Abstract

Background:

Adult drug courts are growing in popularity within the Unites States, but the quality of substance use treatment within drug court programs and the impact of drug courts on health and substance use treatment outcomes is largely unknown. We appraised the quality of United States adult drug court process evaluations and the inclusion of measures of substance use treatment quality.

Methods:

We systematically reviewed the adult drug court evaluations between 2008 and 2018 in accordance with recommended strategies for systematic grey literature search. We appraised evaluation quality using the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordination Center tool for process evaluations. We extracted recommended measures of substance use treatment quality, including measures related to screening and monitoring, diagnosis, service availability, service utilization, and outcomes.

Results:

Our search identified 112 evaluations. Process measures were included within 68 evaluations, 45% of which had poor data reliability. We found that less than 10% of evaluations reported substance use treatment quality measures related to service utilization, overdose, and mortality, while more than 75% contained criminal justice measures, including program graduation (completion of criminal justice proceedings) and participant recidivism.

Conclusions:

We found low uptake of measures of substance use treatment quality. The absence of data call into question the ability of drug courts to stem harmful substance use related health outcomes.

Keywords: Drug courts, evaluation, treatment quality, substance use disorders

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, half-million people are in prison or jail for drug-related crimes (Wagner & Sawyer, 2019). Adult drug courts have been proposed as a way to reduce incarceration among people with substance use disorders by integrating substance use treatment into court settings (Meyer et al., 1997). While variation exists among programs, adult drug courts generally divert individuals from traditional criminal justice proceedings to a court-supervised treatment program after entry of a guilty plea, while a minority of courts divert pre-plea. (Schleifer et al., 2018). A judge then monitors an individual’s progress during court proceedings with input from prosecutors, defense attorneys, probation and parole officers, and treatment providers. Substance use treatment services are often provided via a partnership with one or more community substance use treatment providers (Meyer et al., 1997). The majority of adult drug courts accept adults accused of non-violent crimes committed in the context of substance use and aim to provide them access to a continuum of substance use care as according to the National Association of Drug Court Professionals ten key components of drug courts (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1996; Meyer et al., 1997).

Since the introduction of adult drug courts in the United States in 1989, they have expanded to over 1,500 courts in 56% of counties in the United States (Marlowe & Hardin, 2016; Office of Justice Programs, 2020). The 2017 President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis called for the further expansion of drug courts in the United States, and the 2018 federal budget included a 50% increase in funding for drug courts to $165 million (Christie et al., 2017; NADCP, 2018).

The effectiveness of adult drug courts has been measured in terms of impact on participant recidivism or return to the criminal justice system. Previous meta-analyses found drug courts were associated with reduced recidivism, but also found few studies were rigorously designed (Mitchell et al., 2012; Shaffer, 2011). While there is ongoing debate about the interpretation of this research (Joanna Csete & Tomasini-Joshi, 2015; Marlowe & Hardin, 2016; Schleifer et al., 2018), it demonstrates the existence of over 150 independent studies on adult drug courts and recidivism. In contrast, the quality of substance use treatment within drug court programs and the impact of drug courts on health and substance use treatment outcomes is largely unknown. A recent study of participants randomly assigned to adult drug court or traditional adjudication in Baltimore found no difference in substance use related mortality after 15 years (Kearley et al., 2019). Peer-reviewed studies have shown low uptake of key treatment modalities, like medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) among drug court programs (Krawczyk et al., 2017; Matusow et al., 2013; Schleifer et al., 2018), leading the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) in 2015 to require access to MOUD for federal drug court grant funding (Merlowe et al., 2016).

