Abstract

Cysteine relays, where a protein or small molecule is transferred multiple times via transthiolation, are central to the production of biological polymers. Enzymes that utilise relay mechanisms display broad substrate specificity and are readily engineered to produce new polymers. In this review, I discuss recent advances in the discovery, engineering and biophysical characterisation of cysteine relays. I will focus on eukaryotic ubiquitin (Ub) cascades and prokaryotic polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthesis. These evolutionarily distinct processes employ similar chemistry and are readily modified for biotechnological applications. Both processes have been studied intensively for decades, yet recent studies suggest we do not fully understand their mechanistic diversity or plasticity. I will discuss the important role that activity-based probes (ABPs) and other chemical tools have had in identifying and delineating Ub cysteine-relays and the potential for ABPs to be applied to PHA synthases. Finally, I will offer a personal perspective on the potential of engineering cysteine-relays for non-native polymer production.

Keywords: Cysteine, Transthiolation, Cell signalling, polymer production

The ubiquitylation cascade is a promiscuous cysteine relay

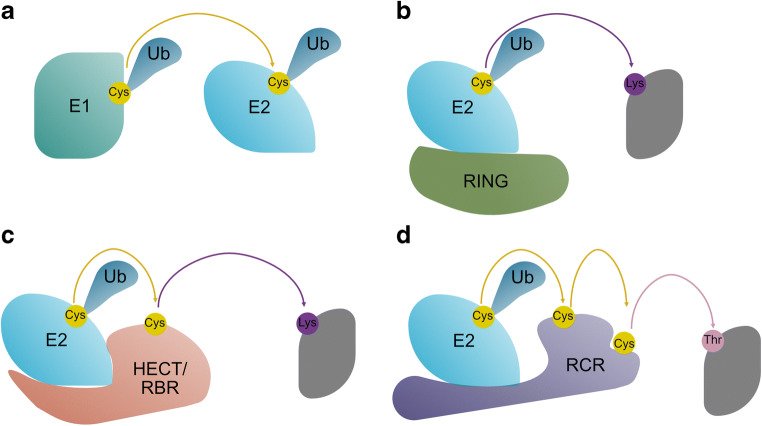

Transthiolation is the process of exchanging a thiol group from one molecule to another. In a biological context, this usually involves exchanging a molecule between cysteines or between a cysteine and a cysteine-derived molecule (such as Coenzyme A (CoA) or glutathione). Numerous unrelated biological polymers are produced as the end point of cysteine relays involving multiple sequential transthiolation events. Protein ubiquitylation is the most well characterised of these cysteine relays (Fig. 1). In the classical ubiquitylation cascade, Ub is activated by an ATP-dependent Ub activating enzyme (E1). The carboxy terminus of Ub is attached via a thioester bond to the catalytic cysteine of the E1. A ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) then binds to the E1, where its catalytic cysteine is juxtaposed with that of the E1, facilitating transthiolation (Olsen and Lima 2013). The E2 ubiquitin conjugate (E2~Ub) can then bind one of many (~ 600 in humans) RING (Really Interesting New Gene) type ubiquitin E3 ligases (E3) which allosterically activate the E2~Ub conjugate for Ub discharge to the epsilon-amino group of lysine within substrate proteins (Deshaies and Joazeiro 2009; Plechanovova et al. 2012). This ‘canonical’ pathway with Ub transfer from E1 catalytic cysteine to E2 catalytic cysteine and finally to a lysine residue within a substrate accounts for the majority of ubiquitylation events within the cell (Deshaies and Joazeiro 2009). However, over 35 years ago, it was noted that ubiquitylating enzymes are promiscuous and can utilise ‘non-native’ substrates (Rose and Warms 1983); this feature of the pathway is frequently exploited in structural and mechanistic studies (Burchak et al. 2006; Eddins et al. 2006; Plechanovova et al. 2012) (Table 1). Several Ub-like proteins with dedicated E1s and E2s have been discovered and are reviewed elsewhere (Cappadocia and Lima 2018). Of these Ub-like proteins, the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) and its associated conjugation and deconjugation machinery have proven to be the most biotechnologically tractable (Hofmann et al. 2020; Lau et al. 2018; Malakhov et al. 2004).

Fig. 1.

The ubiquitylation cascade involves multiple cysteine relays. a Ubiquitin (Ub) E1 catalyses adenylation of the Ub C-terminus. Following adenylation, the Ub C-terminus is attached via a thioester bond to the catalytic cysteine of E1. E1 then transfers Ub to the catalytic cysteine of a Ub-conjugating enzyme (E2). b E2s catalyse lysine aminolysis (transfer of Ub to the epsilon-amino group of lysine), many E2s are allosterically activated by RING domain containing Ub E3 ligases (E3s). c E2s transfer Ub to the catalytic cysteine of HECT and RBR E3s, the HECT or RBR then catalyses lysine aminolysis. d, E2s transfer Ub to the upstream catalytic cysteine of RCR E3s; Ub is subsequently intramolecularly transferred to the downstream cysteine. The downstream cysteine catalyses transfer of Ub to threonine within substrate proteins

Table 1.

The ubiquitylation cascade is a well-characterised cysteine relay. Most enzymes in the cascade are promiscuous and can transfer Ub to ‘non-native’ substrates

| Enzyme class | Native activity | Non-native activities observed or engineered in the laboratory | Key references describing non-native activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | Adenylation of the Ub carboxyl terminus. Transfer of Ub to the active site cysteine of E2s. | Transfer of Ub to the active site serine or lysine of E2s. Transfer of Ub to small molecule thiols. Transfer of chemically modified Ub to E2s. Transfer of Ub-like peptides to E2s. | (Burchak et al. 2006; Eddins et al. 2006; El Oualid et al. 2010; Mulder et al. 2016; Plechanovova et al. 2012; Rose and Warms 1983). |

| E2 | Transfer of Ub to the epsilon amino-group of lysine and the amino-terminus of proteins. Transfer of Ub to active site cysteines in HECT, RBR and RCR E3s. | Transfer of Ub to serine, threonine and hydroxylamine. Transfer of Ub-like peptides to the epsilon amino-group of lysine. Transfer of chemically modified Ub to E3s. Transfer of Ub to lysine analogues (L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid, Nα-acetyl-L-ornithine and L-homolysine). | (Hofmann et al. 2020; Liwocha et al. 2020; Mulder et al. 2016; Saha and Deshaies 2008; Wang et al. 2009; Wenzel et al. 2011). |

| HECT | Transfer of Ub to the epsilon amino group of lysine. | Transfer of Ub to serine and/or threonine. Transfer of Ub to lysine analogues (L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid, Nα-acetyl-L-ornithine and L-homolysine). | (Liwocha et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2018). |

| RBR | Transfer of Ub to the epsilon amino group of lysine and the amino terminus of proteins. | Transfer of Ub to serine and/or threonine. | (Kelsall et al. 2019). |

| RCR | Transfer of Ub to threonine. | Transfer of Ub to serine, glycerol and tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) | (Mabbitt et al. 2020; Pao et al. 2018). |

| DUB | Cleavage of isopeptide and peptide linked Ub. | Cleavage of Ub linked to serine, threonine and fluorophores. | (Dang et al. 1998; De Cesare et al. 2021). |

