Abstract

Background

Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration (CVVH) can be used to reduce fluid overload and tissue edema, but excessive fluid removal may impair tissue perfusion. Skin blood flow (SBF) alters rapidly in shock, so its measurement may be useful to help monitor tissue perfusion.

Methods

In a prospective, observational study in a 35-bed department of intensive care, all patients with shock who required fluid removal with CVVH were considered for inclusion. SBF was measured on the index finger using skin laser Doppler (Periflux 5000, Perimed, Järfälla, Sweden) for 3 min at baseline (before starting fluid removal, T0), and 1, 3 and 6 h after starting fluid removal. The same fluid removal rate was maintained throughout the study period. Patients were grouped according to absence (Group A) or presence (Group B) of altered tissue perfusion, defined as a 10% increase in blood lactate from T0 to T6 with the T6 lactate ≥ 1.5 mmol/l. Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed and areas under the curve (AUROC) calculated to identify variables predictive of altered tissue perfusion. Data are reported as medians [25th–75th percentiles].

Results

We studied 42 patients (31 septic shock, 11 cardiogenic shock); median SOFA score at inclusion was 9 [8–12]. At T0, there were no significant differences in hemodynamic variables, norepinephrine dose, lactate concentration, ScvO2 or ultrafiltration rate between groups A and B. Cardiac index and MAP did not change over time, but SBF decreased in both groups (p < 0.05) throughout the study period. The baseline SBF was lower (58[35–118] vs 119[57–178] perfusion units [PU], p = 0.03) and the decrease in SBF from T0 to T1 (ΔSBF%) higher (53[39–63] vs 21[12–24]%, p = 0.01) in group B than in group A. Baseline SBF and ΔSBF% predicted altered tissue perfusion with AUROCs of 0.83 and 0.96, respectively, with cut-offs for SBF of ≤ 57 PU (sensitivity 78%, specificity 87%) and ∆SBF% of ≥ 45% (sensitivity 92%, specificity 99%).

Conclusion

Baseline SBF and its early reduction after initiation of fluid removal using CVVH can predict worsened tissue perfusion, reflected by an increase in blood lactate levels.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13613-021-00847-z.

Keywords: Peripheral perfusion, Microcirculation, Hemodialysis, Laser flowmetry, Lactate concentration

Introduction

Optimal fluid balance is an essential part of patient management. In patients with circulatory shock, fluid administration is widely used to increase cardiac output and restore tissue perfusion, but a high fluid balance can result in tissue edema and is associated with increased mortality [1–4]. When spontaneous diuresis is inadequate, fluid removal using continuous veno-venous hemodialysis (CVVH) is a valuable therapeutic option to eliminate excess fluid [4, 5]. However, aggressive fluid removal can cause hemodynamic compromise resulting in tissue hypoperfusion, and necessitating cessation of fluid removal despite the persistence of tissue edema [2, 3, 6–8]. In severe cases, hypotension may develop, leading to impaired organ function and increased mortality [9–11].

At the bedside, decreased tissue perfusion can be assessed by an abnormally elevated blood lactate concentration, although several medications, such as metformin, propofol or β2 agonists, can also influence lactate levels [12, 13]. The persistence of hyperlactatemia or an increase in lactate concentration during resuscitation reflects the severity of tissue hypoperfusion and is related to more severe organ dysfunction and higher mortality [14–17]. Hyperlactatemia usually presents when hemodynamic conditions are compromised [18–20].

Skin hypoperfusion occurs before systemic hemodynamic variables worsen [9, 21–23] and its persistence has been shown to be associated with higher mortality [24–26]. Additionally, a shortening of the prolonged capillary refill time (CRT) during resuscitation suggested resolution of tissue hypoperfusion, as reflected by a reduction in lactate concentration [25, 27–29]. Hence, monitoring changes in skin perfusion may be useful to track the development or worsening of tissue hypoperfusion.

Skin laser Doppler (SLD) is a simple noninvasive tool that has been widely used in clinical studies to evaluate cutaneous microcirculatory perfusion [24, 26, 30]. SLD measures local microcirculatory blood flow including perfusion in capillaries (nutritive flow), arterioles, venules and shunting vessels [31–33]. We recently showed that skin blood flow (SBF) measured on the finger using SLD was altered in circulatory shock [26].

In the present study, we evaluated changes in SBF during fluid removal with CVVH in patients with circulatory shock and determined whether changes were associated with altered tissue perfusion as reflected by an increase in blood lactate concentration.

Methods

This prospective, observational study was conducted from 1 November 2017 to 30 October 2018 in the 35-bed Department of Intensive Care of Erasme University Hospital (Brussels, Belgium). The study protocol was approved by the local ethical Committee (Protocol number P2017/013/B406201730812), and informed consent was signed by all patients or their next of kin.

Patients

All consecutive ICU patients with circulatory shock (vasopressor support needed to maintain mean arterial pressure [MAP] ≥ 65 mmHg, and at least one sign of poor tissue perfusion [altered conscious level, mottled skin, or arterial lactate ≥ 2 mmol/l] [34–36] were screened. If, during the ICU stay, these patients required fluid removal using continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF), they were considered for inclusion. Patients with any of the following were excluded: presence of any skin lesion at the site of measurement that would have made measurements difficult; a history of Raynaud's phenomenon or systemic sclerosis; receipt of metformin, propofol, β2 agonist or a blood transfusion during the study period; refusal to sign informed consent; previous inclusion in the study.