However, these studies miss the vast majority of evaluations that have not been published in peer-reviewed literature. Since 2002, adult drug courts participating in the BJA Discretionary Grant Program (a minority of drug courts) have been mandated to conduct evaluations of program performance and state and local funding agencies may also mandate evaluation to ensure effective use of public funds (Sacco, 2018). Peer-review of these evaluations prior to dissemination has not been recommended (Heck, 2006; Rubio et al., 2008). These evaluations for government agencies create a body of grey literature on adult drug courts or literature outside of peer-reviewed or commercially published literature (Mahood et al., 2014). A previous meta-analysis of drug court impact on recidivism found over two thirds of evaluations were not peer-reviewed, despite not employing a systematic strategy to examine the grey literature (Shaffer, 2011). This grey literature guides programmatic and funding decisions related to adult drug courts at federal, state, and local agencies and the design of these evaluations may reflect the priorities of these agencies. Criminal justice agencies aim to promote public safety and punish people who break the law, and these priorities may conflict with the health promotion aims of public health and medical agencies. Criminal justice agencies may be reluctant or lack the expertise to effectively integrate substance use treatment quality measures into program evaluation. Previous United States Government Accountability Office reports raised concerns about the quality of drug court evaluations (Ekstrand, 2002, 2005). In response the National Institute of Justice, BJA, and the National Drug Court Institute (NDCI) formed an expert panel to improve drug court evaluation and the panel recommended all evaluations include measures of treatment services delivered to clients (called units of service) (Hardin & Kushner, 2008; Heck, 2006; Rubio et al., 2008; Sacco, 2018). The recommendations established best practices for drug court evaluation, but they were not tied to drug court program funding. A 2011 Government Accountability Office report noted improved evaluation of impact on recidivism did not examine results related to units of service measures for substance use treatment (Maurer, 2011). Therefore, we systematically reviewed the grey literature to appraise the quality of adult drug court process evaluations and the inclusion of substance use treatment outcomes. Incorporation of these measures are needed to monitor access and utilization of key substance use treatment modalities within adult drug courts and ensure drug court clients receive an adequate standard of care.

METHOD

We completed an environmental scan of publicly available adult drug court evaluations published between January 1, 2008 and July 1, 2018. We selected 2008 to start our scan in order to capture evaluations published after the publication of the 2006 NDCI recommendations on drug court evaluation and quality improvement and the 2008 National Center for State Courts State Wide Technical Assistance Bulletin on performance measurement of drug courts (Hardin & Kushner, 2008; Heck, 2006; Rubio et al., 2008). Given our focus on adult drug court grey literature, we did not include studies from academic databases such as Web of Science or PsycInfo. We excluded evaluations of other problem-solving court types (i.e. tribal courts, family court, or veteran courts which serve different populations and differ in program structure), evaluations not presenting original data, and evaluations of programs outside of the United States. Among evaluations reported annually, only the most recent evaluation was included. Adult drug court evaluations have two forms: 1) process evaluations documenting court workings and the services provided to clients including substance use treatment and 2) outcome evaluations examining if drug courts achieve their aims, such as reduced recidivism or improved client health (Heck, 2006). To establish our search strategy prior to conducting our research, we registered our study protocol on Open Science Framework (Appendix 1). Two changes to this protocol were made prior to our search: 1) we included studies published after January 1, 2008 rather than January 1, 2011 to ensure inclusion of studies published after NDCI and National Center for State Courts recommendations and 2) we included all evaluations regardless of funding source to avoid exclusion of evaluations completed without government funding.

In accordance with recommended strategies for environmental scans of the grey literature, (Godin et al., 2015; Porterfield et al., 2012) we first completed structured Google searches designed by the research librarian on our team identifying drug court evaluations. We conducted 51 google searches using concept terms for drug court and evaluation (Appendix 2). Because Google ranks search results by location, the search consisted of one general search, and one search for each state within the United States. Upon running a google search, the first 20 results were reviewed. If a potential evaluation was identified in this set of results, then the next 20 results were reviewed. If another potential evaluation was identified, then the next 20 results were reviewed until no additional potential evaluations were identified. Second, we completed hand searches of subject area websites (Table 1). Third, we consulted topic experts (53 drug court representatives in each US state and territory plus 12 academic experts) to identify additional evaluations. Topic experts were asked to share any original data evaluating substance use treatment within adult drug courts. Topic experts included authors of drug court evaluations or representatives from a national drug court stakeholder organization (i.e. National Association of Drug Court Professionals or the National Center for State Courts). State drug court representatives were the designated contact for drug court related inquires identified by the National Association of Drug Court Professionals. We contacted drug court representatives within these territories given criminal justice agencies may have previously elected not disseminate all relevant data.

Table 1:

Organizational subject area websites included within the environmental scan of adult drug court evaluations

| Type of Organization | Organizationa |

|---|---|

| Government Agencies | US Justice Department Bureau of Justice Statistics US Justice Department Bureau of Justice Assistance US Government Accountability Office National Institute of Justice Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration State Justice Departments State Health Departments |

| Public organizations | Bureau of Justice assistance Drug Court Technical Assistance/Clearing House Project – American University Urban Institute – Justice Policy Center National Association of Drug Court Professionals Center of Court Innovation Brookings Institute National Drug court Institute Washington State Institute for Public Policy Rand Corporation Macarthur Foundation Treatment Research Institute National Center for State Courts Abt Associates Mathematica Policy Research Council of State Governments |

The listed organization websites were each hand searched during the second step of the search for adult drug court evaluations.

