Abstract

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) has potent biological activity as well as strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. This study aims to explore the protective effect of EGCG on LPS-induced acute injury. We randomly divided 18 mice into three groups: CON, LPS, and EGCG-LPS. We gave the EGCG-LPS group gavage treatment with EGCG on day 8–15 and an intraperitoneal injection of LPS on day 16 to induce acute injury. The results showed that, compared with the LPS group, the bodyweight of the mice in the EGCG-LPS group increased significantly and effectively inhibited the morphological damage of the jejunum and liver. We measured liver tissue and found that the EGCG gavage treatment significantly inhibited the pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, MIP-2, IFN-γ) and oxidation indicators (MPO, NO, ALT, and AST) levels increase. The microbiological results showed that the EGCG gavage treatment reshaped the disturbance done to the intestinal microbial community in the mice by LPS, reversed the changes in the abundance ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes, and significantly reduced the abundance of Enterobacteriales. Finally, the serum metabolomics results showed that, when compared with the LPS group, the gavage treatment of EGCG significantly increased the concentration of sphingomyelin (d17:1/17:0), sphingomyelin (d16:1/20:0), and significantly reduced the content of trans-Hexadec-2-enoyl carnitine, and so on. Therefore, we believe that EGCG can protect mice from acute stress induced by LPS while stabilizing gut microbes in general, improving the metabolism of sphingolipids, and inhibiting the content of harmful metabolites.

Keywords: Epigallocatechin gallate, LPS, serum metabolomics, acute injury, intestinal microbes

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a major part of the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria, and it is composed of lipids and polysaccharides. A large amount of experimental data shows that LPS can cause systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (1, 2). It is an endotoxin that can not only be secreted in the form of outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) but can also be released by forming micelles in the bacterial membrane (3). LPS is transported to the cytoplasm of immune cells in the form of OMVs, and inflammatory caspases, as the specific receptors of LPS, can activate the production of downstream pro-inflammatory factors (4). On the other hand, LPS contained in micelles is recognized by TLR4 under the combined action of binding proteins (5). Finally, the danger signal of the stress inflammation induced by LPS will reach the liver from the gastrointestinal tract, portal vein, or arterial blood circulation (6). LPS activates liver immune cells (Kupffer cells), thereby inducing the production of TNF-α and other inflammatory factors, which cause the liver to produce oxidative stress and inflammation (7). In an injured state, the liver will eliminate the damaged organelles through autophagy to reduce apoptosis, maintain the integrity of the tissue genome, and provide energy to ensure cell homeostasis (8). In addition, LPS and its receptor protein, TLR4, can induce small intestine damage and reduce its nutrient absorption capacity, thereby causing an imbalance of the intestinal flora and increasing the intestinal permeability. This process further promotes liver damage (9). This may be why the microbial metabolites after the disorder can promote liver inflammation and fibrosis (10). Therefore, for intestinal microbial homeostasis, we can use intestinal microbes to regulate the liver physiology through the intestinal liver axis (11).

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is one of the most abundant catechins in green tea and is a typical polyphenol flavonoid compound that has eight free hydroxyl groups (12). Extensive studies have shown that EGCG is the most widely active substance in green tea, with antibacterial, antiviral, anti-oxidant, anti-arteriosclerosis, anti-thrombosis, anti-vascular proliferation, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor effects (12, 13). Cancer is the result of the final pathogenic development of inflammation (14). Many inflammatory factors, including pro-inflammatory factors and chemokines, mediate the occurrence of cancer (15, 16). In inhibiting inflammation and cancer, EGCG has shown good performance significantly inhibiting inflammatory cell expression in various cancer cells (17–19). Clinical studies have shown that EGCG can resist the proliferation and migration of human cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of NF-κB and MMP-9 (20) On the other hand, EGCG can maintain the integrity of the epithelial barrier of Caco-2 cells and inhibit the increase in the intestinal epithelial permeability induced by IFN-γ (17). After the gut microbes (including Enterobacter aerogenes, Raoultella planticola, Klebsiella pneumoniae) hydrolysis EGCG, the host gut can absorb these microbial metabolites (21). According to previous studies, after EGCG is hydrolyzed in the intestine, a series of transformations and degradations will occur. Studies have shown that 5-(3,5-dihydroxyphenyl)-4-hydroxyvaleric acid is the main metabolite of EGCG in the intestine, and, after the intestinal microbes degrade EGCG, 5-(3’,5’-dihydroxyphenyl) -γ-valerolactone is absorbed by the body, and its glucuronic acid form is the main urinary metabolite (22). EGCG is first absorbed by the intestine after being ingested, and, in this process, the intestinal flora plays a vital role (23). On the other hand, EGCG also has a significant regulatory effect on the composition of the intestinal microbial community. The addition of EGCG to the diet can reduce the microbial abundances of Alipipes, Anaerotruncu, and Desulfovibrio, which are related to metabolic disorders, and can remedy the malnutrition of the intestinal flora caused by non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. EGCG can also inhibit Prevo and Fusobacterium to regulate the intestinal flora (17). Therefore, we assume that EGCG can maintain the gut microbial community’s structural homeostasis and serum metabolites to reduce an acute host injury. This study explored the protection of EGCG in mice with an acute injury induced by lipopolysaccharide, observed the changes in the intestinal flora and serum metabolites of these mice, and determined the protective effect of EGCG.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

