Abstract

Aims The aim of this official guideline published and coordinated by the German Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) in cooperation with the Austrian Society for Gynaecology and Obstetrics (OEGGG) and the Swiss Society for Gynaecology and Obstetrics (SGGG) was to provide consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis based on an evaluation of the relevant literature.

Methods This S2k guideline represents the structured consensus of a representative panel of experts with different professional backgrounds commissioned by the Guideline Committee of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG.

Recommendations Recommendations on the epidemiology, aetiology, classification, symptomatology, diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis are given and special situations are discussed.

Key words: endometriosis, diagnosis, treatment, pelvic pain, guideline

I Guideline Information

Guideline programme of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG

For information about the guideline programme, please refer to the end of the guideline.

Citation format

Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis. Guideline of the DGGG, SGGG and OEGGG (S2k Level, AWMF Registry Number 015/045, August 2020). Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2021; 81: 422 – 446

Guideline documents

The complete long version together with a slide version of these guidelines and a list of the conflicts of interest of all authors involved are available on the homepage of the AWMF: http://www.awmf.org/guidelinen/detail/ll/015-045.html

Guideline group

Tab. 1 Lead author and/or coordinating lead author of the guideline.

| Author | AWMF professional society |

|---|---|

| PD Dr. Stefanie Burghaus | German Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e. V.] (DGGG) |

| Dr. Sebastian D. Schäfer | German Society of Gynaecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin e. V.] (DGGEF) |

| Prof. Dr. Uwe Andreas Ulrich | Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy [Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Gynäkologische Endoskopie] (AGE) |

Tab. 2 Contributing guideline authors.

| DGGG working group (AG)/AWMF/non-AWMF professional society/organisation/association | Mandate holder/author | Deputy/author |

|---|---|---|

| Professional Association of Gynaecologists | PD Dr. med. Stefanie Burghaus | Prof. Dr. med. Dr. phil. Dr. h. c. mult. Andreas D. Ebert |

| German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV) | Dr. med. Sebastian D. Schäfer | |

| German Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) | Prof. Dr. med. Uwe Andreas Ulrich | |

| German Society of Gynaecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine (DGGEF) | Dr. med. Volker Heinecke | |

| Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (AGE) | Prof. Dr. med. Jan Langrehr | |

| Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology | Prof. Dr. med. Matthias W. Beckmann | Dr. med. Christine Fahlbusch |

| Society of Gynaecological Oncology (AGO) | Prof. Dr. med. Tanja Fehm | PD Dr. med. Thomas Papathemelis |

| IMed Committee | Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Müller | PD Dr. med. Carolin C. Hack |

| German Society of Psychosomatic Gynaecology and Obstetrics (DGPFG e. V.) | PD Dr. med. Friederike Siedentopf | |

| Society of University Reproductive Medicine Centres (URZ) | PD Dr. med. Andreas Schüring | Prof. Dr. med. Katharina Hancke |

| Medical Society for Health Promotion (ÄGGF) | Dr. med. Christine Klapp | Dr. med. Heike Kramer |

| German Pathology Society | Prof. Dr. med. Dietmar Schmidt | Prof. Dr. med. Lars-Christian Horn |

| German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Medical Psychotherapy (DGPM) | Prof. Dr. med. Kerstin Weidner | PD Dr. med. Christian Brünahl |

| German Society for Rehabilitation Sciences | Dr. Iris Brandes, MPH | |

| German Reproductive Medicine Society (DGRM) | Prof. Dr. med. Katharina Hancke | |

| German College of Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM) | PD Dr. med. Christian Brünahl | Prof. Dr. med. Kerstin Weidner |

| German Radiology Society | Dr. med. Christian Houbois | |

| German Pain Society | Prof. Dr. med. Winfried Häuser | |

| German Society of Thoracic Surgery (DGT) | Dr. med. Wojciech Dudek | Prof. Dr. med. Dr. h. c. Horia Sirbu |

| German Society of Urology | Dr. med. Isabella Zraik | |

| Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (OEGGG) | Assoc. Prof. Priv.-Doz. Dr. Beata Seeber | Prof. Dr. med. Peter Oppelt |

| Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (SGGG) | Prof. Dr. med. Michael Müller | Dr. med. Peter Martin Fehr |

| Czech Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics | Prim. Dr. med. Radek Chvatal | Dr. med. Jan Drahoňovský |

| Endometriosis research foundation (SEF) | Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Karl-Werner Schweppe | Prof. Dr. med. Sylvia Mechsner |

| European endometriosis league (EEL) | Prof. Dr. med. Stefan. P. Renner | Dr. med. Harald Krentel |

| Endometriosis association Germany | Daniela Soeffge | Dr. Heike Matuschewski |

| Endometriosis association Austria | Ines Mayer | Armelle Müller |

Dr. Monika Nothacker, MPH (AWMF Institute for Medical Knowledge Management), who took over moderation of the guideline, is gratefully acknowledged.