Apart from RING family E3s, three classes of cysteine-dependent E3 have been identified. Given the promiscuity of E2 binding and transthiolation, it is plausible that many other classes remain to be described (Ahel et al. 2020). These cysteine-dependent E3s form a thioester adduct with Ub (E3~Ub) and subsequently transfer Ub to substrate proteins. The three established classes are HECT (homologous to E6AP) (Scheffner et al. 1995), RBR (RING-Between-RING) (Marin et al. 2004; Wenzel et al. 2011) and RCR (RING-Cys-Relay) E3 ligases (Mabbitt et al. 2020; Pao et al. 2018). The HECT and RBR E3s bind E2~Ub and Ub is transferred to the active site cysteine to produce E3~Ub. Ub transfer is facilitated by cysteine proximity and does not require allosteric activation of the E2 (Dove et al. 2017; Dove et al. 2016; Kamadurai et al. 2009; Lechtenberg et al. 2016; Yuan et al. 2017). In contrast, the RCR E3 ligase provides a degree of allosteric activation to E2~Ub (Mabbitt et al. 2020; Pao et al. 2018). The RCR is unique in having two catalytic cysteines. The upstream cysteine accepts Ub from the E2 and subsequently relays Ub to the downstream cysteine. Finally, the downstream cysteine transfers Ub to threonine residues within protein substrates (Mabbitt et al. 2020; Pao et al. 2018).

A feature of many E2s and E3s is that they catalyse the formation of Ub polymers. Given Ub has 7 lysines, there are many possible linear and branched Ub chains; the physiological roles of these polymers has been reviewed extensively elsewhere (Haakonsen and Rape 2019; Stanley and Virdee 2016; Yau and Rape 2016). A recent report of ester-linked Ub polymers (Ub chains linked at threonine or serine) in vitro suggests that ester-linked Ub chains may also function in cell signalling (Kelsall et al. 2019). If this proves to be the case, serine and threonine would provide 10 potential branch points to Ub chains. Further complicating the Ub chain topology, Ub is cleaved from substrate proteins by one of many (~95 in humans) deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs). Deubiquitylating enzymes have been categorised into several families; however, mechanistically, they are all either cysteine proteases or zinc proteases (Nijman et al. 2005). Like the other members of the ubiquitylation cascade, DUBs display varying degrees of promiscuous activity (Table 1).

Activity-based probes for the ubiquitylation cascade

Chemical tools which directly detect an enzyme’s active site and subsequently covalently modify the enzyme are frequently referred to as activity-based probes (ABPs). Activity-based probes are a logical extension of dye or fluorophore-linked chemical probes that specifically modify thiols or amines. Compounds like Ellman’s reagent (5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) and Sanger’s reagent (1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene) are useful tools for quantifying thiols and amines, respectively, but they lack the specificity required to provide a qualitative readout of enzyme activity. Activity-based probes typically consist of three parts: warhead, recognition element and handle. The warhead (reactive group) is activated by the enzyme and subsequently covalently modifies the enzyme. The warhead is connected to a recognition element which provides specificity to the ABP. Finally, a handle such as a fluorophore or affinity tag facilitates detection of the ABP-enzyme complex (Heal et al. 2011; Liu et al. 1999; Speers and Cravatt 2004). The principal advantages of ABPs over other enzyme detection systems are as follows: firstly, that they report changes in activity even when expression levels are constant and secondly, that they detect enzyme mechanism irrespective of sequence (Liu et al. 1999). Coupling ABP labelling with mass spectrometry has facilitated the discovery of ubiquitinylating enzymes with modest sequence homology to known members of the pathway (Borodovsky et al. 2002; Pao et al. 2018).

Before discussing ABPs for the ubiquitylation cascade, it is important to distinguish between unimolecular (SN1) and bimolecular (SN2) nucleophilic substitutions. In the first step of SN1 reactions, loss of the leaving group results in a carbocation intermediate. The activation energy of the rate-determining step is inversely proportional to the stability of the carbocation or partial carbocation intermediate. In contrast, in SN2 reactions loss of the leaving group and bond formation are simultaneous. All ubiquitylating enzymes utilise a thiolate (S-) nucleophile that undergoes concerted (SN2) nucleophilic substitutions with the alkyl halide electrophiles employed in many ABPs. In SN2 reactions, the rate constant is determined by both the concentration of ABP and target enzyme. The effective concentration of the ABP-enzyme complex and hence the rate of reaction can be increased by incorporating a recognition element into the ABP. The use of recognition elements in ABPs is an extension of the organic chemistry principle of template-assembled synthesis where non-covalent interactions are used to promote covalent bond formation.