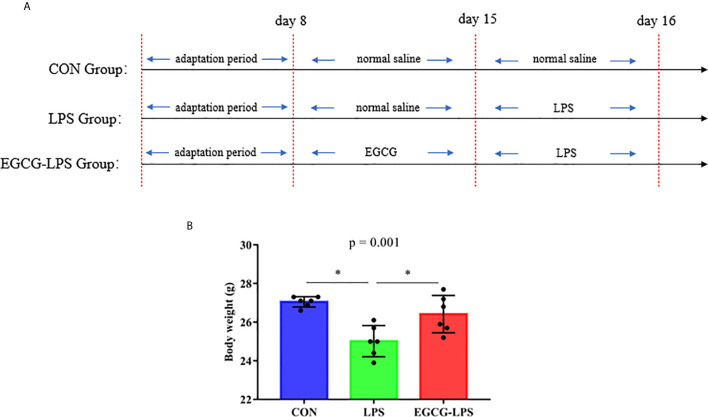

Animal experiments were performed according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Hunan Agricultural University. We selected 18 eight-week-old ICR mice (Hunan Sileike Jingda Co, Changsha, China) for a week of adaptation. On the eighth day, we randomly divided them into three groups: the control group (CON), the LPS model (LPS), and the EGCG gavage treatment group (EGCG-LPS). On days 8–15 of the experiment, according to the pre-experiment results ( Supplemental Figures 1, 2 ), we gave the EGCG-LPS group a gavage of EGCG (200 mg/kg), and the other two groups received normal saline gavage of the same dose. On the 15th day of the experiment, we administered LPS (15 mg/kg) intraperitoneal injections in the mice in the LPS and EGCG-LPS groups as well as intraperitoneal injections of normal saline of the same dose in the CON group ( Figure 1A ). On the 16th day, all mice were sacrificed, serum was collected for metabolome analysis, a portion of the liver and jejunum were fixed in 4% formalin for histomorphological analysis, and a portion of the liver and colon contents were taken, quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and used for liver index determination and 16srDNA determination.

Figure 1.

The protective effects of intragastric administration of EGCG on body weight. (A) the experimental process; (B) body weight. Data are mean ± SD (n = 6) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. “*” means that the horizontal line connects the p-value of the data between the two groups <0.05, and the “P” value in the figure represents the accurate value of p between the three groups of data, and some of the p values between the three groups are too small to be expressed as p<0.0001.

Jejunum and Liver Histopathology

The tissue fixed in 4% formalin was treated with gradient concentrations of xylene and ethanol and then embedded in paraffin. The embedded sample was dehydrated and transparent; it was dyed with hematoxylin and eosin and then covered with neutral gum. The specific process was based on our previous research (24).

Determination of Proinflammatory Factors and Oxidative Stress Substances in Liver Tissue

The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, MIP-2, IFN-γ and MPO in the liver tissue samples were measured by a Mouse ELISA Kit (Jiangsu Yutong Biological Technology Co) with a microplate reader (Bio Tek, USA). The concentration of NO as well as the enzyme activity of ALT and AST in the liver tissue samples were respectively measured by a Nitric Oxide (NO) assay kit (Microwell plate method), Alanine aminotransferase Assay Kit and Aspartate aminotransferase Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) with a microplate reader (Bio Tek, USA).

Serum Metabolomic Analyses

We extracted the serum with methanol and add dichlorophenylalanine. After mixing the liquid, we centrifuged it to obtain the supernatant and perform an on-machine test of LC-MS. The specific chromatographic column and liquid phase conditions used referred to our previous research. The off-machine data was preprocessed with Compound Discoverer software to obtain the molecular weight, mass-to-charge ratio, retention time, and peak area. Finally, we used SIMCA14.1 to perform orthogonal partial least squares discrimination analysis on the data to obtain the VIP value. We used the Human Metabolome Database (https://hmdb.ca/spectra/ms/search) for substance comparison.

16S Ribosomal RNA Amplicon Sequencing

We used the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit to extract microbial genomic DNA from the colon contents. We selected the V3-V4 region sequence of 16S rDNA for high-throughput sequencing analysis on the Illumina platform. The specific process was based on our previous research (24). We then used Trimmomatic software to perform quality control and optimization of the off-machine data before finally performing operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering to determine the composition of the microbial communities at different taxonomic levels. Additionally, we used mothur (Version 1.33.3) to perform alpha diversity analysis. The composition of the microbial community was generated by BMKCloud (http://www.biocloud.net/). The abundance of the sequenced microorganisms at different taxonomic levels was uploaded to http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy for linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and LDA effect size (LEfSe) analysis.

Data Analysis

All of the data in this study are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0. The differences between the means of the experimental groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s multiple comparison test. A p value < 0.05 was regarded as a significant difference.

Results

EGCG Improves the Acute Injury Induced by LPS in Mice

Before the last intraperitoneal injection of LPS, we administered EGCG gavage for 7 consecutive days. The results showed that: compared with the CON group, the intraperitoneal injection of LPS significantly reduced the weight of the mice. But the mice that received EGCG gavage treatment, compared with the LPS group, the weight was significantly increased and avoid the weight loss of mice ( Figure 1B , p < 0.05).

