Abstract

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is the cellular receptor for SARS-CoV-2, so ACE2-expressing cells can act as target cells and are susceptible to infection. ACE2 receptors are highly expressed in the oral cavity, so this may be a potential high-risk route for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Furthermore, the virus can be detected in saliva, even before COVID-19 symptoms appear, with the consequent high risk of virus transmission in asymptomatic/presymptomatic patients. Reducing oral viral load could lead to a lower risk of transmission via salivary droplets or aerosols and therefore contribute to the control of the pandemic. Our aim was to evaluate the available evidence testing the in-vitro and in-vivo effects of oral antiseptics to inactivate or eradicate coronaviruses. The criteria used were those described in the PRISMA declaration for performing systematic reviews. An electronic search was conducted in Medline (via PubMed) and in Web of Sciences, using the MeSH terms: ‘mouthwash’ OR ‘oral rinse’ OR ‘mouth rinse’ OR ‘povidone iodine’ OR ‘hydrogen peroxide’ OR ‘cetylpyridinium chloride’ AND ‘COVID-19’ OR ‘SARS-CoV-2’ OR ‘coronavirus’ OR ‘SARS’ OR ‘MERS’. The initial search strategy identified 619 articles on two electronic databases. Seventeen articles were included assessing the virucidal efficacy of oral antiseptics against coronaviruses. In conclusion, there is sufficient in-vitro evidence to support the use of antiseptics to potentially reduce the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses. However, in-vivo evidence for most oral antiseptics is limited. Randomized clinical trials with a control group are needed to demonstrate its clinical efficacy.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Coronaviruses, Oral rinse, Oral antiseptics

Introduction

On January 8th, 2020, a novel coronavirus was officially announced as the causative pathogen of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The COVID-19 pandemic started in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. On January 30th, 2020, the World Health Organization announced that this outbreak had constituted a public health emergency of international concern [1].

The term COVID-19 includes respiratory conditions that vary from the common cold to severe pneumonia with respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, and multi-organ failure [2]. This disease is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is a positive single-stranded RNA virus, and belongs to a large family of enveloped viruses from the betacoronavirus genus. It has spike-shaped proteins (peplomers) on its spherical surface that give it a crown-like appearance. The capsid (outer layer of protein) provides specificity to the virus and the inner core provides infectivity and contains enveloped proteins associated with the life cycle of the virus (assembly, envelope formation, and pathogenesis). The lipid bilayer with glycoproteins helps the virus identify the host cell and fuses with its membrane. Peplomers aid in the binding of virus to host [3].

With the advance of the pandemic, there has been a plethora of studies on the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 and its mechanism of spread, but current knowledge of antiviral activity in available drugs is largely based on the characteristics of similar coronaviruses. So far novel coronavirus (CoV) outbreaks have been associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome SARS-CoV-2 (2019), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus MERS-CoV (2012), and severe acute respiratory syndrome SARS-CoV-1 (2003) events. There are genomic similarities between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV (82%), which caused a major outbreak of SARS with 8098 cases, 774 deaths, and a final mortality rate of 9% in 2002–2003 [4,5]. MERS-CoV was first isolated from a man aged 60 years in Saudi Arabia in June 2012. Three years later, it has been responsible for the infection of more than 1300 individuals in 26 countries, and for more than 480 related deaths [6].

Because no highly effective treatment for COVID-19 is currently available, most public health measures are based on preventing the spread of the virus, which is transmitted by the respiratory route (respiratory droplets and probably aerosols) and by direct contact with contaminated surfaces and subsequent contact with nasal, oral, or ocular mucosa [7]. In particular, a very rapid spread of COVID-19 has been detected by relatively easy transmission through coughing, sneezing, and inhaling droplets. There may be a risk of faecal–oral transmission, as SARS-CoV-2 has been identified in the faeces of patients and in sewage. However, the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to the community through the faecal–oral route has not yet been established [3]. Additionally, it has not yet been confirmed whether SARS-CoV-2 can be spread by vertical transmission (from mothers to newborns) [8,9].

Although patients with symptomatic COVID-19 are the main source of transmission, observations suggest that asymptomatic patients and patients in their incubation period (presymptomatic) also have the ability to transmit SARS-CoV-2 [[10], [11], [12]]. The incubation period can range from 0 to 24 days, therefore transmission can occur before any symptoms are apparent [5,11,13]. This epidemiological characteristic of COVID-19, together with the long period of days when symptoms are mild enough not to limit the mobility of patients, has made their management extremely challenging, as it is difficult to identify and quarantine these patients in time, which may lead to an increase in community transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, it remains to be tested whether patients in the recovery phase are a potential source of virus transmission [11].

SARS-CoV-2 virus and the oral cavity

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is the cellular receptor for SARS-CoV-2 (which in turn is also the receptor for SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63), which interacts with the spike protein to facilitate its entry [9,14]. ACE2 plays an important role in the cellular entry of the virus. Therefore, ACE2-expressing cells can act as susceptible target cells to SARS-CoV-2 adhesion and infection.

The virus replicates mainly in the lungs, in addition to the heart, intestines, blood vessels, and muscles [3]. High expression of ACE2 was identified in type II alveolar cells (AT2) of the lung, stratified epithelial cells of the oesophagus, enterocytes of the ileum and colon, cholangiocytes, myocardial cells, cells of the proximal tubule of the kidney, and urothelial cells of the bladder. On the other hand, ACE2 receptors are highly expressed in the oral cavity and are abundant in epithelial cells. These findings indicate that the mucosa of the oral cavity may be a potential high-risk route for SARS-CoV-2 infection. The mean expression of ACE2 was higher in the tongue than in other oral tissues (95.86% of oral ACE2 receptors are found in this organ). Additionally, ACE2-positive cells can be found in other oral tissues, including epithelial cells (1.19% ACE2-positive cells), T cells (<0.5%), B cells (<0.5%), and fibroblasts (<0.5%); 93.38% of ACE2-positive cells are epithelial cells. The expression of ACE2 has been analysed in human organs and has been found to be higher in the minor salivary glands than in the lungs. Interestingly, it was found that ACE2 is also expressed on lymphocytes within the oral mucosa, and similar results were found in various organs of the digestive system and in the lungs [14].

In a recent study, it was determined that, in addition to ACE2, there are other molecules that promote the entry of the virus into the host cell. Transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) is a cell-surface protein strongly expressed in stratified squamous epithelium in the keratinized surface layer and detected in saliva and tongue-coating samples. It helps release viral RNA into host cell cytoplasm [15]. Furthermore, furin is an enzyme mainly expressed in the lower layer of stratified squamous epithelium and detected in saliva, but not in the lining of the tongue. It helps to activate the spike protein (S) binding process with the ACE2 receptor. Although the oral cavity may be the route of entry for SARS-CoV-2, other factors, including protease inhibitors in saliva that inhibit viral entry, must be considered. In addition, the sulcular epithelium co-expresses ACE2 and TMPRSS2, suggesting that the periodontal pocket may be a focal point of infection [15].

It was also published in 2004 that SARS-CoV RNA could be detected in saliva before lung lesions appeared [16]. In addition, the prevalence of patients admitted to the hospital with a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 and with SARS-CoV-2 in saliva can reach 91.7% [17]. Therefore, this suggests that COVID-19 infection caused by asymptomatic patients could stem from the presence of the virus in saliva [18].