Two team members reviewed identified evaluations to determine eligibility for inclusion. First, evaluations were excluded by review of the title, summary, or abstract. Then full-length evaluations were reviewed to determine final inclusion status. Disagreements were resolved by reviewing the evaluation together and reaching consensus.

Among included evaluations, two team members appraised process evaluation quality using the Cochrane recommended Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordination Center (EPPI-Center) tool for process evaluations (Cargo et al., 2018; Shepherd et al., 2010). This eight-item EPPI-Center tool classifies the reliability of process evaluation findings as low, medium, or high based on factors such as appropriateness of the study sampling, data collection, and analysis methods (Appendix 3). We extracted measures of substance use treatment quality (Table 2), including measures related to screening and monitoring (i.e. urine drug screen), diagnosis (i.e. substance use disorder diagnosis), service availability (i.e. availability of MOUD and medications for alcohol use disorder), service utilization (i.e. utilization of MOUD and medications for alcohol use disorder), and outcomes (i.e. overdose deaths). Specifically, we included measures recommended by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the NDCI, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the American Society of Addiction Medicine. Two research team members evaluated the reliability and extracted measures from each evaluation and disagreements were resolved by reviewing the evaluation with the first author to reach consensus.

Table 2:

Measures of substance use treatment quality extracted from adult drug court evaluations

| Type of measure | Measure namea | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Process measuresb | ||

| General | Treatment organization | Type of partnering treatment organization(s) |

| Treatment provider discipline | Discipline of partnering healthcare provider(s) | |

| Screening and monitoring | Social needs assessment | Screening for social needs (i.e. housing or employment) |

| Mental health disorder screening | Mental health disorder screening | |

| Unhealthy substance use screening | Unhealthy substance use screening | |

| Substance use laboratory testing | Substance use laboratory testing (i.e. urine drug screen) | |

| Diagnosis | Mental health disorder diagnosis | Mental health disorder diagnosis (i.e. depression) |

| SUD diagnosis | SUD diagnosis (i.e. cocaine use disorder) | |

| Service availability | Psychosocial treatment options | Psychosocial treatment options (i.e. cognitive behavioral therapy) |

| Availability of MAUDc | Availability of Acamprosate, naltrexone, or disulfiram | |

| Availability of MOUDc | Availability of methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone | |

| Service utilization | Social interventions delivered | Connection to housing, employment or other services |

| Psychosocial treatment delivered | Utilization of psychosocial treatment | |

| Utilization of MAUD | Utilization of Acamprosate, naltrexone, or disulfiram | |

| Utilization of MOUD | Utilization of methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone | |

| Duration of medication treatment | Length of receipt of MOUD or MAUD | |

| Connection to primary care | Frequency or portion connected to primary care services | |

| Outcome measuresb | ||

| Program graduation rate | Rate of court program completion | |

| Recidivism | Rate of recidivism | |

| All-cause mortality | Participant all-cause mortality | |

| Overdose deaths | Participant drug overdose deaths | |

| Retention in care after graduation | Utilization of treatment services after completion |

Measures were selected from the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, the National Drug Court Institute, the 2014 American Society of Addiction Medicine performance measures and the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation review of MAT guidelines.

Process measures document court workings and the services provided to clients including substance use treatment and outcome measures examine if drug courts achieve their aims, such reduced recidivism or improved client health.

MAUD = medications for alcohol use disorder, MOUD = medications for opioid use disorder

We assumed that evaluations included all drug court measures collected and that no reporting, in any form, meant that the measure was not collected. Frequency of quality measures were analyzed descriptively, and the frequency of measures related to screening and monitoring were compared to the frequency of measures related to diagnosis, availability of services, and utilization of services using a chi-squared test. All hypothesis tests were two-sided. We completed our analyses in Stata 16 (StataCorp, College Station, Tx).