EGCG Inhibits the Development of Acute Injury Induced by LPS

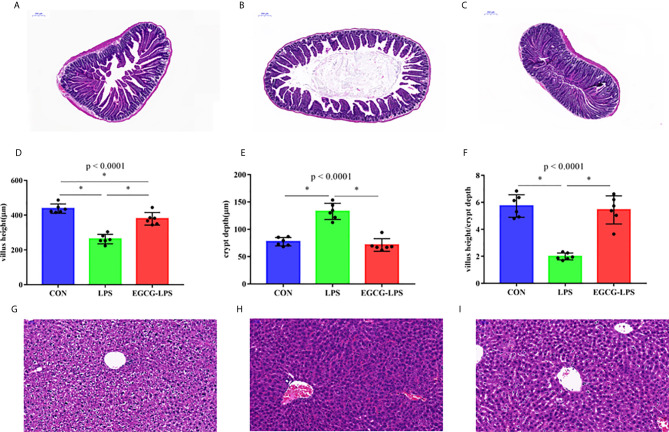

The results of jejunum histomorphology analysis ( Figures 2A–F ) showed that, compared with the CON group, the intraperitoneal injection of LPS caused a significant decrease in the height of the mouse jejunum villi and a significant increase in the depth of the crypts (p < 0.05). However, EGCG-LPS group, compared with the LPS group, the mice had significantly increased villus heights, while the crypt depth was reduced considerably (p < 0.05). It returned to a normal level similar to that of the CON group. The morphological results of the liver tissue ( Figures 2G–I ) showed that the liver cells in the CON group were arranged regularly and neatly centered around the central vein. The liver cells in the LPS group showed apparent inflammatory damage, and the cells were arranged irregularly and exhibited inflammatory infiltration. These damages phenomena were greatly alleviated in the EGCG-LPS group.

Figure 2.

The protective effect of intragastric administration of EGCG on jejunum tissue and liver tissue damage. Images of colon morphology in the CON (A), LPS (B), and LPS-EGCG (C) groups under 200× visual fields; villus height (D), crypt depth (E) and villus height/crypt depth (F) in the three groups; Images of liver morphology in the CON (G), LPS (H), and EGCG-LPS (I) groups under 200× visual fields; Data are mean ± SD (n = 6) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. “*” means that the horizontal line connects the p-value of the data between the two groups <0.05, and the “P” value in the figure represents the accurate value of p between the three groups of data, and some of the p values between the three groups are too small to be expressed as p<0.0001.

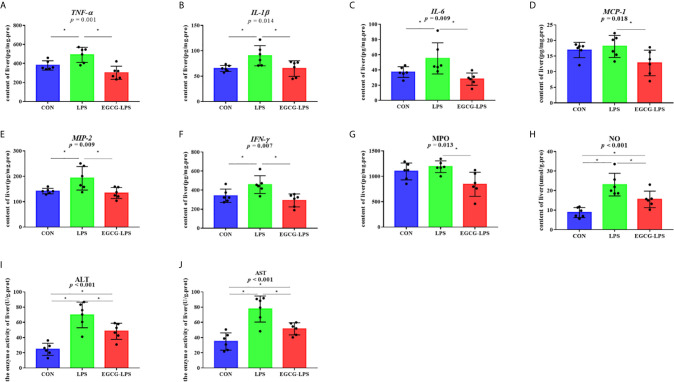

EGCG Inhibits Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Liver Tissue

We measured the concentration of inflammatory factors in the liver tissues ( Figures 3A–F ), and the results showed that, when compared with the CON group, the intraperitoneal injection of LPS significantly increased the concentration of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-2, and IFN-γ in the liver tissue (p < 0.05). However, in the EGCG-LPS group received EGCG gavage protection, compared with the LPS group, the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, MIP-2, IFN-γ in the liver tissues of the mice were significantly reduced (p < 0.05). The oxidative stress index of the mouse liver tissue ( Figures 3G–J ) showed that, when compared with the CON group, the concentration of NO as well as the enzyme activity of ALT and AST in the liver tissue of the LPS group increased significantly (p < 0.05). Compared with the LPS group, the concentration of NO and MPO as well as the enzyme activity of ALT and AST in the mice’s liver tissue after receiving the EGCG treatment decreased significantly (p < 0.05). However, the alleviation of this oxidative stress index did not return to the same level as the CON group.

Figure 3.

The inhibition of the intragastric administration of EGCG on inflammation and oxidative stress in liver tissue. (A) the concentration of TNF-α in liver tissue; (B) the concentration of IL-1β in liver tissue; (C) the concentration of IL-6 in liver tissue; (D) the concentration of MCP-1 in liver tissue; (E) the concentration of MIP-2 in liver tissue; (F) the concentration of IFN-γ in liver tissue; (G) the concentration of MPO in liver tissue; (H) the concentration of total NO in liver tissue; (I) the enzyme activity of ALT in liver tissue; (J) the enzyme activity of AST in liver tissue. Data are mean ± SD (n = 6) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA.”*” means that the horizontal line connects the p-value of the data between the two groups <0.05, and the “P” value in the figure represents the accurate value of p between the three groups of data, and some of the p values between the three groups are too small to be expressed as p<0.0001.

EGCG Regulates Intestinal Microbes in Mice With Acute Injury Induced by LPS

We first analyzed the 16S rRNA V3-V4 region sequence of colonic microorganisms to obtain the α diversity of intestinal microorganisms ( Figures 4A–F ). Compared with the CON group, the observed species, Shannon index, Simpson index, Chao index, and ACE index in the LPS group all decreased significantly (p < 0.05). However, in the mice that received the EGCG treatment, compared with the LPS group, the observed species, Shannon index, Simpson index, Chao index, and ACE index were significantly improved (p < 0.05). Therefore, EGCG gavage can significantly protect mice from the decrease in intestinal microbial diversity caused by LPS.

Figure 4.

The protective effect of the intragastric administration of EGCG on mouse gut microbial diversity. (A) Observed Species; (B) Shannon index; (C) Simpson index; (D) Chao index; (E) ACE index; (F) PD-whole-tree index. Data are mean ± SD (n = 6) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. “*” means that the horizontal line connects the p-value of the data between the two groups <0.05, and the “P” value in the figure represents the accurate value of p between the three groups of data, and some of the p values between the three groups are too small to be expressed as p<0.0001.

