Abstract

Background:

Data objectively evaluating acute post-transoral robotic surgery (TORS) swallow function are limited. Our goal was to characterize and identify clinical variables that may impact swallow function components 3 weeks post-TORS.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study. Pre/postoperative use of the Modified Barium Swallow Impairment Profile (MBSImP) and Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) was completed on 125 of 139 TORS patients (2016–2019) with human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST) scores were retrospectively calculated. Uni/multivariate analysis was performed.

Results:

Dysfunctional pre-TORS DIGEST scores were predictive of post-TORS dysphagia (p = 0.015). Pre-TORS MBSImP deficits in pharyngeal stripping wave, swallow initiation, and clearing pharyngeal residue correlated with airway invasion post-TORS based on PAS scores (p = 0.012, 0.027, 0.048, respectively). Multivariate analysis of DIGEST safety scores declined with older age (p = 0.044). Odds ratios (ORs) for objective swallow function components after TORS were better for unknown primary and tonsil primaries compared to base of tongue (BOT) (OR 0.35–0.91).

Conclusions:

Preoperative impairments in specific MBSImP components, older patients, and BOT primaries may predict more extensive recovery in swallow function after TORS.

Keywords: dysphagia, HPV, Modified Barium Swallow, oropharyngeal cancer, TORS

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The long-term negative effects on swallowing, taste, saliva, and overall quality of life (QoL) after treatment with chemoradiation therapy (CRT) for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) have fueled de-escalation efforts in radiation volume and intensity.1,2 With the increased application of transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for treating OPSCC, favorable oncologic and functional outcomes post-TORS have been reported.3,4 While patient-reported outcomes after TORS have been studied, a paucity of literature exists regarding early postoperative physiological swallow function and course of recovery following TORS.5,6

Two published studies report objective findings based on videofluoroscopy that found deficits post-TORS. One prospective study incorporated the Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST) scores obtained from a Modified Barium Swallow (MBS) in 10 patients. DIGEST is a validated method to grade pharyngeal phase dysphagia based on safety (using the Penetration-Aspiration Scale [PAS]) and efficiency (using estimation of the percentage of pharyngeal residue) of bolus clearance.7,8 This study incorporated use of the MBS Impairment Profile (MBSImP), identifying mild dysphagia secondary to inefficient bolus clearance due to impaired tongue base retraction and pharyngeal contraction.8 Unfortunately, there was no pre-TORS assessment to predict post-TORS swallowing outcome. A second study collected DIGEST scores preoperatively as well as 3 weeks post-TORS on 49 patients. This study noted T stage and primary tumor volume as pre-TORS predictors of moderate to severe dysphagia (based on a summary DIGEST score ≥2).9 Interestingly, neither study noted acute objective physiologic differences associated with tumor site (tonsil vs. base of tongue [BOT]).

The goal of this study was to characterize the early functional swallow deficits after TORS by comparing preoperative and postoperative MBSImP components of swallow physiology using validated swallowing assessments. Secondary goals included identifying factors (i.e., age, T stage) that influence swallow outcomes as well as evaluating the differences in swallowing function by oropharyngeal subsite, including TORS approach for p16-positive unknown primary. A tertiary goal was to assess the utility of fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) on early swallow outcomes after TORS.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

This was a single-site, retrospective cohort study. Demographic data and clinical information were collected by retrospective chart review.

2.2 |. Participants

After approval from Emory University’s Institutional Review Board, 139 eligible participants were identified from a cohort of patients who had been treated with TORS for OPSCC and received swallowing evaluations and intervention from January 2016 to April 2019 at Winship Cancer Institute and the Department of Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery. All participants had an ipsilateral neck dissection and TORS for clinical T1 or T2 primary (tonsil, BOT, or unknown primary) for human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated squamous cell cancer. Clinical and pathologic data were updated as needed to reflect the current staging of OPSCC based on 8th edition of AJCC TNM Cancer Staging Manual. Five patients were excluded for pT3 (n = 4) or pT4 (n = 1) disease. Seven additional patients were excluded as they did not have both preoperative and postoperative swallow data, leaving 125 patients identified for study inclusion.

2.3 |. TORS procedure

TORS tonsillectomy patients underwent a radical oropharyngectomy that included resection of the tonsil, pharyngeal constrictor muscle, soft palate just lateral to the uvula, and a portion of the stylopharyngeus with variable portions of the lingual tonsil. BOT resections included the styloglossus, intrinsic musculature deep to the lingual tonsil (at variable depths dependent on tumor depth), and mucosa lining the epiglottis. Our standard workup for unknown primary included computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, physical exam, and flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy with narrow-band imaging.10 The TORS unknown primary algorithm begins with a palatine tonsillectomy (which included a portion of the palatoglossus and palatopharyngeus) ipsilateral to the p16+ nodal metastasis. If no carcinoma was noted on frozen section, we proceeded with an ipsilateral lingual tonsillectomy (incorporating 2–3 mm of intrinsic tongue muscle). If no primary was discovered in the ipsilateral lingual tonsil at frozen evaluation, a contralateral lingual tonsillectomy was performed that excludes the intrinsic tongue musculature. If a tonsil primary was identified at the time of TORS, the constrictor (without the styloglossus and stylopharyngeus) is resected and mucosal margins are revised only if necessary. If a BOT primary was identified during unknown primary approach, margins are revised only if <3 mm. One hundred and twenty-two patients had a Dobhoff tube (DHT) placed at the time of TORS.