It has been suggested that there are at least three different pathways for SARS-CoV-2 to be present in saliva: first, from the upper and lower respiratory tracts that enter the oral cavity along with the frequently exchanged droplets of fluid; second, through the crevicular fluid; and finally, by direct virus infection in the major and minor salivary glands, with the subsequent release of particles into the saliva through the mechanism of saliva secretion from salivary ducts [19].

Healthcare personnel who handle patients with aerodigestive tract diseases are the workers most at risk of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, there is a particular need for protective measures in these professional groups [20,21]. The risk of contamination is very high in upper respiratory examinations. In Chinese patients, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in 63% of nasopharyngeal swabs, 46% of fibreoptic bronchoscopic biopsies, and 93% of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples [20,22,23]. Higher viral loads were detected after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, with a higher viral load in the nose compared to that in the throat [20].

It has been proposed that the role of the oral cavity as a portal for the entry of the virus into the body and as a viral reservoir can be controlled through the use of antiseptics at two levels. First, by reducing pathogenicity (the decrease in SARS-CoV-2 viral load has been associated with a reduction in the severity of COVID-19) [24,25] and second, by reducing transmission of the virus (by lowering the viral load, the amount of virus shed by the patient may be temporarily reduced, thus reducing the risk of transmission). But the likely impact of daily use of these antiseptics for limited periods of time on viral transmission has not been explored. This proposed beneficial impact could be even more relevant in light of the anticipated evolution of the pandemic [26].

Thus, prevention procedures involving oral mouthwashes have been proposed as a low-cost and easy-to-implement strategy to reduce risk of infection for professionals. In addition, it could help to reduce the risk of transmission by salivary droplets and aerosols. With this in mind, in the current study we have reviewed the available evidence of the virucidal action of different oral antiseptics against SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses, both in vitro and in vivo, in order to evaluate its potential as a valid preventive strategy.

Methods

Search strategy

An electronic search in Medline (via PubMed) and in Web of Sciences, without temporal restriction updated to January 2021, using a combination of the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and Boolean operators, was performed: ‘mouthwash’ OR ‘oral rinse’ OR ‘mouth rinse’ OR ‘povidone iodine’ OR ‘hydrogen peroxide’ OR ‘cetylpyridinium chloride’ AND ‘COVID-19’ OR ‘SARS-CoV-2’ OR ‘coronavirus’ OR ‘SARS’ OR ‘MERS’.

The present review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines. The objective of this systematic review was to answer the following ‘PICO’ (P, patient/problem/population; I, intervention; C, comparison; O, outcome) question (Table I ): Do oral antiseptics have virucidal efficacy against coronaviruses?

Table I.

PICOa question breakdown

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Problem | Oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 virus |

| Intervention | Oral antiseptics |

| Comparison | Comparison between the use/non-use of oralantiseptics to reduce the viral load of the SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses |

| Outcome | COVID-19 prevention |

| PICO question | Do oral antiseptics have virucidal efficacy against coronaviruses? |

P, patient/problem/population; I, intervention; C, comparison; O, outcome.

Before the beginning of the study, a consensus was reached among all the authors, and a series of inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined.

Inclusion criteria

Only studies assessing the virucidal effect of mouth rinse solutions to inactivate or eradicate SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses were included. The studies to be selected had to fulfil the following criteria: (a) studies in humans and in animals; (b) articles published in English or Spanish; (c) case reports and series; and (d) experimental laboratory studies.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following exclusion criteria were disregarded: (a) studies where the main topic was not the description of the effect of oral antiseptics on SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses; (b) systematic reviews; (c) reviews; (d) duplicate articles; (e) books or book chapters; (f) author comments; and (g) letters to the editor.

Bias risk assessment

Bias risk assessment was assessed independently by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers or the intervention of a third reviewer.

Results

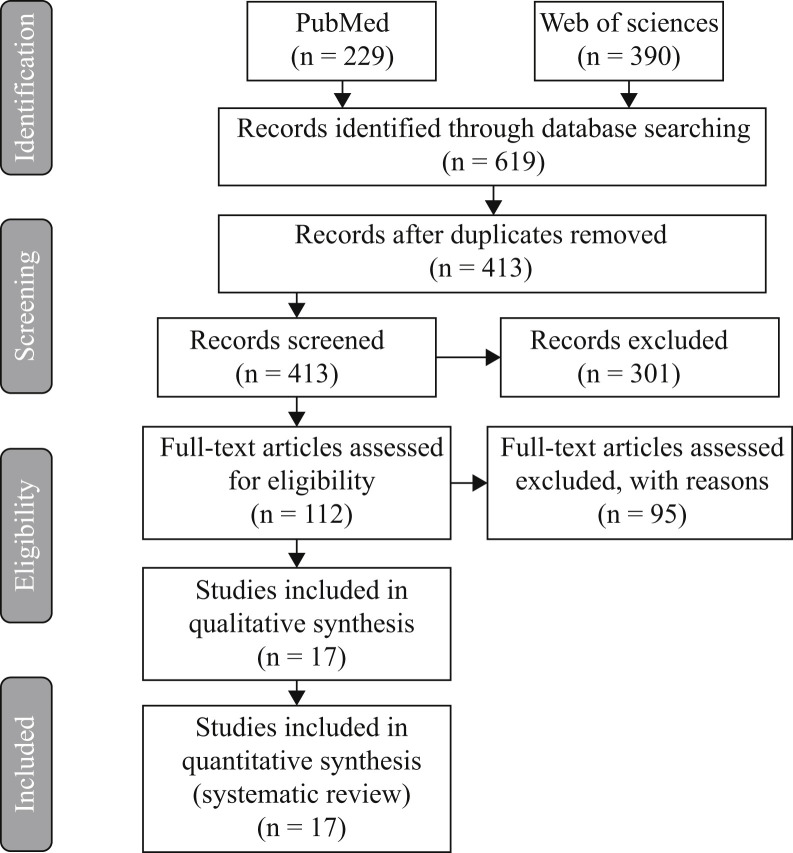

The initial search strategy on Medline via PubMed yielded 229 articles and 390 via Web of Sciences, of which 206 were excluded because they were duplicates. Two authors in consensus read the titles and summaries of the 413 remaining articles, and 301 of them were excluded because they were not directly concerned with the objective of the study. After the complete text of the 112 remaining articles had been read, 95 were excluded as they were not complying with the inclusion criteria established. Finally, 17 articles were included in the present review (Figure 1 ), describing the effect of oral antiseptics on SARS-CoV-2 and available studies on the use of antiseptics against other coronaviruses.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the search process and results.

One in-vivo study [27], four in-vitro studies [6,[28], [29], [30]], and one in-vivo and in-vitro study [31] were found to assess virucidal efficacy against other coronaviruses (Table II ). Regarding SARS-CoV-2, four studies were carried out in vivo [[32], [33], [34], [35]], and six in vitro, including one study performed with human cell lines [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]] (Table III ).

Table II.