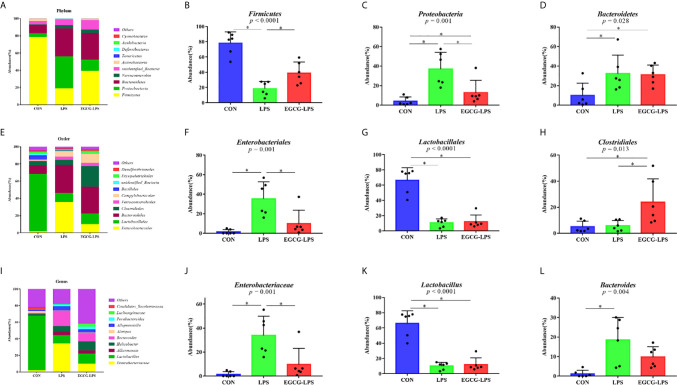

The microbial community composition of the mouse colon ( Figures 5A–D ) showed that Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes were the three main microorganisms at the phylum level. The abundance of these three microorganisms accounts for more than 85% of all microorganisms. The Firmicutes abundance in the CON, LPS, and EGCG-LPS groups were 78.24656%, 18.58981%, and 39.05929%, respectively. Proteobacteria abundance accounted for 4.079801%, 37.06216%, and 12.85193%, respectively. The Bacteroidetes abundance was 9.898671%, 32.38386%, and 31.01083%, respectively. Compared with the CON group, the abundance of Firmicutes in the LPS group was significantly reduced (p < 0.05), but the abundance of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes was significantly increased (p < 0.05). Compared with the LPS group, the abundance of Firmicutes in the EGCG-LPS group was significantly increased (p < 0.05), but the abundance of Proteobacteria was significantly reduced (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The protective effect of the intragastric administration of EGCG on the intestinal microflora of mice. (A) Relative abundance of gut microbiota phyla; (B) percentage of Firmicutes in each sample from the three groups; (C) percentage of Proteobacteria in each sample from the three groups; (D) percentage of Bacteroidetes in each sample from the three groups; (E) relative abundance of gut microbiota orders; (F) percentage of Enterobacteriales in each sample from the three groups; (G) percentage of Lactobacillales in each sample from the three groups; (H) percentage of Clostridiales in each sample from the three groups; (I) relative abundance of gut microbiota genus; (J) percentage of Enterobacteriaceae in each sample from the three groups; (K) percentage of Lactobacillus in each sample from the three groups; (L) percentage of Bacteroides in each sample from the three groups. *p<0.05”*” means that the horizontal line connects the p-value of the data between the two groups <0.05, and the “P” value in the figure represents the accurate value of p between the three groups of data, and some of the p values between the three groups are too small to be expressed as p<0.0001.

The microbial community composition of the mouse colon ( Figures 5E–H ) showed that Lactobacillales, Bacteroidales, and Clostridiales were the three main microorganisms at the order level. The abundance of these three microorganisms accounts for more than 80% of all microorganisms. The Lactobacillales abundance in the CON, LPS, and EGCG-LPS groups were 66.42404%, 10.58623%, and 12.08513%, respectively. The Bacteroidales abundance was 9.873076%, 32.36142%, and 30.93685%, respectively. The Clostridiales abundance was 5.006486%, 5.806248%, and 24.00442%, respectively. Compared with the CON group, the abundance of Lactobacillales in the LPS group was significantly reduced (p < 0.05), but the abundance of Enterobacteriales was significantly increased (p < 0.05). Compared with the LPS group, the abundance of Clostridiales in the EGCG-LPS group was significantly increased (p < 0.05), but the abundance of Enterobacteriales was significantly reduced (p < 0.05).

The microbial community composition of the mouse colon ( Figures 5I–L ) showed that Enterobacteriaceae, Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, Helicobacter, and Bacteroides were the five main microorganisms at the genus level. The abundance of these five microorganisms accounts for more than 70% of all microorganisms. The Enterobacteriaceae abundance in the CON, LPS, and EGCG-LPS groups was 1.453315%, 33.92974%, and 9.697065%, respectively. The Lactobacillus abundance was 66.11865%, 10.09782%, and 11.92314%, respectively. The Akkermansia abundance was 0.545563%, 3.846639%, and 3.939904%, respectively. The Helicobacter abundance was 1.53536%, 6.888258%, and 10.97262%, respectively. The Bacteroides abundance was 1.146524%, 18.53617%, and 9.785772%, respectively. Compared with the CON group, the abundance of Lactobacillus in the LPS group was significantly reduced (p < 0.05), but the abundances of Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroides were significantly increased (p < 0.05). Compared with the LPS group, the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae in the EGCG-LPS group was significantly reduced (p < 0.05).

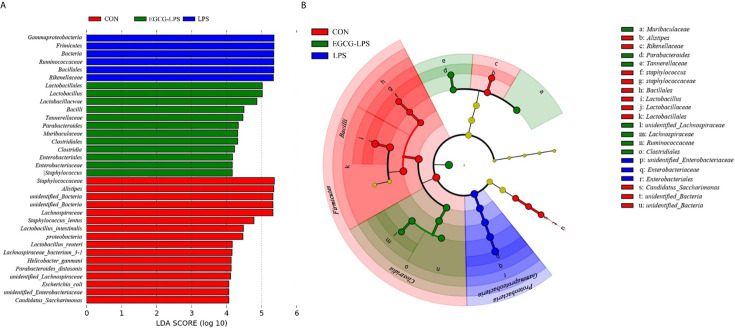

We used linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to estimate the effect of the abundance of each component (species) on the difference effects ( Figure 6A ). LEfSe analysis ( Figure 6B ) showed that the CON group was significantly enriched in Lactobacillus, Lactobacillaceae and Lactobacillales. The LPS group was significantly enriched in Enterobacteriaceae and Enterobacteriales. Meanwhile, the EGCG-LPS group was significantly enriched in Clostridiales.