2.4 |. Swallow studies

Pre and postoperative MBS with use of the MBSImP was completed on 125 eligible patients.11–13 Patients participated in a FEES between postoperative days 3–5. Patients that did not have post-TORS FEES evaluation were discharged on postoperative day 2 when a head and neck trained speech-language pathologist (SLP) evaluation was unavailable. Postoperative MBS was completed at 3 weeks following surgery per the TORS protocol at our facility. DIGEST scores were retrospectively calculated by chart review by a head and neck trained SLP.7 Univariate analysis was performed, stratified by clinical presentation of the primary site. Multivariate analysis was performed to validate significant correlations.

2.5 |. Swallow outcomes

Data from patients’ baseline and 3-week postoperative MBS were collected using the MBSImP. Data points included the Rosenbek 8-Point PAS, Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) scores, and Performance Status Scale – Head & Neck (PSS-HN) scores were assigned at the baseline MBS and 3-week postoperative MBS. These data points were collected by MBSImP certified, head and neck trained SLPs. The MBSImP is a validated, standardized measurement tool that rates the physiological components of the oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal phases of the swallow on an ordinal scale.10 Preoperative and 3-week postoperative MBS were analyzed using the MBSImP rating scales immediately following the study by the head and neck trained SLP. Ratings were documented in the medical record, with each component assigned a score corresponding to the worst performance on a given trial from all test boluses.10 Each MBSImP component was stratified into two groups: (1) normal to mild impairment (score 0–1) and (2) moderate to severe impairment (score 2–4) for the purpose of statistical analysis.

The PAS is a validated scale measuring the degree to which the bolus enters the airway and the patient’s response to the penetration or aspiration event.14 A PAS score of 1 indicates that material does not enter the airway, scores 2–5 represent laryngeal penetration to varying degrees, and scores 6–8 represent aspiration to varying degrees. The FOIS is designed to rate an individual’s current oral intake, from no oral intake (score = 1, tube feed dependent) to total oral intake without restrictions (score = 7).11 A FOIS score was assigned to each patient following an objective swallowing assessment based on the patient’s recommended diet level. The Normalcy of Diet subscale of the PSS-HN was also used to quantify diet level.12

Videofluoroscopy-based DIGEST scores were retrospectively assigned. DIGEST grades align with the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events framework (grade 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; and 4, life threatening).7 DIGEST scores were calculated on chart review by a head and neck trained SLP. DIGEST was dichotomized to within functional limits (WFL) or moderate–severe dysphagia (based on scores grade 2 or higher) per published data suggesting this is a meaningful split that correlates with diet level.8

2.6 |. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and medical information gathered from the chart review. The MBSImP, PAS, FOIS, and PSS-HN were scored according to each measure’s scoring protocol. Categorical patient characteristics were compared across dichotomous PAS and DIGEST scores using chisquare tests or Fisher’s exact tests, where appropriate, while continuous characteristics were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05 level, and statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Patient characteristics

Table 1 highlights patient characteristics with respect to patient demographics, pathologic stage, and pathologic variables for 125 TORS patients treated and evaluated (mean age at the time of TORS 58.7; 91% male; 93.6% Stage 1 8th ed. AJCC). Of the 125 total patients included, 56 (48%) had tonsil primaries (which captured the glossotonsillar sulcus tumors), 40 (38%) BOT primaries, and 29 (14%) unknown primaries.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics: clinical and pathologic variables for 125 consecutive TORS patients treated and evaluated

| Variable | Level | N = 125 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 13 (10.4) |

| Male | 112 (89.6) | |

| Race | African American | 17 (13.6) |

| White | 108 (86.4) | |

| Clinical presentation | Unknown primary | 29 (23.2) |

| Tonsil | 56 (44.8) | |

| BOT | 40 (32.0) | |

| T stage – 8th edition | T0 | 5 (4.0) |

| T1 | 61 (48.8) | |

| T2 | 59 (47.2) | |

| N stage – 8th edition | N0 | 14 (11.2) |

| N1 | 103 (82.4) | |

| N2 | 8 (6.4) | |

| Margin status | Unknown | 5 (4.0) |

| Negative | 117 (93.6) | |

| Positive | 3 (2.4) | |

| PNI | Yes | 18 (15.0) |

| No | 102 (85.0) | |

| LVI | Yes | 41 (34.2) |

| No | 79 (65.8) | |

| ENE | Yes | 47 (42.3) |

| No | 64 (57.7) | |

| Age at surgery | Mean | 58.43 |

| Median | 58 | |

| Minimum | 38 | |

| Maximum | 81 | |

| SD | 8.97 |

Abbreviations: BOT, base of tongue; ENE, extranodal extension; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; PNI, perineural invasion; TORS, transoral robotic surgery.

Of the 29 unknown primary cases 24 (82%) were identified; 7 in the tonsil and 17 within the BOT. Eleven unknown primary tumors were identified at the time of TORS endoscopy on frozen section and underwent complete resection, then classified as either tonsil or BOT. Tumor size ranged from 3 to 22 mm (22 T1, 2 T2). Two patients with BOT primaries underwent ipsilateral tonsillectomy at the time of TORS unknown primary protocol, and seven had childhood tonsillectomies. The remaining patients had healed from bilateral palatine tonsillectomy performed by the referring provider prior to TORS lingual tonsillectomy.