Oral antiseptics against other coronaviruses: in-vivo and in-vitro studies

| Study | Study type | Test product | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eggers et al. [6] | In vitro | PVP-I 4% PVP-I 7.5% PVP-I 1% |

Vero E6 cells were infected with MERS-CoV and HCoV-EMC/2012. The test solutions and viruses were incubated at RTa for 15, 30 and 60 s. |

All products achieved 99.99% virucidal activity at 15 s of contact. Reduction in viral titres (TCID50/mL) ≥4.00. |

| Mukherjee et at. [27] | In vivo | ARMS-I™: cetylpyridinium chloride 0.1% | Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled pilot clinical trial. Healthy adults (18–45 years) were randomized into ARMS-I™ or placebo group (50 subjects each). 94 individuals completed the study. The drug was sprayed intra-orally (3× daily) for 75 days. PCR analysis was performed on the oral and nasal swabs collected from individuals with URIs (upper respiratory infections) to determine whether ARMS-I™ decreases the detection of respiratory viruses (influenza B, coronavirus, or rhinovirus (OC43)). |

Relative decrease (55%) in URIs. PCR analysis showed the presence of influenza B, coronavirus or rhinovirus (OC43) in three participants; all in the placebo group. Fever was reported only in the placebo group. ARMS-I significantly reduced the frequency and severity of cough and sore throat, and duration of cough (P ≤ 0.019 for all comparisons). ARMS-I was safe, well tolerated, had high acceptability and high adherence to medication use. Medical visits occurred only in the placebo group. Absenteeism did not differ between the two groups. Prior influenza vaccination had no effect on study outcome. |

| Eggers et al. [28] | In vitro | PVP-I 0.23% | PVP-I was tested against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Streptococcus pneumoniae according to bactericidal quantitative suspension test EN13727. PVP-I was tested against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, rotavirus strain Wa and influenza virus A subtype H1N1 according to virucidal quantitative suspension test EN14476. The test solutions and virus were incubated at RTa for 15 s for SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, 15 and 30 s for influenza, and 15, 30, 60 and 120 s for rotavirus. |

All bacterial counts were reduced by a log10 reduction factor between >×5.20 and >×5.47 copies/mL (reduction in bacterial count of ≥99.999%) after 15 s of contact time. All viral titres were reduced by between 4.40 and 6.00 TCID50/mL (reduction in viral titres of ≥99.99%) after 15 s of contact time. |

| Kariwa et al. [29] | In vitro | Isodine solution®: PVP-I 1% Isodine Scrub®: PVP-I 1% Isodine Palm®: PVP-I 0.25% Isodine Gargle®: PVP-I 0.47% Isodine Nodo Fresh®: PVP-I 0.23% |

Hanoi strain of SARS-CoV in Vero E6 cells. The exposure of the virus to PVP-I products was performed at RTa for 60 s. |

Treatment of SARS-CoV for 60 s with Isodine Scrub, Isodine Palm, and Isodine Nodo Fresh strongly reduced the virus infectivity from 1.17×106 TCID50/mL to below the detection limit, <40 to <160. Treatment of SARS-CoV for 60 s with Isodine and Isodine Gargle did not completely eliminate the virus infectivity: 8.1×10−5 and 1.6×10−4 TCID50/mL, respectively. |

| Meyers et al. [30] | In vitro | Neti Pot, nasal rinse: sodium bicarbonate (700 mg), sodium chloride (2300) mg Johnson's Baby Shampoo, nasal rinse: water, cocamidopropyl betaine, decyl glucoside, sodium cocoyl isethionate, lauryl glucoside, PEG-80, sorbitan laurate, glycerin Peroxide Sore Mouth, oral rinse: H2O2 1.5% Orajel Antiseptic Rinse, oral rinse: H2O2 1.5%, menthol 0.1% H2O2 1.5%, oral rinse Crest Pro-Health, oral rinse: cetylpyridium chloride 0.07% Listerine Antiseptic, Listerine Ultra, Equate, Antiseptic Mouthwash, oral rinses: eucalyptol 0.092%, menthol 0.042%, methyl salicylate 0.06%, thymol 0.064%. Betadine 5%, oral rinse: PVP-I 5% |

Virus (HCoV-229e) and product were mixed thoroughly and incubated for 30 s, 1 min, or 2 min at RTa. Reductions in titres were measured by using the tissue culture infectious dose 50 (TCID50) assay in Huh7 cells. |

Neti Pot had no effect on the infectivity of the virus at any incubation time tested. With contact times of 1 and 2 min, the 1% baby shampoo solution inactivated >99% and ≥99.9% of the virus, respectively. The three products with H2O2 as their active ingredient demonstrated that reduction of infectious virus ranged from lower than a log10 reduction factor of x1 to x2 or <90%–99% at 30 s, 1 min or 2 min of contact. Crest Pro-Health decreased infectious virus by a log10 reduction factor of x3 (at 30 s or 2 min of contact), to ×4 (at 1 min of contact), or 99.9% to >99.99%. Listerine Antiseptic decreased infectious virus levels by a log10 reduction factor of ×4, or >99.99% at 30 s, 1 min or 2 min of contact. Listerine-like mouthwashes/gargles decreased infectious virus titres by >99% at 30 s, 1 min or 2 min of contact. Betadine 5% decreased infectious virus levels by a log10 reduction factor of >×4 (at 30 s of contact) or >99.99% (at 1 min or 2 min of contact). |

| Shen et al. [31] | In vitro and in vivo | Lycorine Emetine Phenazopyridine Mycophenolic acid Mycophenolate mofetil Pyrvinium pamoate Monensin sodium (cetylpyridinium chloride) |

A search for effective inhibitory agents was carried out by high-throughput screening (HTS) of a 2000-compound library of approved drugs and pharmacologically active compounds using the established genetically engineered human CoV OC43 (HCoV-OC43) strain expressing Renilla luciferase (rOC43-ns2Del-Rluc) and validated the inhibitors using multiple genetically distinct CoVs in vitro (HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, MERS-CoV, MHV-A59). Broad-spectrum anti-CoV activity was evaluated in vitro and in vivo in an experimental infection mouse model. Dose–response curves for seven broad-spectrum inhibitors of four types of CoVs in vitro. BHK-21, Vero E6, LLC-MK2, or DBT cells were infected with HCoV-OC43-WT, MERS-CoV, HCoV-NL63, or MHV-A59 at an MOI of 0.01, respectively, and treated for 72 h with eight doses (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, or 20 μM) of each product. |

56 results from the HTS data were examined and 36 compounds were validated in vitro using wild-type HCoV-OC43. Seven compounds inhibited the replication of all CoVs with EC50 values of <5 μM: lycorine, emetine, phenazopyridine, mycophenolic acid, mycophenolate mofetil, pyrvinium pamoate, and monensin sodium. Emetine blocked MERS-CoV entry according to pseudovirus entry assays, and liquorine protected BALB/c mice against HCoV-OC43-induced lethality by lowering the viral load in the central nervous system. |

PVP-I, povidone-iodine.

Room temperature: 22 ± 2°C.

Table III.