Figure 6.

Characteristic of mouse colon microorganisms determined by intragastric administration of EGCG. (A) LDA score, an LDA score higher than 4 was considered to be an important contributor to the model; (B) LEfSe taxonomic cladogram, different colors suggest enrichment of certain taxa in the control group (red), LPS group (blue) and LPS-EGCG group (green).

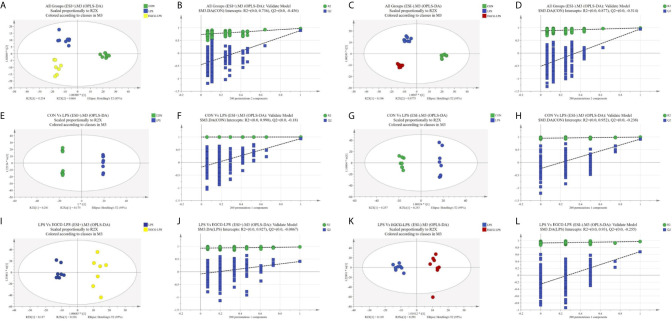

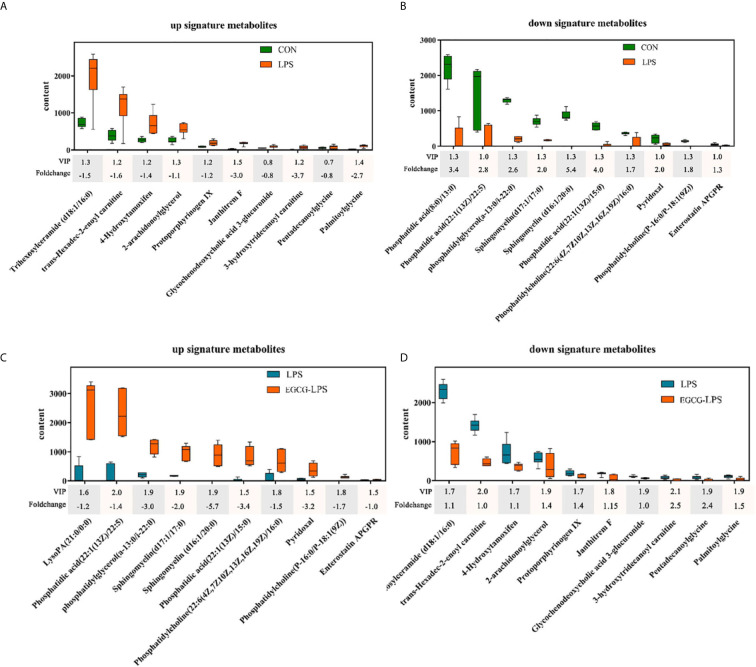

EGCG Affects the Serum Metabolomic Profiles During Acute Injury

We used GC-MS to determine the serum metabolites from the acute injury induced by LPS in the mice. First, we used orthogonal partial least squares discrimination analysis (OPLS-DA) to establish a model of the relationship between metabolite expression and sample category to predict the sample category. At the same time, we also verified this model. The results showed that the serum metabolites of the different groups changed significantly, and the similarity of these metabolisms within each group was high ( Figure 7 ). We specifically analyzed the different metabolites between the CON and LPS groups. We found that the serum levels of the Trihexosylceramide (d18:1/16:0), trans - Hexadec - 2 - enoyl carnitine, 4 - Hydroxytamoxifen, 2 - arachidonoylglycerol, Protoporphyrinogen IX, Janthitrem F, Glycochenodeoxycholic acid 3 - glucuronide, 3 - hydroxytridecanoyl carnitine, Pentadecanoylglycine and Palmitoylglycine significantly increased after the acute injury induced via LPS in the mice ( Figure 8A , p < 0.05). On the other hand, the injection of LPS significantly reduced the phosphatidic acid (18:0/13:0), phosphatidic acid (22):1(13Z)/22:5), phosphatidylglycerol (a-13:0/i-22:0), sphingomyelin (d17:1/17:0), sphingomyelin (d16:1/20:0), phosphatidic acid (22:1(13Z)/15:0), phosphatidylcholine (22:6(4Z,7Z10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)/16:0), pyridoxal, phosphatidylcholine (P-16:0/P-18:1(9Z)) as well as the enterostatin APGPR content ( Figure 8B , p < 0.05). However, under the protection of EGCG gavage, the serum metabolites of mice were not greatly affected by the acute stress induced by LPS ( Figures 8C , D , p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Plots of the multivariate statistical comparisons between groups. (A) OPLS-DA score plot of all groups (ESI+); (B) OPLS-DA (Validate Model) score plot of all groups (ESI+); (C) OPLS-DA score plot of all groups (ESI-); (D) OPLS-DA (Validate Model) score plot of all groups (ESI-); (E) OPLS-DA score plot of CON Vs LPS (ESI+); (F) OPLS-DA (Validate Model) score plot of CON Vs LPS (ESI+); (G) OPLS-DA score plot of CON Vs LPS (ESI-); (H) OPLS-DA (Validate Model) score plot of CON Vs LPS (ESI-); (I) OPLS-DA score plot of LPS Vs LPS-EGCG (ESI+); (J) OPLS-DA (Validate Model) score plot of LPS Vs LPS-EGCG (ESI+); (K) OPLS-DA score plot of LPS Vs LPS-EGCG (ESI-); (L) OPLS-DA (Validate Model) score plot of LPS Vs LPS-EGCG (ESI-).

Figure 8.