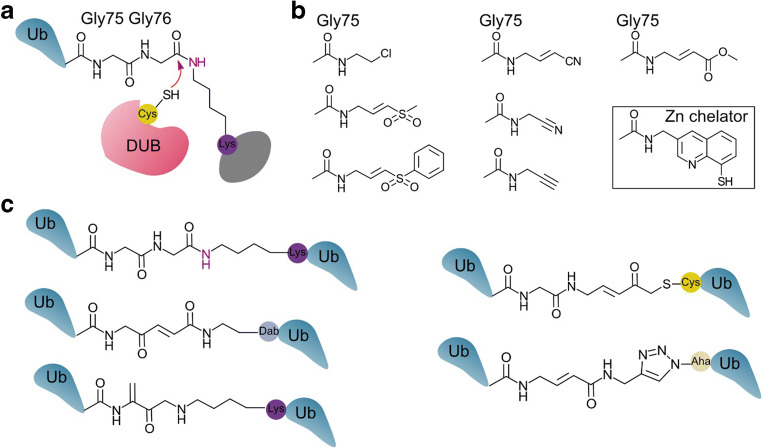

Like other cysteine proteases, DUBs that employ a cysteine protease mechanism are excellent targets for ABPs (Borodovsky et al. 2002; Faleiro et al. 1997; Greenbaum et al. 2000; Otto and Schirmeister 1997). In the earliest example of a DUB probe, radiolabelled Ub modified with a nitrile warhead served as an ABP for proteasome-associated DUBs (Lam et al. 1997). A later study uncovered a family of DUBs using ABPs with one of seven thiol reactive groups as the warhead (Borodovsky et al. 2002) (Fig. 2). Ideally, the warhead of an ABP will have limited off-target reactivity. This is particularly the case with cysteine reactive warheads, which at worst, are highly non-specific (Muller and Winter 2017). Of the available warheads, terminal alkynes appear to provide the best selectivity for cysteine protease DUBs over free thiols (Ekkebus et al. 2013). Deubiquitylating enzymes differ markedly in their specificity for isopeptide linkages within Ub dimers. Activity-based probes in which the warhead is placed between two Ub molecules (mimicking the isopeptide bond) allow the specificity of cysteine DUBs for Ub linkages to be probed (Li et al. 2014; McGouran et al. 2013) (Fig. 2). Metalloprotease DUBs have received little attention from the ABP community. Recently, an ABP with a zinc chelator (8-mercaptoquinoline) warhead was reported (Hameed et al. 2019). It is not yet clear if this warhead will be sufficiently specific to probe endogenously expressed metalloprotease DUBs.

Fig. 2.

Warheads employed in activity-based probes for deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs). a Cysteine DUBs cleave the isopeptide bond between Ub and a substrate protein. b The C-terminal glycine of Ub can be replaced by a thiol reactive group or a metal ion chelator (boxed) (Borodovsky et al. 2002; Ekkebus et al. 2013; Hameed et al. 2019; Lam et al. 1997). c Isopeptide-linked Ub dimers (depicted top left) are preferentially cleaved by many DUBs. Warheads can be placed between the Ub C-terminus and any of the 7 lysine positions in a second Ub. Construction of some DUB probes requires replacement of lysine with cysteine or the unnatural amino acids azidohomoalanine (Aha) or diaminobutyric acid (Dab) (Haj-Yahya et al. 2014; Li et al. 2014; McGouran et al. 2013; Mulder et al. 2014)

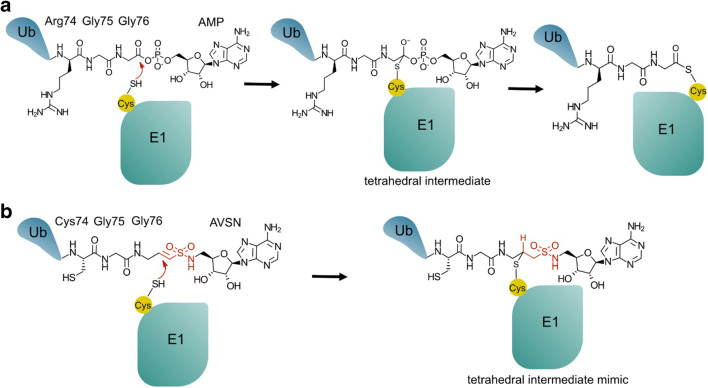

Activity-based probes for E1s, like cysteine-DUB probes, take advantage of the enzyme’s affinity for Ub and the reactivity of the active site cysteine. E1s adenylate the carboxyl terminus of Ub, transfer Ub to a conserved cysteine and subsequently transfer Ub to E2s. An E1-specific ABP was made by placing an electrophilic warhead (activated vinyl–sulfone) between Ub and an AMP mimic (Lu et al. 2010) (Fig. 3). Using this probe, E1–Ub complexes were isolated for structural studies (Hann et al. 2019; Lu et al. 2010; Olsen et al. 2010).

Fig. 3.

A warhead to capture the tetrahedral E1~Ub thioester intermediate. a E1 catalyses adenylation of Ub (not shown); subsequently. the catalytic cysteine attacks the adenylate resulting in a thioester bond between the Ub C-terminus and the E1. b An AVSN (5′-(vinylsulfonylaminodeoxy)adenosine) warhead attached to the modified C-terminus of Ub was used to trap a covalent E1-Ub-AVSN complex (Hann et al. 2019; Lu et al. 2010)

A second class of E1 ABP took advantage of the affinity of E2s for the E1. In this ABP, an E2 was used as the recognition element and the warhead was attached to the E2’s catalytic cysteine (Stanley et al. 2015). This ABP also reacted specifically with the active site cysteine of a bacterial HECT-like protein and an RBR E3 ligase in vitro (Stanley et al. 2015) (Fig. 4). Reactivity with HECT and RBR E3s was not surprising, given that structural studies suggest that a relatively small number of interactions are sufficient for E2~Ub binding and Ub transfer (Dove et al. 2017; Dove et al. 2016; Kamadurai et al. 2009; Lechtenberg et al. 2016; Yuan et al. 2017). The Virdee group further developed their E1 probe (Stanley et al. 2015), so that it had increased reactivity with cysteine E3s (Pao et al. 2016). In this ABP, an activated vinyl–sulphide warhead is placed between the C-terminus of Ub and the catalytic cysteine of the E2 (Pao et al. 2016) (Fig. 5). Addition of Ub to the ABP increased its affinity/reactivity with RBR E3s and allowed for profiling of an RBR E3’s activity in cell lysates (Pao et al. 2016). This ABP was subsequently used to profile cysteine-dependent E3s in cell lysates; the probe detected ~80 % of known human HECT and RCR E3s as well as E3s whose mechanism had not been fully described (Pao et al. 2016). One of these E3s was a 500-kDa protein with a RING domain at the C-terminus (known as MYCBP2), Pao and colleagues found that the 30-kDA C-terminal domain of MYCBP2 contains two catalytic cysteines. The upstream cysteine receives Ub from an E2 and subsequently relays Ub to the downstream cysteine. The downstream cysteine is positioned in a well-defined active site (similar to a canonical catalytic cysteine, histidine and glutamic acid catalytic triad). This second site is responsible for transfer of Ub to ester substrates (Pao et al. 2016). The MYCBP2 mechanism was dubbed RING-Cys-Relay (RCR). Subsequently, the X-ray crystal structure of the ABP-MYCBP2 complex was solved. This structure mimics the transthiolation intermediate where Ub is transferred from the catalytic cysteine of the E2 to the upstream catalytic cysteine of MYCBP2 (Mabbitt et al. 2020). It is likely that ABPs will continue to be improved and used to survey the catalytic diversity of cysteine-dependent E3s. Mechanistically, unique cysteine E3s, like MYCBP2, may be useful drug targets (Mabbitt et al. 2020).