Measurements

The APACHE II score [37] was calculated using the worst data during the first 24 h following ICU admission. The sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score [38] on admission and at the time of study inclusion (start of fluid removal using CVVHDF) were recorded. The presence of signs of poor tissue perfusion [oliguria (urine output < 0.5 ml/kg/h), altered conscious level assessed using the “assumed” Glasgow Coma Scale, mottled skin, arterial lactate level ≥ 2 mmol/l] were noted at shock diagnosis and the CRT was measured (routine practice in patients with shock during the study period); the same variables were recorded at study inclusion (start of fluid removal using CVVHDF). Skin mottling was assessed using the mottling score [39] and a score ≥ 2 was considered as clinically significant. CRT was determined by applying pressure to the tip of the finger for at least 15 s until the skin showed whitening; the time until return of baseline coloration after release of the pressure was measured with a chronometer.

SBF was measured on the ventral side of the index finger at study inclusion (T0), and 1 (T1), 3 (T3), and 6 (T6) hours later. The researchers who performed the SLD measurements were different from the team managing the CVVHDF. The peripheral perfusion index (PPI) was obtained from the pulse oximeter positioned on the contralateral side to that used for SBF measurements and recorded from the bedside monitor (IntelliVue MP70 monitor, Philips Medical Systems, Boblingen, Germany) at the same timepoints.

Hemodynamic variables, norepinephrine dose and blood gas data, including central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) and arterial lactate concentration, were obtained at shock diagnosis and at T0, T1, T3 and T6. The use of mechanical ventilation at the time of shock diagnosis, and the duration of CVVHDF and the cumulative fluid balance from the onset of circulatory shock until study inclusion were recorded. The use of sedative agents during the 24 h after ICU admission and at T0 was noted. If the norepinephrine dose was increased during the study period, the time from T0 to the first increase in norepinephrine dose was noted; the MAP just before the first increase in norepinephrine dose was also recorded.

SBF measurements

SBF was evaluated using a SLD device (PeriFlux System 5000, Perimed, Jarfalla, Sweden) with a small thermostatic SLD probe (Reference number 457, Perimed). This probe enables one to simultaneously measure and alter the temperature at the place where it is positioned. The probe is attached to the skin with a double-sided tape provided with the monitor. The laser beam emitted by the SLD machine has a wavelength of 780 nm, which allows an evaluation depth between 0.5 and 1.0 mm below the skin surface. The back-scattered light is collected by the probe and the change in light wavelength is proportional to the red blood cell (RBC) velocity in the studied area, thus providing a noninvasive measurement of SBF expressed as perfusion units (PU). Data were continuously recorded for future off-line analyses using PeriSoft software 2.5.5 (Perimed). To reduce the short-term intra-individual variation in SLD that has been reported in previous studies [40–42], the SLD probe was kept on the same area in each patient throughout the study period. The relative change in SBF (∆SBF%) during the first hour of fluid removal by CVVHDF was calculated using the formula: SBF at T0−SBF at T1/ SBF at T0 × 100. All SBF measurements were obtained in the supine position and at basal skin temperature, which was recorded prior to the measurement. During the measurements, hand movements and changes to the patient’s position were not allowed; SBF measurements were delayed at least 10 min in agitated patients.

Renal replacement therapy

All patients who underwent fluid removal by CVVHDF (Primaflex®, Baxter, Chicago, USA) with a ST100-AN69 membrane had a 14F double-lumen catheter inserted in the femoral or jugular vein. According to our local protocol, blood flow and dialysate flow were set at 2 ml/min/kg and 20 ml/h/kg, respectively. Pre-dilution and post-dilution replacement fluids were prescribed at 20 ml/h/kg and 10 ml/h/kg, respectively. Regional anticoagulation was achieved using trisodium citrate. Arterial blood gases and ionized calcium concentration were evaluated and corrected according to local protocols. The time to initiate fluid removal by CVVHDF and the rate of fluid removal were determined by the care team; the rate was kept stable during the study period.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the distribution in all variables was tested using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and data are presented as median (25th–75th percentiles) or mean (with standard deviation) as appropriate. Patients were separated into two groups according to the absence (group A) or presence (group B) of altered tissue perfusion, defined as an increase in blood lactate of ≥ 10% over 6 h (with a 6-h lactate ≥ 1.5 mmol/l). Additionally, the patients were grouped by the type of shock (septic shock vs cardiogenic shock) and the start of fluid removal by CVVHDF (fluid removal started at the same time as CVVHDF vs fluid removal started after initiation of CVVHDF). Differences between groups were assessed using a Chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, Mann–Whitney U test, ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis or Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate. Repeated ANOVA was used to evaluate the change in SBF over time between groups. We plotted the sensitivity and specificity using a receiving operating characteristics (ROC) curve, and the area under the curve (AUROC) was calculated for the different variables as a measure of their ability to predict altered tissue perfusion. AUROCs are presented as mean ± SD with 95% confidence interval and were compared using the Hanley and McNeil method. To assess possible variables correlated with the different SBF-derived variables, we plotted individual data on graphs and calculated the Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient (r2) as appropriate. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA15.0 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, Texas).

Results

Eighty-two patients with circulatory shock were screened; 53 underwent fluid removal by CVVHDF and were considered for inclusion. Eleven were excluded, because of severe agitation (n = 1), receipt of blood transfusion (n = 3), and change in ultrafiltration rate during the study period (n = 7) so that 42 were included in the study (31 with septic shock, 11 with cardiogenic shock). Fluid removal was initiated at the same time as CVVHDF in 19 patients, and a median of 3.5 (2.4–5.7) hours after CVVHDF had been started in 23 patients. Tissue perfusion was altered (as defined by an increase in blood lactate of ≥ 10% over 6 h, with a 6-h lactate ≥ 1.5 mmol/l) in 22 patients (Group B) and unaltered in 20 (Group A).