The regulatory effect of the intragastric administration of EGCG on mouse serum metabolites. (A) Compared with the CON group, ten characteristic metabolites increased in the LPS group; (B) Compared with the CON group, ten characteristic metabolites reduced in the LPS group; (C) Compared with the LPS group, ten characteristic metabolites increased in the EGCG-LPS group; (D) Compared with the LPS group, ten characteristic metabolites reduced in the EGCG-LPS group.

Discussion

This study explored the protective effect of EGCG on LPS-induced acute injury. We observed that EGCG can significantly prevent the morphological damage done to the jejunum and liver caused by LPS. At the same time, EGCG gavage treatment can also significantly inhibit LPS-induced liver inflammation and oxidative stress. The 16srDNA results show that EGCG can maintain the structure of the intestinal microbial community and inhibit the abundance of enteric pathogens, such as Enterobacteriaceae. Via serum metabolomics analysis, we posit that glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid substances are promoted by EGCG, thereby improving the organism’s immune function.

Polyphenols have been widely used to improve the We found that the gavage of EGCG significantly increased the content of pyridoxal in the serum of the mice, thereby enhancing their ability to reduce the expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and other pro-inflammatory factors while also enhancing the organisms’ immunity due to their good biological activity (25–27). Studies have shown that polyphenols, including EGCG and theaflavin-3′-O-gallate (TF3′G), are absorbed in the jejunum after being ingested (28). Therefore, the nutrient absorption capacity of the jejunum is particularly important for the bioavailability of EGCG. T The jejunal epithelium can be renewed in three days, and the cells on the intestinal villi are replaced via the proliferation of crypt cells (29). The role of the intestinal villi is to increase the area of absorption while also promoting absorption (30). Extensive studies have shown that the acute damage done by LPS to the organism can lead to the destruction of the intestinal integrity and barrier function (31, 32). Our research shows that gavage treatment with EGCG can protect the jejunum’s structural integrity and its ability to absorb nutrients so that it will not be affected by an acute injury caused by LPS. When LPS enters the organism, TLR4 in the liver cells can actively recognize LPS and activate the expression of downstream pro-inflammatory factors (33). Pro-inflammatory factors, including the IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-1 family are widely expressed in the liver, which further deepens the inflammatory damage done to the liver (34). Our research shows that EGCG can well inhibit LPS from activating TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, MIP-2, and IFN-γ. Although the concentration of MCP-1 and MPO was not statistically significant between the CON and LPS groups, from a data point of view, these two indicators still showed an upward trend between these two groups, which proves that LPS induced the occurrence of acute stress. Moreover, under the protection of EGCG, these two indicators were significantly reduced when compared with the LPS group, and, at the same time, there was no significant difference between the EGCG group and CON group.

After being injured, the liver will feedback this stress to the intestine through the portal vein, and this process reshapes the structure of the intestinal microbial community (35). Henao-Mejia’s research team found that the immersion of a large number of Toll-like receptors in the portal vein can significantly promote the expression of TNF-α and further induce the development of liver inflammation damage (36). After this signal pathway is transmitted from the portal vein into the intestine, it leads to the intestinal microbes’ structural changes. Bacterial genera, bacteroides, and Ruminococcus are significantly increased, while Prevotella is significantly reduced (37). Our research also found that the intraperitoneal injection of LPS significantly increased the abundance of bacterial genera and Bacteroides. Although the gavage of EGCG failed to inhibit the increase in the abundance of Bacteroides, it did regulate Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes. This ratio is also a characteristic of the stability of the intestinal microbial community (38). However, EGCG treatment given by oral gavage did not prevent the decrease in the abundance of Lactobacillales, similarly to the previous report showing that diet supplementation with EGCG has a small effect on the abundance of Bifidobacteria (39). Gut microbes play an irreplaceable role in intestinal immunity. Proteobacteria is the intestinal microorganism known to be the most relevant to diseases (40). Most of the microorganisms belonging to this phylum level are human pathogens. An increasing number of studies have found that Proteobacteria is an important cause of intestinal inflammation and metabolic disease (41, 42). In this experiment, the gavage treatment of EGCG significantly reduced the abundance of Proteobacteria underwater at the portal level, thereby reducing the risk of intestinal inflammation in the mice. Enterobacteriales is an order under Gamma-proteobacteria, which is under Proteobacteria. The gavage treatment of EGCG also suppressed the abundance of such pathogenic bacteria. EGCG can inhibit the expression of stx1 and RecA in enterobacteria membrane cells and induce the expression of stx2 and oxyR by increasing the oxidative stress response, thereby increasing the permeability of the outer membrane and leading to the inactivation of Enterobacter (43).

As an important part of systems biology, metabonomics is used in the prediction of the effects of diseases and tumor drugs as well as the detection of markers (44). Sphingolipids are an essential part of the structure of biological membranes, and an increasing number of studies have shown that they are closely related to immunity and inhibiting inflammation (45, 46). Sphingomyelin metabolites can reduce the ability of TNF to induce CCL5 and minimize the risk of inflammation. Our research showed that, under the protection of EGCG gavage, the serum levels of sphingomyelin (d17:1/17:0) and sphingomyelin (d16:1/20:0) were not affected by the LPS-induced acute injury. Pyridoxal is an active form of vitamin B6, which has always been regarded as an important substance for improving immune function and reducing inflammation (47). We found that the gavage of EGCG significantly increased the content of pyridoxal in the serum of the mice, thereby enhancing their ability to reduce the expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and other pro-inflammatory factors while also enhancing the organisms’ immunity. More importantly, previous studies have shown that vitamins have an inhibitory effect on the Stx2 production of Enterobacteriales, which reduces the growth and virulence potential of this type of intestinal pathogenic bacteria (48). This corresponds to the fact that under the protection of EGCG gavage in our experiment, the abundance of Enterobacteriales in the colon is significantly reduced. On the other hand, the reduction of harmful substances also reflects the effect of EGCG gavage therapy, which significantly reduced the content of trans-Hexadec-2-enoyl carnitine in the serum of the mice with LPS-induced inflammation. Trans-Hexadec-2-enoyl carnitine is a kind of acylcarnitine. The accumulation of acylcarnitine in the body promotes the expression of pro-inflammatory factors in the organism and induces the phosphorylation of JNK and ERK (49). Studies have also found that an increased concentration of acylcarnitine increases the risk of intestinal permeability. It can be seen that the gavage treatment of EGCG significantly increased the content of immune-enhancing substances in the blood and inhibited the connection between harmful substances and inflammation.

