Abstract

Schools are an attractive setting for implementation of mindfulness-based programs because mindfulness practices, by their very nature, align with a wide range of core educational goals. The present study investigated the effects of an 8-week (16 session) school-based mindfulness program for young children across 8 classrooms (K through 2) using a quasi-experimental delayed-intervention control group design. Results indicated that the mindfulness program was associated with significant improvements in teacher ratings of externalizing and prosocial behaviors. Program outcomes were not associated with child sex or race/ethnicity, but did vary by grade. Descriptive analyses suggest that outcomes tended to be more positive in classrooms with higher levels of teacher and student engagement. Results of the present study add to the growing knowledge base on the positive effects of school-based mindfulness programs and point to a need for more rigorous inquiry into the extent to which students and teachers are engaged with mindfulness programs both during the program itself and in their day to day functioning.

Keywords: Mindfulness, School-based mindfulness, Implementation fidelity, Prosocial behavior, Externalizing behavior, Education

Highlights

Teacher ratings of prosocial behavior and externalizing behavior improved after a 16-session mindfulness program.

Program outcomes differed by grade but not across child sex and race/ethnicity.

Teacher and student engagement in the mindfulness program was associated with more positive outcomes.

Social and emotional learning (SEL) programs in the schools focus on developing a wide range of students’ interpersonal, self-regulatory, and emotional competencies. Mindfulness-based SEL programs aim to develop these competencies through the cultivation of children’s ability to pay attention to the present moment with curiosity and nonjudgment (Bakosh et al., 2016; Kabat‐Zinn, 2003). Mindfulness-based SEL programs are increasingly being used with children and adolescents to support a range of health, academic, and social outcomes. A growing body of research has shown positive effects on executive functions (Black 2015; Dunning et al., 2019), mental health (Black, 2015; Kallapiran et al., 2015; Zoogman et al., 2015), academic performance (Bakosh et al., 2016), and socioemotional outcomes (e.g., self-regulation, stress reduction) (Black, 2015; Flook et al., 2015). Research has also suggested that mindfulness programs are feasible and acceptable for diverse groups of youth (Flook et al., 2015; Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016). Not surprisingly, schools have become a rapidly growing area for implementation of mindfulness programs (Felver & Jennings, 2016).

Schools are an attractive setting for implementation of these kinds of programs because mindfulness practices, by their very nature, align with core educational goals, including emotional self-regulation, stress-reduction, prosocial behavior, and attentional control (Meiklejohn et al., 2012; Zenner et al., 2014). The pattern of research on outcomes of school-based mindfulness programs parallels the broader findings for mindfulness programs, showing improvements in mental health outcomes (Carsley et al., 2018; Joyce et al., 2010), academic achievement (Bakosh et al., 2016; Beauchemin et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2016), prosocial behavior (Flook et al., 2015), emotional regulation (Arch & Craske, 2006; Coffey & Hartman, 2008), and attention (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016). The magnitude of the effect sizes in this research has generally been small to moderate, with considerable variability across populations, settings, and programs (Carsley et al., 2018; Zoogman et al., 2015). This variability may be due to a combination of methodological challenges and implementation factors that are inherent to the study of mindfulness programs in schools and other contexts.

Several comprehensive reviews of mindfulness research have documented important methodological considerations that limit conclusions about the efficacy of mindfulness programs (Davidson and Kaszniak, 2015; Van Dam et al., 2018). Among the most common methodological limitations in research on mindfulness programs is ambiguity in the conceptualization of mindfulness. Programs differ in the way that mindfulness is operationalized and which specific practices are emphasized, complicating the interpretation of program outcomes (Bishop et al., 2006; Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Van Dam et al., 2018). Other common methodological limitations include the lack of comparisons to “active” control groups (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Greenberg & Harris, 2012) and a heavy reliance on self-report measures (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Eklund et al., 2017; Van Dam et al., 2018). In addition to the inherent risks of social desirability and demand characteristics, the use of self-report or first-person measures may present unique challenges for measuring mindfulness processes and outcomes (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Van Dam et al., 2018). Changes that result from mindfulness practice may influence the reliability and construct validity of self-report measures, especially with younger children (M. S. Goodman et al., 2017). For these reasons, several researchers have recommended the use of “second-person” reports by outside observers as a strategy to assess outcomes in mindfulness programs (Dunning et al., 2019; Eklund et al., 2017; M. S. Goodman et al., 2017).

In addition to these methodological limitations, outcome research for school-based mindfulness programs is complicated by a range of factors related to implementation (Burke, 2010; Dariotis et al., 2017). Mindfulness programs in the schools differ in the extent to which they account for important contextual factors that could contribute to outcomes, such as developmental considerations, cultural context, and race or ethnicity (Burke, 2010; Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Fung et al., 2019; Goodman et al., 2017). There is also considerable variability in the extent to which mindfulness programs are integrated into the existing school context rather than delivered as a separate program. For instance, Dariotis and colleagues (2017) found that barriers to active engagement in the program included the adequacy of the physical environment, the timing of the program, and the extent to which students had to miss other activities in order to participate. Accordingly, lack of time and student disengagement with the program have been cited as barriers to implementation (Joyce et al., 2010).

Because of these factors, researchers have stressed the importance of documenting treatment or implementation fidelity for mindfulness programs in schools and other settings (Gould et al., 2016; Kechter et al., 2019). Treatment fidelity reflects a systematic assessment of the degree to which an intervention is implemented consistently and as intended (Gould et al., 2016; Kechter et al., 2019). Higher levels of fidelity are generally associated with better program outcomes and can enhance understanding of factors affecting response to the interventions (Greenberg and Harris, 2012). Gould and colleagues (2016) outline four common dimensions for assessing whether a program has been implemented with fidelity, including the extent to which: (a) a program’s core components were delivered as designed (adherence), (b) the magnitude of exposure is specified (dosage), (c) the content was implemented as intended (quality), and (d) participants were engaged in the program (responsiveness).