RESULTS

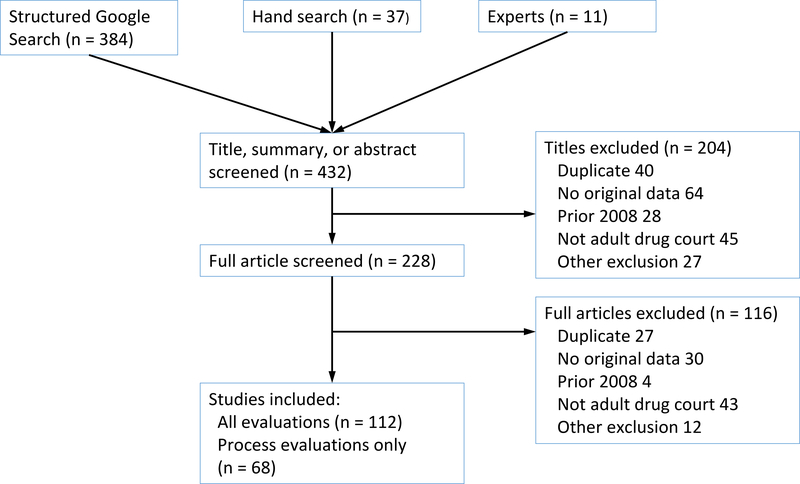

Our search identified 432 evaluations (384 via Google, 37 via hand search, and 11 via experts), of which 112 were included (excluded evaluations included 32 published prior to 2008, 67 duplicates, 88 evaluations of other problem-solving courts, 94 without original data, and 39 for other exclusions)(Figure 1). Among all evaluations, the median year of publication was 2012. Federal government agencies provided the funding for 30 (27%) of evaluations, while 74 (66%) of evaluations were completed by non-profit or for-profit organizations. Evaluations were most frequently of one adult drug court and were located on either a state government or non-profit organization website (Table 3). A list of all included evaluations is in Appendix 4.

Figure 1:

Environmental scan consisted of three steps: 1) structured Google searches, 2) subject area website hand searches, and 3) consultation with topic experts

Table 3:

Characteristics of adult drug court evaluations published between January 2008 and July 2018

| Characteristic | All evaluationsa, n = 112 | Process evaluationsb, n = 68 |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication, median (IQRc) | 2012 (2010, 2015) | 2012 (2010, 2015) |

| Funding agency, n (%) | ||

| Federal government | 30 (27) | 18 (26) |

| State government | 57 (51) | 36 (53) |

| County/municipal | 10 (9) | 8 (12) |

| Other | 15 (13) | 6 (9) |

| Evaluating agency, n (%) | ||

| Federal government | 6 (5) | 3 (4) |

| State government | 25 (22) | 16 (24) |

| Non-profit or academic | 48 (43) | 21 (31) |

| For profit | 26 (23) | 24 (35) |

| Other | 7 (6) | 4 (6) |

| Study sample, n (%) | ||

| One court | 49 (44) | 27 (40) |

| State sample 2 to 14 courts | 32 (29) | 23 (34) |

| State sample >14 courts | 21 (19) | 14 (21) |

| Regional sample 2 to 47 states | 6 (5) | 2 (3) |

| National sample >47 states | 4 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Location of evaluation, n (%) | ||

| State government website | 39 (35) | 31 (46) |

| Federal government website | 7 (6) | 3 (4) |

| Non-profit or academic website | 39 (35) | 14 (21) |

| For profit organization website | 11 (10) | 9 (13) |

| Other | 16 (14) | 11 (16) |

Includes both outcome and process evaluations.

Includes all evaluations with process measures. “Location of evaluation” represents the location of the evaluation at the time it was first identified by the authors.

IQR = interquartile range

Process measures were included within 68 evaluations, of which 37 (55%) were of medium or high reliability. Primary factors limiting the quality of process evaluations included absence of the perspective of program participants and providing no description of the approach to data analysis. Almost 80 percent of evaluations describe the data collected, but half relied on only one source of data (intervention provider, court administrative documents, or court participants). Intervention providers were the most common source of data, n = 45 (66%).

Among all evaluations containing process measures (n = 68), a minority reported the type of treatment organization or discipline of the healthcare provider (Table 4). Process evaluations reported 57% of measures related to screening and monitoring. Measures related to diagnosis (16%, p <.001), availability of services (23%, p <.001), and utilization of services (9%, p <.001) were each present at a lower frequency relative to measures of screening and monitoring. Measures related to utilization of services had the lowest frequency of reporting.