Conclusions

Our experimental results show that the gavage of EGCG can effectively prevent the negative effects of LPS-induced acute injury. On the other hand, EGCG can stabilize the intestinal microbial community structure of mice in general and reduce pathogenic bacteria, such as Proteus and Enterobacter. Moreover, EGCG can regulate serum metabolite components; promote the production of beneficial metabolomes, including sphingomyelin (d17:1/17:0), sphingomyelin (d16:1/20:0); and reduce the production of these harmful metabolomes, including trans-Hexadec-2-enoyl carnitine. Therefore, EGCG can significantly inhibit the acute injury induced by LPS and improve the immune function of the organism.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, SUB8703003.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of Hunan Agricultural University.

Author Contributions

YM performed the study and conducted data analysis. GL designed the research. MT provided assistance for the study. HJ and JF prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31772642, 31672457, 41807135), Local Science and Technology Development Project Guided by The Central Government (YDZX20184300002303, 2018CT5002), and Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department (2019TP2004, 2018WK4025, 2020NK2004, 2020ZL2004, 2016NK2101, 2016TP2005, 2018CT5002), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M632963, 2019T120705), Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department (2020JGYB112, 18B107), Double first-class construction project of Hunan Agricultural University (SYL201802003, YB2018007, CX20190497), and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan province, China (No. 2019JJ50220).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.640305/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Cribbs SK, Martin GS. Expanding the global epidemiology of sepsis. Crit Care Med (2007) 35(11):2646–8. 10.1097/01.Ccm.0000288082.99980.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Geng C, Guo Y, Wang C, Cui C, Han W, Liao D, et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Changes in Rats Based on Metabolomics. J Inflammation Res (2020) 13:477–86. 10.2147/jir.S266012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Romerio A, Peri F. Increasing the Chemical Variety of Small-Molecule-Based TLR4 Modulators: An Overview. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1210. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vanaja SK, Russo AJ, Behl B, Banerjee I, Yankova M, Deshmukh SD, et al. Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles Mediate Cytosolic Localization of LPS and Caspase-11 Activation. Cell (2016) 165(5):1106–19. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huber RG, Berglund NA, Kargas V, Marzinek JK, Holdbrook DA, Khalid S, et al. A Thermodynamic Funnel Drives Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Transfer in the TLR4 Pathway. Structure (London Engl 1993) (2018) 26(8):1151–61.e4. 10.1016/j.str.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strnad P, Tacke F, Koch A, Trautwein C. Liver - guardian, modifier and target of sepsis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2017) 14(1):55–66. 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Signalling pathways in alcohol-induced liver inflammation. J Hepatol (2009) 50(6):1258–66. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu C, Zhao L, Shen M, Wu Z, Li L. Autophagy regulation is an effective strategy to improve the prognosis of chemically induced acute liver injury based on experimental studies. J Cell Mol Med (2020) 24(15):8315–25. 10.1111/jcmm.15565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu LX, Schwabe RF. The gut microbiome and liver cancer: mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2017) 14(9):527–39. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Minicis S, Rychlicki C, Agostinelli L, Saccomanno S, Candelaresi C, Trozzi L, et al. Dysbiosis contributes to fibrogenesis in the course of chronic liver injury in mice. Hepatol (Baltimore Md) (2014) 59(5):1738–49. 10.1002/hep.26695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Acharya C, Bajaj JS. Altered Microbiome in Patients With Cirrhosis and Complications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc (2019) 17(2):307–21. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chakrawarti L, Agrawal R, Dang S, Gupta S, Gabrani R. Therapeutic effects of EGCG: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Patents (2016) 26(8):907–16. 10.1080/13543776.2016.1203419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu B, Yan W. Lipophilization of EGCG and effects on antioxidant activities. Food Chem (2019) 272:663–9. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature (2008) 454(7203):436–44. 10.1038/nature07205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature (2002) 420(6917):860–7. 10.1038/nature01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol (2014) 15(11):e493–503. 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70263-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gil-Cardoso K, Ginés I, Pinent M, Ardévol A, Blay M, Terra X. Effects of flavonoids on intestinal inflammation, barrier integrity and changes in gut microbiota during diet-induced obesity. Nutr Res Rev (2016) 29(2):234–48. 10.1017/s0954422416000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jhang JJ, Lu CC, Yen GC. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits urate crystals-induced peritoneal inflammation in C57BL/6 mice. Mol Nutr Food Res (2016) 60(10):2297–303. 10.1002/mnfr.201600106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rajagopal C, Lankadasari MB, Aranjani JM, Harikumar KB. Targeting oncogenic transcription factors by polyphenols: A novel approach for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Res (2018) 130:273–91. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luo KW, Wei C, Lung WY, Wei XY, Cheng BH, Cai ZM, et al. EGCG inhibited bladder cancer SW780 cell proliferation and migration both in vitro and in vivo via down-regulation of NF-κB and MMP-9. J Nutr Biochem (2017) 41:56–64. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gan RY, Li HB, Sui ZQ, Corke H. Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): An updated review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2018) 58(6):924–41. 