One aspect of implementation fidelity that is of particular relevance in school-based mindfulness research is the degree of training and preparation of the teachers or facilitators of the mindfulness program (Burke, 2010; Carsley et al., 2018; Emerson et al., 2019; Saunders & Kober, 2020). School-based mindfulness programs are typically led by either outside facilitators or trained classroom teachers. Some research has suggested that trained teachers elicit more positive outcomes than outside facilitators (Carsley et al., 2018). This may be because teachers have extensive interaction with the children outside the program and may be more likely to incorporate or reinforce elements of the mindfulness program day to day (Britton et al., 2014; Carsley et al., 2018). Other research has shown that mindfulness programs have a stronger effect with more minutes of training and more home practice, which suggests that increased teacher-initiated practice may improve program outcomes (Chadwick & Gelbar, 2016; Zenner et al., 2014). However, much of the outcome research for school-based mindfulness programs using outside facilitators does not document the degree of classroom teacher involvement in the program or their implementation of mindfulness practices outside of the formal program.

In an examination of implementation factors in the delivery of school-based mindfulness programs, Dariotis et al. (2017) identified student and teacher “buy-in” as an important consideration for programs. Teachers and students in their study expressed a desire for integration of mindfulness strategies during aspects of their regular school day, suggesting that this may influence teacher and student engagement. Although research on school-based mindfulness programs frequently includes information on the training of the facilitators, it generally neglects any measurement of day-to-day implementation of mindfulness practices beyond the formal program sessions.

In this study, we evaluated the outcomes of an 8-week (16 session) school-based mindfulness program for children in grades K – 2. All students participated in a mindfulness program facilitated by an outside instructor as part of their regular classroom schedule. We incorporated several unique methodological elements to address some of the limitations of previous research. Specifically, we included direct assessment of implementation fidelity pertaining to the structural components of the program (e.g., adherence, dosage, responsiveness; see Gould et al., 2016). We also incorporated measures of classroom teacher implementation of mindfulness strategies outside of the formal program and student engagement during the sessions.

Method

Design

The present study evaluates outcomes for a school-based mindfulness program implemented in a public elementary school in northeastern Pennsylvania. We used a quasi-experimental pretest-posttest design with an immediate intervention condition (group 1) and a delayed (4 weeks) intervention condition (group 2). The primary outcome variables were classroom teacher ratings of the student’s prosocial behavior and behavioral/emotional difficulties.

Schoolwide Demographics

Approximately 94% of students in the selected elementary school receive free or reduced lunch and 10% are English-language learners. Nearly 77% of enrolled students identify as Hispanic, 13% identify as African American, 5% identify as White, 3% identify as Multi-Racial, and 1% identify as Asian.

Sample Demographics

Across all classrooms, 136 children participated in the mindfulness program. Parents or guardians for 30 children chose to opt-out (N = 13) or did not adequately complete the required forms (N = 17). Data for those children were not included in our analyses, even though the children participated in the mindfulness program. The profile of the excluded cases was not significantly different from included cases across race, χ2 (2, N = 117)=1.35, p = 0.508 or sex, χ2 (1, N = 134)=0.12, p = 0.737. After excluding cases, teacher ratings were available for a total of 106 students, but there were some missing data at each of the time points. Students’ date of birth, gender, and race/ethnicity were provided by the school. Data provided by the school did not allow for indication of gender other than male or female and did not include a multiracial category. Once student demographics were matched with teacher ratings, all identifying information was removed from the dataset. Student ages ranged from five years old to nine years old (M = 6.68, SD = 0.89). Approximately 45% of students were identified as girls (N = 47) and 55% were identified as boys (N = 58). Among the children for whom race and ethnicity were provided (N = 90), the sample was generally representative of the school as a whole [Hispanic/Latino (78%), Black/African-American (17%), White/Caucasian (6%)].

Classrooms

All eight K – 2 classrooms (2 kindergarten, 3 first grade, 3 second grade) in the school participated in the mindfulness program. Classroom teachers were encouraged but not required to participate in mindfulness sessions. All students in the school also participated in a leadership and empowerment program for the 2019-2020 school year (www.leaderinme.org). Most of the classroom teachers had little prior experience with mindfulness or meditation. Only 2 reported receiving any formal training in yoga, meditation, or other mindfulness practices. Several teachers reported engaging in mindfulness practices on their own at least occasionally, including yoga (N = 3), meditation (N = 3), and mindful activities (e.g., mindful walking, mindful eating; N = 4). Using a 5-point scale, all 8 teachers reported that they were either moderately (N = 3), very (N = 2), or extremely (N = 3) interested in learning mindfulness techniques to use in their classrooms. To recognize the value of teachers’ time, we provided gift cards ($75) to teachers for completing rating scales. Classroom supplies were also donated by a local organization for all participating classrooms (valued at approximately $75).

Mindfulness Instructor

The same instructor taught all mindfulness sessions at the elementary school. The mindfulness instructor has been teaching mindfulness programs for 4 years and has completed extensive training as a requirement for participating in the delivery of the school-based program. This training included 200+ hours of yoga teacher training program, a 14-hour trauma-informed training program, and two 6-week online courses through Mindful Schools (Mindfulness Fundamentals, Mindful Educator Essentials).

Mindfulness Curriculum

Session content for the mindfulness curriculum is presented in Table 1. The curriculum used in this study was developed over the course of several years using two established mindfulness curricula: Mindful Schools (mindfulschools.org) and MindUp™ (mindup.org). Research on the Mindful Schools curriculum has documented positive effects on children’s depression and teacher ratings of students’ attention, self-control, and prosocial behavior (Black & Fernando, 2014; Liehr & Diaz, 2010). The MindUp program has been associated with reductions in behavioral problems and improvements in social and emotional competence, behavioral regulation, adaptive skills, and executive functioning (Crooks et al., 2020; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015; Schonert-Reichl & Lawlor, 2010). For the curriculum adapted for the current study, lessons 1-3, 6-10, 12, 15 and 16 are derived from the Mindful Schools curriculum, which was developed for grades K-5. Lessons 3, 4, and 14 are derived from the MindUp™ curriculum, which was developed for grades K-2. Two new lessons were developed by the second author’s organization in response to an emerging need in a large number of classrooms for instruction about the mindfulness of change (Lesson 11) and kind words (Lesson 13). These lessons were also designed for grades K-2. The conceptual basis of the curriculum is aligned with the framework suggested by Flook et al. (2015), in which training in mindfulness practices improves attention and self-regulatory functions, which then facilitate the development of prosocial behavior and a reduction in problem behavior.