Table 4:

Measures of substance use treatment quality extracted from adult drug court evaluations published between January 2008 and July 2018

| Type of measurea | Measure name | Presence of measureb, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Process measures (n = 68) | ||

| General | Treatment organization | 32 (47) |

| Treatment provider discipline | 11 (16) | |

| Screening and monitoring | Social needs assessment | 39 (57) |

| Mental health disorder screening | 35 (51) | |

| Unhealthy substance use screening | 36 (53) | |

| Substance use laboratory testing | 45 (66) | |

| Diagnosis | Mental health disorder diagnosis | 8 (12) |

| SUD diagnosis | 14 (21) | |

| Availability of services | Psychosocial treatment options | 23 (34) |

| Availability of MAUDc | 6 (9) | |

| Availability of MOUDc | 17 (25) | |

| Utilization of services | Social interventions delivered | 21 (31) |

| Psychosocial treatment delivered | 6 (9) | |

| Utilization of MAUD | 0 (0) | |

| Utilization of MOUD | 5 (7) | |

| Duration of medication treatment | 1 (1) | |

| Connection to primary care | 2 (3) | |

| Outcome measures (n = 112) | ||

| Program graduation rate | 98 (79) | |

| Recidivism | 95 (77) | |

| All-cause mortality | 1 (1) | |

| Overdose deaths | 2 (2) | |

| Retention in care after graduation | 7 (6) |

Measures were selected from the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, the National Drug Court Institute, the 2014 American Society of Addiction Medicine performance measures and the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation review of MAT guidelines

We assumed that evaluations included all drug court measures collected and that no reporting, in any form, meant that the measure was not collected

MAUD = medications for alcohol use disorder, MOUD = medications for opioid use disorder

There was wide variation in the type of data collected by process evaluations, exemplified by the data collected for substance use disorder screening and diagnosis. Among 36 evaluations reporting on substance use disorder screening, 19 just reported that substance use disorder screening was available. A minority of evaluations reported on the specific methods used for substance use disorder screening (i.e. professional judgement, Texas Christian University drug screen, Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory, Nebraska Simple Screening Instrument). Two statewide examinations of drug courts provided data on the utilization of screening (79% of drug courts in Idaho completed substance use disorder screening and 83% of drug courts in Colorado used a standardized substance use disorder screening instrument) (Carey et al., 2012; Owens, 2014). The 2011 Multi-site adult drug court evaluation found that 88% of drug courts included clinical assessments as part of drug court eligibility and 60% of drug courts used the Addiction Severity Index for screening, while 20% used an instrument designed by drug court staff (Zweig et al., 2011).

A similar pattern was observed among the 14 evaluations reporting on substance use disorder diagnosis. Seven evaluations reported substance use disorder assessment and diagnosis was available. A statewide evaluation of Colorado drug courts reported 88% of courts complete a substance use disorder assessment (Carey et al., 2012). An evaluation of drug courts in Texas found drug court participants were more likely to receive a substance use disorder assessment relative to a matched group of individuals undergoing traditional criminal justice adjudication (Prins et al., 2015). Finally, among Michigan drug courts, 98% of participants had a substance use disorder diagnosis (White & Kunkel, 2017).

Among all evaluations containing outcomes measures (n = 112), over 75% reported a measure of court program graduation and recidivism, while only a minority (<10%) reported a measure of all-cause mortality, overdose deaths, or retention in care after program graduation (Table 4). Only one study provided data on the rate of overdose death (2 overdose deaths among 29 participants)(Christensen et al., 2016), while another study documented the occurrence of overdose deaths among the courts under evaluation.

DISCUSSION

We systematically reviewed grey literature evaluations of adult drug courts within the United States from 2008 to 2018 and found low uptake of measures of substance use treatment quality, despite recommendations by the NDCI and the expansion of adult drug courts nationally. Substance use treatment quality measures related to service utilization, overdose death, and mortality were present in less than 10% of evaluations and stand in contrast to the greater than 75% uptake of criminal justice outcome measures related to court program graduation and participant recidivism. These results suggest adult drug court expansion and funding in the absence of high-quality data on participants’ access to substance use treatment and the success of drug courts to stem the harmful health outcomes of substance use disorders. Adult drug court evaluations incorporating the perspective of people with substance use disorders and data on drug overdose death are urgently needed to ensure the health of people with substance use disorders in these court programs.

These results are consistent with previous United States Government Accountability Office reports which raised concerns about the quality of drug court evaluations and called for improvements in accordance with the academic recommendations (Ekstrand, 2002, 2005; Maurer, 2011). These results suggest despite NDCI recommendations, uptake of units of service measures related to substance use treatment quality lag behind the uptake of the other recommended categories of measures, including court program graduation (completion of court mandated treatment), sobriety (urine drug screens), and recidivism. The lack of sufficient monitoring of substance use treatment quality within adult drug courts is concerning given previous reports raising concerns about the failure to provide a minimum standard of substance use care to court clients and criticism of a court structure which results in treatment decisions being directed by criminal justice officials rather than an independent healthcare provider (Joanne Csete & Wolfe, 2017; Mollman & Mehta, 2017; Schleifer et al., 2018).