Oral antiseptics against the SARS-COV-2 virus: in-vivo and in-vitro studies

| Study | Study type | Test product | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martínez et al. [32] | In vivo | PVP-I 1% | 15 mL 1% PVP-I, 1 min rinse. Four patients with positive initial detection for SARS-CoV-2 (nasopharyngeal virus detection by PCR). Serial saliva samples: baseline, 5 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h after the rinse. Intra-oral viral load test by RT–PCR. |

In two of the four participants the PVP-I resulted in a significant fall in viral load, which remained for at least 3 h. |

| Gottsauner et al. [33] | In vivo | H2O2 1% | 20 mL 1% H2O2 30 s rinse gargling mouth and throat. 12 patients with positive initial detection for SARS-CoV-2 (nasopharyngeal virus detection by PCR). Saliva samples at baseline and 30 min after the rinse. Intra-oral viral load test performed by RT–PCR. Virus culture was performed for samples that had a viral load of ≥103 RNA copies/mL at baseline. |

No significant differences between baseline viral load and viral load 30 min after the mouth rinse (P = 0.96). Replicating virus could only be detected in one baseline specimen. |

| Yoon et al. [34] | In vivo | Chlorhexidine 0.12% | 15 mL chlorhexidine 0.12%, 30 s rinse. Two patients with positive initial detection for SARS-CoV-2 (nasopharyngeal virus detection by PCR). Saliva samples were taken: baseline, 1, 2, and 4 h after the rinse. Intra-oral viral load was determined by rRT–PCR. |

Viral load in saliva decreased (a log10 reduction factor <×3) transiently for 2 h post mouthwash, but it increased again at 2–4 h post mouthwash. |

| Seneviratne et al. [35] | In vivo | PVP-I 0.5% (Betadine® Gargle and Mouthwash 10 mg) Chlorhexidine 0.2% (Pearly White Chlor-Rinse®) CPC 0.075% (Colgate Plax mouthwash®) Sterile water |

16 patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 (nasopharyngeal virus detection by PCR), randomly assigned to four groups: PVP-I group (N = 4), CHX group (N = 6), CPC group (N = 4) and water as control group (N = 2). Saliva samples collected at baseline and at 5 min, 3 h, and 6 h post-application of mouth rinses/water. Samples subjected to SARS-CoV-2 RT–PCR analysis. |

Salivary CT values of patients within each group at 5 min, 3 h, and 6 h time-points showed no significant differences. When the CT value fold change of each of the mouth rinse group patients was compared with the fold change of water group patients at the respective time-points, a significant increase was observed in the CPC group patients at 5 min and 6 h and in the PI group patients at 6 h. |

| Bidra et al. [36] | In vitro | PVP-I 0.5%, 0.75%, 1.5% | SARS-CoV-2 (USA-WA1/2020) in Vero 76 cells. Test solutions and virus incubated at RTa for 15 and 30 s. |

Virucidal activity at 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1.5% concentrations and the shortest contact time (15 s). LRVb: 3.0. Virucidal activity at 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1.5% concentrations and the longest contact time (30 s). LRV: 3.33. |

| Anderson et al. [37] | In vitro | PVP-I 10% antiseptic solution PVP-I 7.5% skin cleanser PVP-I 1% gargle and mouthwash PVP-I 0.45% throat spray |

SARS-CoV-2 (hCoV-19/Singapore/2/2020) in Vero-E6 cells. Exposure of the virus to PVP-I products was performed at RT for 30 s. |

All four products achieved 99.99% virucidal activity at 30 s of contact. Reduction in viral titres (TCID50/mL) ≥4.00. |

| Pelletier et al. [38] | In vitro | PVP-I 0.5%, 0.75%, 1.5% oral rinse antiseptic solutions PVP-I 0.5%, 1.25%, 2.5% nasal antiseptic solutions |

SARS-CoV-2 (USAWA1/2020) in Vero 76 cells. Test solutions and virus were incubated at RT for 60 s. |

All products achieved 99.99% virucidal activity at 60 s of contact. LRV: 4.63. |

| Bidra et al. [39] | In vitro | PVP-I 0.5%, 1.25%, 1.5% H2O2 1.5%, 3% |

SARS-CoV-2 (USAWA1/2020) in Vero 76 cells. The test solutions and virus were incubated at RT for 15 and 30 s. |

Virucidal efficacy of PVP-I after 15 s: LRV >4.33 Viricudal efficacy of H2O2 after 15 s: LRV 1.00–1.33 Virucidal efficacy of PVP-I after 30 s: LRV >3.63 Virucidal efficacy of H2O2 after 30 s: LRV 1.0–1.8 |

| Gudmundsdottir et al. [40] | In vitro | ColdZyme® (CZ-MD) | SARS-CoV-2 (USAWA1/2020) in Vero E6 cells (for SARS-CoV-2), and MRC-5 cells (for HCoV-229E). | CZ-MD inactivated SARS-CoV-2 by 98.3% (TCID50/mL reduction of 1.76) and HCoV-229E by 99.9% (TCID50/mL reduction of 2.88). |

| Steinhauer et al. [41] | In vitro | Formulation A (100 g contains: 0.1 g chlorhexidine bis-(d-gluconate) Formulation B (100 g contains: 0.2 g chlorhexidine bis-(d-gluconate) Formulation C (100 g contains: 0.1 g octenidine dihydrochloride, 2 g phenoxyethanol) |

Isolated SARS-CoV-2 outbreak 100 strain, under conditions of low organic soiling (0.3 g/L bovine serum albumin; ‘clean 90 conditions’) as defined in EN 14476. | Formulation A reduced virus titre at a prolonged contact time of 10 min by a log10 reduction factor of <×1. Formulation B reduced virus titre within a contact time of 1 min and at a prolonged contact time of 5 min when tested at 80% (v/v) concentration by a log10 reduction factor of <×1. Formulation C reduced SARS-CoV-2 titres by a log10 reduction factor of x4.38 from 15 s, for both concentrations tested (80% (v/v) and 20% (v/v)). |

| Hassandarvish et al. [42] | In vitro | PVP-I 0.5% gargle and mouthwash PVP-I 1% gargle and mouthwash |

SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-COV-2/MY/UM/6-3; TIDREC) in Vero E6 cells. The test solutions and virus were incubated at RT for 15, 30, and 60 s. |

PVP-I 1% achieved a log10 reduction factor of ×5 in viral titres at 15, 30, and 60 s. PVP-I 0.5% demonstrated a log10 reduction factor in viral titres of >×4 at 15 s and >×5 at 30 and 60 s. |

PVP-I, povidone-iodine; RT–PCR, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction; CHX, chlorhexidine digluconate; CPC, cetylpyridinium chloride.

Room temperature: 22 ± 2°C.

Log10 reduction value.

The main oral antiseptics that have been tested against other coronaviruses are povidone-iodine (PVP-I) [6,[28], [29], [30]], essential oils [30,31], cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) [27,30], sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, baby shampoo, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [30].

The oral antiseptics tested against SARS-CoV-2 were PVP-I [32,[35], [36], [37], [38], [39],42], H2O2 [33,39], chlorhexidine digluconate (CHX) [34,35,41], ColdZyme® [40], and CPC [35].

Discussion

Scientific evidence available on the use of oral antiseptics against coronavirus including SARS-CoV-2

In general, it is believed that an antimicrobial mouthwash before any procedure in the oral cavity reduces the number of oral micro-organisms, although there is specifically no information available on its effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 [43,44].

In a Cochrane document prepared by scientific institutions and societies, it is concluded that 82% of the documents reviewed recommend the use of a mouthwash prior to oral intervention with the aim of reducing the viral load of aerosols [45].

The following sections describe the different manuscripts addressing the specific activity of oral antiseptics against SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses.

Povidone-iodine

Previous in-vitro studies have shown that SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV were highly susceptible to PVP-I mouthwash [28]. Therefore, preprocedural mouthwash with 0.2% PVP-I was assumed to reduce the burden of SARS-CoV-2 virus in saliva [13,43]. In other studies, agents such as H2O2 at 1% and PVP-I at 0.2% are recommended in order to reduce the salivary load of oral micro-organisms, potentially including SARS-CoV-2 [43].

The inactivation of coronavirus (e.g. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV) on surfaces by PVP-I (0.23%) has also been demonstrated [46].