There were no differences in severity scores, MAP, cardiac index (CI), norepinephrine dose, lactate concentration, presence of oliguria, or CRT between groups A and B at the time of diagnosis of shock (Additional file 1: Table S1). Skin mottling was present in seven patients in Group B and none in Group A at shock diagnosis (Additional file 1: Table S1). The median lactate concentration in all patients was 3.0 (2.8–3.8) mmol/l (Additional file 1: Table S1).

At study inclusion, there were no significant differences between groups A and B in severity scores, MAP, CI, norepinephrine dose, lactate concentration, ScvO2, PPI, CRT, fluid removal rate, or cumulative fluid balance (Table 1) or between septic shock versus cardiogenic shock patients (Additional file 1: Table S2). Norepinephrine dose was lower in patients whose fluid removal was started at the same time as CVVHDF than in patients whose fluid removal started later (Additional file 1: Table S3). Oliguria was observed in all patients at study inclusion and hyperlactatemia in 11 patients (Table 1). No patients had skin mottling at study inclusion. Sixteen patients (38%) died in the ICU.

Table 1.

Main clinical characteristics at admission or study inclusion

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 42) | Group A (n = 20) | Group B (n = 22) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On admission | ||||

| Age (years) | 63 (53–73) | 68 (48–73) | 61 (57–71) | 0.6 |

| APACHE II score | 24 (17–26) | 22 (14–27) | 24 (17–26) | 0.8 |

| SOFA score | 12 (9–14) | 11 (8–14) | 10 (10–14) | 0.8 |

| At study inclusion | ||||

| SOFA score | 9 (8–12) | 10 (9–12) | 9 (7–10) | 0.1 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 77 (74–87) | 78 (76–86) | 76 (74–90) | 0.3 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 97 (86–109) | 99 (81–108) | 97 (86–112) | 0.5 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) (n = 27) | 3.1 (2.9–4.1) | 3.1 (2.9–3.2) | 3.0 (2.7–4.0) | 0.6 |

| Norepinephrine dose (mcg/kg/min) (n = 34) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.3 |

| Sedation, n (%) | 19 (45%) | 6 (30%) | 13 (59%) | 0.2 |

| Sufentanil (mcg/kg/h) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 0.4 |

| Midazolam (mg/kg/h) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 0.02 (0.01–0.02) | 0.02 (0.02–0.03) | 0.8 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 197 (161–265) | 172 (132–221) | 198 (178–282) | 0.1 |

| Central venous pressure (mmHg) | 11 (8–14) | 11 (8–13) | 12 (7–15) | 0.9 |

| Lactate concentration (mmol/l) | 1.5 (1.2–2.1) | 1.5 (1.2–2.1) | 1.4 (1.2–2.1) | 0.6 |

| Lactate concentration > 2 mmol/l, n (%) | 11 (26) | 5 (25) | 6 (26) | 0.7 |

| Oliguria (urine output < 0.5 ml/kg/h), n (%) | 42 (100) | 20 (100) | 22 (100) | 0.8 |

| ScvO2 (%) | 71 (69–73) | 71 (69–73) | 70 (68–72) | 0.8 |

| Capillary refill time (seconds) | 2.2 (2.0–2.7) | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | 2.4 (2.0–2.9) | 0.4 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dl) | 9 (7–11) | 10 (9–11) | 9 (8–11) | 0.3 |

| Peripheral perfusion index (PPI) | 2 (0.8–2.3) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 2.1 (0.8–2.3) | 0.6 |

| Fluid removal rate (ml/h) | 100 (100–200) | 100 (100–200) | 150 (100–200) | 0.1 |

| Time between diagnosis of shock and start of fluid removal by CVVHDF (hours) | 34 (24–49) | 45 (36–50) | 26 (14–48) | 0.06 |

| Fluid removal duration (days) | 10 (8–12) | 8 (8–10) | 10 (10–12) | 0.1 |

| Cumulative fluid balance before start of fluid removal by CVVHDF (ml) | 2404 (1368–3777) | 3211 (2026–4000) | 2235 (1368–3289) | 0.2 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 22 (52) | 7 (35) | 15 (68) | 0.03 |

Data are expressed as median with 25th and 75th percentile unless otherwise specified

APACHE II Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, CVVDHF continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration, ScvO2 central venous oxygen saturation, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Hemodynamic and tissue oxygenation parameters during fluid removal with CVVHDF

MAP, CI, ScvO2, PPI and finger temperature did not change significantly during the study period in all patients (Table 2). Norepinephrine dose was higher in group B than in group A (p = 0.02) at T6, and lactate concentration (p = 0.03) increased during the study period only in group B (Table 2). The median time from T0 to the first increase in norepinephrine dose was 120 (70–145) minutes in group B. The MAP at the time of first increase in norepinephrine dose was 16 (10–27)% lower than at baseline.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic parameters during the study period in patients with (group B) and without (group A) altered tissue perfusion

| Parameter | T0 | T1 | T3 | T6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP (mmHg) | ||||