Gender note

For better readability, simultaneous use of all language forms is omitted throughout. All female or male references to persons apply to each sex.

Abbreviations employed

- ASRM

American Society for Reproductive Medicine

- COC

combined oral contraceptive

- DIE

deep infiltrating endometriosis

- DRG

diagnosis related groups

- EAOC

endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer

- GnRH

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- HIFU

high frequency ultrasound

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PMWA

percutaneous microwave ablation

- UAE

uterine artery embolisation

II Guideline Application

Purpose and objectives

The purpose of this guideline is to provide information and advice about the diagnosis, treatment and further care of endometriosis as well as specific situations for women with already confirmed or suspected endometriosis and for physicians who treat women with endometriosis.

In addition, the information is intended to form the basis for joint decision-making in certified endometriosis clinics, units or centres. The defined statements and recommendations will also be used to develop quality indicators.

Area of patient care

Inpatient, outpatient and day-care sector.

Target user group/target audience

This guideline is aimed at the following groups: office-based gynaecologists, gynaecologists in hospitals, reproductive medicine physicians, pathologists, urologists, visceral surgeons, radiologists, psychosomatic specialists and psychologists, pain therapists, patients with or suspected to have endometriosis, specialists in rehabilitation medicine, general physicians, paediatricians and womenʼs interest groups that represent womenʼs interests (patient and self-help organisations).

Additional targeted groups (for information purposes): nursing staff, members of occupational groups involved in the care of patients with confirmed or suspected endometriosis (e.g., stoma therapists), funding bodies and German national and regional health policy institutions and decision-makers.

Adoption and period of validity

The validity of this guideline was confirmed by the executive boards/heads of the participating professional societies/working groups/organisations/associations, as well as by the boards of the DGGG and the DGGG Guidelines Commission and of the SGGG and OEGGG in July 2020 and was thus approved in its entirety. This guideline is valid from 01.08.2020 to 31.07.2023. Because of the contents of this guideline, this period of validity is only an estimate.

III Methodology

Basic principles

The method used to prepare this guideline was determined by the class to which this guideline was assigned. The AWMF Guidance Manual (version 1.0) has set out the respective rules and requirements for different classes of guidelines. Guidelines are differentiated into the lowest (S1), intermediate (S2) and highest (S3) class. The lowest class is defined as a set of recommendations for action compiled by a non-representative group of experts. In 2004, the S2 class was divided into two subclasses: a systematic evidence-based subclass (S2e) and a structural consensus-based subclass (S2k). The highest S3 class combines both approaches.

This guideline was classified as: S2k .

Grading of recommendations

Grading of evidence based on the systematic search, selection, evaluation and synthesis of the evidence base followed by a grading of the evidence is not envisaged for S2k-level guidelines. The individual statements and recommendations are only differentiated by syntax, not by symbols ( Table 3 ):

Tab. 3 Grading of recommendations (based on Lomotan et al. Qual Saf Health Care 2010).

| Description of binding character | Expression |

|---|---|

| Strong recommendation, highly binding | must/must not |

| Recommendation, moderately binding | should/should not |

| Open recommendation, not binding | may/may not |

Statements

Expositions of explanations of specific facts, circumstances or problems without any direct recommendations for action included in this guideline are referred to as “Statements”. It is not possible to provide any information about the grading of evidence for these statements.

Achieving consensus and strength of consensus

At structured NIH-type consensus-based conferences (S2k/S3 level), authorised participants attending the session vote on draft statements and recommendations. The process is as follows. A recommendation is presented, its contents are discussed, proposed changes are put forward, and finally, all proposed changes are voted on. If a consensus has not been achieved (≤ 75% of votes), there is another round of discussions, followed by a repeat vote. Finally, the extent of consensus is determined based on the number of participants ( Table 4 ).

Tab. 4 Classification showing the extent of agreement for consensus-based decisions.

| Symbol | Strength of agreement | Extent of agreement in percent |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | Strong consensus | > 95% of participants agree |

| ++ | Consensus | > 75 – 95% of participants agree |

| + | Majority agreement | > 50 – 75% of participants agree |

| – | No consensus | < 51% of participants agree |

Expert consensus

As the name already implies, this refers to consensus decisions taken with regard to Recommendations/Statements without a prior systematic search of the literature (S2k) or for which evidence is lacking (S2e/S3). The term “expert consensus” (EC) used here is synonymous with terms used in other guidelines such as “good clinical practice” (GCP) or “clinical consensus point” (CCP). The strength of the recommendation is graded as previously described in the section “Grading of recommendations”, i.e., purely semantically (“must”/“must not” or “should”/“should not” or “may”/“may not”) and without the use of symbols.

IV Guideline

1 Epidemiology, aetiology, morbidity and manifestation of endometriosis

Figures on the prevalence and incidence vary according to the clinical situation and are also influenced by selective consideration.