Table 1.

Mindfulness program lessons

| Lesson # | Curriculum Source | Lesson Title/Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Lesson 1 | Mindful Schools | Mindfulness Introduction |

| Lesson 2 | Mindful Schools | Breath |

| Lesson 3 | Mindful Schools | Heartfulness & Kind Thoughts |

| Lesson 4 | Mind-Up | The Brain |

| Lesson 5 | Mind-Up | The Brain & Emotions |

| Lesson 6 | Mindful Schools | Generosity & Kind Actions |

| Lesson 7 | Mindful Schools | Thoughts |

| Lesson 8 | Mindful Schools | Gratitude |

| Lesson 9 | Mindful Schools | Kind & Caring On the Playground |

| Lesson 10 | Mindful Schools | Emotions |

| Lesson 11 | Shanthi Project | Change |

| Lesson 12 | Mindful Schools | Mindful Test Taking |

| Lesson 13 | Shanthi Project | Mindful Communication/Kind Words |

| Lesson 14 | Mind-Up | Taking Another’s Point of View |

| Lesson 15 | Mindful Schools | Mindful Eating |

| Lesson 16 | Mindful Schools | Ending Review |

Measures

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The SDQ (Goodman, 1997) is a 25-item rating scale completed by classroom teachers to measure student behavior. SDQ items are scored on a 3-point response scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = certainly true). The SDQ consists of five subscales (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, prosocial behavior), each with scores ranging from zero to ten. All items are coded such that higher scores indicate more of the target behavior. In a large scale factor analytic study, Goodman and colleagues (2010) recommend using broader internalizing and externalizing subscales for analyses of low-risk samples rather than the original subscales. Therefore, for the purposes of this study, we restricted analyses to internalizing (emotional and peer subscales) and externalizing (hyperactivity and conduct subscales) behaviors in addition to the prosocial subscale. We computed Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each subscale score at each time point. Reliability coefficients for the internalizing (0.71 < α <0.81), externalizing, (0.90 < α <0.93), and prosocial behavior (0.87 < α <0.90) were good to excellent at each time point.

Session Engagement

To examine the degree to which classroom teachers and students actively participated in the program, the mindfulness instructor completed two single-item measures to evaluate student engagement and teacher engagement during mindfulness sessions. For teacher engagement, the instructor indicated whether the classroom teacher (a) actively participated for the whole mindfulness session, (b) actively participated for part of the session, (c) did not participate, (d) was not present during the session, or (e) was present but disruptive during the session. We estimated the degree of overall teacher engagement by computing the proportion of sessions in which the teacher actively participated in part or all of a session. Overall, teachers were generally engaged with the program, actively participating in nearly two-thirds of the 16 sessions on average (M = 10.38, SD = 4.03). However, there was considerable variability in teachers’ level of engagement with the mindfulness sessions. While four teachers actively participated in at least 75% of the sessions, two teachers actively participated in less than a third of the sessions.

For student engagement, the mindfulness instructor rated the extent to which students, as a group, were actively involved in the day’s lesson on a 5-point scale (1 = not engaged at all; 5 = very engaged). Consistent with previous studies, we estimated the level of student engagement by computing the mean engagement score across all 16 sessions (Frank et al., 2014). Students in this sample were highly engaged in the program according to mindfulness instructor ratings. The mean student engagement rating for each classroom ranged from 3.86 (SD = 0.70) to 4.87 (SD = 0.35) with a mean engagement score of 4.35 across all classrooms (SD = 0.40).

Teacher Implementation

To better understand the degree to which teachers found value in the mindfulness program and subsequently integrated it into their day-to-day classroom activities, we incorporated several brief assessments of teachers’ use of mindfulness practices with their students outside of the sessions. Specifically, at two points during the program (after 5 sessions, after 10 sessions) and two points after the program (5 weeks, 10 weeks), teachers completed a brief online survey that asked them to report whether or not they had used any of six different mindfulness practices (e.g., mindful breathing, practicing gratitude) during the preceding week. We estimated overall teacher implementation by computing the mean number of possible practices used across all time samples. Teachers in the delayed intervention group only completed the teacher involvement measure once after the program. The final scheduled assessment occurred after the schools were closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implementation Fidelity

The mindfulness instructor completed an implementation fidelity checklist after every lesson. The measure includes six forced-choice questions that evaluate the degree to which each given session was delivered as intended, and included core curricula and process components (e.g., review of past content, mindful listening exercise, seated mindfulness practice). Core components were derived from pilot testing, curricular review, and collaboration with two experienced mindfulness instructors. The resulting fidelity checklist was revised based on preliminary pilot testing with 4 mindfulness instructors across 53 sessions and is intended to align with several of Gould et al.’s (2016) dimensions of fidelity. For example, to address the extent to which the curriculum’s core components were implemented as designed (i.e., adherence), instructors answered a series of yes/no questions about core content immediately after each session (e.g., Did you complete a mindful listening exercise with the singing bowl?). Of the total of 128 lessons taught across all classrooms, we found that 96% (N = 123) included at least five of the core content areas and approximately 85% included all six content areas. Dosage was reflected in both the percent of lessons received and the total duration of the program (i.e., 320 minutes). To assess the extent to which participants were engaged in the program (i.e., responsiveness), mindfulness instructors provided ratings of student engagement immediately after each session (i.e., “As a whole, how actively involved were the students in the lesson today?”).

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the first author’s institutional review board. Parents of children in the kindergarten, first, and second grade were informed by the school about the inclusion of a mindfulness program as part of the school curriculum independent of the current research. Participation in the research study involved providing informed consent for the inclusion of teacher-ratings of their child’s behavior. Parents received a letter explaining the nature of the research and could choose to opt-out of including teacher-ratings of their child for the research study. In those cases, the child still participated in the mindfulness program as part of the school curriculum.