Fig. 4.

ABP to capture E1-E2 transthiolation intermediate. a Ub is transferred from the active site cysteine of E1 to the active site cysteine of an E2 via transthiolation. b Modification of the E2 active site cysteine with an activated vinylsulfide warhead results in an ABP for E1 to E2 transthiolation (Stanley et al. 2015). c The ABP also selectively modified the active site cysteine of a small cohort of RBR and HECT E3s

Fig. 5.

ABP to capture E2-E3 transthiolation. a Ub is transferred from the active site cysteine of E2 to the active site cysteine of a HECT or RBR via transthiolation. a An ABP for HECT and RBR E3s. Both E2 and Ub (residues 1-73) serve as the recognition element and the activated vinyl sulphide warhead reacts with the catalytic cysteine of HECT and RBR E3s (Pao et al. 2016). The ABP also reacts specifically with E1 and RCR E3s (Mabbitt et al. 2020; Pao et al. 2018)

An elegant ABP which takes advantage of the promiscuous nature of the ubiquitylation cascade was presented by Mulder and colleagues (Mulder et al. 2016) (Fig. 6). They replaced the C-terminal glycine of Ub with dehydroalanine (Dha). Like Ub, Ub-Dha is activated by the E1 and is subsequently relayed to E2s and cysteine-dependent E3s. However, at each step, the activated methylene group of Dha can attack the enzymes catalytic cysteine to form a stable thioether bond (Mulder et al. 2016). In principle, this probe could facilitate the discovery of new E2s and cysteine-dependent E3s. However, at present, no new E2 or E3 has been discovered using Ub-Dha.

Fig. 6.

A cascading probe for the ubiquitin cysteine relay. Substitution of Gly76 with dehydroalanine (Dha) results in a cascading ABP. At each step in the cysteine relay, Ub-Dha can either be transferred or form a stable thioether adduct (Mulder et al. 2016)

Polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are produced as storage polymers by many bacterial species. A recent review provides a historical overview of the discovery of PHAs (Choi et al. 2020). Polyhydroxyalkanoate granules are closely associated with a group of regulatory, biosynthetic and DNA binding proteins resulting in an organelle-like structure(Jendrossek 2009). In nature, alkanoic acids incorporated into PHAs are derived from fatty acid biosynthesis and β oxidation. At least ten alternate pathways have been engineered to produce PHA precursors in the laboratory (Meng et al. 2014). Irrespective of origin, the alkanoic acid precursors are attached via a thioester bond to CoA. The hydroxyalkanoate–CoA thioester is then polymerised by PhaC (polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase). PhaC are stereospecific for (R)-n-hydroxy fatty acids, with the prototypical substrate being (R)-3-hydroxybutyric acid. Over 100 alternate substrates have been identified; however, it should be noted that these alternate substrates are often incorporated into random copolymers rather than pure homopolymers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases are highly promiscuous and can utilise at least 100 distinct substrates

| Enzyme class | Observed activities | Key references describing substrates |

|---|---|---|

| PhaC | Polymerisation of hydroxyalkanoates with between 2 and 6 carbons in the backbone of the polymer. The R-pendant (group not in the backbone of the polymer) is of variable length. R-pendants can contain epoxide groups, double bonds and variable terminal moieties. Terminal groups including alkyne, aromatic, aryloxy, cyano, halogen and nitrosyl groups. | (Choi et al. 2016; Curley et al. 1996; Hazer et al. 1996; Kim et al. 1998; Steinbüchel and Valentin 1995; Taguchi et al. 2008) |

| PhaZ | Cleave of polyhydroxyalkanoates | (de Eugenio et al. 2007; Jendrossek and Handrick 2002) |

PhaC have been separated into four classes based on their substrate preference and subunit composition. Class I PhaC preferentially utilise (R)-3-hydroxy fatty acids with between 3 and 5 carbons. Several X-ray crystal structures of the C-terminal catalytic domain of class I PhaC have been solved (Chek et al. 2017; Chek et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2017a; Wittenborn et al. 2016). The catalytic domain adopts an α/β-hydrolase fold with a cysteine, histidine and aspartic acid catalytic triad. A mobile subdomain protrudes from the canonical core of the α/β-hydrolase and appears to contribute to homodimerisation as well as providing a lid to the catalytic machinery (Chek et al. 2017; Chek et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2017a; Wittenborn et al. 2016). The N-terminal domain, missing from the crystallisation construct, is required for PhaC localisation to the PHA granule. Constructs lacking the N-terminal domain have negligible in vivo activity (Kim et al. 2017b).

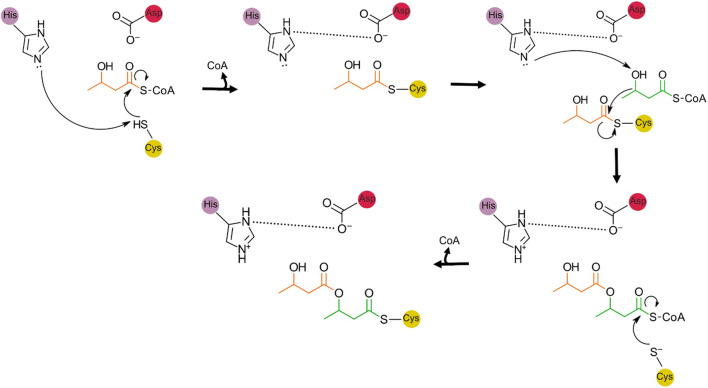

Two catalytic mechanisms have been proposed for PhaC. The first is a processive model requiring one active site and the second is a pingpong model requiring the sequential action of two active sites. Following publication of the X-ray crystal structure of Class I PhaC, the processive model has found favour. This is due to the distance between the active sites of monomers within the observed PhaC dimers being too large for the pingpong mechanism to take place (Chek et al. 2017; Chek et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2017a; Wittenborn et al. 2016). In the processive model, histidine deprotonates the catalytic cysteine, facilitating nucleophilic attack of the carbonyl carbon of the hydroxyalkanoate–CoA substrate. This results in a covalent hydroxyalkanoate thioester intermediate. A second hydroxyalkanoate–CoA then enters the active site and the terminal hydroxyl group is deprotonated by the aspartate–histidine diad (Kim et al. 2017a; Wittenborn et al. 2016) or directly by aspartate (Chek et al. 2020). The terminal alkoxide then attacks the carbonyl carbon resulting in growth of the PHA polymer (Chek et al. 2017; Chek et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2017a; Wittenborn et al. 2016) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Reaction scheme for PhaC catalysed 3-hydroxybutyrate polymerisation as proposed by Wittenborn et al. 2016. Histidine deprotonates the catalytic cysteine facilitating nucleophilic attack of the hydroxyalkanoate-CoA (3-hydroxybutyrate-CoA). A second hydroxyalkanoate-CoA binds and the hydroxyl group is deprotonated by histidine. The alkoxide then attacks the hydroxyalkanoate thioester resulting in a non-covalent intermediate. The hydroxyalkanoate chain is then transferred back to the catalytic cysteine. A modified reaction scheme, based on a CoA bound PhaC structure, has also been proposed. In this scheme, the catalytic histidine moves out of the active site following formation of the first covalent intermediate (Chek et al. 2020)