Different concepts were developed to describe the possible causes for the development and persistence of the disease (e.g., implantation theory 1 , coelom metaplasia theory 2 , archimetra or “tissue injury and repair concept” 3 , 4 , but without finding a satisfactory final explanation. Rather, from combining the various concepts, it is assumed that genetic defects and epigenetic phenomena as well as other influences provide the conditions for specific changes to take place during implantation and metaplasia that will allow foci of endometriosis to develop in a milieu that is foreign for these cells. Important factors influencing this process include hyperperistalsis, arising from adaptations due to evolutional biology 4 , hyperoestrogenisation, hyperperistalsis, inflammatory and immune processes, prostaglandin metabolism, angiogenesis, oxidative stress and various others 5 , 6 , 7 .

The following are affected in decreasing frequency: pelvic peritoneum, ovaries, sacrouterine ligaments, rectovaginal septum/vaginal fornix, extragenital manifestations (e.g., rectosigmoid and bladder).

2 Basic principles of endometriosis classification (clinical/intraoperative, histological, DRG system)

2.1 Clinical/intraoperative classification of endometriosis

A clinical/intraoperative distinction depending on the location and extent is made between the following endometriosis entities: peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) and uterine adenomyosis.

2.2 Histological classification of endometriosis

2.3 DRG system of endometriosis (ICD-10-GM-2019, OPS-2019)

Endometriosis is classified in the DRG system according to ICD-10-GM-2019 and this forms the basis of the consideration of endometriosis sites in section 6 ff below.

3 Symptoms and basic principles of diagnosis of endometriosis (investigation algorithm)

4 Basic principles of treatment of endometriosis

4.1 Hormonal treatment of endometriosis

The principle of effective hormonal treatment consists of induction of therapeutic amenorrhoea. In German-speaking countries, only the progestin dienogest and the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue leuprorelin acetate have been approved to date for the hormonal treatment of endometriosis.

Primary hormonal therapy

There have been increasing attempts to use progestins and oral contraceptives as first-line treatment prior to surgical diagnosis or treatment. There was no significant difference between primary pharmacological and operative therapy in pain relief 17 . However, valid data are lacking that would allow assessment in the long term of symptom relief, the probability of recurrence and the influence on fertility with primary hormonal therapy.

Postoperative hormonal therapy

The rate of endometrioma recurrence and the rate of symptoms such as dysmenorrhoea and chronic pain can be reduced by postoperative therapy with combined oral contraceptives in a long-term cycle 18 . This was also shown for dienogest 19 . Use of GnRH analogues for 6 instead of 3 months significantly reduced the risk of recurrence 20 .

4.2 Pharmacological, non-hormonal therapy of endometriosis

Analgesics

Analgesics are used for the symptomatic treatment of patients with pain. In a Cochrane review from 2017 the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients with endometriosis was analysed. Only two randomised controlled studies were identified, so that a conclusion regarding the effectiveness of NSAIDs and also subgroup analyses are not possible. The data regarding NSAIDs for (primary) dysmenorrhoea are much better and NSAIDs appear to be effective for the relief of menstrual pain 21 .