In-vitro studies have shown rapid virucidal activity of PVP-I products against Ebola virus, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and the European reference virus Ankara modified vaccinia virus (MVA) [6,26,27] (Table II). PVP-I has been tested in vitro against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Streptococcus pneumoniae, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, the Wa rotavirus strain, and the influenza A subtype H1N1 virus. PVP-I 0.23% showed rapid bactericidal and virucidal activity, so the use of povidone at this concentration may provide a measure of protective oropharyngeal hygiene for individuals at high risk for exposure to oral and respiratory pathogens [28] (Table II).

In a first in-vivo study conducted in May 2020 with COVID-19-positive patients, the impact of a PVP-I 1% mouthwash on the SARS-CoV-2 viral load in saliva was analysed in four patients. In two of the four participants, PVP-I produced a significant decrease in load, which remained for at least 2 h [32] (Table III). However, no control group with an innocuous mouth rinse was included in the study, and all participants were taking antiviral drugs at the moment of sampling, making it difficult to evaluate the effect of the antiseptic in this small sample size.

Subsequently, in an in-vitro study, PVP-I was tested at diluted concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5%. Virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2 was present at the lowest concentration and at the shortest contact time (15 s). This finding may justify the use of PVP-I preprocedural mouthwash (for patients and healthcare providers) and may be useful as an adjunct to personal protective equipment for dental and surgical specialties during the COVID-19 pandemic [36] (Table III).

Later, another in-vitro work was published on the virucidal activity of PVP-I on SARS-CoV-2. The four products (antiseptic solution (PVP-I 10%), skin antiseptic (PVP-I 7.5%), gargles and mouthwash (PVP-I 1%), and throat spray (PVP-I 0.45%) reached 99.99% virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2 [37] (Table III).

Another in-vitro study evaluated nasal and oral antiseptic formulations in concentrations of 1–5% of PVP-I to determine virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2. All concentrations of nasal antiseptics and mouthwash antiseptics evaluated completely inactivated SARS-CoV-2. The authors concluded that the tested formulations could help reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 if used for nasal decontamination, oral decontamination, or surface decontamination in known or suspected cases of COVID-19 [38] (Table III).

An in-vitro work has recently been published to evaluate the virucidal activity of a povidone-iodine product (PVP-I 1% gargle and mouthwash) against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The product, undiluted and at a 1:2 dilution, demonstrated potent and rapid virucidal activity [42] (Table III).

A hospital protocol for the use of PVP-I as ‘personal protective equipment’ was published to attenuate the nosocomial transmission of COVID-19 in patients with head and neck cancer, not only for patients but also for professionals who treat them, especially in those who perform open and endoscopic surgery and upper aerodigestive procedures. Given the great penetration of nasal irrigation into the nasopharynx, they incorporate the treatment models of chronic rhinosinusitis and propose the following formulations for administration: (1) nasal irrigation: 240 mL of 0.4% PVP-I solution (dilution 10 mL of commercially available 10% aqueous PVP-I, in 240 mL of normal saline with a sinus rinse administration bottle) and (2) oral/oropharyngeal lavage: 10 mL of 0.5% aqueous PVP-I solution (1:20 dilution in sterile or distilled water). The literature supports the safety of these doses, and PVP-I concentrations can be well tolerated without mucociliary toxicity. They conclude that this protocol can be applied to healthcare professionals at risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 [47].

Hydrogen peroxide

Another antiseptic much studied and evaluated against other coronaviruses has been H2O2. In many studies, 1% agents are recommended in order to reduce the saliva load of oral micro-organisms, potentially including SARS-CoV-2. The inactivation of coronavirus (e.g. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV) on surfaces by H2O2 (0.5%) has also been demonstrated [46].

The hypothesis of antiseptic efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in the oral and nasal mucosa is supported by the use of 3% H2O2 (10 volumes) diluted 1–1.5%. The action is not only due to the well-known oxidative and mechanical elimination properties of H2O2 but also to the induction of an innate inflammatory antiviral response by overexpression of toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), which generally reduces the progression of infection from upper to lower respiratory tract. They therefore recommend the use of 3% H2O2 (10 volumes) diluted 1–1.5% for nasal and oral washes, which should be carried out immediately within the time-frame after the onset of the first symptoms and the diagnosis of infection with SARS-CoV-2, and during the period of illness, in home quarantine or hospitalized subjects who do not require intensive care. They propose a regimen of gargles three times a day for disinfection of the oral cavity and nasal washes with a nebulizer two times a day (due to increased sensitivity of the nasal mucosa). Using H2O2 on mucous membranes is as safe as a gargle or nasal spray. In fact, it is already commonly used in otorhinolaryngology. Randomized controlled trials in SARS-CoV-2-positive and -negative subjects are needed to study the benefits of 3% H2O2 (10 volumes) diluted 1–1.5% in reducing pulmonary complications and hospitalization time [48].

In another in-vitro work, the virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2 of H2O2 and PVP-I is compared. PVP-I was tested at concentrations of 0.5%, 1.25%, and 1.5%, and H2O2 was tested at concentrations of 3% and 1.5%. Ethanol and water were evaluated in parallel as positive standard and negative controls. Oral antiseptic with PVP-I in the three concentrations left SARS-CoV-2 completely inactivated at the lowest concentration of 0.5% and at the lowest contact time of 15 s, whereas H2O2 solutions showed minimal virucidal activity. Therefore, the authors conclude that preprocedural rinsing with diluted PVP-I in the range of 0.5–1.5% may be preferred over H2O2 [39] (Table III).

Another in-vivo study with twelve hospitalized patients has been published whose objective was to investigate the effects of a 1% H2O2 mouthwash on reducing the intra-oral burden of SARS-CoV-2. H2O2 mouthwash did not lead to a significant reduction in intra-oral viral load. However, viral cultures could only be obtained from one baseline sample in one of the patients, and no control group with an innocuous mouth rinse was included, limiting the interpretation of results. As clinical relevance, they indicate that the recommendation of a preprocedural H2O2 rinse before intra-oral procedures is questionable. In this context, the impact of a ‘false sense of security’ due to H2O2 mouthwash in potentially infectious patients should be considered [33] (Table III).

Chlorhexidine

In the scientific literature, CHX has been shown to have effective virucidal activity for enveloped viruses, such as herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, influenza A, parainfluenza and hepatitis B [49]. At present, there is insufficient scientific evidence on the use of CHX mouthwashes for the reduction of microbial load related to SARS-CoV-2 [43,46]. The inactivation of coronavirus (e.g. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV) on surfaces by CHX 0.02% was ineffective [46] but it has to be kept in mind that this concentration is significantly lower than the usual levels present in commercially available mouthwashes, which are typically at 0.12–0.2%.

In another work, viral dynamics were evaluated in various samples of body fluids, such as nasopharyngeal swabs, oropharyngeal swabs, saliva, sputum, and urine samples from two patients with COVID-19 from day 1 to day 9 of hospitalization. SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the five samples from both patients. The viral load was highest in the nasopharynx (patient 1: 10×8.41 copies/mL; patient 2: 10×7.49 copies/mL), but it was also notably high in saliva (patient 1: 10×6.63 copies/mL; patient 2: 10×7.10 copies/mL). SARS-CoV-2 was detected up to day 6 in the hospital (disease day 9 for patient 2) in the saliva of both patients. The viral load in saliva transiently decreased for 2 h after using chlorhexidine mouthwash [34] (Table III).

Finally, in another study, antiseptic mouthwashes based on the actives CHX and octenidine (OCT) were investigated regarding their efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 using EN 14476. The OCT-based formulation was effective within only 15 s against SARS-CoV-2, and thus constitutes an interesting candidate for future clinical studies to prove its effectiveness in a potential prevention of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by aerosols [41] (Table III).