Class II PhaC preferentially polymerise (R)-3-hydroxy fatty acids with between 6 and14 carbons. Based on sequence similarity and structural predictions, Class II PhaCs are likely to adopt an α/β-hydrolase fold and utilise the same catalytic mechanism as their Class I counterparts (Amara and Rehm 2003). Class III PhaC form a heteromer with a second protein, PhaE, and this association is required for in vivo activity (Liebergesell et al. 1992). Similarly, Class IV PhaC form a heteromer with PhaR (McCool and Cannon 2001). The substrate specificity of Class III is similar to Class II, whilst the specificity of Class IV is variable (Liebergesell et al. 1993). Like other members of the α/β-hydrolase superfamily substrate, specificity is likely determined by the size and shape of the substrate binding site. However, in the case of PhaC, affinity for the product (PHA granules) driven by accessory proteins (PhaE or PhaR) or the N-terminal domain may contribute to specificity in vivo.

Polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerases (PhaZ)

Both intracellular and extracellular serine–hydrolases catalyse the depolymerisation of PHA. Intracellular PhaZ depolymerases mobilise hydroxyalkanoates when cells are subject to carbon limiting conditions. In contrast, extracellular PhaZ scavenge hydroxyalkanoates from the environment (Jendrossek and Handrick 2002). All PhaZ with known or predicted structures are α/β-hydrolases with a canonical serine, histidine and aspartate catalytic triad (Hisano et al. 2006; Jendrossek and Handrick 2002; Jendrossek et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2015). The key differences between depolymerases are the presence or absence of a secondary domain that binds PHA and the activity of the PhaZ with crystalline substrates as opposed to native amorphous substrates (Jendrossek and Handrick 2002).

Probes for CoA-dependent enzymes

Probes that label either the substrate or active site nucleophile in CoA-dependent reactions have been developed (Hwang et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2006) (Fig. 8). In the first example, chloroacetyl–CoA was used to identify the substrate of an N-acetyl transferase. Transfer of the chloroacetyl group resulted in a chloroacetylated protein that could subsequently be detected using a thiol reactive dye or affinity tag (Yu et al. 2006). This class of probe was improved by replacing the terminal chloride with an alkyne; the alkyne served as a handle for Cu(I)-catalysed azide-alkyne cycloaddition of an affinity tag (Yang et al. 2010). A second class of probe utilises a thiocarbamate sulfoxide warhead that carbamylates the nucleophile of CoA-dependent enzymes (Hwang et al. 2007). The probe designed by Hwang and colleagues was successfully utilised with purified N-acetyl transferases and N-acetyl transferases in cell lysates. However, the specificity of the probe in lysates is not clear.

Fig. 8.

Tools for probing coenzyme A (CoA)-dependent enzymes. a Chloroacetyl-CoA is transferred to substrates by N-acetyl transferases. The chloroacetlyated protein can then be detected using thiol reactive fluorophores or biotin(Yu et al. 2006). b Pentynoyl CoA is transferred to substrates by N-acetyl transferases. The modified protein can then be detected by Cu(I)-catalysed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) of biotin or a fluorophore (Yang et al. 2010). c A sulfocarbamate warhead between CoA and desthiobiotin was employed to label the catalytic cysteine of an N-acetyl transferase (Hwang et al. 2007)

Chemical tools for probing PhaC

Activity-based probes could be used to isolate covalent PhaC-substrate intermediates for structural studies or to identify novel PhaC-like enzymes. For structural studies, ABPs can trap mechanistically informative intermediates. The covalent PhaC–hydroxyalkanoate–CoA transition state is analogous to the covalent E1–E2–Ub transition state. Activity-based probes similar to those employed with the ubiquitylation machinery could be used to trap PhaC–hydroxyalkanoate–CoA complex (Lu et al. 2010; Stanley et al. 2015). This class of ABP could also be used to identify PhaC-like enzymes. The caveat here is that the CoA moiety would provide the majority of the recognition element and the probe would be expected to react with non-target CoA-dependent enzymes.

An outstanding question in PhaC mechanism is what the steric constraints are on the side group (R-pendant) of the hydroxyalkanoate and how these constraints differ between PhaC classes. A substrate mimic that alkylates the active site cysteine of PhaC (i.e., a PhaC inhibitor) could be used to isolate covalent PhaC hydroxyalkanoate complexes for structural studies. Similar probes have been instrumental in elucidating the mechanisms of cysteine proteases (Otto and Schirmeister 1997).

Activity-based probes for PhaZ

Probes with a flurophosphonate warhead have been successfully employed with recombinant PhaZ (Huang et al. 2012). In order to improve the specificity of this class of broad-spectrum serine–hydrolase probe, a hydroxyalkanoate recognition element could be incorporated between the warhead and handle; many analogous probes with short-peptide recognition elements have been developed (Faucher et al. 2020; Liu et al. 1999).

Engineering cysteine relays

Given the promiscuity of cysteine relays, it would appear a simple task to engineer novel polymers. In many instances, the difficulty is not finding a promiscuous activity, rather it is that the yield of product is sufficient for biochemical assays but insufficient for large-scale production. For example, only trace amounts of Ub linked by an ester bond to serine could be produced using the RCR E3 ligase, whereas large amounts of threonine linked-Ub can be produced under the same reaction conditions (De Cesare et al. 2021). Similarly, only small amounts of ester-linked Ub dimers can be produced in vitro using the RBR E3 ligase HOIL-1 (Kelsall et al. 2019).There is potential to improve both E3s by computational design or laboratory-directed evolution; however, this would be a major undertaking given the lack of a high-throughput assay and the complexity of the RBR and RCR catalytic mechanisms. It is more likely that better catalysts will be obtained by screening the thousands of naturally occurring E2s and E3s using conventional enzyme assays or ABPs.