3.2 |. Swallowing physiology pre- and post-TORS

3.2.1 |. Pre-TORS

Baseline preoperative swallowing function assessments are detailed in Table 2. Pre-TORS FOIS scores indicated an exclusively oral diet (score > 5) for 100% (n = 125) of patients. PSS-HN scores indicated 95.1% (n = 117) had no baseline diet restrictions (Table S2, Supporting Information). MBSImP component scores were stratified into two groups: (1) normal to mild impairment (score 0–1) and (2) moderate to severe impairment (score 2–4), for the purpose of statistical analysis. PAS scores were stratified into two groups: (1) scores of 1–2 indicating airway protection WFL and (2) scores 3–8, indicating varying degrees of airway invasion. Pre-TORS PAS scores were WFL (score 1–2) for 96% (n = 120), with two patients demonstrating aspiration on thin liquids. Pre-TORS summary DIGEST baseline scores were 0–1 for 80.0% (n = 100) of patients (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Pre-TORS swallow function: PAS evaluation and DIGEST score by tumor site and age

| Preoperative PAS | Preoperative DIGEST summary | Preoperative DIGEST efficiency | Preoperative DIGEST safety | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Statistics | Level | WFL (1–2) N = 120 |

Pen/Asp (3–8) N = 5 |

p-valuea | 0–1 N = 100 |

2–4 N = 25 |

p-valuea | 0–1 N = 101 |

2–4 N = 24 |

p-valuea | 0–1 N = 122 |

2–4 N = 3 |

p-valuea |

| Clinical | N (Row %) | Unknown primary | 26 (89.66) | 3(10.34) | 0.151 | 23 (79.31) | 6 (20.69) | 0.107 | 23 (79.31) | 6 (20.69) | 0.059 | 28 (96.55) | 1 (3.45) | 1.000 |

| presentation of primary | N (Row %) | Tonsil | 55 (98.21) | 1 (1.79) | 49 (87.5) | 7 (12.5) | 50 (89.29) | 6 (10.71) | 55 (98.21) | 1(1.79) | ||||

| N (Row %) | BOT | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | 28 (70) | 12 (30) | 28 (70) | 12 (30) | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | |||||

| Clinical | N (Row %) | Tonsil | 55 (98.21) | 1 (1.79) | 1.000 | 49 (87.5) | 7 (12.5) | 0.034 | 50 (89.29) | 6 (10.71) | 0.017 | 55 (98.21) | 1 (1.79) | 1.000 |

| presentation of primary (excluding unknown primary) | N (Row %) | BOT | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | 28 (70) | 12 (30) | 28 (70) | 12 (30) | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | ||||

| Pathologic tumor location | N (Row %) | Unknown primary | 4(80) | 1(20) | 0.122 | 3(60) | 2(40) | 0.107 | 3 (60) | 2(40) | 0.047 | 5(100) | 0(0) | 0.660 |

| N (Row %) | Tonsil | 60 (98.36) | 1 (1.64) | 53 (86.89) | 8(13.11) | 54 (88.52) | 7(11.48) | 60 (98.36) | 1(1.64) | |||||

| N (Row %) | BOT | 56 (94.92) | 3 (5.08) | 44 (74.58) | 15 (25.42) | 44 (74.58) | 15 (25.42) | 57 (96.61) | 2(3.39) | |||||

| Age at surgery | N | 120 | 5 | 0.076 | 100 | 25 | 0.057 | 101 | 24 | 0.028 | 122 | 3 | 0.340 | |

| Mean | 58.14 | 65.4 | 57.67 | 61.48 | 57.57 | 62.04 | 58.31 | 63.33 | ||||||

| Median | 57.5 | 70 | 57 | 60 | 57 | 61 | 58 | 70 | ||||||

Note: The significant p-values are marked in bold. Abbreviations: BOT, base of tongue; DIGEST, Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity; PAS, Penetration-Aspiration Scale; TORS, transoral robotic surgery.

The p-value is calculated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) for numerical covariates; chi-square test or Fisher's exact for categorical covariates, where appropriate.