| Group A | 78 (76–86) | 76 (72–86) | 72 (70–83) | 78 (75–82) |

| Group B | 76 (74–90) | 73 (68–79) | 74 (72–86) | 75 (72–87) |

| CI (L/min/m2) (n = 27) | ||||

| Group A | 3.1 (2.9–3.2) | 3.2 (3.0–3.3) | 3.1 (2.9–3.5) | 3.2 (2.7–3.6) |

| Group B | 3.0 (2.7–4.0) | 2.9 (2.7–4.1) | 3.0 (2.7–4.0) | 3.1 (2.9–3.8) |

| Norepinephrine dose (mcg/kg/min) (n = 34) | ||||

| Group A | 0.2 (0.2–0.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) |

| Group B | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.4 (0.3–0.8)#* |

| Lactate concentration (mmol/l) | ||||

| Group A | 1.5 (1.2–2.1) | 1.5 (1.2–2.3) | 1.5 (1.3–2.0) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) |

| Group B | 1.4 (1.2–2.1) | 1.5 (1.3–2.0) | 1.7 (1.5–2.1) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7)#* |

| ScvO2 (%) | ||||

| Group A | 71 (69–72) | 70 (69–74) | 71 (68–72) | 70 (68–71) |

| Group B | 70 (68–71) | 71 (69–73) | 70 (68–74) | 69 (67–71) |

| PPI | ||||

| Group A | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 1.6 (1.2–1.9) | 1.9 (1.5–2.2) | 2.1 (1.3–2.2) |

| Group B | 2.1 (0.8–2.3) | 1.6 (0.9–2.1) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 1.5 (1.2–2.1) |

Data are expressed as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles

CI cardiac index, MAP mean arterial pressure, PPI peripheral perfusion index, ScvO2, central venous oxygen saturation

*p < 0.05 between groups A and B at that time point

#p < 0.05 versus baseline (T0) value in the same group

Change in SBF during fluid removal with CVVHDF

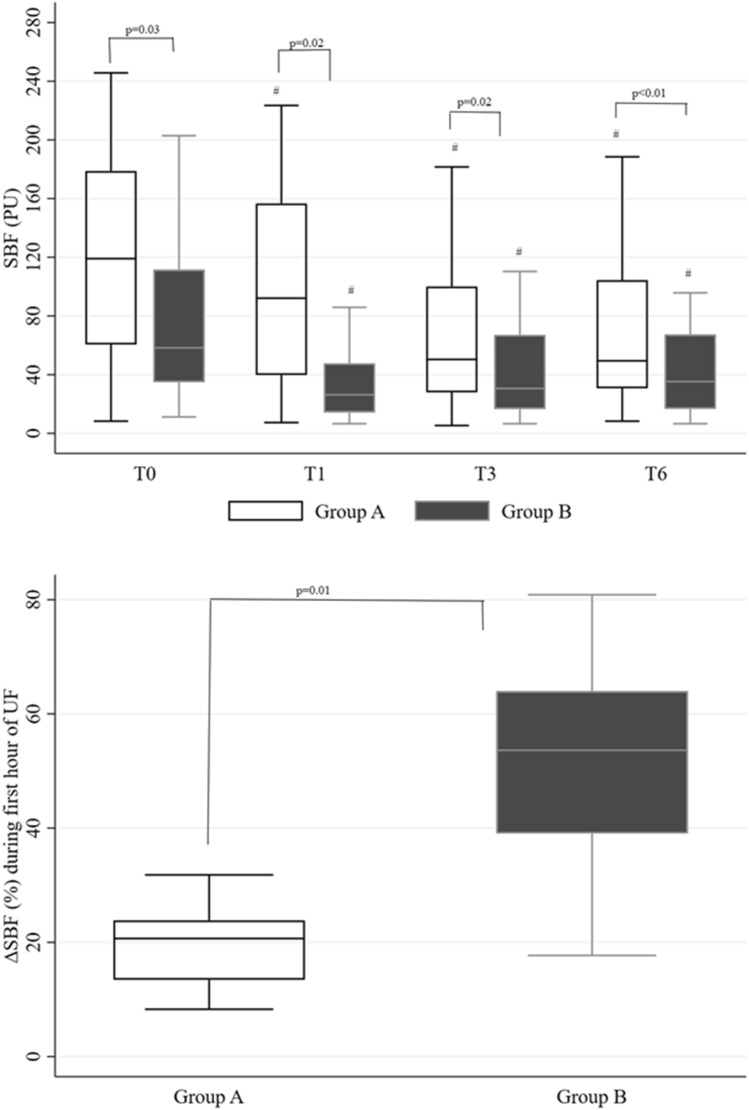

SBF was lower at all time points in group B than in group A (Fig. 1a). SBF decreased in both groups from T0 to T1 (Fig. 1a), but the ∆SBF% during this time period was higher in patients in group B than group A (p = 0.01) (Fig. 1b). SBF was similar in patients with septic shock and cardiogenic shock (Additional file 1: Table S2), and decreased similarly in both groups from T0 to T1 (∆SBF% 32 [15–54]% vs 30 [20–63]%, p = NS). Changes in SBF from T0 to T1 were similar in patients with fluid removal starting at initiation of CVVHDF and those with fluid removal starting later (∆SBF% 28 [18–58]% vs 32 [15–48]%, p = NS) (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Fig. 1.