Cetylpyridinium chloride

Among the antiseptic agents studied, CPC is the one that, according to the available scientific evidence, offers the most encouraging results. It is a quaternary ammonium salt. It has a broad spectrum of action, bactericidal and virucidal, and is usually available for oral use in concentrations of 0.02–0.07%. It is considered a detergent, its hydrophilic–lipophilic balance being approximately 15–16 [50].

This antiseptic has been described with virucidal capacity against the influenza virus. In-vitro experiments demonstrated the degradation of the lipid bilayer of the envelope of various strains of influenza virus treated with 0.005% CPC [51]. Other results in an in-vitro and in-vivo study indicate that CPC could be effective against other enveloped viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus or coronaviruses [31] (Table II).

In another clinical study, it was observed that a group of subjects who used 0.10% CPC for 75 days in an intra-oral spray format had a lower incidence of viral infections of the upper respiratory tract [27] (Table II). Therefore, it is suggested that CPC could have a preventive effect on infection by influenza virus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus and coronavirus, among others.

Therefore, CPC at 0.05–0.1% has been recommended for use as a patient rinse prior to oral treatment to reduce the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 [12].

In a recent study, the virucidal capacity of four antiseptics were compared, among them CPC, but against the HCoV-229e coronavirus, which has different pathogenicity but a similar structure, because they are from the same family and both are human respiratory pathogens. Nasal rinses and mouthwashes/gargles were tested for their ability to inactivate high concentrations of HCoV-229e. The essential oil products, PVP-I and CPC, were very effective in inactivating virus infection with a 99.9–99.99% reduction in viral load, even with a contact time of 30 s [30] (Table II).

Finally, in a randomized clinical trial, the efficacy of three commercial mouthwashes, PVP-I, CHX and CPC, in reducing the salivary viral load of SARS-CoV-2 was evaluated in COVID-19 patients compared to water. The salivary viral load decreased with CPC and PVP-I mouthwashes, and this effect was maintained at 6 h [35] (Table III). This result was very weak, as the effect was only seen when comparing CT values in the test groups relative to the two individuals in the control group, where viral load appeared to increase after the mouthwash with water. However, no significant differences were observed when comparing the viral load of each individual to their corresponding basal levels.

Other agents used as antiseptics

Finally, it has been reported that a randomized clinical trial is being conducted to compare the efficacy of 1% H2O2, 0.2% PVP-I, 2% hypertonic saline, and a Neem extract solution (Azadirachta indica) to reduce the intra-oral viral load in COVID-19-positive patients. Five groups of 10 patients each are compared, who will use mouthwashes and nasal washes with these antiseptics, and it will be seen if there is a reduction in viral load by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The study protocol is available. The results have not yet been published [52].

Several Cochrane reviews, in which the use of antimicrobials in the form of mouthwash and nasal spray is evaluated by professionals to protect themselves when treating patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 or for patients to improve the evolution of their disease, conclude that there is currently no evidence related to the benefits and risks of using antimicrobials by healthcare workers to protect themselves when treating people with COVID-19 or by patients. In addition, they warn that it is important that future studies collect and analyse information on adverse events and that it is taken into account that antiseptics can also eliminate micro-organisms from the mouth or nose that are useful to protect the body against infections [53,54].

There are also other interesting antiseptics under study, such as ColdZyme® (CZ-MD), which is a mouth spray used for the common cold [40] (Table III); Citrox (bioflavonoid) and cyclodextrins (cyclic oligosaccharides) in mouthwash [55]; or even the potential of probiotics to act against SARS-CoV-2 [56].

In another study, the efficacy against different micro-organisms of nasal washes with hypochlorous acid (HOCl) was evaluated. They treated primary human nasal epithelial cells with 3.5 ppm hypochlorous acid and then examined them for cytotoxicity. They also investigated the bactericidal, fungicidal, and virucidal effects against the following micro-organisms: Aspergillus fumigatus, Haemophilus influenzae, K. pneumoniae, Rhizopus oryzae, Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, S. pneumoniae, and S. pyogenes. To study the virucidal effects of HOCl, they used the human influenza A virus. A cytotoxicity test and the morphological examination of the cells showed no toxicity at 30 min or 2 h after treatment with HOCl. More than 99% of bactericidal or fungicidal activity was observed for all species, except for C. albicans, in tap water at pH 7.0 or 8.4. A reduction in cells exposed to human influenza A virus was achieved [57]. This product can be found for spray application for oral use, periocular area, nose or ear, although there is not enough evidence to support its oral use, so it has not been, and is not, routinely recommended with this purpose.

Recommendations on the use of oral antiseptics against the SARS-CoV-2 virus

Based on the evidence collected so far, we would recommend rinsing prior to the oral examination/treatment of the patient. It is advisable to spit the antiseptic into the disposable cup in which the product has been administered. There is no scientific evidence on the usefulness of gargling to reduce the viral load in the pharynx. In addition, anything that can stimulate coughing or sneezing should be avoided as this could generate aerosols by the patient.

The three most recommended oral antiseptics in the scientific works against SARS-CoV-2 have been PVP-I, H2O2, and CPC.

One of the most important characteristics that an oral antiseptic should have is its substantivity, that is, the time it is kept active in mouth. In the current situation, with a great risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2, this property is essential to be able to perform treatments with the maximum possible safety. There is no clear scientific evidence for the substantivity of PVP-I or H2O2. It has been reported that the microbicidal activity of PVP-I shows a reduction of 72% during 30 min after its use as a rinse [58]. The minimum time necessary for an antiseptic mouth rinse to exert its virucidal action against coronavirus has not been tested in vivo.

However, we do know that the substantivity of CPC is high, from 3 to 5 h, which would enable enhanced efficacy against the virus for a longer time.

Although CHX is an antiseptic widely used and has a very high substantivity, from 7 to 12 h, it has not been recommended as an antiseptic for use before an oral examination or procedure due to the lack of evidence of virucidal activity against coronavirus. However, Yoon et al. found SARS-CoV-2 suppression for 2 h after using 15 mL 0.12% CHX once, suggesting that its use could be beneficial for the control of COVID-19 transmission [34].

Among the requirements for antiseptics are their safety and that they do not produce undesirable effects. Both PVP-I and H2O2 have a number of risks and limitations in their oral use. According to the manufacturer, in children aged <12 years, and in adolescents, H2O2 must be administered under the supervision of an adult. Finally, it is contraindicated in case of gingival wounds. The PVP-I also has its limitations of use. According to the manufacturer, it cannot be used if the patient is allergic to PVP-I or to any of the components of the product, in case of hyperthyroidism or other acute thyroid diseases and in children aged <30 months. In oropharyngeal use, caution should be exercised to avoid aspiration into the respiratory tract as it may cause complications such as pneumonitis (important in intubated patients).

Povidone-iodine is safe in the nose up to 1.25% and mouth up to 5% for up to five and six months, respectively. Absorption of iodine is poorly described, inconsistently analysed, and without clear conclusions. Regardless, PVP-I has been demonstrated to be systemically risk-free at concentrations up to 5% daily for five months [59].

Among the available mouth rinses, CHX formulations remain undisputed as the reference standard among anti-plaque mouth rinses, but local side-effects have tended to restrict their use to the short to medium term. The most significant local side-effect of CHX is the well-known formation of extrinsic staining of teeth, oral mucosa, restorative materials, and acrylic dentures. CPC, which is perhaps the most common ingredient in over-the-counter products, may also produce dental staining [60].