4.3 Surgical treatment of endometriosis

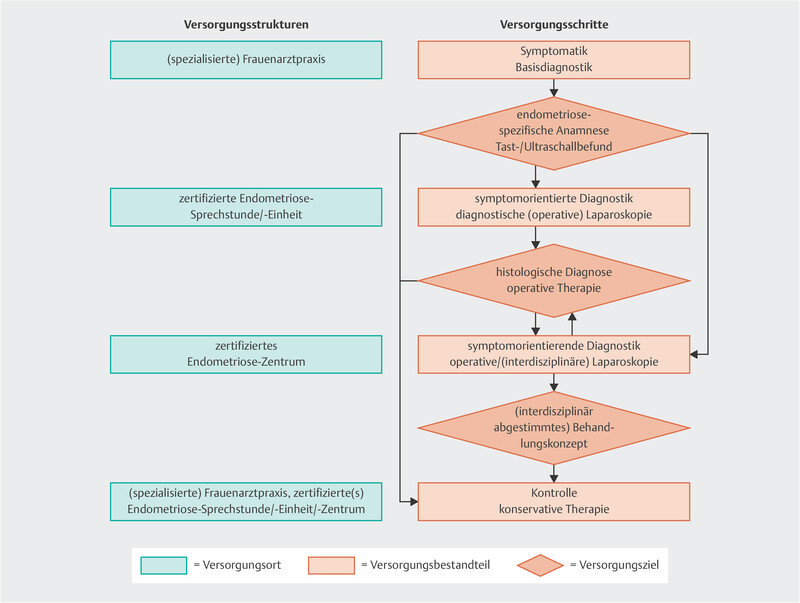

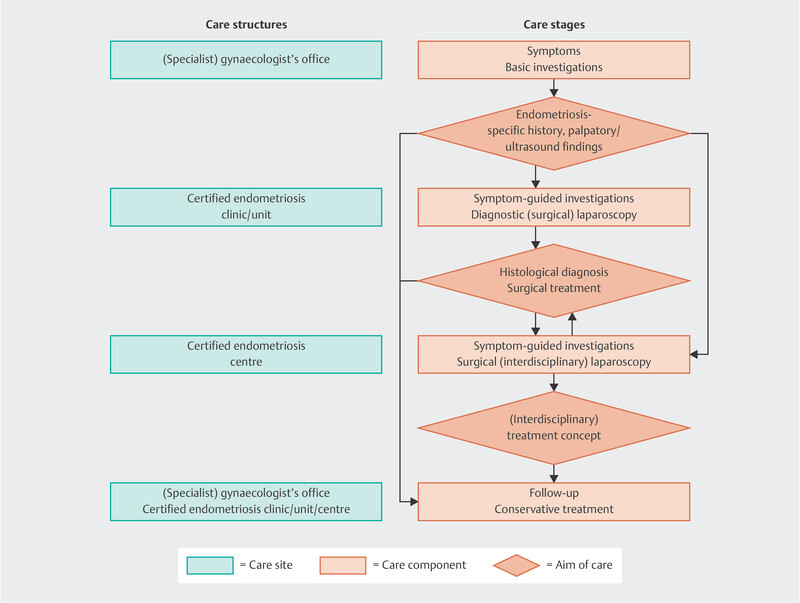

5 Care structures for patients with suspected or confirmed endometriosis

Abb. 1.

Agreed care algorithm of the guideline group (based on expert consensus, strength of consensus ++).

6 Diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis according to site

6.1 Endometriosis of the uterus (N80.0)

6.2 Endometriosis of the ovary and tube (N80.1 and N80.2)

The potential negative influence of the endometrioma on ovarian reserve and function is probably caused by stretching of the ovarian cortex, local inflammatory processes, oxidative stress and fibrosis of the ovary 22 .

If assisted reproduction is planned, the prospect of success is probably not increased by prior endometrioma removal 22 , 23 .

6.3 Endometriosis of the pelvic peritoneum/peritoneal endometriosis (N80.3)

6.4 Endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum and vagina (N80.4)

6.5 Endometriosis of the bowel (N80.5)

6.6 Endometriosis in a skin scar (N80.6)

6.7 Endometriosis in the bladder and of the ureter (N80.8)

Even though isolated cases of endometriosis of the bladder treated pharmacologically are described in the literature 25 , the treatment of endometriosis of the bladder in most cases consists of partial cystectomy 26 , 27 . If the endometriosis nodule is located in proximity to the ureter ostia, a double J catheter is inserted immediately before the intervention.

In the case of endometriosis of the ureter, the first step is to attempt ureter decompression without segment resection or ureter implantation; ureteroneocystostomy should be performed only if this fails and the ureter and renal pelvis do not recover.

6.8 Rare extragenital endometriosis locations, extra-abdominal endometriosis (N80.8)

7 Special endometriosis situations

7.1 Endometriosis in adolescents

7.2 Endometriosis and desire for children

7.3 Endometriosis: pregnancy and delivery

With regard to pregnancy , there is now a fairly large number of studies that present the increased risks as follows:

7.4 Endometriosis and pain

7.5 Endometriosis and cancer

A patient with endometriosis has a very low risk overall of developing ovarian cancer because of the only slightly increased ovarian cancer risk as the lifetime risk of this is low anyway at 1.3%. In most of the published studies on endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC), the risk of the disease in endometriosis patients is classified as moderate (RR, SIR or OR: 1.3 – 1.9) 37 , 38 , 39 . Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy can be discussed, however, e.g., in perimenopausal women with endometriomas > 6 – 9 cm, since the risk of ovarian cancer in these patients is increased up to 13.2 times. Removal of the endometrioma alone does not reduce the risk in this group of patients 40 .

7.6 Endometriosis and psychosomatic aspects

7.7 Endometriosis and association with other diseases

8 Rehabilitation, follow-up care and self-help

9 Integrative therapy in patients with endometriosis

There are a few small prospective randomised studies that investigated the different integrative therapy methods with regard to the effectiveness of pain reduction in primary dysmenorrhoea, though evidence of existing endometriosis very rarely had to be provided in these studies. The pain reduction was mainly in the placebo, comparator or control group and the active treatment group was rarely superior. The number of included patients/participants was usually rather low. The maximum study period or follow-up period was 6 to 12 months. The data are insufficient with regard to fertility.

Various Chinese herbal medicines, calcium, phototherapy, acupuncture, electroacupuncture, moxibustion, injection of local anaesthetics into pain trigger points, manual therapy and physical exercise can be used for the primary treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The conflicts of interests of the authors are listed in the long version of the guideline./Die Interessenkonflikte der Autoren sind in der Langfassung der Leitlinie aufgelistet.

Consensus-based statement 1.S1.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Reliable data on the prevalence and incidence of endometriosis are not available.