3.2.2 |. Post-TORS

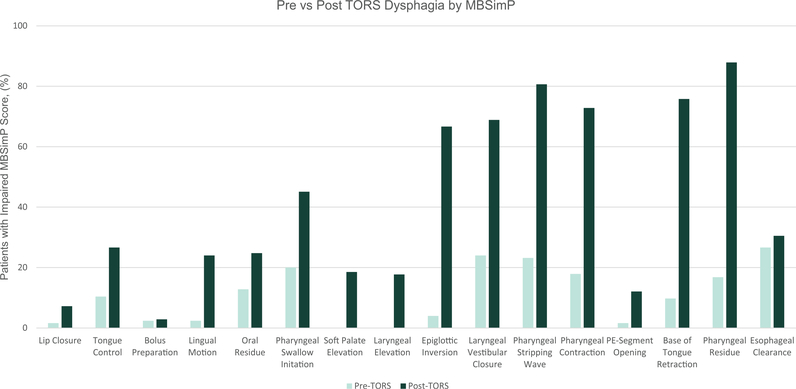

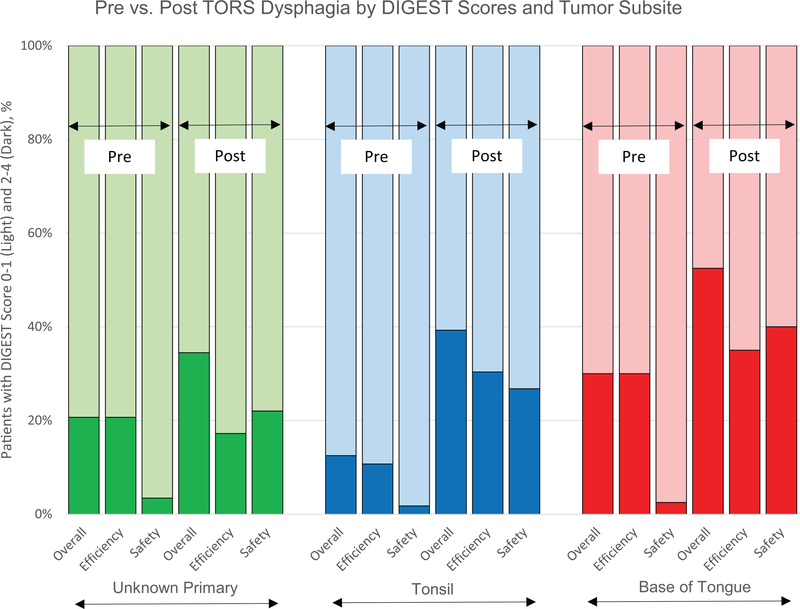

Three weeks post-TORS DIGEST scores derived from MBSImP residue component as well as PAS ratings, including information regarding volume and frequency of airway invasion, were altered from baseline (Figures 1 and 2 and Table S1). Seventy-two (57.6%) patients demonstrated summary DIGEST scores of 0–1 versus 53 (42.4%) with scores of 2–4, consistent with moderate to severe dysphagia. Post-TORS DIGEST scores were further discriminated into safety and efficiency scores (Table S1). Eighty-eight (70.4%) patients achieved DIGEST safety scores of 0–1.

FIGURE 1.

Pre- versus post-transoral robotic surgery (TORS) dysphagia by Modified Barium Swallow Impairment Profile (MBSImP)—percent of patients with moderate to severe (2–4) MBSImP score for each individual MBSImP component. Using McNemar’s test for paired proportions, all components except for bolus preparation and esophageal clearance had a significantly more impaired MBSImP score in the post-TORS period. See Table S4 for details

FIGURE 2.

Pre- versus post-transoral robotic surgery (TORS) dysphagia by Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST) score and tumor subsite. Percent of patients with normal or mild (0–1) DIGEST scores and moderate to life-threatening (2–4), stratified by tumor subsite. DIGEST score is further stratified into overall, efficiency, and safety scores

PAS scores (3–8) consistent with penetration and/or aspiration at 3-week post-TORS were identified in 77 patients (61.6%), 46 of which aspirated, and 26 of those were silent as determined by MBS. Of the 46 patients that aspirated, 43 (91.3%) aspirated thin liquids and eight patients (17.4%) aspirated multiple consistencies. Thirty-six (78.2%) of the patients that aspirated were noted to do so after the swallow secondary to pharyngeal residue.

3.3 |. Factors predicting post-TORS dysphagia

Preoperative MBSImP scores are reported as a function of post-TORS PAS (Table S1). Moderate to severe impairments in swallow initiation and in clearing pharyngeal residue at preoperative MBSImP correlated with penetration and aspiration at 3-week post-TORS (score 3–8, p = 0.034, p = 0.046). At 3-week post-TORS, MBSImP components (initiation, epiglottic inversion, laryngeal vestibular closure, pharyngeal stripping wave, pharyngeal contraction, pharyngoesophageal segment distention, BOT retraction, pharyngeal residue) correlated with severe PAS deficits (p < 0.031–0.001). Dysfunctional pre-TORS DIGEST scores (≥2) were predictive of post-TORS dysphagia based on summary DIGEST score 3 weeks after TORS (p = 0.015) (Table S1). Sixty-seven percent of patients demonstrating MBSImP pre-TORS pharyngeal residue deficits had moderate to severe dysphagia according to 3 weeks post-TORS summary DIGEST scores (p = 0.014) (Table S1). Post-TORS impairment (moderate to severe) in 8 of 16 MBSImP components (lip closure, laryngeal elevation, epiglottic inversion, laryngeal vestibule closure, pharyngeal stripping wave, pharyngeal contraction, pharyngoesophageal segment distention, BOT retraction) significantly correlated with dysphagia based on summary DIGEST scores 3 weeks after TORS (p < 0.005–0.001) (Table S1). Only “preoperative impairment in pharyngeal stripping” wave on MBSImP correlated with concerning DIGEST safety scores 2–4 post-TORS (p = 0.04). At 3 weeks, moderate to severe deficiencies on post-TORS MBSImP correlated with worse DIGEST safety scores in 8 of 16 components (lip closure, laryngeal elevation, epiglottic inversion, laryngeal vestibular closure, pharyngeal stripping wave, pharyngeal contraction, pharyngoesophageal segment distention, BOT retraction) (p < 0.019) (Table S1). No pre-TORS MBSImP components correlated with impaired DIGEST efficiency scores at 3 weeks post-TORS. At 3 weeks, moderate to severe deficiencies on post-TORS MBSImP correlated with worse DIGEST efficiency scores in 9 of 16 components (with overlap in seven MBSImP components from those on DIGEST safety scores) (p < 0.017–0.001) (lip closure, lingual motion, oral residue, laryngeal elevation, epiglottic inversion, laryngeal vestibular closure, pharyngeal stripping wave, pharyngoesophageal segment distention, and BOT retraction) (Table S1).