One week prior to the start of the program, the mindfulness instructor and a research consultant met with the classroom teachers participating in the present study. A survey of prior experience with mindfulness was distributed and reviewed, as were completion instructions for the SDQ. In addition, a timeline for teacher involvement surveys and gift card incentives for completion of the assessments were reviewed. The curriculum was also reviewed with the teachers, as was the importance of classroom teacher engagement to the success of the program. The mindfulness program was delivered across eight classrooms, twice a week, for a duration of eight weeks. Sessions were approximately 20 minutes in length.

Eight elementary school classrooms were randomly assigned in blocks (i.e., by grade) to be in the immediate or delayed program group. All 8 classroom teachers completed the SDQ before the mindfulness program began in mid-September. These ratings served as the pre-program assessment for Group 1 (immediate) and the initial baseline assessment for Group 2 (delayed). Four of the classrooms (Group 1) began the mindfulness program immediately. They received the SDQ a second time upon completion of the 16-session curriculum in mid-November (post-program). The remaining four classrooms (Group 2) began the mindfulness program four weeks later than Group 1, serving as a delayed intervention group. Classroom teachers from Group 2 completed the SDQ an additional time pre-program (mid-October) and near the end of December (post-program).

Results

Pre-Program Differences

Because we were only able to randomly assign blocks (i.e., classrooms) and not children to conditions, we conducted a series of analyses to evaluate whether the two intervention groups differed at the start of the mindfulness program. We used a 2-level linear mixed model analysis with classroom teacher as a level 2 random effect for pre-test scores on the primary outcome measures. The two intervention groups were not significantly different at pre-test on SDQ prosocial, t(6.25) = −0.47, p = 0.656, internalizing, t(6.41) = −0.74, p = 0.486, or externalizing scores t(6.35) = 0.32, p = 0.759. The groups also did not differ in the sex, χ2 (1, N =105) = 0.12, p = 0.914, or race/ethnicity, χ2(2, N = 90) = 0.99, p = 0.611. With regard to age, the children in Group 2 (delayed) were slightly older, F(1, 101) = 6.33, p = 0.013. However, this difference is likely due to the fact that an odd number (i.e., three) of 1st and 2nd grade classrooms resulted in more 2nd grade students in one group than the other.

Establishing a Baseline

To help rule out that any changes in student behavior during the intervention period were due to factors outside of the program (e.g., school-wide leadership program), we evaluated if SDQ scores changed over the four-week period preceding the program for Group 2 using linear mixed modeling with classroom teacher as a level-3 random factor and individual student as a level-2 random factor. Results indicated that there were no significant differences in internalizing scores, F(1, 49.48) = 0.11, p = 0.737, externalizing behavior scores, F(1, 49.09) = 0.49, p = 0.486, or prosocial behavior scores, F(1, 49.50) = 0.07, p = 0.794, over the baseline period.

Evaluation of Outcomes

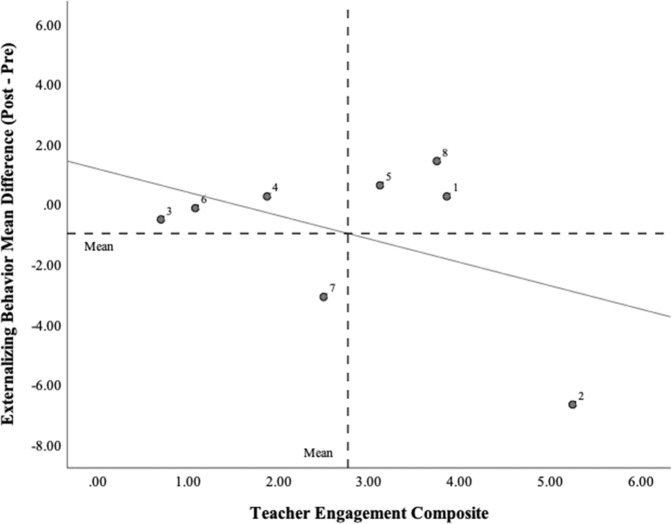

The delayed and immediate intervention groups used the same curriculum with the same mindfulness instructor. Therefore, we would not expect to see a group by time interaction. If there were a significant interaction, subsequent analyses would need to account for group status in addition to teacher and student level explanatory variables. To examine this question, we conducted 3-level linear mixed model analyses for each of the primary outcome variables. In these analyses, repeated measurements (level 1) were nested within individuals (level 2) who in turn were nested within classroom teacher (level 3). We estimated the variance of random intercepts (and not slopes) at levels 2 and 3. We treated time and intervention group as fixed factors, and examined the effect of the time by group interaction in this model. Results indicated that there was no group by time interaction for prosocial behavior, F(1, 95.84) = 0.12, p = 0.734, internalizing behaviors, F(1, 85.46) = 1.39, p = 0.242, or externalizing behaviors, F(1, 92.87) = 2.26, p = 0.136. Because there did not appear to be any group by time interactions, we aggregated the delayed and immediate intervention groups for subsequent analyses. Figure 1 presents the estimated marginal means for pre-program and post-program on each of the outcomes. Collapsing across group status, teachers’ SDQ ratings indicated significant improvements on two of the three primary outcomes. Specifically, from pre-program to post-program, teacher ratings of students’ prosocial behavior increased, F(1,95.84) = 22.43, p < 0.001, and ratings of externalizing behaviors decreased, F(1,92.87) = 6.16, p = 0.015. There was not a significant change in teacher ratings of students’ internalizing behavior, F(1,85.46) = 1.73, p = 0.192.

Fig. 1.

Pre-post program changes on teacher ratings of children’s behavior. Note. Bars represent standard errors

Potential Moderators

To examine whether program outcomes differed according to various student characteristics, we conducted a series of linear mixed models as described above, replacing group status with specific student characteristics to examine whether the pattern of pre-post differences varied across sex, race, or grade. For comparisons of race, we included only children identified as Hispanic/Latino and Black/African-American due to the insufficient sample size for the other racial and ethnic categories. There were no significant sex by time interactions for prosocial behavior, F(1, 97.25) = 0.37, p = 0.546, internalizing problems, F(1, 86.17) = 0.04, p = 0.843, or externalizing behavior, F(1, 93.78) = 0.23, p = 0.634. There were also no race by time interactions for externalizing problems, F(1, 79.42) = 1.97, p = 0.164, internalizing problems, F(1, 76.76) = 0.01, p = 0.908, or prosocial behavior, F(1, 80.63) = 1.66, p = 0.202. These results suggest that the pattern of changes from pre to post-program were comparable across student sex and race/ethnicity. There was, however, a significant grade by time interaction for externalizing behavior, F(2, 91.75) = 5.28, p = 0.007. Teacher ratings of student externalizing behavior decreased in grade 1 but showed little change in kindergarten and 2nd grade.