Consensus-based statement 1.S2.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Because of the unclear aetiology of endometriosis, causal therapy is not possible.

Reference: 8

Consensus-based recommendation 2.E1.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

If an intraoperative diagnosis of endometriosis is suspected, the diagnosis must be confirmed histologically.

Consensus-based recommendation 2.E2.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

The rASRM score (version 1996) must be documented at all operations on patients with a suspected diagnosis of endometriosis.

Consensus-based recommendation 2.E3.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

The Enzian classification (version 2011) must be used in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis including uterine adenomyosis.

Consensus-based statement 2.S3.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

The symptoms pain and infertility are not recorded with the rASRM score and the Enzian classification. The classifications also do not predict the course of the disease.

Consensus-based statement 2.S4.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Endometriosis is the occurrence of endometrium-like groups of cells consisting of groups of endometrioid glandular cells and/or stromal cells outside the uterine cavity.

Consensus-based recommendation 2.E4.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

The primary histological diagnosis of endometriosis is made by haematoxylin-eosin staining. If histological diagnosis of macroscopically suspected endometriosis is negative, additional tests (e.g., additional sections, CD10 or haemosiderin staining) should be performed.

Consensus-based statement 2.S5.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Endometriosis of the body of the uterus (clinically: adenomyosis or uterine adenomyosis or internal genital endometriosis) is defined histopathologically as the finding of a focus of endometriosis in the myometrium at a distance from the endo-myometrial boundary at medium magnification (100 ×) equivalent metrically to 2.5 mm.

Consensus-based recommendation 2.E5.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

In bowel specimens resected because of deep infiltrating endometriosis involving bowel, a statement about the resection margin status must be made in the histopathological report.

Consensus-based recommendation 3.E6.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Endometriosis-specific symptoms (dysmenorrhoea, dysuria, dyschezia, dyspareunia and infertility) and nonspecific symptoms such as pelvic pain must be recorded when taking a gynaecological history. This can be done with a specific endometriosis questionnaire.

Reference: 12

Consensus-based recommendation 3.E7.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

If deep infiltrating endometriosis or ovarian endometriosis is suspected, bilateral renal ultrasound must be performed.

Reference: 13

Consensus-based statement 3.S6.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Laparoscopy with intraoperative biopsy for histological examination is the gold standard to confirm a suspected diagnosis of endometriosis.

Consensus-based statement 3.S7.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Biomarkers are not suitable for the diagnosis of endometriosis.

Reference: 8

Consensus-based recommendation 4.E8.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

A suitable progestin (e.g., dienogest) should be used as first-line drug in the symptomatic pharmacological treatment of endometriosis.

Consensus-based recommendation 4.E9.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++ to +++

Combined oral contraceptives (strength of consensus ++)

Other progestins including topical use (strength of consensus +++) or

GnRH analogues (strength of consensus ++)

can be used as second-line treatment.

Consensus-based recommendation 4.E10.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Before starting second-line treatment, re-evaluation in a facility specialising in the care of patients with endometriosis should be considered.

Consensus-based recommendation 4.E11.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Treatment with GnRH analogues should be supplemented by add-back treatment with a suitable oestrogen-progestin combination. The consequences of oestrogen deficiency can thereby be minimised without influencing the therapeutic efficacy of the GnRH analogue.

Consensus-based statement 4.S8.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Long-term hormonal therapy used continuously is effective both in the treatment of endometriosis-associated symptoms and for prolonging the recurrence-free interval.

Reference: 8

Consensus-based recommendation 4.E12.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

In the symptomatic patient with deep infiltrating endometriosis, complete resection should be attempted if the expected benefits of pain reduction outweigh the disadvantages of possible operation-related organ impairment (e.g., sexuality and disorders of bladder, bowel, sensory and motor function).

Reference: 17

Consensus-based recommendation 4.E13.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

For recurrent symptoms, pharmacological treatment should be given before further surgical treatment unless there are compelling reasons for surgery (e.g., organ destruction).

Reference: 17

Consensus-based recommendation 5.E14.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Patients with endometriosis should be treated by an interdisciplinary team. This team should include all necessary specialties in a cross-sector network. This can be achieved in a certified structure (clinic, centre) ( Fig. 1 ).

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E15.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

The suspected diagnosis adenomyosis of the uterus can be made by transvaginal sonography and/or MRI. Transvaginal sonography must be used as first-line diagnostic investigation, and MRI as second-line investigation. Both methods are equivalent as regards their reliability.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E16.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Because of the limited sensitivity and specificity of biopsy-based confirmation of adenomyosis of the uterus, a biopsy should not be done.