The recent PhaC structures should allow for computational design of PhaC variants with altered substrate specificity. A hydroxyalkanoate bound structure and a structure of a Class II PhaC would further facilitate the design process. In the absence of a strong selective pressure or a high-throughput assay, laboratory-directed evolution of PhaC would be difficult but not impossible (Kichise et al. 2002). It is possible that PhaC-like proteins that lack sequence homology with the established classes exist in nature and that these could be identified using ABPs. Similar studies have uncovered new serine hydrolases (Lentz et al. 2018; Ortega et al. 2016). Ideally, multiple microbial species would be profiled simultaneously. The challenge here is that identification of labelled proteins by mass spectrometry relies on database searching and a robust method to search proteomes of multiple related species would need to be implemented (Cheng et al. 2018; Schiebenhoefer et al. 2019). Whilst it has been demonstrated that microbial communities can be probe labelled, separated and subsequently identified by 16S rRNA sequencing (Whidbey et al. 2019), to my knowledge, mass spectrometry-based ABP-profiling has not been achieved with microbial communities.

Conclusions

When engineering a cysteine relay to use a novel substrate, we choose the starting point; either we improve the latent promiscuous activity of well a characterised ligase or screen for a new ligase. Activity-based probe profiling widens the screening net to include mechanistically similar but not necessarily evolutionarily related enzymes. It is likely that ABP profiling will continue to uncover ligases with unusual substrate specificity and that these enzymes will be the equal or better of those engineered in the laboratory.

Funding

I am grateful for the financial support provided by Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment New Zealand via Scion’s Strategic Science Investment Fund contract C04X1703.

