadership. This fills a gap given the limited research on the personal outcomes of voice. Prior research has almost entirely focused on external performance evaluation and voice behaviour recognition (Howell et al., 2015). While external perceptions are critical to success in an organization, individual growth is an internal social process and depends on the recognition of self‐leadership. Without considering the individual's views on voice behaviour, it cannot fully show people's weighing the advantages and disadvantages of voice behaviour when deciding whether to conduct voice. However, from the perspective of the speaker, previous studies have paid more attention to the risks of voice speaker. Such research results are difficult to explain since if voice behaviour is not beneficial, then what are the motives of voice speaker? Why are people willing to take the risk of continuing to voice their opinions when it is not good for them? We found that from the point of view of voice speaker, voice behaviour has a positive impact on the speaker. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Liang et al., 2012). People who presume to voice are more likely to engage in managing one's own career actively (McClean et al., 2018). This research confirms the general proposition that prior research treats people as passive, emphasizing organizational context influences on behaviour. In contrast, researchers argued that people could actively shape environments and thus create favourable outcomes for themselves (Chamberlin et al., 2017).

We also combine voice behaviour research with the research on insider perception and self‐leadership, providing important conditions for the long‐held belief that voice behaviour in groups is associated with status and leadership (McClean et al., 2018). By taking the initiative to learn about the organization and other relevant personnel, employees can find opportunities and problems in the development of the organization. Especially, new employees can reduce uncertainty, understand the new environment better and increase psychological safety. Through searching for information, employees can improve their job competence and cultural integration (Howell et al., 2015). Employees can take the initiative to make suggestions and provide information for leaders and organizations. Providing valuable information will make new employees more identify themselves with the organization, especially their role in the new organization. Employees provide information or innovative ideas to others not only prove their ability and improve their status in the organization, but also bring their own innovation results, thus accelerating the process of socialization. Employees with a high desire for control are more likely to think positively and to respond to information to boost their confidence and self‐efficacy. Compared with passive employees, employees who show an active image are more likely to be accepted and recognized by coworkers.

Our research also helps us to understand the results of promotive and prohibitive voice behaviour. Most prior empirical research has paid more attention to “promotive” aspects of voice, rather than the different effects of different voice, leading to inconsistent results (Liang et al., 2012). For example, empirical associations between voice and job performance have been inconsistent and there are conceptual reasons to think that the influence of voice may vary as a function of whether the voice is promotive or prohibitive. Researchers have considered that a promotive voice was positive in tone, and consequently, employees who engaged in promotive voice were likely to be recognized for their voice in the form of higher ratings of job performance (Liang et al., 2012). In contrast, prohibitive voice focused on the presence of risks and harmful situations, but the message may evoke defensive reactions, so research has found a negative relationship between voice and job performance. Although promotive voice can put forward constructive suggestions to improve the working process and improve the organizational capacity, it can also prevent the organization from being confronted with difficulties and avoid significant negative losses. Nevertheless, the effect of prohibitive voice does not seem to be positive in empirical studies (Chamberlin et al., 2017). In the current study, we established and tested the theory to demonstrate why promotive voice behaviour and prohibitive voice behaviour have different results for individuals and prohibitive voice behaviour is more conducive to the improvement of self‐leadership than promotive voice behaviour according prior researchers’ advocating (Chamberlin et al., 2017). Since the sample of this study focuses on nurses, professional reasons of nurses require nurses to avoid making mistakes and obtain safety performance as much as possible. Thus, nurses focus more on safety performance and counterproductive behaviour in terms of personal focus, so prohibitive voice behaviour has a greater effect.