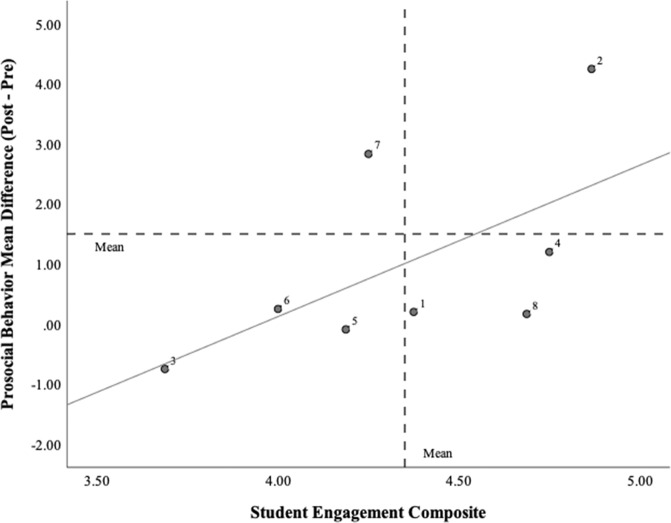

An examination of classroom by classroom changes for internalizing and externalizing outcome measures indicated that the overall pattern of scores was consistently different for one classroom. In general, classroom #8 (grade 2) showed increases in externalizing and internalizing scores, while all of the other classrooms showed either significant decreases or non-significant decreases in these outcomes. To examine the impact of this one classroom, we re-ran linear mixed models described above for each of the three outcome variables with classroom #8 removed. With one exception, the magnitude of the changes from pre-program to post-program were greater when classroom #8 was removed, but the overall pattern of changes generally remained consistent for each of the outcome measures. However, in the analysis of grade by time interactions, the removal of classroom #8 resulted in a more coherent pattern of results. Specifically, while internalizing and externalizing scores decreased for grades 1 and 2, there was little change for the kindergarten classrooms (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Changes in SDQ externalizing problems by grade (classroom # 8 removed)

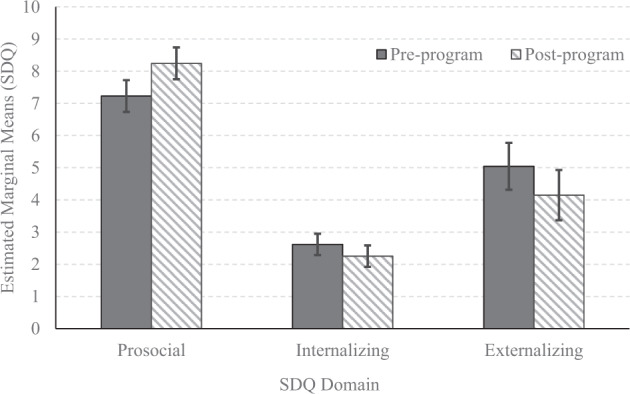

Classroom Teacher Engagement

All sessions were conducted by a trained mindfulness instructor during the regular school schedule. Classroom teachers were invited to participate in the sessions along with the students and were encouraged to use mindfulness practices from the program outside of the sessions. As described above, we recorded the proportion of sessions that classroom teachers actively participated in the mindfulness sessions (i.e., session engagement) and the mean number of mindfulness practices they had engaged in at several points during and after the program (i.e., teacher implementation). A total engagement composite was computed as the product of session engagement and implementation scores, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of overall engagement with the program. Because of the relatively small number of classrooms, we examined the potential role of teacher engagement in the program by plotting the teacher engagement composite by pre-post changes on each of the outcome measures. Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between teacher engagement across classrooms and program changes for externalizing behavior (see Supplementary Information for additional figures). Overall, there appears to be a modest tendency for greater teacher engagement to be associated with increases in prosocial behavior (r = 0.56) and decreases in externalizing behavior (r = −0.45). The pattern of scores suggests no relationship for internalizing behavior (r = 0.08). Because these correlations are based on a small sample of classes, these relationships should be interpreted as primarily descriptive or exploratory.

Fig. 3.

Change in externalizing behavior by teachers’ engagement by classroom

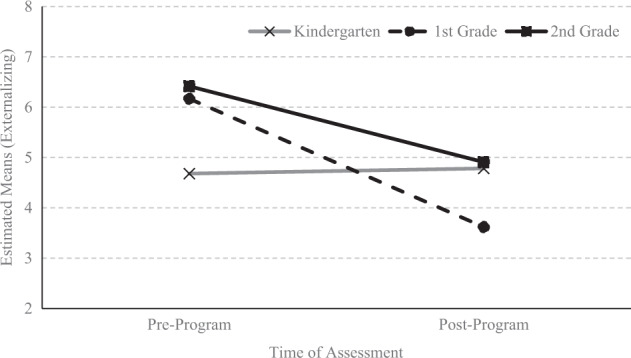

Student Engagement

As mentioned previously, student engagement in the mindfulness program was estimated using a 5-point scale completed by the mindfulness instructor immediately after each session. We computed a composite student engagement score for each classroom by getting mean ratings across all 16 sessions for that classroom. As we did for teacher engagement, we examined the potential role of student engagement in the program by plotting a student engagement composite by pre-post changes on each of the outcome measures. Results suggested that outcomes tended to be more positive for classrooms in which students were perceived to be more engaged in the sessions. Figure 4 displays the relationship for prosocial behaviors. Based on the small sample of classes, higher student engagement was generally associated with higher prosocial behavior (r = 0.60) and lower externalizing behavior (r = −0.30), but not clearly related to internalizing (r = 0.07) (see Supplementary Information for additional figures).