Controlling for age, multivariate analysis identified odds ratios (OR) correlating with improved scores for clinical unknown primaries (n = 29) treated with the TORS unknown primary approach without reaching significant p-value across all objective swallow assessments (OR 0.34–0.42). Age, set as a continuous variable, was identified as a significant factor in DIGEST safety scores (p = 0.044). Patients with tonsil primaries were significantly less likely to have poor DIGEST efficiency scores (p = 0.046) (Table S3a,b).

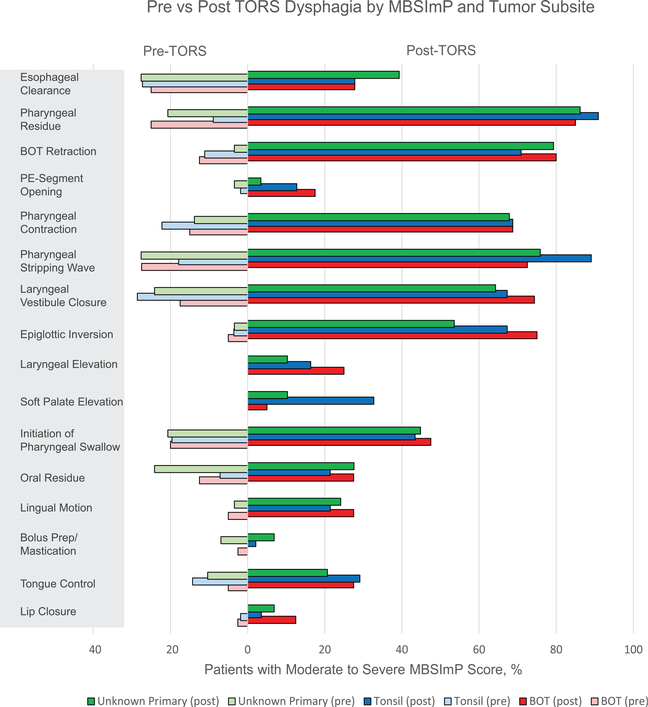

3.4 |. Differences in swallow function by tumor site

PAS scores post-TORS did not demonstrate a significant difference by site of primary (tonsil vs. BOT, p = 0.123) (Figure 3). Moderate to severe pharyngeal residue at the time of pre-TORS MBSImP were observed in 25% of BOT primaries (p = 0.033) compared to 9% of tonsil primaries. On post-TORS evaluation, MBSImP soft palate deficiencies and pharyngeal stripping wave deficits were associated with tonsil primaries when compared to BOT primaries (p < 0.001 and p = 0.037, respectively) (Figure 4). Pre-TORS summary DIGEST scores of 0–1 were recorded with increased frequency by patients with tonsil primaries (87.5%) compared to BOT primaries (70.0%) (p = 0.034). Preoperative DIGEST efficiency scores of 0–1 also correlated with primary site (tonsil 89.2% vs. BOT 70.0%, p = 0.017) and age at the time of surgery (p = 0.028). No significant differences in summary DIGEST scores were observed by primary site at 3-week post-TORS. Additionally, no differences were observed by T stage within a site (i.e., T1 BOT vs. T2 BOT) or across sites (i.e., T1 tonsil/BOT vs. T2 tonsil/ BOT) at 3-week post-TORS. Digest safety scores did not reach significant difference based on site. When comparing the difference in DIGEST efficiency scores post-TORS between tonsil primaries and BOT primaries, no significant differences were observed.

FIGURE 3.

Pre- versus post-transoral robotic surgery (TORS) dysphagia by Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) score and tumor subsite. At 3 weeks, Modified Barium Swallow Impairment Profile (MBSImP) components (initiation, epiglottic inversion, laryngeal vestibular closure, pharyngeal stripping wave, pharyngeal contraction, pharyngoesophageal segment distention, base of tongue (BOT) retraction, pharyngeal residue) correlated with severe PAS deficits (p < 0.031–0.001). PAS scores post-TORS did not demonstrate a significant difference by site of primary (p = 0.123)

FIGURE 4.

Pre- versus post-transoral robotic surgery (TORS) dysphagia by Modified Barium Swallow Impairment Profile (MBSImP) according to clinical site at presentation. Moderate to severe pharyngeal residue at the time of pre-TORS MBSImP was observed more often in 25% of base of tongue (BOT) primaries (p = 0.033) compared to 9% of tonsil primaries. On post-TORS evaluation, MBSImP soft palate deficiencies and pharyngeal stripping wave deficits were associated with tonsil primaries when compared to BOT primaries (p < 0.001 and p = 0.037, respectively)

3.5 |. FEES functional assessment

Eighty-two of 125 patients (65.6%) had FEES assessment between POD#3–5 (Table 3). Patients that did not have post-TORS FEES evaluation were discharged on postoperative day 2 when a head and neck trained SLP evaluation was unavailable. Forty (48.8%) of the 82 patients demonstrated aspiration on FEES, 19 of which were silent events. Seventy of the 82 patients (86.4%) that underwent FEES required continued use of the DHT.