Consensus-based statement 6.S9.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

All established forms of hormone therapy (combined oral contraceptives, progestins, suitable progestin IUD, GnRH analogues) are effective in the treatment of adenomyosis-associated symptoms. There is no evidence that one substance class is superior.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E17.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Interventional treatment with high-frequency ultrasound (HIFU), uterine artery embolisation (UAE), transcervical electroablation, percutaneous microwave ablation (PMWA) to treat adenomyosis of the uterus must be used only in studies.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E18.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Cystic or focal adenomyosis of the uterus can be resected for control of pain and bleeding.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E19.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Hysterectomy can be recommended for symptoms of adenomyosis of the uterus when family planning is complete.

Reference: based on the S3 guideline “Indication and method of hysterectomy for benign disease” in version 1.0 April 2015, AWMF no. 015/070 with weakening of the level of recommendation.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E20.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Before determining the treatment strategy for ovarian endometriosis, anti-Müllerian hormone can be measured as a marker of ovarian reserve.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E21.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Ovarian function must be considered when deciding on the treatment of endometriomas.

Consensus-based statement 6.S10.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

When endometriomas are removed in cases of recurrence, there is an increased risk for premature loss of ovarian function.

Consensus-based statement 6.S11.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

All known operative procedures for endometriomas reduce ovarian reserve.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E22.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

When an endometrioma is diagnosed, the simultaneous presence of deep infiltrating endometriosis should be excluded.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E23.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Transvaginal sonography must be used to assess the ovaries when endometriosis is confirmed or suspected.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E24.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

If the result of sonography of the ovary is suspicious, the surgical histological diagnosis must be confirmed observing oncological safety.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E25.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

To prevent endometrioma recurrence, systemic hormone therapy (preferably with COC) can be used long-term.

Consensus-based statement 6.S12.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

With primary surgical treatment of an endometrioma, complete removal compared with fenestration of the ovary increases the spontaneous pregnancy rate and is superior to pharmacological treatment with regard to pain reduction and avoidance of recurrence.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E26.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

If symptomatic peritoneal endometriosis is diagnosed intraoperatively, primary complete removal should be attempted. Planned second-look laparoscopy with or without pretreatment must not be performed.

Consensus-based statement 6.S13.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Ablation and excision of peritoneal endometriosis are equivalent with regard to pain reduction.

Reference: 24

Consensus-based statement 6.S14.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Surgical removal of peritoneal endometriosis leads to a significant reduction in the severity of dysmenorrhoea on the visual analogue scale (VAS). This effect was not shown for chronic pelvic pain, dyschezia and dyspareunia when peritoneal endometriosis was removed surgically.

Reference: 24

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E27.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

For symptomatic endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum and vagina, function-adapted complete resection should be performed.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E28.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Asymptomatic endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum and vagina without currently foreseeable, clinically significant secondary consequences (e.g., obstructive uropathy) does not have to be treated.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E29.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

A patient with haematochezia must have differential diagnostic investigations.

Consensus-based statement 6.S15.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

An asymptomatic patient with bowel endometriosis does not require any surgical intervention.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E30.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

A patient with bowel endometriosis must be treated in interdisciplinary consensus, in certified facilities as far as possible.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E31.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

In patients with endometriosis of the bowel renal sonography must be performed in the case of conservative treatment or pre- and postoperatively so as not to overlook clinically silent hydronephrosis.

Consensus-based statement 6.S16.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Surgical removal of an endometriosis lesion in a skin scar leads to symptom control and is the treatment of choice.

Consensus-based statement 6.S17.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Endometriosis of the bladder and/or ureter can have serious consequences, such as obstructive uropathy with potential consequent loss of renal function.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E32.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Symptomatic abdominal wall or umbilical endometriosis should be removed surgically.

Consensus-based recommendation 6.E33.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

For thoracic endometriosis and/or endometriosis-associated pneumothorax (including catamenial pneumothorax), conservative pharmacological measures should be used initially. If medical treatment fails or is contraindicated, thoracic surgery must be performed.

Consensus-based statement 7.S18.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

All forms of persistent pelvic pain (dysmenorrhoea, cyclical and non-cyclical pelvic pain) in adolescence can be symptoms of endometriosis.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E34.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

The primary treatment of suspected endometriosis in adolescence should be conservative pharmacological treatment.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E35.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

For refractory pain, laparoscopy should be performed to investigate the symptoms and, if applicable, remove any endometriosis, if possible in the same procedure.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E36.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Women with histologically confirmed endometriosis should be informed about the possibly impaired chances of pregnancy.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E37.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

For patients with infertility and endometriomas, treatment should be determined in an interdisciplinary setting in collaboration with a reproductive medicine centre.

Consensus-based statement 7.S19.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Treated or existing deep infiltrating endometriosis is not a contraindication to spontaneous delivery.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E38.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

In the case of existing or resected rectal endometriosis, no recommendation for a certain mode of delivery (i.e., spontaneous delivery versus section) can be expressed.