Box-and-whisker plots (median and interquartile range) of skin blood flow (SBF) during fluid removal with CVVHDF (a) and change in SBF (∆SBF) during the first hour of fluid removal with CVVHDF (UF; b) in the two groups. #p < 0.05 vs baseline (T0) in the same group; PU perfusion unit

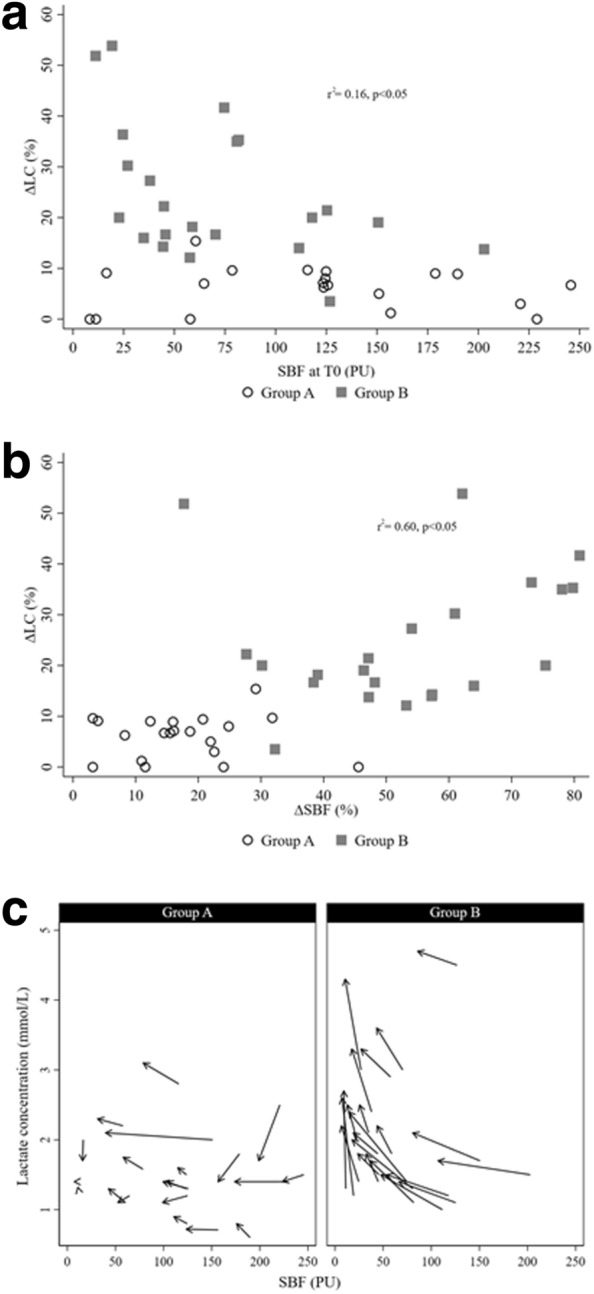

The SBF at T0 (r2 = 0.16, p = 0.04) (Fig. 2a) and the ∆SBF% throughout the study period (r2 = 0.60, p < 0.01) were correlated with the increase in blood lactate concentration during the first 6 h of fluid removal (Fig. 2b). Individual changes in SBF and lactate concentration from the first hour of fluid removal by CVVDHF to the 6th hour are shown in Fig. 2c.

Fig. 2.

Correlations between change in lactate concentration (∆LC%) and a skin blood flow (SBF) at baseline (T0) and b change in SBF over first hour of fluid removal with CVVHDF (∆SBF%); c individual change in SBF and lactate concentration from baseline to 6 h after start of fluid removal with CVVHDF in groups A and B

Variables to predict the presence of altered tissue perfusion

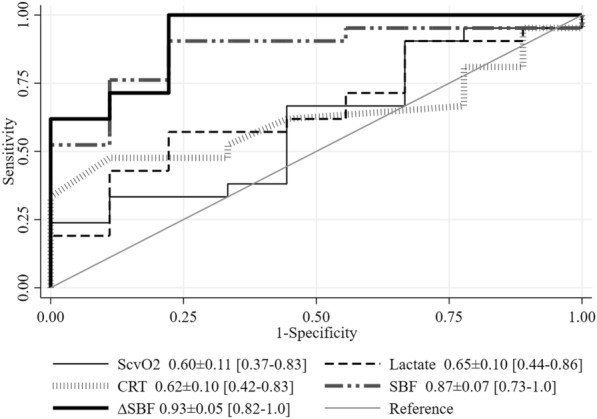

The AUROCs for SBF at T0 (0.87 ± 0.07 [0.73–1.0]) and the ∆SBF% from T0 to T1 (0.93 ± 0.05 [0.82–1.0]) were higher than the AUROCs for other variables (p = 0.01), with cut-off points of ≤ 57 PU (sensitivity 78%, specificity 87%) and ≥ 45% (sensitivity 92%, specificity 99%), respectively (Fig. 3); the AUROC for baseline SBF was similar to that of ∆SBF%. The AUROCs for CI, MAP and norepinephrine dose at T0 were 0.55 ± 0.13 [0.28–0.82], 0.64 ± 0.12 [0.41–0.88], and 0.65 ± 0.13 [0.38–0.92], respectively.

Fig. 3.

Areas under the curve for prediction of change in tissue perfusion (change in lactate concentration ≥ 10% with lactate concentration at T6 ≥ 1.5 mmol/l). ScvO2 central venous oxygen saturation, CRT capillary refill time, SBF skin blood flow, ∆SBF change in SBF from T0–T1

Discussion

In this prospective observational study, SBF at the start of fluid removal using CVVHDF and a decrease in SBF during the first hour of fluid removal were both related to a worsening of tissue perfusion as measured by an increase in lactate concentration at 6 h compared to baseline. Additionally, despite a reduction in SBF during fluid removal by CVVHDF, MAP, CI, PPI and ScvO2 did not change during the study period.