TABLE 3.

Postoperative day 3–5 swallowing parameters: early FEES evaluation 3–5 days post-TORS with FOIS and PSS-HN assessments for 82 patients

| Variable | Level | N = 82 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 3–5 day FEES PAS | 1 | 7 (8.9) |

| 2 | 4 (5.1) | |

| 3 | 11 (13.9) | |

| 4 | 5 (6.3) | |

| 5 | 12 (15.2) | |

| 6 | 7 (8.9) | |

| 7 | 14 (17.7) | |

| 8 | 19 (24.1) | |

| Missing | 3 | |

| Continue tube feeds | Yes | 70 (86.4) |

| No | 11 (13.6) | |

| Missing | 1 | |

| 3–5 day diet recommendation | NPO | 1 (1.2) |

| Soft | 3 (3.7) | |

| Puree | 5 (6.1) | |

| Full liquids | 17 (20.7) | |

| Tx feeds | 56 (68.3) | |

| 3–5 day diet strategies (#) | 0 | 9 (11.0) |

| 1 | 7 (8.5) | |

| 2 | 39 (47.6) | |

| 3 | 19 (23.2) | |

| 4 | 8 (9.8) | |

| Thickened liquids (3–5 day postoperative) | Yes | 20 (25.3) |

| No | 59 (74.7) | |

| Missing | 3 | |

| 3–5 day FOIS | Tube dependent w/minimal/inconsistent intake | 44 (55.0) |

| Tube supplements with consistent oral intake | 23 (28.8) | |

| Total oral intake | 7 (8.8) | |

| Total oral intake of multiple consistencies requiring special preparation | 3 (3.8) | |

| Total oral intake with no special preparation, but must avoid specific foods or liquid items | 3 (3.8) | |

| Missing | 2 | |

| 3–5 day PSS-HN | Cold liquids | 15 (18.5) |

| Warm liquids | 49 (60.5) | |

| Pureed foods | 6 (7.4) | |

| Soft foods requiring no chewing | 8 (9.9) | |

| Soft chewable foods | 3 (3.7) | |

| Missing | 1 |

Note: PAS scores (1–2) considered within normal limits; scores (3–8) represent increasing impairment of airway protection.

Abbreviations: FEES PAS, fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing – Penetration-Aspiration Scale; FOIS, Functional Oral Intake Scale; NPO, nothing by mouth; PSS-HN, Performance Status Scale - Head and Neck.

3.6 |. Feeding tube removal

Seventeen of 79 patients (21.5%) had the DHT removed by SLP after POD#3–5 FEES, prior to discharge from the hospital. Twenty-three (28%) patients were cleared for an oral diet with tube feed supplementation at the time of discharge. Thirty-nine patients (31.2% of 125) had the DHT removed during a postoperative outpatient follow-up visit based on clinical SLP evaluation and collaboration with a dietitian (mean time to DHT removal 18.7 days [range 1–43]). Sixty-eight patients (54% of 125) had the DHT in place at the time of the postoperative MBS (median time to post-TORS MBS was 21 days [range 13–48 days]).

4 |. DISCUSSION

The increase in prevalence of HPV-associated OPSCC with trends indicating rise in age at diagnosis coupled with favorable long-term survival prognosis highlights the importance of improving QoL.15 Minimizing injury to swallow function secondary to treatment continues to drive clinical trial designs. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date detailing the predictive impact of TORS on swallow physiology within the first 3 weeks after surgery.

Through the use of MBSImP and DIGEST scores, we observed significant physiologic deficits following TORS that compromised swallowing safety and efficiency in the early postoperative period. A majority of patients were found to have impairments in six specific components of pharyngeal swallow: epiglottic inversion (66.7%), laryngeal vestibular closure (68.9%), pharyngeal stripping wave (80.6%), pharyngeal contraction (72.8%), BOT retraction (75.8%), and pharyngeal residue (87.9%). Resection of the styloglossus in both tonsil and BOT primaries may have contributed to impairment in bolus propulsion. In addition, the impairments in laryngeal elevation and driving pressure on the bolus, which could reduce epiglottic inversion as well as promote increased pharyngeal residue may be related to the resection of the superior constrictor, soft palate, and stylopharyngeus during the TORS.

In this study, we identified the importance of MBSImP evaluation pre-TORS. Pre-TORS deficits in initiation and pharyngeal residue on MBSImP correlated with post-TORS DIGEST scores consistent with moderate to severe dysphagia (p = 0.018). “Pre-operative impaired initiation of swallow as well as clearance of pharyngeal residue” also correlated with PAS scores >3, consistent with airway invasion 3 weeks after TORS (p = 0.034, p = 0.046). Due to the incidence of silent aspiration noted post-TORS, this suggests that a clinical bedside swallow evaluation without instrumental assessment will likely be inadequate in identifying aspiration in this population despite reports that aspiration may be rare.6

It is well known that aspiration places patients at risk of postoperative pneumonia. A study that queried the Nationwide Readmission Database (NRD) identified 8.5% readmission rate after TORS (n = 955) for dysphagia-related complications, and re-admitted patients were 4 times more likely to have aspiration or develop pneumonia compared to those that were not re-admitted (9.4% vs. 2.4%, p < 0.01).16 None of our patients were re-admitted for pneumonia post-TORS. We postulate our readmissions were mitigated with the use of DHT post-TORS.