These results examining the reporting of substance use treatment quality within the adult drug court grey literature are consistent with previous examinations of peer-reviewed literature (Krawczyk et al., 2017; Matusow et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2012; Shaffer, 2011). Shaffer’s 2011 meta-analysis on recidivism found 41 grey literature drug court evaluations. Upon utilization of a systemic approach to the identification of grey literature, this study identified 112 evaluations further establishing the unique importance non-peer-reviewed evaluations play in this field. The high count and frequency of grey literature evaluations containing a measure of recidivism is consistent with previous systematic reviews which found a large body of literature examining recidivism and together demonstrate a prioritization of this measure (Mitchell et al., 2012; Shaffer, 2011). Previous research raised concerns about the quality of substance use disorder screening and assessment within adult drug courts (Mollman & Mehta, 2017), and only one in five reviewed evaluations documented if a diagnosis was completed, suggesting inadequate oversight. Previous peer-reviewed studies demonstrated less than half of adult drug courts provide access to opioid agonist medications (buprenorphine and methadone) and participants in adult drug courts have reduced odds of receiving MOUD relative to people with OUD within the community (Krawczyk et al., 2017; Matusow et al., 2013). Results showing a low frequency of measures related to service utilization, including measures of MOUD and medications for alcohol use disorder, suggest a lack of prioritization of these measures among agencies commissioning or designing these evaluations. Future implementation and facilitation research should examine the barriers to utilization of the recommended measures of substance use disorder treatment quality within adult drug courts. Barriers such as lack of expertise, limited data collection resources, and beliefs that criminal justice agencies should not be involved with health promotion should be examined as possible targets for implementation interventions (Zielinski et al., 2020).

The limited evaluation of substance use treatment quality exists despite over a decades-long effort to promote access to MOUD within adult drug court programs by the NDCI, the BJA, and the SAMHSA (Hardin & Kushner, 2008; Merlowe et al., 2016). Our results suggest most drug court evaluations are not addressing these concerns. One reason may be because only one third of evaluations were funded by federal agencies. The BJA has previously leveraged federal funds in an attempt to shape local drug court programing. In 2015, the BJA announced courts could not receive discretionary grant funding if they denied access to a drug court program because a patient was receiving a MOUD (Merlowe et al., 2016). BJA and other federal agencies could similarly make funding support contingent on inclusion of key measures of substance use treatment quality within evaluations. However, these results illustrate the limitations of leveraging federal funding to shape drug court evaluation as a majority of the adult drug court evaluations were completed without federal funds. There are emerging alternatives to drug courts, such as the Seattle Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program and the Eugene Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) program, which divert individuals prior to entry into a court program. State and local agencies should include measures of substance use treatment quality within future drug court evaluations to determine the best use of taxpayer dollars relative to these emerging alternatives (LEAD National Support Bureau, 2017; White Bird Clinic, 2020).

Finally, over 40% of the process evaluations examined in our study were determined to be of low quality. An identified source of potential bias was the frequent reliance on only intervention providers for evaluation data The quality of evaluations could be improved by collecting data from multiple perspectives, particularly the perspective of drug court participants and those denied entry into adult drug court. These results suggest greater inclusion of drug court participants and healthcare and public health experts in the design and implementation of drug court evaluation would strengthen the quality of monitoring. Given the overdose epidemic, data collection on overdose and mortality are urgently needed before further adoption of drug courts are recommended. Future implementation and facilitation research should examine possible barriers to examining overdose and mortality within drug courts such as lack of familiarity and reluctance to include measures of adverse outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, while this study employed recommended strategies for the systematic search of the grey literature, our study may not capture all adult drug court evaluations within the grey literature, such as evaluations not indexed by Google or identified by content experts. Additionally, this study did not systematically examine peer-reviewed literature on adult drugs and results within this literature may differ. Second, this study only examined evaluations between January 2008 and July 2018 and evaluations published before or after this period may differ. Third, while we document the frequency of measures present within drug court evaluations, evaluation authors or evaluating agencies may not have included all measures of quality for which data were collected. The NDCI should establish public reporting of all evaluation data as a best practice for drug court evaluation. Fourth, we examined substance use treatment quality measures for professional addiction treatment settings recommended by organizations like American Society of Addiction Medicine. Quality measures for mutual help groups may differ from our results.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the promotion of drug courts in response to the ongoing drug overdose epidemic and calls for improving drug court evaluation, there exist limited data within the grey literature on adult drug court substance treatment services and outcomes. The limited data call into question the ability of drug courts to prevent harmful substance use related outcomes. Evaluations incorporating the perspective of people with substance use disorders and data on drug overdose death are urgently needed to ensure the health of people in these court programs.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Systematically reviewed the adult drug court evaluations within the grey literature Less than 10% reported measures related to service utilization, overdose, and mortality More than 75% contained criminal justice measures

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the numerous topic experts (state drug court representatives and academic experts who provided additional evaluations including Monica Kagey MBA LSW, Fred L. Cheesman II PhD, Elizabeth M. Nichols, Nick Leftwich MSCJ MLS, Andrea Finlay PhD, and Eileen M Ahlin PhD.