Data Availability

All underlying data are available from the author upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahel J, Lehner A, Vogel A, Schleiffer A, Meinhart A, Haselbach D, Clausen T (2020) Moyamoya disease factor RNF213 is a giant E3 ligase with a dynein-like core and a distinct ubiquitin-transfer mechanism. Elife 9. 10.7554/eLife.56185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Amara AA, Rehm BH. Replacement of the catalytic nucleophile cysteine-296 by serine in class II polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated synthesis of a new polyester: identification of catalytic residues. Biochem J. 2003;374:413–421. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky A, Ovaa H, Kolli N, Gan-Erdene T, Wilkinson KD, Ploegh HL, Kessler BM. Chemistry-based functional proteomics reveals novel members of the deubiquitinating enzyme family. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1149–1159. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00248-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchak ON, Jaquinod M, Cottin C, Mugherli L, Iwai K, Chatelain F, Balakirev MY. Chemoenzymatic ubiquitination of artificial substrates. Chembiochem. 2006;7:1667–1669. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappadocia L, Lima CD. Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation: structures, chemistry, and mechanism. Chem Rev. 2018;118:889–918. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chek MF, Kim SY, Mori T, Arsad H, Samian MR, Sudesh K, Hakoshima T. Structure of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase PhaC from Chromobacterium sp. USM2, producing biodegradable plastics. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5312. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chek MF, Kim SY, Mori T, Tan HT, Sudesh K, Hakoshima T. Asymmetric open-closed dimer mechanism of polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase. PhaC iSci. 2020;23:101084. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K, Ning Z, Zhang X, Mayne J, Figeys D. Separation and characterization of human microbiomes by metaproteomics. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2018;108:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Park SJ, Kim WJ, Yang JE, Lee H, Shin J, Lee SY. One-step fermentative production of poly(lactate-co-glycolate) from carbohydrates in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:435–440. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Rhie MN, Kim HT, Joo JC, Cho IJ, Son J, Jo SY, Sohn YJ, Baritugo KA, Pyo J, Lee Y, Lee SY, Park SJ. Metabolic engineering for the synthesis of polyesters: a 100-year journey from polyhydroxyalkanoates to non-natural microbial polyesters. Metab Eng. 2020;58:47–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley JM, Hazer B, Lenz RW, Fuller RC. Production of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) containing aromatic substituents by Pseudomonas oleovorans. Macromolecules. 1996;29:1762–1766. doi: 10.1021/ma951185a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dang LC, Melandri FD, Stein RL. Kinetic and mechanistic studies on the hydrolysis of ubiquitin C-terminal 7-amido-4-methylcoumarin by deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1868–1879. doi: 10.1021/bi9723360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cesare V, Carbajo Lopez D, Mabbitt PD, Fletcher AJ, Soetens M, Antico O, Wood NT, Virdee S (2021) Deubiquitinating enzyme amino acid profiling reveals a class of ubiquitin esterases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A:118. 10.1073/pnas.2006947118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- de Eugenio LI, Garcia P, Luengo JM, Sanz JM, Roman JS, Garcia JL, Prieto MA. Biochemical evidence that phaZ gene encodes a specific intracellular medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerase in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: characterization of a paradigmatic enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4951–4962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove KK, Olszewski JL, Martino L, Duda DM, Wu XS, Miller DJ, Reiter KH, Rittinger K, Schulman BA, Klevit RE. Structural studies of HHARI/UbcH7 approximately Ub reveal unique E2 approximately Ub conformational restriction by RBR RING1. Structure. 2017;25:890–900.e895. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove KK, Stieglitz B, Duncan ED, Rittinger K, Klevit RE. Molecular insights into RBR E3 ligase ubiquitin transfer mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1221–1235. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Mms2-Ubc13 covalently bound to ubiquitin reveals the structural basis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chain formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:915–920. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekkebus R, van Kasteren SI, Kulathu Y, Scholten A, Berlin I, Geurink PP, de Jong A, Goerdayal S, Neefjes J, Heck AJR, Komander D, Ovaa H. On terminal alkynes that can react with active-site cysteine nucleophiles in proteases. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2867–2870. doi: 10.1021/ja309802n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Oualid F, Merkx R, Ekkebus R, Hameed DS, Smit JJ, de Jong A, Hilkmann H, Sixma TK, Ovaa H. Chemical synthesis of ubiquitin, ubiquitin-based probes, and diubiquitin. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 2010;49:10149–10153. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faleiro L, Kobayashi R, Fearnhead H, Lazebnik Y. Multiple species of CPP32 and Mch2 are the major active caspases present in apoptotic cells. EMBO J. 1997;16:2271–2281. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucher F, Bennett JM, Bogyo M, Lovell S. Strategies for tuning the selectivity of chemical probes that target serine hydrolases. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27:937–952. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum D, Medzihradszky KF, Burlingame A, Bogyo M. Epoxide electrophiles as activity-dependent cysteine protease profiling and discovery tools. Chem Biol. 2000;7:569–581. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haakonsen DL, Rape M. Branching out: improved signaling by heterotypic ubiquitin chains. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:704–716. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Yahya N, Hemantha HP, Meledin R, Bondalapati S, Seenaiah M, Brik A. Dehydroalanine-based diubiquitin activity probes. Org Lett. 2014;16:540–543. doi: 10.1021/ol403416w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed DS, Sapmaz A, Burggraaff L, Amore A, Slingerland CJ, van Westen GJP, Ovaa H. Development of ubiquitin-based probe for metalloprotease deubiquitinases. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 2019;58:14477–14482. doi: 10.1002/anie.201906790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann ZS, Ji C, Olsen SK, Lu X, Lux MC, Tan DS, Lima CD. Structural basis for adenylation and thioester bond formation in the ubiquitin E1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:15475–15484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905488116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazer B, Lenz RW, Clinton Fuller R. Bacterial production of poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates containing arylalkyl substituent groups. Polymer. 1996;37:5951–5957. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(96)00570-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heal WP, Dang TH, Tate EW. Activity-based probes: discovering new biology and new drug targets. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:246–257. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00004c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano T, Kasuya K, Tezuka Y, Ishii N, Kobayashi T, Shiraki M, Oroudjev E, Hansma H, Iwata T, Doi Y, Saito T, Miki K. The crystal structure of polyhydroxybutyrate depolymerase from Penicillium funiculosum provides insights into the recognition and degradation of biopolyesters. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:993–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann R, Akimoto G, Wucherpfennig TG, Zeymer C, Bode JW. Lysine acylation using conjugating enzymes for site-specific modification and ubiquitination of recombinant proteins. Nat Chem. 2020;12:1008–1015. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0528-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YL, Chung TW, Chang CM, Chen CH, Liao CC, Tsay YG, Shaw GC, Liaw SH, Sun CM, Lin CH. Qualitative analysis of the fluorophosphonate-based chemical probes using the serine hydrolases from mouse liver and poly-3-hydroxybutyrate depolymerase (PhaZ) from Bacillus thuringiensis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:2387–2396. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y, Thompson PR, Wang L, Jiang L, Kelleher NL, Cole PA. A selective chemical probe for coenzyme A-requiring enzymes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:7621–7624. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek D. Polyhydroxyalkanoate granules are complex subcellular organelles (carbonosomes) J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3195–3202. doi: 10.1128/JB.01723-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek D, Handrick R. Microbial degradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:403–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek D, Hermawan S, Subedi B, Papageorgiou AC. Biochemical analysis and structure determination of Paucimonas lemoignei poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) depolymerase PhaZ7 muteins reveal the PHB binding site and details of substrate-enzyme interactions. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:649–664. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamadurai HB, Souphron J, Scott DC, Duda DM, Miller DJ, Stringer D, Piper RC, Schulman BA. Insights into ubiquitin transfer cascades from a structure of a UbcH5B approximately ubiquitin-HECT(NEDD4L) complex. Mol Cell. 2009;36:1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsall IR, Zhang J, Knebel A, Arthur JSC, Cohen P. The E3 ligase HOIL-1 catalyses ester bond formation between ubiquitin and components of the Myddosome in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:13293–13298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905873116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kichise T, Taguchi S, Doi Y (2002) Enhanced accumulation and changed monomer composition in polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) copolyester by in vitro evolution of Aeromonas caviae PHA Synthase. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:2411. 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2411-2419.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim DY, Kim Y, Rhee YH. Bacterial poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) bearing carbon-carbon triple bonds. Macromolecules. 1998;31:4760–4763. doi: 10.1021/ma980208t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim YJ, Choi SY, Lee SY, Kim KJ (2017a) Crystal structure of Ralstonia eutropha polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase C-terminal domain and reaction mechanisms. Biotechnol J 12. 10.1002/biot.201600648 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim YJ, Choi SY, Kim J, Jin KS, Lee SY, Kim KJ (2017b) Structure and function of the N-terminal domain of Ralstonia eutropha polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase, and the proposed structure and mechanisms of the whole enzyme. Biotechnol J 12. 10.1002/biot.201600649 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lam YA, Xu W, DeMartino GN, Cohen RE. Editing of ubiquitin conjugates by an isopeptidase in the 26S proteasome. Nature. 