4.2. Implications for nursing management

Although there are many good stories about voice and speaking truth to power in Chinese history, such as Wei Zheng's frank words and Tang Taizong's kindness, employees in Chinese organizations often ignore the problems existing in the organization. The doctrine of the mean, relationship, face and favour is all cultural characteristics in China, which have an important influence on the Chinese people's thinking and behaviour. Chinese culture shows strong collectivism, high‐power distance and long‐term concept tendency. The integration concept of mean thinking is not conducive to the prohibitive voice. Collectivism focuses on the characteristics of organizational harmony and inhibits employees from expressing conflicting voice. In addition, power distance is one of the important cultural roots of the lack of voice in Chinese organizations. To promote voice in the context of Chinese culture, the unique influence of Chinese culture on voice behaviour should be more fully considered. The organization needs to verify the ways of voice, protect the privacy of voice behaviour, continually provide feedback on voice behaviour and set up special encouragement for prohibitive voice. In the work situation, the supervisor should encourage informal communication among supervisors, subordinates and coworkers to enhance personal relationships. In view of the strong concept of face maintenance and high‐power distance of employees in Chinese culture, the implementation of informal voice behaviour mechanism may be conducive to promote voice behaviour.

Individuals spend most of their time in the organization, and it is their lifelong pursuit to become an insider of the team. Especially influenced by traditional culture and collectivism, being a member of the "big family" as an organization member is an important symbol of workplace success. Under the cultural origin of “Death for a confidant," employees with insider identity perception will be loyal to the organization, carry forward the spirit of ownership and make more contributions to the organization. Therefore, hospitals should take humanized management measures such as respecting nurses and treating nurses fairly, so that nurses can truly become "insiders" of enterprises.

In essence, becoming embedded in one's workplace is a concrete reflection of the quality of the relationship between employees and the organization. High‐work embedding means that employees have a close relationship with the work organization and employees will carry out behaviours that are more positive. Embedded human resource strategy is an important measure for enterprises to improve the embedding level of employees. Therefore, hospitals should formulate a series of resource management policies from a strategic perspective. For example, long‐term employment security, enterprise pension plan and work–family balance plan can enhance their loyalty and attachment to the organization and reduce their turnover intention, thus increasing the work embedding level of employees.

4.3. Limitations and future research

This study only focused on the individual voice behaviour itself, but the voice process can be divided into two stages: information processing stage and idea implementation stage. This hypothesis model is not supported by empirical evidence. Future studies can test these two stages in a unified model. For example, existing research seldom considered voice behaviour quality in the stage of information processing. A large number of scholars have focused on voice behaviour itself but considered the quantity and quality of voice behaviour less. Therefore, future studies can expand the construction of voice from perspective of voice behaviour quality. In the stage of idea implementation, different characteristics of managers, such as executive power, adjust focus, control point and power motive, may also affect the effect of idea implementation.

Measurement of employee's voice was taken by the self‐assessment approach. The homologous variance may influence on the results of the study. In addition to the supervisor, the staff can speak up to co‐workers. Therefore, only the supervisor evaluation method to measure employee voice behaviour limits the objectivity of the results of the study. Given this, future research should adopt the method of multiple evaluations to collect data about voice behaviour to different people, to draw more accurate research conclusions.

One strength of this study is it is a cross‐cultural study of voice behaviour. At present, foreign scholars' research on voice behaviour was mainly based on data from Western culture, with more a more individualistic cultural orientation. While under the Eastern cultural background, scholars may have different interpretations of voice behaviour. Voice behaviour is closely related to individual demographic characteristics, organizational environment and social environment, which is deeply influenced by social culture. East and West have different cultural traditions and institutional arrangements, so the influencing factors, generating mechanisms and results of voice behaviour in the context of Eastern and Western cultures should be different. For example, in the context of Eastern culture, people's strong sense of face and large power distance within the organization was not conducive to the implementation of voice behaviour. Therefore, it is necessary for future scholars to conduct cross‐cultural research on employee voice behaviour to improve the universality of research conclusions.

5. CONCLUSION

This study offers new perspective of voice by analysing voice value from the perspective of the speaker. This change of perspective highlights how voice is a potential way for the group insiders to improve self‐leadership. Based on our findings, when nurses dare to voice, nurses’ self‐leadership can be enhanced through perceived insider status improving, especially for nurses who dare to prohibitive voice.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ZG, LVS, FL, FG: Conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. ZG, LVS: Drafting of the manuscript or manuscript revision for important intellectual content. ZG, FL, FG: Final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. ZG, LVS: Accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the ethics committee of Liaocheng University with written informed consent from all participants. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Liaocheng University (2017_7_14). All participants have given written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors gratefully acknowledge all the participants.