FUNDING

In the past 36 months, Dr. Joudrey received research support through Yale University from the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations through the National Clinician Scholars Program and by Clinical and Translational Science Award grant number TL1 TR001864 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science and grant number 5K12DA033312 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, each components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

In the past 36 months, Dr. Howell received research support through Yale University from the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations through the National Clinician Scholars Program and by Clinical and Translational Science Award grant number TL1 TR001864 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science and grant number 5K12DA033312 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, each components of the NIH.

In the past 36 months, Dr. Ross received research support through Yale University from Medtronic, Inc. and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop methods for postmarket surveillance of medical devices (U01FD004585), from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting (HHSM-500-2013-13018I), and from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association to better understand medical technology evaluation; Dr. Ross currently receives research support through Yale University from Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Food and Drug Administration to establish Yale-Mayo Clinic Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) program (U01FD005938), from the Medical Device Innovation Consortium as part of the National Evaluation System for Health Technology (NEST), from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS022882), from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01HS025164, R01HL144644), and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation to establish the Good Pharma Scorecard at Bioethics International and to establish the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency (CRIT) at Yale.

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE

The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH or the Department of Veterans Affairs. The above funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

ABBREVIATIONS

- MOUD

medication for opioid use disorder

- EPPI

Center Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordination Center

- SAMHSA

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- NDCI

National Drug Court Institute

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTERESTS

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Carey SM, Sanders MB, & Malsch AM (2012). Colorado StatewideDWI and Drug Court Process Assessment and Outcome Evaluation. NPC Research. https://npcresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/CO_Statewide_Process_Assessment_and_Outcome_Evaluation_09122.pdf

- Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, Booth A, Harden A, Hannes K, Thomas J, Flemming K, Garside R, & Noyes J (2018). Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 4: Methods for assessing evidence on intervention implementation. 1878–5921 (Electronic). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (1996). Treatment Drug Courts: Integrating Substance Abuse Treatment With Legal Case Processing. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US; ). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64447/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M, Hosking J, Hunter C, Lewis S, & Soffe C (2016). Summit County Drug Court Program Evaluation. BYU Marriott School of Management. https://summitcounty.org/DocumentCenter/View/3306/Drug-Court-Evaluation?bidId=

- Christie GC, Baker CGC, Cooper GR, Kennedy CPJ, Madras B, & Bondi FAGP (2017). THE PRESIDENT’S COMMISSION ON COMBATING DRUG ADDICTION AND THE OPIOID CRISIS.

- Csete Joanna, & Tomasini-Joshi D. (2015). Drug Courts: Equivocal Evidence on a Popular Intervention. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/drug-courts-equivocal-evidence-popular-intervention

- Csete Joanne, & Wolfe D. (2017). Seeing through the public health smoke-screen in drug policy. International Journal of Drug Policy, 43, 91–95. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand L (2002). Drug Courts: Better DOJ Data Collection and Evaluation Efforts Needed to Measure Impact of Drug Court Programs. US General Accounting Office. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand L (2005). Adult Drug Courts Evidence Indicates Recidivism Reductions and Mixed Results for Other Outcomes. United States Government Accountablity Office. [Google Scholar]

- Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, & Leatherdale ST (2015). Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin C, & Kushner J. (Eds.). (2008). Quality Improvement for Drug Courts: Evidence-Based Practices. National Drug Court Institute. https://www.ndci.org/resources/quality-improvement-drug-courts/

- Heck C (2006). Local drug court research: Navigating performance measures and process evaluations. National Drug Court Institute.