Fig. 4.

Change in prosocial behavior by students’ session engagement by classroom

Discussion

Mindfulness-based interventions target a range of core skills (e.g., self-regulation, attentional control) that are likely to impact children’s experience in a school context (Meiklejohn et al., 2012; Zenner et al., 2014). Consistent with prior research on school-based mindfulness interventions, we found positive but small to moderate effects on teacher ratings for both positive and negative behaviors (Carsley et al., 2018; Zoogman et al., 2015). Specifically, we found a significant decrease in externalizing behaviors (hyperactivity and conduct problems) and an increase in prosocial behaviors from pre-program to post-program. In general, we did not find significant program effects for internalizing behaviors. Given the design of this study, we are not able to distinguish whether the program is less effective for internalizing outcomes or whether the source of measurement (i.e., teacher ratings) limits the ability to detect changes. In comparison to prosocial and externalizing behaviors, internalizing behaviors are less visible to an outside observer. These results replicate those of Viglas and Perlman (2018), who used a similar curriculum, and add to the emerging literature that documents the potential for mindfulness based interventions to reduce disruptive behaviors and increase prosocial behaviors (Meiklejohn et al., 2012; Zenner et al., 2014). Like Britton et al. (2014), we implemented a program for all children in the selected grades rather than identifying a subset, which promotes greater generalizability in conclusions and minimizes the challenges of pulling students out of other desirable activities since it is built into the curriculum (Dariotis et al., 2017).

Overall, program effects were relatively consistent across student characteristics, with similar patterns of change across sex and race/ethnicity (Zoogman et al., 2015). However, there were potentially important differences by grade level. Across outcome measures, the changes were most pronounced in first grade classes, with little change in kindergarten classrooms. Outcomes for 2nd grade classrooms generally paralleled the positive changes in 1st grade classrooms, with the magnitude of the changes being affected considerably by one classroom that showed consistently different patterns of scores.

The failure to find positive changes in kindergarten classes was surprising. Some researchers have argued that mindfulness programs are particularly well-suited for pre-K and Kindergarten children (Moreno, 2017). Accordingly, several studies have documented positive outcomes of school-based mindfulness interventions in very young children (Flook et al., 2015; Thierry et al., 2016; Viglas & Perlman, 2018). However, direct comparisons are difficult because some of these studies (Flook et al., 2015; Thierry et al., 2016) were implemented by the classroom teacher, used a different mindfulness curriculum, included different outcome measures, or were implemented over a longer period of time. Viglas and Perlman (2018), however, found significant improvements in prosocial behavior and hyperactivity among this age group using the same outcome measure (i.e., the SDQ) and a variation of the same curriculum used in the current study (i.e., Mindful Schools). Their results suggest that the failure to find significant changes among the kindergarten classrooms in the present study is not necessarily attributable simply to curricular differences or program duration. It may be that there are other variables that may moderate the effects of mindfulness programs with very young children. For instance, variations in classroom teacher characteristics (e.g., program “buy-in”), school structures (e.g., half-day vs. full day kindergarten), or contextual influences (e.g., facilitator-teacher communication) may explain why a similar program might have different effects across studies (Dariotis et al., 2017). Future research should supplement measures of program outcomes with information on the extent and ways in which mindfulness practices are integrated into the classroom outside of the formal program sessions.

In the present study, we attempted to address some of the common methodological limitations in school-based mindfulness programs. For instance, we included measures of intervention fidelity to document the extent to which the program was implemented consistently and as intended. We had evidence that the program was delivered with high fidelity along several important dimensions, including adherence, dosage, and responsiveness (Gould et al., 2016). For instance, all sessions were led by the same highly-trained program facilitator to control for variations in the delivery of the program. The facilitator documented very high levels of implementation of core program content across all classrooms. It is important to note, however, that the fidelity measures were completed by the mindfulness instructors. Ideally, future research should also incorporate ratings by outside observers to assess for potential bias. However, this concern is mitigated somewhat by the fact that the majority of the fidelity checklist contained simple yes/no statements about whether specific content was covered. These kinds of statements are less likely to be subject to interpretation. We also addressed other dimensions of fidelity (i.e., responsiveness) by measuring classroom teacher and student engagement in each session of the program. With regard to students’ responsiveness, the facilitator rated the level of engagement in the lessons as consistently high across the program. Although our data are based on a small sample of classrooms, students’ and teachers’ engagement in the program appeared to be associated with more positive outcomes. More rigorous measurement of engagement is necessary to draw more definitive conclusions, but this finding represents an important consideration for future research on school-based mindfulness programs. While there has been a call for more effective documentation of intervention fidelity for mindfulness programs (Gould et al., 2016; Kechter et al., 2019), there has been little systematic investigation of the ways in which these programs are integrated into the classroom culture outside of the formal program. Gould et al. (2016) argues that outside mindfulness practice may be a proximal predictor of program outcomes and is a potentially important aspect of the responsiveness dimension of implementation fidelity. Although studies of adult mindfulness programs often include measures of outside practice (Kechter et al., 2019), this information is often lacking in research on school-based mindfulness programs (Gould et al., 2016). One notable exception was Kuyken et al. (2013), who found that the extent of adolescents’ post-program mindfulness practice was associated with more positive outcomes at post-program and at a 3 month follow-up. In the current study, we included measures of teachers’ use of mindfulness practice both during and after the program.

Limitations

Although the inclusion of specific measures of student and teacher responsiveness to the intervention represents a strength of the current study, each of these measures was provided by a single source. Specifically, the mindfulness instructor provided all ratings of students’ and classroom teachers’ engagement during mindfulness sessions. To account for potential rater bias, future research should consider also using independent observers to measure child and teacher responsiveness. Aside from the source of the fidelity measurement, there were also important limitations in the way that we operationalized teachers’ engagement. For “in-session” engagement, we used the proportion of sessions in which teachers actively participated. However, we know little about the specific nature of teachers’ involvement. Teachers who participated in more sessions may have had a genuine interest in learning mindfulness practices or they may simply have been more concerned with monitoring and correcting children’s behavior. On the other hand, teachers may have had a genuine interest in learning mindfulness practices, but were unable to participate actively due to workload or administrative challenges. Our measure of teacher involvement outside of the program sessions may also be incomplete. Teachers’ willingness to implement practices outside of the sessions should be a good indicator of investment in the program. However, we estimated this involvement by measuring the number of practices implemented in a given week across a small number of time samples. Measuring the number of practices at a few time points may not adequately capture the degree of investment in the program. For instance, estimating teacher involvement in this way would not capture a teacher who consistently uses one or two practices very effectively.