10.1080/10408398.2016.1231168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Z, de Bruijn WJC, Bruins ME, Vincken JP. Microbial Metabolism of Theaflavin-3,3’-digallate and Its Gut Microbiota Composition Modulatory Effects. J Agric Food Chem (2021) 69(1):232–45. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu AB, Tao S, Lee MJ, Hu Q, Meng X, Lin Y, et al. Effects of gut microbiota and time of treatment on tissue levels of green tea polyphenols in mice. BioFactors (Oxford England) (2018) 44(4):348–60. 10.1002/biof.1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ma Y, Hu C, Yan W, Jiang H, Liu G. Lactobacillus pentosus Increases the Abundance of Akkermansia and Affects the Serum Metabolome to Alleviate DSS-Induced Colitis in a Murine Model. Front Cell Dev Biol (2020) 8:591408. 10.3389/fcell.2020.591408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ding S, Jiang H, Fang J. Regulation of Immune Function by Polyphenols. J Immunol Res (2018) 2018:1264074. 10.1155/2018/1264074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang K, Jin X, Li Q, Sawaya A, Le Leu RK, Conlon MA, et al. Propolis from Different Geographic Origins Decreases Intestinal Inflammation and Bacteroides spp. Populations in a Model of DSS-Induced Colitis. Mol Nutr Food Res (2018) 62(17):e1800080. 10.1002/mnfr.201800080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ding S, Xu S, Fang J, Jiang H. The Protective Effect of Polyphenols for Colorectal Cancer. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1407. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nguyen HN, Tanaka M, Li B, Ueno T, Matsuda H, Matsui T. Novel in situ visualisation of rat intestinal absorption of polyphenols via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation mass spectrometry imaging. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):3166. 10.1038/s41598-019-39405-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jeurissen SH, Lewis F, van der Klis JD, Mroz Z, Rebel JM, ter Huurne AA. Parameters and techniques to determine intestinal health of poultry as constituted by immunity, integrity, and functionality. Curr Issues Intestinal Microbiol (2002) 3(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zheng Z, Zuo Z, Zhu P, Wang F, Yin H, Peng X, et al. A study on the expression of apoptotic molecules related to death receptor and endoplasmic reticulum pathways in the jejunum of AFB(1)-intoxicated chickens. Oncotarget (2017) 8(52):89655–64. 10.18632/oncotarget.20333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang Y, Deng Q, Zhang Z, Zhao H, Tang J, Chen X, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 2 attenuates intestinal mucosal barrier injury through the MLCK/pMLC signaling pathway in a piglet model. J Cell Physiol (2021) 236(4):3015–32. 10.1002/jcp.30068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen F, Wang H, Chen J, Liu Y, Wen W, Li Y, et al. Lactobacillus delbrueckii Ameliorates Intestinal Integrity and Antioxidant Ability in Weaned Piglets after a Lipopolysaccharide Challenge. Oxid Med Cell Longevity (2020) 2020:6028606. 10.1155/2020/6028606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jia L, Vianna CR, Fukuda M, Berglund ED, Liu C, Tao C, et al. Hepatocyte Toll-like receptor 4 regulates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Commun (2014) 5:3878. 10.1038/ncomms4878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ge Y, Huang M, Yao YM. Autophagy and proinflammatory cytokines: Interactions and clinical implications. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2018) 43:38–46. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Albillos A, de Gottardi A, Rescigno M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J Hepatol (2020) 72(3):558–77. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin C, Hao L, Mehal WZ, Strowig T, et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature (2012) 482(7384):179–85. 10.1038/nature10809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boursier J, Mueller O, Barret M, Machado M, Fizanne L, Araujo-Perez F, et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatol (Baltimore Md) (2016) 63(3):764–75. 10.1002/hep.28356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grigor’eva IN. Gallstone Disease, Obesity and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio as a Possible Biomarker of Gut Dysbiosis. J Personalized Med (2020) 11(1):13. 10.3390/jpm11010013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Unno T, Sakuma M, Mitsuhashi S. Effect of dietary supplementation of (-)-epigallocatechin gallate on gut microbiota and biomarkers of colonic fermentation in rats. J Nutr Sci Itaminol (2014) 60(3):213–9. 10.3177/jnsv.60.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shin NR, Whon TW, Bae JW. Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol (2015) 33(9):496–503. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007) 104(34):13780–5. 10.1073/pnas.0706625104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology (2008) 134(2):577–94. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang J, Tang CB, Xiao J, Du WF, Li R. Influences of epigallocatechin gallate and citric acid on Escherichia coli O157:H7 toxin gene expression and virulence-associated stress response. Lett Appl Microbiol (2018) 67(5):435–41. 10.1111/lam.13058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spratlin JL, Serkova NJ, Eckhardt SG. Clinical applications of metabolomics in oncology: a review. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2009) 15(2):431–40. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-08-1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol (2008) 8(10):753–63. 10.1038/nri2400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cyster JG, Schwab SR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol (2012) 30:69–94. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ueland PM, McCann A, Midttun Ø, Ulvik A. Inflammation, vitamin B6 and related pathways. Mol Aspects Med (2017) 53:10–27. 10.1016/j.mam.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kijewski A, Witsø IL, Iversen H, Rønning HT, L’Abée-Lund T, Wasteson Y, et al. Vitamin K Analogs Influence the Growth and Virulence Potential of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol (2020) 86(24):e00583-20. 10.1128/aem.00583-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McCoin CS, Knotts TA, Adams SH. Acylcarnitines–old actors auditioning for new roles in metabolic physiology. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2015) 11(10):617–25. 10.1038/nrendo.2015.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, SUB8703003.