MBSImP deficits in pharyngeal residue and pharyngeal stripping wave are factors to consider prior to determining treatment with primary TORS versus primary nonsurgical treatment. A third preoperative component to evaluate is the DIGEST efficiency score for clinically identified tongue base tumors. Poor DIGEST efficiency scores in the setting of BOT primaries correlated with worse outcomes compared to tonsil primaries on multivariate analysis (p = 0.046) (Table S3a). At this time, we do not have longitudinal data to make the assertion that these three factors are definitive reasons to advocate for primary nonsurgical therapy as opposed to primary surgery, but it may help educate patients on what to expect in the acute post-TORS setting. The other caveat is that we do not have a cohort of patients with pre-CRT (70 Gy IMRT + cisplatin [the current standard of care], or radiation alone in the setting of low volume disease) MBS to compare pretreatment and post-treatment MBSImP scores.17 In a similarly detailed study of objective swallow measures after (mean 4.7 months) CRT (IMRT 70 Gy, 67% received cisplatin, 89% bilateral RT), our colleagues from Johns Hopkins studied MBS components, PAS, and FOIS. Abnormal PAS scores were noted in 45% of swallow studies impacted by deficits in tongue base retraction, epiglottic tilt, hyoid elevation, pharyngeal constriction, and velopharyngeal closure on univariate analysis (p < 0.05).18 Interestingly, there was a trend toward increasing T stage and PAS deficits (p = 0.059).18 Only abnormal pretreatment swallow status was associated with abnormal PAS on multivariate analysis (p = 0.09).18 Our colleagues at M. D. Anderson studied DIGEST scores comparing TORS versus (C)RT at multiple time points to characterize and compare swallow outcomes. At baseline, 96.2% of patients undergoing CRT had DIGEST scores <2 declining to 65.4% 3–6 months after completing treatment. Comparatively, TORS patients with DIGEST scores <2 were 92% and 72% pre-TORS and 3–6 months after surgery, respectively.9

Clinically, there is the prevailing hypothesis among TORS surgeons that BOT resections have worse swallow outcomes early after TORS when compared to tonsil resections. The aforementioned study from M. D. Anderson did not identify a significant difference in early swallow function based on primary site.9 We did note significant differences on MBSImP components between tonsil and BOT primaries. For instance, tonsil primaries demonstrated significant declines in pharyngeal stripping wave and soft palate elevation, correlating with the resection of the superior constrictor muscle, branches of the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the palatopharyngeus and palatoglossus muscles (disrupting the interdigitation with the levator veli palatini), respectively. These findings highlight the complexity of swallow physiology and how the components are a part of a synchronized mechanism that may continue to function despite the lack of one component or another. Interestingly, the relatively significant differences in the various components do not translate to a distinct swallow disadvantage (based on p-values) according to DIGEST scores for tumor site. However, multivariate analysis demonstrated that tonsil primaries had lower odds of having highly disrupted swallow function after TORS in the acute setting (PAS scores >3, OR = 0.55; summary DIGEST ≥2, OR = 0.65; safety DIGEST ≥2, OR = 0.63).

We observed that DIGEST summary, safety, and efficiency scores trended better 3 weeks after TORS for unknown primary compared to BOT glossectomy on multivariate analysis [OR 0.34–0.42]. Of the unknown primaries 18 of the 29 (62%) underwent bilateral lingual tonsillectomy. While this did not reach significance, it is plausible our result could be indirectly associated with tumor stage, given that unknown primary tumors are often small. Initial swallowing function has been shown to negatively correlate with tumor stage though our series did not have similar findings.8 At our institution, T1 and T2 tonsils tend to result in the same defect after oropharyngectomy, while T1 BOT tumors may potentially have smaller resections. This translates to consistent defects despite primary tumor size for tonsil cancers. Variations in swallow likely correlate with native tissue volume loss.8

We attempted to compensate for the inefficiency and safety concerns with temporary DHT placement to supplement nutritional goals and support healing postoperatively. Prior studies have shown varying opinions on the presence of DHT placement during the swallow.19,20 One study in older healthy adults did find that patients had a higher incidence of airway invasion, pharyngeal residue, and pharyngeal transit times.20 We acknowledge that the presence of a DHT may impact swallow recovery secondary to the irritation and pain, along with the unknown effects related to driving pressure and pharyngeal clearance. We evaluated swallow function for 68 patients at 3-week MBS with a DHT in place and noted that there was correlation with aspiration in patients with DHT compared to those without DHT at 3-week MBS (n = 56) (p < 0.001). Confounding this finding is that our patients follow-up at 2 weeks post-TORS to discuss pathology, to receive recommendations for adjuvant therapy, and to assess function and caloric intake with a SLP and dietitian. If the dietitian is confident that the patient is able to meet caloric goals the DHT is removed at 2 weeks. This was performed for 71% (39 of 56) of patients that did not have a DHT at the time of MBS and may contribute to selection bias with respect to improved PAS scores. No other components within the MBSImP or DIGEST demonstrated a significant difference based on the presence of DHT at 3-week swallow evaluation. While continuing use of a DHT for up to 3 weeks postoperatively can be considered long compared to other institutions, we started with a conservative approach to initiating oral feeding with patients undergoing TORS. DHT were kept in place to ensure adequate nutrition and hydration in the setting of compromised safety and efficiency. However, our institution is moving toward earlier DHT removal at the 10 day postoperative follow-up visit with the surgeon and SLP. This transition to earlier DHT removal allows adequate nutrition and hydration to facilitate early postoperative healing and possibly also facilitate improvement in the early swallow recovery.