In patients with circulatory shock, increased blood lactate concentration is an indicator of altered tissue perfusion [17, 43, 44] and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [15, 16, 36, 43, 45], including in patients with septic shock [16, 36, 43–46]. Even a mildly elevated lactate concentration, ≥ 1.5 mmol/l, is associated with worse outcomes [16, 47, 48] and related to altered sublingual microcirculatory perfusion [16]. Moreover, dynamic changes in lactate levels during resuscitation are as important as absolute lactate values [43, 49]. A reduction in lactate concentration during the resuscitation period is associated with decreased mortality [44, 50–52], whereas increasing lactate concentrations suggest that treatment should be reassessed [49]. Although the optimal cut-off points for decrease in lactate are debated, Nguyen et al. [14] reported that a lactate reduction ≥ 10% over a 6-h period was related to improved survival, and Jones et al. [53] used a lactate reduction > 10% as a target for resuscitation in their randomized controlled trial in patients with sepsis. In the present study, we therefore chose to define worsening tissue perfusion as an increase in blood lactate concentration of ≥ 10% during a 6-h period, with a T6 lactate of at least 1.5 mmol/l. The change in lactate concentration in patients with altered tissue perfusion may be explained by the occurrence of hemodynamic compromise, as shown by an increase in norepinephrine dose in these patients during the study period.

The stable CI, MAP and ScvO2, despite the decrease in SBF, suggest that finger SBF was more sensitive than systemic hemodynamic variables and ScvO2 for detecting impaired tissue perfusion. ScvO2 did not decrease during fluid removal by CVVHDF as was reported by Zhang et al. [54]. This observation may be explained by a higher ultrafiltration rate in that study [54] compared to ours [1900 ± 800 ml in 3.65 h vs 600 (450–1200) ml in 6 h, respectively]. The PPI also did not decrease in our study as was reported in a study by Klijn et al. [55]. This might again be explained by the different fluid removal rates: in the present study, the fluid removal rate was fixed during the study period, whereas in the study by Klijn et al. [55] it was doubled every 15 min. Bigé et al. [56] observed that an index CRT > 3 s had a reasonably good predictive value for intradialytic hypotension, but this measure was less reliable in our patients (AUC 0.62 vs 0.71), perhaps because we included fewer patients with a CRT > 3 s at baseline (27% vs 55%, respectively).

SBF was lower throughout the study period in patients with altered tissue perfusion. One may argue that the lower SBF in these patients was caused by the higher norepinephrine dose. However, several studies using muscle tissue oxygenation [57] and sublingual microcirculatory assessment [57–59] have shown that norepinephrine does not reduce peripheral tissue perfusion. Moreover, in a recent study [26], we showed that finger SBF, obtained using SLD, was not related to norepinephrine dose in patients with circulatory shock. Therefore, a lower SBF in patients with altered tissue perfusion during the study period was likely to have been associated with the fluid removal process rather than the higher vasopressor doses. Of note, changes in SBF were not more reliable than single SBF values, but these two parameters could guide fluid removal therapy in distinct ways. Patients with higher SBF at baseline appear to have a low risk of developing hemodynamic compromise, and measurement of SBF could thus help physicians select those patients who are suitable for fluid removal therapy. By contrast, the ∆SBF may help adjust the fluid removal rate. From our results, a reduction in SBF of ≥ 45% during the first hour after fluid removal is started should prompt a reduction in the fluid removal rate. Therefore, measuring the SBF at baseline and monitoring the change in SBF over time could help prevent worsening of tissue hypoperfusion during fluid removal by CVVHDF.

The monocenter nature of this study is both an advantage and a limitation. An advantage is the relative homogeneity in procedures. A limitation is that our data may not apply to other units with other protocols in place. Additionally, because of the criteria used to define altered tissue perfusion, we excluded patients who had received propofol because of the potential effect of propofol infusion on lactate concentration [12, 60]. Our observations need to be validated in multicenter studies including larger sample sizes.

Conclusion

A lower SBF at the start of fluid removal using CVVHDF and reduction in SBF over the first hour of treatment are related to the development of new tissue hypoperfusion.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Main characteristics in patients without (group A) and with (group B) altered tissue perfusion at the time of diagnosis of shock. Table S2. Hemodynamic variables and skin blood flow (SBF) during the study period in patients with septic shock and cardiogenic shock. Table S3. Hemodynamic variables and skin blood flow (SBF) during the study period in patients in whom fluid removal was started at the same time as continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) or later