Gong Z, Van Swol LM, Li F, Gilal FG. Relationship between nurse’s voice and self‐leadership: A time‐lagged study. Nurs Open. 2021;8:1038–1047. 10.1002/nop2.711

Funding information

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71801120), the Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science Research Youth Fund Project of China (18YJC630038), Shandong Social Science Planning Fund (19CQXJ05) and the China Scholarship Council (201908370108).

Contributor Information

Zhenxing Gong, Email: faheemgulgilal@yahoo.com.

Faheem Gul Gilal, Email: faheemgulgilal@yahoo.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- Avery, D. R. , & Quiñones, M. A. (2002). Disentangling the effects of voice: The incremental roles of opportunity, behavior and instrumentality in predicting procedural fairness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 81–86. 10.1037//0021-9010.87.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris, E. R. (2012). The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 851–875. 10.5465/amj.2010.0562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin, M. , Newton, D. W. , & Lepine, J. A. (2017). A meta‐analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: Identification of key associations, distinctions and future research directions. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 11–71. 10.1111/peps.12185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cody, J. L. , & Mcgarry, L. S. (2012). Small voices, big impact: Preparing students for learning and citizenship. Management in Education., 26(3), 150–152. 10.1177/0892020612445693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, G. , & Finch, S. (2005). Inference by eye: Confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. American Psychologist, 60(2), 170–180. 10.1037/0003-066X.60.2.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detert, J. R. , & Edmondson, A. C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: Taken‐for‐granted rules of self‐censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 461–488. 10.5465/amj.2011.61967925 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyne, L. V. , Ang, S. , & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392. 10.1111/1467-6486.00384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilal, F. G. , Channa, N. A. , Gilal, N. G. , Gilal, R. G. , Gong, Z. , & Zhang, N. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and brand passion among consumers: Theory and evidence. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management., 27, 2275–2285. 10.1002/csr.1963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z. , & Li, T. (2019). Relationship between feedback environment established by mentor and nurses' career adaptability: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(7), 1568–1575. 10.1111/jonm.12847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis. Journal of Educational Measurement, 51(3), 335–337. 10.1111/jedm.12050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. , & Bond, M. H. (1988). The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 5–21. 10.1016/0090-2616(88)90009-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, J. D. , & Neck, C. P. (2002). The revised self‐leadership questionnaire. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(8), 672–691. 10.1108/02683940210450484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, T. M. , Harrison, D. A. , Burris, E. R. , & Detert, J. R. (2015). Who gets credit for input? Demographic and structural status cues in voice recognition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1765. 10.1037/apl0000025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J. A. , Anderson, C. , & Moore, D. A. (2013). When overconfidence is revealed to others: Testing the status‐enhancement theory of overconfidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 122(2), 266–279. 10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J. A. , & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with Big Five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336. 10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Wu, L. , Liu, D. , Kwan, H. K. , & Liu, J. (2014). Insiders maintain voice: A psychological safety model of organizational politics. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(3), 853–874. 10.1007/s10490-013-9371-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J. , Farh, C. I. , & Farh, J. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two‐wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92. 10.5465/amj.2010.0176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manz, C. C. (2011). The leadership wisdom of Jesus: Practical lessons for today. Berrett‐Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- McClean, E. J. , Martin, S. R. , Emich, K. J. , & Woodruff, C. T. (2018). The social consequences of voice: An examination of voice type and gender on status and subsequent leader emergence. Academy of Management Journal, 61(5), 1869–1891. 10.5465/amj.2016.0148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. 10.1080/19416520.2011.574506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T. W. H. , & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Employee voice behavior: A meta‐analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 216–234. 10.1002/job.754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X. , Direnzo, M. S. , Xu, M. , & Duan, Y. (2014). When do emotionally exhausted employees speak up? Exploring the potential curvilinear relationship between emotional exhaustion and voice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 1018–1041. 10.1002/job.1948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamper, C. L. , & Masterson, S. S. (2002). Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(8), 875–894. 10.1002/job.175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Swol, L. M. , Paik, J. E. , & Prahl, A. (2018). Advice recipients: The psychology of advice utilization. In MacGeorge E. L., & Van Swol L. M. (Eds.), Oxford handbook of advice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.