We assert that multidisciplinary care with baseline swallowing assessment and education by a skilled SLP followed by early instrumental swallow assessment and therapy is critical for educating patients regarding anticipated aspects of dysphagia post-TORS in addition to safely and effectively maximize swallow function postoperatively. While the current literature places a focus on 1-year swallow outcomes post-TORS, we highlight early post-TORS swallow impairments and the critical role SLP recommendations for swallow assessment and intervention play in pre/postoperative multidisciplinary care.9 We noted that early FEES (POD#3–5) led to qualitative improvements in documenting swallow function, specifically with aspiration and residue, as well as guiding appropriate and targeted intervention. While these interventions did not result in significant swallow improvement compared to patients who did not participate in a FEES, we did see noticeable improvement in both the safety and efficiency of the swallow in the first 3 weeks postoperatively. We believe they may be particularly beneficial to the older TORS patients, particularly given that multivariate analysis correlated with older patients having worse DIGEST safety scores (≥2) after TORS in the acute setting (p = 0.044). FEES was additionally a beneficial tool in biofeedback, for patients who silently aspirated or were not sensate to residue.

One limitation of our study is that although MBSImP components were assigned at the initial review of the MBS, the results were not collected through a blinded review process in real time. Additionally, DIGEST scores were retrospectively collected. Although DIGEST scores were assigned by a head and neck trained SLP with experience using DIGEST, in future studies, DIGEST will be scored at the time of the MBS. While we have accumulated robust functional data, we failed to collect and incorporate QoL measures to compare the objective result to patient perception. Finally, we acknowledge the exploratory nature of all the pairwise tests within site (i.e., tonsil vs. BOT vs. unknown primary).

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

Overall, TORS for BOT and tonsil cancer results in oropharyngeal physiological swallow impairments within the first 3 weeks. Patients did not return to their baseline status during the 3 week study period. Clinical presentation with an unknown primary has a greater likelihood for improved early swallow outcomes. Patients demonstrating baseline pharyngeal stripping wave deficits/pharyngeal residue on MBSImP as well as those with BOT tumors with DIGEST efficiency deficits experienced worse swallow outcomes postoperatively. Older patients were also found to have worse outcomes. These patients should be counseled prior to TORS regarding anticipated functional dysphagia and the rehabilitative course to follow.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yom SS, Torres-Saavedra P, Caudell JJ, et al. NRG-HN002: a randomized phase II trial for patients with p16-positive, nonsmoking-associated, locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(3):684–685. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris RL, Flamand Y, Weinstein GS, et al. Transoral robotic surgical resection followed by randomization to low-or standard-dose IMRT in resectable p16+ locally advanced oropharynx cancer: a trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E3311). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein GS, O’Malley BW Jr, Magnuson JS, et al. Transoral robotic surgery: a multicenter study to assess feasibility, safety, and surgical margins. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1701–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Almeida JR, Li R, Magnuson JS, et al. Oncologic outcomes after transoral robotic surgery: a multi-institutional study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:1043–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutcheson KA, Holsinger FC, Kupferman ME, Lewin JS. Functional outcomes after TORS for oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(2): 463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albergotti WG, Jordan J, Anthony K, et al. A prospective evaluation of short-term dysphagia after transoral robotic surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Cancer. 2017;123 (16):3132–3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutcheson KA, Barrow MP, Barringer DA, et al. Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST): scale development and validation. Cancer. 2017;123(1):62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazarus CL, Ganz C, Ru M, Miles BA, Kotz T, Chai RL. Prospective instrumental evaluation of swallowing, tongue function, and QOL measures following transoral robotic surgery alone without adjuvant therapy. Head Neck. 2019;41(2):322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutcheson KA, Warneke CL, Yao CM, et al. Dysphagia after primary transoral robotic surgery with neck dissection vs nonsurgical therapy in patients with low-to intermediate-risk oropharyngeal cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019; 145(11):1053–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Mulki K, Hamilton J, Kaka AS, et al. Narrowband imaging for p16+ unknown primary squamous cell carcinoma prior to transoral robotic surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020; 163:1198–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin-Harris B, Brodsky MB, Michel Y, et al. MBS measurement tool for swallow impairment—MBSImp: establishing a standard. Dysphagia. 2008;23:392–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crary MA, Mann GC, Groher ME. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(8):1516–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Windon MJ, D’Souza G, Rettig EM, et al. Increasing prevalence of human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancers among older adults. Cancer. 2018;124(14):2993–2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parhar HS, Gausden E, Patel J, et al. Analysis of readmissions after transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2018;40(11):2416–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillison ML, Trotti AM, Harris J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab or cisplatin in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10166): 40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starmer HM, Tippett D, Webster K, et al. Swallowing outcomes in patients with oropharyngeal cancer undergoing organ-preservation treatment. Head Neck. 2014;36(10):1392–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leder SB, Suiter DM. Effect of nasogastric tubes on incidence of aspiration. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(4):648–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pryor LN, Ward EC, Cornwell PL, O’Connor SN, Finnis ME, Chapman MJ. Impact of nasograstric tubes on swallowing physiology in older, healthy subjects: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(4):572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.