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- CI

Cardiac index

- CVVH

Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration

- CVVHDF

Continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration

- CRT

Capillary refill time

- CVP

Central venous pressure

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- PPI

Peripheral perfusion index

- SBF

Skin blood flow

- SLD

Skin laser Doppler

- ScvO2

Central venous oxygen saturation

- RBC

Red blood cell

Authors’ contributions

WM, JLV, JC designed the study. WM and PB performed the SBF measurements. WM, JLV and JC analyzed the data. WM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PB, JLV and JC revised the article for critical content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the local ethical Committee (Protocol number P2017/013/B406201730812), and informed consent was signed by all patients or their next of kin.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Silversides JA, Fitzgerald E, Manickavasagam US, Lapinsky SE, Nisenbaum R, Hemmings N, et al. Deresuscitation of patients with iatrogenic fluid overload is associated with reduced mortality in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1600–1607. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murugan R, Balakumar V, Kerti SJ, Priyanka P, Chang CH, Clermont G, et al. Net ultrafiltration intensity and mortality in critically ill patients with fluid overload. Crit Care. 2018;22:223. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2163-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murugan R, Kerti SJ, Chang CH, Gallagher M, Clermont G, Palevsky PM, et al. Association of net ultrafiltration rate with mortality among critically ill adults with acute kidney injury receiving continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration: a secondary analysis of the randomized evaluation of normal vs augmented level (RENAL) of renal replacement therapy trail. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e195418. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C, Wald R, Martensson J, Maiden M, et al. Acute kidney injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:816–828. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4755-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald R, Shariff SZ, Adhikari NK, Bagshaw SM, Burns KE, Friedrich JO, et al. The association between renal replacement therapy modality and long-term outcomes among critically ill adults with acute kidney injury: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:868–877. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monnet X, Cipriani F, Camous L, Sentenac P, Dres M, Krastinova E, et al. The passive leg raising test to guide fluid removal in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:46. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0149-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veenstra G, Pranskunas A, Skarupskiene I, Pilvinis V, Hemmelder MH, Ince C, et al. Ultrafiltration rate is an important determinant of microcirculatory alterations during chronic renal replacement therapy. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:71. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0483-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douvris A, Malhi G, Hiremath S, McIntyre L, Silver SA, Bagshaw SM, et al. Interventions to prevent hemodynamic instability during renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2018;22:41. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-1965-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silversides JA, Pinto R, Kuint R, Wald R, Hladunewich MA, Lapinsky SE, et al. Fluid balance, intradialytic hypotension, and outcomes in critically ill patients undergoing renal replacement therapy: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2014;18:624. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0624-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou JA, Streja E, Nguyen DV, Rhee CM, Obi Y, Inrig JK, et al. Intradialytic hypotension, blood pressure changes and mortality risk in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33:149–159. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan L, Zhang H, Meyring-Wosten A, Campos I, Fuertinger D, Thijssen S, et al. Intradialytic central venous oxygen saturation is associated with clinical outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8581. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09233-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraut JA, Madias NE. Lactic acidosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2309–2319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1309483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez G, Bellomo R, Bakker J. The ten pitfalls of lactate clearance in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:82–85. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5213-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Knoblich BP, Jacobsen G, Muzzin A, Ressler JA, et al. Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1637–1642. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000132904.35713.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichol AD, Egi M, Pettila V, Bellomo R, French C, Hart G, et al. Relative hyperlactatemia and hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a retrospective multi-centre study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R25. doi: 10.1186/cc8888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vellinga NAR, Boerma EC, Koopmans M, Donati A, Dubin A, Shapiro NI, et al. Mildly elevated lactate levels are associated with microcirculatory flow abnormalities and increased mortality: a microSOAP post hoc analysis. Crit Care. 2017;21:255. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1842-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou J, Song J, Gong S, Li L, Zhang H, Wang M. Persistent hyperlactatemia-high central venous-arterial carbon dioxide to arterial-venous oxygen content ratio is associated with poor outcomes in early resuscitation of septic shock. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:1136–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert EM, Haupt MT, Mandanas RY, Huaringa AJ, Carlson RW. The effect of fluid loading, blood transfusion, and catecholamine infusion on oxygen delivery and consumption in patients with sepsis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:873–878. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent JL, Roman A, De Backer D, Kahn RJ. Oxygen uptake/supply dependency. Effects of short-term dobutamine infusion. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:2–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Backer D, Creteur J, Dubois MJ, Sakr Y, Koch M, Verdant C, et al. The effects of dobutamine on microcirculatory alterations in patients with septic shock are independent of its systemic effects. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:403–408. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000198107.61493.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chien LCLK, Wo CC, Shoemaker WC. Hemodynamic patterns preceding circulatory deterioration and death after trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62:928–932. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000215411.92950.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Genderen ME, Bartels SA, Lima A, Bezemer R, Ince C, Bakker J, et al. Peripheral perfusion index as an early predictor for central hypovolemia in awake healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:351–356. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318274e151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orbegozo D, Su F, Xie K, Rahmania L, Taccone FS, De Backer D, et al. Peripheral muscle near-infrared spectroscopy variables are altered early in septic shock. Shock. 2018;50:87–95. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orbegozo D, Mongkolpun W, Stringari G, Markou N, Creteur J, Vincent JL, et al. Skin microcirculatory reactivity assessed using a thermal challenge is decreased in patients with circulatory shock and associated with outcome. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:60. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lara B, Enberg L, Ortega M, Leon P, Kripper C, Aguilera P, et al. Capillary refill time during fluid resuscitation in patients with sepsis-related hyperlactatemia at the emergency department is related to mortality. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mongkolpun W, Orbegozo D, Cordeiro CPR, Franco C, Vincent JL, Creteur J. Alterations in skin blood flow at the fingertip are related to mortality in patients with circulatory shock. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:443–450. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez G, Pedreros C, Veas E, Bruhn A, Romero C, Rovegno M, et al. Evolution of peripheral vs metabolic perfusion parameters during septic shock resuscitation. A clinical-physiologic study. J Crit Care. 2012;27:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez G, Luengo C, Bruhn A, Kattan E, Friedman G, Ospina-Tascon GA, et al. When to stop septic shock resuscitation: clues from a dynamic perfusion monitoring. Ann Intensive Care. 2014;4:30. doi: 10.1186/s13613-014-0030-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez G, Ospina-Tascon GA, Damiani LP, Estenssoro E, Dubin A, Hurtado J, et al. Effect of a resuscitation strategy targeting peripheral perfusion status vs serum lactate levels on 28-Day mortality among patients with septic shock: the ANDROMEDA-SHOCK randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:654–664. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salgado MA, Salgado-Filho MF, Reis-Brito JO, Lessa MA, Tibirica E. Effectiveness of laser Doppler perfusion monitoring in the assessment of microvascular function in patients undergoing on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:1211–1216. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eun HC. Evaluation of skin blood flow by laser Doppler flowmetry. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:337–347. doi: 10.1016/0738-081X(95)00080-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schabauer AM, Rooke TW. Cutaneous laser Doppler flowmetry: applications and findings. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:564–574. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)62249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fredriksson I, Larsson M, Strömberg T. Measurement depth and volume in laser Doppler flowmetry. Microvasc Res. 2009;78:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1726–1734. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cecconi M, De Backer D, Antonelli M, Beale R, Bakker J, Hofer C, Jaeschke R, Mebazaa A, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL, Vincent JL, Rhodes A. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1795–1815. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3525-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ait-Oufella H, Lemoinne S, Boelle PY, Galbois A, Baudel JL, Lemant J, et al. Mottling score predicts survival in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:801–807. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2163-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubli S, Waeber B, Dalle-Ave A, Feihl F. Reproducibility of laser Doppler imaging of skin blood flow as a tool to assess endothelial function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36:640–648. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200011000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbink EJ, Wollersheim H, Netten PM, Smits P. Reproducibility of skin microcirculatory measurements in humans, with special emphasis on capillaroscopy. Vascular Med. 2001;6:203–210. doi: 10.1177/1358836X0100600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roustit M, Blaise S, Millet C, Cracowski JL. Reproducibility and methodological issues of skin post-occlusive and thermal hyperemia assessed by single-point laser Doppler flowmetry. Microvasc Res. 2010;79:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryoo SM, Lee J, Lee YS, Lee JH, Lim KS, Huh JW, et al. Lactate level versus lactate clearance for predicting mortality in patients with septic shock defined by Sepsis-3. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e489–e495. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryoo SM, Ahn R, Shin TG, Jo YH, Chung SP, Beom JH, et al. Lactate normalization within 6 hours of bundle therapy and 24 hours of delayed achievement were associated with 28-day mortality in septic shock patients. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0217857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gjesdal G, Braun OÖ, Smith JG, Scherstén F, Tydén P. Blood lactate is a predictor of short-term mortality in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure but without cardiogenic shock. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018;18:8. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0744-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gotmaker R, Peake SL, Forbes A, Bellomo R. Mortality is greater in septic patients with hyperlactatemia than with refractory hypotension. Shock. 2017;48:294–300. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rishu AH, Khan R, Al-Dorzi HM, Tamim HM, Al-Qahtani S, Al-Ghamdi G, et al. Even mild hyperlactatemia is associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2013;17:R197. doi: 10.1186/cc12891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wacharasint P, Nakada TA, Boyd JH, Russell JA, Walley KR. Normal-range blood lactate concentration in septic shock is prognostic and predictive. Shock. 2012;38:4–10. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318254d41a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vincent JL, e Silva AQ, Couto L, Taccone FS. The value of blood lactate kinetics in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016;20:257. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1403-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nichol A, Bailey M, Egi M, Pettila V, French C, Stachowski E, et al. Dynamic lactate indices as predictors of outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2011;15:R242. doi: 10.1186/cc10497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Attaná P, Lazzeri C, Chiostri M, Picariello C, Gensini GF, Valente S. Lactate clearance in cardiogenic shock following ST elevation myocardial infarction: a pilot study. Acute Card Care. 2012;14:20–26. doi: 10.3109/17482941.2011.655293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee SM, Kim SE, Kim EB, Jeong HJ, Son YK, An WS. Lactate clearance and vasopressor seem to be predictors for mortality in severe sepsis patients with lactic acidosis supplementing sodium bicarbonate: a retrospective analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0145181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, Arnold RC, Claremont HA, Kline JA. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739–746. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang H, Chan L, Meyring-Wosten A, Campos I, Preciado P, Kooman JP, et al. Association between intradialytic central venous oxygen saturation and ultrafiltration volume in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33:1636–1642. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klijn E, Groeneveld AB, van Genderen ME, Betjes M, Bakker J, van Bommel J. peripheral perfusion index predicts hypotension during fluid withdrawal by continuous veno-venous hemofiltration in critically ill patients. Blood Purif. 2015;40:92–98. doi: 10.1159/000381939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bigé N, Lavillegrand J-R, Dang J, Attias P, Deryckere S, Joffre J, et al. Bedside prediction of intradialytic hemodynamic instability in critically ill patients: the SOCRATE study. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:47. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00663-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Georger JF, Hamzaoui O, Chaari A, Maizel J, Richard C, Teboul JL. Restoring arterial pressure with norepinephrine improves muscle tissue oxygenation assessed by near-infrared spectroscopy in severely hypotensive septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1882–1889. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dubin A, Pozo MO, Casabella CA, Palizas F, Jr, Murias G, Moseinco MC, et al. Increasing arterial blood pressure with norepinephrine does not improve microcirculatory blood flow: a prospective study. Crit Care. 2009;13:R92. doi: 10.1186/cc7922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jhanji S, Stirling S, Patel N, Hinds CJ, Pearse RM. The effect of increasing doses of norepinephrine on tissue oxygenation and microvascular flow in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1961–1966. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a00a1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mirrakhimov AE, Voore P, Halytskyy O, Khan M, Ali AM. Propofol infusion syndrome in adults: a clinical update. Crit Care Res Pract. 2015;2015:260385. doi: 10.1155/2015/260385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Main characteristics in patients without (group A) and with (group B) altered tissue perfusion at the time of diagnosis of shock. Table S2. Hemodynamic variables and skin blood flow (SBF) during the study period in patients with septic shock and cardiogenic shock. Table S3. Hemodynamic variables and skin blood flow (SBF) during the study period in patients in whom fluid removal was started at the same time as continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) or later

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.