Adverse effects observed with long-term use of CPC were discoloration of the teeth and tongue, and slight transient irritation of the gums and aphthous ulcers in some individuals [61].

For now, we do not believe it is convenient to recommend any antiseptic preventive to the professional prior to treating patients, as the necessary scientific support is not available. It must be taken into account that all antiseptics alter the normal oral microbiome, and we do not know how the virus can behave in an individual who uses an antiseptic continuously.

Therefore, according to the available scientific evidence, we consider it necessary and advisable to use one of the following antiseptics by the patient prior to the oral examination/treatment: CPC 0.05–0.07%, PVP-I 0.2% or H2O2 1%.

Importance of oral hygiene

An interesting study has evaluated the effects of oral care on the prolonged viral shedding of coronavirus in patients with COVID-19. They evaluated the clinical course of eight COVID-19 patients, including the duration of viral shedding, using quantitative PCR of nasopharynx swabs. Most of the patients had a viral shedding period of ≤30 days. Two of the patients had a significantly longer period of prolonged viral shedding (>44 days). When they were instructed on the importance of oral care, the PCR test result became negative. In cases of such prolonged viral shedding, non-infectious viral nucleic acid may accumulate in uncleaned niches from the oral cavity and may still be detected by PCR [62].

Finally, another study determined that risk factors, such as poor oral hygiene, coughing, increased inhalation under normal or abnormal conditions, and mechanical ventilation, provide a pathway for oral micro-organisms to enter the lower respiratory tract and therefore cause co-respiratory infection that aggravates COVID-19 disease. Pulmonary hypoxia, a typical symptom of COVID-19, would also favour the growth of an-aerobes and facultative anaerobes that originate in the oral microbiome [63].

Conclusions

There is sufficient in-vitro evidence to support the use of antiseptics to potentially reduce the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 or other coronaviruses. However, in-vivo evidence for most oral antiseptics is limited. Available in-vivo studies have extremely small sample sizes or do not include a placebo group and yield conflicting or inconclusive results. Well-designed randomized clinical trials with a control group are needed to demonstrate its clinical efficacy and are essential to clarify whether oral antiseptics might be helpful in lowering SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the following situations: one-off use prior to oral examination/procedure in asymptomatic/presymptomatic/symptomatic patients; long-term use in symptomatic COVID-19 patients to reduce the pathogen-icity of the disease and the risk of transmission and long-term use at the population level as a complementary method of oral hygiene; assessing its usefulness in asymptomatic/presymptomatic COVID-19 patients and its potential contribution to the control of the pandemic. A special focus should be placed on the importance of oral hygiene and prevention in the control of COVID-19.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding sources

None.