1997;385:737–740. doi: 10.1038/385737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau YK, Baytshtok V, Howard TA, Fiala BM, Johnson JM, Carter LP, Baker D, Lima CD, Bahl CD. Discovery and engineering of enhanced SUMO protease enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:13224–13233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtenberg BC, Rajput A, Sanishvili R, Dobaczewska MK, Ware CF, Mace PD, Riedl SJ. Structure of a HOIP/E2~ubiquitin complex reveals RBR E3 ligase mechanism and regulation. Nature. 2016;529:546–550. doi: 10.1038/nature16511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz CS, Sheldon JR, Crawford LA, Cooper R, Garland M, Amieva MR, Weerapana E, Skaar EP, Bogyo M. Identification of a S. aureus virulence factor by activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) Nat Chem Biol. 2018;14:609–617. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0060-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Liang Q, Gong P, Tencer AH, Zhuang Z. Activity-based diubiquitin probes for elucidating the linkage specificity of deubiquitinating enzymes. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50:216–218. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47382a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebergesell M, Mayer F, Steinbüchel A. Anaylsis of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid-biosynthesis genes of anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria reveals synthesis of a polyester exhibiting an unusal composition. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;40:292–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00170383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liebergesell M, Schmidt B, Steinbuchel A. Isolation and identification of granule-associated proteins relevant for poly(3-hydroxyalkanoic acid) biosynthesis in Chromatium vinosum D FEMS. Microbiol Lett. 1992;78:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90031-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Hou J, Cai S, Zhao D, Cai L, Han J, Zhou J, Xiang H. A patatin-like protein associated with the polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granules of Haloferax mediterranei acts as an efficient depolymerase in the degradation of native PHA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:3029–3038. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04269-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Activity-based protein profiling: the serine hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14694–14699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwocha J, Krist DT, van der Heden van Noort GJ, Hansen FM, Truong VH, Karayel O, Purser N, Houston D, Burton N, Bostock MJ, Sattler M, Mann M, Harrison JS, Kleiger G, Ovaa H, Schulman BA. Linkage-specific ubiquitin chain formation depends on a lysine hydrocarbon ruler. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;17:272–279. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00696-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Olsen SK, Capili AD, Cisar JS, Lima CD, Tan DS. Designed semisynthetic protein inhibitors of Ub/Ubl E1 activating enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1748–1749. doi: 10.1021/ja9088549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabbitt PD, Loreto A, Dery MA, Fletcher AJ, Stanley M, Pao KC, Wood NT, Coleman MP, Virdee S. Structural basis for RING-Cys-Relay E3 ligase activity and its role in axon integrity. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16:1227–1236. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0598-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakhov MP, Mattern MR, Malakhova OA, Drinker M, Weeks SD, Butt TR. SUMO fusions and SUMO-specific protease for efficient expression and purification of proteins. J Struct Funct Genom. 2004;5:75–86. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029237.70316.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin I, Lucas JI, Gradilla AC, Ferrus A. Parkin and relatives: the RBR family of ubiquitin ligases. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:253–263. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00226.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCool GJ, Cannon MC. PhaC and PhaR are required for polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthase activity in Bacillus megaterium. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4235–4243. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4235-4243.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGouran JF, Gaertner SR, Altun M, Kramer HB, Kessler BM. Deubiquitinating enzyme specificity for ubiquitin chain topology profiled by di-ubiquitin activity probes. Chem Biol. 2013;20:1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng DC, Shen R, Yao H, Chen JC, Wu Q, Chen GQ. Engineering the diversity of polyesters. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;29:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder MP, Witting K, Berlin I, Pruneda JN, Wu KP, Chang JG, Merkx R, Bialas J, Groettrup M, Vertegaal AC, Schulman BA, Komander D, Neefjes J, El Oualid F, Ovaa H. A cascading activity-based probe sequentially targets E1-E2-E3 ubiquitin enzymes. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:523–530. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder MPC, El Oualid F, ter Beek J, Ovaa H. A native chemical ligation handle that enables the synthesis of advanced activity-based probes: diubiquitin as a case study. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:946–949. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller T, Winter D. Systematic evaluation of protein reduction and alkylation reveals massive unspecific side effects by iodine-containing reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017;16:1173–1187. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.064048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, Bernards R. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SK, Capili AD, Lu X, Tan DS, Lima CD. Active site remodelling accompanies thioester bond formation in the SUMO E1. Nature. 2010;463:906–912. doi: 10.1038/nature08765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SK, Lima CD. Structure of a ubiquitin E1-E2 complex: insights to E1-E2 thioester transfer. Mol Cell. 2013;49:884–896. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega C, Anderson LN, Frando A, Sadler NC, Brown RW, Smith RD, Wright AT, Grundner C. Systematic survey of serine hydrolase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis defines changes associated with persistence. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto H-H, Schirmeister T. Cysteine proteases and their inhibitors. Chem Rev. 1997;97:133–172. doi: 10.1021/cr950025u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao KC, Stanley M, Han C, Lai YC, Murphy P, Balk K, Wood NT, Corti O, Corvol JC, Muqit MM, Virdee S. Probes of ubiquitin E3 ligases enable systematic dissection of parkin activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:324–331. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao KC, Wood NT, Knebel A, Rafie K, Stanley M, Mabbitt PD, Sundaramoorthy R, Hofmann K, van Aalten DMF, Virdee S. Activity-based E3 ligase profiling uncovers an E3 ligase with esterification activity. Nature. 2018;556:381–385. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plechanovova A, Jaffray EG, Tatham MH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature. 2012;489:115–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose IA, Warms JV. An enzyme with ubiquitin carboxy-terminal esterase activity from reticulocytes. Biochemistry. 1983;22:4234–4237. doi: 10.1021/bi00287a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Deshaies RJ. Multimodal activation of the ubiquitin ligase SCF by Nedd8 conjugation. Mol Cell. 2008;32:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner M, Nuber U, Huibregtse JM. Protein ubiquitination involving an E1-E2-E3 enzyme ubiquitin thioester cascade. Nature. 1995;373:81–83. doi: 10.1038/373081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebenhoefer H, Van Den Bossche T, Fuchs S, Renard BY, Muth T, Martens L. Challenges and promise at the interface of metaproteomics and genomics: an overview of recent progress in metaproteogenomic data analysis. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2019;16:375–390. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2019.1609944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Chemical strategies for activity-based proteomics. Chembiochem. 2004;5:41–47. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Han C, Knebel A, Murphy P, Shpiro N, Virdee S. Orthogonal thiol functionalization at a single atomic center for profiling transthiolation activity of E1 activating enzymes ACS. Chem Biol. 2015;10:1542–1554. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Virdee S. Chemical ubiquitination for decrypting a cellular code. Biochem J. 2016;473:1297–1314. doi: 10.1042/BJ20151195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbüchel A, Valentin HE. Diversity of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;128:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00125-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi S, Yamada M, Ki M, Tajima K, Satoh Y, Munekata M, Ohno K, Kohda K, Shimamura T, Kambe H, Obata S. A microbial factory for lactate-based polyesters using a lactate-polymerizing enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:17323–17327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805653105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Herr RA, Rabelink M, Hoeben RC, Wiertz EJ, Hansen TH. Ube2j2 ubiquitinates hydroxylated amino acids on ER-associated degradation substrates. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:655–668. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel DM, Lissounov A, Brzovic PS, Klevit RE. UBCH7 reactivity profile reveals parkin and HHARI to be RING/HECT hybrids. Nature. 2011;474:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature09966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whidbey C, Sadler NC, Nair RN, Volk RF, DeLeon AJ, Bramer LM, Fansler SJ, Hansen JR, Shukla AK, Jansson JK, Thrall BD, Wright AT. A probe-enabled approach for the selective isolation and characterization of functionally active subpopulations in the gut microbiome. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:42–47. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b09668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenborn EC, Jost M, Wei Y, Stubbe J, Drennan CL. Structure of the catalytic domain of the class I polyhydroxybutyrate synthase from Cupriavidus necator. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:25264–25277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CC, Zhang D, Hann DR, Xie ZP, Staehelin C. Biochemical properties and in planta effects of NopM, a rhizobial E3 ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:15304–15315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YY, Ascano JM, Hang HC. Bioorthogonal chemical reporters for monitoring protein acetylation. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3640–3641. doi: 10.1021/ja908871t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau R, Rape M. The increasing complexity of the ubiquitin code. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:579–586. doi: 10.1038/ncb3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, de Carvalho LP, Sun G, Blanchard JS. Activity-based substrate profiling for Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferases: the use of chloroacetyl-coenzyme A to identify protein substrates. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15356–15357. doi: 10.1021/ja066298w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Lv Z, Atkison JH, Olsen SK. Structural insights into the mechanism and E2 specificity of the RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase HHARI. Nat Commun. 2017;8:211. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All underlying data are available from the author upon request.

Not applicable.