Consensus-based statement 7.S20.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Surgical treatment of deep infiltrating endometriosis in the region of the sigmoid, appendix/caecum, ileum or colon is not an indication for primary section.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E39.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

In patients with endometriosis and refractory chronic pelvic pain, a structured pain history must be taken.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E40.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

In patients with chronic pelvic pain, symptom-guided pain therapy can be considered in the following situations:

Insufficient pain reduction and/or

Intolerance and/or

Contraindications to surgical or hormonal therapy.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E41.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

The terminology and morphological diagnosis of endometriosis-associated cancer must be based on the current version of the WHO classification.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E42.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

The surgical treatment concept for patients with endometriosis in the premenopause should not be influenced by the slightly increased ovarian cancer risk.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E43.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Primary psychological assessment for anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis should take place in the context of basic psychosomatic care.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E44.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Patients with endometriosis and high stress due to mental symptoms must be offered psychotherapy, if possible within a multimodal treatment concept.

Consensus-based statement 7.S21.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Endometriosis can be associated with mental disorders such as increased anxiety and/or depression.

Consensus-based statement 7.S22.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Endometriosis can be associated with other chronic pain syndromes (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, fibromyalgia syndrome).

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E45.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Patients with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain must be investigated for the presence of other chronic pain syndromes.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E46.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

In the gynaecological examination, local (myofascial trigger points) and generalised hyperalgesia and increased pain sensitivity (allodynia) as evidence for central sensitisation must be noted.

Consensus-based recommendation 7.E47.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

In patients with endometriosis and associated pain syndromes, treatment options must be discussed with pain therapists and physicians specialising in psychosomatic medicine and psychotherapy or psychological psychotherapists.

Consensus-based recommendation 8.E48.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Rehabilitation/follow-up treatment for women with endometriosis should take place in a rehabilitation clinic certified for this disease.

Reference: 47

Consensus-based statement 8.S23.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Women with endometriosis must be informed of the services provided by the pension insurance organisations for rehabilitation and follow-up care.

Reference: 48

Consensus-based recommendation 8.E49.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

To deal with the physical and mental problems that can affect women with endometriosis, patients must be informed about self-help services.

Consensus-based recommendation 8.E50.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

The participation of women with endometriosis in structured educational or information events should be encouraged and supported.

Consensus-based recommendation 9.E51.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus ++

Endometriosis patients should be asked about the use of complementary medicine and alternative methods and advised if they wish.

Consensus-based recommendation 9.E52.

Expert consensus

Strength of consensus +++

Patients who use such methods must be informed of possible risks and, where applicable, interactions with standard treatments.