Future studies should build on the current research by more precisely operationalizing the nature of teachers’ engagement during and outside of the program sessions. For in-session engagement, teacher engagement could be deliberately built into specific sessions and evaluated as a program component (e.g., standard curriculum vs. teacher-engaged curriculum). Conceptualizing teacher engagement as a program component would reduce some of the error variance associated with estimating engagement based on voluntary participation as was done in the current study. Outcome studies could then employ a dismantling strategy to better understand the role that active teacher engagement plays in program outcomes (Stein & Witkiewitz, 2020). With regard to responsiveness outside of formal sessions, future research should assess not just the number of mindfulness practices implemented, but also the frequency and context for these practices. Weekly journals or an ecological momentary assessment approach (e.g., Ruscio et al., 2016) might better capture the ways in which mindfulness practices have or have not become part of the classroom culture beyond the mindfulness program itself. Further, our study is limited in its ability to account for cultural, organizational, and institutional factors that impact program engagement and curricular accessibility. For example, the broader school population in this study included 10% English-language learners, which may serve as a barrier to engagement. In the current study, we did not collect information on English language proficiency. Potential barriers to engagement like this should be considered in future implementations of programs in order to ensure programs are effectively targeted and delivered (Watson-Singleton et al., 2019).

Another limitation of the current study is that outcomes were measured through a single source, teacher ratings of behavior. Although the results are consistent with prior research using these ratings, the conclusions would be strengthened by the inclusion of performance-based measures of anticipated outcomes, such as self-regulation skills. Previous research has supplemented observer or teacher ratings with measures such as the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders Task (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016; Viglas & Perlman, 2018) or the Flanker Fish task (Flook et al., 2015).

Finally, as has been well-documented in the mindfulness literature, the results of the current study are limited by the lack of an active control group. Because the program was implemented as part of the regular curriculum, inclusion of an active control group was not feasible. Instead, we used a delayed-intervention condition as the control group to assess the potential for natural changes over time or artifacts of repeated measurements. Because the delayed intervention group did not change over the 4-week baseline period, we are more confident that the subsequent changes were due to some aspect of the program. The lack of a change over the baseline period also helps to rule out the possibility that outcomes were influenced by other curricular or co-curricular elements in the school (e.g., leadership program). However, we are unable to determine whether the mindfulness program was effective because of the mindfulness practices per se or because of expectancy effects or other nonspecific mechanisms (e.g., instructor rapport).

In conclusion, results of the present study add to the growing knowledge base on the positive effects of school-based mindfulness interventions and point to several areas in need of more rigorous inquiry. In particular, as the evidence base on school-based mindfulness interventions grows, our results suggest that, in addition to well-documented issues related to outcome measures and control groups, future research should focus on the extent to which students and teachers are engaged with mindfulness programs both during the program itself and in their day to day functioning. Ideally, the effects of any mindfulness program will be reflected not just in changes on targeted outcomes, but also in the extent to which mindfulness practices become integrated into the classroom climate.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Brooke Kohler for her feedback during the development of teacher engagement and fidelity measures.

Funding

Portions of this project were supported by funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the St.Luke’s University Health Network (Community Health).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

M.S. has received consultant honoraria from Shanthi Project. D.V. is the founder and former Executive Director of Shanthi Project and is currently receiving compensation in the form of a monthly stipend as a research consultant. T.M., B.B., and S.C. declare they have no financial interests.

Ethical Approval

All participants were treated in accordance with the APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. The study was approved in accord with the Muhlenberg College Institutional Review Board’s Policy and Procedures for Research Involving Human Subjects (8/30/19; #1902).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Mark J. Sciutto, Denise A. Veres

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10826-021-01955-x.

References

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(12):1849–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakosh LS, Snow RM, Tobias JM, Houlihan JL, Barbosa-Leiker C. Maximizing mindful learning: mindful awareness intervention improves elementary school students’ quarterly grades. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):59–67. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0387-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin J, Hutchins TL, Patterson F. Mindfulness meditation may lessen anxiety, promote social skills, and improve academic performance among adolescents with learning disabilities. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2008;13(1):34–45. doi: 10.1177/1533210107311624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, Segal ZV, Abbey S, Speca M, Velting D, Devins G. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;11(3):230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black, D. S. (2015). Mindfulness training for children and adolescents: a state-of-the-science review. In K. W. Brown, J. D. Creswell, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness: theory, research, and practice. (2015-10563-016; pp. 283–310). The Guilford Press.

- Black DS, Fernando R. Mindfulness training and classroom behavior among lower-income and ethnic minority elementary school children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23(7):1242–1246. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9784-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton WB, Lepp NE, Niles HF, Rocha T, Fisher NE, Gold JS. A randomized controlled pilot trial of classroom-based mindfulness meditation compared to an active control condition in sixth-grade children. Journal of School Psychology. 2014;52(3):263–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CA. Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: a preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(2):133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9282-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carsley D, Khoury B, Heath NL. Effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for mental health in schools: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2018;9(3):693–707. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0839-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick J, Gelbar NW. Mindfulness for children in public schools: current research and developmental issues to consider. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 2016;4(2):106–112. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2015.1130583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KA, Hartman M. Mechanisms of action in the inverse relationship between mindfulness and psychological distress. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2008;13(2):79–91. doi: 10.1177/1533210108316307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks CV, Bax K, Delaney A, Kim H, Shokoohi M. Impact of MindUP among young children: improvements in behavioral problems, adaptive skills, and executive functioning. Mindfulness. 2020;11(10):2433–2444. doi: 10.1007/s12671-020-01460-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dariotis JK, Mirabal‐Beltran R, Cluxton‐Keller F, Gould LF, Greenberg MT, Mendelson T. A qualitative exploration of implementation factors in a school‐based mindfulness and yoga program: lessons learned from students and teachers. Psychology in the Schools. 2017;54(1):53–69. doi: 10.1002/pits.21979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Kaszniak AW. Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist. 2015;70(7):581–592. doi: 10.1037/a0039512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning DL, Griffiths K, Kuyken W, Crane C, Foulkes L, Parker J, Dalgleish T. Research review: the effects of mindfulness‐based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents—a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2019;60(3):244–258. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund K, O’Malley M, Meyer L. Gauging mindfulness in children and youth: school‐based applications. Psychology in the Schools. 2017;54(1):101–114. doi: 10.1002/pits.21983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, L.-M., de Diaz, N.N., Sherwood, A., Waters, A., & Farrell, L. (2019). Mindfulness interventions in schools: Integrity and feasibility of implementation: International Journal of Behavioral Development. 10.1177/0165025419866906