- Kearley BW, Cosgrove JA, Wimberly AS, & Gottfredson DC (2019). The impact of drug court participation on mortality: 15-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 105, 12–18. 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk N, Picher CE, Feder KA, & Saloner B (2017). Only One In Twenty Justice-Referred Adults In Specialty Treatment For Opioid Use Receive Methadone Or Buprenorphine. Health Affairs, 36(12), 2046–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEAD National Support Bureau. (2017). Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion Model Policy. LEAD National Support Bureau. https://www.leadbureau.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Mahood Q, Van Eerd D, & Irvin E (2014). Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(3), 221–234. 10.1002/jrsm.1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe D, & Hardin C (2016). Painting the Current Picture: A National Report on Drug Courts and Other Problem-Solving Courts in the United States, National Drug Court Institute. National Drug Court Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Matusow H, Dickman SL, Rich JD, Fong C, Dumont DM, Hardin C, Marlowe D, & Rosenblum A (2013). Medication assisted treatment in US drug courts: Results from a nationwide survey of availability, barriers and attitudes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(5), 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer D (2011). Studies Show Courts Reduce Recidivism, but DOJ Could Enhance Future Performance Measure Revision Efforts (Adult Drug Courts). [Google Scholar]

- Merlowe D, Wakeman S, Rich J, & Baston P (2016). Increasing Access to Medication-assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Drug Courts and Correctional Facilities and Working Effectively With Family Courts and Child Protective Services. American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Brekke E, Tapia F, Carver J, Cooper C, Mahoney B, & Roberts M (1997). Defining Drug Courts: The Key Components. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs: Washington, DC, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell O, Wilson DB, Eggers A, & MacKenzie DL (2012). Assessing the effectiveness of drug courts on recidivism: A meta-analytic review of traditional and non-traditional drug courts. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(1), 60–71. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mollman M, & Mehta C (2017). Neither Justice Nor Treatment. Physicians for Human Rights. https://phr.org/our-work/resources/niether-justice-nor-treatment/ [Google Scholar]

- NADCP. (2018, March 23). Historic Funding for Treatment Courts. NADCP.Org. https://www.nadcp.org/press/historic-funding-for-treatment-courts/ [Google Scholar]

- Office of Justice Programs. (2020). Drug Courts. US Department of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/238527.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Owens R (2014). FELONY DRUG COURTS EVALUATION REPORT. Idaho Administrative Office of the Courts. https://isc.idaho.gov/psc/reports/Id_Felony_DC_Eval_Report_2014.pdf

- Porterfield DS, Hinnant LW, Kane H, Horne J, McAleer K, & Roussel A (2012). Linkages between clinical practices and community organizations for prevention: A literature review and environmental scan. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(6), S163–S171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins C, Officer K, Einspruch EL, Jarvis KL, Waller MS, Mackin JR, & Carey SM (2015). Randomized Controlled Trial of Measure 57 Intensive Drug Court for Medium-to High-Risk Property Offenders: Process, Interviews, Costs, and Outcomes.

- Rubio DM, Cheesman F, & Federspiel W (2008). Performance measurement of drug courts: The state of the art. National Center for State Courts. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco LN (2018). Federal Support for Drug Courts: In Brief. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44467.pdf

- Schleifer R, Ramirez T, Ward E, & Williams C (2018). Drug Courts in the Americas. Social Science Research Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ssrccdn1/crmuploads/new_publication_3/DSD_Drug+Courts_English_online+final.pdf

- Shaffer DK (2011). Looking Inside the Black Box of Drug Courts: A Meta-Analytic Review. Justice Quarterly, 28(3), 493–521. 10.1080/07418825.2010.525222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J, Kavanagh J, Picot J, Cooper K, Harden A, Barnett-Page E, Jones J, Clegg A, Hartwell D, & Frampton GK (2010). The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of behavioural interventions for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in young people aged 13–19: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment, 14(7), 1–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner P, & Sawyer W (2019). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2019.html

- White Bird Clinic. (2020, September 29). What is CAHOOTS? White Bird Clinic. https://whitebirdclinic.org/what-is-cahoots/ [Google Scholar]

- White MT, & Kunkel TL (2017). Michigan’s Adult Drug CourtsRecidivism Analysis. National Center for State Courts. https://courts.michigan.gov/Administration/admin/op/problem-solving-courts/Documents/NCSC-Adult-RecidivismAnalysis.pdf#search=%22drug%20court%22

- Zielinski MJ, Allison MK, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Curran G, Zaller ND, & Kirchner JAE (2020). Making change happen in criminal justice settings: Leveraging implementation science to improve mental health care. Health & Justice, 8(1), 21. 10.1186/s40352-020-00122-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig JM, Rossman SB, Roman JK, Markman JA, Lagerson E, Schafer C, Institute, T. U., & America, U. S. of. (2011). The Multi-Site Adult Drug Court Evaluation: What’s Happening with Drug Courts? A Portrait of Adult Drug Courts in 2004, Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.