References/Literatur

- 1.Sampson J A. Metastatic or Embolic Endometriosis, due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue into the Venous Circulation. Am J Pathol. 1927;3:93–110.43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer R. Über den Stand der Frage der Adenomyositis, Adenomyome im allgemeinen und insbesondere über Adenomyositis seroepithelialis und Adenomyometritis sarcomatosa. Zentralbl Gynäkol. 1919;36:745–750. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leyendecker G, Kunz G, Noe M. Endometriosis: a dysfunction and disease of the archimetra. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:752–762. doi: 10.1093/humupd/4.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leyendecker G, Wildt L, Mall G. The pathophysiology of endometriosis and adenomyosis: tissue injury and repair. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:529–538. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1191-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordts S, Koninckx P, Brosens I. Pathogenesis of deep endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:872–8850. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koninckx P R, Ussia A, Adamyan L. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parazzini F, Esposito G, Tozzi L. Epidemiology of endometriosis and its comorbidities. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch M, Begum M R, Paniz E. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: a systematic review of international and national guidelines. BJOG. 2018;125:556–564. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clement P B, Young R H. Edinburgh, London, New York, Oxford, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Sydney: Elsevier; 2020. Atlas of Gynecologic Surgical Pathology. 4th ed; pp. 183–184. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockerham A Z. Adenomyosis: a challenge in clinical gynecology. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2012;57:212–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCluggage W G, Robboy S J. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2008. Mesenchymal uterine tumors, other than pure smooth muscle neoplasms, and adenomyosis; pp. 450–456. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burghaus S, Fehm T, Fasching P A. The International Endometriosis Evaluation Program (IEEP Study) – A Systematic Study for Physicians, Researchers and Patients. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:875–881. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-106895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palla V V, Karaolanis G, Katafigiotis I. Ureteral endometriosis: A systematic literature review. Indian J Urol. 2017;33:276–282. doi: 10.4103/iju.IJU_84_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schliep K C, Chen Z, Stanford J B. Endometriosis diagnosis and staging by operating surgeon and expert review using multiple diagnostic tools: an inter-rater agreement study. BJOG. 2017;124:220–229. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu D, Hu M, Hong L. Clinical efficacy of add-back therapy in treatment of endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:513–523. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai H W, Wang P H, Huang B S. Low-dose add-back therapy during postoperative GnRH agonist treatment. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaichian S, Kabir A, Mehdizadehkashi A. Comparing the Efficacy of Surgery and Medical Therapy for Pain Management in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2017;20:185–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zorbas K A, Economopoulos K P, Vlahos N F. Continuous versus cyclic oral contraceptives for the treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:37–43. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3641-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adachi K, Takahashi K, Nakamura K. Postoperative administration of dienogest for suppressing recurrence of disease and relieving pain in subjects with ovarian endometriomas. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:646–649. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2016.1147547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Q, Mao H, Xu Y. Can postoperative GnRH agonist treatment prevent endometriosis recurrence? A meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke R O, Farquhar C.Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea Cochrane Database Syst Rev 201507CD001751 10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keyhan S, Hughes C, Price T. An Update on Surgical versus Expectant Management of Ovarian Endometriomas in Infertile Women. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:204792. doi: 10.1155/2015/204792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tao X, Chen L, Ge S. Weigh the pros and cons to ovarian reserve before stripping ovarian endometriomas prior to IVF/ICSI: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley K A, Benton A S, Deimling T A. Surgical Excision Versus Ablation for Superficial Endometriosis-Associated Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angioni S, Nappi L, Pontis A. Dienogest. A possible conservative approach in bladder endometriosis. Results of a pilot study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31:406–408. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2015.1006617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Ceccarello M. Total laparoscopic bladder resection in the management of deep endometriosis: “take it or leave it.” Radicality versus persistence. Int Urogynecol J. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-04107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knabben L, Imboden S, Fellmann B. Urinary tract endometriosis in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis: prevalence, symptoms, management, and proposal for a new clinical classification. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hjordt Hansen M V, Dalsgaard T, Hartwell D. Reproductive prognosis in endometriosis. A national cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:483–489. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S G, Seo H G, Kim Y S. Primiparous singleton women with endometriosis have an increased risk of preterm birth: Meta-analyses. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60:283–288. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.3.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conti N, Cevenini G, Vannuccini S. Women with endometriosis at first pregnancy have an increased risk of adverse obstetric outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1795–1798. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.968843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berlac J F, Hartwell D, Skovlund C W. Endometriosis increases the risk of obstetrical and neonatal complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:751–760. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zullo F, Spagnolo E, Saccone G. Endometriosis and obstetrics complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:667–6.72E7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigano P, Corti L, Berlanda N. Beyond infertility: obstetrical and postpartum complications associated with endometriosis and adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalani S, Choudhry A J, Firth B. Endometriosis and adverse maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1854–1865. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weidner K, Neumann A, Siedentopf F. Chronischer Unterbauchschmerz: Die Bedeutung der Schmerzanamnese. Frauenarzt. 2015;56:982–987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauser W, Bock F, Engeser P. [Recommendations of the updated LONTS guidelines. Long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain] Schmerz. 2015;29:109–130. doi: 10.1007/s00482-014-1463-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somigliana E, Vigano P, Parazzini F. Association between endometriosis and cancer: a comprehensive review and a critical analysis of clinical and epidemiological evidence. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim H S, Kim T H, Chung H H. Risk and prognosis of ovarian cancer in women with endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1878–1890. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zafrakas M, Grimbizis G, Timologou A. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Front Surg. 2014;1:14. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomsen L H, Schnack T H, Buchardi K. Risk factors of epithelial ovarian carcinomas among women with endometriosis: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:761–778. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L C, Hsu J W, Huang K L. Risk of developing major depression and anxiety disorders among women with endometriosis: A longitudinal follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans S, Fernandez S, Olive L. Psychological and mind-body interventions for endometriosis: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2019;124:109756. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lagana A S, La Rosa V L, Rapisarda A MC. Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:323–330. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S119729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coloma J L, Martinez-Zamora M A, Collado A. Prevalence of fibromyalgia among women with deep infiltrating endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146:157–163. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alphen aan den Rijn: Wolters Kluwer; 2018. Veasley: Chronic overlapping Pain Conditions; pp. 87–111. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu C C, Chung S D, Lin H C. Endometriosis increased the risk of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis: a population-based study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37:1413–1418. doi: 10.1002/nau.23462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schweppe K W, Ebert A D, Kiesel L. Endometriosezentren und Qualitätsmanagement. doi:10.1007/s00129-009-2484-x Gynäkologe. 2010;43:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahmenkonzept zur Nachsorge für medizinische Rehabilitation nach § 15 SGB VI der Deutschen RentenversicherungStand: Juni 2015 (in der Fassung vom 1. Juli 2019). Accessed October 31, 2019 at:https://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Experten/infos_reha_einrichtungen/konzepte_systemfragen/konzepte/rahmenkonzept_reha_nachsorge.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

- 49.Kofahl C. [Collective patient centeredness and patient involvement through self-help groups] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019;62:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s00103-018-2856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hundertmark-Mayser J, Möller-Bock B.Selbsthilfe im Gesundheitsbereich. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes, Heft 23Herausgegeben vom Robert-Koch-Institut am 1. August 2004. Accessed October 31, 2019 at:http://www.gbe-bund.de/pdf/Heft23.pdf