- Felver JC, Jennings PA. Applications of mindfulness-based interventions in school settings: an introduction. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0478-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flook L, Goldberg SB, Pinger L, Davidson RJ. Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based kindness curriculum. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51(1):44–51. doi: 10.1037/a0038256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JL, Bose B, Schrobenhauser-Clonan A. Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health, stress coping strategies, and attitudes toward violence: findings from a high-risk sample. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2014;30(1):29–49. doi: 10.1080/15377903.2013.863259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Kim JJ, Jin J, Chen G, Bear L, Lau AS. A randomized trial evaluating school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth: exploring mediators and moderators of intervention effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2019;47(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Lamping DL, Ploubidis GB. When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): data from British parents, teachers and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38(8):1179–1191. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MS, Madni LA, Semple RJ. Measuring mindfulness in youth: review of current assessments, challenges, and future directions. Mindfulness. 2017;8(6):1409–1420. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0719-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould LF, Dariotis JK, Greenberg MT, Mendelson T. Assessing fidelity of implementation (FOI) for school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions: a systematic review. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):5–33. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0395-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Harris AR. Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: current state of research. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(2):161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00215.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce A, Etty-Leal J, Zazryn T, Hamilton A, Hassed C. Exploring a mindfulness meditation program on the mental health of upper primary children: a pilot study. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2010;3(2):17–25. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2010.9715677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat‐Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kallapiran K, Koo S, Kirubakaran R, Hancock K. Review: effectiveness of mindfulness in improving mental health symptoms of children and adolescents: a meta‐analysis. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2015;20(4):182–194. doi: 10.1111/camh.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kechter A, Amaro H, Black DS. Reporting of treatment fidelity in mindfulness-based intervention trials: a review and new tool using NIH Behavior Change Consortium Guidelines. Mindfulness. 2019;10(2):215–233. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Weare K, Ukoumunne OC, Vicary R, Motton N, Burnett R, Cullen C, Hennelly S, Huppert F. Effectiveness of the mindfulness in schools programme: non-randomised controlled feasibility study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;203(2):126–131. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr P, Diaz N. A pilot study examining the effect of mindfulness on depression and anxiety for minority children. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;24(1):69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiklejohn J, Phillips C, Freedman ML, Griffin ML, Biegel G, Roach A, Frank J, Burke C, Pinger L, Soloway G, Isberg R, Sibinga E, Grossman L, Saltzman A. Integrating mindfulness training into K-12 education: fostering the resilience of teachers and students. Mindfulness. 2012;3(4):291–307. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0094-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno AJ. A theoretically and ethically grounded approach to mindfulness practices in the primary grades. Childhood Education. 2017;93(2):100–108. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2017.1300487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann-Tynan J, Vigna AB, Weymouth LA, Gerstein ED, Burnson C, Zabransky M, Lee P, Zahn-Waxler C. A pilot study of contemplative practices with economically disadvantaged preschoolers: children’s empathic and self-regulatory behaviors. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):46–58. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0426-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AC, Muench C, Brede E, MacIntyre J, Waters AJ. Administration and assessment of brief mindfulness practice in the field: a feasibility study using ecological momentary assessment. Mindfulness. 2016;7(4):988–999. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0538-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, D., & Kober, H. (2020). Mindfulness-based intervention development for children and adolescents. Mindfulness. 10.1007/s12671-020-01360-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schonert-Reichl KA, Lawlor MS. The effects of a mindfulness-based education program on pre- and early adolescents’ well-being and social and emotional competence. Mindfulness. 2010;1(3):137–151. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0011-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl KA, Oberle E, Lawlor MS, Abbott D, Thomson K, Oberlander TF, Diamond A. Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51(1):52–66. doi: 10.1037/a0038454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Karazsia BT, Felver JC, Myers RE, Nugent K. Effects of Samatha meditation on active academic engagement and math performance of students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):68–75. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0424-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, E., & Witkiewitz, K. (2020). Dismantling mindfulness-based programs: a systematic review to identify active components of treatment. Mindfulness. 10.1007/s12671-020-01444-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thierry KL, Bryant HL, Nobles SS, Norris KS. Two-year impact of a mindfulness-based program on preschoolers’ self-regulation and academic performance. Early Education and Development. 2016;27(6):805–821. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2016.1141616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam NT, van Vugt MK, Vago DR, Schmalzl L, Saron CD, Olendzki A, Meissner T, Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Gorchov J, Fox KCR, Field BA, Britton WB, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Meyer DE. Mind the hype: a critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2018;13(1):36–61. doi: 10.1177/1745691617709589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viglas M, Perlman M. Effects of a mindfulness-based program on young children’s self-regulation, prosocial behavior and hyperactivity. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018;27(4):1150–1161. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0971-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson-Singleton NN, Black AR, Spivey BN. Recommendations for a culturally-responsive mindfulness-based intervention for African Americans. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2019;34:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenner C, Herrnleben-Kurz S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based interventions in schools-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:1–20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoogman S, Goldberg SB, Hoyt WT, Miller L. Mindfulness interventions with youth: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2015;6(2):290–302. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0260-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.