References

- 1.Meng L., Hua F., Bian Z. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034520914246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mateos M.V., Lenguas A.L., Pastor V., García I., García M.T., García G., et al. Odontología en entorno COVID-19. Adaptación de las Unidades de Salud Bucodental en los centros de salud de la Comunidad de Madrid. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2020;94:12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33174539 de noviembre e202011148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohan S.V., Hemalatha M., Kopperi H., Ranjith I., Kumar A.K. SARS-CoV-2 in environmental perspective: occurrence, persistence, surveillance, inactivation and challenges. Chem Eng J. 2021;405:126893. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fathizadeh H., Maroufi P., Momen-Heravi M., Dao S., Köse Ş., Ganbarov K., et al. Protection and disinfection policies against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Le Infez Med. 2020;28:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q., Liu X.L., Zhuang Z.X., Cheung C.L., et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China. Science. 2003;302(5643):276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggers M., Eickmann M., Zorn J. Rapid and effective virucidal activity of povidone-iodine products against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s40121-015-0091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitworth J. COVID-19: a fast evolving pandemic. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020;114:241–248. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/traa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of 2019-nCoV – a quick overview and comparison with other emerging viruses. Microb Infect. 2020;22:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou P., Lou Yang X., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K., Chu H., Yang J., et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C., et al. Transmission of 2019-NCOV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izzetti R., Nisi M., Gabriele M., Graziani F. COVID-19 transmission in dental practice: brief review of preventive measures in Italy. J Dent Res. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0022034520920580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ather A., Patel B., Ruparel N.B., Diogenes A., Hargreaves K.M. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. 2020;46:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H., Zhong L., Deng J., Peng J., Dan H., Zeng X., et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakaguchi W., Kubota N., Shimizu T., Saruta J., Fuchida S., Kawata A., et al. Existence of SARS-CoV-2 entry molecules in the oral cavity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6000. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W.K., Chen S.Y., Liu I.J., Chen Y.C., Chen H.L., Yang C.F., et al. Detection of SARS-associated coronavirus in throat wash and saliva in early diagnosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1213–1219. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.031113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.To K.K.W., Tsang O.T.Y., Chik-Yan Yip C., Chan K.H., Wu T.C., Chan J.M.C., et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:841–843. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J., Li Y., Gan F., Du Y., Yao Y. Salivary glands: potential reservoirs for COVID-19 asymptomatic infection. J Dent Res. 2020;99:989. doi: 10.1177/0022034520918518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabino-Silva R., Jardim A.C.G., Siqueira W.L. Coronavirus COVID-19 impacts to dentistry and potential salivary diagnosis. Clin Oral Invest. 2020;24:1619–1621. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03248-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kowalski L.P., Sanabria A., Ridge J.A., Ng W.T., de Bree R., Rinaldo A., et al. COVID-19 pandemic: effects and evidence-based recommendations for otolaryngology and head and neck surgery practice. Head Neck. 2020;42:1259–1267. doi: 10.1002/hed.26164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hormati A., Ghadir M.R., Zamani F., Khodadadi J., Afifian M., Ahmadpour S. Preventive strategies used by GI physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;35:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu R., Cui B., Duan X., Zhang P., Zhou X., Yuan Q. Saliva: potential diagnostic value and transmission of 2019-nCoV. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:11. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hormati A., Ghadir M.R., Foroghi Ghomi S.Y., Afifian M., Khodadust F., Ahmadpour S. Can increasing the number of close contact lead to more mortality in COVID-19 infected patients? Iran J Public Health. 2020;49:117–118. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v49is1.3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrera D., Serrano J., Roldán S., Sanz M. Is the oral cavity relevant in SARS-CoV-2 pandemic? Clin Oral Invest. 2020;24:2925–2930. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukherjee P.K., Esper F., Buchheit K., Arters K., Adkins I., Ghannoum M.A., et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the safety and effectiveness of a novel dual-action oral topical formulation against upper respiratory infections. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:74. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eggers M., Koburger-Janssen T., Eickmann M., Zorn J. In vitro bactericidal and virucidal efficacy of povidone-iodine gargle/mouthwash against respiratory and oral tract pathogens. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s40121-018-0200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kariwa H., Fujii N., Takashima I. Inactivation of SARS coronavirus by means of povidone-iodine, physical conditions and chemical reagents. Dermatology. 2006;212:119–123. doi: 10.1159/000089211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyers C., Robison R., Milici J., Alam S., Quillen D., Goldenberg D., et al. Lowering the transmission and spread of human coronavirus. J Med Virol. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen L., Niu J., Wang C., Huang B., Wang W., Zhu N., et al. High-throughput screening and identification of potent broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronaviruses. J Virol. 2019;93 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00023-19. e00023-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez Lamas L., Diz Dios P., Pérez Rodríguez M.T., Del Campo P., Cabrera Alvargonzalez J.J., López Domínguez A.M., et al. Is povidone-iodine mouthwash effective against SARS-CoV-2? First in vivo tests. Oral Dis. 2020;2 doi: 10.1111/odi.13526. 10.1111/odi.13526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottsauner M.J., Michaelides I., Schmidt B., Scholz K.J., Buchalla W., Widbiller M., et al. A prospective clinical pilot study on the effects of a hydrogen peroxide mouthrinse on the intraoral viral load of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Oral Invest. 2020;24:3707–3713. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03549-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon J.G., Yoon J., Song J.Y., Yoon S.Y., Lim C.S., Seong H., et al. Clinical significance of a high SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the saliva. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e195. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seneviratne C., Balan P., Kwan K.K., Udawatte N.S. Efficacy of commercial mouth-rinses on SARS-CoV-2 viral load in saliva: randomized control trial in Singapore Chaminda. Infection. 2020;1–7 doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01563-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bidra A.S., Pelletier J.S., Westover J.B., Frank S., Brown S.M., Tessema B. Rapid in-vitro inactivation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) using povidone-iodine oral antiseptic rinse. J Prosthodont. 2020;29:529–533. doi: 10.1111/jopr.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson D.E., Sivalingam V., Kang A.E.Z., Ananthanarayanan A., Arumugam H., Jenkins T.M., et al. Povidone-iodine demonstrates rapid in vitro virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19 disease. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:669–675. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00316-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pelletier J.S., Tessema B., Frank S., Westover J.B., Brown S.M., Capriotti J.A. Efficacy of povidone-iodine nasal and oral antiseptic preparations against severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Ear Nose Throat J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0145561320957237. 145561320957237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bidra A.S., Pelletier J.S., Westover J.B., Frank S., Brown S.M., Tessema B. Comparison of in vitro inactivation of SARS CoV-2 with hydrogen peroxide and povidone-iodine oral antiseptic rinses. J Prosthodont. 2020;29:599–603. doi: 10.1111/jopr.13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gudmundsdottir Á., Scheving R., Lindberg F., Stefansson B. Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and HCoV-229E in vitro by ColdZyme®, a medical device mouth spray against the common cold. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1792–1795. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinhauer K., Meister T.L., Todt D., Krawczyk A., Paßvogel L., Becker B., et al. Comparison of the in vitro-efficacy of different mouthwash solutions targeting SARS-CoV-2 based on the European Standard EN 14476. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.25.354571. 2020.10.25.354571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hassandarvish P., Tiong V., Mohamed N.A., Arumugam H., Ananthanarayanan A. In vitro virucidal activity of povidone iodine gargle and mouthwash against SARS-CoV-2: implications for dental practice. Br Dent J. 2020;10:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2402-0. https://doi.org/10.1038%2Fs41415-020-2402-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng X., Xu X., Li Y., Cheng L., Zhou X., Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood A., Payne D. The action of three antiseptics/disinfectants against enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. J Hosp Infect. 1998;38:283–295. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(98)90077-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarkson J., Ramsay C., Richards D., Robertson C., Aceves-Martins M., on behalf of the CoDER Working Group Aerosol generating procedures and their mitigation in international dental guidance documents – a rapid review. Cochrane Oral Health. 2020 July https://oralhealth.cochrane.org/news/aerosol-generating-procedures-and-their-mitigation-international-guidance-documents Available at: [last accessed April 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kampf G., Todt D., Pfaender S., Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mady L.J., Kubik M.W., Baddour K., Snyderman C.H., Rowan N.R. Consideration of povidone-iodine as a public health intervention for COVID-19: utilization as “personal protective equipment” for frontline providers exposed in high-risk head and neck and skull base oncology care. Oral Oncol. 2020;105:104724. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caruso A.A., Del Prete A., Lazzarino A.I., Capaldi R., Grumetto L. May hydrogen peroxide reduce the hospitalization rate and complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;22:1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baqui A.A., Kelley J.I., Jabra-Rizk M.A., Depaola L.G., Falkler W.A., Meiller T.F. In vitro effect of oral antiseptics on human immunodeficiency virus-1 and herpes simplex virus type 1. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:610–616. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028007610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Proverbio Z.E., Bardavid S.M., Arancibia E.L., Schulz P.C. Hydrophile–lipophile balance and solubility parameter of cationic surfactants. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2003;214:167–171. doi: 10.1016/S0927-7757(02)00404-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Popkin D.L., Zilka S., Dimaano M., Fujioka H., Rackley C., Salata R., et al. Cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) exhibits potent, rapid activity against influenza viruses in vitro and in vivo. Pathog Immun. 2017;2:252–269. doi: 10.20411/pai.v2i2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan F.R., Kazmi S.M.R., Iqbal N.T., Iqbal J., Ali S.T., Abbas S.A. A quadruple blind, randomised controlled trial of gargling agents in reducing intraoral viral load among hospitalised COVID-19 patients: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:785. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04634-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burton M.J., Clarkson J.E., Goulao B., Glenny A.-M., McBain A.J., Schilder A.G.M., et al. Antimicrobial mouthwashes (gargling) and nasal sprays to protect healthcare workers when undertaking aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs) on patients without suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;(9):CD013628. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013628.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burton M.J., Clarkson J.E., Goulao B., Glenny A.-M., McBain A.J., Schilder A.G.M., et al. Use of antimicrobial mouthwashes (gargling) and nasal sprays by healthcare workers to protect them when treating patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;(9):CD013626. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013626.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carrouel F., Conte M.P., Fisher J., Gonçalves L.S., Dussart C., Llodra J.C., et al. COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of mouthrinses with β-cyclodextrin combined with Citrox in preventing infection and progression. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1126. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tiwari S.K., Dicks L.M.T., Popov I.V., Karaseva A., Ermakov A.M., Suvorov A., et al. Probiotics at war against viruses: what is missing from the picture? Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1877. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim H.J., Lee J.G., Kang J.W., Cho H.J., Kim H.S., Byeon H.K., et al. Effects of a low concentration hypochlorous acid nasal irrigation solution on bacteria, fungi, and virus. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1862–1867. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817f4d34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaur R., Singh I., Vandana K.L., Desai R. Effect of chlorhexidine, povidone iodine, and ozone on microorganisms in dental aerosols: randomized double-blind clinical trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25:160–165. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.135910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frank S., Capriotti J., Brown S.M., Tessema B. Povidone-iodine use in sinonasal and oral cavities: a review of safety in the COVID-19 era. Ear. Nose Throat J. 2020;99:586–593. doi: 10.1177/0145561320932318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sheen S., Addy M. An in vitro evaluation of the availability of cetylpyridinium chloride and chlorhexidine in some commercially available mouthrinse products. Br Dent J. 2003;194:207–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lobene R.R., Kashket S., Soparkar P.M., Shloss J., Sabine Z.M. The effect of cetylpridinium chloride on human plaque bacteria and gingivitis. Pharmacol Ther Dent. 1979;4:33–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warabi Y., Tobisawa S., Kawazoe T., Murayama A., Norioka R., Morishima R., et al. Effects of oral care on prolonged viral shedding in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Spec Care Dent. 2020;40:470–474. doi: 10.1111/scd.12498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bao L., Zhang C., Dong J., Zhao L., Li Y., Sun J. Oral microbiome and SARS-CoV-2: beware of lung co-infection. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1840. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]